review

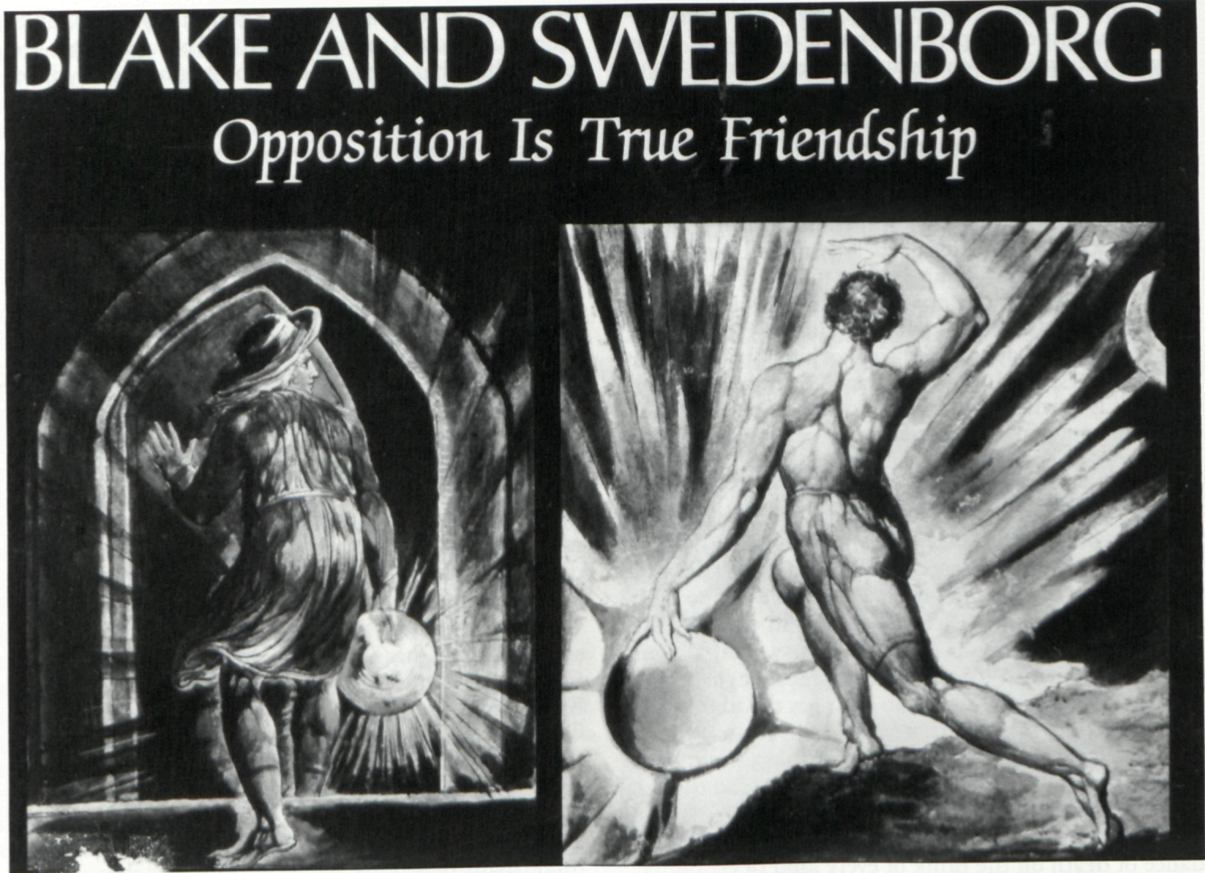

Harvey F. Bellin and Darrell Ruhl, eds. Blake and Swedenborg: Opposition Is True Friendship. New York: Swedenborg Foundation Inc., 1985. 157 pp. $8.95.

The subtitle of this anthology, “The Sources of William Blake’s Arts in the Writings of Emanuel Swedenborg,” is more precise about its contents than its allusive title. The subtitle has the virtue of reminding us of the demonstrated connection between Blake’s poetry and engravings and the theosophical writings of Emanuel Swedenborg.

This does not come as a surprise, and apart from some introductory surveys the anthology presents very few articles that have not been published elsewhere. A good starting-point is Morton D. Paley’s paper “A New Heaven Is Begun: Blake and Swedenborgianism” (15-34), which is not only the first but also the best contribution to the book. There are in all thirteen surviving books in which Blake made notes, and among those, three had been written by Swedenborg: Heaven and Hell, Divine Love and Wisdom and Divine Providence. begin page 159 | ↑ back to top The first Swedenborgian conference in London in 1789, in which Blake and his beloved Catherine registered among the participants, was the only assembly we know him to have attended. Of similar importance are Blake’s attacks on Swedenborg in his marginal notes in Divine Providence and the satire The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. When dealing with a well-informed critic like Blake a negative reading often indicates influences as interesting as those emanating from the submissive attitude of a follower.

The conference in April 1789 unanimously accepted forty-two theological theses; they are available in a later section of the anthology. Thus it is easy for the reader to find out what Blake could accept at that time as a foundation for his creed. It is a matter of course that he firmly believed in man’s free will, but Paley emphasizes that he also accepted Swedenborg’s famous Nunc licet. “That Now it is allowable to enter intellectually into the Mysteries of Faith” (Vera Christiana Religio, n. 185).

Obviously Blake had already strained the meaning of Swedenborg’s words in a direction that did not correspond to the intentions of the master. Paley takes one of the marginal notes in Heaven and Hell as an example. According to Blake’s reading, hell becomes something negative, a kind of mistake for heaven, which is of course in line with his own passionate conception of unity but not in accordance with Swedenborg’s thinking. In a similar way Blake tried to stress the unifying elements of Swedenborg’s doctrine of correspondence restraining everything that separates nature from the spiritual world: i.e., an attitude toward reality which later he was to express by the wonderful metaphor of looking through the eye but not with it.

As Paley correctly observes, Blake had no reason for attacking Swedenborg as a representative of a doctrine of predestination “more abominable than Calvin’s.” In a number of texts Swedenborg firmly repudiated all ideas of a divine predestination. God is omniscient, however, knowing the final destination of all individuals, but this should not prevent man from making use of his liberum arbitrium. From an omniscient point of view it may be impossible to divide between predestination and prediction but not from a human one, and man’s free will is a basic element in Swedenborg’s theology.

But Blake found this well-known method of dealing with the theodicy problem unacceptable, and there were other reasons which forced Blake to dissociate himself from the New Jerusalem of the Swedenborgians and to build his own. First Paley mentions the attitude to the French revolution. For Blake, the upheavals in France were a cause for rejoicing, but the New Church people were anxious to condemn them completely. Some internal conflicts made Blake indignant, e.g., the expulsion of a number of members, among them two remarkable Swedes, Carl Bernhard Wadström and August Nordenskjöld, because of a controversy about Swedenborg’s view of concubinage presented in De amore conjugiali (1768). The rather macabre opening of Swedenborg’s tomb in 1790, or more precisely the motivation for it, had a similar effect on Blake. As Paley reports, he fiercely alluded to these events in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell.

However, this formidable satire does not represent Blake’s last words about Swedenborg. On the contrary, Paley shows very convincingly that there are many Swedenborgian influences to be found in Blake’s later works, in details as well as in general evaluations. The list given in Jerusalem of the books of the Bible, which contain the internal sense of the Word, is exactly the same as the one Swedenborg established. Swedenborg also inspired Blake’s view of history as a series of “churches” more or less in a state of decomposition, and gave him the fancy piece of information that the oldest Word is preserved in Great Tartary. Swedenborg himself referred to his angelic interlocutors, but a skeptical reader probably prefers a number of contemporary texts as possible sources for this statement, which of course cannot be scientifically verified.

Following Paley’s learned essay is a survey of a more popular kind written by one of the editors. Bellin’s way of presenting the relations between Swedenborg and Blake indicates that the author is a prominent TV-producer with a keen eye for what is dramatically and pictorially efficient. Blake’s art contains many qualities of that sort and Bellin’s contribution includes a number of impulses for the analysis of the artist’s Swedenborg inspiration. The author lays the main stress on the doctrine of correspondence as a liberating as well as a structuring force in Blake’s attempt to visualize his ideas of a psychic universe, and this seems generally reasonable. But when it comes to details Bellin hardly succeeds in dealing with the wide gap between the rationalistic factors of Swedenborg’s own presentation of the doctrine and Blake’s distinctive mythology. On the other hand, he certainly exaggerates Swedenborg’s contributions as a scientist, which is as characteristic as understandable in most Swedenborgian contexts. The rather unfortunate effect of this apologetic attitude is that Swedenborg will be seen as a less problematic, and consequently less interesting, author than he becomes if one tries to understand him as representing some esoteric trends in eighteenth-century thinking.

In one of his footnotes Paley refers polemically to Kathleen Raine’s book Blake and Tradition (1968). Her chapter on Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience is reprinted in the anthology, but Paley’s critical reference concerns a neoplatonic interpretation in a later part of Raine’s book. However, the platonic tradition has been invoked also in this chapter, where Swedenborg’s begin page 160 | ↑ back to top “symbolism” is presented as a variation of platonic thinking. This is certainly true of all “symbolic” languages in European philosophy, but this very fact makes precise distinctions more important. Even if Raine is of the same opinion, she has put almost all emphasis on Swedenborg’s rather arbitrary methods for interpreting Holy Writ. The most fascinating elements of Swedenborg’s thinking are not given their due attention, e.g., that the doctrine of correspondence represents a substitute for the mathematically conceived universal language of which some of his greatest predecessors in the seventeenth century had been dreaming. Swedenborg’s visions bear the stamp of decades of scientific work and daring speculations within the framework of contemporary science about the hidden structure of nature. In Raine’s view “there is no literary value in Swedenborg’s symbolism, and nothing could be less poetic than the ‘visions’ of that sage,” but she has presented most unsatisfactory reasons for her evaluation. On the contrary, Swedenborg’s works as a whole display deep intellectual and emotional qualities resulting in a personal combination of enlightened rationality and romantic forebodings. Blake must have felt the intensity behind Swedenborg’s systematic rigidity, and he reacted in the same manner as so many other artists and poets: sometimes he found these qualities attractive and inspiring; on other occasions he was repelled by the master’s conventionalities in concepts and style.

The second contribution to the anthology by Kathleen Raine is a lecture held in Paris in 1985 called “The Human Face of God.” Her subject here is the concept of God in Swedenborg’s and Blake’s works in comparison with Jung’s Answer to Job. From a literary point of view this lecture is interesting as an attempt to prove that the influence of Swedenborg appears to have been stronger in Blake’s later works than in those from the 1790’s. Since this is a hypothesis contradictory to the mainstream of Blake scholarship it should be considered. But the argumentation here can hardly be regarded as well founded. In order to prove the hypothesis a much more penetrating analysis of Swedenborg’s and Blake’s use of the concept “the Divine Human” will be necessary. Still, Raine’s edifying discourse contains many valuable impulses for future research.

The second section of the anthology, “Historical contexts,” includes the report of the London conference in 1789 mentioned above and a study by Raymond H. Deck, Jr. of Charles Augustus Tulk (originally published in Studies in Romanticism 1977). This is a solid historical account of one of Blake’s nineteenth-century patrons, who probably had some importance for the artist’s later opinions of Swedenborg. Tulk’s parents took part at the London conference in 1789, but their son preferred to remain outside Swedenborgian sectarianism. Still, he was well read in the master’s writings, and he was also one of the founders of a society for printing and publishing these works in 1810. As the Swedenborg Society, this association has done great work in promoting information about them and is still doing so.

Tulk was a gentleman of independent means, who devoted his time to politics and his reading of Swedenborg. He also supported William Blake in different ways. It was probably their common friend John Flaxman who enticed Tulk to buy some of Blake’s works around 1815. In February 1818 he lent Coleridge a copy of the poet’s Songs, and the learned critic immediately identified some essential Swedenborg influences in them. On a later occasion he also arranged a meeting between Coleridge and Blake. The author has also given convincing reasons for the attribution of an article in 1830 to Tulk, which describes this encounter: “Blake and Coleridge, when in company, seemed like congenial beings of another sphere, breathing for a while on our earth; which may easily be perceived from the similarity of thought pervading their works.”

The concluding section of the anthology is called “Swedenborgian Postscripts.” It consists of two articles and one lecture by New Church men, who illustrate different attempts at explaining Blake’s complicated relations to Swedenborg from their particular point of view. In that respect they outline a reception history, to which this beautiful anthology itself is the latest contribution. The question marks in its margins should not discourage anyone interested in William Blake’s art from reading this book. It certainly deserves many readers both within and outside of the New Church tradition, where the artist has caused many sorrows but also great pride.