article

begin page 4 | ↑ back to topBlake’s “The New Jerusalem Descending”: A Drawing (Butlin #92) Identified

I

The early to mid 1780s was a time of heightened awareness of apocalyptic subjects as a potential source of visual imagery. 1783 saw the exhibition of West’s Death on a Pale Horse, Barry’s Elysium, or the State of Final Retribution, and Lowe’s The Deluge.1↤ 1 Morton Paley deals with this in an as yet unpublished paper on “The Apocalyptic Sublime” delivered at the symposium held in association with the Blake exhibition at Toronto on 3 Dec. 1982. I would like to thank the Humanities Research Grants Sub-Committee of McGill University for a travel grant, and Gordon Tweedie, my research assistant, for help in the preparation of this essay. This interest may well have been triggered in part by the events and rhetoric of the American War of Independence; even as early as 1772 Joseph Priestley wrote that the developing crisis in America looked like the beginning of the end of the world: “Every thing looks like the approach of that dismal catastrophe . . . I shall be looking for the downfall of Church and State together. I am really expecting some very calamitous, but finally glorious, events.”2↤ 2 Cited by Clarke Garrett, Respectable Folly (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 1975), 130.

Blake himself began using Revelation as a basis for designs in 1784,3↤ 3 Blake’s plate of “The Vision of the Seven Golden Candlesticks” for Herries’ The Royal Universal Family Bible, dated 1782, was formerly thought to be designed by Blake, but has now been shown by Tolley and Essick to have been designed by Picart: see Robert N. Essick, William Blake, Printmaker (Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press, 1980), 48. when he exhibited a watercolor of War Unchained by an Angel, Fire, Pestilence, and Famine Following in the Royal Academy, though that design is untraced.4↤ 4 Martin Butlin, The Paintings and Drawings of William Blake (New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 1981), #187. For general discussion of this moment in Blake’s art, see the chapter “Painting and Prophecy” in David Bindman, Blake as an Artist (Oxford: Phaidon, 1977). I now propose to add to the list of early Blake versions of apocalyptic subjects a wash drawing which has not hitherto been properly identified; Martin Butlin’s proposed dating of c. 1785-90 would place it just after the designs listed, and would help bridge the gap between those early treatments and Blake’s well known series of watercolors from the 1800s.

On loan to the Fogg Art Museum at Harvard is an ink and wash drawing known by the Museum as Allegorical Female Figure, and more descriptively as #92, A Crowned Woman Amid Clouds with a Demon Starting Away by Butlin (illus. 1). Butlin records that there is a text written “illegibly on book b. 1.” and that the number “525” is written on the design, with the implication, perhaps, that the number represents an act of vandalism by an uncaring dealer, comparable to the numbers written on several Blake drawings by Joseph Hogarth.5↤ 5 See Butlin, note under #137.

A close look at the original drawing, however, suggests a different explanation. The illegible description at bottom left, though it remains unintelligible to me, is not completely illegible; one can just make out a top row of letters beginning with a capital “N” and perhaps continuing with lower case “i v i,” a second line that may begin with a capital “D” and continues with a lower case “u,” and a third line that seems to begin confidently, if unintelligibly, “L G” and continues, perhaps, with a lower case “a l i” (?). The form of this capital “G” is very similar to the form of what Butlin reads as the first “5” of “525”; on closer view, the second “5” is clearly a “G” also, and Butlin’s “2” looks more like a not completely closed “O.” The number turns into a name, and the name obviously belongs to the figure whose outline it follows. The name seems to have been written in the same dark pigment that has been used on the rest of the drawing, and the calligraphy suggests strongly that the hand that formed the letters on the open book also formed the letters of the word “Gog.” Those “G”s are very similar to the capital “G” in Blake’s drawing of The Making of Magna Charta,6↤ 6 See Butlin #62. and I shall assume henceforward that the letters were written by Blake himself.

II

The identification of the lower figure as Gog leads to a more accurate interpretation of the design, though the process is not completely straightforward. Gog appears significantly in two places in the Bible. In Ezekiel 38-39 Ezekiel is told by the word of the Lord to prophesy against Gog, “the chief prince of Meshech and Tubal,” who with his “army, . . . all of them clothed with all sorts of armour, even a great company with bucklers and shields, all of them handling swords,” will “come like a storm, . . . like a cloud to cover the land,” threatening to “carry away silver and gold, to take away cattle and goods”; this “shall be in the latter days.” But the Lord also promises that Gog and his bands will fall, and begin page 5 | ↑ back to top be given to “the ravenous birds of every sort, and to the beasts of the field to be devoured.”

The second major reference to Gog is in Revelation 20; when the thousand years during which Satan is bound come to an end, Satan “shall be loosed out of his prison, And shall go out to deceive the nations which are in the four quarters of the earth, Gog and Magog, to gather them to battle”; but finally “fire came down from God out of heaven, and devoured them.”

Blake has imaged Gog in the context provided by the account in Ezekiel. The somewhat miscellaneous hardware at the bottom of the design—one can make out a goblet, a helmet, and what look like a sword handle and a shield—derive from the descriptions in Ezekiel of Gog and his army with bucklers, shields, and swords, and the spoils of silver and gold which they will loot. Blake has pictured both spoils and weaponry as discarded in Gog’s hasty flight.

The woman descending from the clouds in Blake’s design is at first sight a puzzle, but there is a solution close at hand. The account of Gog in Ezekiel is followed by an extended revelation to the prophet of the dimensions of the temple of the Lord in chapters 40-47. The account of Gog and Magog in Revelation leads directly to the Last Judgment and the descent in chapter 21 of “the holy city, new Jerusalem, coming down from God out of heaven, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband.” That means that there is a powerful structural analogy between the last chapters of Ezekiel and the last chapters of Revelation, an analogy which Matthew Henry, in a popular Bible commentary first published in 1710, had already explicitly articulated: “These chapters [Ezekiel 40-47] are the more to be regarded, because the last two chapters of the Revelation seem to have a plain allusion to them, as Rev. 20. has to the foregoing prophecy of Gog and Magog.”7↤ 7 Matthew Henry, An Exposition of the Old and New Testament (New York; 1853), IV, 767. Henry published most of his commentary by 1710, including that on Ezekiel quoted here. A commentary on the Epistles and Revelation, using his notes, was completed after his death, and the completed commentary first published in 1811. See DNB. Blake has obviously also perceived the analogy, and has constructed his design as a kind of Aristotelian proportional metaphor,8↤ 8 Poetics 1457b, Rhetoric 1411a. identifying the prophecies of Ezekiel and John by shifting from the language of one to the language of the other within a single design. The woman in the design is Blake’s first visual representation of Jerusalem, the bridal city who is the true form and fulfillment of Ezekiel’s vision of the temple of the Lord.

Behind Blake’s readiness to fuse elements from the Old Testament prophet and John’s Revelation lies a history which is worth sketching in briefly. It was the Protestant reformers who recharged the discussion of Biblical prophecy by asserting that the Papacy was the Antichrist, and by using that to give unity to their interpretations of, primarily, Daniel and Revelation. But the Gog of Ezekiel was seen as a related figure, and there are an appreciable number of comments that constitute one historical context for Blake’s design, specifically one that supports his uniting of elements from the Old and the New Testaments. Behind this of course lies the fundamental concept of typology,9↤ 9 See Leslie Tannenbaum’s discussion in chapter 4 of Biblical Tradition in Blake’s Early Prophecies: The Great Code of Art (Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press, 1982). but this is not the place for an account of Blake’s relationship to that doctrine, and I shall restrict my quotations to comments that bear fairly directly on the design under discussion.

Joseph Mede, in his widely read comments on Revelation, described Gog and Magog as the “counter-type” of the Gog of Ezekiel, which “should after the same manner attempt against the Beloved City then, which the Scythian Gog and Magog (I mean the Turk) [i.e. the Gog of Ezekiel] doth against the Chuch of the Gentiles now.”10↤ 10 The quotation comes from The Third Book of the Works of the Pious and Profoundly-Learned Joseph Mede, B.D. (London, 1664), 751. David Pareus, in another widely read commentary, also sees analogy or typology rather than identity as the relation between the two prophecies: “The sense is thus: Like as of old Gog and Magog invaded the Holy Land with very great Armies. . . . So Satan being loosed at the end of the thousand fatall years, shall raise up against the Church a new Gog and Magog, that is, most cruell adversaries. . . .”11↤ 11 David Pareus, trans. Elias Arnold, A Commentary Upon the Divine Revelation of the Apostle and Evangelist John (Amsterdam, 1644), 536. The two commentators differ in their historical identifications—Mede sees the Gog of Ezekiel as referring to the Turkish enemy of the Church in Mede’s own time, while Pareus sees him as referring to an episode in the past—but both see the relationship between the two prophecies as analogical and typological.

From 1710 comes Matthew Henry’s statement of the double analogy between Gog, Magog, and the temple in Ezekiel, and Gog, Magog, and the new Jerusalem in Revelation, a statement I have already cited. Henry’s commentary went through a series of editions well into the nineteenth century.

Somewhat later Isaac Newton wrote an essay on Daniel and Revelation as prophecies. While accepting and refining what were rapidly becoming standard historical identifications of prophetic references, he also formulated an overall view of prophecy as a particular form of “figurative language . . . , taken from the analogy between the world natural, and an empire or kingdom considered as a world politic.” This language has a distinctly Blakean ring to it: “the heavens, and the things therein, signify thrones and dignities . . . , the earth, with the things thereon, the inferior people; and the lowest parts of the earth, called Hades or Hell, the lowest or most miserable part of them.”12↤ 12 Isaac Newton, Observations upon the Prophecies of Daniel and the Apocalypse of St. John (London, 1733), 16. Newton sees this language shared by Daniel and Revelation as fusing them together into “one complete Prophecy.”13↤ 13 Newton, 254. Prophecy, in other words, not only points to specific historical events, but also constitutes an always available poetic language.

At about the same time William Lowth wrote a major commentary upon the prophets, including Ezekiel, which was influential into the early nineteenth century. Lowth identifies the prophecy of Israel’s final victory over Gog and Magog in Ezekiel 38 and 39 as relating begin page 6 | ↑ back to top

When Lowth discusses the chapters in Ezekiel that describe the Temple, he is much more explicit in articulating the relationship with Revelation: “The Temple, and the temple worship, was a proper figure of Christ’s Church, and of the spiritual worship to be instituted by him.” Lowth recognizes that “The New Testament copies the style of the Old,” and exemplifies this by explaining that “St. John in the Revelation, not only describes the heavenly sanctuary by representations taken from the Jewish Temple, Rev. XI.19. XIV.17.XV.5,8. but likewise transcribes several of Ezekiel’s expressions, Rev. IV. 2,3,6. XI. 12. XXI. 12, & XXII. 1,2. and borrows his allusions from the state of the Temple as it was built by Solomon, not as it stood in our Saviour’s time; as if the former had a more immediate reference to the times of the Gospel.”15↤ 15 Lowth, 339-40. Lowth also cites a more literal-minded unifier of the two versions of the temple: “the learned Mr. Potter, in his Book of the Number 666, hath, with great acuteness, reconciled the 1200 furlongs, the measure of the New Jerusalem in the Revelation, with the measures of Ezekiel here [48:20], by interpreting them of solid measures, and by extracting the root of each of them” (Lowth, 366). Lowth’s references, particularly the reference to Revelation 21:12, make it quite clear that he sees Ezekiel’s temple as a true figure or type of the new Jerusalem.

This highly selective collection of commentary should be sufficient to show that there is a substantial body of interpretation in the background to support the intellectual structure of Blake’s design. To combine elements from Ezekiel with a basic structure taken from Revelation is to work within the mainstream of Protestant commentary on biblical prophecy. But one can still ask whether Blake, in combining elements from the Old and New Testaments, is to be understood as illustrating the text of Revelation (using additional details from Ezekiel), or as formulating a new, compound statement based on extant prophecies, but extending and changing their language—in other words, is he really creating a new but implicit text, founded on the prophets but constituting a new virtual text of his own invention?16↤ 16 I have discussed this question in “Reading Blake’s Designs: Pity and Hecate,” BRH, 84 (1981), 337-65.

Blake’s contemporary and nearly contemporary writing suggests that this is indeed how he understood the relationship between prophecy and creation. In All Religions are One from 1788, he treats “the Jewish & Christian Testaments” as being equally “An original derivation from the Poetic Genius,” which is “every where call’d the Spirit of Prophecy.”17↤ 17 David V. Erdman, ed., The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake (Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 1982), 1. Further references will be parenthetical. And in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, Ezekiel is equally clear that prophecy derives from the Poetic Genius, and that the prophet’s true function is not to predict, but to raise “other men into a perception of the infinite” (E 39). I think that we can be confident that Blake held something like these views at the time he created the drawing, and that he felt free to combine statements from both “The Jewish & Christian Testaments” into one poetic vision of the victory of freedom and truth over tyranny and blindness.

III

The relationship between Blake’s design and earlier versions of the subject can be dealt with fairly briefly, since there were relatively few. Louis Réau has pointed out that apocalyptic subjects become popular only at times of major epidemics, religious ferment, and social and political upheaval.18↤ 18 Louis Réau, Iconographie de l’art chretien, II, ii (Paris: Presses universitaires de France), 724. Frederik van der Meer, L’Apocalypse dans L’art (Paris: Chene, 1978), 48, states that Dürer’s set of woodcuts dominated the field until well into the eighteenth century. The reformation brought forth many versions, but such subjects only became really popular again in the 1780s, to which moment Blake’s design belongs.

By far the most influential printed series of illustrations of Revelation was Dürer’s set of 1498, versions of which appeared in Luther’s Bible and many subsequent editions. In one of these woodcuts (illus. 2) Dürer shows John before the city of the new Jerusalem in the upper part of the design, and Michael about to stuff Satan back under the ground in the lower part. This is not identical with the subject of Blake’s design, but there is overlap, and both share analogous two-part structures.

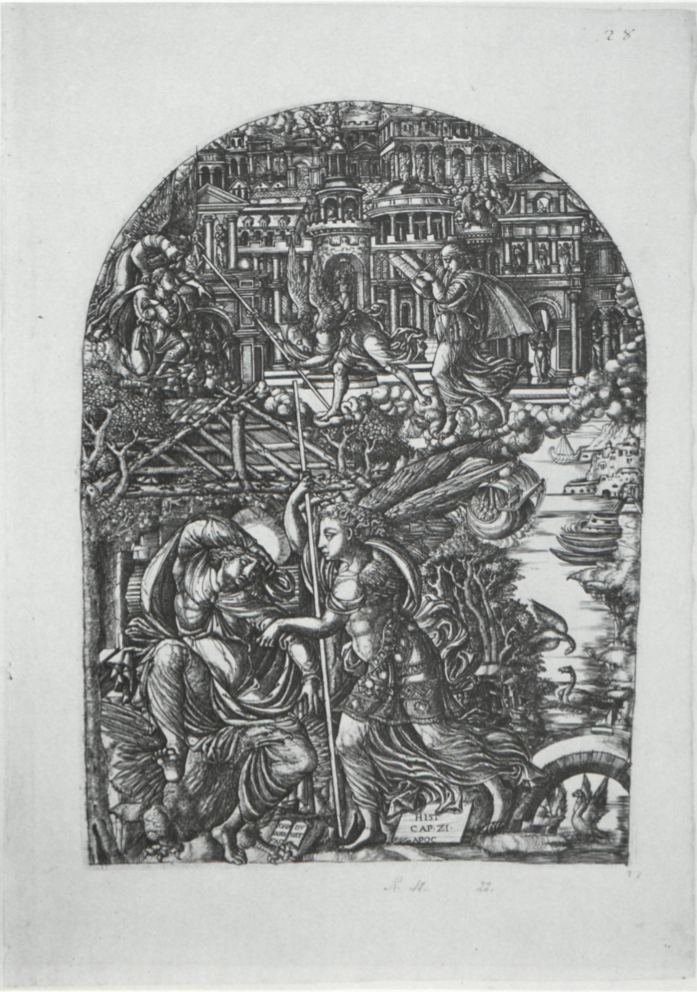

In 1561 Jean Duvet published a very interesting series of twenty-three engravings in a volume titled L’Apocalypse figurée, a title which reflects Dürer’s Apocalypsis cum figuris.19↤ 19 On Duvet, a very interesting and original engraver, see Colin Eisler, The Master of the Unicorn: The Life and Work of Jean Duvet (New York: Abaris, 1977). The engravings briefly discussed here are nos. 59 and 60 in his catalogue. Two of the series come close to the subject of Blake’s design. The first illustrates Revelation 20, and shows a castle at the top with, below, an angel chaining Satan and, below that, another angel driving Satan into “the bottomless pit.” The other (illus. 3) shows, below, an angel waking John to show him the new Jerusalem, which fills the upper part of the design. An angel with a measuring reed is at work before the city, a detail derived from 21:15, which in turn derives from Ezekiel 40:3.

One further version is worth noticing. F. van der Meer illustrates a sixteenth century tapestry showing the new Jerusalem above a battlefield on which the armies of Gog and Magog are being destroyed, while Michael leads off a many-headed tentacled Satan.20↤ 20 Frederic van der Meer, 315-26 and illus. 217. With its multitude of figures, this has very little relationship to Blake’s design, but it does show Gog and Magog, and that is very rare.

If we compare Blake’s design with these earlier versions, admitting that the subjects are not identical, two immediately striking differences present themselves. One is Blake’s characteristic tendency, visible even this early in his career, to visualize an image in the form of the vehicle rather than the tenor—Jerusalem is pictured as a woman.21↤ 21 See Heppner, 343-44, 353. The other is the drive towards simplification, another lifelong characteristic of his work. Here the situation has been pared down to only two figures and a few items of hardware.

This simplification changes the dynamics of the situation as narrated in Revelation. There, the agencies of the action in chapter 20 are unnamed images of spiritual begin page 10 | ↑ back to top power: an angel binds up Satan in vv. 1-3, and fire comes down from God to devour Gog and Magog in v. 9. These victories are separate from, and preparatory to, the descent of Jerusalem in chapter 21. Dürer respects this division by showing John recording the vision in the upper part of the design, while Michael binds and disposes of Satan in the lower. The two actions appear simultaneous but separate, with no visual dynamic or logic to connect them other than their appearance within a single landscape.

In Blake’s version, Jerusalem descends in a flood of light to open up the dark clouds that move off to the sides. She does not look at Gog, but the line of his body follows the angled line of parting clouds (as does his name), and those same clouds darken his body. The dynamics of the design suggest that Jerusalem herself has vanquished and scattered Gog, pushing him out of the frame—his darkness flees her radiance. The structure of the design itself is evidence that Blake is not illustrating Revelation and Ezekiel directly, but is rather illustrating—or creating—a prophetic text of his own, based on, but not limited by, the language of those earlier prophets.

One result is that the design has communicated part of its essential meaning even without a recognition of the texts that lie behind it. Butlin’s title, developed from Rossetti, identifies a “Demon Starting Away” and “A Crowned Woman Amid Clouds”; that simple act of description already points to the basic structure, the retreat of something ugly and evil before the descent of something fine and beautiful. It may indeed, up to a point, be the case that, as Blake claimed, “True Painting” is “addressed to the Imagination which is Spiritual Sensation & but mediately to the Understanding or Reason” (letter 23 August 1799, E 703).

But it is also true that Blake—so I have argued—inserted the name Gog in order to give that figure, and by implication the other figure also, a more specific and culturally based identity. The identification invites us to use our knowledge to make specific interpretative connections; as Blake also wrote, “to Labour in Knowledge is to Build up Jerusalem: and to despise Knowledge, is to Despise Jerusalem & her Builders” (J 77, E 232).

IV

Most commentators on the prophetic books of the Bible had been very concerned to make specific historical identifications, and the fact that Blake reshaped the Revelation account increases the probability that he too saw his design as having a specific relationship to contemporary history, of the general kind suggested by the quotations from Priestley given above. Two possible contemporary applications suggest themselves.

The first, intriguing but highly unlikely, would depend in part on the fact that Blake has made Jerusalem herself appear to be the agent as well as the result of the defeat of Gog, and in part on the identification that most commentators had made between Gog and Magog and the Scythians and/or Turks. Russia commenced a major offensive to win territory from the Ottoman empire in 1787, in which year Catherine, on a ceremonial visit to the Crimea, passed under an arch inscribed “The way to Constantinople” as a symbol of her intentions. This sparked two splendid caricatures,22↤ 22 See Catalogue of Prints and Drawings in the British Museum, Division 1 Political and Personal Satires, vols. 5-11 by Mary Dorothy George (London: British Museum, 1870-1954), vol. 6, nos. 7180 and 7843. The creator of the first is unknown; that of the second is probably H. Wigstead or W. Holland. but Catherine’s sexual reputation makes it virtually impossible to associate her with the figure of the new Jerusalem in Blake’s drawing, and another historical target for Blake’s design is much more likely.

Commentators on the prophecies had been widely impressed by the text of Daniel 7:19-28 that identified the ten horns of the fourth beast as “ten kings that shall arise,” and King James himself had identified these, and the horns of Revelation 17, as the kings of Europe.23↤ 23 LeRoy E. Froom, The Prophetic Faith of Our Fathers, 4 vols. (Washington, D.C.: Review and Herald, 1948), II, 541, and the tables of identification, 528-31. Chapter 32 is titled “Predictions of French Revolution and Papal Overthrow,” and provides further relevant context for Blake’s drawing. This identification made it easy to see these horned beasts as images of one aspect of Antichrist, and thus as associated with Gog and Magog in meaning. The power of the European kings had been badly shaken by the creation of the American Republic, and there were many prophetic statements that pointed forward to the French Revolution and the downfall of European monarchy. Even as early as 1772 Priestley had made the general prediction of the “downfall of Church and State” cited above; by 1794, he was specifically identifying the crowned heads of Europe with the horns of the beast in Revelation, and declaring that “the execution of the king of France is the falling off of the first of these horns; and . . . the nine monarchies of Europe will fall one after another in the same way.”24↤ 24 Garrett, 133.

Blake’s drawing can be seen as dressing such a political hope in prophetic and apocalyptic imagery. The political and military tyranny which had always been associated with Gog makes him a more suitable choice for the defeated villain than the Satan who was so common in analogous earlier designs. The vision of Jerusalem as the image of the new society of freedom that replaces the old tyranny suggests a faith in the inevitability of transformation. The drawing can then be related to such designs as that of The King of Babylon in Hell (Butlin #145), dated c. 1780-85, which illustrates a text from Isaiah, and perhaps the lost War Unchained by an Angel, Fire, Pestilence, and Famine Following, which Blake exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1784.25↤ 25 Butlin #187, and the presumed sketch, #186. They would all represent versions of “the historical fact [given] in its poetical vigour” (DC, E 543), visions of contemporary events or trends interpreted through the poetic language created by “the Spirit of Prophecy.”

begin page 11 | ↑ back to topV

It remains to say a word about the later careers of the two symbolic figures that Blake here uses for the first time. Gog, usually with his sidekick Magog, has a modest future in Blake’s work. The two together appear in an odd passage in A Vision of The Last Judgment (E 558), where they are described as having been compelled to subdue Satan their master, with Ezekiel 38:8 given as a reference (an error for 38:7—“and be thou a guard unto them”?). I shall not attempt to explicate this passage here, but it does show Blake again treating the prophecy in Ezekiel as an extension of Revelation. Later still, Gog’s name is attached to Hyle as the latter attempts to draw Jerusalem’s Sons toward Babylon in Jerusalem 74:28-31, a passage which once more defines Gog and Jerusalem as polarized terms. Finally, Gog and Magog appear together as “the Triple Headed Gog-Magog Giant” that “Taxed the Nations into Desolation” at the end of Jerusalem (98:52-53). Here Gog and Magog still function as a symbol of the totality of political and economic aggression that gathers to a head before the final liberation, no doubt with the implication of a more specific aim at Pitt and subsequent war administrators.

There is no need to comment at length on the future centrality of the figure of Jerusalem to Blake’s work. This drawing would seem to be her first appearance there, and from the beginning she is in her human rather than her civic form, “a City yet a Woman” (FZ 122:18, E391). Her bridal attire is simple, a white gown and small crown. The revelation of the glory of her naked freedom will come later. But I propose that her first appearance here be marked by renaming the drawing “The new Jerusalem descending.”