minute particular

Two Newly Identified Sketches for Thomas Commins’s An Elegy and Further Rediscovered Drawings of the 1780s

Three typical pen and wash drawings of the 1780’s, two on one sheet of paper, have turned up in the United States. Two seem to be related to Thomas Commin’s An Elegy, while the other appears to be an independent composition.1↤ 1 I am indebted to Henry Wemyss of Sotheby’s, London, for letting me know of the existence of the drawings in the United States and for letting me have photographs.

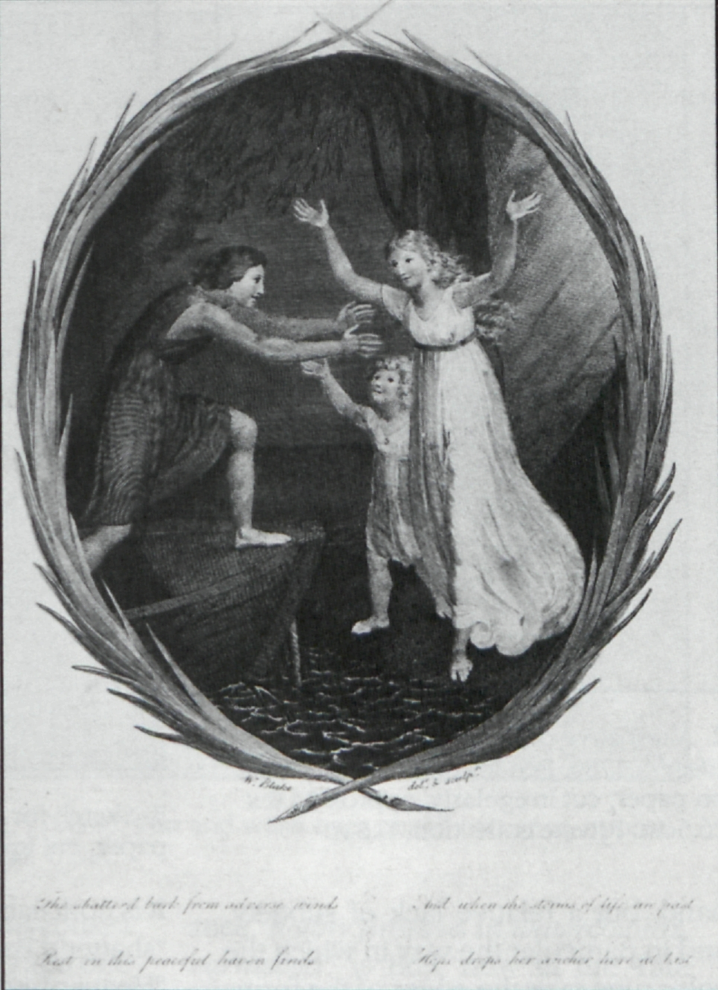

In my catalogue I listed, as number 98, a “Sketch for Thomas Commins’s ‘An Elegy,’” the only evidence for which was the fact that it was in possession of Messrs. Robson in 1913.2↤ 2 Martin Butlin. The Paintings and Drawings of William Blake (New Haven, CT: Yale UP, 1981) 38 no. 98, the engraving repr. pl. 103. In the rest of this article references to my catalogue are given in the form “B98.” The newly identified sheet of drawings may be this work, but the two drawings are different enough from Blake’s finished engraving for the identification to have been easily missed in 1913; if so, there is a further drawing waiting to be discovered.

Blake designed and engraved the frontispiece for Commins’s Elegy, published in 1786. The engraving itself is inscribed “W.Blake delt. & sculpt.” (the identification of the final raised letter

The shatter’d bark from adverse windsBelow is the publisher’s imprint: “Published July 1. 1786 by J. Fentum No 78 Corner of Salisbury Street, Strand” (on the British Museum copy the final word is almost lost through the wearing of the paper; it is reconstructed here on the basis of the imprint at the head of the music itself).

Rest in this peaceful haven finds

And when the storms of life are past

Hope drops her anchor here at last.

The engraved design shows a young man leaping out of an anchored boat towards a young woman and child, presumably his family, awaiting him on the shore; behind are trees and what appears to be a cliff (illus. 1). The design is framed by a border of palm fronds, forming an upright oval. (The British Museum copy is colored by begin page 22 | ↑ back to top

The full title of Commins’s Elegy, at the head of the first of five pages of music (printed on three sheets of paper), is “AN ELEGY / set to Music by / THOs: Commins,/ Organist of Penzance, Cornwall./LONDON./Printed & sold by J. Fentum, No 78, corner Salisbury St.., Strand.” The verses accompanying the music run (with a long “s” used whenever appropriate):

Sigh not ye winds as passing o’er the Chambers of the dead ye fly,

Weep not ye dews for these no more shall ever weep, shall ever sigh.

Why mourn the throbbing heart at rest

How still it lies within the breast

Why mourn since death presents us peace,

And in the grave our sorrows cease.

[The last two lines are repeated, followed by the first two lines]

The shatter’d Bark from adverse winds

Rest in this peaceful Heaven finds

And when the storms of Life are past

Hope drops her Anchor here at last.

[The last two lines are repeated].

The recto of the rediscovered sheet of drawings shows a much varied version of the engraved design, in reverse (illus. 2). An older, bearded man gets out of the boat in a considerably less agile fashion, looking apprehensively over his shoulder the while; two angels await him on the shore, and there are trees behind. The composition is again an upright oval, within a roughly drawn outline. The presence of the angels gives a greater feeling of Heaven than in the engraving.

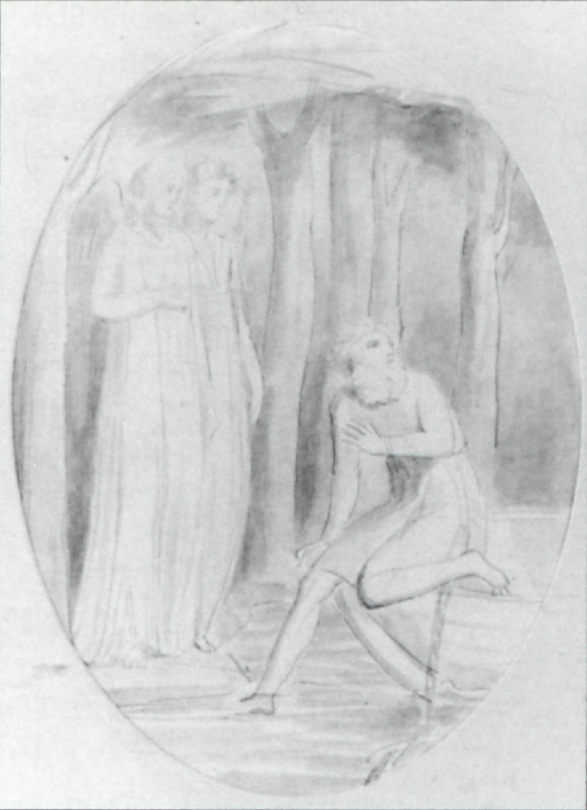

This however is absent from the drawing on the reverse, in which a young man has just finished rowing his boat into a small creek or haven (illus. 3). There are no figures on the shore. Again there are trees behind but of a totally different kind. The composition is an oblong. In the lower right-hand quarter of the drawing there is what may be the beginnings of an oval composition which would have continued to the right over the cut edge of the existing paper. This drawing presumably preceded the one on the recto, before even the format of the final engraving had been determined.

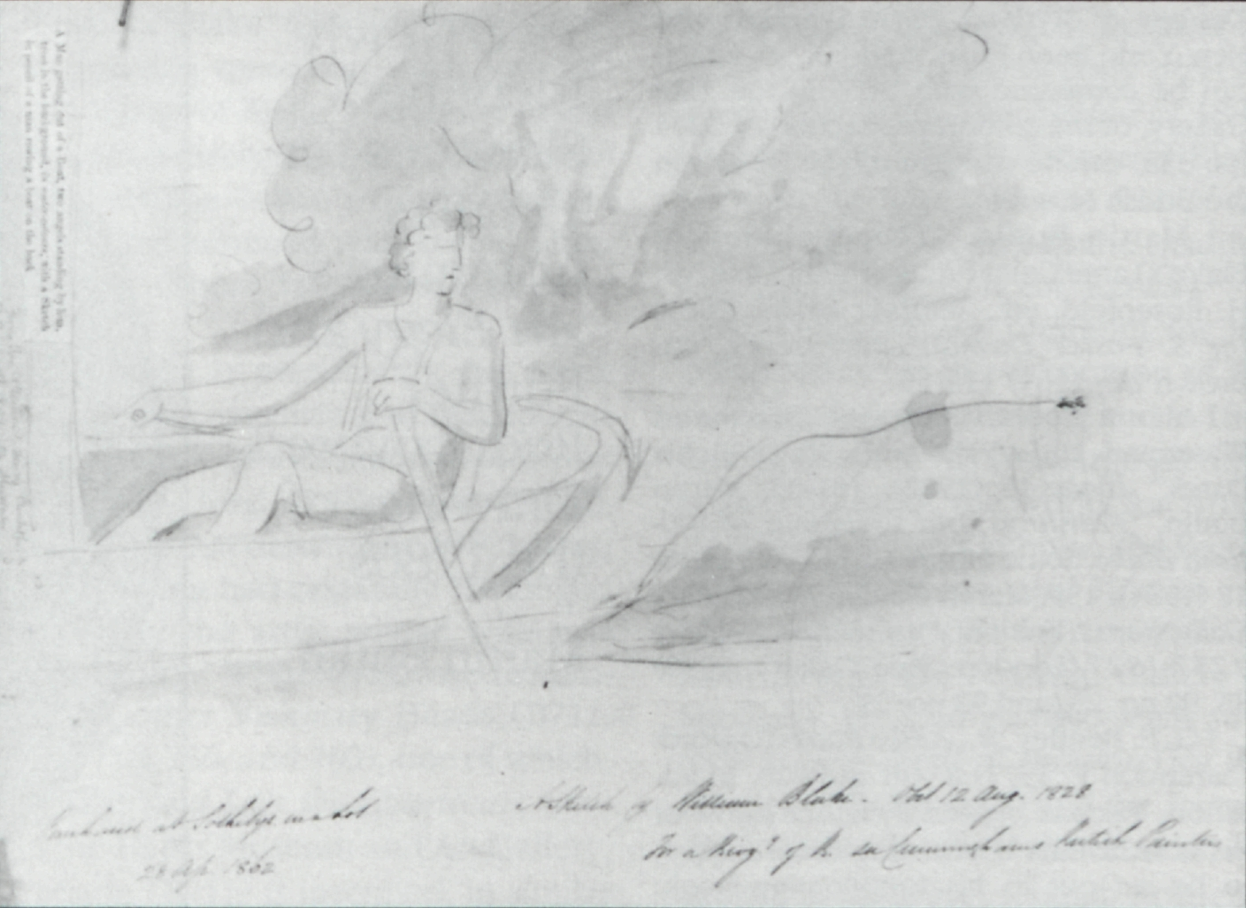

Another rediscovered drawing in the same American collection, and apparently sharing the same provenance, is similar in style and, like the two drawings here related to Commins’s Elegy, datable to the early or mid seventeen eighties (illus. 4). It shows three groups of figures in what seems to be Heaven. Three bearded men float in the air just to the left of center, facing the spectator, and another group of three figures, one old, two young, float on the right facing two middle-aged dark-bearded men who soar up from the left. In general character, and in the long flowing robes ending in scroll-like folds, the drawing resembles the group of pen and ink drawings illustrating scenes from the Old Testament, B112-4 in my catalogue.

Various inscriptions together with an attached piece of paper bearing a printed title on the back of the first drawing indicate that it comes from the collection of Henry Cunliffe “of the South Kensington Museum.” Two inscriptions in ink are similar in handwriting begin page 23 | ↑ back to top and in the mistakes they embody to inscriptions on other drawings that belonged to Henry Cunliffe, B69, 113, 119A, 144, 190 and 650. The inscription to the right reads “A Sketch by William Blake. Obit 12 Aug. 1828/For a BiogY of B. see Cunninghams British Painters.” The reference is to Allan Cunningham’s Lives of the Most Eminent British Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, first published in 1830 and again, with a more balanced account of Blake, the same year; this is the source for the mistaken date of Blake’s death (actually 1827). The inscription to the left reads “Purchased at Sothebys in a Lot/28 Ap. 1862.” Again there is a mistake: the anonymous sale, but one long identified as being of works from the collection of Frederick Tatham, took place on the 29th of April.

A further inscription, in pencil and running along the left-hand side of the drawing, reads “From the Collection of Henry Cunliffe/of the South Kensington Museum.” To the left of this is a printed title, “A Man getting out of a Boat, two angels standing by him,/trees in the background, in water-colours, with a Sketch/in pencil of a man rowing a boat on the back.” This can be identified as coming from the catalogue of the sale at Sotheby’s on 11 May 1895 of, inter alia, “. . . A Series of Drawings by W. Blake, The Property of the Late Henry Cunliffe, Esq.. ..”; the title is that of lot 105, bought by Keppel for sixteen shillings.

The works from the Cunliffe collection in the 1895 sale comprise, as well as four lots by other artists, 10 lots containing works attributed to Blake, numbers 96 to 105 (plus an india proof impression of the portrait by Linnell of Blake), but none of the more important illuminated books that passed to Henry Cunliffe’s nephew Walter, grandfather of the present Lord Cunliffe. With the reappearance of these two sheets of drawings it seems that one can now identify all the drawings in the 1895 sale and, in turn, those purchased by Henry Cunliffe in 1862.

The 10 lots containing Blakes consist of 13 works in all, 12 drawings and one print, although not every individual work is described and even those that are described are often described in fairly vague terms. Certain lots can be identified straightaway: 96, “A Group of Five Figures (one on Horseback), a town in the background with mountains in the distance, the man and woman in the centre are supposed to represent Blake and his Wife, a highly finished drawing in indian ink, apparently intended to illustrate some story” is the finished drawing finally identified in 1978 as an illustration to Robert Bage’s Hermsprong(B682); 97, “PESTILENCE. An allegorical design in water colours of five figures and corpses” is B190, the version of the much repeated composition later, like the Hermsprong illustration, in the collections of William and George Bateson; 100, “The Canterbury Pilgrims, the original drawing by Blake from the picture to reduce the subject to the size of his plate, in pencil” is B654, which was bought in at the 1895 sale, eventually passed to the Hon. Merlin Cunliffe and now belongs to the British Museum; 101, “Jane Shore doing Penance, highly finished in watercolours, varnished” is B69, now in the Tate Gallery; 102, “Queen Emma walking over the red hot plough-shares,” similarly described, is B59, in a private collection; 103, “The Witch of Endor raising Samuel, spirited drawing in water-colours” is B144, now in the New York Public Library; 104, “Good and Evil Spirits contending for the possession of a Child, an allegorical subject in water-colours” is, despite the medium given in the catalogue, the version of the large color print of “1795” formerly in the collection of Mr. & Mrs. John Hay Whitney, B324.

This leaves lots 98 and 99, which together with lots 103 and the rediscovered lot 105 were bought by Keppel, apparently the New York dealer Frederick Keppel, whose son David gave B119A, a drawing of Goliath cursing David, to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in 1914; Frederick himself had bequeathed an impression of The Accusers to the same museum in October 1913.3↤ 3 Robert N. Essick, The Separate Plates of William Blake (Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1983) 33 no. 3D. The only other recorded purchase of a Blake by Keppel apart from those at this sale was at Sotheby’s on 8 July 1895 when he bought lot 125, Death on a Pale Horse, begin page 24 | ↑ back to top now in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge (B517). In addition, in about 1919-20 his firm owned the separate color-printed design from plate 12 of Urizen now in the Pierpont Morgan Library, New York (B261 10), and also a copy of the title-page to Europe.4↤ 4 G. E. Bentley, Jr., Blake Books (Oxford: Clarendon P, 1977) 162.

Lot 98 is described as “A Sketch in sepia of Angels with spirits of women approaching them; and two other Sketches.” Lot 99 was “A Group of Six Greek Warriors, in pen and ink; and a fine impression of the Child of Nature, after C. Borckhardt, by W. Blake, fastened together at the corners.” It is tempting to identify the drawing of eight airborne figures, which seems to have the same provenance as lot 105, definitely bought by Keppel, as the main work in lot 98, the “Sketch in sepia of Angels with the spirits of women approaching them.” This allows for the habitual inaccuracy of descriptions in sale catalogues, particularly from as long ago as 1895: at a very quick look two of the figures on the right just could be women!

Two further drawings with typical Cunliffe inscriptions on the back are otherwise unaccounted for in the 1895 sale: B113, The Elders of Israel receiving the Ten Commandments (?), and B119A, Goliath cursing David, already mentioned as having belonged to David Keppel. This last, again allowing for a fair laxity in description, could, given the round shields carried by three of its six figures, be the “Group of Six Greek Warriors” of lot 99. Assuming one of the undescribed drawings in lot 98 to be B113, The Elders of Israel . . ., one further work remains to be discovered and, conveniently, one of the drawings reported in my last article on rediscovered Blakes seems to fit the gap.5↤ 5 Martin Butlin, “Six New Early Drawings by William Blake and a Reattribution,” Blake 23 (1989) 110-11, repr. fig. 6. This is the sketch for Joseph’s Brethren bowing before him discovered by David Bindman in Berlin which also, David Bindman tells me, bears the typical Cunliffe inscription “Purchased in a Lot at Sothebys 28 April 1862 HC”[e] together with “A Sketch by William Blake Obit 12 August 1828./In Cunninghams Lives of British Painters Ch.1 Blake”; there is also an inscription matching the pencil inscription on the drawing for Commins’s Elegy, “From the collection of Henry Cunliffe of the South Kensington Museum.”

It is of course tempting to equate any known drawing one can find with those that one knows to be missing, but at least the total number of works now matches up and, although I have been caught out making similar identifications in the past that have subsequently proved to be inaccurate, it is at least for the present a working hypothesis that we now have all the drawings sold by Henry Cunliffe in 1895. One can also venture further and see how these 12 drawings fit with the only 12 works to have been bought by Toovey in the Frederick Tatham sale held at Sotheby’s on 29 April 1862, some of which can quite definitely be shown to have been in Henry Cunliffe’s collection. The lots bought by Toovey were as follows: 161, “The Original reduced Drawing of the Canterbury Pilgrimage, from which he [Blake] engraved his plate,” lot 100 in 1895, B654; 170, “A Pestilence, and other designs, in indian ink,” six works in all, of which the named work was lot 97 in 1895, B190; 171, “Queen Emma walking over the red hot Ploughshares, and Jane Shore doing Penance, both highly finished in colours,” lots 102 and 101 respectively in 1895, B59 and 69; 175, “The Witch of Endor raising the Spirit of Samuel, in colours,” lot 103 in 1895, B144; 182, “An Allegorical Subject - A Man holding a Child, with a chained demon issuing from a fiery abyss, highly finished in colours,” lot 104 in 1895, B324; and 184, “A Design, apparently intended in illustration of a tale, highly finished in indian ink,” lot 96 in 1895, B682. Lot 195 was also bought by Toovey, “Another set” of Songs of Innocence and of Experience “wanting three plates,” the posthumous Copy i still in the Cunliffe collection. The five unidentified works in lot 170, all described as being “in indian ink,” can therefore be equated with the following five works sold in 1895: 98, “A Sketch in sepia of Angels . . . and two other Sketches,” three works in all; 99, “A Group of Six Greek Warriors, in pen and ink,” sold with the print of the “Child of Nature”; and 105, “A Man getting out of a Boat . . . in watercolours, with a Sketch in pencil of a man rowing a boat on the back.” Q.E.D.!

After all this supposition it should be easy enough to say something about “Henry Cunliffe of the South Kensington Museum.” But, despite the helpfulness of the present Lord Cunliffe and of Ronald Parkinson and his colleagues at the Victoria and Albert Museum, as the South Kensington Museum is now known, there seems to be very little information. The present Lord Cunliffe’s great-great-uncle Henry Cunliffe was born in 1827 and died in 1883, apparently in Germany; he is buried in the family plot at Headly in Surrey. He was, typically for a number of mid nineteenth-century Blake collectors, primarily a bibliophile and left his collection of books to his favorite nephew Walter Cunliffe. Unfortunately, there is no record of a Henry Cunliffe at the V & A either in the diaries of Sir Henry Cole, the famous director from its beginnings until 1873 (but there is mention of an Edward Cunliffe), nor is he mentioned in the Precis and Board Minutes between 1863 and 1877. (Just to confuse matters, Sir Francis Philip Cunliffe-Owen, who lived from 1828 until 1894, did work at the Victoria & Albert Museum, having owed his first post in the Science & Art Department to the recommendation of his elder brother Lieutenant Colonel Henry Charles Cunliffe-Owen [1821-67] who, in the course of a mainly military career had been connected with the Great Exhibition of 1851 and was also inspector of Art Schools under the Board of Trade; in 1857 Francis CunliffeOwen became deputy general-superintendent at the South Kensington Museum under Sir Henry Cole, in 1860 assistant director, and in 1873, in succession to Cole, full director. In the 1850s and 1860s the Cunliffe-Owens begin page 25 | ↑ back to top called themselves Owen, which further distinguishes them from our Henry Cunliffe.6↤ 6 For the Cunliffe-Owens see the Dictionary of National Biography.

Two further pen and wash drawings of the 1780s, listed in my catalogue as untraced and not reproduced there, have turned up recently. B139, called The Bed of Death and cataloged as untraced since the sale at Christie’s on 15 July 1957, has re-emerged and been reproduced in the catalogue for the Christie’s sale of 9 July 1991, Lot 86. This has been reproduced and discussed by Robert N. Essick in the last issue of Blake 25 (1992) 148, fig. 4. Whether the drawing really shows a death bed seems unlikely, and it is certainly not related, pace my catalogue entry, to my numbers B137 verso and 138. (The 1991 Christie’s catalogue also reproduces, at lot 85, the Visionary Head of Jonathan in its present state; it was previously reproduced, unrestored, in Blake following its sale at Christie’s on 9 July 1985.7↤ 7 Robert N. Essick, “Blake in the Marketplace 1985,” Blake 20 (1986) repr. p. 16, fig. 3.

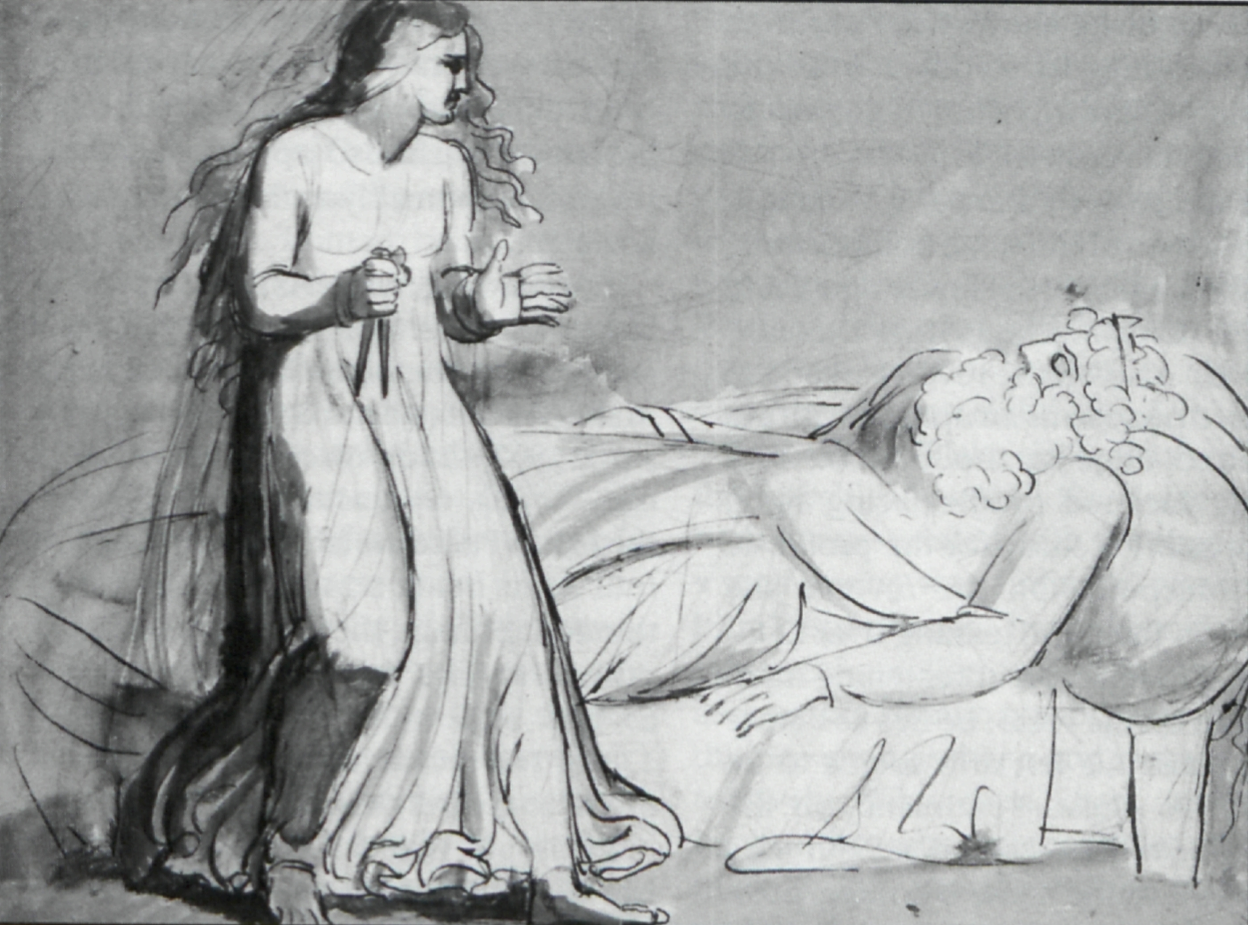

The other rediscovered drawing, Lady Macbeth approaching the Sleeping Duncan (illus. 5) is much more exciting.8↤ 8 Andrew Wyld of Thos. Agnew & Sons, Ltd, told me about the drawing in London, let me examine it and, again, supplied photographs. I am most grateful to my friends among art dealers and auctioneers in keeping me informed about works by Blake as they turn up. Its position in my catalogue, as B249, is too late; rather, as hinted at in my entry, it should be placed earlier as one of the pen and wash drawings of about 1785. The full medium is pen and wash over pencil on laid paper watermarked “JWHATMAN.” As well as the usual grey wash there is some brown along the draperies down the back of Lady Macbeth and below her left hand. The paper seems to have been trimmed all round, cutting the inscription “Blake,” perhaps a signature, in the lower right-hand corner. The drawing illustrates the passage from act II, scene ii of Macbeth, where Lady Macbeth describes how

I laid their daggers ready,This is in fulfillment of Macbeth’s suggestion, in act I, scene vii, that he should use the daggers belonging to Duncan’s two chamberlains, made drunk by Lady Macbeth, so that it would look as if they had committed

He could not miss ’em. Had he not resembled

My father as he slept, I had done’t

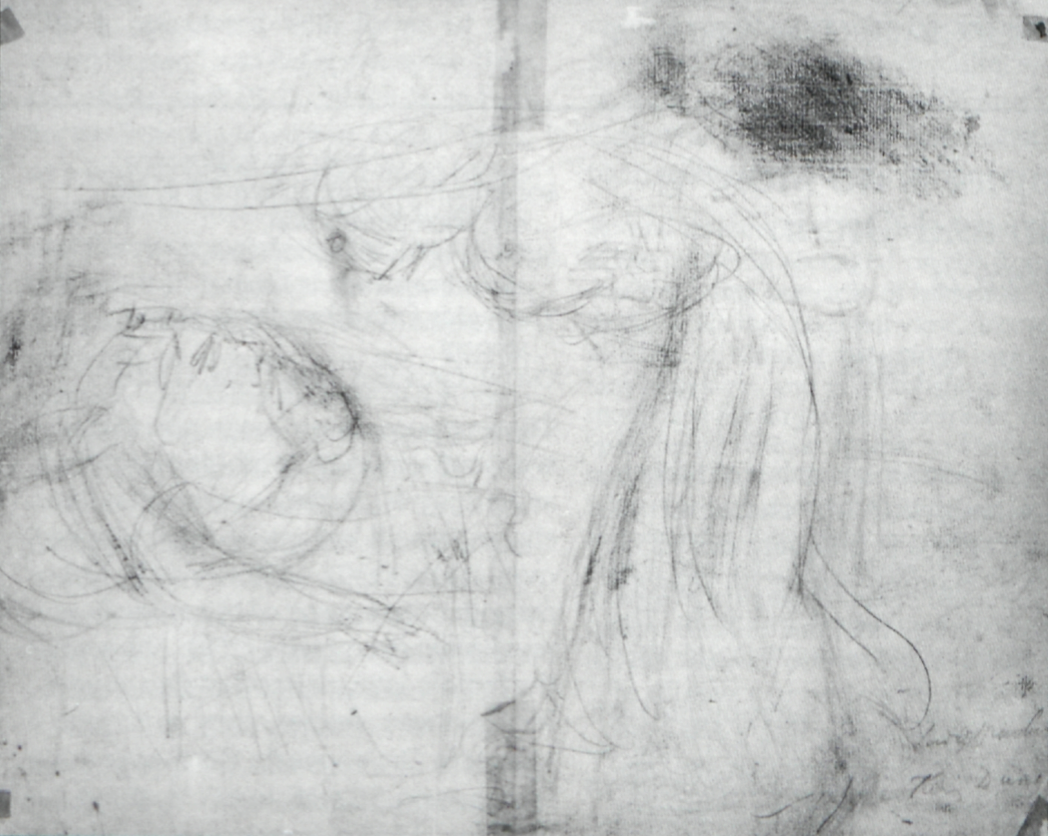

On the reverse there is a variant in pencil alone of the same composition, inscribed, again in the lower right-hand corner, “Lady Macbeth/King Duncan” (illus. 6). Also on the reverse, with the paper to be seen as an upright with the left-hand edge at the bottom, is a slightly inclined profile facing right, just possibly a study for the profile of Lady Macbeth. On the reverse she stands on the right, leaning over Duncan in a much more threatening manner than on the recto; he lies as before except that his left arm seems to lie across his chest. Pentimenti on the recto show that Lady Macbeth was originally in the same stooping position as on the verso; Blake also drew her in an intermediary position before finally adopting the present upright stance. The drawings therefore are a particularly interesting example of how Blake improvised his compositions. Some of the forms of the recto have come out on the verso, perhaps because it was drawn with the paper laid on a dirty surface, and some of the brownish wash also appears on the reverse, presumably as the result of an accident.

The drawing, which is listed by William Rossetti as indicated in my entry, seems to be one of the items in lot 165 in the Tatham sale at Sotheby’s on 29 April 1862, “Lady Macbeth and Duncan, Angels conducting the Souls of the Just to Paradise, &c. in indian ink,” four items in all, bought by Palser for thirteen shillings; the lot comes among other drawings that can be identified as pen and wash drawings of the 1780s. The recent history of the drawing is no clearer than was indicated in my entry; all that can be said is that it has recently turned up in the trade. Rossetti’s dismissive description, “Not carried far beyond the outline. Ordinary” seems far from the mark. In fact the drawing is one of the most dramatic and boldly drawn of this whole group.