article

begin page 116 | ↑ back to topVala’s Garden in Night the Ninth: Paradise Regained or Woman Bound?

The “pastoral” dream in the last pages of William Blake’s Four Zoas lies at the center of Night the Ninth, whether you count lines or Blake’s own pages.1↤ 1 “You answer not then am I set your mistress in this garden” is line 429 in a Night containing 855 lines; the manuscript at Night Nine’s center (ms. page 128) contains Vala’s “new song,” her slumber with the Ram, etc. See The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake, ed. David V. Erdman (Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 1982), pp. 396-97. All further references to this work appear in the text in the following format: (Four Zoas page: line; Erdman page). The fact that this apocalyptic pastorale occurs at the Night’s exact middle, dividing one half of Blake’s upheaval of the universe from its tortured other half, makes it seem very much the hurricane’s calm eye, and so most scholars tend to take it. Blake’s reapers, resting “upon the Couches of Beulah,” are “entertaind” (131:558; E 400) by his vision of Vala’s Garden, a kind of Beucolic dream. (Note the useful neologism: “Beulah” + “bucolic” = “Beucolic.”) Yet the “dews of death” in this dream, its “impressions of Despair” (126:389, 377; E 395), convey a subtle uneasiness, a disturbance especially noticeable when the visionary imagery condenses around Blake’s female figures. For the Emanations undergo curious sufferings. Male Zoas seem to encircle them with doubt, fear, and anxiety—the very atmosphere they move in disconcerts our expectations of pastoral. A reader who pays close attention to Blake’s females will find it hard to accept the traditional interpretation, put forth by Northrop Frye, Harold Bloom, and others, that this Ninth Night vision is a joyful celebration of innocence amid the throes of final universal regeneration.2↤ 2 This article began as a seminar paper for Professor Donald Ault of Vanderbilt University and reflects his general approach to Blake. See Northrop Frye, “The Nightmare with Her Ninefold,” in Fearful Symmetry: A Study of William Blake (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton Univ. Press, 1947), pp. 305-08; and Harold Bloom, Blake’s Apocalypse: A Study in Poetic Argument (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell Univ. Press, 1963), pp. 266-72. By questioning the gender conflicts in Vala’s Garden, this reader will also question critics’ attempts to inflict “closure” on the Four Zoas as a whole. How can there be universal regeneration when male and female remain at war?

This paper will argue (against a number of scholars) that through its female figures the dream subverts rather than celebrates pastoral as usually defined, and that this subversion compromises the rest of Blake’s Ninth Night. With a bizarre repetitive effect, near-identical episodes of sexual conflict disperse throughout the poem. Blake’s females seem doomed to a cyclical, not a linear narrative, and in reenacting failures, they set a pattern that detracts from the finality of apparently apocalyptic events in Night the Ninth. For too long we have viewed the poem as somehow forward-directed in time: the recurring events of Blake’s recycling poetry overthrow that tendency and along with it the tendency to view male Zoas and their female Emanations as finally reconciled at the end.

It is not at all easy to see exactly how Blake’s Beucolic vision fits in with the rest of Night the Ninth. The dream begins with Luvah and Vala’s descent to the “Gates of Dark Urthona,” a descent which: “those upon the Couches viewd . . . in the dreams of Beulah / As they reposed from the terrible wide universal harvest” (126:375, 383-84; E 395). It fades away with a tense union between Tharmas and Enion as “shadows . . . in Valas world”; “the sleepers who rested from their harvest work” still watching “entertaind upon the Couches of Beulah” (131:556-58; E 400). The narrative dream sequence in between these lines seems at first entirely at odds with the rest of Blake’s cataclysmic Ninth Night: pervading imagery comes from traditional pastoral, and a rich lyrical language echoes Latin myth, the lore of paradise, the Song of Songs. Critics intent on bending Night the Ninth into coherent shape describe this Beulah dream as an interruptive “pastoral interlude,” an innocent dalliance or “masque”3↤ 3 Brian Wilkie and Mary Lynn Johnson, Blake’s Four Zoas: The Design of a Dream (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Univ. Press, 1978), p. 223. dished up by Blake as welcome relief from the terrifying earthquake tumult of his final Night. Yet even when his language recalls pastoral and hymn, even as he soothes us, like the harvesters, into a reverie of fantastic loveliness, Blake lulls us into a false sense of security.

The poet’s description of Vala’s Garden strikes at its outset a jarring note unheard in conventional pastoral, however melancholy: “in the shadows of Valas garden / . . . the impressions of Despair & Hope for ever vegetate” (126:376-77; E 395). Such lines remind us, before we succumb to the roseate vision of Vala frolicking with her docile flock, that only fourteen lines before their descent into this garden, Luvah and Vala were “the flaming Demon & Demoness of Smoke.” The transformation, as so often in Blake, has been from one extreme to another, but one wonders in what sense the pair have changed. For Luvah and Vala actually preserve something of their smoky, demonic natures in a subterranean world quite foreign to the setting of pastoral, normally a hill in the open air. It seems odd that Blake should bury his fields—his “garden”—beneath the ground, and beyond the dark hellish gates of Urthona. As for the “earthly paradise” generic pastoral regains, do we begin page 117 | ↑ back to top get it in uncorrupted form? Alicia Ostriker can call this “pastoral episode” an “idyllic evocation of a new Golden Age” only by overlooking Enion’s fear of Tharmas and Vala’s subservient relationship to Luvah, her distant “Lord” (129:501; E 398). The half-submerged anxiety of male/female encounters flattens whatever sounds like Golden Age harmony.4↤ 4 Frye puts Urthona underground; the word “descended” (126:375; E 395) helps confirm this placement. See Frye, p. 278; and Alicia Ostriker, “Desire Gratified and Ungratified: William Blake and Sexuality,” Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, 16 (1982-83), 160.

Like Ostriker, Wilkie and Johnson note a “redeemed view of physical nature,”5↤ 5 Wilkie and Johnson, p. 225. but they fail to recognize that this “redeemed view” seems more the result of a claustrophobic denial of the senses then a true renewal: “They [Luvah and Vala] heard not saw not felt not all the terrible confusion / For in their orbed senses within closd up they wanderd at will” (126:381-82; E 395; emphasis added). Here, at the very beginning of the Beucolic vision, Blake gives us a scenario of withdrawal and deprivation. Moreover, the relationship between Luvah and Vala also changes radically, and one can hardly say for the better. Whereas before they had walked together, Luvah now rises “over Valas head” (126:385; E 395) and starts playing the role of a Godlover. His elevation makes him invisible to her (again denying the senses), but increases his control, for his voice now has the power of deity. In this “land of doubts & shadows sweet delusions unformd hopes” (126:379; E 395), the apotheosis of Vala’s mate means that she loses him. The next question is, what place has deprivation, what mean these forms of despair in a place so sheltered and ideal?

Overlooking such pitfalls in the text, Bloom contends that “Blake’s imagery of Innocence” in this “Garden of Innocence” is “expressed with a new confidence, a firmness based upon definite organization.” Whereas “Blake’s pastoral vision” was a “deliberate failure . . . in the Songs of Innocence,” here it is a “triumph.” Granted, those ignes fatui of Innocence that so caught Bloom’s eye do flash fitfully throughout the pastoral sequence. Yet since one enters this garden through Urthona’s dark gates, with “orbed senses . . . closd up,” as in death, the garden imagery could just as well be Elysian as Edenic. In

another poem, Jerusalem, Blake associates “The Veil of Vala” with the creation of “the beautiful Mundane Shell, / The Habitation of the Spectres of the Dead.” Perhaps in The Four Zoas, too, Vala’s Garden, veiled in darkness, belongs more to the shadowy dead than to living lovers. Elysian Fields are beautiful, but for all that in Hades. When at the end of the sequence Blake again tells us that “Luvah & Vala were closd up in their world of shadowy forms” (131:559; E 400), we might follow Kathleen Raine’s interpretation and think those “forms” Platonic. Yet they could just as well be the “sweet delusions” of a deprived, spectral underworld, where even the deified male shares his subjected mate’s imprisonment.6↤ 6 Bloom, Blake’s Apocalypse, pp. 274-75; Blake, Jerusalem, pl. 59, lines 5-8, E 208; Kathleen Raine, “Blake’s Debt to Antiquity,” Sewanee Review, 71 (summer 1963), 373.It needs pointing out that while Vala’s Garden may or may not be Elysian, it is remarkably feminine. In fact, because this dream incubates in the female domain of Beulah, we should hesitate before we label its “sweet delusions” wholly harmless. Beulah is, after all, a quintessentially womanish realm: “There is from Great Eternity a mild & pleasant rest / Namd Beulah a Soft Moony Universe feminine lovely” (5:93-94; E 303). And such an origin implies negative opposition to the poem’s predominantly masculine universe. Both Susan Fox and Anne Mellor have argued that, for whatever reason, Blake associates a kind of threatening “weakness” with the female principle: whenever his masculine and feminine figures come together, the female will either submit or menace. Whether Blake opposes male/female domains to make social comment or “pure” symbolic organization (or both) is another matter, but the very landscape of Vala’s Garden, as a creation of womanish Beulah, inevitably suggests a sexuality issue. And since in Blake the feminine principle must either give battle or bow to its parent masculine principle, it need not surprise us that this apparently “idyllic” Garden makes an occult forum for male/female conflict. The reader who looks for it will find that both pairs, Luvah and Vala, Tharmas and Enion, spark (on contact) with a dangerous electricity that is not at all as “playful” as Wilkie and Johnson would have us believe.7↤ 7 Susan Fox, “The Female as Metaphor in William Blake’s Poetry,” Critical Inquiry, 3 (1977), 516; Anne K. Mellor, “Blake’s Portrayal of Women,” Blake / An Illustrated Quarterly, 16 (1982-83), 148; and Wilkie and Johnson, p. 227.

Bloom finds the nature of this Beucolic sexual drama more complex than playful, but he insists on its redeemed “innocence”: “Luvah and Vala, Tharmas and Enion, are reborn into Beulah, to the accompaniment of Blake’s most rapturous hymns of innocence; nervous, intense and vivid . . . effective projections of paradise.” Nervous and intense these “projections” certainly are, but in what way are they paradisal? In my reading, the paradisal quality of this dream arises from the traditional association with Eden that almost every remarkably beautiful garden in Western literature has, and fragments of the traditional language to describe such a garden do scatter through Blake’s lines. It is the subliminal sexuality of garden myths, however, here more persistent than the Edenic images, that gives this “rapturous begin page 118 | ↑ back to top hymn” its discordant notes. “Shadows” and “doubts” haunt the landscape, and sensitivity to them allows room for readings more compatible with what Bloom recognizes as “nervous.” Ostriker, for instance, opens up a number of possibilities when she anatomizes Blake’s Garden as “the body of a woman” desired yet forbidding, shadowed and mysterious.8↤ 8 Harold Bloom, “States of Being: The Four Zoas,” in Blake: A Collection of Critical Essays, ed. Northrop Frye (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1966), p. 118; and Ostriker, p. 156.

Such symbolism illuminates Blake’s use of erotic language from the Song of Solomon, a poem which, like Vala’s Garden, links feminine enclosure with male ownership: “A garden inclosed is my sister, my spouse . . . Let my beloved come into his garden” (SS 4:12, 16).9↤ 9 Biblical quotations are from the King James version. Like Vala, the woman of the Song searches for her lost lover: “I sought him, but I could not find him” (SS 5:6). Yet, while Blake’s lines echo the Old Testament love poem out of what sounds like sheer elation (“dost thou hide in clefts of the rock” [129:101; E 398]; “O my dove, that art in the clefts of the rock” [SS 2:14]), the Beucolic drama invokes more than familiar biblical language. Vala and her Garden are an icon of the kept female—both associated with a garden and enclosed by it. The closer one looks, the more complex this garden interlude becomes.

First of all, the whole sequence begins with an outright command to regress, delivered by none other than Blake’s “Immortal”: “Luvah & Vala . . . / You shall forget your former state return . . . Into your place the place of seed . . .” (126:363-65; E 395). This “place of seed,” presumably the visionary Garden, has a womblike character; partly because the dream itself gestates in the feminine realm of Beulah, partly because Blake uses womb images. When Luvah and Vala “enterd the Gates of Dark Urthona” (126:375; E 395), for example, they actually seem to have passed into that ever-desirable place of origin where fetal “unformd hopes” lie in a “shadows” state of embryonic Becoming. The two “closed up” images noted earlier (“their orbed senses within closd up” [126:382; E 395]; “closd up in their world of shadowy forms” [131:559; E 400]) could serve this reading as suggestions of the hortus conclusus (“closed garden”), in medieval works symbolic of the Virgin Mary’s womb. At its very beginning, then, the Beucolic dream returns to that prenatal oblivion in which the unborn “heard not saw not felt not all the terrible confusion” (126:381; E 395); it plays out, in other words, something like primal wish-fulfillment.

Even when the dream emerges from this womblike regressive stage and becomes instead a forum for erotic exchange between Luvah and Vala, Tharmas and Enion, the wish-fulfillment continues. Only now Blake works it out with a marked difference. Luvah and Vala, male and female, shared their return to the womb; in the later fantasy sequences, male desire alone holds sway.

For the Zoa Tharmas, family romance in Vala’s Garden seems virtually ideal. Luvah, potentially a father-figure, remains “Invisible” (126:385; E 395) throughout the dream and thus never competes for the maternal Vala’s attention. (In this respect, Vala’s Garden scenes recall the Songs of Innocence, where that masculine “authoritarian figure,” as Donald Dike calls him, also remains largely absent, although in the more troubled Songs of Experience he is conspicuously and significantly present.10↤ 10 Donald A. Dike, “The Difficult Innocence: Blake’s Songs and Pastoral,” ELH, 28 (Dec. 1961), 354. Tharmas’s Oedipal attachment to his sensual, cosseting Vala—she is no longer the dangerous femme fatale of other Nights—never becomes a problem; he can enjoy both her maternal attention and the pursuit of Enion, his reluctant but pliant object of desire. “Open” as Tharmas’s infant sexuality may be, however, the Beulah vision itself is hardly frank—or benevolent. Even Tharmas sheds copious tears, tears that threaten to flood this Garden of “infant doubts” and “sorrow” (131:552-54; E 399-400). It is the strangely disturbed relationship between Enion and her “child” pursuer, however, that most clearly defies justification.

Herbert Marcuse observes that “phantasy,” by indulging the pleasure principle, tends to oppose “normal sexuality” as “organized and controlled by the reality principle.” Certainly, parts of this Beulah dream qualify as pleasurable phantasy—and its sexual drama indeed unfolds on the dark side of “normality.” Its most striking characteristic is a teasing inconclusiveness: the two couples, Luvah and Vala, Tharmas and Enion, go through the first phases of seduction, but their troubled courting leaves phantasy lingering, so to speak, on the brink of fulfillment. George Harper writes that Blake achieves ultimate “regeneration” of our “whole fallen world” through Night the Ninth’s “great pastoral vision . . . begin[ning] with Luvah’s symbolic call to his stricken mate for a return to ‘their ancient golden age’ . . . when man and nature were not separate.” The odd fact that Luvah and Vala, that is man and woman, remain separated throughout the vision does not trouble Harper. Yet it seems crucial; Luvah’s invisibility, the fact that he even stops talking to Vala after the dream’s first forty-seven lines, makes those readings that insist on perfect union (of any sort) highly dubious.11↤ 11 Herbert Marcuse, Eros and Civilization: A Philosophical Inquiry into Freud (Boston: Beacon Press, 1966), p. 146; and George Mills Harper, “Apocalyptic Vision and Pastoral Dream in Blake’s Four Zoas,” South Atlantic Quarterly, 64 (winter 1965), 121.

Attempts to redeem the Beulah vision have taken ingenious turns, particularly by way of digging up literary sources: if not biblical, then classical. Granted, Blake’s dream does look notably similar to Apuleius’s version of the Cupid and Psyche myth, and Vala’s experience does resemble Psyche’s in a number of interesting ways.12↤ 12 See Book V, The Golden Ass of Lucius Apuleius, trans. William Adlington, ed. F.J. Harvey Darton (New York: Hogarth Press, n.d.), pp. 161-62. But what those who see Luvah and Vala as Blake’s Cupid and Psyche fail to recognize is that the sexual union of god and woman, not to mention their marriage in heaven, never occurs in Blake’s own Beucolic dream. Instead, Luvah’s god-like power over Vala remains a barrier: their desire for each other deflects, and the working-out of that repression happens in an eccentric, even perverse way.

begin page 119 | ↑ back to topIf the first hundred lines of the dream recall classical myth, they do not prepare us for what happens later. Only the beginning conforms: Luvah, as Kathleen Raine tells us, plays the part of Apuleius’s Cupid, invisibly courting his Psyche/Vala and building her a splendid house. There is even a hint that Blake’s “Lord of Vala” follows the medieval interpretation of Cupid and Psyche as Christ and Soul, for Vala thinks of him as her creator and seeks him with great longing. (The same kind of interpretation saw Christ as Lover in the Song of Solomon and his beloved as Soul or the Church.) Acknowledging all this, we may now ask the crucial question: what does Blake do with such associations? Had he ended the dream on his manuscript page 128, Raine’s analysis of sources might have had the last word. But here we lose sight of the Cupid and Psyche myth: Vala does not find Luvah. She even stops looking for him. Leading her flock in song, stroking their backs while they lick her feet, she eventually lies down with “a curld Ram who stretchd himself in sleep beside his mistress.” Sleeping, she dreams of her “bright house”: when she awakes she sees that house materialized and calls it her “bodily house” (128:456, 466, 470; E 397). After exploring this dwelling, she bathes in a river, and not long after her immersion, two children, a boy and a girl, appear on the scene. This bizarre series of events seems a distorted enactment of what might naturally have happened between Luvah and Vala after their lyrical courtship, for when Tharmas and Enion appear, one suspects that Vala has in some dream-like way given birth to them, even that her sleeping with the Ram (a substitute for Luvah) had something to do with finding these children for her “bodily house.” If this part of Night the Ninth is indeed Blake’s prophecy of regeneration, his vision of perfection and freedom, why does it follow the usual dream pattern of repressed wish-fulfillment? Is repression the inevitable outcome of Luvah’s exaltation over Vala? And why does the ensuing scene between Tharmas and Enion remain so disturbingly uneasy?13↤ 13 Raine, “Blake’s ‘Cupid and Psyche,’ ” The Listener, 58 (1957), 832-35. See also Jean H. Hagstrum, “Eros and Psyche: Some Versions of Romantic Love and Delicacy,” Critical Inquiry, 3 (1977), 523.

Critics have tried to ameliorate the Tharmas/Enion seduction scene. Michael Ackland writes that the two children represent “instinctual passions [which] have to relearn their innocence under the guidance of a morally regenerated Vala.” Wilkie and Johnson go even further: “The terrible quarrel between [Tharmas] and Enion which had opened Night I is now playfully repeated in the courtship spats between those children, easily settled by the now-motherly Vala.” Blake’s purpose as they see it is: “To show the psychic redemption of passion as innocence . . . passion has now become . . . identified with [the] instinctual innocence [of children].” The problem with such readings of the Beucolic sequence is that they ignore Vala’s sinister or “shadowy” quality, Tharmas’s oddly excessive lament, and Enion’s stubborn resistance to him. Vala does act in a “motherly” way when she embraces the children, puts them to bed, etc. Evidence for her “moral regeneration,” however, is missing, especially when one considers how she helps Tharmas gain what sounds very much like control over Enion. The dream’s treatment of “instinctual” infantile sexuality exemplifies what Morris Dickstein calls Blake’s “reading of Freud,” but what happens between Tharmas and Enion no more qualifies as a “courtship spat” than the cataclysmic rape in Night I qualifies as a “quarrel.” In fact, traces of that rape darken its childhood version in Vala’s Garden. For however “healthy” Tharmas may be in expressing his infantile passion (and I am not at all sure he makes a convincing child), Enion does not give a “healthy” response. As in Night the First, she plays the victim, always turning away from Tharmas and avoiding his eyes. Even at the dream’s end uncomfortably prone to “infant doubts,” she makes her own psychic correspondence to the Garden’s “shadows” and “despair.” Why, we may well ask, must she remain so painfully mute—throughout the entire dream?14↤ 14 Michael Ackland, “The Embattled Sexes: Blake’s Debt to Wollstonecraft in The Four Zoas,” Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, 16 (1982-83), 180; Wilkie and Johnson, p. 227; and Morris Dickstein, “The Price of Experience: Blake’s Reading of Freud,” in The Literary Freud: Mechanisms of Defense and the Poetic Will, ed. Joseph H. Smith, M.D. (New Haven, Conn.: Yale Univ. Press, 1980), pp. 67, 100.

Together, Vala and Tharmas manage to corner Tharmas’s object of desire, the prize of his anguished obsession. Notions of disturbance and menace do not arise in the readings by Ackland, Wilkie, and Johnson, but Tharmas’s “childish” complaint should give us pause:

O Vala I am sick & all this garden of PleasureAlong with its surprising maturity, this boy-lover’s complaint with all its watery images (“swims,” “water lilly,” “drink,” “weep”) sounds very much like his other lament voiced earlier “beside the wavy sea”:

Swims like a dream before my eyes but the sweet smelling fruit

Revives me to new deaths I fade even like a water lilly

In the suns heat till in the night on the couch of Enion

I drink new life & feel the breath of sleeping Enion

But in the morning she arises to avoid my Eyes

Then my loins fade & in the house I sit me down & weep.

(131:538-44; E 399)

O Enion my weary head is in the bed of deathDuring the “O Enion” plaint, Tharmas is a bearded adult; for the “O Vala” song, he has become a child again, a “little Boy” to whom Vala exclaims: “How are begin page 120 | ↑ back to top ye thus renewd” (130:510-11; E 398). Yet what real change has occurred in what he says? What kind of regeneration can the critic read into repetition?

For Weeds of death have wrapd around my limbs in the hoary deeps

I sit in the place of shells & mourn & thou art closd in clouds

When will the time of Clouds be past & the dismal night of Tharmas

Arise O Enion Arise & smile upon my head . . .

When wilt thou smile on Tharmas O thou bringer of golden day.

(129:487-91, 493; E 398)

Tharmas and Enion, pursuer and pursued both, remain ambivalent figures. Perhaps Vala’s rapt exclamation on Tharmas’s “renewal” does not, after all, mean inner renewal. And as for Vala herself, the role she takes on as mediator between the two children is solely played out for Tharmas’s sake. She saves her “motherly” chiding for Enion, and sternly commands the silenced little girl, however, “reluctant,” to follow Tharmas into “the shadows of her garden” (131:552, 546; E 399). Whatever these “shadows” are, they seem to cause Enion her “infant doubts,” and thus when one reads “In infant sorrow & joy alternate Enion & Tharmas played,” one wonders if that “sorrow” belongs solely to a subject Enion, the “joy” to a triumphant Tharmas. (Blake suggests this matching by switching the usual order of their names.) Dickstein calls “a conception of infant sexuality . . . both source and metaphor for the undistorted erotic life of the adult.”15↤ 15 Dickstein, p. 83. What, then, does it mean if infant sexuality is itself distorted?

What Frye sees as a “recovery of innocence” in Vala’s Garden is surely not complete. Even if one insists that the triangular relationship between Vala, Tharmas and Enion is innocent, one must admit that Luvah remains oddly distant. Fox observes along with Dike that “Male adults act as constructive powers in the Songs of Innocence only from outside its boundaries.” If Vala’s Garden is likewise “innocent,” it remains so by virtue of the fact that Luvah keeps his distance, and such innocence is one of absence, not recovery. Like Bloom, Harper sees “pastoral vision” as Blake’s attempt to recover a golden age of “organized” and “radical innocence,” which, he says, quoting the poet himself, “‘dwells with Wisdom, but never with Ignorance.’ ” If we may apply Blake’s words to Night the Ninth: ignorance of Luvah (Vala never finds him) prevents this Beulah dream from being radically innocent in the Blakean sense of wise.16↤ 16 Frye, p. 307; Fox, p. 509; and Harper, pp. 113, 121. The Blake quotation is from “Notes Written on the Pages of the Four Zoas,” in The Complete Writings of William Blake, ed. Geoffrey Keynes (New York: Random House, 1957), p. 380.

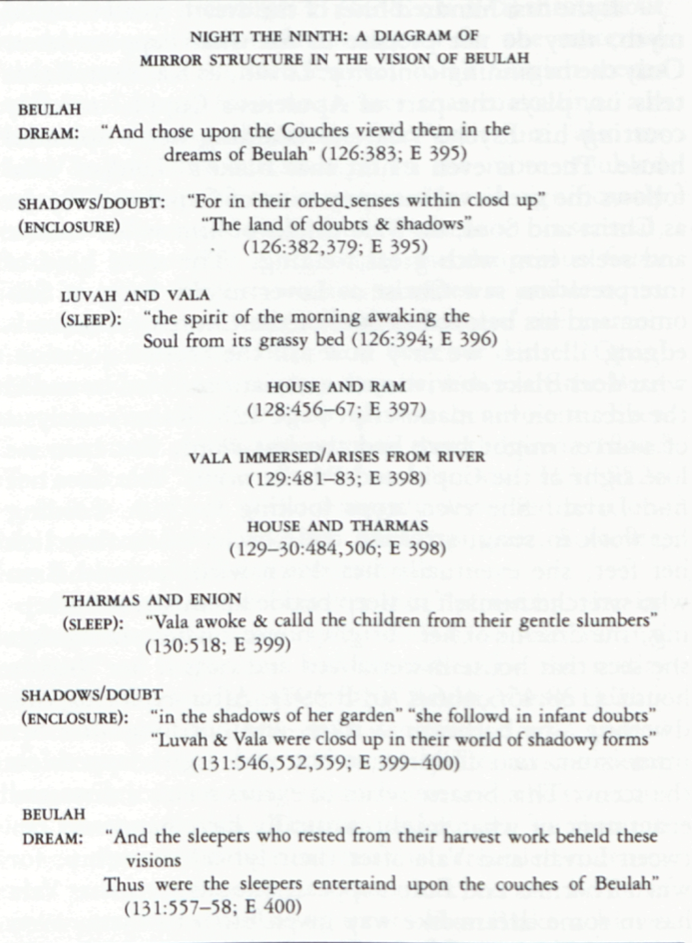

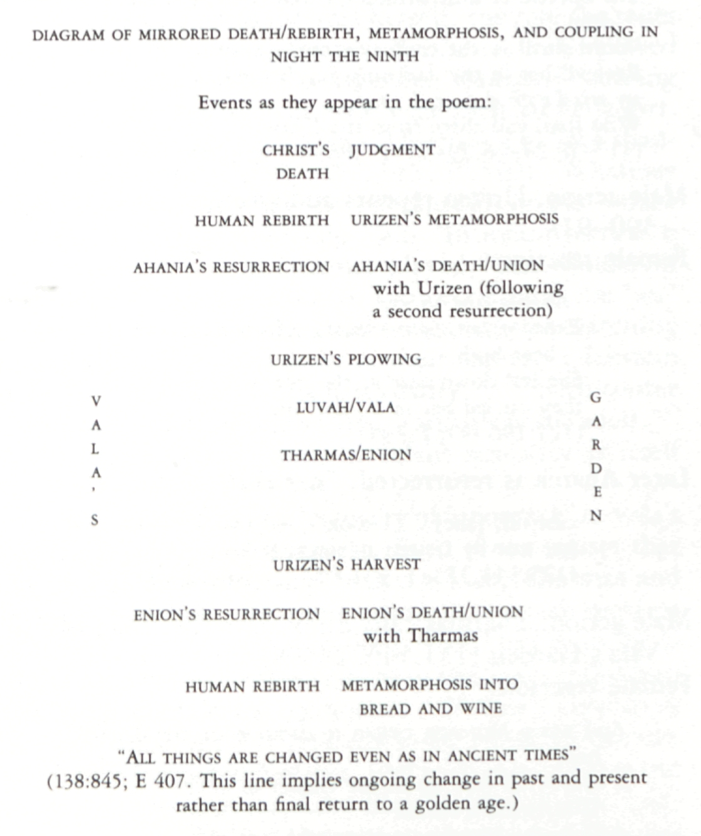

Because Night the Ninth fails its own expectations, it ultimately fails as a “regeneration” of male and female. Beneath its inspired odes to joy, there lies a sexuality darkened by repression and at odds with the usual analysis of this dream as Blake’s vision of perfection. His deferral of consummation, of closure or certainty, demands subtle readjustments in the reader’s anticipations, while the odd repetitive patterns diagrammed below prolong suspense. Can anything claim autonomy within such a structure? One half mirrors another, and, as we shall see, this mirroring pattern is but a microcosmic repetition of the macrocosmic mirroring in Night the Ninth as a whole. Peter Brooks in his analysis of the Freudian “masterplot” observes that the “compulsion to repeat” (a symptom of repression) “can override the pleasure principle” and create a sense “of the demonic” or the

“involuntary.” Blake’s Beucolic dream defers our pleasure in “end” or “meaning” in two ways: within its own boundaries it thwarts or threatens male/female relationships, and as a narrative interruption, it unsteadies the momentous drive of Blake’s cosmic collapse and renewal. For the resting harvesters this dream serves as recreation, but for the reader it can intrude with real incongruity. Frye explains this “long . . . interlude in pastoral symbolism” as the “last spring [which] has now gone through the last summer and is waiting for the harvest of the last autumn” before the fallen world stabilizes into one immutable and redeemed season of joy. His reading sounds compelling, but Blake himself gives us no good reason to think changing seasons will pass away into “one immutable” time. If anything, the Four Zoas lets time go loose in a structural hall of mirrors: definite units of past, present, and future narrative elude us in a disorienting poetic fun-house.17↤ 17 Peter Brooks, “Freud’s Masterplot,” in Reading for the Plot: Design and Intention in Narrative (New York: Knopf, 1984), p. 99; and Frye, p. 307.The dream not only fragments into mirror images within its own boundaries, there are strange reflections of its images and events in Blake’s framing Night as well. Individual “outside” lines correspond[e] to events “inside” the Beulah vision itself. For example, when the Eternal Man declares, Lazarus-like: “I thro him awake begin page 121 | ↑ back to top from deaths dark vale” (122:207; E 391), he anticipates (four pages before the dream) Luvah’s Christ-like command that Vala waken: “Come forth O Vala from the grass & from the silent Dew / Rise from the dews of death . . . (126:388-89; E 395). These puzzling echoes can even give us a new perspective on the ambiguous nature of Vala’s Garden:

Man is a Worm wearied with joy he seeks the caves of sleepThis “outside” or framing passage (from a later speech by one of the Eternals) evokes the dream sequence not only with the word “Veil,” which suggests “Vala,” but with a number of other, even closer associations: Vala, like the Worm-Man, sleeps a cold sleep linked with “death” among the flowers of the Beulah dream (126:389; E 395). Luvah builds her a house equal in splendor to the Eternal’s “walls of Gold” (128:461-63; E 397). And that odd phrase “divided all in families” recalls the sudden appearance, after Vala’s sleep with the Ram, of Tharmas and Enion as children or “shadows,” upon whose necks Vala also falls with embraces. The fantastic way in which elements of the dream appear and reappear in Night the Ninth discourages one’s efforts to piece together a rationale, especially since other reflections turn up again and again throughout The Four Zoas.

Among the Flowers of Beulah in his Selfish cold repose . . .

In walls of Gold we cast him like a Seed into the Earth

Till times & spaces have passed over him duly every morn

We visit him covering with a Veil the immortal seed

With windows from the inclement sky we cover him & with walls

And hearths protect the Selfish terror till divided all

In families we see our shadow born . . .

We fall on one anothers necks more closely we embrace.

(133:627-28, 632-37, 639; E 401-02; emphasis added)

This is not to say that chance alone or even aesthetic patterning explains the mirror effects in Blake’s poem. In one striking instance, the repetitions actually do redound thematic meaning. In Night the First, Tharmas declares that “Males immortal live renewd by female deaths” (5:67; E 302). His vampire law of domination seems born out at the very beginning of the Beucolic dream in Night the Ninth: while Vala lies in “the dews of death” (126:389; E 395), Luvah becomes a kind of God and therefore immortal. Even more remarkable is the fact that other Emanations reenact Vala’s experience before, during, and after the dream. To find the correspondence, one simply reduces the Luvah/Vala dream to a blueprint of male action resulting in female death and resurrection: Luvah hovers, speaks, creates, builds; Vala sleeps in death, awakes to life, is crushed by the idea of another death, and then, reassured by Luvah, finds joy (life) again. Compare that schema (126-27:385, 429; E 395-96) to the following distillation of what happens to the other three Zoa pairs:

Male action: Los tears down the sun and moon: Day of Judgment begins (117; E 386).

Female reaction:

The Spectre of Enitharmon let loose on the troubled deep

Waild shrill in the confusion & the Spectre of Urthona

Recievd her in the darkning South their bodies lost . . .

joy mixd with despair & grief . . .

Who shall call them from the Grave.

(117-18:24-26, 29-31; E 386-87; emphasis added)

Male action: Urizen repents and changes shape (121; E 390-91).

Female reaction:

Ahania rose in joy

Excess of Joy is worse than grief—her heart beat high . . .

She fell down dead at the feet of Urizen . . .

they buried her in a silent cave.

(121:196-99; E 391)

Later Ahania is resurrected, “her death clothes”:

cast off, [she] . . . took

her seat by Urizen in songs & joy.

(125:344, 353; E 394-95; emphasis added)

Male action: Tharmas calls Enion into the “shadows” of Vala’s Garden (131:546; E 399).

Female reaction:

And when Morning began to dawn upon the distant hillsMatching male/female scenes are thus repeated four times, and within the larger frame of general resemblance, there are almost exact repetitions: All four female Emanations vacillate between extremes of “joy” and “grief.” Ahania and Enion both “cast off” “death clothes” after rising from a cave or something like a grave. Conversely, Enitharmon seems to return to the “Grave,” and Vala, as we have seen, descends into a cave-like garden full of death images. Why the Emanations go through such contortions has something to do with Tharmas’s decree that “Males immortal live by female deaths,” but the fact begin page 122 | ↑ back to top that the same kind of thing happens over and over again suggests a relentlessly turning wheel of rise and fall for the females, rather than final reconciliation. Blake’s dark vision of male/female dynamic is, like Ahania’s, a “Self renewing Vision” (122:211; E 391).

a whirlwind rose up in the Center & in the Whirlwind a shriek

And in the Shriek a rattling of bones & in the rattling of bones

A dolorous groan & from the dolorous groan in tears

Rose Enion like a gentle light . . . saying

O Dreams of Death . . . & despair . . .

I shall cast off my death clothes & Embrace Tharmas again . . .

Joy thrilld thro all the Furious form of Tharmas . . .

Mild he Embracd her whom he sought he raisd her thro the heavens.

(132:590-96, 599, 613-14; E 400-01; emphasis added)

Because vision in The Four Zoas is so implacably “Self renewing,” it is also, despite the apocalyptic character of Night the Ninth, in a radical sense never-ending. Horror and joy alternate too often; the pattern of death and resurrection (Ahania ascends to Urizen twice) keeps surprising us. In rhythm, Night the Ninth resembles scherzo more than crescendo. It is difficult to say that the dream has “ended,” or that Night the Ninth has “ended,” when the same things keep happening over and over again in freakish permutations, distorted yet similar. And since these permutations appear all through other Nights in The Four Zoas, how can Night the Ninth convincingly stage a concluding climax? We have already noted the parallel between Tharmas’s domination of Enion in Vala’s Garden to her rape in Night the First. Critics have dealt with it as a redeemed, “innocent” parallel. But since Blake tells us that the children are only “shadows of Tharmas & of Enion in Valas world” (131:556; E 400), one could just as well view their insubstantially childish forms as mere aspects of their whole selves. “Little” Tharmas, after all, pursues his silenced Enion with rather adult persistence. More evidence that what happens between them in Vala’s Garden is not necessarily a final reconciliation (or resolution) lies in Night the Seventh (B), when Vala questions Tharmas much the same way as she does in Night the Ninth: “And She said Tharmas I am Vala bless thy innocent face / Doth Enion avoid the sight of thy blue watry eyes . . .” (93:229-30; E 366; cf. 130:530-31; E 399). A reader determined to make an ending of the Beulah dream, and with it Night the Ninth, could argue that the Seventh Night version merely “foreshadows” the final Ninth Night version. But can we be sure that the Ninth Night version is not, on the contrary, a repeated irresolution?

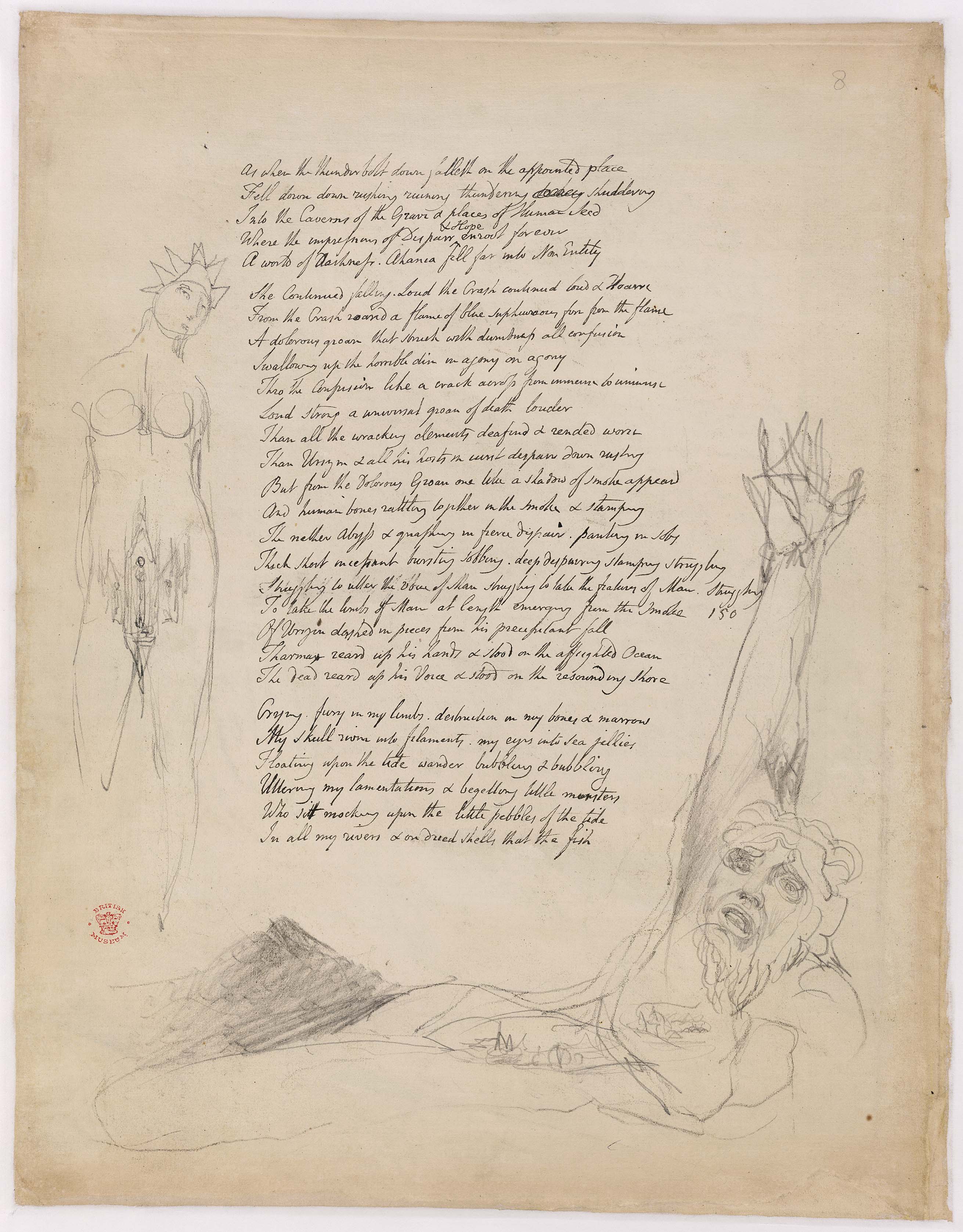

Other repetitions subvert our perception that an earlier event is “over” and that a “later” event supplants it in time, thus resolving whatever issue is (was) at hand. In Night the Second, Luvah creates a garden for Vala as fertile as its Ninth Night double: “I hid her in soft gardens & in secret bowers of Summer / Weaving mazes of delight along the sunny Paradise . . . / She bore me sons & daughters” (27:95-97; E 317). And it is not only Beulah dream images that weave through The Four Zoas as a whole. Compare what Night the Ninth does with Ahania and Vala to this passage from Night the Third: “Into the Caverns of the Grave & places of Human Seed / Where the impressions of Despair & Hope enroot forever / A world of Darkness. Ahania fell far into Non Entity” (44:142-44; E 329). The earlier event, because it is later repeated, keeps us from labeling any similar event, even one in Night the Ninth, as the “last” in an apocalyptic sense.

This subversion of temporal and structural expectations can embarrass scholars who want to make of Night the Ninth the final apocalypse much of Blake’s language seems to herald. Bloom agrees with Frye that the Human Harvest effects an ultimate redemption (i.e., freezing) of time: “After the harvest festival,” he writes, “the vintage begins,” and with it “the new birth of a nature that will cease to be cyclic.”18↤ 18 Bloom, Blake’s Apocalypse, pp. 276, 280-81. This reading loses ground in the face of Night the Ninth’s astonishing ending, an ending so gigantically “cyclic” that it repeats the very beginning of The Four Zoas:

. . . Urthona rises from the ruinous wallsThe words after “intellectual War” do proclaim a new order at the “End of The Dream” (139; E 407), but since “intellectual War” began Night the First, as well, begin page 123 | ↑ back to top might we not suspect that Blake’s “Fall” (the separation of the Zoas) will happen again as it did before? The very beginning of his vision and Night the First—“The Song of the Aged Mother which shook the heavens with wrath / Hearing the march of long resounding strong heroic Verse / Marshalld in order for the day of Intellectual Battle” (3:3-5; E 300)—sounds too much like its end in Night the Ninth for us to say with certainty that the “end” really is an end—or that the “beginning” really is a beginning.

In all his ancient strength to form the golden armour of science

For intellectual War The war of swords departed now

The dark Religions are departed & sweet Science reigns.

(139:852-55; E 407)

Bloom reveals an especially hasty anxiety to impose linearity on Night the Ninth when he asserts that “In this passage [117; E 387] the political vision of Blake reaches its wished-for climax and passes away, to be absorbed into the more strenuous themes of human integration.”19↤ 19 Bloom, p. 268. Since the same revenge on “political” human oppressors (former victims rise up against kings, warriors, etc.) happens over and over again—not just in Bloom’s citation, but on FZ pp. 119, 123, 125 (E 388, 392-94)—one wonders how Bloom’s particular passage can really be the climax that “passes away” to stay away. A more accurate description would admit to a series of climaxes, none of which is obviously more climactic than another.

In effect, what Bloom calls Blake’s “political vision” seems just as “Self renewing” as the poet’s vision of male/female interaction. Can this be a coincidence? Political turmoil and gender conflict both pit the “weak” against the “strong” in a struggle for power. This is why, in my reading, The Four Zoas defies resolution: the troubled dynamic between male and female will not allow Blake’s apocalypse to play itself out into the eternal stasis Frye wants. As long as Vala, trapped in her Garden, remains subject to a god-like Luvah, and as long as Tharmas victimizes Enion, what Bloom sees as mankind’s ultimate redemption will not last. The Four Zoas cannot achieve the wise innocence of Blakean prophesy when male Zoa and female Emanation remain unreconciled.

Night the Ninth’s recurring exchange of feast and destruction, violence and euphoria, prevents us from seizing on any one moment as superseding the others. Like other contrasts in the poem, such eruptions and subsidings compose so relentless a rhythm of alternation that one loses all ordered sense of narrative past/future timing. Blake’s sub-title “Being the Last Judgment” (emphasis added) gives us some warning that his poem reveals not what was or will be the Last Judgment, but what it is: something cataclysmic that rolls on and on in a never-ending present. If the Beulah dream disturbs us because it interrupts what seems to be a headlong rush into the final Universal End (Frye and Bloom’s Apocalypse), so be it. The sooner one admits the disruptive and repetitive nature of Blake’s visionary series (the dream of Vala’s garden being just one model), the sooner one can cease trying to make one’s peace with The Four Zoas and its false peace of male supremacy in the Beucolic idyll. Blake’s vision through all the Nights, including the Ninth, is a “Self renewing Vision,” and such a vision will not let us put it to rest.

REPEATED THEMES AND EVENTS:

Jerusalem/Christ (117, E 386; 122, E 391)

The terror of “Non Existence” (117:5, E 386; 136:739, E 404)

Spirit/body dichotomy (117:4-6, E 386; 125:355-57, E 395)

“Start forth the trembling millions into flames of mental fire” (118:44, E 387; 119:88, E 388)

“Mental fires” burn (125:335, E 394)

Sun destroyed (117, E 386; reappears 127, E 396)

Earth destroyed (117, E 387; 122, E 392)

Trumpet sounds to wake the dead (122:239, E 392; 132:615, E 401)

Oppressors overthrown (118, E 387; 119, E 388; 123, E 392; 134, E 402)

Animals flee (118, E 338); “every species” gathers together (122:238, E 392; 132, E 401)

Insects and plants rejoice (132, E 401; 136, E 404)

Mystery destroyed (119, E 388; 120, E 389; 134, E 403; 135, E 404)

“the Eternal Man Darkend with sorrow” (121:200, E 391; 132:578, E 400; 137:772, E 405)

![5

{7}

{embracd for}

{love}

And then they wanderd far away she sought for them in vain

In weeping blindness stumbling she followd them oer rocks & mountains

Rehumanizing from the Spectre in pangs of maternal love

Ingrate they wanderd scorning her drawing her {life; ingrate} Spectrous Life

Repelling her away & away by a dread repulsive power 100

Into Non Entity revolving round in dark despair.

{Till they had drawn the Spectre quite away from Enion}

And drawing in the Spectrous life in pride and haughty joy

Thus Enion gave them all her spectrous life {in dark despair}

Then {Ona} Eno a daughter of Beulah took a Moment of Time

And drew it out to {twenty years} Seven thousand years with much care & affliction

And many tears & in the {twenty} Every years {gave visions toward heaven} made windows into

Eden

She also took an atom of space & opend its center

Into Infinitude & ornamented it with wondrous art

Astonishd sat her Sisters of Beulah to see her soft affections

To Enion & her children & they ponderd these things wondring

And they Alternate kept watch over the Youthful terrors

They saw not yet the Hand Divine for it was not yet reveald

But they went on in Silent Hope & Feminine repose

But Los & Enitharmon delighted in the Moony spaces of {Ona} Eno

Nine Times they livd among the forests, feeding on sweet fruits

And nine bright Spaces wanderd weaving mazes of delight

Snaring the wild Goats for their milk they eat the flesh of Lambs

A male & female naked & ruddy as the pride of summer

p. 8

Ellis

Alternate Love & Hate his breast; hers Scorn & Jealousy

{They kissd not for shame they embracd not}

In embryon passions. they kiss’d not nor embrac’d for shame & fear 150

{Nor kissd nor em[braced]}

{hand in hand in a Sultry paradise}

{these Lovers swum the deep}

His head beamd light & in his vigorous voice was prophecy

He could controll the times & seasons, & the days & years

She could controll the spaces, regions, desart, flood & forest

But had no power to weave a Veil of covering for her Sins

She drave the Females all away from Los

And Los drave all the Males from her away

They wanderd long, till they sat down upon the margind sea.

Conversing with the visions of Beulah in dark slumberous bliss

Night the Second

{Nine years they view the turning spheres {of Beulah} reading the Visions of Beulah}

But the two youthful wonders wanderd in the world of Tharmas

Thy name is Enitharmon; said the {bright} fierce prophetic boy

{While they} {Harmony}

While thy mild voice fills all these Caverns with sweet harmony

O how {thy} our Parents sit & {weep} mourn in their silent secret bowers](img/illustrations/BB209.1.9.MS.300.jpg)