minute particular

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

Blake And Thomas Burnet’s Sacred Theory Of The Earth

The importance of Thomas Burnet to some of William Blake’s contemporaries is well recognized. One of Coleridge’s unrealized projects was “Burnet’s theoria telluris translated into blank verse, the originals at the bottom of the page.”1↤ 1 The Notebooks of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, ed. Kathleen Coburn (New York: Pantheon Books, 1957) 1: no. 61. Wordsworth wrote parts of Burnet’s theory into The Ruined Cottage and The Prelude.2↤ 2 See M. H. Abrams, Natural Supernaturalism: Tradition and Revolution in Romantic Literature (New York: W. W. Norton, 1973 [1971]) 99-106. The young Shelley may have been introduced by his millennialist friend John Frank Newton to Burnet’s ideas.3↤ 3 See Kenneth Neill Cameron, The Young Shelley: Genesis of A Radical (New York: Collier Books, 1962 [1950]) 428n54. There is much in Burnet that Blake too would have found of interest. In his recent major study of Blake and the sublime, Vincent Arthur De Luca convincingly suggests that Blake was influenced by Burnet in constructing his own myth of the origins of the present state of the earth, including the creation of Urizen’s world in The [First] Book of Urizen and the third Night of Vala, and the situation of the Mundane Egg in Milton.4↤ 4 Words of Eternity: Blake and the Poetics of the Sublime (Princeton: Princeton UP, 1991) 155-56, 157, 158, 162-63, 191. De Luca’s fine exposition is limited to the first two Books of Burnet’s work, comprising his accounts of the Creation, the Deluge, and the original Paradise. The relevance to Blake of the third and fourth Books, concerning the Conflagration and the New Heavens and New Earth, remains to be discussed, as does another aspect of Burnet’s book—its illustrations.

Early editions of The [Sacred] Theory of the Earth5↤ 5 What I refer to as Burnet’s “book” was originally published in Latin in two parts, each of which was Englished by Burnet himself, as follows: Part I in Latin, 1681, in English 1684; Part II in Latin 1689, in English 1690. See M. C. Jacob and W. A. Lockwood, “Political Millennialism and Burnet’s Sacred Theory,” Science Studies 2 (1972): 265-79. The printed title pages of the first three editions omit the word “Sacred,” which does, however, appear in the engraved frontispieces. were illustrated with anonymous but well executed engravings that are likely to have interested Blake the engraver as well as Blake the cosmogonist. (A comparison of the first three editions in English shows no significant differences among the designs.) The first is a striking frontispiece depicting Jesus standing above seven disks that, counting clockwise, appear as follows: begin page 76 | ↑ back to top

1. A dark circle filled with jumbled marks, similar to the illustration of the earth in its chaos on page 34.

2. A light disk matching the representation of the “first earth” before its dissolution on page 67.

3. The earth under water with Noah’s ark, accompanied by angels, floating on the waves, as engraved on page 101.

4. The earth with its continents formed, as in the foldout engraving following page 150.

5. The earth in flames. This is the subject matter of the third Book, “Concerning the Conflagration,” in volume 2.

6. The restored first earth, virtually identical with the second disk, upon which the millennial world will be created.

7. A sun, illustrating Burnet’s conviction “that the Earth, after the last day of Judgment, will be changed into the nature of a Sun, or of a fixt Star. . . .”6↤ 6 The Theory of the Earth Containing an Account of the Original of the Earth and of all the General Changes Which it bath already undergone, or is to undergo Till the Consummation of all Things. 3rd. ed. 2 vols. (London, 1697). Subsequent references are to this edition, cited by volume and page numbers.

The first and third disks are of special interest to us here. “There is a particular pleasure to see things in their Origins,” writes Burnet, “and by what degrees and successive changes they ran into that order and state we see them afterwards, when completed” (1: 35). According to the Sacred Theory, the beginning of the earth was as a Chaos in which the elements of earth, air, and water were intermixed before their separation. This is pictured as the first disk of the frontispiece and, in larger scale, on page 36 as a mass of jumbled particles (illus.1). This disk bears a striking resemblance to the one in the frontispiece of Blake’s Song of Los (illus. 2), where the sun is either eclipsed by another heavenly body forming in front of it or is itself in the process of formation. In either case, Blake has seemingly borrowed his visual conception from Burnet’s book.

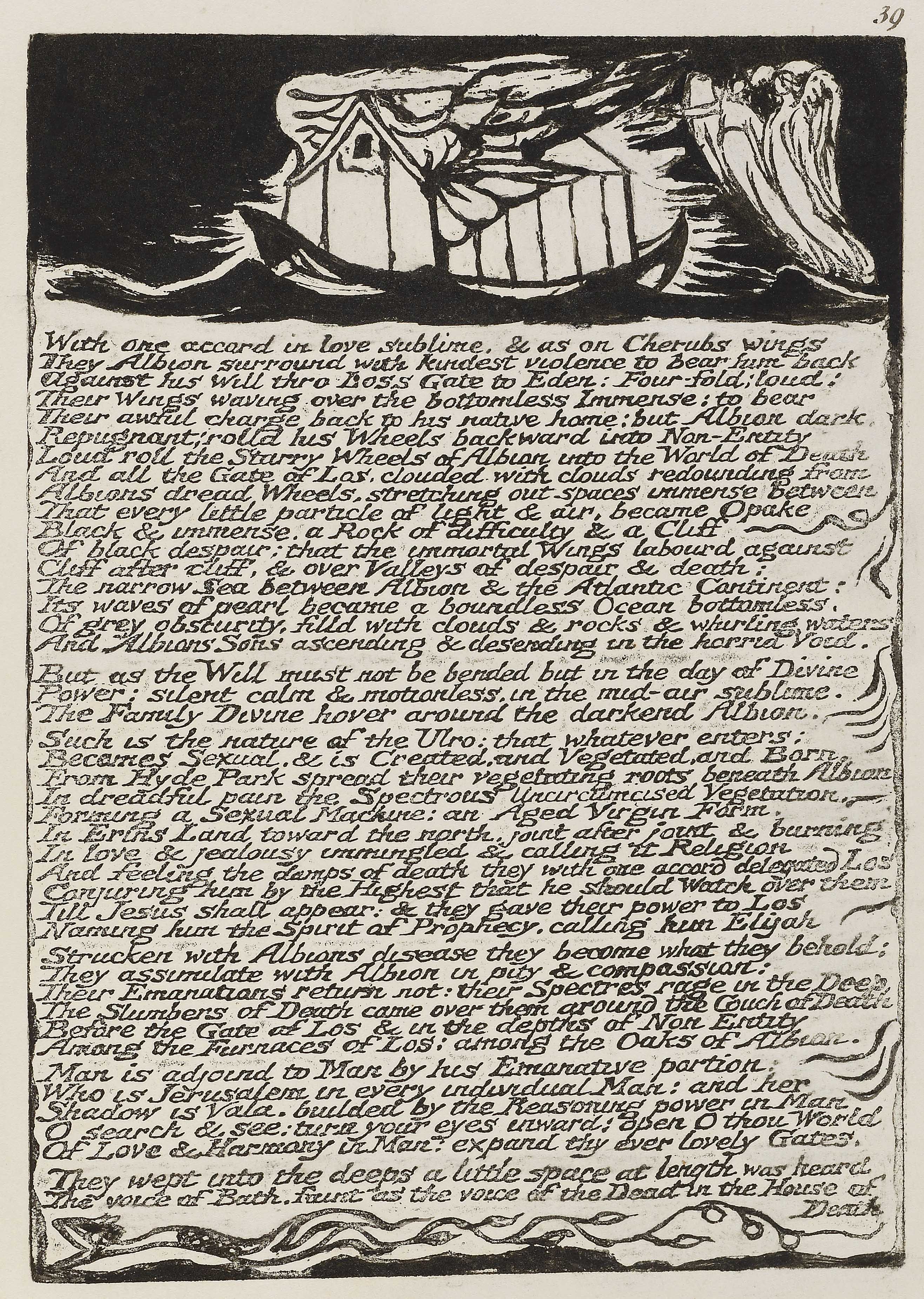

Another such borrowing occurs with respect to the Deluge scene of the third disk in the frontispiece. After the formation of a perfectly smooth, egg-like earth, pictured as consisting of four concrete, flattened-out circles (illustrated on page 44), the waters were contained in the Abyss. When the crust of the earth dried, however, it cracked. “The whole fabrick brake, and the frame of the Earth was torn in pieces, as by an Earthquake” (1: 50). Portions of the crust fell into the Abyss and forced out the water, which then covered the land. On page 68 an engraving enlarges the third disk of the frontispiece, showing the earth covered by water and a houseboat-like Ark accompanied by two angels (illus. 3). If we compare this part of the illustration in Burnet to Blake’s design in the upper part of Jerusalem 39[44] (illus. 4), the resemblance is remarkable. Although other sources for Blake’s arks have been suggested,7↤ 7 See Nicolas O. Warner. “Blake’s MoonArk Symbolism.” Blake 14 (1980-81): 44-59. none is as close to this particular Jerusalem design as the one pictured in the Sacred Theory.

Our discussion so far has been about Burnet’s first volume, comprising Books I and II, which concern the creation of the earth, the original Paradise, and the Deluge. Books III and IV, which treat of the end of the world and the millennium, also deserve some attention. A short sketch of Burnet’s chief ideas about these events will suggest why Blake would have found them of interest, especially as regards the structure of time, the Conflagration that will end the earth as we know it, and the regeneration of all things in the Millennium.

Burnet cites the Jews’ belief that the world will last 6,000 years, a tradition that he says derives from “Elias the Rabbin, or Cabbalist” (2: 23). In M 24 (E 121), “Los is by mortals nam’d Time” begin page 77 | ↑ back to top (67); “He is the Spirit of Prophecy the ever apparent Elias” (71). In 22: 15-7 (E 117) Los says:

I am that Shadowy Prophet who Six Thousand Years agoAccording to the Sacred Theory, the six days of the world-week would be followed by the sabbath of the Millennium on the model of Moses’ septenaries: six days of creation, then a sabbath, after six years a sabbath year, and after a sabbath of years a year of Jubilee. “All these lesser revolutions,” writes Burnet, “seem to me to point at the grand Revolution, the great Sabbath or Jubilee, after six Millenaries . . .” (2: 102). Compare Milton 23: 55 (E 119):

Fell from my station in the Eternal Bosom. Six Thousand Years

Are finishd. I return!

Six Thousand years are passd away the end approaches fast[.]Before the advent of this great Sabbath or Millennium, however, the world as we know it must be destroyed by fire.

Burnet places great emphasis on a physical description of what the final Conflagration will be like (2: 73-74), citing 2 Thess. 7-9 and the “one general Fire” of Lucan’s Pharsalia. Such a conflagration occupies much of pages 118-20 of Night the Ninth of The Four Zoas, and Milton Los tells his sons:

Wait till the Judgment is past, till the Creation is consumedAfter the burning of the earth there will occur “the Regeneration or Renovation” of the world prophesied in Isaiah 65 and referred to by Jesus in Matt. 19.28 (Burnet 2: 112-13). Christ will return to usher in a millennial state in which humankind will live in “Indolency and Plenty” (2: 126) but will nevertheless enjoy the extension of knowledge, especially of the sun (2: 142). The millennial state will be characterized by universal peace, righteousness, and the absence of pain (2: 126). The position of the axis of the earth will be set parallel to the axis of the Ecliptic, as it was in antediluvian Eden, creating a perpetual spring, Similarly, in Blake’s regained paradise of Night the Ninth of The Four Zoas, where justice is executed upon the tyrants and warriors (123), the Regenerate Man presides over the feast of Eternals (132-33), and “the fresh Earth beams forth ten thousand thousand springs of life” (139: 3). For both authors, the seeds of such a vision lie in a tradition of Christian eschatology that emphasized the concrete, physical aspects of the millennium, and it is not possible to say precisely where Blake is indebted to Burnet and where it is a matter of a common tradition. Nevertheless, the many similarities between their scenarios for the future of the earth, as well as the visual correspondences discussed earlier, strongly suggest that Blake was familiar with The Sacred Theory of the Earth.

And then rush forward with me into the glorious spiritual

Vegetation; the Supper of the Lamb & his Bride; and the

Awakening of Albion our friend and ancient companion. [25: 59-62]