article

begin page 64 | ↑ back to topThe Good (In Spite of What You May Have Heard) Samaritan

Commentators on Blake’s illustrations insist that through them Blake modifies and criticizes the poets he illustrates, and it is often clear that they are right. But sometimes the expectation of finding such criticism can be a cause of error—the antithetical meaning is given a premature welcome before an adequate search has been made for a more fully articulated reading of the design. I think I have such a fuller reading of one of Blake’s illustrations for Young’s Night Thoughts, which has recently received renewed critical attention. In this essay, I shall maintain that the design is indeed critical of Young, but in a way quite different from that described by previous commentary. My interpretation of the relationship between Blake’s design and Young’s text is based first on a close reading of the design itself in relation to the biblical text from which it originates, and then on a consideration of the relationship between the completed design and the particular portion of the text of Young’s poem which it illustrates.

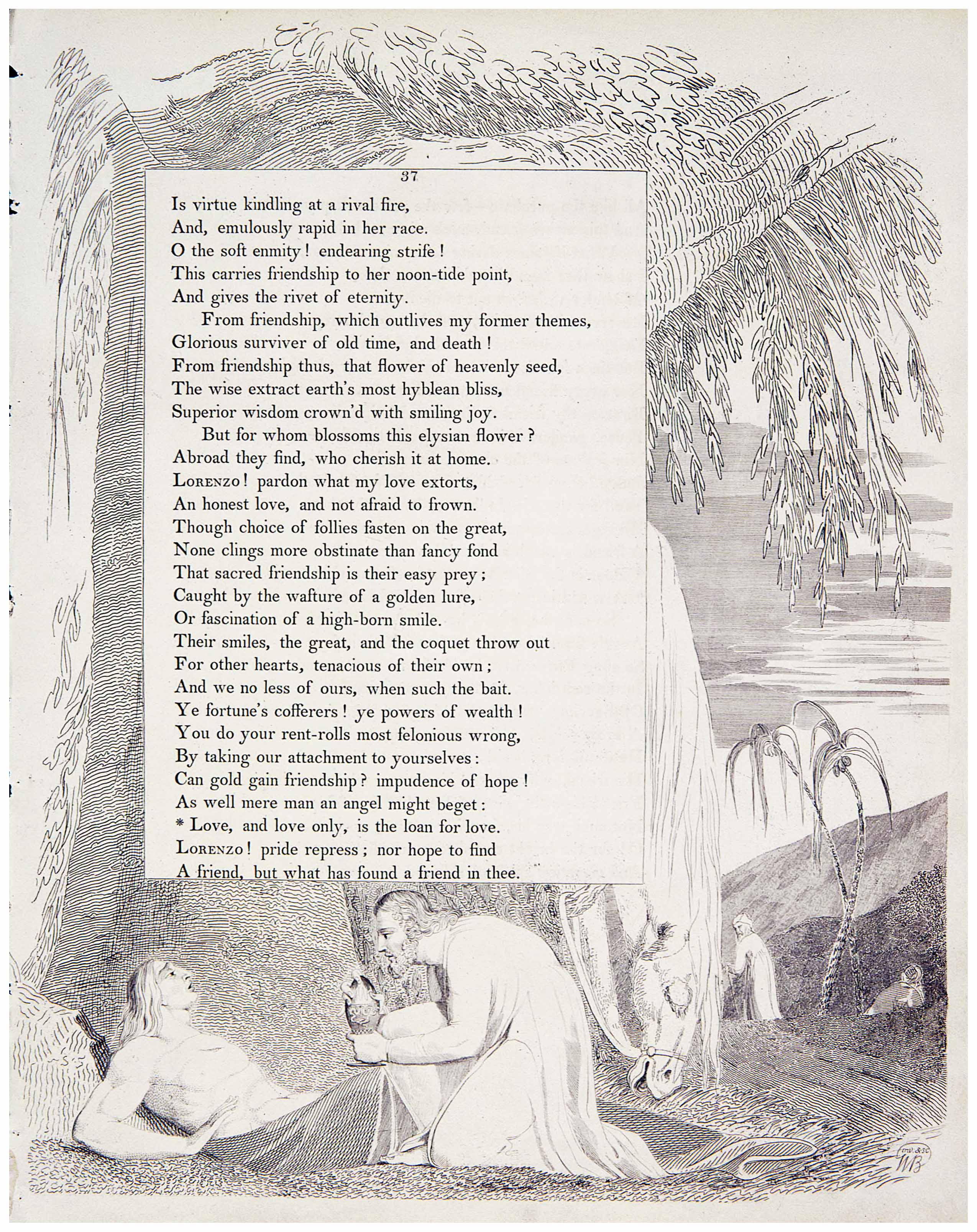

In their very useful edition of Night Thoughts, Robert Essick and Jenijoy La Belle give both the “Explanation of the Engravings” bound into some copies of Edward’s edition and a commentary of their own. The “Explanation” of the design on p. 37 (illus. 1) reads as follows: “The story of the good Samaritan, introduced by the artist as an illustration of the poet’s sentiment, that love alone and kind offices can purchase love.”1↤ 1 Robert Essick and Jenijoy La Belle, eds., Night Thoughts or The Complaint and The Consolation, illustrated by William Blake (New York: Dover, 1975) xi. The explicator, whom Gilchrist identified as Fuseli, though that attribution has often been questioned, reads the design as illustrating the text quite straightforwardly, paraphrasing the very line starred by Blake in the text that he used for his original water color drawing, which reads: “Love, and love only, is the loan for love.”2↤ 2 Essick and La Belle, Night Thoughts 37. The star was retained in the etched version, as is the case in most of the designs, so we cannot draw any conclusions about the identity of the explicator from that fact—he may or may not have had access to Blake’s original water color design.

The editorial commentary by Essick and La Belle that follows focuses on the difficulty of interpreting the cup offered by the Samaritan, which bears a serpent motif on its side. The editors write:

Not only does the serpent represent mortality throughout Blake’s Night Thoughts designs, but the cup and serpent motif is also a traditional emblem for St. John the Evangelist. The Emperor Domitian once tried to kill St. John with a cup of poisoned wine, but a serpent sprang from the cup as a miraculous warning to the intended victim. Thus the prone figure in this illustration would be quite justified in shunning, as he seems to do with his hand gesture, the offer of an ostensibly poisonous gift. The difficulties in reconciling the disparate allusions in the design are almost as great as recognizing true friendship.This offers an explanation, but with a full recognition of the interpretive difficulties. It also identifies two key images of uncertain meaning, the serpent on the vessel, and the victim’s gesture of apparent rejection.

Discussion of this image resumes with the recent publication of John E. Grant’s essay “Jesus and the Powers That Be in Blake’s Designs for Young’s Night Thoughts.”3↤ 3 John E. Grant, “Jesus and the Powers That Be in Blake’s Designs for Young’s Night Thoughts” in Blake and His Bibles, ed. David V. Erdman (West Cornwall, CT.: Locust Hill Press, 1990) 77-79. The numbers in Grant’s text and my own refer to the numbers assigned to the water color designs in William Blake’s Designs for Edward Young’s “Night Thoughts,” ed. John E. Grant, Edward J. Rose, and Michael Tolley, with the assistance of David V. Erdman (Oxford: Clarendon P, 1980), 2 vols. His comments are framed within an argument about Blake’s overall response to Young’s text, which he sees—and I am in full agreement here—as including “a wide range of sympathies and dissympathies” (73). Grant holds that Blake refocuses Young’s God the father as Jesus the brother of man, and that Blake, in the course of “ingeniously” (77) finding ways of introducing the figure of Jesus where it is not explicitly demanded by Young’s text, shows Jesus as a figure who gathers power as the illustrations to the poem progress (83-84).

After the frontispiece to Volume One, which does not illustrate any specific text, the first “indubitable depiction of Jesus” (77) is as the Good Samaritan of NT 68, which was then etched as p. 37 of Edward’s edition. Grant notes that traditional interpretation allowed for an identification of the Good Samaritan as a form or image of Jesus himself, which can be confirmed by turning to a variety of commentators. Matthew Henry, for instance, the most popular of English commentators,4↤ 4 T. H. Darlow and H. F. Moule, revised A. S. Herbert, Historical Catalogue of The English Bible 1525-1961 (London: British and Foreign Bible Society, 1968) 241. Henry’s work went through many editions. writes: “We were like this poor distressed traveller. The law of Moses passes by on the other side, as having neither pity nor power to help us; but then comes the blessed Jesus, that good Samaritan; he has compassion on us.”5↤ 5 Matthew Henry, Commentary on the Whole Bible, ed. Rev. Leslie F. Church (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan Publishing House, 1971) 1449 (commentary on Luke 10.25-37). John Gill, in referring to the Samaritan, says succinctly “By whom Christ may be meant. . . .”6↤ 6 John Gill, An Exposition of the New Testament, new ed., 5 vols. (London, 1774) 2: 143. Gill is not recorded by Darlow and Moule, presumably because he does not provide a complete text to accompany his commentary, but DNB records that the first edition was published in 1746-48, so the work was evidently popular enough to justify the new edition, and adds that he used “his extensive rabbinical learning,” as will appear in later references to his commentary. I confess an arbitrary element in my choice of commentators—I have made no attempt to canvas the whole vast field. But both Henry and Gill are interesting, both were evidently quite widely read, the two argue from somewhat different positions, and so separately and together they provide useful evidence about widely received interpretation at the time. The interpretation was evidently commonplace, though one should note that the identification of the Good Samaritan as Jesus adds to it without in any way undoing his continuing identity as the Good Samaritan.

In spite of his acceptance of this identification, however, Grant goes on to build a case for a rather negative view of the action depicted in the design, pointing to some of the features that troubled Essick and La Belle, and questioning whether the scene can represent “an unmixed blessing.” begin page 65 | ↑ back to top He refers to the disturbing snake, and also to the horse on which the Samaritan has arrived, suggesting that the latter is derived from the “donkey included among the ominous familiars of the subterranean goddess ‘Hecate’ . . .” (77). Grant then looks at the interaction between the two human figures in the drama, and finds disturbing implications there too:

The startled appearance of Jesus in the watercolor version constitutes a clear sign that he had been unprepared for rejection by the Jewish victim. . . . Such details indicate that Blake wished to introduce doubts as to whether this Good Samaritan could have succeeded as a benefactor or ‘Friend of All Mankind.’ (E 524)[e]

Grant’s comments on the etched version modify this view just a little, suggesting that the signs of consternation have been removed from the face of Jesus: “now Jesus is represented as being masterfully composed and earnest as he proffers his cure” (79). But his view of the general sense of the scene is unchanged, and is still focused on the serpent, “the ominous but still perfectly apparent presence depicted on the cup” (79).7↤ 7 Because Grant’s view of the basic thrust of the design does not change when he turns to the etched version, I have illustrated only the etched version, which reproduces better than the water color. The differences are very small, and neither Grant’s overall interpretation of the design nor my own depends on an exact reading of the expression on the face of Jesus. Grant’s overall view is summed up in this passage: “ . . . the posture of Jesus crouched beneath the text panel, holding unopened the sinister decorated cup, repelled by the victim he wishes to help, marks (at this stage) his inability to accomplish his mission” (83-84).

Grant has taken the doubts expressed by Essick and La Belle and has turned them into assertions that aim to show Blake separating his perspective from Young’s by a progressive revelation of the power of Jesus, which at this early stage of Blake’s visual commentary has not yet achieved a full statement. Grant’s point would seem to be that this version of the Good Samaritan shows a kind of embryonic Jesus, not yet capable of powerful action against resistance, and offering possibly poisonous gifts (the contents of the chalice are called “a dubious potion” in the text below his Figure 1).

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

The interpretive strategies proposed by Essick and La Belle, and developed by Grant, are based initially on a negative reading of the image of the serpent. But any reading of the serpent must first consider the nature of the representation of that serpent; the negative interpretations of it seem based on assumptions about what would be appropriate responses to the representation of a real, living animal. Terror and horror are therefore read as the responses of the victim. But we are actually dealing with the representation of a representation of a serpent; in both the original drawing and the etching there is a clearly visible line separating the body of the flask or chalice from what appears to be the cover, which has a different texture. The serpent is incised or enamelled on the main body of the vessel. Terror and horror would be merely misplaced superstition; we, and the victim, are dealing with an image, not an animal, and that image must therefore be interpreted symbolically, as the representation of a meaning.

begin page 66 | ↑ back to topThe point deserves elaboration. Essick and La Belle refer to the story of St. John the Evangelist. This is without much doubt the foundation of the description of Fidelia in the house of Holiness in Book 1 of Spenser’s The Faerie Queene, which at first sight might appear to offer a good analogy with the design under consideration: ↤ 8 Edmund Spenser, The Faerie Queene, ed. A. C. Hamilton (London: Longman, 1977) 1.10.13.

She was araied all in lilly white,Hamilton’s note on this passage tells us that “St. John the Evangelist is usually represented with a chalice out of which issues a serpent. . . . The Golden Legend records the familiar story of how John drank a cup of poison to prove his faith.” That story only makes sense, however, if we understand this serpent to be alive and capable of a mortal bite, so that to overcome the fear of such a death is a true indication of faith. The reflexive “did himselfe enfold” makes clear that Spenser’s serpent is very much alive. The apparent analogy between the story of St. John and Blake’s design is not in fact substantial or useful.

And in her right hand bore a cup of gold,

With wine and water fild vp to the hight,

In which a Serpent did himselfe enfold,

That horrour made to all, that did behold. . . .8

There is another traditional interpretation of the image of the serpent, however, of which Hamilton reminds us. His note identifies it as also “the emblem of Aesculapius, the symbol of healing; also of the crucified Christ, the symbol of redemption. The serpent lifted up by Moses (Num. 21.9) is interpreted typologically as Christ lifted up on the cross (John 3.14).” This can be put more forcefully by suggesting that the story of Aesculapius can easily be read as a type of the story of Jesus, as is strongly suggested by Sandy’s version of Ocyroë’s prophecy over the infant Aesculapius: ↤ 9 George Sandys, Ovid’s Metamorphosis,[e] ed. Karl K. Hulley and Stanley T. Vandersall (Lincoln: U of Nebraska P, 1970) 97.

Health-giver to the World, grow infant, grow;For some reason, Sandys misses this opportunity in his commentary, but he redeems himself in his comment on the long account of the removal of Aesculapius to Rome in the fifteenth book: “For the Serpent was sacred unto him; not onely . . . for the quicknesse of his sight. . . . But because so restorative and soveraigne in Physicke; and therefore deservedly the Character of health. So the Brasen Serpent, the type of our aeternall health, erected by Moses, cured those who beheld it” (714). In a more straightforward vein, Lemprière writes of Aesculapius that “Serpents are more particularly sacred to him, not only as the ancient physicians used them in their prescriptions; but because they were the symbols of prudence and foresight, so necessary in the medical profession.”10↤ 10 Lemprière, Classical Dictionary, 3rd ed. [1797] ed. F. A. Wright (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1984) 19. These mythographical comments, from sources that Blake almost certainly knew,11↤ 11 It is evident that Blake knew his Ovid, but I do not remember seeing it remarked before that his spelling “Ovids Metamorphosis” (E 556) points, though not definitively, to Sandys, who seems to have been the last to spell the title in that way. It seems that Keats was not the only major romantic poet to appreciate Sandys. Many other sources comment on the serpent as the attribute of Aesculapius—e.g. Joseph Spence, Polymetis (London 1747) 132. provide us with a reading of the serpent image on the chalice offered by the Samaritan which is much more relevant and appropriate to the present context, and lead us to consider further the implications of identifying the Samaritan as both Jesus and Aesculapius.

To whom mortalitie so much shall owe.

Fled Soules thou shalt restore to their aboads:

And once again the pleasure of the Gods.

To doe the like, thy Grand-sires [Jupiter] flames denie:

And thou, begotten by a God, must die.

Thou, of a bloodless corps, a God shalt be:

And Nature twice shall be renew’d in thee.9

The explicitly medical nature of the Samaritan’s intervention is sometimes overlooked, but not by eighteenth-century commentators. Henry notes that the Samaritan “did the surgeon’s part, for want of a better.” Gill gives a more heavily allegorized interpretation: the wounds of the victim represent “the morbid and diseased condition that sin has brought man into,” which are “incurable by any, but the great physician of souls, the Lord Jesus Christ.”12↤ 12 Henry, Commentary 1448; Gill, Exposition 2: 142. In the context of this offering of medical help by a figure whose face is clearly modeled on that of Jesus, it would seem reasonable to interpret the serpent-decorated chalice as an emblem of both Aesculapius, the god of healing and medicine whose conventional attribute was the serpent or the caduceus, and of Jesus, the true healer whom Blake has made visible within the body of the Samaritan, who is also associated with the symbol of the serpent, and with a chalice filled with healing liquids. Blake is implying that any act of helping and healing would be the act of a true Christian. Aesculapius is, in effect, one of the incarnations of Jesus, as is the Good Samaritan himself, or, to put it a little differently, the Good Samaritan is an incarnation of Jesus as Aesculapius, the power to heal.

There is evidence in Blake’s writing to support this reading of the figure. In A Descriptive Catalogue, Blake describes the Doctor of Physic as “the first of his profession; perfect, learned, completely Master and Doctor in his art,” and then identifies him as “the Esculapius,” one of the “eternal Principles that exist in all ages” (E 536). One might remember also that “Jesus & his Apostles & Disciples were all Artists,” and that “A Poet a Painter a Musician an Architect: the Man / Or Woman who is not one of these is not a Christian” (“The Laocoön,” E 274). As Milton explains, these archetypal arts become “apparent in Time & Space, in the Three Professions / Poetry in Religion: Music, Law: Painting, in Physic & Surgery” (M 27: 59-60, E 125). The true physician is both artist and Christian. I wish to emphasize, however, that Blake is not directly illustrating his own myth, but rather that his myth and the basis of the design under consideration are both derived by a process of transformation from public materials, and that any interpretation of the design must proceed by working through those materials in the forms in which they were available to Blake.

We need now to consider further the contents that we are to assume fill the flask or chalice. The right hand of the begin page 67 | ↑ back to top Samaritan appears to be about to lift the lid of the vessel; presumably it contains the “oil and wine” referred to in the Gospel account, which the Samaritan poured in as he “bound up his [the victim’s] wounds.” The two liquids were conventionally understood as antiseptic (wine) and healing balm (oil),13↤ 13 Henry, Commentary 1448. The distinction of functions is based on the text of the Bible: Cruden notes the frequency with which wine is used as a metaphor for the anger of God, and the ways in which oil is associated with “comfort and refreshment.” which, as John Wesley explains, “when well beaten together, are one of the best balsams that can be applied to a fresh wound.”14↤ 14 John Wesley, Explanatory Notes upon The New Testament (London: Charles H. Kelly, n.d.) 241. Gill gives more detailed evidence from Jewish commentary, together with a more typologically oriented explanation that bridges the gap between Aesculapius and Jesus: “by oil may be meant, the grace of the Spirit of God . . .: and by wine, the doctrines of the Gospel. . . .”15↤ 15 Gill, Exposition 2: 144. The invisible but strongly implied contents of the vessel in Blake’s design can thus be read as a conventional healing mixture, which in its literal form is as appropriate to Aesculapius as it is appropriate to Jesus when typologically understood. Both the serpent and the oil and wine presumed to fill the flask function to identify the Samaritan as simultaneously Jesus and Aesculapius.

The expression on the victim’s face, and the gesture performed by his hands, can now be more easily interpreted. Henry’s commentary is again useful in focusing for us a sometimes neglected aspect of the story: the victim “was succoured and relieved by a stranger, a certain Samaritan, of that nation which of all others the Jews most despised and detested and would have no dealings with.”16↤ 16 Henry, Commentary 1448. Gill makes a very similar statement, Exposition 2: 143. Henry’s statement is based on such texts as Matthew 10.5, which has Jesus instructing his disciples “Go not into the way of the Gentiles, and into any city of the Samaritans enter ye not” and John 8.48, which has the Jews say to Jesus “Say we not well that thou art a Samaritan, and hast a devil?” The victim is presumably a Jew, since he is described as on a journey from “Jerusalem to Jericho,” and the story registers disappointment if not surprise that he

is ignored by “a certain priest” and a “Levite” (Luke 10.30-32). The victim feels and shows astonishment and dismay because help is coming from a despised and most unlikely source, after two likely sources have failed him. He is not rejecting that aid.The gesture made by the victim needs more detailed consideration in the light of this understanding of its context. The manual gesture is essentially identical with that made by Robinson Crusoe as he discovers the footprints in the sand (illus. 2).17↤ 17 See Martin Butlin, The Paintings and Drawings of William Blake, 2 vols. (New Haven: Yale UP, 1981) #140r. Here is the text which Blake was illustrating on that occasion: “It happen’d one Day about Noon going towards my Boat, I was exceedingly surpriz’d with the Print of a Man’s naked Foot on the Shore, which was very plain to be seen in the Sand: I stood like one Thunder-struck, or as if I had seen an Apparition. . . .”18↤ 18 Daniel Defoe, Robinson Crusoe, ed. M. Shinagel (New York: Norton, 1975) 121. The drawing actually shows the time as either sunset or dawn, contrary to the indication of the text, but the visible footprint before Crusoe makes the moment illustrated quite definite. Rodney M. Baine is probably correct in suggesting that Blake chose a setting sun “To heighten Crusoe’s isolation and terror. . . . For that night the fearful Crusoe slept not at all . . .”; “Blake and Defoe” Blake 6 (1972): 52. Defoe’s text makes plainer than could my own words that Crusoe’s gesture is understood by Blake as a sign for surprise. This gesture in turn corresponds closely to, and was doubtless derived from, Le Brun’s description of “Admiration”: “this first and principal Emotion or Passion may be expressed by a person standing bolt upright, with both Hands open and lifted up, his Arms drawn near his Body, and his Feet standing together in the same situation.”19↤ 19 Charles Le Brun, A Method To learn to Design the Passions, trans. John Williams, intro. Alan T. McKenzie (Los Angeles: William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, 1980) 47.

The fact that the victim in Blake’s portrayal of the Good Samaritan is lying down and not standing makes a difference, but not a crucial one, for Bulwer’s Chirologia contains a plate, reproduced by Janet Warner, which represents simply two hands raised from the wrist with the identification “Admiror.”20↤ 20 Janet Warner, Blake and the Language of Art (Kingston: McGill-Queen’s Press, 1984) 51. Warner’s book received a rather ungenerous review recently in Blake (24 [1990]: 65-67), but it would seem that some of the important things that she has to tell us have not yet been absorbed by Blake scholars. Bulwer’s commentary on this gesture is as follows: “To throw up the Hands to heaven is an expression of admiration, amazement, and astonishment, used also by those who flatter and wonderfully praise; and have others in high regard, or extoll anothers speech or action.”21↤ 21 [John Bulwer], Chirologia: or the Naturall Language of the Hand (London, 1644) 29. Bulwer’s text appears to describe a gesture involving arms raised above the head, but the fact that his illustration shows only the hands suggests that the core signifying element in the gesture is the upraising of the hands at the wrist, as is clear in Le Brun.

begin page 68 | ↑ back to topA gesture which has been read as if it were a natural sign easily interpreted intuitively as meaning rejection, is in fact a highly conventional, explicitly coded sign meaning surprise and wonder. As in the case of the serpent, the semiotic status of a sign must be determined before it can be usefully interpreted. As the concept of the hermeneutic circle suggests, detail and general context can work together to produce a persuasive reading.

Having now focused this gesture, we can see that it is in fact very common in Blake’s work, and occurs frequently in the Night Thoughts illustrations. Its meaning there seems to range from joyful surprise at the resurrection (NT 318), through awed shock at apocalypse (NT 429), to fearful recognition of guilt, condemnation, and disaster (NT 18, 53). But through all these changes there remains the root sense of surprise, astonishment. The gesture seems never to mean simply rejection, though obviously there can be an element of rejection in the shocked recognition of unwelcome news.

This interpretation of the victim’s gesture as representing not rejection but profound surprise at the unexpected source of the offered help can be confirmed from another perspective. The victim’s eyes fix not the allegedly threatening serpent but the Samaritan’s eyes; it is the human source of the help that is the focus of the victim’s response, and not the medical apparatus involved. The victim’s response is not to be read as a rejection; he is simply very, very surprised. And the look on the face of the Samaritan is one of concern and compassion; nothing more complex or questionable than that.

The horse seems equally innocent of ethical ambiguity or menace. Grant’s attempt to blacken him by association with the allegedly sinister donkey that is “included among the ominous familiars” of Hecate in the color print of that name is an unnecessary hypothesis. I have in a previous essay made a tentative case for regarding the donkey in Hecate as merely a beast of burden;22↤ 22 Christopher Heppner, “Reading Blake’s Designs: Pity and Hecate” BRH 84 (1981) 363. I can add here that it is distinguished from the “ominous familiars” by the fact that it is harmlessly and realistically grazing. Satan’s familiars are usually provided for in less mundane ways; traditionally, a witch’s familiar drank from the third teat which was one of the defining features of witches in the post-classical era. In addition, the donkey is the only animal in the print that is not depicted as gazing at something or somebody; it is simply minding its own business in a most unthreatening fashion. As C. H. Collins Baker noted, the basic design of this ass was taken by Blake from an engraving of the Repose in Browne’s Ars Pictoria, and was used again in a painting of The Repose of the Holy Family in Egypt.23↤ 23 C. H.Collins Baker, “The Sources of Blake’s Pictorial Expression” reprinted in Robert N. Essick, ed., The Visionary Hand (Los Angeles: Hennessey & Ingalls, 1973) 116-19. All of the other associations of this animal are innocent and even benign; I see no reason to assume any change in Blake’s version of it in the Good Samaritan.

The difficulties encountered up to now in interpreting this design stem from the initial critical decision on how to approach it. Let us look at the design again in its full context. As the asterisk beside the text in both the original water color and the later engraving indicates, Blake began with the line “Love, and love only, is the loan for love.” This line is set in the broader context of a musing on the theme of friendship, which blooms “abroad” for those “who cherish it at home,” but resists the blandishments of power and money: “Can gold gain friendship?” Blake, looking for a story with which to illustrate the subject, decided upon the story of the Good Samaritan.

But the story does not exactly illustrate Young’s point. The parable of the Good Samaritan is an illustration of the problem of defining just who is my neighbor, a problem opened by the lawyer’s trick question to Jesus: “Master, what shall I do to inherit eternal life?” (Luke 10.25). In response to Jesus’s question about the status of the law on this point, the lawyer interprets it as saying: “Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy strength, and with all thy mind; and thy neighbour as thyself.” In response to Jesus’s approbation, the lawyer then asks “And who is my neighbour?” It is at this point that Jesus tells the story, which he concludes by asking: “Which now of these three [priest, Levite, Samaritan], thinkest thou, was neighbour unto him that fell among thieves?” and the obvious answer comes “He that showed mercy on him.” To which Jesus replies “Go, and do thou likewise.”

True neighborly love does not consist in simply returning love for love, or even in buying love by lending or giving love, but in freely giving love to those most culturally remote from us when they are in need, even if they have shown nothing but scorn towards us in the past, and are not likely to change in the future, or ever have occasion to return that love. The critique of Young, in other words, takes place at the level of the choice of the illustrative story; Young has been implicitly corrected for the legalistic and monetary mere equivalence of his “Love . . . is the loan for love.” As Young goes on to say, “nor hope to find / A friend, but what has found a friend in three.” The story of the Good Samaritan is a rejection of that impoverished doctrine; the victim has just found a true friend in one towards whom he had always expressed contempt. Jesus as the Samaritan represents precisely the possibility of advancing beyond the position outlined by Young.

The critical problems with this design have been rooted in a reluctance to spend enough time and thought on the relationship between the text of the story being illustrated (that of the Good Samaritan) and Blake’s design, and on the details of that design in relation to the traditions of pictorial meaning as Blake knew and understood them. In the place of that process of working through to the meaning of begin page 69 | ↑ back to top Blake’s design there has been premature haste to move to a consideration of the relationship between Blake and the poet he is commenting on, a consideration largely controlled by an understanding of Blake’s overall position as laid out in his major poetic texts. As I have tried to show, Blake’s designs can bear Blakean meanings without being in any way direct illustrations of his own poetic texts. The commentators have been right to feel a critical space between Blake’s design and Young’s text, but have looked in the wrong place for the evidence. It does not lie in Blake’s version of the story of the Good Samaritan, which he has handled with his usual close attention to the details of the biblical story, assisted by the addition of some traditionally based iconographic details. It lies rather in his choice of that particular story with which to illustrate this portion of Young’s text, a story whose relevance is by no means immediately obvious, and which holds a powerful critique of Young’s economy of love as exposed at this moment of the poem.