ARTICLES

Sunshine and Shady Groves: What Blake’s “Little Black Boy” Learned from African Writers

At first glance, the poetic diction, heroic verse and classical allusions characterizing Phillis Wheatley’s 1773 Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral would seem to suggest that her poetry has everything to do with neoclassicism and nothing at all to do with romanticism. Yet a closer examination of Wheatley’s collection reveals its significance not just to the neoclassical tradition from which it derives, or even to the African-American literary tradition which it initiates (Gates x), but also, and quite surprisingly, to a particularly problematic poem of the English romantic tradition. The problematic poem is William Blake’s “The Little Black Boy,” and I will argue that reading this song of innocence alongside Wheatley’s “An Hymn to the Morning,” one of the poems in her 1773 volume, leads to a better understanding of Blake’s child speaker and of the intense irony used to portray his situation.1↤ 1 Harold Bloom calls “The Little Black Boy” “one of the most deliberately misleading and ironic of all Blake’s lyrics” (Blake’s Apocalypse 48) and many of the poem’s other readers recognize irony as its central element. See, for example, Howard Hinkel’s “From Pivotal Idea to Poetic Ideal: Blake’s Theory of Contraries and ‘The Little Black Boy’”; C. N. Manlove’s “Blake’s ‘The Little Black Boy’ and ‘The Fly’”; or, more recently, Alan Richardson’s “Colonialism, Race, and Lyric Irony in Blake’s ‘The Little Black Boy’.” Also arising from the juxtaposition of these two poems is the interesting possibility that Blake had some familiarity with Wheatley’s work in particular, and with eighteenth-century England’s small but notable African literary community in general.2↤ 2 For an introduction to African-English literature of the eighteenth century, see Keith Sandiford’s Measuring the Moment: Strategies of Protest in Eighteenth-Century Afro-English Writing or Paul Edwards’s and David Dabydeen’s anthology of extracts, Black Writers in Britain 1760-1890.

The slave of a wealthy Boston family, Wheatley turned to England with her volume of poetry only after American publishers had rejected it (Mason 5). Yet these circumstances may have helped to establish and sustain her reputation, for upon its publication in London, the volume was widely and enthusiastically reviewed in British periodicals and its author acclaimed in abolitionist documents for years to come.3↤ 3 For excerpts from the reviews, see Mukhtar Ali Isani’s “The British Reception of Wheatley’s Poems on Various Subjects.” References to Wheatley’s work in Thomas Clarkson’s An Essay on the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species, Particularly the African and in numerous issues of the weekly “founded to combat American slavery,” William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator, attest to the poet’s considerable impact on both English and American antislavery writing (Robinson 53).

Any examination of “An Hymn to the Morning” must be preceded by an understanding of Wheatley’s complex situation as a woman who is at once an African, an American, a slave, a Christian and a poet. Wheatley’s poetry has for many years been criticized by readers who see her verse as imitative and her reluctance to clearly condemn the institution of slavery as reprehensible.4↤ 4 As Sondra O’Neale puts it, Wheatley has been “castigated” by “many modern critics of Black American literature” as “an unfeeling woman foolishly immersed in colonial refinements, oblivious to her own status as a slave and to that of her African peers” (“A Slave’s Subtle War: Phillis Wheatley’s Use of Biblical Myth and Symbol” 144). More recent critics have begin page 5 | ↑ back to top begun to point out African elements in Wheatley’s form as well as her use of irony and subtle manipulations of language to censure the society that has enslaved her.5↤ 5 In “Classical Tidings from the Afric Muse: Phillis Wheatley’s Use of Greek and Roman Mythology,” Lucy Hayden suggests that Wheatley may have been “drawing subliminally on the storytelling tradition of her African past” in her poem “Goliath at Gath” (435); and John Shields, in a chapter in African American Writers: Profiles of their Lives and Works from the 1700s to the Present, asserts that both “An Hymn to the Morning” and “An Hymn to the Evening” suggest “the recollection of an African musical setting” (357). Shields, along with Mukhtar Ali Isani, Lynn Matson, William H. Robinson, Jr., Sondra O’Neale, Betsy Erkkila (and others), are amending our understanding of Wheatley by locating points of resistance and rebellion in her language and poetry. They suggest that Wheatley’s poetry must be read with the knowledge that she has been forced to speak “with a double tongue” (Erkkila 205).

Approaching “An Hymn to the Morning” with this knowledge, we find that the speaker

communicates complex feelings about nature, religion, and her role as a poet in imagery

that brings “The Little Black Boy” to mind. “[W]ritten in heroic verse,” though

“embody[ing] the spirit of the hymn,” the poem begins as the speaker proclaims her

intention to celebrate the dawn through her song.6↤ 6 John Shields,

“Phillis Wheatley and Mather Byles,” CLA Journal (1980): 380.

Subsequent page references will appear parenthetically and will be abbreviated

PWMB. In

this first stanza Wheatley calls upon the muses for assistance as she composes her paean

to the rising sun, confidently situating this poem within the classical poetic tradition

of the society which has enslaved her. Her description of the beauty and brilliance of

the awakening morning progresses uneventfully throughout the second stanza, but by the

third stanza a discordant note becomes apparent, as the speaker makes a curious request:

“Ye shady groves, your verdant gloom display/ To shield your poet from the burning

day.”7↤ 7 Phillis Wheatley, The Poems

of Phillis Wheatley, ed. Julian D. Mason, Jr. (Chapel Hill: University of North

Carolina Press, 1989) 74. Subsequent page references will appear parenthetically in

the text. At this point

the poet seems to feel a need

for protection from the very object of her praise. And in the final stanza it becomes

evident that her apprehension was not unwarranted, for here the sun, or “th’illustrious

king of day” has, with his “rising radiance,” driven “the shades away.” Thus, the now

unprotected poet finds that she “feel[s] his fervid beams too strong” and must abruptly

end her composition: “And scarce begun, concludes th’abortive song” (74).8↤ 8 The complete text of Wheatley’s “An

Hymn to the Morning” follows:

Attend my lays, ye ever honour’d nine,

Assist

my labours, and my strains refine;

In smoothest numbers pour the notes

along,

For bright Aurora now demands my song.

Aurora hail, and all

the thousand dies,

Which deck thy progress through the vaulted skies:

The

morn awakes, and wide extends her rays,

On ev’ry leaf the gentle zephyr

plays;

Harmonious lays the feather’d race resume,

Dart the bright eye, and

shake the painted plume.

Ye shady groves, your verdant gloom display

To shield your poet from the burning day:

Calliope awake the sacred lyre,

While thy fair sisters fan the pleasing fire:

The bow’rs, the gales, the

variegated skies

In all their pleasures in my bosom rise.

See in the

east th’illustrious king of day!

His rising radiance drives the shades

away—

But Oh! I feel his fervid beams too strong,

And scarce begun,

concludes th’abortive song. (74)

Clearly, the poet has mixed feelings about her purpose and her potential to accomplish it in this poem. We can only begin to understand the nature of those feelings if we are aware of the traditions which collide in these verses. The poem was certainly meant to be read by its original white English and American audiences as a melding of classicism and Christianity, in which the Greek gods of the sun and the dawn are celebrated at the same time that Christianity’s God and His Son are praised and glorified. Subsequent readers have continued to emphasize these elements of Wheatley’s work, as is evident in Julian Mason’s remark that Wheatley’s “mixing of Christian and classical in the many invocations in her poems (as well as in other parts of the poems) reflects the two greatest influences on her work, religion and neoclassicism” (15).

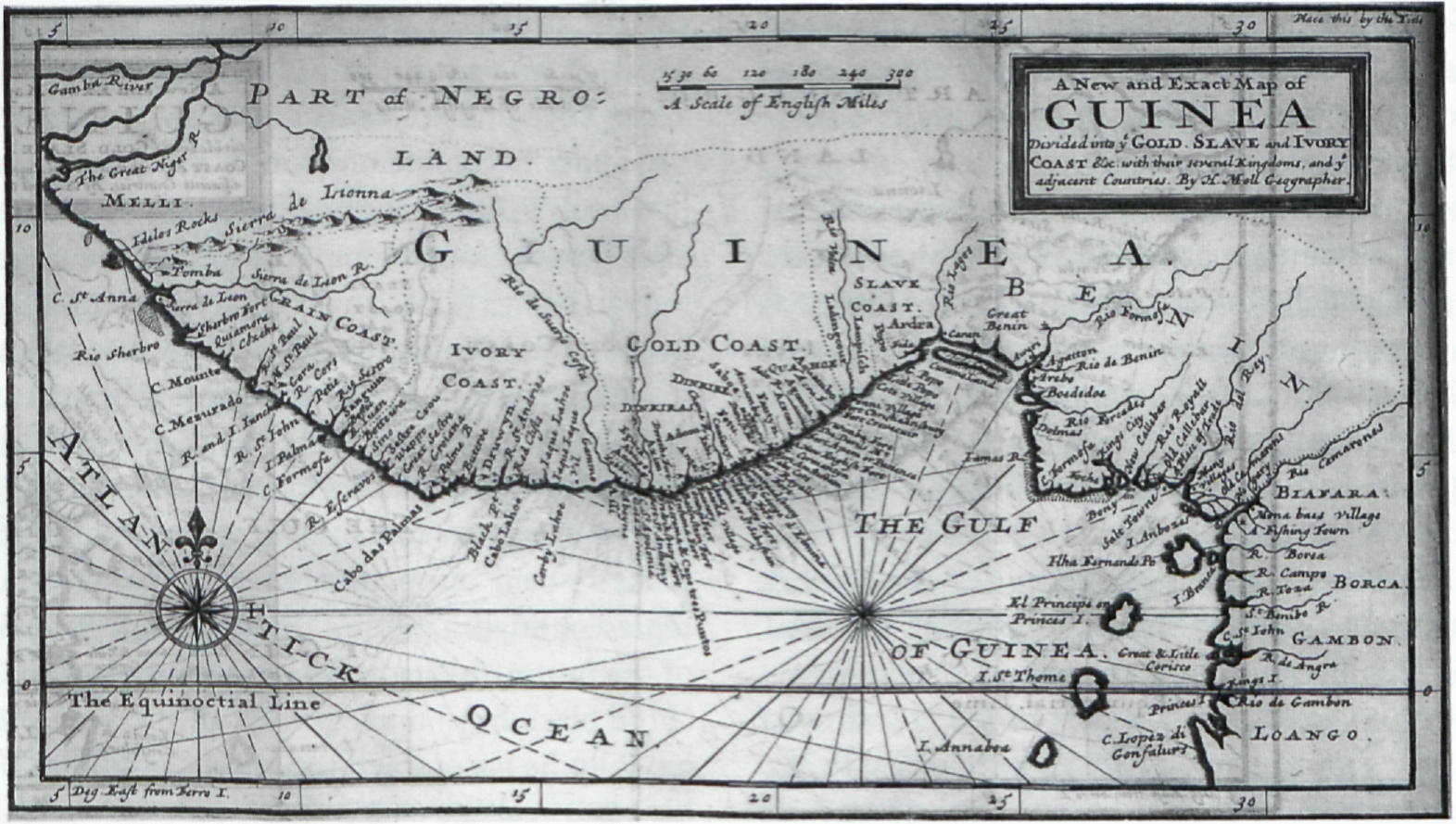

Yet an integrated reading of Wheatley’s work (and of “An Hymn to the Morning” and its sun imagery in particular) requires recognition of cultural influences with non-Western roots. The reader needs to consider, for example, the strong possibility that Wheatley came from an African community in which sun worship was a religious practice, for Wheatley’s first biographer claimed that the poet could remember only one thing about her life in Africa, and that was that every day her mother “poured out water before the sun at his rising” (Odell 10-11). Because Wheatley was kidnapped and brought to America when she was only seven or eight years old, there is no way to be certain of either her place of birth or her native religious traditions, although it has been suggested that “she was very likely of the Fulani people in the Gambia region of West Africa” and that the ritual she remembered may have been a “complex, syncretized version of Islam and solar worship,” as “Islam had long before penetrated into the Gambia region.”9↤ 9 John Shields, “Phillis Wheatley,” African American Writers: Profiles in their Lives and Works, 356. Subsequent page references will appear parenthetically and will be abbreviated AAW. In any case, Wheatley’s intense preoccupation with the sun in this begin page 6 | ↑ back to top poem and others10↤ 10 Shields writes that “solar imagery constitutes the dominant image pattern in [Wheatley’s] poetry” (AAW 356.) certainly can be traced to African origins11↤ 11 In a study of African traditional religions, John S. Mbiti writes that some African cultures perceive God as “‘the Sun’ which beams its light everywhere” and points out that “[a]mong many [African] societies, the sun is considered to be a manifestation of God Himself, and the same word, or its cognate, is used for both” (African Religions and Philosophy 31, 52.) Both Olaudah Equiano and James Gronniosaw also mention sun worship rituals in their narratives (discussed below). and seen as quiet confirmation of a life and religion that were hers before she was enslaved.

Because it is so fraught with contradictions, the sun imagery of “An Hymn to the Morning” calls attention to itself and to the various cultural and religious roles that it is asked to play. Perhaps while Wheatley encourages the reader to consider the cultural convergence in her depiction of this Christian/ classical/African sun, she concurrently questions the role that the sun in its Christian manifestation has played in her own life. We would certainly expect a slave carried to America and converted to the religion of her captors to have doubts about that religion, and of course the only way for her to communicate those doubts would be to cloak them in conventionality. Thus, the tension that exists between the poet’s glorification of the sun and her discomfort when exposed to its “fervid beams” may be the result of Wheatley’s ironic attitude towards her subject: while ostensibly praising her Christian God, she also implies that His presence in her life has made it impossible for her to fully express her beliefs and emotions, and therefore, to write the kind of poem she envisions.

The speaker’s attempt to seek refuge in a “shady grove” and its “verdant gloom” may also be seen as evidence of Wheatley’s conflicted feelings about Christianity and her abiding interest in the religious traditions she left behind in Africa. For just as the sun in this poem suggests an aspect of the poet’s African past, so too does the shade. As Wheatley was composing her Poems on Various Subjects in colonial America, both England and America were amassing voluminous accounts of the life and land of Africa.12↤ 12 Many of these works are discussed in chap. 8 of P. J. Marshall’s and Glyndwr Williams’ The Great Map of Mankind: British Perceptions of the World in the Age of Enlightenment. Philip Curtin also refers to the genre throughout The Image of Africa, as does William Lloyd James in his dissertation, “The Black Man in English Romantic Literature, 1772-1833.” These geographic/ethnographic reports were sometimes written (or compiled) by those interested in abolitionism, but most often by “slave traders or naval officers involved in protecting the trade”; yet in spite of their glaring flaws and prejudices, they were invaluable to those who wanted at least a glimpse of the continent they were colonizing (Marshall, Williams 228). It seems likely that Wheatley’s lack of information about her homeland and “easy access” to “the three largest libraries in the colonies” (Shields PWMB 389n) would have led her to peruse some of these widely published accounts, and a reference to one of them in a 1774 letter suggests that she was, in fact, familiar with the genre.13↤ 13 In a letter to the “Rev’d Mr. Saml. Hopkins of New Port, Rhode Island,” Wheatley writes that she “observe[s] [his] reference to the Maps of Guinea & Salmon’s Gazetteer, and shall consult them” (Wheatley 208). Thus it appears that Reverend Hopkins has directed her to some information on Africa in one of Thomas Salmon’s popular accounts. Examination of some of these works reinforces this suggestion, for one of the African traditions repeatedly remarked upon concerns the practice of meeting and worshipping in a “shady grove.”

One work typical of this genre is William Smith’s A New Voyage to Guinea, first published in 1744. In his depiction of what was then known to the English as the country of Whydah (also referred to as Fida by the Dutch, and Juda by the French), on the Slave Coast of Africa, Smith writes that “[a]ll who have ever been here, allow this to be one of the most delightful Countries in the World,” in part because of “[t]he great Number and Variety of tall, beautiful and shady Trees, which seem as if planted in fine Groves for ornament” (194). He later recognizes, however, that the groves serve a more than ornamental purpose, when he notes that “[a]lmost every Village has a Grove or publick Place of Worship, to which the principal Inhabitants on a set Day resort to make their Offerings, &c” (214).

Thomas Salmon devotes the 27th volume of his encyclopedic Modern History; or the Present State of All Nations (1735) to an examination of Africa, and in so doing, also notes the importance of public shady groves in various African societies. In a discussion of the Congo, for example, he writes that

[as] to the Towns belonging to the Negroes, most of them consist of a few Huts, built with Clay and Reeds, in an irregular manner; and as every Tribe or Clan has its particular King or Soveraign, his Palace is usually distinguished by a spreading Tree before his Door, under which he sits and converses, or administers Justice to his Subjects. But I perceive most of their Towns are in or near a Grove of Trees; for our Sailors always conclude, there is a Negroe Town, wherever they observe a Tuft of Trees upon the Coast. (160)As Salmon goes on to discuss other areas of Africa, he, like Smith, pays particular attention to Whydah in a description he appropriates from Willem Bosman’s firsthand account of the region in A New and Accurate Description of the Coast of Guinea (translated from Dutch into English in 1705). He writes that Bosman’s inquiry into the religion of this society revealed that along with serpents and the sea, the natives of this land show reverence for trees and groves:

The next Things the Fidaians pay Divine Honours to, are fine lofty Trees and Groves. To these they apply in their Sickness, or on any private Misfortune; and I begin page 7 | ↑ back to top ought to have taken Notice, that all the Serpents Temples are in some Grove, or under some spreading Tree. (228)

Salmon’s appropriation of Bosman’s text is not unusual in this genre, for many writing these early accounts of Africa incorporate entire paragraphs and even pages from the works of their predecessors. This is especially true in the case of Anthony Benezet’s Some Historical Account of Guinea, an abolitionist text first published in 1771, for Benezet’s attempt to establish the spiritual potential of Africans is partially based on passages taken directly from both William Smith and Bosman, and these happen to be the passages portraying the religious practices of the Whydah blacks, which, of course, include worshipping in a shady grove (23-28).

Although we must read eighteenth century travel accounts of Africa with caution, remembering that “travellers with closed minds can tell us little except about themselves” (Achebe, qtd. in Brantlinger 95), the likelihood that Wheatley consulted one or more of the works in this genre nonetheless sheds new light on the “shady grove” of “An Hymn to the Morning.” The image now seems to say less about the burning sun and desire for relief from it and more about Christianity and possible alternatives to it. Unearthing African roots in Wheatley’s “shady grove”14↤ 14 Modern studies of African religions attest to the continuing significance of “shady groves” in many African societies. For example, in a chapter on places and objects of worship, Dominique Zahan writes that “the tree acquires an even greater value when it forms a part of the thickets and groves in which man holds religious meetings,” and claims that “[i]n fact, groves are the most preferred places of worship in African religion” (The Religion, Spirituality, and Thought of Traditional Africa 28). Similarly, in African Religions and Philosophy, John S. Mbiti writes of the importance of trees and groves in the worship practices of many African cultures (73). thus relocates the reader somewhere beyond the poem’s pious, conventional, Christian surface. From this new vantage point, we see Wheatley giving credence to a religious ritual that might have been her own had she not been enslaved, and we recognize the note of bitterness in the poem’s abrupt conclusion where a potentially African shade is driven away by a Christian incarnation of the sun.

Turning to “The Little Black Boy,”15↤ 15 William Blake, The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake, ed. David Erdman, 9. Subsequent references to this edition will cite it as “E,” followed by page number. we find that Blake’s poem brings Wheatley’s to mind, as it too makes the reader aware of irony and bitterness through tensions and contradictions in its depiction of the sun and a “shady grove.” As the child of Blake’s poem relates his story, he brings the reader to “the southern wild” where he was born and tells us of his mother’s religious lessons. We find that she, like Wheatley and her own mother, worships a God which she associates with the sun. Yet it is difficult to discern the true nature of the mother’s relationship to this sun/God because, like Wheatley, she presents Him both as an object of devotion and as an entity from which she and her child need protection. She instructs her little boy to celebrate this God who lives in “the rising sun,” yet at the same time explains that they have been “put on earth a little space/ That [they] may learn to bear the beams of love,” suggesting that these are in fact harsh beams to bear (E 9). At this point, the mother sounds remarkably like the speaker of Wheatley’s poem, as she presents her child with an image of the sun that evokes both Christian and African religiosity while espousing beliefs about God and His association with the sun which clearly contradict each other.

The parallel between the two poems extends as the child quotes his mother as saying that “these black bodies and this sunburnt face / Is but a cloud, and like a shady grove” (E 9). The mother also proclaims that someday, when their “souls have learn’d the heat to bear,” she and her son will be called “out from the grove” by the loving voice of God (E 9). Determining whether or not Blake is aware of the religious implications of trees and groves for an African writer such as Wheatley is less important than noticing that the relationship he establishes between the image of a “shady grove” and an African sense of self and blackness duplicates the one developed in “An Hymn to the Morning.” In both poems the “shady grove” is associated with an African speaker’s struggle to construct an identity (either poetic or personal), and in both poems the image of the protective grove is set up in opposition to the sun and to Christianity.

The complexity of the images of sun and shade in these two poems continually conducts the reader back to critical questions about Christianity, and more specifically, about the role that Christianity plays in the life of an enslaved African. When we consider that Christian doctrine was deployed both by pro-slavery apologists who argued that African servitude was ordained by God,16↤ 16 Illustrating the pervasive notion that Christianity sanctioned slavery, Daniel Burton (secretary of London’s Society for the Propagation of the Gospel) explains in a 1786 letter to the Quaker abolitionist Anthony Benezet that the society is unwilling to support Benezet’s antislavery efforts because it “cannot condemn the Practice of keeping Slaves as unlawful, finding the contrary very plainly implied in the precepts given by the Apostles, both to Masters and Servants, which last were for the most part Slaves. . .” (qtd. in Winthrop Jordan’s White Over Black 197). For commentary on some of the pseudo-Biblical theories employed by early defenders of the slave trade, see Charles Lyons’ reference to the Hamitic curse in To Wash an Aethiop White (12) and Keith Sandiford’s discussion of the mark of Cain in Measuring the Moment (100). and by abolitionists who asserted that the institution of slavery was incompatible with Christian teachings,17↤ 17 For one discussion of the argument that slaveholding was in violation of the Christian condition, see “Quaker Conscience and Consciousness” in Winthrop Jordan’s White Over Black (271-76). the relevance and importance of these questions become incontrovertible. Thus, Blake’s reformulation of some of the ideas and images of Wheatley’s poem in “The Little Black Boy” may demonstrate begin page 8 | ↑ back to top his struggle to try to provide his own representation of some of the bleak but unavoidable answers to these questions.

Blake’s struggle to come to terms with these questions and answers is reflected in his depiction of the child speaker of his poem. The “little black boy” is clearly confused by the complexity of the religious and social lessons he has been taught, and by his own dual role as a child of Africa and a child of God. Almost all readers of this poem point to the contradictory nature of the boy’s reasoning: he looks to God for love and protection and yet needs protection from Him; he sees his blackness as a sign that he is “bereav’d of light” (E 9) and as a gift from God; and he believes that when he goes to Heaven, he and the white English boy will both shed their cloud-bodies, and thus achieve some kind of equality, and yet still envisions himself serving the white child, “shad[ing] him from the heat” and “stand[ing] and strok[ing] his silver hair” (E 9).

Some readers of the poem see the child’s “fractured theology” (Macdonald 168) as evidence that he has mingled the religion his mother taught him with the Christianity he was exposed to through missionaries or English Sunday schools in order to “produc[e] a self-affirming discourse of his own” (Richardson 243). While it is difficult to extricate the separate strands of religion and culture here, I think that it is safe to say that there is little of a self-affirming nature in the tensions and contradictions that comprise the resulting religious views of “the little black boy.” Like Wheatley, he has clearly learned that the spiritual teachings of his homeland are considered at best insufficient, and at worst, mere superstition by the society he now lives in. And, like Wheatley, he has learned that in order to be tolerated by this society, he is expected to embrace Christianity, but not to expect too much out of Christianity in return. Thus, as the little boy of this poem grapples with the religions of his past and his present, Blake suggests that confusion, contradictions, and irony are the necessary results of Christianity’s involvement in Africa and the slave trade.

Blake does, however, provide the reader of “The Little Black Boy” with more than a bleak example of Christianity’s impact on Africa and Africans. In the language and images that his poem shares with Wheatley’s, Blake attests to the significance of beliefs and rituals with African origins and thus offers a revised reading of religion to eighteenth-century England. While recognizing, as one modern writer on Africa puts it, that “African traditions are no more homogeneous than those of any other continent” (Hountondji, qtd. in Appiah 95), we can nonetheless see that Blake’s song of innocence, although obviously limited by its historical situation, presents a picture of traditional African belief systems that is both accepting and appreciative of their differences from English Christian creeds.18↤ 18 The possibility that Blake would see African religion from this enlightened point of view is not all that surprising when we consider Blake’s “studious and respectful” attitude to the teachings of Emmanuel Swedenborg throughout the 1780s and some of the specifics of the Swedenborgians’ involvement with Africa (Paley 64). Morton Paley tells us that the Swedenborgians were ardent abolitionists and that “Swedenborg taught that the inhabitants of the interior of Africa had preserved a direct intuition of God” (65). For more on the Swedenborgian antislavery campaign (including the Sierra Leone repatriation plan), see Paley’s “‘A New Heaven is Begun’: William Blake and Swedenborgianism.” This accepting and

Blake’s portrait of childhood in Africa, for example, reminds Paul Edwards of James Albert Gronniosaw’s slave narrative, published in at least four editions in England and America from the 1770s through the 1790s. Edwards suggests begin page 9 | ↑ back to top

In any case, the story told by “the little black boy” of Blake’s poem bears an uncanny resemblance to the story Gronniosaw tells of his own childhood. Gronniosaw writes of a conversation he once had with his mother in Africa about the author of creation and reports that when he “raised [his] hands toward heaven,” and asked “who lived there,” he was “much dissatisfied when she told [him] sun, moon, and stars, being persuaded in [his] own mind that there must be some superior Power” (3). Gronniosaw then remarks that the members of his village often congregated under a number of “large palm tree[s]” for their early morning worship (8). Edwards notes the resemblance of these lines to the second and third stanzas of “The Little Black Boy,” and sums up the relationship by saying that “the two passages share a conversation between mother and child, a sheltering tree, and an identification of the Heavenly Power with the sun, [though] in Gronniosaw it is the child who appears more aware of the Heavenly Power than the mother” (180).20↤ 20 Michael Echeruo recently suggested that Paul Edwards’s article on the possible link between “The Little Black Boy” and Gronniosaw’s Narrative is in need of “some expansion and revision” (51). Echeruo’s argument is that “Thoughts in Exile,” a poem published in 1864 by the Nigerian poet William Cole, “‘challenges’ Blake’s and Gronniosaw’s [poems] in every particular,” especially in its depiction of an African child learning religious lessons underneath his father’s tree (56). In his conclusion, Echeruo suggests that “[i]t would be well worth the effort to identify other instances of this habit of ‘theologizing under a tree’ in written and oral African literature and determine the rhetorical uses to which the topos is variously put” (“Theologizing ‘Underneath the Tree’: An African Topos in Ukawsaw Gronniosaw, William Blake, and William Cole” 56).

Once again encountering the tradition of worshipping the sun from the protective covering of a “shady grove,” we find that Blake’s poem and Gronniosaw’s narrative share more than the specifics of plot outlined by Edwards. Gronniosaw unmistakably establishes the tree and the shade it provides as emblems of African religion, for his initial image of the tree is extended later in the narrative when he explains that even after he had been enslaved and converted to Christianity, he continued to pray under a tree, although he had to replace the palm trees of Africa with a “large, remarkably fine” American oak, “about a quarter of a mile from [his first] master’s house” (24). Reading Blake’s poem in the light of Gronniosaw’s Narrative thus reinforces the suggestion that the specific setting of the religious lesson in “The Little Black Boy,” “underneath a tree,” “before the heat of day,” is intended as acknowledgement of the little that Blake could have known of African religious practices (E 9). And because a thorough begin page 10 | ↑ back to top reading of Gronniosaw’s Narrative confirms that tension and irony inevitably accompany the Christian conversion of an enslaved African, we can recognize in this writer one more likely model for Blake’s child speaker.

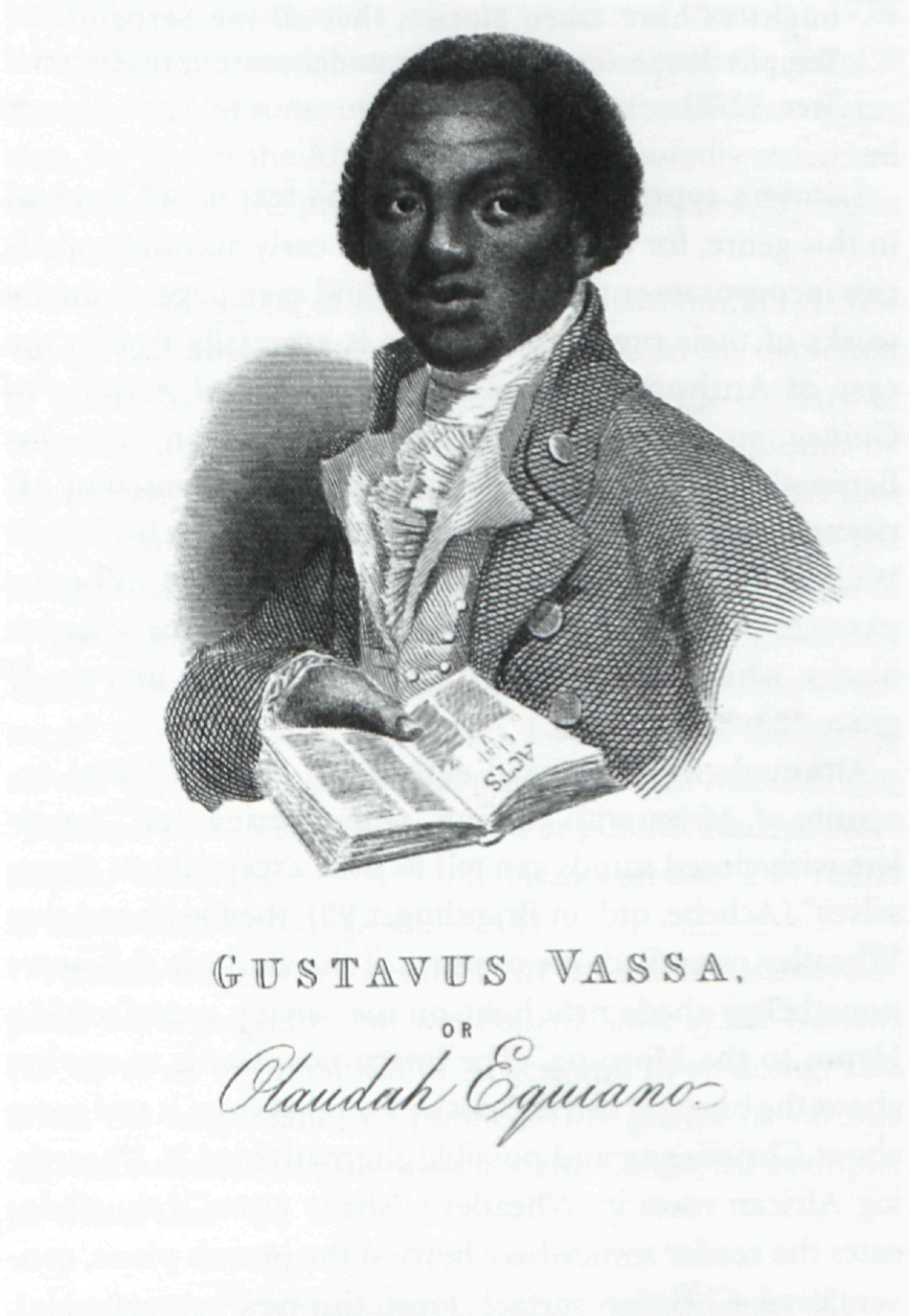

If Blake was indeed familiar with Gronniosaw’s Narrative, it is almost certain that he would also have been aware of the work of Olaudah Equiano, a close friend of Cosway’s servant Cugoano, and probably the most famous of England’s black abolitionists. Equiano’s work, entitled The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano or Gustavus Vassa the African was first published in London in 1789 and went through at least 15 editions by 1834 (Sandiford 10). Along with exposing some of the horrors of slavery, the work depicts the same kind of spiritual struggle as is seen in Wheatley’s poem and Gronniosaw’s Narrative. Equiano appears in one part of the narrative to have completely supplanted his African religious training with Christianity and in another to be revolting against such a distasteful idea. We find him at his most direct when he compares English society to cultures with non-Christian belief systems, and when he presents the reader with an account of his “early life in Eboe” (1). In this account, he describes many of the traditional practices and beliefs with which he was raised, and after considering subjects such as the homes, the food, and the daily occupations of the Eboes, he states that “as to Religion, the natives believe that there is one Creator of all things and that he lives in the sun. . .” (10), thus presenting us with another possible source for the mother’s message to her child in “The Little Black Boy.”

The parallels between Blake’s poem and these African works are valuable in and of themselves, for they awaken us to the fact that enslaved Africans were writing, publishing, and being widely read during the romantic period in England, and thus that they were actively influencing the tide of the abolitionist movement. At the same time, the possibility that this literature may have influenced Blake’s rendering of African experience in “The Little Black Boy” allows a better understanding of why his child speaker voices such paradoxical notions and what Christianity has had to do with the development of these notions.

As Blake’s poem concludes, the “little black boy” offers the reader a vision of his hopes for the future. He sees himself and the little English boy, free from their respective clouds, together in a Heaven in which Christ is depicted as the good shepherd and where “round the tent of God like lambs [they] joy” (E 9). This conclusion has been condemned for its evasion of historical realities and its imperialist implications,21↤ 21 For these assertions, see D.L. Macdonald (“Pre-Romantic and Romantic Abolitionism” 168) and Ngugi wa Thiong’o (Writers in Politics: Essays 20). and the black child’s contented, unquestioning acceptance of this Christian afterlife in which he is the playmate and yet still the servant of the white child seems to substantiate such criticism. And yet the ending of Blake’s antislavery statement is quite similar to that of one of his African contemporaries, Ottobah Cugoano. In Thoughts and Sentiments on the Evil of Slavery, Cugoano concludes his condemnation of the slave trade with three proposals for the people of England. He recommends that after praying for forgiveness for “making merchandize” of human beings (129), and completely abolishing slavery, the British should convert all of the forts and factories used for the slave trade in West Africa into Christian missions or “shepherd’s tents,” where “good shepherds” sent from England will “call the flocks to feed beside them” (133). Juxtaposing these two conclusions makes the ironic element of Blake’s poem more apparent. If Cugoano was unable to represent anything other than an English/Christian vision of the future, then why should we be surprised that Blake’s “little black boy” finds himself in the same situation? Essentially, he has learned the lessons of Phillis Wheatley and his other real-life counterparts only too well.

Works Cited

Appiah, Kwame Anthony. In My Father’s House: Africa in the Philosophy of Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Benezet, Anthony. Some Historical Account of Guinea.... London: 1771, 1788. London: Frank Cass and Co., Ltd., 1968.

Blake, William. The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake. Ed. David Erdman. Garden City, New York: Anchor Press, 1982.

Bloom, Harold. Blake’s Apocalypse. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1963.

Bosman, Willem. A New and Accurate Description of the Coast of Guinea. London, 1705. London: Frank Cass and Co., Ltd, 1967.

Brantlinger, Patrick. “Victorians and Africans: The Genealogy of the Myth of the Dark Continent.” “Race,” Writing and Difference. Ed. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986. 185-222.

Clarkson, Thomas. An Essay on the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species, particularly the African. Philadelphia: Joseph Chambers [?], 1786. Miami, Florida: Mnemosyne Reprinting, 1969.

Cugoano, Ottobah. Thoughts and Sentiments on the Evil and Wicked Traffic of the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species: Humbly Submitted to the Inhabitants of Great Britain by Ottobah Cugoano, a Native of Africa. London, 1787. Ed. Paul Edwards. London: Dawsons of Pall Mall, 1969.

Curtin, Philip D. The Image of Africa: British Ideas and Action, 1780-1850. Vol. I. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, Ltd., 1964.

Echeruo, Michael J.C. “Theologizing ‘Underneath the Tree’: An African Topos in Ukawsaw Gronniosaw, William Blake, and William Cole.” Research in African Literatures 23 begin page 11 | ↑ back to top (1992): 51-58.

Edwards, Paul. “An African Literary Source for Blake’s ‘Little Black Boy’?” Research in African Literatures 21 (1990): 179-81.

Edwards, Paul, and David Dabydeen, eds. Black Writers in Britain 1760-1890. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991.

Equiano, Olaudah. The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African, Written by Himself. 2 vols. London, 1789. Ed. Paul Edwards. London: Dawsons of Pall Mall, 1969.

Erkkila, Betsy. “Revolutionary Women.” Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature 6 (1987): 189-221.

Gates, Henry Louis, Jr. Foreword: “In Her Own Write.” Six Women’s Slave Narratives. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.

Gronniosaw, James Albert Ukawsaw. A Narrative of the Most Remarkable Particulars in the Life of James Albert Ukawsaw Gronniosaw, an African Prince, as Related by Himself. Bath: [c. 1770] and many later editions. Newport, 1774.

Hayden, Lucy. “Classical Tidings from the Afric Muse: Phillis Wheatley’s Use of Greek and Roman Mythology.” CLA Journal 35 (1992): 432-47.

Hinkel, Howard. “From Pivotal Idea to Poetic Ideal: Blake’s Theory of Contraries and ‘The Little Black Boy.’” Papers on Language and Literature 11 (1975): 39-45.

Isani, Mukhtar Ali. “Early Versions of Some Works of Phillis Wheatley.” Early American Literature 14 (1979): 129-35.

Isani, Mukhtar Ali. “The British Reception of Wheatley’s Poems on Various Subjects.” Journal of Negro History 66 (1981): 144-49.

James, William Lloyd. “The Black Man in English Romantic Literature, 1772-1833.” Diss. University of California at Los Angeles, 1977.

Jordan, Winthrop D. White Over Black: American Attitudes Toward the Negro, 1550-1812. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1977.

Lyons, Charles H. To Wash an Aethiop White: British Ideas About Black African Educability 1530-1960. New York: Teachers College Press, 1975.

Macdonald, D.L. “Pre-Romantic and Romantic Abolitionism: Cowper and Blake.” European Romantic Review 4 (1994): 163-82.

Manlove, C.N. “Engineered Innocence: Blake’s ‘The Little Black Boy’ and ‘The Fly.’” Essays in Criticism 27 (1977): 112-21.

Marshall, P.J. and Glyndwr Williams. The Great Map of Mankind: British Perceptions of the World in the Age of Enlightenment. London: J.M. Dent and Sons, 1982.

Mason, Julian D. Introduction. The Poems of Phillis Wheatley. By Phillis Wheatley. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1989.

Matson, Lynn R. “Phillis Wheatley—Soul Sister?” Phylon 33 (1972): 222-30.

Mbiti, John S. African Religions and Philosophy. Oxford: Heinemann International, 1989.

Ngugi wa Thiong’o. Writers in Politics: Essays. Studies in African Literature. London: Heinemann, 1981.

Odell, Margaretta M. Memoir and Poems of Phillis Wheatley, A Native African and a Slave. Boston: G.W. Light, 1834. 2nd ed. Boston: Light and Horton, 1835.

O’Neale, Sondra. “A Slave’s Subtle War: Phillis Wheatley’s Use of Biblical Myth and Symbol.” Early American Literature 21 (1986): 145-65.

Paley, Morton D. “‘A New Heaven is Begun’: William Blake and Swedenborgianism.” Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly 50 (1979): 64-90.

Richardson, Alan. “Colonialism, Race, and Lyric Irony in Blake’s ‘The Little Black Boy.’” Papers on Language and Literature 26 (1990): 233-48.

Robinson, William H., ed. Critical Essays on Phillis Wheatley. Boston: G.K. Hall & Co., 1982.

Salmon, Thomas. Modern History; or the Present State of All Nations.... London: 1735.

Sandiford, Keith A. Measuring the Moment: Strategies of Protest in Eighteenth-Century Afro-English Writing. Selinsgrove: Susquehanna University Press, 1988.

Shields, John C. “Phillis Wheatley.” African American Writers: Profiles of their Lives and Works from the 1700s to the Present. Ed. Valerie Smith, Lea Baechler, and A. Walton Litz. New York: Macmillan, 357-72.

Shields, John C. “Phillis Wheatley and Mather Byles: A Study in Literary Relationship.” CLA Journal 23 (1980): 377-90.

Smith, William. A New Voyage to Guinea. London: 1744.

Stedman, J.G. A Narrative, of a Five Year’s Expedition, Against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam, in Guiana, on the Wild Coast of South America; from the Years 1772 to 1777. London, 1796.

Wheatley, Phillis. The Poems of Phillis Wheatley. Ed. Julian D. Mason. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1989.

Zahan, Dominique. The Religion, Spirituality, and Thought of Traditional Africa. Trans. Kate Ezra and Lawrence M. Martin. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1979.