minute particular

begin page 94 | ↑ back to topPhilip D. Sherman’s Blakes at Brown University

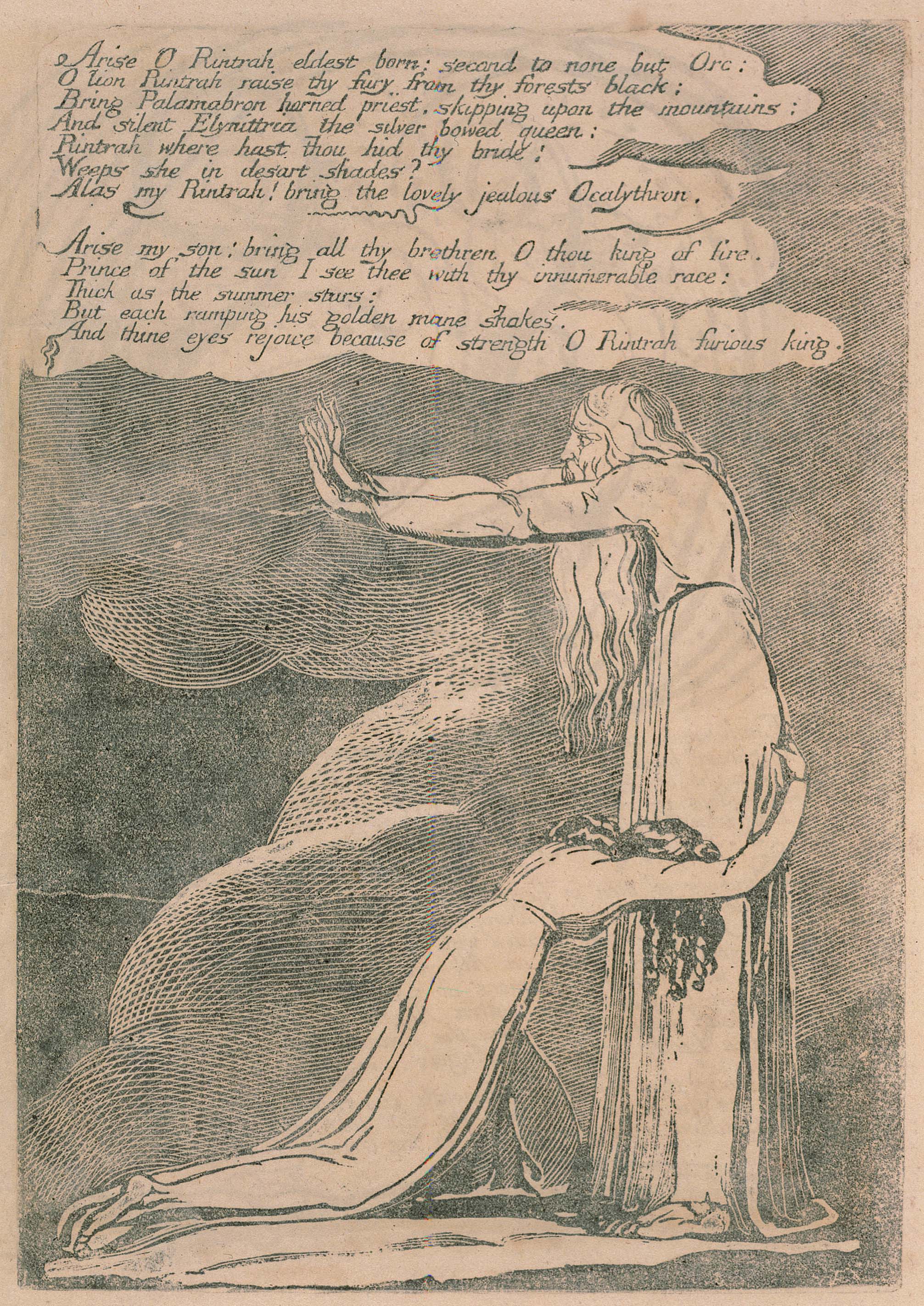

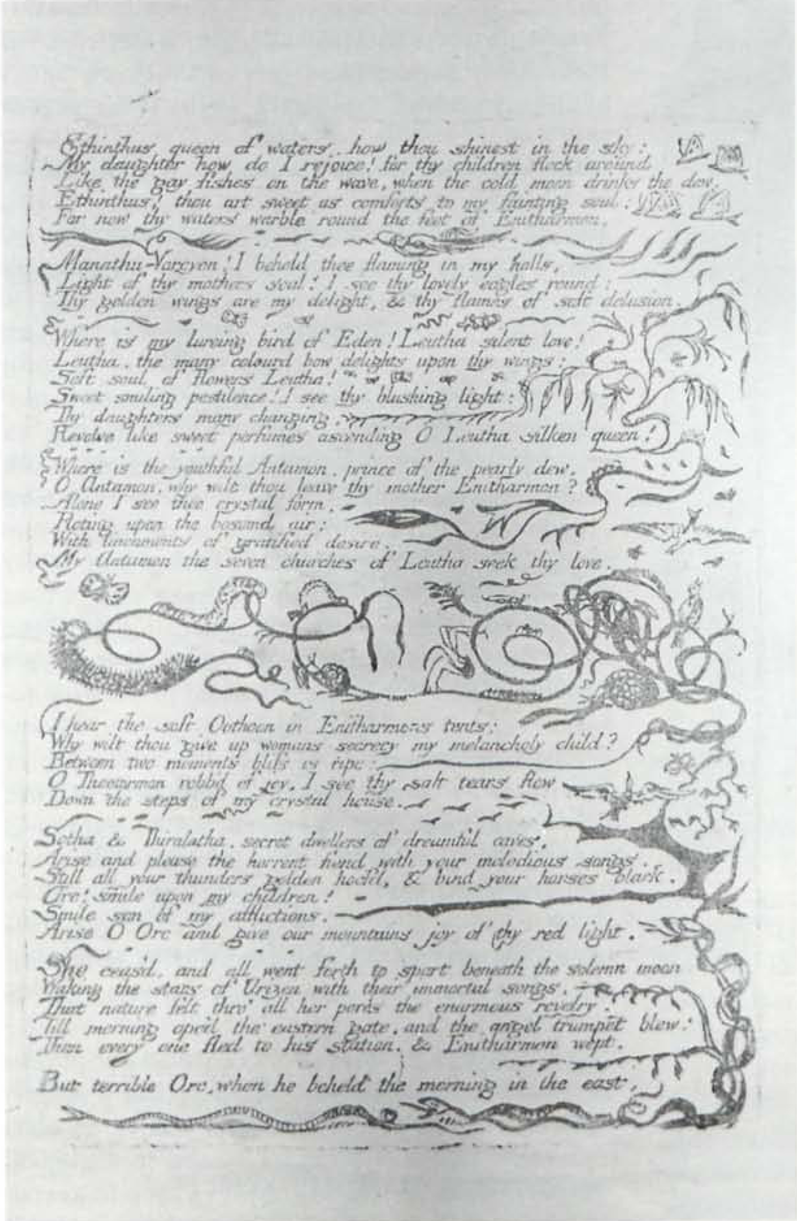

A visit to an exhibition of Brown’s choice holdings has led to the recognition of five printed plates from Blake’s illuminated books that had been untraced: a single leaf bearing on its front and back uncolored impressions of plates 11 (“Arise O Rintrah . . .”) and 17 (“Ethinthus Queen of Waters . . .”) from the assemblage called copy c of Europe and three leaves from the posthumous copy o of Songs bearing uncolored pulls of plates 13 (“The Little Boy lost”), 20 and 21 (the first and second plates of “Night”). These items, along with a posthumous pull of Blake’s wood engraving XIII for Thornton’s Virgil, 1874 restrikes of plates 15 and 20 of the Illustrations of the Book of Job, and a Colnaghi restrike of the fifth state of Blake’s engraving of Chaucers Canterbury Pilgrims, are now in the Koopman collection in the John Hay Library at Brown University. All were given to Brown by Philip D. Sherman, an Oberlin professor and Brown alumnus who died in 1957, as part of a huge collection that he named in honor of Koopman, a Brown librarian. G. E. Bentley, Jr., Robert N. Essick, Mary Lynn Johnson, Charles Ryskamp, Joseph Viscomi, and the staff of the John Hay Library (especially Jennifer Lee) helped me to make sense of these discoveries.

Sherman purchased the Europe leaf, Songs 20 and 21, the proof from Thornton’s Virgil, and the Job engravings from the Weyhe Gallery (New York) in 1938 or 1939; in his copy of Weyhe’s Catalogue #81 (December 1938), preserved at Brown, he wrote “Mine” in the margin next to several entries on pp. 11 and 12, and dated the annotations 4 August 1939. (Sherman may have been mistaken in claiming the entry for Europe—see below.) Songs 13 could have come through Weyhe as well, but it is not listed in this catalogue; because it has been trimmed differently and bound separately, it may have been acquired at another time. According to Blake Books, the Weyhe Gallery probably broke up copy o of Songs, which once contained at least 17 plates from both Innocence and Experience (Bentley 429). Bentley’s forthcoming Blake Books Supplement will describe the fates of eight additional pages from Songs o.

begin page 95 | ↑ back to topEurope c

The leaf containing two plates from Europe (accession number KPR 142) is much more important from a scholarly perspective than the posthumous pages from Songs and the other restrikes. The Europe leaf was matted for the exhibition at Brown, but it is now loose in the portfolio that also contains the Job engravings. Its left edge (recto) is irregular where it has been cut from an earlier binding: the leaf now measures 22.3 centimeters across the top, 22.7 across the bottom, and is 31.2 centimeters high. It bears various unidentified dealers’ or collectors’ annotations in pencil (recto, top left: “18,” lower left: “Rx,” and “Europe page 6,” bottom margin: “This is the one in the [?]”; verso, top left: “19,” lower left: “Europe page 16”), as well as the number 38, written in ink at upper right in the recto. The leaf came from what is called copy c of Europe, which was never an actual copy of the book but the uncoordinated plates from Europe that were once included in a volume of miscellaneous Blakeana assembled by George A. Smith in the mid-nineteenth century. This collection is described in Blake Books under “The Order in which the Songs of Innocence and Experience ought to be paged” (337-41).

The leaf from Europe c at Brown is well printed on heavy wove paper, without watermarks, in two different colors of ink: a slightly brownish gray for plate 11 (illus. 1) and a grayish blue for plate 17 (illus. 2), with slight vestiges of black ink appearing along the edges of a few relief areas on both sides. Plate 11 probably would be darker but still gray if printed more heavily, and 17 would be decidedly blue, but not so bright a blue as the ink on plate 17 in copy B (on inks, see Viscomi 95). Both plates are printed squarely, and appear to have been carefully registered to each other in the recto/verso format. The plate border (the relief line around the edges of the plate created by the strips of wax used to hold acid on the plate during etching) has been wiped before printing on plate 17 and on the upper left corner of 11, as Blake often did in printing relief plates before 1795. This must be a 1794 impression because plate 17 is in the first of three states: line 32 reads “She ceas’d, and all went forth to sport,” rather than “She ceas’d, for All were forth at sport,” and line 35 still ends “and the angel trumpet blew”; this phrase was gouged out of the plate in later states. The leaf at Brown must therefore have been printed by Blake, even if he never finished it or assembled into a book the pages known as Europe c.

The discovery of this leaf solves some old puzzles and raises some new questions. A leaf of a slightly different size but bearing plates 11 and 17 on recto and verso that was formerly in the collection of Charles Ryskamp (sold in July 1994 by a Connecticut dealer to Robert N. Essick) has been confused with the one just discovered at Brown. In Blake Books Bentley traced the Ryskamp/Essick leaf from George A. Smith to Quaritch to Muir to Macgeorge to George C. Smith to Weyhe, after which it disappears until sold by “Allen of New York” in about 1964 to Ryskamp (Bentley 339-41). Sherman’s annotation in the Weyhe catalogue, noted above, and the closer fit of the Brown leaf to the fuller description in the 1938 Parke-Bernet catalogue of the George C. Smith sale (quoted below), led me at first to believe that this entire provenance should be assigned to the leaf at Brown, leaving the Ryskamp/Essick leaf an orphan. But the entry in the Weyhe catalogue that was claimed by Sherman is more likely a description of the Ryskamp/Essick leaf, which is printed in green on both sides, than of the leaf at Brown, which is unmistakably gray and blue: begin page 96 | ↑ back to top

125. “ARISE O RINTRAH . . .” Plate 6 of “Europe a Prophecy”, almost full page composition of a kneeling woman clasping a patriarch with outstretched arms, superb in design, etched on copper and printed in relief as a woodcut in green ink; and on the reverse page 16 of the same book, “Ethinthus Queen [sic] of Waters”, also printed in green ink, MacGeorge Coll., exceedingly scarce 125.00 (Weyhe 11).

Thus the Ryskamp/Essick leaf is probably first recorded in this Weyhe entry; the leaf is now closely trimmed, and does not bear an ink page number like those George A. Smith wrote on the items bound with “The Order of the ‘Songs,’” though it might have been part of that collection or the later Macgeorge collection, as claimed in the Weyhe catalogue. The leaf at Brown does have an ink page number, 38, that corresponds to an appropriate place in the collected volume (which place had been tentatively assigned to an untraced impression of Europe 15; see Bentley 338). Both the Ryskamp/Essick and the Brown leaves must have come through Weyhe at some point; the Brown leaf was probably purchased from Weyhe in 1939 (Sherman must have recalled from whom he bought it and when, even if he didn’t closely check the ink color in the catalogue entry). The Brown leaf is certainly begin page 97 | ↑ back to top the one sold to Weyhe in 1938, as described in the Parke-Bernet catalogue:

32. [Blake]. Five Plates for “Europe, a Prophecy”. 5 plates on 3 leaves printed in gray, grayish-blue, sepia, and in black.

These are apparently proofs.

(1) Begins “Arise O Rintrah”. Printed in gray. Measures 12 5/16 by 8 7/8 inches [31.3 by 22.5 cm].

(2) Begins “Ethinthus queen of waters”. Printed in grayish-blue on the reverse of the preceding plate (Parke-Bernet 17).

These colors are correct for the Brown leaf, as are the dimensions; the Ryskamp/Essick leaf is much smaller: 25.6 cm high and 19.3 cm wide.

The pairing of plates 11 and 17 on these leaves could have been an artifact of experimental proof-printing in which, to save paper, Blake grabbed at random an unused impression of plate 11 and proofed plate 17 on the other side to see how the latter looked. Perhaps something like that sequence happened a decade or two later with those plates of Europe that have plates from Jerusalem printed on the other side (Bentley 144).1↤ 1 Unused impressions of plate 11 might be expected to exist, for the extensive white-line engraving (executed with a burin after etching) that delineates the clouds on that plate might have called for regular proofing to check progress. But in fact plate 11 on the Brown leaf is in exactly the same state as all other surviving impressions—so it probably didn’t become scrap paper because Blake was dissatisfied with the design or the text on the copperplate. Further, plate 11 printed at least as well as in pages that were used in Europe, so it wouldn’t have been rejected for that reason. But the conjunction of plates 11 and 17 on recto and verso may be something more than an ordinary consequence of proof-printing on salvaged paper. The pairing may instead be a vestige of an early version of the book that was superseded rather than a mere accident. There are at least three additional 11/17 pairs, none of them in copies of Europe that are generally regarded as complete: in copy a, at the British Museum; in copy b, at the Morgan Library; and another leaf from Europe c at the Newberry Library (Bentley 144). The mere existence of five such pairs suggests that they were created deliberately rather than randomly.2↤ 2 It is also possible that Blake and/or his wife became confused in trying to print pages in recto/verso format, the arrangement used in several early copies. Losing one’s place would be easy in the case of a book with no printed page numbers and few catchwords. Viscomi shows in Blake and the Idea of the Book that Blake usually produced illuminated books in small editions, so he and Catherine could have printed plate 17 several times on the back of good impressions of plate 11 when they meant to print plate 12, and then put these leaves aside when they discovered the error. But plate 17 is in at least three different colors in these 11/17 pairs, which makes a single printing disaster a little less likely. Further, Blake wiped the plate borders before printing the Ryskamp/Essick, Newberry and Brown 11/17 leaves (and perhaps the others as well), a procedure that would not have been necessary for most workshop proofs, such as those created to check the progress of a design or to monitor the adjustment of the press.

Evidence in the text confirms that the leaf at Brown and its 11/17 cousins, some of which have been modified extensively in various ways, mark phases in the transition from one version of Europe, probably a shorter one, to the version that he produced as finished copies in several configurations. Andrew Lincoln noticed in 1978 that copy a, the “incomplete” uncolored copy in the British Museum (with an 11/17 pair), could actually constitute an “early version” of Europe that lacked the episode on plates 12-16. It is not hard to envision the material on plate 17 following that on 11, for both consist of roughly parallel invocations of her offspring by Enitharmon. (For those using Erdman’s revised edition or The Illuminated Blake, plates 11 and 17 in Bentley’s pagination correspond with Erdman’s plates 8 and 14.) As Lincoln suggested, the narrative on plates 12-16 must be an interpolation, though it could have been assembled in part from plates that were originally elsewhere in Europe (see also Larrissy, who describes connections with America). Plates 12-16 encompass an independently coherent description of Enitharmon’s 1800-year sleep, beginning abruptly at the top of plate 12 and ending on plate 16, when she wakes up and returns to her invocations. It is true that Ethinthus, addressed at the beginning of 17, is first mentioned in the last four lines of 16, but as Viscomi notes in correspondence, the 11 lines at the end of this plate can be seen as a transitional device to reintroduce the interrupted song of Enitharmon.

Blake apparently made the textual revisions on plates 17 and 18, the mechanics of which are described by Viscomi (278-79), in order to accommodate the new narrative created by the interpolation. He modified line 17:32 from “She ceas’d, and all went forth to sport,” the original printed text in the 11/17 pairs, to “She ceas’d, for All were forth at sport” in the finished copies because, once plates 12-16 had been added, the party to which Enitharmon was calling her sons and daughters had already been going on without her for 1800 begin page 98 | ↑ back to top

Europe as a whole generated an unusual number of surviving “proof” pages and variant states (Viscomi 276-79); each of these may have its own story to tell. Some of these pages appear to have been rejected preliminaries, some transitional states, and others private afterthoughts, as David Erdman regards the variant title pages (397). We certainly have an extraordinary wealth of complex evidence to work with: the other 11/17 pairs, especially those with modifications in ink and by erasure; other variant pages; additional recto/verso pairs of other plates; inferences that can be drawn from the order in which Blake used the backs of the America copperplates to make the Europe copperplates (see Bentley 145 and Viscomi 413n3); offsets on “proofs” and other pages; and more. It is possible that the version of Europe in which 17 followed 11 was merely one of several orders with which Blake experimented. Yet because there are five 11/17 pairs, Blake probably had settled on a complete ur-Europe (perhaps corresponding to copy a, as Lincoln suggests) that he regarded as ready to publish, and he began to do so. Then he decided to make radical changes, one consequence of which is the extraordinary number of unused plates from this illuminated book. Scholars attempting to sort out the composition process of Europe must carefully consider the potential significance of all the “proof” leaves, especially the recto/verso pairs, but even a study of the further implications of the 11/17 pairs alone will depend on a much more thorough survey of them than I have done.

Songs o

All three plates from the posthumous Songs o at Brown are printed in the orange-brown ink that Bentley describes as having been used for Songs 39, copy o, in his collection (Bentley 371). Songs 13 and 20 are underinked, and all three plates were printed with their borders. The poor inking and the unwiped borders are characteristic of posthumous pulls by Frederick Tatham, as is the fact that the platemark dimensions run about two millimeters larger than those of copies printed by Blake, who dampened the paper before printing to improve ink absorption; it shrank as it dried (Bentley 67). Songs 13 and 20 both show portions of a J WHATMAN watermark that do not include a date, though the paper is probably the same as that of Songs 39, copy o, which has an 1831 Whatman watermark (Bentley 371).

Songs 13 is by itself in blue boards, together with a loose fragment trimmed from the page; the leaf now measures 16.0 by 23.0 centimeters (using width by height as in Blake Books). The fragment measures 18.1 by 2.5 centimeters; the whole leaf begin page 99 | ↑ back to top was therefore almost as wide as Bentley’s Songs 39 from this copy of the book, which measures 18.6 centimeters. The fragment, inscribed in pencil “Page from Blake’s Songs of Innocence Chas Eliot Norton/ SP 40,” identifies one nineteenth-century owner of the whole book. Songs 20 and 21 are bound together in the same kind of blue boards as those containing Songs 13, but the two leaves have been even more severely trimmed, to 11.8 by 20.0 centimeters. They are both inscribed (at the bottom of the leaves, in the same hand as on the scrap from Songs 13), “Blake Songs of Innocence Charles Eliot Norton Collection.” The accession numbers in the Koopman Collection for the Songs pages are KPR 178-80.

Other Blakes

The impression of Blake’s wood engraving XIII from Thornton’s Virgil (illus. 3; accession number KPR 177) is probably what its mount claims it to be, a posthumous impression once owned by Samuel Palmer that was taken by Edward Calvert from the blocks when they were owned by John Linnell. The heavily inked print is on thin paper without a visible watermark, trimmed to the very edge of the image at 7.8 by 3.6 centimeters, mounted on a thick card that is only about a millimeter wider all around, then pasted on heavy wove paper and bound in brown boards. An inscription on the original mount by A. H. Palmer, Samuel’s son, has been copied onto the stiff paper on which the print and card are now mounted: “These identical proofs [there is only one now] of Blake’s Philips’s Pastoral (and this mount) were S. Palmer’s constant companions for many years. The proofs were printed by Edward Calvert, at Brixton, for John Linnell. See No. 28, V and A Museum Exhibition Catalogue p. 27. A. H. P.” One might suspect the younger Palmer of mild puffery here. Samuel Palmer also owned (and gave away) at least one impression from the unmutilated blocks made in his presence by Blake himself (Palmer 2: 707-08), and the particular image on Plate XIII contributed less decisively to the Shoreham style than did the pastoral scenes among Blake’s illustrations in this series. But the gracefully distorted dancers here resemble figures that appear in Palmer’s work and that of the other “Ancients” (see Paley), and this print may well have been important to him.

The Job engravings (accession numbers KPR 140 and 141) are good “post-proof” impressions on thin India paper laid into unmarked heavy wove paper; they are probably from the final 1874 issue of 100 copies ordered by John Linnell (Bentley 524). The wove paper of Job 15 measures 33.0 by 45.9 centimeters (India 16.3 by 20.8); Job 20 is 34.3 by 42.5 (India 16.2 by 21.1).

The copy of Chaucers Canterbury Pilgrims (KPR 258) at Brown is sealed in a mat and frame and was not available for close inspection, but it is certainly a fifth state impression on India laid on wove paper, probably a late nineteenth-century Colnaghi restrike (see Essick 85-86). This print is much less heavily inked than the Sessler restrikes of the 1940’s and seems almost gray by comparison; Essick attributes the flatness of Colnaghi restrikes to inadequate cleaning of the plate before printing (85).

WORKS CONSULTED

Bentley, G. E., Jr. Blake Books. Oxford: Clarendon, 1977.

Brown University. The Collections of Brown University. Providence: n.p., 1992.

Erdman, David V. The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake. Newly rev. ed. Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1982.

Erdman, David V. The Illuminated Blake. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1974.

Essick, Robert N. The Separate Plates of William Blake. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1983.

Larrissy, Edward. “Blake’s America: An Early Version?” Notes and Queries 30 (1983): 217-19.

Lincoln, Andrew. “Blake’s ‘Europe’”: An Early Version?” Notes and Queries 25 (1978): 213.

Paley, Morton D. “The Art of ‘The Ancients.’” Huntington Library Quarterly 52 (1989): 97-124.

Palmer, Samuel. The Letters of Samuel Palmer. Ed. Raymond Lister. 2 vols. Oxford: Clarendon, 1974.

Parke-Bernet Galleries. William Blake: The Renowned Collection of First Editions, Original Drawings, Autograph Letters, and an Important Painting in Oils . . . Collected by the Late George C. Smith, Jr. (Catalogue #59). New York, Parke-Bernet, 1938.

Viscomi, Joseph. Blake and the Idea of the Book. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1993.

Victoria and Albert Museum. Catalogue of an Exhibition of Drawings, Etchings and Woodcuts by Samuel Palmer and other Disciples of William Blake. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1926.

Weyhe Gallery. Fine Prints Old and New, Drawings and Sculpture. New York: Weyhe Gallery, 1938.