minute particular

A Possible Corollary Source for The Gates of Paradise 10

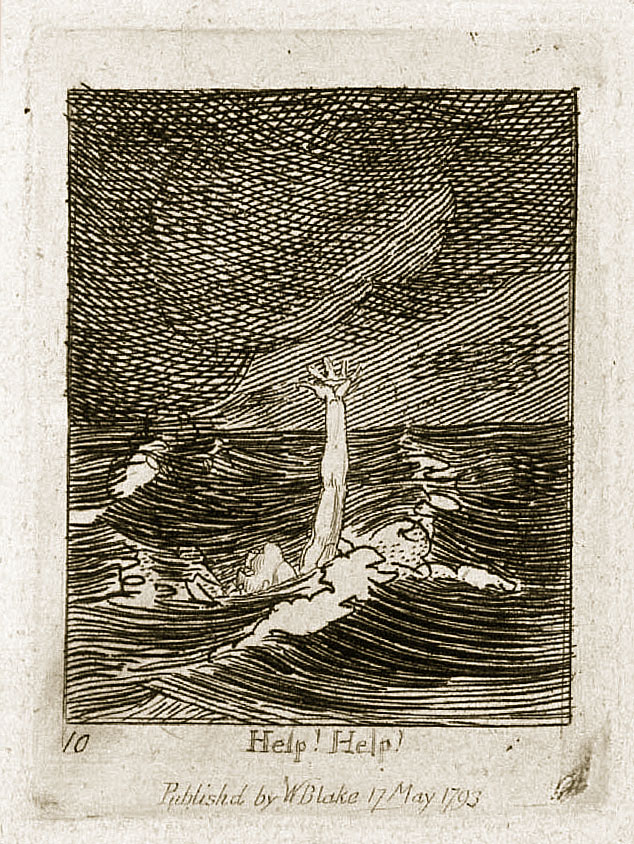

In the course of examining Gerda S. Norvig’s new study, Dark Figures in the Desired Country: Blake’s Illustrations to The Pilgrim’s Progress, I was struck by the author’s discussion of plate 10 of Blake’s 1793 The Gates of Paradise (“Help! Help!”), which discussion echoes David V. Erdman’s earlier argument that a strong connection exists between this plate and the preceding one (“I Want! I Want!”), and a well-known caricature print by James Gillray from the same year, The Slough of Despond.1↤ 1 Gerda S. Norvig, Dark Figures in the Desired Country: Blake’s Illustrations to The Pilgrim’s Progress (Berkeley: U of California P, 1993) 61-69. See also David V. Erdman, Blake: Prophet Against Empire, 3rd ed. (Princeton: Princeton UP, 1977) 203-04 and Erdman, ‘William Blake’s Debt to James Gillray,” Art Quarterly 12 (1949): 165-70. Norvig argues that Gillray deliberately invoked the context of Pilgrim’s Progress, both in his explicit citation of Bunyan’s title (in the title he inscribed at the bottom of the print) and in the verbal and iconographic details he included, and that Blake’s subsequent engravings are therefore indebted both to Gillray and to Bunyan. While both the visual correspondences in Blake’s two engravings (like the similar shapes of the land masses in the distance in the Gillray and “Help! Help!”) and the verbal connections between their captions and Gillray’s print (especially the recurrence of the phrase, “Help! Help!”) certainly support the suggestion that Blake had Gillray’s print in mind, another visual precedent may well be involved here as well.

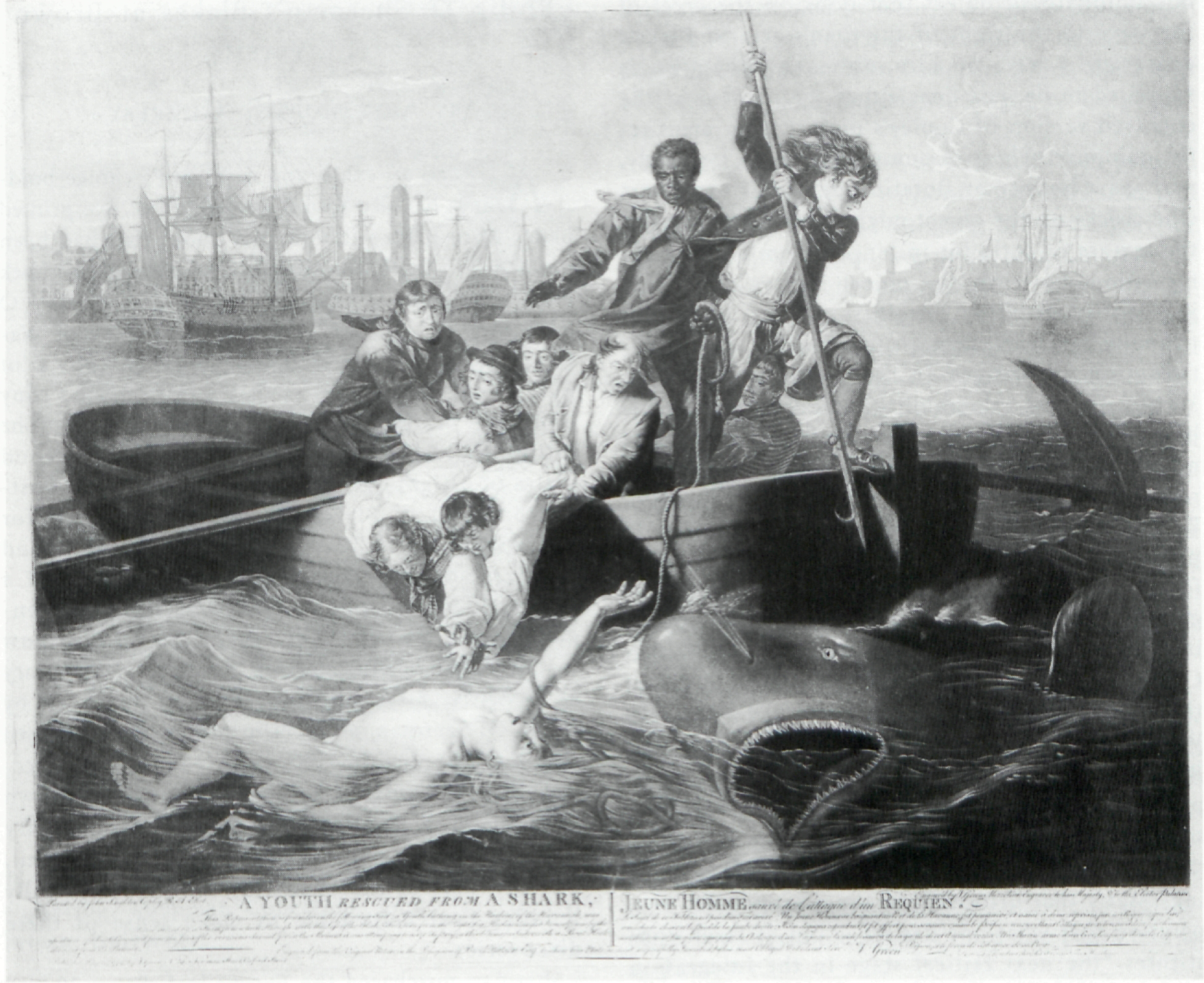

In 1778 the American painter John Singleton Copley’s remarkable painting, Watson and the Shark, became the sensation of that year’s exhibition at the Royal Academy of Art. A contemporary critic fairly brimmed over with praise: “We heartily congratulate our Countrymen on a Genius, who bids fair to rival the great Masters of the Ancient Italian Schools.”2↤ 2 Quoted in William James Williams, A Heritage of American Paintings from the National Gallery of Art (New York: Rutledge Press, 1981) 30. While Blake was not formally admitted to the Royal Academy Schools until 8 October 1779,3↤ 3 David Bindman, Blake as an Artist (Oxford: Phaidon, 1977) 19. it seems scarcely credible that he could have been unaware of the painting that had achieved such popular success in the previous year’s exhibition. Moreover, Copley profited from the large

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

The struggling figure in Blake’s “Help! Help!” bears striking visual resemblances to Copley’s figure of the endangered and seemingly helpless Brook Watson, which figure is itself borrowed from the figure of a helpless child in Raphael’s last altarpiece.7↤ 7 Williams 30. The relationship of Blake’s little figure to Copley’s monumental one becomes even more striking when we recall that in reproductive engraving the engraver generally reverses the right-left orientation of his or her original, which in this case would produce a figure very much like that which Blake has drawn, complete with dramatically extended hand and with hair streaming out and away in the water from the figure’s head. The waves in Blake’s engraving are likewise much like those in Copley’s painting. Norvig makes much of the curious begin page 94 | ↑ back to top unidentified object that bobs on the crest of the wave to the right of the man’s arm in Blake’s engraving. I have no idea, either, of what this is supposed to be, nor does either the painted or the engraved version of Copley’s picture offer any useful guidance. There is something there, certainly, perhaps a bobber or flotation device of some sort (the specks on the object might be taken to suggest the texture of cork, for instance). Even under magnification, however, the object refuses to divulge its identity with any certainty.

Finally, a clear thematic connection exists between the two images. In the Copley the figure of Watson (whose vulnerability is underscored by his being rendered naked) is seemingly faced with imminent destruction: the various efforts of would-be rescuers appear to be both ineffective and too late. Even the life-line that has been offered Watson proves valueless, draped as it is across the extended forearm of the unresponsive Watson. Blake’s engraving only makes physically explicit (by actually isolating the struggling figure) what is implicit in Copley’s painting: the apparently total inability of the struggling figure to help, or to save, himself. Whether we take Geoffrey Keynes’ word that Blake’s emblem is “self-explanatory”—that it depicts “Man drowning helplessly in the materialistic Sea of Time and Space”—or whether we go further and agree with Gerda Norvig that the engraving asserts that drowning in the disappointed recognition that what one desires is out of reach constitutes “the next critical stage in the integration of the whole man,”8↤ 8 William Blake, The Gates of Paradise, ed. Geoffrey Keynes, 3 vols. (London: Trianon Press/Blake Trust, 1968)1: 17; Norvig 65-66. the fact remains that both Blake’s image and Copley’s portray individuals in desperate straits indeed. That Copley’s Watson cannot be helped by his friends would have been less important to Blake—though he would have appreciated the pathos—than the fact that he cannot help himself, as the neglected life-line indicates. It is this thematic connection that seems to me to underscore the validity of recognizing in Blake’s apparent borrowing from Watson and the Shark a connotation that is intellectual as well as merely iconographical.