minute particular

A Twist in the Tale of “The Tyger”

Most readers of “The Tyger” have their own ideas of its meaning: I shall not be adding my own interpretation, but merely offering a factual record of minute particulars, by pointing to a number of verbal parallels with Erasmus Darwin’s The Botanic Garden. A few of these were given in my book Erasmus Darwin and the Romantic Poets; the others I have come across more recently.

Darwin’s poem The Botanic Garden was published in two parts, with Part 2, The Loves of the Plants, appearing first in 1789, and Part 1, The Economy of Vegetation, nominally in 1791, though it did not actually appear until about June 1792, probably because of delay in printing Blake’s superb engravings of the Portland Vase.1↤ 1 Desmond King-Hele, ed. The Letters of Erasmus Darwin (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1981) 215. After my quotations I give the canto and line numbers from the third edition of The Loves of the Plants (1791) and the first edition of The Economy of Vegetation.

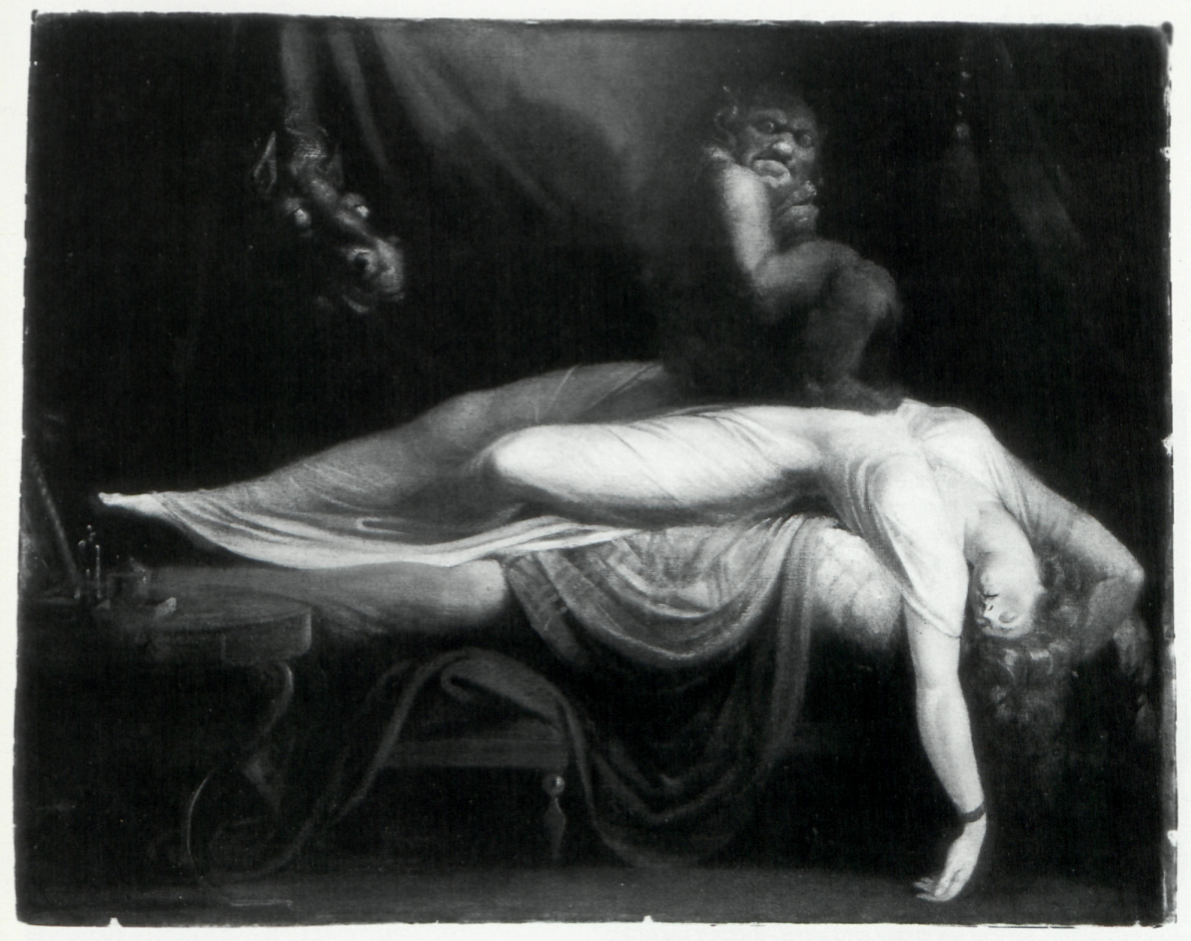

One of the best-known passages in Darwin’s poem was his vivid description of a nightmare, based on Fuseli’s painting (illus. 1), which features the half-visible head of a large animal with unnaturally bright eyes, enveloped in black night. Obviously the head is intended as that of a horse, but the word “nightmare” has no etymological connection with horses, male or female.2↤ 2 N. Powell, Fuseli: The Nightmare (London: Allen Lane, 1973). (The nightmare is produced by the incubus, or “squab fiend” as Darwin calls him.) Could Fuseli’s monstrous animal, with eyes burning bright in the blackness of the night, have given Blake the cue for his Tyger? Such a speculation is encouraged by a verbal parallel between “The Tyger” and Darwin’s verses about the sleeping girl. The nightmare induces in her an “interrupted heartpulse” and “suffocative breath”, as frightful thoughts

In dread succession agonize her mind.This is not quite “What dread hand? and what dread feet?,” but dread is powerfully present, “in her hands, and . . . in her feet”; and “dread” was a favorite adjective with Darwin, used twenty times in The Botanic Garden.

O’er her fair limbs convulsive tremors fleet,

Start in her hands, and struggle in her feet.

(Lov. Pl. 3: 68-70)

The burning brightness of the first two stanzas of “The Tyger” has some resemblances to Darwin’s picture of Nebuchadnezzar ordering “a vast pyre . . . of sulphurous coal and pitch-exuding pine” with “huge bellows” to fan the roaring flames: begin page 105 | ↑ back to top

Bright and more bright the blazing deluge flows,Nebuchadnezzar was so dreadfully surprised because Shadrec, Meshec, and Abednego were enduring the heat of the furnace unscathed: “Fierce flames innocuous, as they step, retire; / And calm they move amid a world of fire!” (Lov. Pl. 4: 69-70). In these two quotations we have burning once and bright twice, as well as dread and four other obvious words from “The Tyger”—furnace, deep, eyes and fire. Also Darwin has a complete answer to Blake’s question “What the hand dare seize the fire?”

And white with sevenfold heat the furnace glows.

And now the Monarch fix’d with dread surprize

Deep in the burning valut his dazzled eyes.

(Lov. Pl. 4: 61-64)

There is another curious parallel in Darwin’s picture of the night-flowering Cerea, who lifts her brows “to the skies” at midnight, “Eyes the white zenith; counts the suns, that roll / Their distant fires, and blaze around the Pole” (Lov. Pl. 4: 21-22). Blake sets “the fire of thine eyes” deep in “distant . . . skies”: the image is similar, begin page 106 | ↑ back to top though the Tyger is very different from the strange plant that flowers unseen.

In an earlier canto of The Loves of the Plants there is a correctly-ordered preview of Blake’s word-sequence “deeps . . . on . . . wings . . . aspire . . . fire”: Darwin

Calls up with magic voice the shapes that sleepDarwin likes the “aspire/fire” rhyme and uses it in The Botanic Garden on three other occasions (Lov. Pl. 1: 281-82; Ec. Veg. 1: 225-26 and 1: 255-56).

In Earth’s dark bosom, or unfathom’d deep;

That shrin’d in air on viewless wings aspire,

Or blazing bathe in elemental fire.

(Lov. Pl. 2: 297-300)

After all these parallels you may think it is easy to find a parallel for anything. But that is not so: unlike conventional literary criticism, which can sweep unwanted facts under the carpet, source-hunting is sharp and scientific—failures cannot be hidden. Thus there is no “fearful symmetry” to be found anywhere in the verse of The Botanic Garden. Also Darwin never mentions a Tyger specifically in his poem. The nearest he comes to it is with his fierce-eyed “Monster of the Nile”: “With Tyger-paw He prints the brineless strand . . . / Rolls his fierce eye-balls, clasps his iron claws” (Ec. Veg. 4: 434, 437). Nor does Darwin offer a “forest of the night”: his closest approach is when Hercules “drives the Lion to his dusky cave” in “Nemea’s howling forests” (Ec. Veg. 1: 313).

No labor of Hercules is needed, however, to find parallels in canto 1 of The Economy of Vegetation, because its subject is Fire. Darwin tells us how Vulcan and Cyclops “forged immortal arms” on “thundering anvils”; when Venus came to watch them she “Admired their sinewy arms, and shoulders bare, / And ponderous hammers lifted high in air” (Ec. Veg. 1: 169-70). Blake has shoulder, sinews, hammer and anvil, though his immortal artificer is forging not fearsome weapons but a fearsome Tyger. Darwin is equally creative at times, for example in bringing to birth the Tyger-pawed Monster of the Nile:

First in translucent lymph with cobweb-threadsThe first two lines answer Blake’s “In what furnace was thy brain?” In the last line Darwin’s phrase “The red Heart dances” is too pretty for Blake, who soberly states “thy heart began to beat”; in Urizen, however, closer links with Darwin’s picture can be found.3↤ 3 See D. C. Leonard, “Erasmus Darwin and William Blake,” Eighteenth Century Life 4 (1978): 79-81.

The Brain’s fine floating tissue swells, and spreads;

Nerve after nerve the glistening spine descends,

The red Heart dances, the Aorta bends.

(Ec. Veg. 4: 425-28)

There are many other parallels from canto 1 of The Economy of Vegetation. For example, lines 216-22 have “dread Destroyer . . . bright . . . dread snakes . . . immortal . . . Terror.” The noun chain appears thirteen times in The Botanic Garden, notably in the picture of a shackled “Giant-form” bursting his chains to bring about the French Revolution, an image that may have links with Blake’s French Revolution.4↤ 4 See D. Worrall, “William Blake and Erasmus Darwin’s Botanic Garden,” Bulletin of New York Public Library, 78 (1975): 397-417. However, the phrase “what the chain?” does not appear in The Botanic Garden. Nor do Blake’s “deadly terrors”: the best Darwin can offer is “twisted terror” (Ec. Veg. 3: 502), with “sinewy shoulders” in the previous line, to parallel “shoulder . . . twist . . . sinews . . . terrors” in the third and fourth stanzas of “The Tyger.”

That brings me to the fifth stanza of “The Tyger,” which I have already discussed at some length in my book,5↤ 5 See Desmond King-Hele, Erasmus Darwin and the Romantic Poets (London: Macmillan Press, 1986) 49-50. where I quoted from Darwin’s long note on the aurora, to show that it might be a source for “the stars threw down their spears.” I also gave a quotation from Darwin’s Zoonomia, with his evolutionary explanation—now sanctioned by modern science—of how the tyger was created from the same original “living filament” as the lamb. Thus he answers Blake’s question in stanza 5, and the query in stanza 1 about the framer of the Tyger’s fearful symmetry. Darwin’s answer was timely too, for volume 1 of Zoonomia was published in 1794, the same year as Songs of Experience.

Perhaps I have been twisting the tail of the Tyger too sadistically; but a full scholarly appreciation of Blake’s poem should take account of all such verbal parallels. There is much evidence6↤ 6 Worrall 397-417; N. Hilton, “The Spectre of Darwin,” rev. of The Botanic Garden, by Erasmus Darwin, Blake 15 (1981) 36-48; King-Hele, Romantic Poets, chap. 2. that Blake was influenced by Darwin between 1789 and 1795, so the parallels may well be significant.