MINUTE PARTICULARS

“Under the Hill”

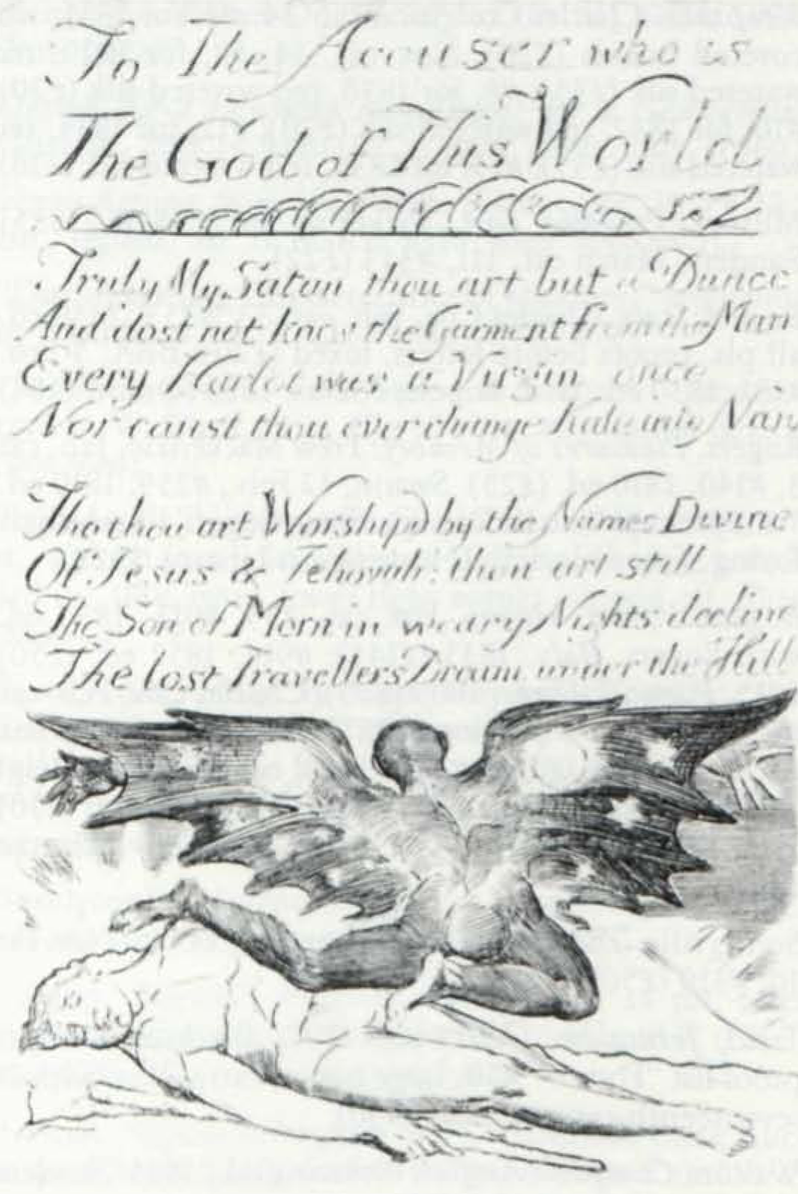

Despite frequent citation of “To the Accuser who is The God of This World” as “one of Blake’s most perfect short poems” (Bloom 435, cf. Damrosch 356), no one seems to have remarked a probable source for the poem’s concluding reference to (or, that) “The lost Travellers Dream under the Hill.” Alicia Ostriker writes that “The lost traveller is man, and Satan is but his dream” (1040); W. H. Stevenson sees an “allusion to such common folktales as that of True Thomas, or Rip Van Winkle, in which a mortal is carried into a fairy hill” (845); Damon, perhaps choosing not to be too explicit, refers to “the mistaken ideals of those still wandering in the wilderness of life” (87).

But as the “prologue” of For the Sexes: The Gates of Paradise is preoccupied with images involving the Sinai revelation of Exodus (“Sinais heat,” “his Mercy Seat,” “Jehovahs Finger” writing the Law), it’s not surprising to find that event in the “epilogue” as well. Moses’ fellow travellers, Blake could read (reading white where we read black), are finally lost “under the hill.” For in William Tyndale’s translation (does anyone imagine Blake limiting himself to “the Authorized Version”?), “Moses brought the people out of the tētes to mete with God. and they stode vnder the hyll” (Ex 19:17). Later, according to both Tyndale and the AV, Moses builds “an altar under the hill” (Ex 24:4). And Tyndale’s Deuteronomist has Moses remind the people that “ye came ād stode also vnder the hyll [AV: ‘under the mountain’] ād the hyll burnt with fire” (4:11). “Under” in these translations of the common Hebrew preposition “tahat” (“under”) has the evident denotation of “position at the bottom or foot of something” (s.v. OED I.7, cf. c. 1402 and 1662), though some literalist rabbis suggested that YHWH uprooted the mountain and suspended it over the Israelites to encourage acceptance of the Torah (Kasher 9:90). They submitted and—Blake seems to say—remained asleep.

The illustration offers another comment alongside the striking representation of psycho-sexual fantasy (Hilton 169). For the sleeping figure (Moses and his rod might suit the context) is graphically under a design that suggests an image of Lucifer, “The Son of Morn”—or, in terms of the text, “the Hill.” Here we encounter a marvellous particular instance of how powerful texts

Works Cited

Bloom, Harold. Blake’s Apocalypse: A Study in Poetic Argument. 1963. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1970.

Damon, S. Foster. William Blake: His Philosophy and Symbols. 1924. Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1958.

Damrosch, Leopold, Jr. Symbol and Truth in Blake’s Myth. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1980.

Erdman, David V., annot. The Illuminated Blake. Garden City: Anchor-Doubleday, 1974.

Hilton, Nelson. “Some Sexual Connotations.” Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly 16 (1982-83): 166-71.

Kasher, Menachem M., ed.[e] Encyclopedia of Biblical Interpretation: A Millennial Anthology. 9 vols. 1953. New York: American Biblical Encyclopedia Society, 1979.

Ostriker, Alicia, ed. William Blake: The Complete Poems. Penguin English Poets. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1977.

Stevenson, W. H., ed. Blake: The Complete Poems. Annotated English Poets. London: Longman, 1971.

Tyndale, William. William Tyndale’s Five Books of Moses Called The Pentateuch. 1884, rpt. of 1530. Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP, 1967.