minute particular

William Blake, Jacob Ilive, and the Book of Jasher

William Blake was, as we know, very interested in research on and speculation about the Bible, including matters such as Hebrew prosody, theories of composition, and the constitution of texts.1↤ 1 See Leslie Tannenbaum, Biblical Tradition in Blake’s Early Prophecies (Princeton: Princeton UP, 1982) 25-54; Morton D. Paley, The Continuing City (Oxford: Clarendon P, 1983) 45-48); and Jerome J. McGann, Social Values and Poetic Acts (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1988) 152-72. He was also, aware of the tradition that there were lost books of the Bible as is shown in plate 12 of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell;2↤ 2 The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake, ed. David V. Erdman, rev. ed. (New York: Doubleday, 1988) 39, hereafter cited as E followed by the page number. as well as by his eagerness to illustrate the Book of Enoch after its publication in 1821.3↤ 3 See Martin Butlin, The Paintings and Drawings of William Blake (New Haven and London: Yale UP, 1981) 1:595. In Swedenborg’s True Christian Religion, Blake would have read that one of these, the Book of Jasher, was extant “amongst the People who live in Great Tartary.”4↤ 4 See my “‘A New Heaven Is Begun’: Blake and Swedenborgianism,” Blake 13 (1979): 80. Blake did not, of course, respond to ideas on such subjects as a scholar but rather as a poet and artist, placing himself in relation to new knowledge by assimilating it. The fact that a work purporting to be the lost book of Jasher (or Jashar) had been published in his own century must have been known to him, especially as it had been produced by a man well known in the printing profession, one whose heterodox religious ideas had some common ground with his own. The fact that this work was widely considered a forgery would hardly have deterred[e] Blake, whose characteristic view was that not the literal fact of production but the inner meaning of a work determines its authenticity. As he wrote in his annotations to Bishop Watson’s Apology for the Bible, “I cannot concieve the Divinity of the <books in the> Bible to consist either in who they were written by or at what time or in the historical evidence which may be all false in the eyes of one man & true in the eyes of another but in the Sentiments & Examples which whether true or Parabolic are Equally useful . . . .” (E 618). In the 1751 Book of Jasher Blake may well have found useful sentiments and examples, as well as a model for the layout of part of his own Bible of Hell, The [First] Book of Urizen.

The Book of Jasher is considered a lost source for parts of other books in which it is named, including Joshua 10-13, begin page 52 | ↑ back to top

2 Samuel 1:18, and the Septuagint version of 1 Kings 8: 53.5↤ 5 “Book of Jashar,” The New Standard Jewish Encyclopedia, ed. Geoffrey Wigoder (New York and Oxford: Facts on File, 7th ed., 1992), s.v. “Jashar” is not a name (as is sometimes supposed) but Hebrew for “the upright one.” In 1751, a printer named Joseph Ilive published what he claimed was an English version by the monk Alcuin: The Book of Jasher, with Testimonies and Notes explanatory of the Text. Ilive himself is a figure of some interest. The son of a printer, he set up a letter-foundry in Aldersgate c. 1730.6↤ 6 H. R. Plomer, in A Dictionary of the Printers and Booksellers Who Were At Work in England[,] Scotland[,] and Ireland from 1726 to 1775 (Oxford: Printed for the Bibliographical Society at the Oxford University Press, 1932 [for 1930]) 136. In 1733 he gave an oration at Joyner’s Hall in Thames Street, pursuant to the will of his late mother, Jane Ilive, who may have been one of the Philadelphian circle around Jane Leade. In this discourse, which he published that same year, he maintained four principal theses: ↤ 7 The Oration Spoke at Joyners hall in Thames Street on Monday, Sept. 24, 1733, t.p.I The Plurality of Worlds

II That this Earth is Hell.

III That the Souls of Men are Apostate Angels. And

IV That the fire which will punish those who shall be confined to this Globe after the Day of Judgment will be immaterial.7

In 1750, addressing his fellow master printers, he said “It may with Great Veracity be affirmed, that there is no Art, Science, or Profession in the World, but what owes its Origin, at least its Progress and present Perfection, to the free Exercise of the Art of Printing,” and he went on to defend “the Liberty of the Press.”8↤ 8 The Speech of Mr. Jacob Ilive to His Brethren the Master-Printers (1750). Prosecuted in 1756 for printing his own Modest Remarks upon the Discourses of the Bishop of begin page 53 | ↑ back to top London (Dr. Sherlock),9↤ 9 The History and Antiquities of Dissenting Churches and Meeting Houses, in London, Westminster, and Southward, 4 vols. (London, 1808) 2: 290-92. Ilive was imprisoned for over a year, during which he took the opportunity to write and publish Reasons offered for the Reformation of the House of Correction in Clerkenwell (1757). We may well imagine that William Blake would have found Ilive’s story of some interest.

The Book of Jasher was recognized as a forgery from the first. The Monthly Review declared it was “a palpable piece of contrivance intended to impose on the credulous, and the ignorant, and to sap the credit of the books of Moses, and blacken the character of Moses himself.”10↤ 10 5 (December 1751): 520. The circumstances of the hoax were recounted in 1778 by Edward Rowe-Mores, in his Dissertation Upon English Typographical Founders and Foundries:

. . . Of the publication we can say from the information of the Only-One who is capable of informing us, because the business was a secret between the Two: Mr. Ilive in the night-time had constantly an Hebr. bible before him (sed. q. de hoc) and cases in his closet. He produced the copy for Jasher, and it was composed in private, and the forms worked off in a private pressroom by these Two after the men of the printing-house had left their work. (65)

That this exposure did not cause The Book of Jasher to disappear entirely from view is shown by the republication of Ilive’s text in 1829.11↤ 11 See Thomas Hartwell Hone, B.D., Bibliographical Notes on the Book of Jasher (London, 1833). S. T. Coleridge, commenting on this edition, thought it was based on one of the “slovenly Eutropius-like Abridgements of the Pentateuch & the books of Joshua & Judges by some ignorant Monk” (The Collected Letters of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, ed. E. L. Griggs [Oxford: Oxford UP, 1956-72] 6: 900). Blake, with his interest in biblical antiquities and his connections with the printing trade, would have had ample opportunity to know the first edition. It is interesting to consider what distinctive features might have interested him most.

In Jasher 3: 19 Abraham is talked out of sacrificing Isaac by Sarah, who says “The holy voice hath not so spoken.” As a result, “Abraham repented him of the evil he purposed to do unto his son: his only son Isaac.” The Egyptians do not pursue the Hebrews into the Red Sea but go home instead (10: 24). Moses is frequently depicted as acting tyrannically.[e] When Miriam opposes his appointing of judges, Moses hides her for seven days until she is released by the demand of the congregation, who prefer her view to his; but after Miriam’s death Moses appoints 70 elders to rule the people (15). In the course of establishing the priesthood of the Levites, Moses has 250 who oppose him killed (22). When Shelomith protests against the laws Aaron gives to the people, he is stoned to death by order of Moses. Achan too

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

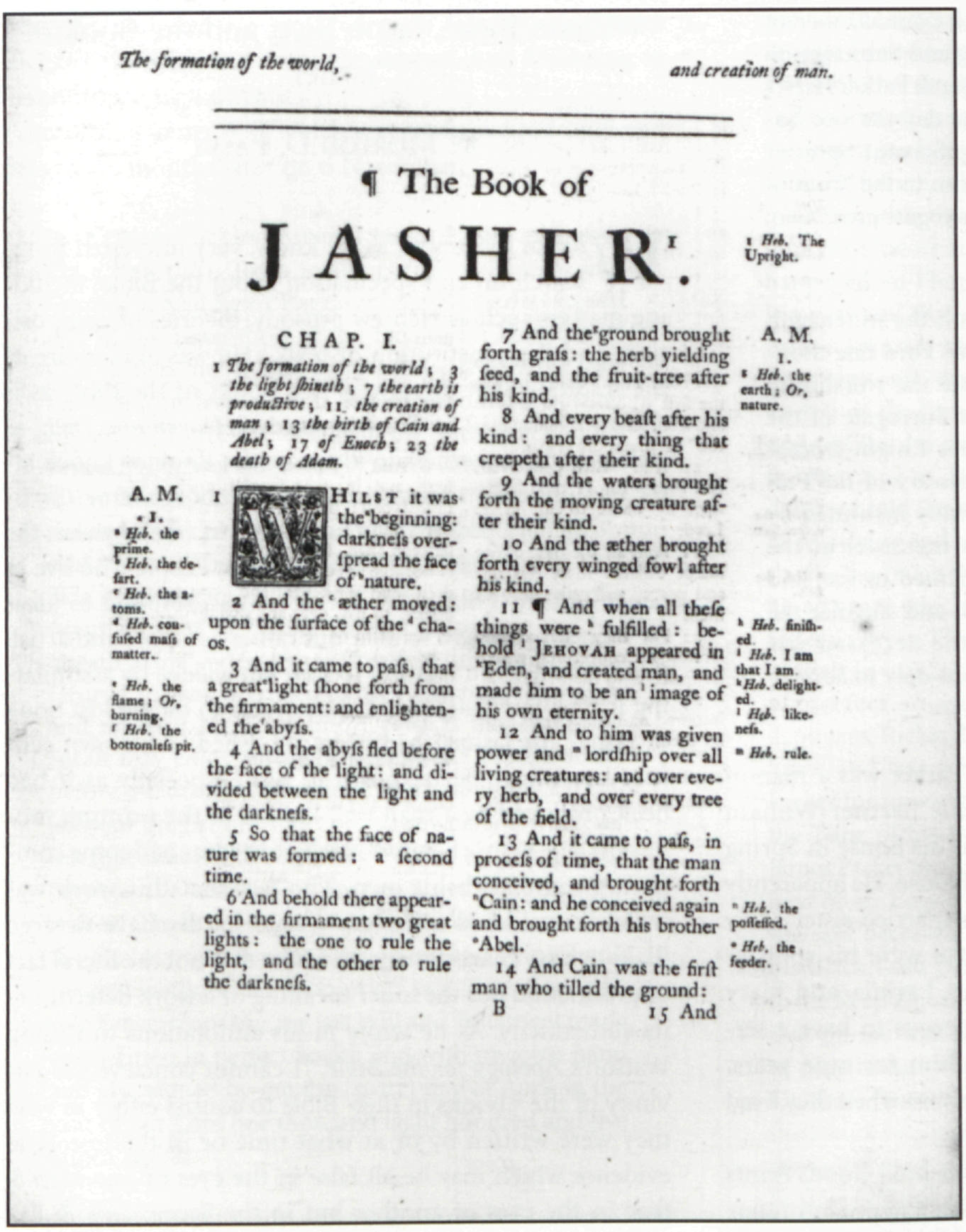

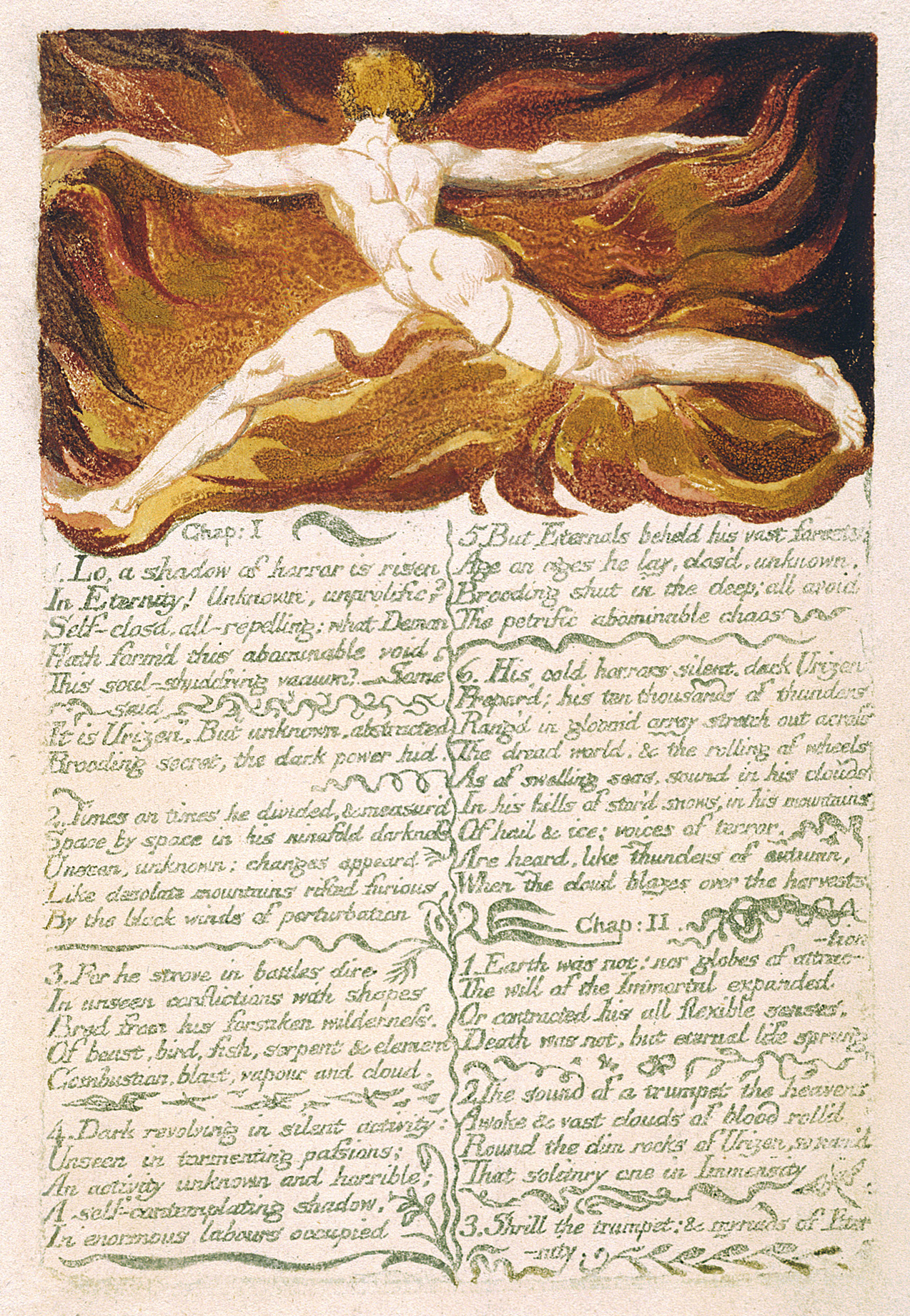

A further point of comparison may be made between the format of The Book of Jasher and that of The [First] Book of Urizen. Both works, as can be seen in the illustrations (illus. 1 and 2), exploit the familiar layout of the Authorized Version and some other English Bibles: a double-columned page divided into chapters and verses. Of course Blake is begin page 54 | ↑ back to top unique in his combination of design and calligraphic text; Ilive’s decorated initial capital is his only gesture in this direction. Nevertheless, both play upon the reader’s experience of opening a conventional Bible, only to present a text subversive of such a Bible. Finally, just as Jasher concludes after its last verse (37: 32) “The End of the Book of Jasher,” Urizen concludes “The End of the [first] book of Urizen” (E 83), both in imitation of colophons in medieval texts. Did Blake recognize Ilive’s private press-room as a forerunner of his own Printing House in Hell?