REVIEWS

Abby Robinson. The Dick and Jane. New York: Dell, 1985. 237 pp. Hard cover, $14.95/Paper, $3.50.

Standard histories of the subject maintain that detective fiction begins in 1841—before the word “detective” is in use—with Poe’s adventures of C. Auguste Dupin as narrated by his sidekick. Later in the century, Doyle successfully imitated Poe’s formula, replacing Dupin and the narrator with Holmes and Watson. In the early 1920s, even before Doyle had quite finished with Holmes, a virtual school of British “mystery” writing, of which Agatha Christie and Dorothy Sayers are central instances, engendered the Poirot-at-the-manor, Sellers-at-the-vicarage kind of story sometimes known as classical or golden-age detective fiction. At nearly the same moment, out of American pulp magazines like the legendary Black Mask came Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler, central writers of the so-called hardboiled school, which used violence, sex, and tough talk to charge up the old elements. The development of the form, or forms, from Poe to the present has been cumulative. All the main branches are still alive and well, though the Holmes line has for the most part become a branch of children’s literature—appropriately enough, since it began as a refinement of the Victorian boy’s adventure story.

As critics like George Grella have shown (“Murder and Manners: The Formal Detective Novel,” Novel 4 [1970]: 30-48, and “Murder and the Mean Streets: The Hard-Boiled Detective Novel,” Contempora 1 [1970], 6-15), the plot structure of detective fiction has always roamed up and down a spectrum between quest romance, for the adventure, and comedy, for the love interest. The Poe-Doyle formula is usually romance, with comic elements, if present, present merely to ratify a successful quest, as when Holmes’s successful battle against man and serpent at Stoke Moran liberates the stepdaughter from the bestial stepfather so she can marry the wimp who had suspected that her fears were all hysterical. In the classical English-style mystery associated with Agatha Christie, structural priorities are more often reversed to favor comedy. Christie’s stories frequently leave one with the feeling that her detectives and sidekicks are knights and squires trapped in comedies of manners, while the process of eliminating suspects one by one almost replaces the episodic confrontations one expects in a romance—and gets, in the running battle between Holmes and Moriarty, for instance. The protracted begin page 38 | ↑ back to top j’accuse drawing-room scenes that often end Christie’s novels, like the mannered love-debate into which Sayers guides Peter Wimsey and Harriet Vane for the conclusion of Gaudy Night, thus seem structurally closer to something out of Congreve or Wilde than to the after-the-fact explanations by Holmes to Watson back at 221B Baker Street, which have more the flavor of ritual heroic bragging after great deeds.

Hardboiled detective fiction returns to romance structures with a vengeance and with irony. Not that irony is missing in the classical formula, which after all uses a corpse to signal the need for a detective, who is by definition tardy. But this irony is often not as ironic as it sounds, since the deceased is frequently guilty anyway, of nasty vices if not of crimes. In any case, hardboiled detection makes the most of the ironic possibilities to create (mainly) subverted romances. The reliable digit with which Hercule Poirot could point out the culprit turns into the fickle finger of a markedly lower-case fate.

Perhaps the most pungent irony turns up in the use of language. Holmes can turn a phrase now and then, and the crafty dialogue through which Christie samples the English class system is a major factor in pushing her plots away from romantic toward satiric comedy. Even more generally, in detective fiction a “red herring” is as often a misleading way with words as a misleading object or event. But it is the role of intellection in detective fiction, both inside, through the thematic emphasis on the mental processes epitomized in the detective’s methods (Poe’s “ratiocination,” Doyle’s “deduction”), and outside, in the reader’s hypothetical participation in these processes, that makes language a focus of attention from the start. The vindication of the hero often amounts to a vindication of someone’s language. The intellectual fantasies through which creative intellection is identified with ruling-class language helped to maintain the deeply conservative bias of early and classical detective fiction.

Scratch intellectual fantasy and you may find intellectual satire. Now, elements of satire had always been present in the language of detective fiction, and at least one recent writer, Rick Eden (“Detective Fiction as Satire,” Genre 16 [1983]: 279-95), has gone so far as to propose that the fundamental structure of the detective story is not romantic or comic but ironic-satiric (in Frye’s sense of the term). The verbal humiliation of police inspectors by detectives like Dupin and Holmes borders on intellectual satire. There is elementary satire in the cogitations and counter-cogitations of Holmes and Moriarty, and, if Doyle had seen fit to explore the implications of “Professor” in “Professor Moriarty,” there would have been a great deal more. It is easy to forget how thoroughly at home intellectual satire is in romance. The battle of wits between Moses and the sorcerers of Pharoah, for the purposes of determining who is the true philosopher, as it were, is a familiar early instance.

All this is by way of providing some context for one of the trademarks of hardboiled detective fiction, tough talk, and its compressed form, the wisecrack. The classical formula of Agatha Christie had evolved quietly out of the materials passed along by Poe and Doyle. But the American hardboiled novel evolves adolescent-fashion, by a series of noisy self-declared reactions, one of the noisiest of which is linguistic. By energizing the linguistic surface of detective fiction as never before, Hammett, Chandler, and followers create an extraordinary amalgam of quest romance with intellectual satire. Predictably, one target of the satire is the language of its own competitor, classical detective fiction, which is by implication the phony language of an effete social order.

The satirical norm characteristic of much hardboiled detection is concocted from a number of already available oppositions, such as the foreign snob versus the American plain dealer, that were long-exploited American literary formulas for relocating true wit in (some version of) the language of the unprivileged: not Lord Peter’s but Sam Spade’s and Philip Marlowe’s. In his essay “The Simple Art of Murder,” which sets some kind of record for native and contradictory theorizing, Chandler was no doubt speaking for many more than himself in claiming that changing the language was part of a sweeping change that writers of his kind of detective story were making from the ideal to the real.

From this vantage point, the easiest satire for hardboiled fiction to offer is the anti-aristocratic sort, where hot air always seems to come from folks with upperclass pretensions: if they grow orchids and read Latin, they’re dangerous. Only a sucker would fail to hear the danger signals in the courtly lingo of Mr. Gutman in Hammett’s Maltese Falcon, and Sam Spade is no sucker. To the extent that upperclass pretensions are intellectual pretensions, the satire offered up in hardboiled detection tends to become anti-intellectual. Which brings us to the ostensible subject of this review, The Dick and Jane, in which, according to Cynthia Heimel, author of Sex Tips for Girls, Abby Robinson “has invented a furiously funny hard-boiled genre of her own.” Brett Harvey, writing for The Village Voice, labels The Dick and Jane “erotic fantasy.” Fair enough, if we don’t overlook the interesting twist that the fantasy here, in the hardboiled tradition, represents itself as reality while characterizing the enemy as fantastical. The enemy, to anticipate in a word, is Blake—not the Blake of An Island in the Moon or the nasty notebook jingles, or even the metaphysical Blake who wants people to change their intellectual lives, but the Kahlil Gibran Blake.

Since, as the blurbs that I quoted indicate, there seems to be some question about what Abby Robinson’s begin page 39 | ↑ back to top book is, let’s try to define The Dick and Jane in relation to the history of its form. It is not hardboiled detective fiction in the manner of Hammett or Chandler, but it extracts elements, especially linguistic elements, from hardboiled detective romance (thus “a . . . hard-boiled genre of her own”) and injects them into a comic plot (thus “erotic fantasy”). Robinson manages this through a series of displacements, more or less as follows. First, she sticks with the convention by which the detective’s sidekick narrates the story, but disregards the conventional reason—controlling the flow of information about the detective—for doing so. At the same time she moves the center of the action away from the detective to the sidekick, whose narration becomes a confessional. The main subject of the confession is not crime and detection but what Chandler called the “love interest,” which he said “nearly always weakens a mystery because it introduces a type of suspense that is antagonistic to the detective’s struggle to solve the problem.” But in The Dick and Jane “the problem” is love and what passes for mystery channels it.

This move has ample precedent. The Dick and Jane is distantly related to The Sign of the Four, in which Doyle wove the love interest of Holmes’s narrator-sidekick into the problem, such that Watson’s courting of Mary Morstan is complicated by crime and investigation until a solution is found, at which point a marriage occurs. A closer relative is Gaudy Night, where Sayers uses a feeble bit of detective interest (the “crime” is persistent vandalism at a women’s college) to motivate her heroine, Harriet Vane, to think about feminist issues, which, at least in the form in which they first occur to her, stand between her and the hero, Peter Wimsey. Sayers uses the hierarchical relationship between detective and sidekick to mirror the hierarchy of conventional marriage.

In the hardboiled mode, the nearest relatives of The Dick and Jane may be the novels of Robert B. Parker, which often move away from romance and detection toward comedy (as in Early Autumn), a shift that makes Parker’s stories eminently adaptable to the requirements of network TV, which long ago began fusing hardboiled romance (with the emphasis on romance) and comedy for double wish fulfillment. The trademark of Parker’s detective, Spenser, is his wisecracking way with words, which is derived from but quite distinct from the wisecracking of Chandler’s Marlowe. In the mainstream hardboiled mystery, the chief purpose of wisecracking is morale building, and as such is related to the cynical wit that soldiers trade at the front line and surgeons exchange over anesthetized patients. Parker turns wisecracking into a virtuoso comic art, much less urgent, not compelled by the situation so much as by the hero’s compulsion to talk. Abby Robinson makes her heroine’s language in this mold. Most of the effect derives from the displacement involved in transferring macho lingo to a female speaker: “The guy was manic-impressive with charisma to burn. He raked me with his beams. Under heavy brows that hung like awnings were laser blues that turned me to Silly Putty. He was harder to face down than a headwaiter” (146).

The wisecracking narrator-sidekick of The Dick and Jane is Jane Meyers, artsy photographer, drawn reluctantly into the mean streets of Manhattan by Nick the dick Palladino, a veteran P.I. (private investigator to you) who occasionally needs a candid camera along to document something or other for their lawyer-boss, Mary Rosenblatt. Their distinctly minor adventures provide the elements of romance. The plot is true to the hard-boiled formula, however, in ironizing the romance: the lawyer, no Perry Mason, is as often on the side of the scumbags as not—just doing a job. Jane, likewise, is a suitably ironic heroine, in fear of life and limb, whose photographic heroism tends to be accidental if any.

The irony, while enough to give a hint of the hard-boiled kind, is played lightly to establish the irreverent, racy mood of contemporary comedy (“A hand slithered into my underpants. Whoever said it was better to give than to receive?” [236]) without any serious downers. If in the romance side of the plot Jane is only an assistant, in the comedy she is the heroine, and the chief conflicts come from her love life, which is centered on her relationship with Hank Gallagher, another photographer, with whom she lives in a Manhattan apartment. According to Jane, their relationship was perfect and “there was nuclear fission to harness in bed” until Hank started reading: “The fishy stuff started when Gallagher got laid off in June. . . . That’s when he took up with Blake. . . . Hank thought he was the berries. He started talking Art—big A—instead of making it. . . . He became Serious. Worse yet, he started critting my photos with highfalutin’ lingo. He said they lacked ‘Fearful Symmetry’ and ‘Radiance.’ Who needed to hear that kind of crapola?” (18). The Dick and Jane gets most of its mileage out of Blake by using him to create what Frye calls the “humorous” characters of comedy whose fixed obsessions blind them to their own motivations and to real life as the comedy envisions it. Hank Gallagher, Blake maniac, is of course the classic comic pedant whose rules for living come entirely out of books, or so he chooses to think, whereas in fact Blake is an intellectual smokescreen for Hank’s sexual doubledealing with Winny, one of those Blakaliens from the G-spot in Ohio, through whom Hank discovers Blake.*↤ * Part of this sentence stolen from Patricia Neill, 13 November 1986.

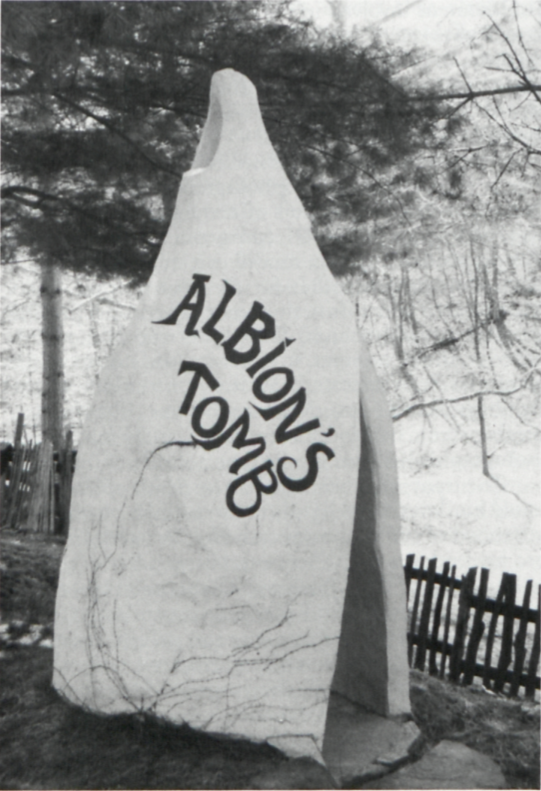

The outward expression of Hank’s inward obsession with Blake is in Ohio, at Golgonooza, sort of a commune begin page 40 | ↑ back to top

Of course the project also brings Hank closer to Winny, on her home turf, and forces Jane to abandon her photographic duties (which, in comic terms, can’t be good). Blake and the Blake groupies of Golgonooza are associated in various ways not only with asceticism, religious cults, and insanity but also with human sacrifice (“I tried not to think about the Blakeans, so I thought about the Manson gang” [177]—but Abby Robinson shows no sign of knowing that “Boucher” was probably pronounced “butcher”), orgiastic sex (“‘Trust us and Blake’s teachings. Gratify Desire. Share in our Creativity and Love.’ Roughly translated: Spread your legs and bop till you drop” [149]; “It was group grope full tilt boogie” [176]), drugs (“Smoke was the Ohio equivalent of chicken soup” [117]; “he drifted over to the couch, lit up a J, and got comfy with Blake’s Apocalypse, some prof’s magnum opus jammed with footnotes” [88]), bad art (“the murals—painted in the only style going” [146]), bad food (“more soybean dishes than Arabian nights” [142]), and, especially, tyranny.

There are various tried-and-true ways out of this comic dilemma: Jane’s fears of Golgonooza life turn out to be illusions derived from the real insanity of life in Manhattan; Jane and Hank distinguish a true Blakeanity from the false uses that the Golgonooza heretics make of it; the horrors of Golgonooza make Hank realize that Blake is for shit and Jane was right all along; Hank and Jane convince the denizens of Golgonooza of the error of their ways and they all get together in a reformed community. Etc.

The Dick and Jane chooses instead the somewhat more extreme solution of giving up on Blake and Blakeans, which means giving up on Hank. The comic excuse for getting rid of the old squeeze is Jane’s late, incredibly late, discovery—back in Manhattan, her territory, doing photography again—of Hank’s hankypanky with Winny. Kiss and make up remains a possibility, but no: “There’s no choice, Hank. We have to make a break. . . . I can’t live your kind of life and you can’t live mine. . . . It’s just the way the cards are stacked. . . . I love you and you love me. What of it? . . . If I put up with this arrangement, I’d be playing the sap for you. . . . Part of me wants to say to hell with the consequences, just go along with this Blakean drek. . . . But I’m no Blakette, though I tried. I’ll miss you and I’ll have some rotten nights, but that’ll pass” (220-21).

It’s not for nothing that Jane guides us through these bits of parting dialogue with literary signposts: “I copped some of the tough guy talk from pulpster David Goodis. . . . It was lucky Hank wasn’t familiar with The Maltese Falcon since I lifted most of my lines from Sam Spade’s windup with Brigit [sic] O’Shaughnessy. Hammett’s begin page 41 | ↑ back to top dialogue got me over the rocky spots” (221). Jane’s erotic conflict coincides with an intellectual conflict. On the horns of her dilemma are two originary texts, Blake and Black Mask, and the comic conflict is resolved in terms of that textual conflict: “Saturday, 8:49-9:34 A.M.: Attempt to read The Visions of the Daughters of Albion. Saturday, 9:35-10:39 A.M.: Sneak copy of Horace McCoy’s No Pockets in a Shroud out of suitcase” (170).

Hank speaks “Blake-speak” (100), Jane speaks hardboiled. A comedy written in the most tolerant spirit would find some way of reconciling them, and in her most accommodating moments Jane can sling some Blake herself:

“Listen, Jane.” He sounded serious. “Are you sure you still want to go [to Golgonooza] tomorrow?”But Blake and hardboiled aren’t to be reconciled:

“‘The apple tree never asks the beech how he shall grow; nor the lion, the horse, how he shall take his prey.’ Winny’s visit convinced me.” Boy did it.

“It did?” Golden Boy seemed startled.

“‘The thankful receiver bears a plentiful harvest.’ Right? So now I have a better idea about what Golgonooza’s all about.” . . . I felt guilty and horny. “Expect poison from the standing water,” old Willy Boy warned. Better to act. I did. On Gallagher. Most of the night. (131-32)

“Hank, we can’t stay here.”In a world where women are frails and skirts, nobody’s likely to get away with calling them daughters of Albion. The opposition is kept from being quite absolute by the double capability of photography for documentation and art, which allows it, and Jane, to occupy some middle ground of art-in-life. Nonetheless, the P.I., Palladino, who has no truck with fancypants art photogs but a real need for some real photography, turns out to be the only one with enough insight to see through the intellectual pretenses of Jane’s Blake-nut boyfriend. I’ll honor the conventions of mystery reviewing enough to keep quiet about the ending, but clearly the answer to Jane’s problems must come from the pages of the hardboiled text. Sure enough, at a climactic feast in the comic tradition . . . presided over by Palladino’s earthy wife Gina . . . with a mystery guest at the dinner table in the tradition of golden-age detection. . . .

“‘Listen to the fool’s reproach.’ ”

“Fuck you.” (165)

Who might read The Dick and Jane? Some reviewers have said they found it engaging, and no serious historian of the wisecrack can afford to miss it. What modest strength The Dick and Jane can claim is in the playful rhythms and diction that give the heroine a certain winning charm. Even that pleasure subsides once you’ve adjusted to the idea of hardboiled yammer gushing out of the frail’s softboiled gash. The satire on the Blakeans of Golgonooza, which would be pretty deadly for anyone coming in cold, may be readable for students of the uses of Blake in modern culture. If they swear they won’t blame me when they find out that The Dick and Jane has no puzzle, local color, violence, or titillation worth the name, I would recommend it to Blake scholars and mystery buffs looking for something to get them through a long layover in the People Express terminal at Newark, or through a summer vacation at a certain spiritual community in America’s heartland. But no guarantees.