review

Stanley Gardner. Blake’s Innocence and Experience Retraced. London and New York: Athlone Press and St. Martin’s Press, 1986. xviii + 211 pp. illus. $27.50.

Attempting to trace the Songs back to some origin or source, this book offers a Blake who first acclaims “the work of enlightened charity” undertaken by his parish in the 1780s but who subsequently, owing to the failure of that experiment in welfare, turns with “cold fury” to epitomize “the desolation” in Songs of Experience. Along the way we have a provocative revisionist account of “Holy Thursday” (SI) and become well acquainted with how things sound “to [Gardner’s] ear” and look “to [Gardner’s] eye.” Working our way back to “the groundwork of a vision” (14), “the visionary groundbase” (47), begin page 28 | ↑ back to top we can even find ourselves “As we read, sitting beneath the chimney newly swept in Golden Square” (65).

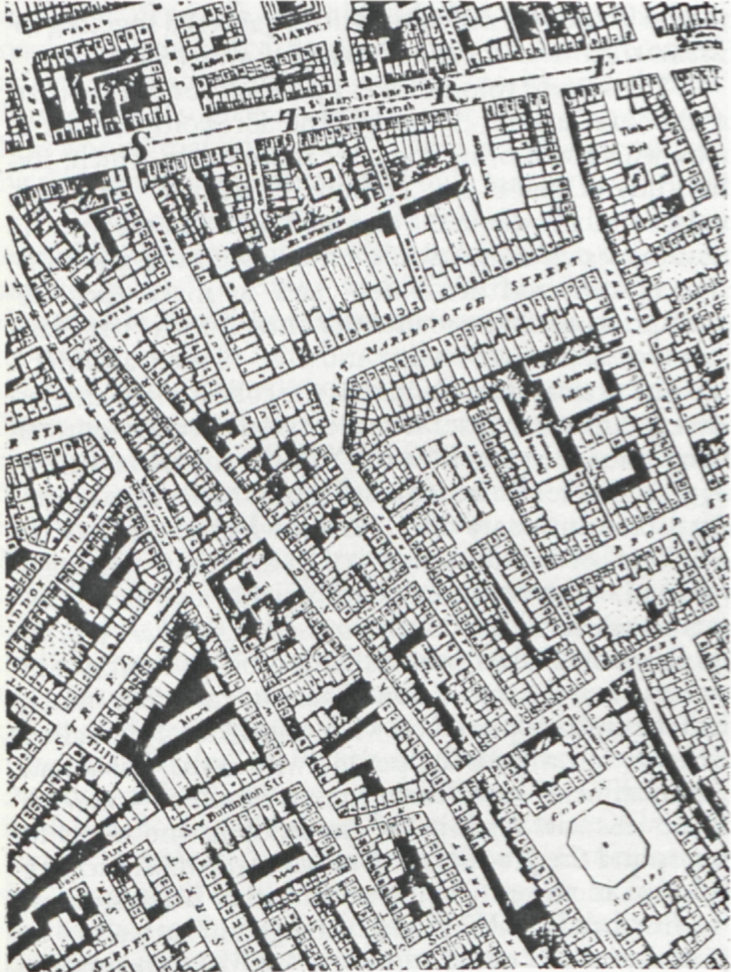

For Gardner, the “geographical and social matrix” for most of Songs of Innocence is to be located in two new forms of charity established by the parish of St. James. The first was the practice of transferring pauper children and infants out of the city to be nursed by cottagers at then rural Wimbledon:

The effect of the policy . . . was dramatic. The Annual Registers of the Parish Poor for 1783 tell us that twenty-four of the fifty infants nursed by their mothers in St James’s workhouse died before the year was out; and that in the same year the nurses at Wimbledon took care of seventy-seven children from the workhouse, with such ‘skill and attention’ that only two died. A year or two later, Blake had written the first draft of ‘Nurses Song,’ and then slipped it into An Island in the Moon. (7)Still more important for Gardner’s account is the school for pauper children which “the Governors of the Poor” for St. James established on King Street in 1782. Blake can be strikingly associated with the school through surviving records of payment to “Mr. Blake Haberdasher”—first the poet’s father, James, and then his elder brother, also James, who evidently took over the business on the father’s death in 1784. In the last weeks of 1784, Gardner reminds us, Blake and James Parker opened their printshop at 27 Broad St., next door to the Blake family home and haberdashery. Gardner reports that “no other London parish even remotely approached St. James’s in the vigour and consistency with which it took practical care of its pauper children” (14) and finds in this communal expression of “brief and untarnished charity” the genesis of Songs of Innocence. In these poems Blake gives “a conclusively social rather than matrimonial emphasis” to the nurture of children, and “It seems to be an insistence we must respect” (24).

The consequences of Gardner’s reading surface most dramatically in the account of “Holy Thursday” in Innocence. While “our persistent misreading of the nature of charity schools” (30) has made us uncomfortable with the poem’s place in Innocence, it is clear to Gardner that Blake “added the illustration to insist that we take ‘Holy Thursday’ . . . straight, without benefit of our own brand of retrospective enlightenment . . .” (35). One piece of evidence in this view is the poem’s reference to “wise guardians of the poor,” which Gardner can associate with an actual parish office (re-)instituted in 1782: “Blake’s reference to this renewed and repeatedly recorded office of Guardian of the Poor seems to me too topical and too immediately recollective of an enlightened reform to be ironic or accidental” (41). Gardner corrects a common misapprehension in pointing out that the anniversary meeting of the charity-school children (“clearly an occasion Blake had shared”) took place “neither on Ascension Day or on Maundy Thursday, the two possible holy Thursdays of the church calendar” (35) but on some other late-Spring Thursday—or, once, Wednesday. This leads Gardner to suggest that the name “Holy Thursday” had been “used ironically as a gibe by some of the circle of friends Blake caricatured in An Island in the Moon” (where the first draft of the poem appears), but that Blake took over the term for his own purposes. (Perhaps the formula that “Thursday’s child has far to go” may be lurking around?)

The poem is at the center of Gardner’s conception of Innocence, and the book’s penultimate page argues again that “the lamb first entered Blake’s creative imagination when he heard the expectant murmur of the charity-school children in St. Paul’s. He went on to give the destitute child angelic status, and his neighbours the admonition, ‘cherish pity’ ” (157). But the complete admonition reads, “Then cherish pity, lest you drive an angel from your door” (contra Keynes, Erdman, and Bentley, Gardner reads “Then cherish pity; . . .”), and the fact that these messengers (“angels,” etymologically) are being walked away from our individual doors reflects eerily on the nature of that “human abstract” pity the speaker would have us “cherish.” Such various voices and possibilities are not for Gardner, and, asserting themselves, they leave “an odd sense of contradiction and unease”: “‘The Little Black Boy’ is a profoundly ambiguous poem, and the ambiguity is deepened, not resolved, by the illustrations. Its relation to the rest of Songs of Innocence is uneasy, and yet it provides Blake with the only means to hand by which a necessary dimension is added to the book” (63). While that “necessary dimension” is never clarified, the accompanying argument suggests that if “contemporary circumstances behind the poem” (62) could be identified, ambiguity might be lessened, if not resolved. The difficulty (“profound ambivalence,” 64) is that, instead, here Blake writes of “the imagined state, which both generates the poem and is expressed in the poetry itself” (62). That “the imagined state” should prove so problematic will seem to some an apt comment on the entire enterprise of “retracing” Innocence and Experience.

Gardner’s research in the Westminster archives adds some useful information about Blake’s milieu; but one can regret that such an ambitious project did not extend further into the wide range of secondary material. Particularly striking for a book which argues that “the primary motivation” of the Songs lies “in the assumptions which hung in the air [Blake] breathed” (144) is the lack of any reference to Heather Glen’s quite different version of those assumptions in Vision and Disenchantment (1983). One may have reservations as well about an argument which inserts “universally” before quoting the OED’s comment that “willow” is “taken as a symbol of grief” (100), or baldly states “The essence of Innocence” (107), or hears Blake speaking in propria persona “for the only time”—in two separate poems (“London,” begin page 29 | ↑ back to top 118; “On Another’s Sorrow,” 76)—or characterizes “deep” as “that most sinister of all words” (98). But in its relentless contextualization Gardner offers a salutary[e] antidote to any who would seal Blake up in mere “textuality”: “A year before Blake issued Songs of Experience a chapel was built ‘on the green’ in South Lambeth” (139). It cost £3000, “financed by the issue of sixty shares of £50 each, every shareholder being entitled to four seats,” and Gardner even reproduces a 1793 watercolor of it, complete with cattle fenced off in the foreground pasture.