article

begin page 20 | ↑ back to topBlake’s Healing Trio: Magnetism, Medicine, and Mania

When William Blake returned to London from his “three years Slumber” at Felpham, he initially found sympathetic friends as he pursued his “visionary studies.”1↤ 1 David V. Erdman, ed., Complete Poetry & Prose of William Blake, newly rev. ed. (New York: Doubleday/Anchor, 1982) 728-29. Hereafter cited as E. Blake participated throughout the 1780s and 90s in an eclectic network of illuminés, which included Swedenborgians, Freemasons, and Cabalists who shared his interest in animal magnetism spirit-communication, and erotic trances.2↤ 2 Marsha Keith Schuchard, Freemasonry, Secret Societies, and the Continuity of the Occult Traditions in English Literature (Ph.D. dissertation, Univ. of Texas at Austin, 1975); The Men of Desire: Swedenborg, Blake, and Illuminist Freemasonry (forthcoming). In 1804 he apparently renewed his acquaintance with several theosophers, who continued their secret meetings and occult studies over the next decade. Unfortunately, the fragmentary evidence for this collaboration comes from an embittered notebook poem (c. 1808-11), when Blake accuses his friends of cowardly withdrawal from their mutual studies. Compressed into eight hostile lines, Blake’s mental distress and spiritual commitment reveal the radical daring of his visionary enterprise:

Cosway, Frazer & Baldwin of Egypts Lake

Fear to Associate with Blake

This Life is a Warfare against Evils

They heal the sick he casts out Devils

Hayley Flaxman & Stothard are also in doubt

Lest their Virtue should be put to the rout

One grins tother spits & in corner hides

And all the Virtuous have shewn their backsides

(E 505)

The first three friends—Cosway, Frazer, and Baldwin—were drawn together by shared interest in animal magnetism, the bizarre pseudoscience that played a role in its day equivalent to Freudian and Jungian Psychology in our own.3↤ 3 Robert Darnton, Mesmerism and the End of the Enlightenment in France (Harvard UP, 1968); Clarke Garrett, Respectable Folly: Millenarians and the French Revolution in France and England (Johns Hopkins UP, 1975). Animal magnetism was a “modern” version of ancient Cabalistic meditation techniques, merged with Hermetic, Paracelsan, and astrological theories of man as microcosm. Seventeenth-century speculation on the universal magnetic fluid was updated with new theories of electricity. Developed by Dr. Franz Anton Mesmer into a methodical science of hypnosis, trance, and nervous catharsis, magnetism became a kind of countercultural therapy and religion to the restless, millenarian spirits of the revolutionary decades. Despite its “holistic” claims, the new magnetic religion split into rival schools which accused each other, respectively, of materialistic atheism and occultist fanaticism. Blake and his three friends were not immune to these bitter though often comical quarrels.

Richard Cosway (1740-1821), the fashionable miniature painter, was one of Blake’s oldest friends. Fascinated by magic, alchemy, and Cabala, Cosway was intimately acquainted with radical Freemasons and millenarian illuminés in Europe as well as England.4↤ 4 George Williamson, Richard Cosway, rev. ed. (London: G. Bell, 1905); Frederick Daniell, A Catalogue Raisonée of the Engraved Works of Richard Cosway, R. A. (London: F. B. Daniell, 1890). Cosway joined the Swedenborg society in 1783-84, at a period when it was dominated by French and Swedish Freemasons who believed that Swedenborg himself was a Cabalist, alchemist, and Mason.5↤ 5 “Mr. Cosway, Painter in History,” is listed by C. F. Nordenskjöld as a member of the group in 1783-84. Unpublished list in Academy Collection of Swedenborg Documents, Academy of the New Church, Bryn Athyn, PA. On Freemasonry and early Swedenborgianism, see Martin Lamm, Upplysningstiden Romantik, 2 vols. (Stockholm: Hugo Gebers, 1918) 1: 63; R. L. Tafel, “Swedenborg and Freemasonry,” New Jerusalem Messenger (1869): 266-67. Working closely with the London society were Dr. Benedict Chastanier and the Marquis de Thomé, who founded the Masonic rite of Illuminés Théosophes in London and Paris.6↤ 6 Karl-Erik Sjoden, “Swedenborg en France,” Stockholm Studies in the History of Literature, 27 (1985): 10-40. They believed that Mesmer took his theories from Swedenborg and then perverted them into a materialistic science.7↤ 7 Intellectual Repository, 2 (1874-75): 191-98; Journal Encyclopédique, 6 (1 Sept. 1785): 310-20. Cosway and the London group agreed, and John Flaxman still believed this in 18238↤ 8 Henry Crabb Robinson, Diary, Reminiscences, and Correspondence, ed. Thomas Sadler, 2 vols. (Boston: J. R. Osgood, 1871) 1: 494-96. .

In 1784 a French governmental commission exposed animal magnetism as a fraud, which only drove its disciples into more radical defenses of the new science.9↤ 9 Darnton 62-66. A disgusted Mesmer traveled to England in August 1785, hoping to establish a Mesmeric Masonic lodge.10↤ 10 See W. R. Dawson, ed., The Banks Letters (London: British Museum, 1958) 66, as a corrective to Vincent Buranelli, The Wizard from Vienna (New York, 1975) 182. But he found his rivals already dominating the popular magnetic stage. Mesmer faded from the English scene, while his apostate pupil, Dr. John Bonniot de Mainaduc, instituted a decade-long reign.11↤ 11 The Lectures of J. B. de Mainaduc, M.D. (London: printed for the Executrix, 1798). Copy in Royal College of Surgeons, London. Includes list of paying students. I am grateful to Jonathon Miller, M.D., for informing me of this copy. Cosway and his Swedenborgian friends became Mainaduc’s earliest and, for a while, most ardent disciples. Born in Ireland to a French Protestant family, Mainaduc studied medicine in London in the 1770s under Drs. William and John Hunter, George Fordyce, and other eminent physicians. In 1782-84, he studied in France where he was caught up in the Mesmeric enthusiasm. When he offered Mesmer 200 guineas for his secret, the German doctor haughtily refused.12↤ 12 John Martin, Animal Magnetism Examined (London, 1790) 5-6. Mortified, Mainaduc turned to Dr. Charles Deslon, an early champion of Mesmer, who developed a different technique. Mainaduc claimed that Deslon raised the science beyond Mesmer’s “crude state.”

begin page 21 | ↑ back to topReturning to London in 1785, Mainaduc introduced magnetism into his medical treatment, drawing a clientele initially from his large midwifery practice. He soon deviated from the materialistic gadgetry of Deslon’s style (tubs, tubes, rods, etc.), and declared a purely spiritual form of magnetism. A Freemason himself, Mainaduc attracted the interest of Swedenborgian Freemasons who appreciated his spiritualistic approach in which “divine influx” aided the cures. On 12 December 1785, he initiated Chastanier into “this Modern Magical Science.”13↤ 13 Benedict Chastanier, A Word of Advice to a Benighted World (London, 1795) 30-31. For the next ten months, Chastanier served as Mainaduc’s chief assistant at his lavish clinic in Bloomsbury Square. Attacked by a Mesmeric rival, Dr. John Bell, as superstitious and unscientific apostates, Mainaduc and Chastanier defended themselves by claiming to perform the same kind of spiritual cures as Christ and his disciples.14↤ 14 Daniel Lysons, Collectanea, A Scrapbook of Eighteenth-Century Newspaper Clippings in the British Museum, 1: 156-63 on animal magnetism. Also, John Bell, A New System of the World (London, 1788). The two illuminés then invited “twenty gentlemen of distinction” to hear their lectures, in which Paracelsus, Fludd, Kircher, and Swedenborg were presented as precursors of Mesmer.15↤ 15 Morning Herald 15 Feb. 1786. Mainaduc also recruited twenty women to form a “Hygeian Society,” which was incorporated with a sister lodge in France. To demonstrate their Masonic notions of equality, Mainaduc instructed Chastanier to round up twenty poor patients for free treatment at Bloomsbury. Over the next decade, Mainaduc instructed over 270 paying customers in the secret science. Among the dozen identifiable Swedenborgians were four artistic peers of Blake—Maria and Richard Cosway, P. J. de Loutherbourg, and William Sharp.

In Mainaduc’s lectures, printed posthumously in 1798 with his portrait by Cosway, there are many striking similarities to terms and themes in Blake’s work. In April 1786, Mainaduc revealed to an eager assembly that men and women “possess a power in themselves of which they are ignorant, and want but little instruction to do more than they are aware of; I open to you an astonishing field, if you dare to cultivate it, a field which must redouble the religionist’s devotion, confirm the deist in the existence of his God, and fill the atheist with astonishment.”16↤ 16 Mainaduc xi. His first lecture covered “Atmospheres and Emanations of the Form,” which proved that “emanating atoms continually fly from the earth, and from all its productions; and that, as the earth, so all its forms are surrounded by atmospheres, and passed through by emanations peculiar to themselves.”17↤ 17 Mainaduc 28-29. The “atmospherical part of the human body” may, by the magnetizer’s effort, “be attracted from, or distended to, any unlimited distance”; it may then “penetrate any other form in nature.” The healing occurs when through “the influence of Volition (or Spirit)” the Emanations are “forced out of their natural course” or “attracted into the Pores of the Operator.”18↤ 18 Mainaduc 81-83. The magnetizer is effective according to the Intention and Energy of his or her “spiritual Volition.” Mainaduc then gave detailed instructions, such as: ↤ 19 Mainaduc 97.

The Examiner should fix on some particular part of the Patient’s external or internal Form; then, turning the backs of his hands, with the fingers a little bent, he must vigorously and steadily command the Emanations and Atmospheres, which derive from that part, to strike his Hands, and must closely attend to whatever Impressions are produced on them.19Maria Cosway possessed great “spiritual Volition” and was easily magnetized. As she wrote her lover, Thomas Jefferson, “I am susceptible and everything that surrounds me has great power to magnetise me.”20↤ 20 Julian Boyd, ed., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, 22 vols. (Princeton UP, 1950) 4: 3-4; F. M. Brodie, Thomas Jefferson (New York, 1974) 204-24.

Mainaduc and Chastanier soon faced stiff competition as new rivals entered the field. In France the Puysegur brothers rediscovered “induced hypnosis” or “magnetic sleep,” in which the entranced patient spoke with spirits and displayed clairvoyance. In a derivation of the Cabalistic “revolution of perspective,” the somnambulists saw the inner organs of their patients in externalized visions.21↤ 21 Gershom Scholem, Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism (New York: Schocken Books, 1954) 217. Mainaduc complained that this “new food” of somnambulism is “grasped at with avidity by impostors” and many “entertain their acquaintances with the wonder of their last comatose dream.”22↤ 22 Mainaduc 196. Even worse, “a most scientific lass, wishing me to believe she saw my brain,” said it “resembled an oyster.” Cosway and Sharp magnetized Henry Tresham (another friend of Blake) and told him he had a hole in his liver, “the form of which Cosway drew.”23↤ 23 K. Garlick and A. Macintyre, eds., The Diary of Joseph Farington, 16 vols. (New Haven: Yale UP, 1978) 3: 710. Blake probably refers to this magnetic effect when he proclaims: “Their eyes their ears nostrils & tongues roll outward they behold / What is within now seen without” (E 314). Moreover, Blake’s strange descriptions of Bowlahoola and Allamanda seem to draw on the magnetizers’ concept of the Archaeus, the ganglion of sympathetic nerves in the abdominal region.

Paracelsus and Van Helmont believed the Archaeus to be “a sort of demon presiding over the stomach, acting constantly by means of vital spirits, performing the most important offices in the animal economy, producing all the organic changes which take place within the corporeal frame.”24↤ 24 J. C. Colquhoun, trans., Report of the Experiments on Animal Magnetism (Edinburgh: Robert Cadell, 1833) 101-03. Van Helmont further claimed that by virtue of the Archaeus, man could be approximated to the realm of spirits. In somnambulistic trance, the “exalted sensibility” of the epigastric region transferred perception from the brain to the abdomen (including the erotically susceptible “loins”). The modern magnetizer manipulated the transfer of sensibility from one organ to another, in order to clear the flow of lucidity (health) from obstruction (disease). Mainaduc taught that “in Man is comprised in miniature, the entire vegetating system in its greatest perfection.”25↤ 25 Mainaduc 31. His form is composed of pipes and particles, “between which the begin page 22 | ↑ back to top most extensive and minute porosity admits . . . the passage of atoms and fluids.” Similarly, though with vivid mythic overtones, Blake describes “the Four States of Humanity in its Repose”:

The First State is in the Head, the Second is in the Heart:Blake’s principal regions of vision are Bowlahoola, “the Stomach in every individual man,” and Allamanda, “the Loins & Seminal Vessels” (E 121, 134). His strange physiology was entirely consistent with that of animal magnetism, especially in its Swedenborgian forms.

The Third in the Loins & Seminal Vessels & the Fourth

In the Stomach & Intestines terrible, deadly, unutterable

And he whose Gates are opend in those Regions of his Body

Can from those Gates view all these wondrous Imaginations

(E 134)

Where Mainaduc and his more radical disciples got into trouble was in their technique of stroking the Archaeus: ↤ 26 Mainaduc 207.

The fluids are to be conducted upward, slowly, softly, and gently . . . [in order to] carry up the fluids from the stomach to the brain . . . the operation is to commence at the pit of the stomach, and the first intention must be to separate the plexus, or heap of nerves, situated in that part . . . The nerves must then be pursued, through the diaphragm up the pleura, and into the skull to the Brain.26Critics charged them with sexual designs on the women; in fact, this accusation was the real motive for the French Commission’s hostile report. In an unpublished appendix, sent secretly to the French king, the commissioners revealed: ↤ 27 “Animal Magnetism,” British and Foreign Medical Review 14 (1839): 9.

. . . the greater number of women who are magnetised are not really ill . . . their senses are not impaired, their youth has all its sensibility. Continued proximity, contact, the communication of bodily warmth, and the mingling of glances . . . effect a communication of sensations and affections. The man who magnetises had generally the knees of his female patient enclosed between his own . . . the hand is applied to the hypochondriac region, and sometimes over the ovaries. Touch is exercised over a large extent of surface, and in the neighborhood of the most sensitive parts of the body . . . the reciprocal attraction of the sexes acts, of course, with all its force. . . . When this state of crisis approaches, the visage fires by degrees, and the eyes light up with desire . . . the eyelids now become moist; the breathing hurried and irregular; the bosom heaves violently and rapidly, and convulsions and sudden twitchings take place in particular limbs, and sometimes all over the body. In lively and sensitive women, the last stage, the most agreeable termination of their emotions, is often a convulsion.27One critic saw “a woman thrown by a magnetic process into a furor uterinus,” and London wits ridiculed Maria Cosway and the high-born women who flocked to Mainaduc as Princesses of the “House of Libidinowsky.”28↤ 28 “Animal Magnetism” 19; A Letter to a Physician in the Country on Animal Magnetism (London: J. Debrett, 1786) 32.

Undeterred by such criticism and inspired by visions into their patients’ Bowlahoola and Allamanda, Cosway, Sharp, and Loutherbourg enthusiastically practiced magnetic medicine. At Loutherbourg’s house in Hammersmith, thousands of patients sought the miracle cure. As Anthony Pasquin wickedly remarked, “The blind followed the whoopings of the lame” to the “liberal chymists” of the clinic.29↤ 29 Anthony Pasquin [John Williams], Memoirs of the Royal Academicians (London: H. D. Symonds, 1796) 80-81. Initially with Mainaduc’s approval, Chastanier opened a magnetic clinic in his residence at 62 Tottenham Court Road, where the Swedenborgian Freemasons also gathered.30↤ 30 Morning Post 16 June 1786. But Chastanier eventually broke with Mainaduc, charging that he “made the art instrumental to horrid enormities.”31↤ 31 Monthly Observer and New Church Record 1 (Jan.-Dec. 1857): 420. Apparently worried by the competition of his own pupils, Mainaduc began to require a Masonic-style oath of secrecy from his clients.32↤ 32 Mainaduc xi. For paying “Brothers,” he would draw aside the veil of the sacred mysteries: “Here we shall find the grand arcanum, the steady point d’appui, the philosopher’s stone, and omnium uno”—all under the Masonic “all-seeing Eye of the Creator.”33↤ 33 Mainaduc 226-28.

Blake probably could not have afforded Mainaduc’s deluxe course, but he may have benefited from Chastanier’s inexpensive instruction. Blake may also have attended the spin-off lectures of Thomas Holloway, the engraver, with whom he worked on Lavater’s Essay on Physiognomy. (Lavater himself was an enthusiastic magnetist.34↤ 34 Analytical Review 6 (1790): 155-56. ) Following the lead of his brother John, Thomas Holloway gave lectures on animal magnetism which attracted hundreds of artisans as well as professional people.35↤ 35 World 2 Oct. 1791; Thomas Holloway, Memoir (London, 1827) 29-32. The Holloways’ magnetic therapy was so successful that John Newton tried to persuade the poet William Cowper to accept their offer of treatment. However, a wary Cowper replied: ↤ 36 J. King and C. Ryskamp, eds., The Letters and Prose Writings of William Cowper, 5 vols. (Oxford: Clarendon, 1979-82) 3: 404-05.

With respect to my own initiation into the Secret of Animal Magnetism, I have a thousand doubts. Twice, as you know, I have been overwhelmed with the blackest despair, and at those times every thing in which I have been at any period of my life concerned has afforded to the Enemy a handle against me. I tremble therefore almost at every step I take, lest on some future similar occasion, it should yield him opportunity and furnish him with means to torment me. Decide for me, if you can. And, in the mean time, . . . best thanks to Mr. Holloway for his most obliging offer. I am perhaps the only man living who would hesitate a moment whether on such easy terms he should, or should not accept it. But if he finds another like me, he will make a greater discovery than even that which he has already made of the principles of this wonderful art.36Cowper’s worry was later echoed by Blake, who resented those magnetic healers who tried to bind “all Mental Powers by Diseases,” rather than allowing the artist to “spend his soul in Prophecy.”37↤ 37 David V. Erdman, The Notebook of William Blake (Oxford: Clarendon, 1973) N50-51.

As part of their sympathy for the French Revolution and the new egalitarian trends, the Holloways developed a simplified, democratic form of magnetism.38↤ 38 Holloway, Memoir 24-25; Maria, The Secret Revealed: or, Animal Magnetism Displayed (London: T. Hawkins, 1790) 5-11. Though they were both Freemasons and enjoined secrecy on their pupils, they required neither oath nor bond.39↤ 39 Grand Lodge, London: Atholl Register F., vol. 6, f.487; Index to Moderns, F series, vol. 14. Teaching a short, simplified form of hypnosis and making no supernatural claims, the Holloways avoided the illuminist controversies that eventually placed animal magnetism on dangerous political grounds. John Holloway was still advertising his lectures in 1805, opposite the Shakespeare Gallery.

begin page 23 | ↑ back to top begin page 24 | ↑ back to topFor many of Mainaduc’s students, however, magnetism became increasingly a vehicle for political radicalism. Darnton points out that as the French Revolution developed, “mesmerists tended increasingly to neglect the sick in order to decipher hieroglyphics, manipulate magic numbers, communicate with spirits, and listen to speeches on Egyptian religion.”40↤ 40 Darnton 70. This development stemmed from the somnambulists’ refined techniques of vision-inducement as well as a revival of Cabalistic meditation on Hebrew letters and talismans. The magnetizing Swedenborgians in London were soon linked with Cabalistic developments in France, for they were visited by three celebrated gurus of Cabalistic Freemasonry—Count Grabianka of the Avignon Illuminés, “Count” Cagliostro of the Egyptian Rite, and Louis Claude de Saint-Martin of the Elus Coens.41↤ 41 Garrett, Respectable 100-20; Constantin Photiades, Count Cagliostro (London: William Rider, 1932); M. Matter, Saint-Martin (Paris, 1862). Their colorful personalities and visionary claims made a lasting impression on the London group, while at the same time accelerating the turbulent schisms over political and sexual controversies.

As the English government geared up for a counterrevolutionary crackdown on secret societies, followers of Swedenborg and Mainaduc were considered fair game for official spies and police. On 4 March 1795, the London Times charged that Swedenborg was “the Chief of the Somnambulists,” whose influence on the “revolutionarily exalted” prophets prepared the public mind for “great political convulsions.” In 1797 the Abbé Barruel (a former Freemason, now an emigré priest) proclaimed in London: ↤ 42 Augustin Barruel, Memoirs, Illustrating the History of Jacobinism, 4 vols. (London: T. Burton, 1797-98) 4: 546.

The brethren of Avignon recognized the Illuminés of Swedenborg as their parent Sect; neither were they unmindful of the embassy sent them by the Lodge of Hampstead. Under the auspices of De Mainaduc, the have seen their disciples thirsting after that celestial Jerusalem, that purifying fire (for these are the expressions I have heard them make use of) that was to kindle into general conflagration throughout the earth by means of the French Revolution—and thus Jacobin Equality and Liberty was to be universally triumphant in the streets of London.42

Unintimidated by the crackdown and encouraged by his Swedenborgian readers, the flamboyant William Belcher published Intellectual Electricity, Novum Organum of Vision, and Grand Mystic System . . . the Connection between the Material and Spiritual World Elucidated, the Medium of Thought Rendered Visible, Instinct Seems Advancing to Intuition, Politics Assume a Form of Magical Intimation (London, 1798). Boldly interpreting mystical vision and sexual passion in electromagnetic terms, Belcher praised the illuminati as the only society still practcing “this field of science.”43↤ 43 William Belcher, Intellectual Electricity (London, 1798) i, 27. To political radicals like Cosway, who acquired Belcher’s work, his assertion that “mysticism carried Buonaparte into Egypt, its original school,” must have rung with millenarial implications.44↤ 44 Belcher (i); handlist of half the books in Cosway’s library, compiled by the late Diana Wilson and now at the Huntington Library. I am grateful to Morton D. Paley for informing me about this list. Among the Swedenborgian and Masonic acquaintances of Cosway and Blake, political charge and countercharge proliferated, as increasingly polarized radicals and conservatives split into rival factions. However, the lines were not always clearly drawn, and radical devotées of animal magnetism were sometimes odd bedfellows of political conservatives.

Into this complex milieu in 1793-94 walked George Baldwin, who eagerly plunged into magnetic experiments regardless of their political ramifications.45↤ 45 “George Baldwin,” Dictionary of National Biography. Home on leave from his post as British Consul in Egypt, Baldwin renewed his acquaintance with various artists and Swedenborgians. Blake may already have known Baldwin in the period 1781-86, when the exotic traveler and his beautiful Greek wife, Jane, attracted much attention in London’s social scene. Cosway and Bartolozzi painted portraits of Mrs. Baldwin, and Joshua Reynolds exhibited “The Fair Greek,” in full Turkish costume, at the Royal Academy in 1782.46↤ 46 Freeman O’Donoghue, Catalogue of Engraved British Portraits . . . in the British Museum (London, 1910) 1: 107; J. T. H. Baily, Francesco Bartolozzi (London, 1907). Baldwin also shared Blake’s interest in Druid lore, Ossian, Boehme, Law, and Paracelsus.47↤ 47 George Baldwin, Mr. Baldwin’s Legacy to His Daughter (London: William Bulmer, 1811) 4: 40-45. During his adventures in the Middle East, Baldwin had investigated the contacts between Egypt and India, which he applied to the study of hieroglyphics.48↤ 48 British Museum Additional Manuscripts. 29,198.f.379. These inquiries also fueled his interest in native medicines, with their heavy component of magic and trance. While in London, he read in The Gazeteer and New Daily Advertiser (6 October 1783) an article on Quinquet’s “new discoveries in the electric arcana.”49↤ 49 George Baldwin, An Investigation into Principles (London: George Bulmer, 1801) 31. He studied the French Commission Report on magnetism in 1784 and interpreted its hostile criticism as testimony to “the stupendous power” of magnetism.50↤ 50 Baldwin, Legacy iv.

Fired with enthusiasm for electric and magnetic therapy, Baldwin returned to Egypt in December 1786, where he ordered a continuing stream of literature on animal magnetism. One of these may have been Lavater’s Essays on Physiognomy (London, 1789), with engravings by Blake and Holloway, for a “Captain Baldwin” subscribed to the first volume. As noted earlier, Lavater was widely viewed as a fanatic for animal magnetism, and his system of physiognomy was assimilated into the grab-bag of magnetic literature.51↤ 51 Darnton passim. By 1789 Baldwin was tirelessly experimenting with magnetic therapy and even boasted of finding an effective preventative for the plague. Believing the disease traveled by “electric sparks,” he advocated the coating of the body with sweet oils to prevent penetration of the pores.52↤ 52 George Baldwin, Political Recollections Relative to Egypt, 2nd. rev. ed. (London: W. Bulmer, 1802) 127.

In 1793-94 Baldwin returned to London, where he showed off his collection of drawings of Eastern scenes.53↤ 53 Dawson 672. He probably revisited Cosway and his artistic friends, as well as those Swedenborgians who still experimented with magnetic and electric cures. Baldwin subscribed to George Adams’ Lectures on Natural and Experimental Philosophy (London, 1794), which combined Swedenborgianism and Freemasonry with advanced magnetic and electric theory. Blake almost certainly knew Adams, who was also the mentor of Blake’s friend, Dr. John Birch. (Blake would later praise “Mr. Birch’s Electrical begin page 25 | ↑ back to top Magic” for relieving his wife’s rheumatism [E 759].) George Adams embodied the contradictory strains among the Swedenborgians, for he was fascinated by occult and magnetic phenomenon but repelled by the radical politics which often accompanied its practice. Baldwin shared these polarized opinions but, like Adams in the 1790s, he was willing to keep his feet in both camps in the interest of the “new science.”

While he was in London, Baldwin apparently added somnambulistic techniques to his magnetic repertoire, for on his return to Egypt in late 1794, he plunged into experiments in spirit-communication, automatic writing, and dream analysis. Could he have learned these from Blake, Cosway, Loutherbourg, Sharp, and their Swedenborgian friends? In 1794 Blake described his own involvement in spirit-dictation:

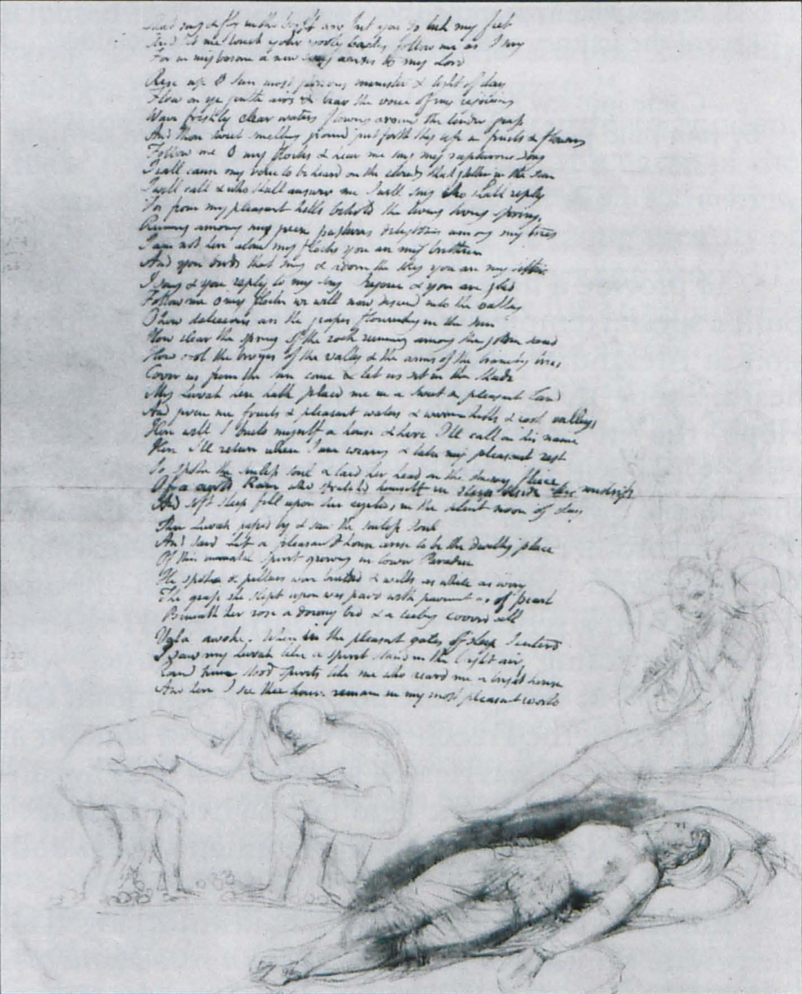

Eternals I hear your call gladly,In Vala, which he began in 1795, Blake describes various magnetic phenomenon: “ . . . they behold / What is within now seen without”; Los has “sparks issuing from his hair”; emanations produce “sweet rapturd trance” (E 314, 332, 371). Most suggestive, though, of Blake’s probable collaboration with Baldwin is the drawing in Night Nine of a woman dressed in Turkish costume, holding a tambourine, lying in a trance state on Oriental pillows.54↤ 54 C. T. Magno and D. V. Erdman, The Four Zoas by William Blake (Bucknell UP, 1987) 242. In the earlier portraits of Mrs. Baldwin by Cosway and Reynolds, she holds a tambourine and sits on a divan, respectively. George Baldwin also dressed in Oriental garb in London and discoursed on magnetism while lolling on pillows.55↤ 55 Thomas Wright, Life of William Blake, 2 vols. (London: Olney, Bucks, 1929) 2: 31. The accompanying speech by Vala seems to echo Baldwin’s new enthusiasm for the “magnetic sleep” which led to spirit-communication: ↤ 56 Magno and Erdman 242.

Dictate swift winged words, & fear not

To unfold your dark visions of torment.

(E 70)

Vala awoke. “When in the pleasant gates of sleep I enter’d,

“I saw my Luvah like a spirit stand in the bright air.

“Round him stood spirits like me . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

he laid his hand on my head,

“And when he laid his hand upon me, from the gates of sleep I came.”56

In Egypt from 1794 to 1798, Baldwin continued his experiments with the “magnetic sleep,” which he explained as “the discovery of a spiritual influence on the physical temperature of man.”57↤ 57 Baldwin, Investigations 88. As he witnessed many “elevations of the soul,” Baldwin became convinced that “no earthly bound could bound this spirit.” Then, in January 1795, his life changed dramatically when a wandering Italian poet, Casare Avena de Valdieri, arrived in Alexandria and joined in Baldwin’s sessions. Through the poet’s magnetic trance, Baldwin achieved communication with the spirit of a young girl, his first love in the 1760s. He rapturously affirmed:

It is in common tradition over the world, that spirits will come and converse with men; mankind, in general, hath an involuntary dread of these spirits; why?—for my part I see nothing to dread; or something of the kind must exist to justify our fears.—I say indeed that these spirits do exist;—must of necessity exist . . . 58Baldwin and Valdieri magnetized an Arab servant, whose clairvoyant descriptions were verified by witnesses. But the most astounding of their feats was the massive output of poetry and operas produced by Valdieri from spirit-dictation. In a trance state, Valdieri claimed to travel through the celestial world, speak with spirits, and experience a state of ecstatic beatitude. The poetic works, produced by automatic writing, revealed “amid the most eccentric flights of fancy, an order, an intricacy of arrangement, a regular confusion, a wilderness of beauties, an harmony of verse, a reach of discovery that shall satisfy his (the reader’s) mind about the real author of it.”59↤ 59 Baldwin, Investigations 93. Like Blake in Milton, Baldwin identified this dictating spirit as the same Muse who illumined Milton in Paradise Lost, 1.25. For Baldwin, Blake’s description of automatic writing would seem precisely accurate: begin page 26 | ↑ back to top

. . . Muses who inspire the Poet’s Song,

Record the journey of immortal Milton thro’ your Realms

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . Come into my hand

By your mild power; descending down the Nerves of my right arm

From out the Portals of my Brain . . .

(E 96)

To provide a haven for the writing bouts, Baldwin built a special temple within the British consulary mansion in Alexandria. Baldwin’s artistic friends may have heard about these psychic adventures from Thomas Hope, the art patron, who returned to London after visiting Baldwin in 1797.60↤ 60 Dawson 427. Hope was also interested in the Cabala, Swedenborgianism, and magnetism; moreover, his brother Henry was a student of Mainaduc.61↤ 61 Sandor Baumgarten, Le Crépuscule Neo-Classique: Thomas Hope (Paris: Didier, 1958) 218-24, 254; also Mainaduc xii. When Napoleon moved into Egypt, Baldwin opposed the French in a series of complex intrigues. He had to flee Egypt, losing all his property, but returned with British forces in 1801, where he played a significant role in the defeat of the French. Arriving back in London in late 1801, Baldwin was treated as a political hero by conservatives and as a psychic hero by magnetizers. Blake’s allusion to Baldwin suggests his familiarity with both roles.

Immediately upon his arrival, Baldwin arranged for the private printing of An Investigation into Principles (1801). It was not for sale but was distributed by the author to his friends. The work traced the history of animal magnetism and told the romantic story of his contact with the spirit of his lost love. Evidently encouraged by his friends, he next printed privately La Prima Musa Clio (1802), which included his explanation of automatic writing and the Italian poems of Valdieri. Though Blake was in Felpham, he may have heard of these works from London friends or from Hayley, who was an inveterate student of electric and magnetic medicine.62↤ 62 Morchard Bishop, Blake’s Hayley (London: Gollancz, 1951) 95-96. When Blake returned to London in autumn 1803, he evidently joined the magnetic sessions of Baldwin, Cosway, and their friends. Baldwin soon gained a devoted following. As Thomas Wright observed, Baldwin was “in respect to the healing art, the Aloysius Horn of his day; he was now famous and lolled on Oriental cushions amid strange hangings.”63↤ 63 Wright, Blake 2: 31.

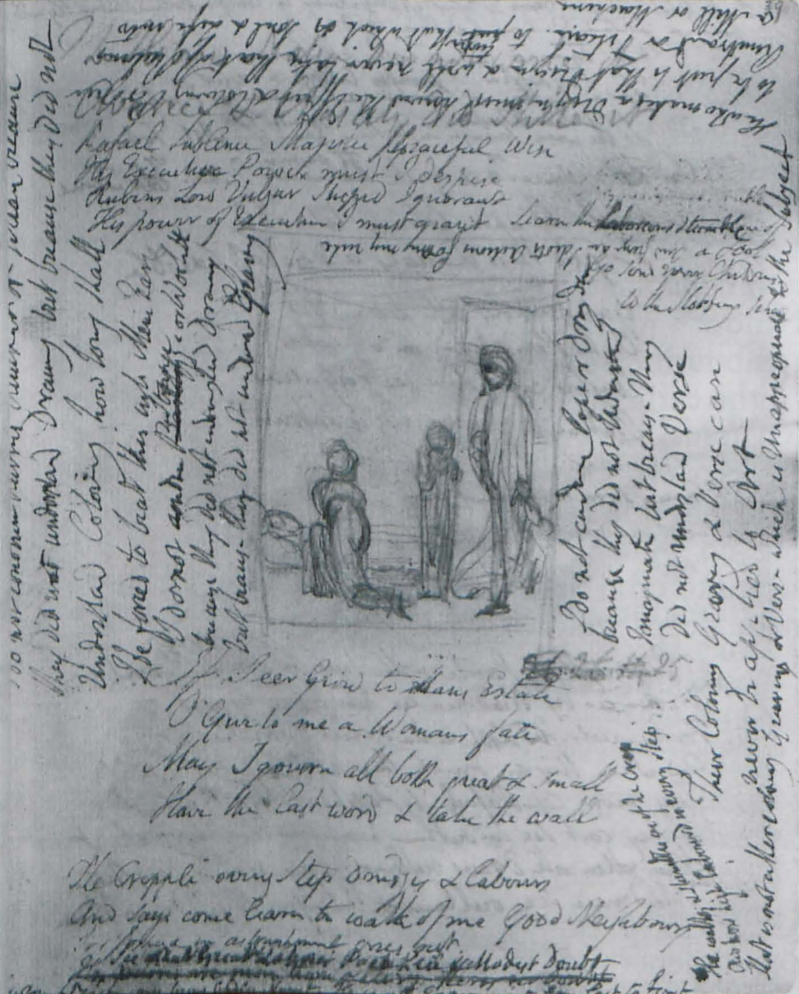

Baldwin’s courageous commitment to his visionary studies would surely have appealed to Blake. In Mr. Baldwin’s Legacy to His Daughter, or the Divinity of Truth (1811), he revealed his enthusiastic philosophy which merged Paracelsus, Van Helmont, Swedenborg, and Druidism into a therapeutic, visionary science. He had delayed publication of this work because “I have been told, that I shall be called a Visionary”; however, “I am told by Scripture that where there is no vision the people perish.”64↤ 64 Baldwin, Legacy iii. In B. A.’s Book of Dreams (London, 1813), he described his treatment of an extremely deformed young lady (B. A.), who not only saw visions but greatly improved physically. Blake seems to refer directly to this case in his Notebook, emblem 19, when he sketches a sick girl on a pallet, approached by a turbaned, cloaked man. Blake’s odd lines may reflect his ambivalent feelings towards Baldwin: “The Cripple every step Drudges & labours / And says come learn to walk of me Good Neighbours.”65↤ 65 Erdman, Notebook N39. The next lines scratched out and confused, either condemn the single vision (“doubt”) of Newton, Bacon, and Reynolds, or possibly scorn the medical treatment of Baldwin: “He is all Experiments from last to first.” On the same page where Blake criticizes “Cosway, Frazer, and Baldwin,” for merely healing the sick, he shows five figures grouped in pyramidal form (suggestive of Egypt), who watch over the sickbed of a girl who holds a book (possibly B. A.’s Book of Dreams).66↤ 66 Erdman, Notebook N39.

Blake’s identification of Baldwin with “Egypt’s Lake” may point to one reason for their broken friendship. Blake, whose acquittal of treason charges did not mean he gave up his radicalism, was possibly put off by Baldwin’s contribution to Napoleon’s defeat in Egypt. In 1802 Baldwin published Political Recollections Relative to Egypt, in which he revealed that it was his idea to cut the canal of Alexandria and let sea water into the dry bed of Lake Mareotis. When carried out by Sir Sydney Smith on 13 April 1801, the French were cut off from all communication with the interior of Egypt. This led to the English victory over Napoleon in August. Baldwin carried home “the famous Standard of the Invincible Legion of Bonaparte,” and he was caught up in the out-burst of patriotic enthusiasm.67↤ 67 Baldwin, Political Recollections 145. Thus, Blake’s phrase, “Baldwin of Egypt’s Lake,” had definite political connotations. Cosway, on the other hand, seemed to forgive Baldwin his political stance while benefitting from his magnetic expertise. Still as radical as Blake, Cosway could blithely boast of witnessing the King’s birthday dinner (while invisible and “in a spiritual capacity”) and then rejoice exceedingly at the victories of Bonaparte.68↤ 68 Garlick and Macintyre, Diary 7: 3096.

The last four lines of Blake’s poem suggest another possible reason for Baldwin’s withdrawal from Blake. Blake accuses Hayley, Flaxman, and Stothard of prudish concern over his works. Certainly, if Baldwin saw Blake’s Vala and believed that Mrs. Baldwin was portrayed in Oriental costume, he may have been offended. Through her diaphanous Turkish veil, her vulva is clearly revealed. For the Swedenborgian magnetizers of the 1790s, the mystical significance of the female genitals to the visionary process was considered the highest of “coelestial arcana.”69↤ 69 Based on Swedenborg’s descriptions in his Journal of Dreams, Spiritual Diary, and Conjugial Love (especially #103, 146). See also Magno and Erdman 158. William Belcher proclaimed, “As well almost might Paracelsus make a man, without female aid, as can be acquired mystic knowledge without woman, the centre of magnetic attraction.”70↤ 70 Belcher, Intellectual 109. Ebenezer Sibly, a Swedenborgian Freemason and magnetizer, made a series of Rosicrucian drawings which depicted the vulva as the center of the Cabalistic universe.71↤ 71 Ebenezer Sibly, The Dumb Made to Speak . . . or the Grand Arcanum of Adepts. Manuscript #4594 in Wellcome Institute of History of Medicine.

The radical Swedenborgians among the magnetizers struggled to publish Swedenborg’s more explicit writings on the methodology of the Cabalistic erotic trance, but their efforts were frustrated by a wave of counter-revolutionary prudery which developed at the turn of the century. By 1805, Fuseli complained about prudish objections to naked figures in art, and Thomas Hope feared that nude sculpture might have to be draped for exhibition.72↤ 72 Garlick and Macintyre, Diary 7: 2518-19. In this new pre-Victorian climate, the radical magnetizers went underground. The explicit Cabalistic drawings of Sibly and manuscripts of erotic rituals were never published; rather, they became the provenance of a secretive Rosicrucian network that gathered at occult bookstores and clandestine lodges in the early decades of the century.73↤ 73 Sibly, Dumb; A Catalogue of Books and Manuscripts . . . on Astrology, Magic, and Alchymy, etc. . . . the Stock of John Denley (London, 1820). Cosway and Blake participated in this network, whose members stimulated a revival of Hebrew and Cabalistic studies, especially among a new generation of magnetizers.74↤ 74 Schuchard, Freemasonry 476-505; and more extensively in Men of Desire.

Bindman observes that on his return to London, “Blake’s rejection of the Classics is in the name of the Hebraic sublime.”75↤ 75 David Bindman, Blake as an Artist (Oxford: Phaidon, 1977) 141. n his renewed devotion to Hebrew studies, there may be a clue to the puzzling identity of “Frazer,” the third member of Blake’s healing trio. A “J” or “I” Frazer appears on Mainaduc’s list of pupils. He may be the artist, G. Fraser, who painted a striking portrait of Solomon Bennett, a talented Jewish engraver.76↤ 76 Alfred Rubens, “Early Anglo-Jewish Artists,” Transactions of Jewish Historical Society of England 14 (1935-39): 112-17. The initials to names on Mainaduc’s list are often inaccurate. Keynes speculated that Blake referred to Alexander Fraser, a minor painter (Blake: Complete Writings, ed. Geoffrey Keynes [Oxford UP, 1985] 911). But Fraser lived in Edinburgh until 1813, when he moved to London. Earlier, I speculated that Blake referred to Alexander Fraser, a Freemason and shorthand writer, who was also a friend of Bennett (Schuchard, Freemasonry 478-80). The question remains open. Though nothing more is currently known of G. Fraser, the fact that Cosway was a patron of Bennett makes the possible linkage of Blake to Bennett (via Frazer and Cosway) worth pursuing. The question of Blake’s access to Hebrew and Cabalistic instruction, through published sources or personal contacts, continues to perplex scholars.77↤ 77 Sheila Spector, “Kabbalistic Sources—Blake’s and his Critics’,” Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly 17 (1983-84): 84-99. Though the full context of Swedenborgian and Masonic connections with Jews in London needs extensive investigation, the immediate context of magnetism in 1804-11 makes Solomon Bennett a plausible candidate for a role in Blake’s biography. Besides being an admirable artist and erudite man of letters, Bennett was the most accomplished Hebrew teacher in London. Moreover, the connection between magnetic healers and Jewish instructors is consistent with the experiences of Cosway and Baldwin among the Swedenborgians and students of Mainaduc. Dr. Isaac Benamore, a Jewish physician, was Mainaduc’s most successful disciple.78↤ 78 Rainsford Papers, British Museum Add. Mss. 23,670,f.71; Monthly Observer and New Church Record 3 (Jan.-Dec. 1859): 281. Benamore’s son was also a physician and student of Mainaduc. Benamore was still practicing magnetic medicine, in collaboration with various Swedenborgians, in 1807. Curiously, though William Cowper turned down the Holloway’s offer of magnetic therapy, he had only praise for Benamore’s treatment of a friend.79↤ 79 Cowper, Letters 3: 404.

If Blake knew Solomon Bennett, through the medium of Cosway, Frazer, and their magnetizing friends, the two would have had much in common, as well as critical differences of religious opinion. Bennett (1761-1831) came from a Polish family in White Russia and seemed to have absorbed the peculiar, paradoxical mentality of the Sabbatian Jews of the period.80↤ 80 Arthur Barnett, “Solomon Bennett, 1761-1838: Artist, Hebraist, and Controversialist,” Transactions of Jewish Historical Society of England 17 (1951-52): 91-111. In his home area, many Jews became Freemasons and aspired to assimilation with Christians. Bennett recorded “the unbounded veneration I feel for our present Nazarenes . . . from my infancy I was their admirer, and exerted myself to be their imitator.”81↤ 81 Solomon Bennett, The Constancy of Israel, 2nd. ed. (London: printed for the author and sold by him at No. 475, Strand, 1812) iv-v. In 1792 Bennett set out for Copenhagen, determined to pursue a career in the arts that was impossible at home. He evidently had some contact with the alchemical circle headed by Prince Charles of Hesse-Cassel, who attempted to unite Christians and Jews in a new Masonic rite of “Asiatic Brethren,” which synthesized Sabbatian Cabalism and Christian mysticism.82↤ 82 Jacob Katz, Jews and Freemasons in Europe (Harvard UP, 1970) 27-53. It was in this Danish lodge that Blake’s idol Lavater, a veteran begin page 28 | ↑ back to top magnetizer, achieved the visionary spirit-communication that made him a convinced Rosicrucian.83↤ 83 Antoine Faivre, Mystiques, Théosophes et Illuminés au Siècle des Lumières (New York: Georg Olms, 1976) 175-90. Fuseli owned Lavater’s Reise nach Copenhagen and was working on a biography of his friend in the early 1800s.

As Scholem observes, the “Asiatic Brethren” occupied a “no man’s land” between extreme tendencies of rationalism and mysticism, which it aspired to synthesize in a Christian-Cabalistic equilibrium.84↤ 84 Gershom Scholem, Du frankisme au jacobinisme (Paris: Gallimard, 1981) 28. Bennett exemplified this paradoxical mentality, for he was a skeptical, scientific rationalist, who also studied Cabala and alchemy. His strikingly engraved portrait of Lorenz Werskoss, a seventeenth-century alchemist, was said to reflect “his own mystic nature.”85↤ 85 S. Kirchstein, Juedische Graphiker (Berlin, 1918) 20. Bennett was elected to the Danish Royal Academy of Art, a singular honor for a Jew at the time. Moving to Berlin in 1795, Bennett achieved acclaim as a portraitist and evidently mixed in high Jewish-Masonic circles.86↤ 86 Katz 27-53; Bennett, Constancy 224-25. However, he chafed under Prussian anti-Semitism and, seeking a freer climate, he emigrated to London in November 1799.

Relishing English liberties, Bennett boldly expressed his eclectic and colorful views, compounded of radical free-thinking and ardent spirituality. Soon rejected as a heretic by orthodox rabbis, whom he scorned as “insignificant reptiles,” he found supporters among gentile artists, literary men, and Freemasons.87↤ 87 Bennett, Constancy 216. While studying voraciously, he eked out a living by engraving and giving Hebrew lessons. William Beechey, who helped Blake in 1805, also helped Bennett that year, by allowing the poverty-stricken Jew to engrave his portrait of the Prince of Wales (Grand Master of the Freemasons).88↤ 88 G. E. Bentley, Jr., Blake Records (Oxford: Clarendon, 1969) 165; Rubens, “Anglo-Jewish” 114. Bennett’s portrait of Shakespeare was used as the frontispiece to the 1807 Stockdale edition of Shakespeare’s Dramatic Works (the edition used by Coleridge for his marginalia).89↤ 89 Bentley 17; British Museum Catalogue entry for Stockdale edition. In 1808 Bennett boldly exhibited his own portrait of his hero, Napoleon, whom he praised in millenarial terms for emancipating the Jews and spreading tolerance throughout Europe.90↤ 90 Barnett 96; Bennett, Constancy 5, 228.

Bennett may have met Cosway and Frazer by this time, for they evidently supported his effort to publish The Constancy of Israel (1809), by “a native of Poland . . . professing the Arts in London.” Bennett stressed his appreciation for the artists who helped him publish, and Cosway owned the extremely rare first edition of the work.91↤ 91 Handlist of Cosway’s library. The frontispiece was Bennett’s engraving of his portrait by Fraser. As Kirchstein observes, Fraser’s portrayal reveals the whole history of Bennett: “In the eyes are a penetrating spirituality and a quiet pensive melancholy. You can read from his face all his wanderings and striving, all his intellectual and artistic powers, all his lone battle with life.”92↤ 92 Barnett 94. Bennett’s book was a learned defense of Judaism in the face of aggressive propaganda by the newly formed London Society for the Conversion of the Jews. Bennett heard in some chapels, “a crow from the pulpit, with a human voice,” who ignorantly attacked Jewish beliefs, and he scorned the “religious barterers” who “spy among the poor, illiterate, and distressed” Jews of Petticoat-lane and Frying-pan Alley.93↤ 93 Bennett, Constancy 34, 206. Cosway, who had long been a champion of the Jews, followed the conversionist controversy with interest and collected many of the treatises put forth by both radical and reactionary “philo-Semites.”94↤ 94 Handlist of Cosway’s library.

Though Bennett welcomed Christian students and enjoyed debating with sincere readers of the Hebrew Bible, he resented those conversionist efforts that were based on ignorant linguistic analysis and anachronistic Christological interpretations. It may have been Cosway who was the “friend” who showed Bennett An Address to the Jews (1710), by John Xeres.95↤ 95 Bennett, Constancy 34, 206. Cosway owned a rare copy of the little known work, which described Xeres’ reasons for abandoning Judaism and embracing Christianity. Bennett then refuted Xeres’ argument that the Cabalists’ notion of a plurality within God was the same as the Christians’ Trinity.96↤ 96 Bennett, Constancy 105-06. Blake, who was immersed in Hebrew studies and mystical illustrations of the Old Testament, made his own contribution to the conversionist controversy with his address “To the Jews” in Jerusalem. As Bogan notes, in Blake’s solution, “Hebrew Adam / English Albion joins the two seemingly disparate nations of England and Israel in a common patriarchal religion.”97↤ 97 E 171; J. M. Bogan, “Apocalypse Now: William Blake and the Conversion of the Jews,” English Language Notes 19 (1981): 117. Even more suggestive of Blake’s conversionist preoccupation with the Jewish visionary tradition is the frontispiece to Jerusalem, in which the illuminator, Los, is dressed like a Hasidic rabbi or Polish Jew.98↤ 98 See entry on “William Blake” in Encyclopedia Judaica.

Cosway, Frazer, and their magnetizing friends may have sought out Bennett because of his expertise in Cabala, for the Jewish mystical traditions of the microcosmic Grand Man underlay the psychic physiology of animal magnetism. Bennett described his studies in published and manuscript works on “Kabala or Magic, which are merely extracts from the Hebrew.”99↤ 99 Bennett, Constancy 200. He discusses the Cabalists’ seven names for Alohim, but then urges that we must “proceed to a more sublime idea of this noble creation of the Microcosm,” for Man’s “qualities material and spiritual” are the “sublime of all Creations.”100↤ 100 Bennett, Constancy 106-09. In Blake’s address “To the Jews,” he stresses this Cabalistic concept: “You have a tradition, that Man anciently containd in his mighty limbs all things in Heaven & Earth” (E 171). Unlike Blake, Cosway, and Baldwin, however, Bennett was determined to maintain a scientific and rational view of the Cabalistic microcosm. He scorned the revivers of occult notions of spirits: ↤ 101 Bennett, Constancy 77.

The prophane doctrines of invisible beings who act on mankind, faith in sorcerers, visionaries, dreamers, etc. which had been but too successful on the human mind are now exploded, except in the brains of some chimerical individuals, or hypocrites, to dazzle the lowest class of humanity.101

For Blake, who was enthusiastically describing in Milton his celestial journeys among the Rosicrucian-style “Fairies, Nymphs, Gnomes, and Genii of the Four Elements,” Bennett’s scorn would have stung. Moreover, begin page 29 | ↑ back to top Blake’s defense of a “Professor of Sidereal Science” (an astrologer), who was arrested and “the cabalistical chattels of his profession” confiscated, would undoubtedly have been ridiculed by Bennett as the product of a low-class, chimerical brain.102↤ 102 E 769; “Police . . . Astrology,” Oracle and True Briton (13 Oct. 1807). Cosway, however, may have understood Bennett’s desire to distance himself in print from spirit-communicators and magnetizers. Cosway acquired The Supernatural Magazine (Dublin, 1809), in which a critic charged that animal magnetism was a diabolical, anti-Christian practice, imported from France, which had insidious links with the naturalization of the Jews and the Revolution.103↤ 103 The Supernatural Magazine (Dublin, 1809) 7-9. The same magazine noted that a recent book described the current revival of Rosicrucianism in London, out of the ashes of Egyptian Masonry, Illuminism, and the New Jerusalem Church.104↤ 104 The Supernatural Magazine 67-71. Bennett may have become disillusioned with those of his Masonic friends whose interest in Cabalism led them into Rosicrucianism, for, as the radical republican Richard Carlile later charged, “the drift . . . of these Rosicrucian degrees, is to make Masonry begin in Judaism and end in Christianity.”105↤ 105 Richard Carlile, ed., The Republican, 12 (1825): 469. Bennett became the close friend of the Duke of Sussex, who, as Grand Master from 1813 on, struggled to maintain Jewish rights within Freemasonry and to suppress the exclusively Christian Rosicrucian degrees. Certainly, Blake seemed to share that “drift,” for he challenged the Jews that “If your tradition that Man contained in his Limbs, all Animals, is True,” then you should “Take up the Cross O Israel, & follow Jesus” (E 174).

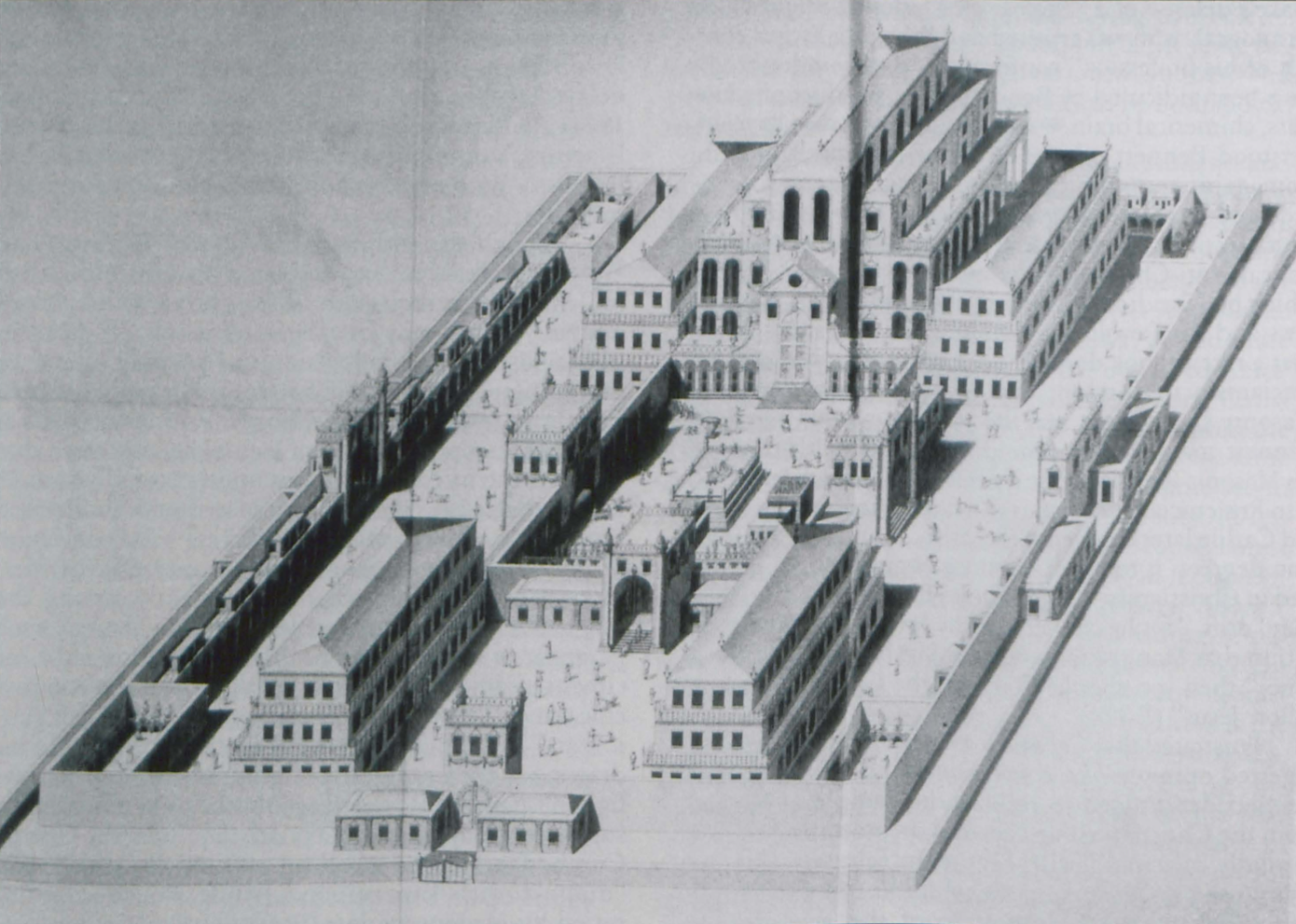

Frustrated that Cabalism was being turned into “ill digested opinions” by conversionists and Rosicrucians, Bennett determined to reclaim the Temple of Ezekiel from the Christian visionaries and dreamers and to root it solidly in actual Jewish history. In February 1811, he announced a new work on the rebuilding of the Temple of Ezekiel, with an explanation of the Jews’ “newly reformed democratical or rather theocratical government”: ↤ 106 Solomon Bennett, The Temple of Ezekiel (London, 1824) 151.

Although the explanation of the visionary Temple of Ezekiel upon scientific principles may be objectionable to some orthodox Jews or Christians, who prefer the mystical to the rational, especially in scriptural matters, yet I think . . . the prophets (independently of their divine inspiration) were able politicians and men of science.106Bennett had prepared for the work a large, fold-out engraving of the Temple of Ezekiel which was considered a “masterpiece of imagination and technique,” showing his “sound knowledge of architectural draftsmanship.”107↤ 107 Barnett 96. It is possible that Blake’s preoccupation with the architectural design of Ezekiel’s Temple in Jerusalem was stimulated by conversations or arguments with Bennett.108↤ 108 See Morton D. Paley, “‘Wonderful Originals’—Blake and Ancient Sculpture,” in Blake in His Time, eds. R. N. Essick and D. Pearce (Indiana UP, 1978) 183-92. Told by a Christian printer that “It is our duty to suppress everything relating to Hebrew literature,” Bennett turned to his artistic and Masonic friends for help.109↤ 109 Bennett, Temple 5. Three current friends or patrons of Blake—William Frend, Prince Hoare, and Earl Spencer—subscribed to the project.110↤ 110 Bentley 273, 136, 232. Another subscriber, the sculptor John Henning, utilized Bennett’s Hebrew instruction to further his own investigations into alchemy, astrology, and geomancy (studies Henning shared with John Varley, soon to become Blake’s intimate friend).111↤ 111 William Bell Scott, Autobiographical Notes, 2 vols. (New York: Harper’s, 1892) 1:115-20. Unfortunately, orthodox opposition (both Jewish and Christian) delayed publication of The Temple of Ezekiel until 1824. As Blake became more vociferous in his British Israelism, Bennett became more vehement in his Jewish Israelism. Both men became isolated in their own communities.

Though the withdrawal of Cosway, Baldwin, and Frazer from Blake may have also signaled the withdrawal of Bennett from their circle, Blake’s break with his magnetizing friends may have been temporary. In fact, his suspicious and hostile reaction was possibly caused by overindulgence in Cabalistic-magnetic experiments. Cabalistic texts and Swedenborg’s writings are full of warnings about the dangers of mental derangement that threaten the intense meditator upon magical arcana.112↤ 112 Sheila Spector, Jewish Mysticism (New York: Garland, 1984) xi; Swedenborg’s Journal of Dreams and Spiritual Diary passim. Podmore discusses the paranoia that often accompanied excessive attempts at magnetic trances.113↤ 113 Frank Podmore, From Mesmer to Christian Science (New York: University Books, 1963) 258. The conviction of persecution by distant enemies, operating by Mesmerism or telepathy, occurred frequently among the magnetizers of the nineteenth century. Though such paranoia is one of “the commonest delusions of incipient insanity,” many sane persons who dabble in psychic trances “have not escaped the contagion of this panic fear.” In 1806 Blake accused Stothard of effacing his drawing of the Canterbury Pilgrims by means of a “malignant spell.”114↤ 114 Bentley 180. He railed against the plots of his steady supporters Hayley and Flaxman. The tolerant George Cumberland noted that he seemed “crack’d” and “dimm’d with superstition,” while Robert Southey pitied his obvious madness.115↤ 115 Bentley 229, 236. Curiously, Seymour Kirkup also diagnosed Blake as insane, a verdict Kirkup later retracted when he became an animal magnetizer.116↤ 116 W. M. Rossetti, Rossetti Papers (London, 1903) 171-72. Bentley points out that between 1807 and 1812, Blake seemed to lose his firm grasp of the nature and limits of reality: ↤ 117 Bentley 180.

He sometimes seems to have thought of the spiritual world as supplanting rather than supplementing the ordinary world of causality. More and more frequently the spirits seem to have been controlling Blake rather than merely advising him.117

Blake’s insistence that animal magnetism include exorcism—“he casts out devils”—may have smacked of magical megalomania to his friends. However, his plight would have been well understood by Benedict Chastanier, the former “powerful assistant” to Mainaduc. After playing a lead role in disseminating animal magnetism, Chastanier “at last found out its evil tendency, and like an honest man first abandoned the practice and next exposed it.”118↤ 118 William Spence, Essays in Divinity and Physic (London: Robert Hindmarsh, 1792) 58. Still friendly with Cosway in the early 1800s, Chastanier may have influenced Cosway’s withdrawal from Blake’s essentially magical practice.119↤ 119 Rainsford Papers, British Museum Add. Mss. 23, 670, vol. 2.f.275. As Chastanier explained in 1795, animal magnetism was begin page 30 | ↑ back to top

. . . the very great danger there is for a man to meddle with any Science that openeth to them a freer communication with the world of Spirits, than that they naturally are to have; for as every man is by nature attached to his own peculiar evil, (and there is no Man, nor even any Angel, also free from evil,) the Spirits with whom he may thus communicate, can but confirm him more and more into that evil, peculiarly annexed to his own nature, and thus become an insur-mountable bar to his Regeneration.120

Despite the timidity or genuine worry of his magnetizing friends, Blake was committed to his “perilous adventure,” regardless of political, erotic, or psychic dangers. Though he would be driven to note, “Janry. 20. 1807 between Two & Seven in the Evening—Despair,” he could also boast in happier times, “excuse my enthusiasm or rather madness, for I am really drunk with intellectual vision” (E 733, 694, 757).