REVIEW

Veils, Infinity, a Roof, and “One thought” in Contemporary Art

A Note on Four Exhibitions

At the brink of the new millennium, Blake still hasn’t found that large readership in the German-speaking countries which Henry Crabb Robinson had expected to grow so rapidly when drafting the essay he contributed to the Vaterländisches Museum in 1811. Therefore, it comes as a surprise to find that over the past few years Blake’s works have inspired a series of exhibitions by contemporary artists in Austria, Germany, and Switzerland which may warrant a brief report.

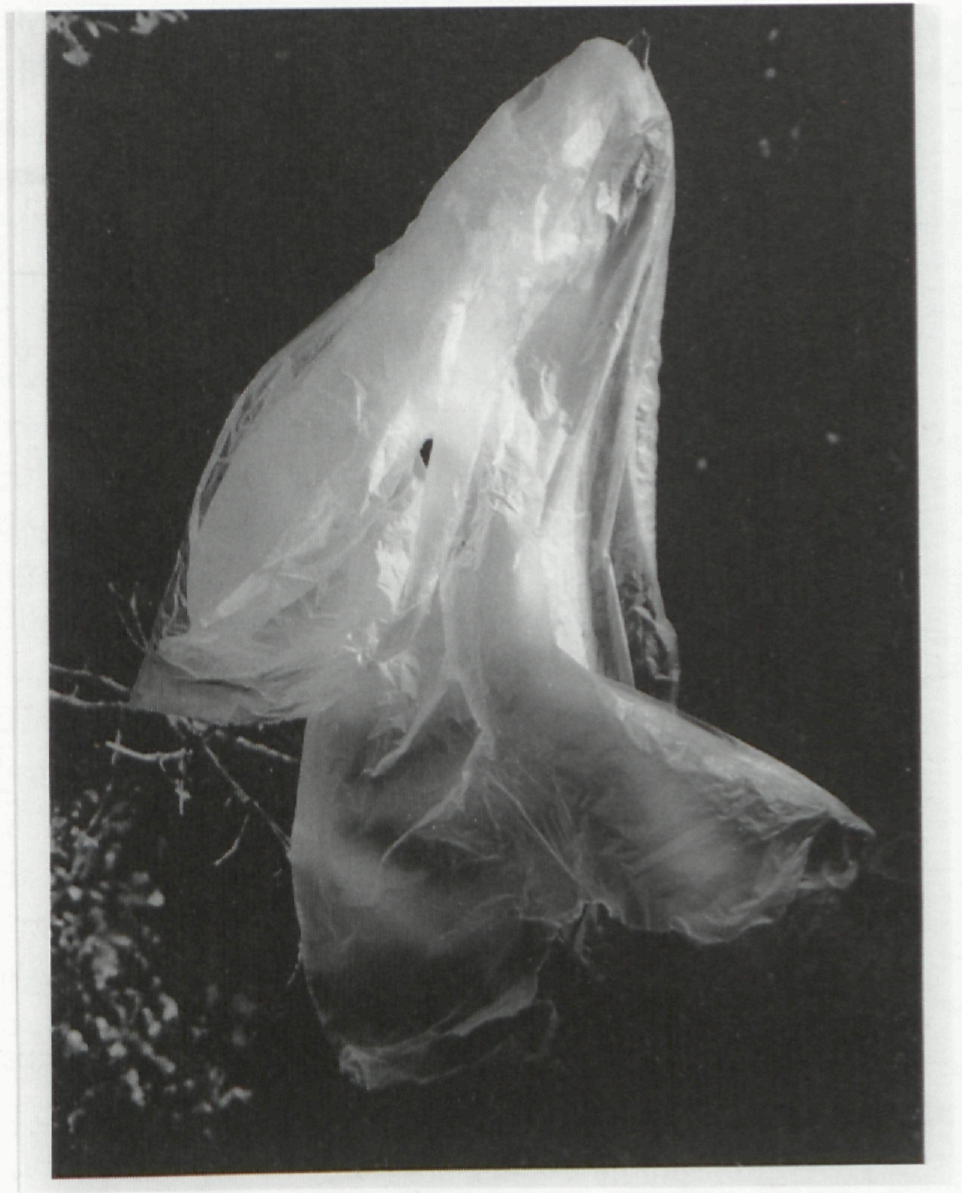

Supposedly, only few of the visitors who came to see Verena Immenhauser’s installation “Beneath the Veil of Vala” at the Berner Galerie in 1988 were fully aware of the Swiss artist’s understanding of the symbol of Vala’s veil/vale and its complex meaning in the poetry and art of William Blake. And yet, anybody ready to engage with the aesthetic experience offered by that installation must have felt the urge to question the relationship between the veil and the veiled, center and circumference, form and formlessness, the cycle of natural growth and decay (reigning in Vala’s vale) and the ideas of stability and of eternity (governing a realm that lies beyond it). Employing soft transparent wrapping foils, Immenhauser created an environment inside the small gallery space which at first sight seemed devoid both of calculated form and all specific content. However, the movements of the visitors quite literally breathed life into the room which was filled with draped “veils” (illus. 1) hanging from the ceiling and hiding the measured dimensions of the walls. The softly whispering and everchanging folds of the thin and shining plastic veils remained entirely abstract in shape, but functioned as an appropriate representation of Vala’s veil of nature. Their rippling-rustling texture lured the sense of touch and the ear, while their utter refusal of all representational concreteness, the complete lack of linear (and optical) solidity, and their shimmering, silvery reflections, irritated and fascinated the eye.

In a sense, this finely tuned metaphor of Vala’s art of seduction seemed related to Marcel Duchamp’s famous “spider-web” installation for the Surrealist exhibition at 451 Madison Avenue in 1942. But it also anticipated such “physical sculptures” as the “Bodycheck” contributed by Flatz to the documenta IX in 1992, or the labyrinth of measured time made from hundreds of clocks, hanging folding rules, begin page 83 | ↑ back to top

For his “1992 Infinite Painting on A Vision of the Last Judgment by William Blake 1808,” shown in Berlin at the Zwinger Galerie, Nikolaus Utermöhlen mounted enlarged photocopies of Blake’s “Vision” on thirteen aluminum panels (200 × 80 cm. each). The reproductions had been produced on a color photocopying machine which was manipulated by the artist so that a sequence of color variations resulted. Each panel (or, as Utermöhlen prefers to call them, each “spectre”) displayed a different layering of the primary colors, blurring and distorting the clarity of Blake’s original watercolor. Its design was thus supplanted with the cool glow of industrial colors which had been heightened by additional hand-tinted patterns and which produced the effect of a giant kaleidoscope. Utermöhlen’s interest in the openness and mechanical “infinity” of possible color variations and in the configurations which can be assembled by grouping the aluminum panels on the gallery walls, produced

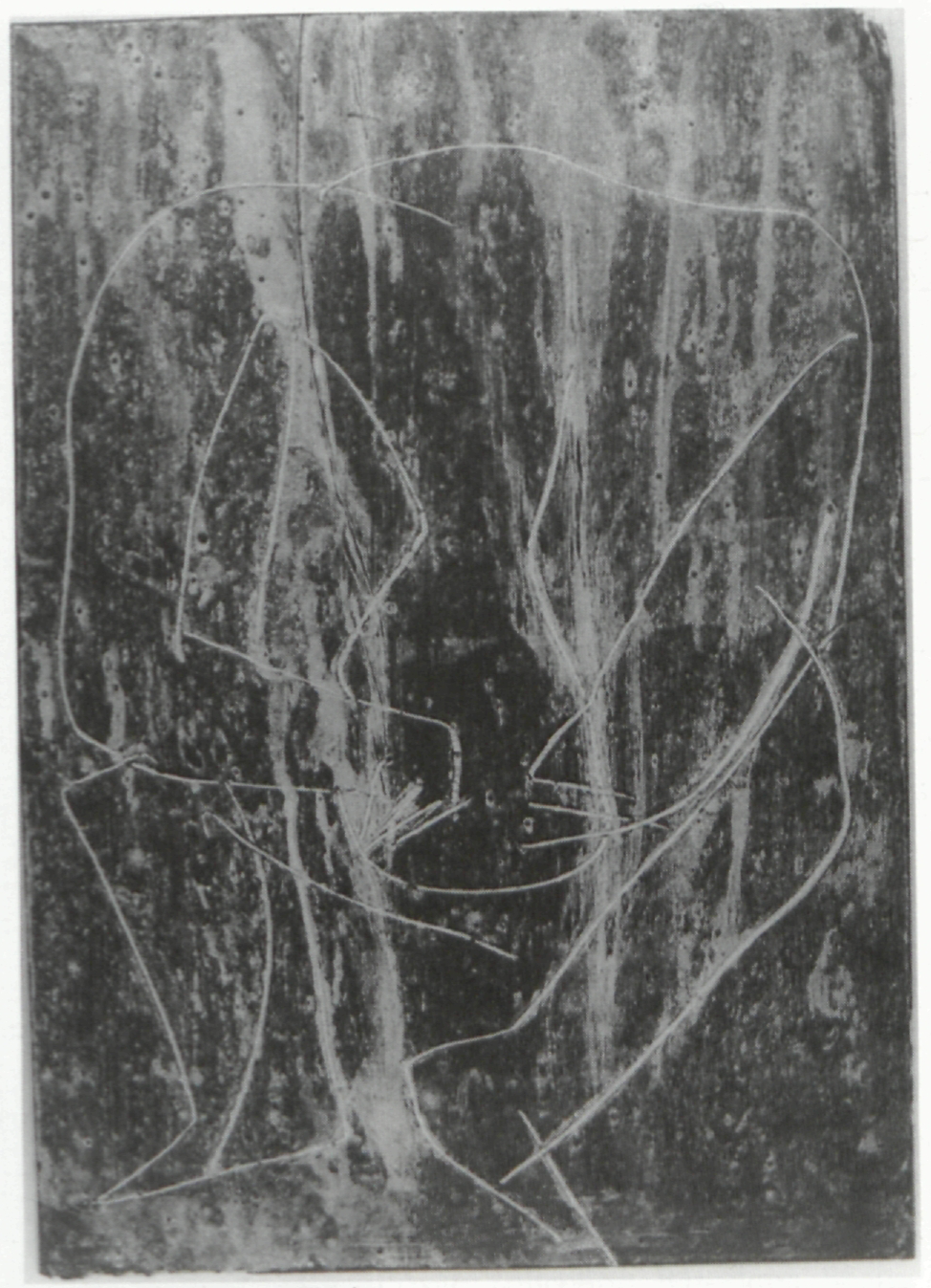

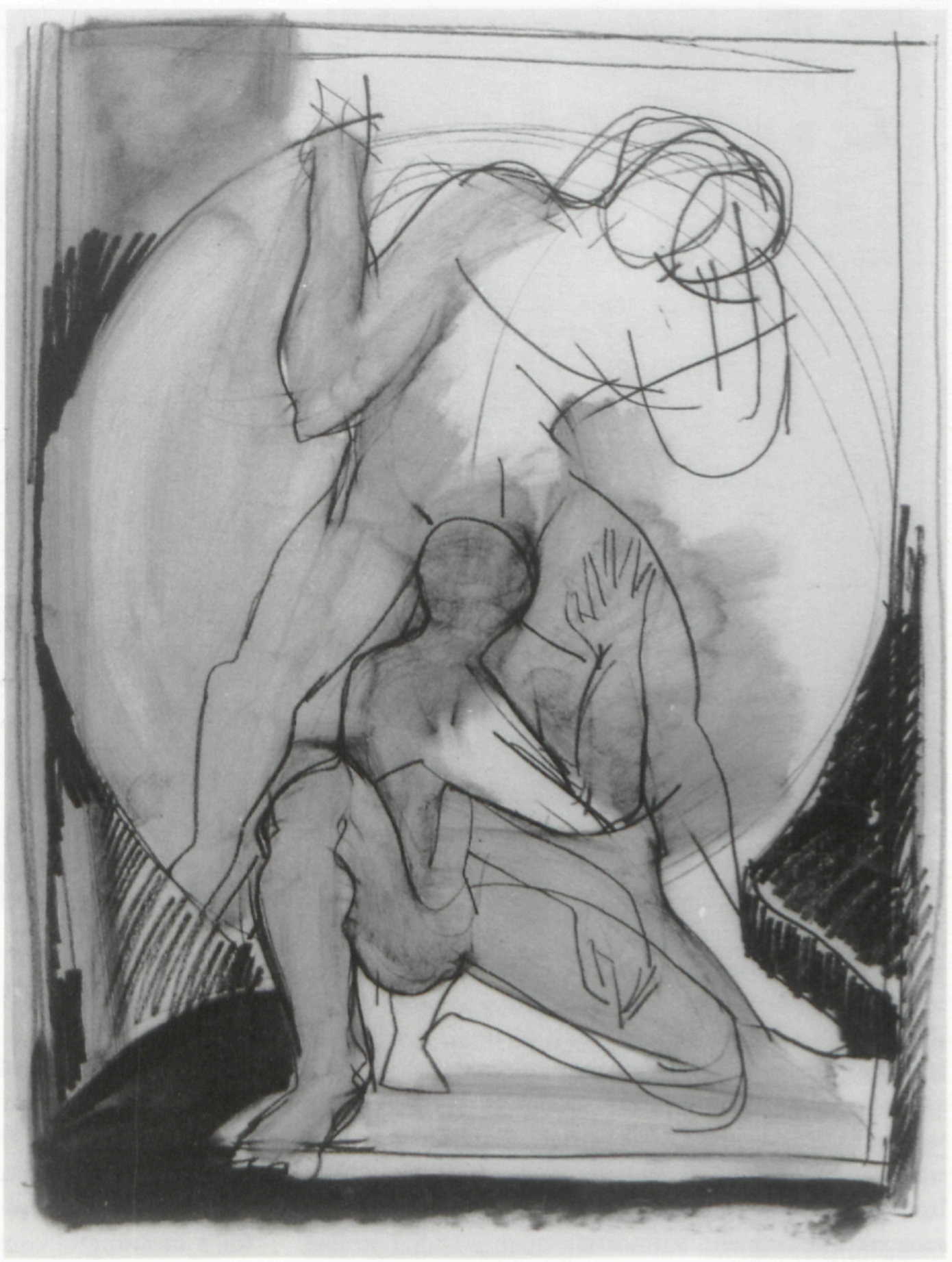

If Utermöhlen’s central concern was that of a formalist, one will have to locate the works of Dieter Löchle at the other end of the spectrum. Under the title “Roof’d in from Eternity,” his Blakean drawings, prints, and paintings were on show at the Tübingen university library in 1995. Almost devoid of color, Löchle’s paintings relied on the simple opposition of darkness and light, created by black, white, begin page 84 | ↑ back to top

Occasionally, when confronted with the symbolic portrait heads and some of the eroticized designs which were included in the show, I felt struck by what seems a curiously straightforward approach to the problems and functions of contemporary visual representation, an approach bordering on the naive. However, Löchle’s linear abbreviations of the “human form divine” generally work well enough as a modern interpretative response to Blake. Because the expressive use of bodily movements in Blake’s designs is perpetuated in Löchle’s pictorial homage, his images seem highly charged with symbolic energy and meaning. And it is here that they provide an antithesis to Utermöhlen’s dominantly formalist concerns. At the same time, the austerity and abstract quality of Löchle’s begin page 85 | ↑ back to top draughtsmanship steer clear of the preoccupation with those “sublime,” “fantastic,” “weird,” and more narrative aspects of the art of Blake and Fuseli which have previously attracted the attention of other Austrian and German artists such as Günter Brus, Alfred Hrdlicka, or Horst Janssen in some of their exhibitions of the 1970s and 1980s.

Löchle’s stylistic choices lead towards a relative independence of his images from their Blakean blueprints. But they draw the viewer’s attention to such characteristics as the white-line technique—first in Löchle’s own prints, drawings, and paintings, but then, on the way out and through the show-cases lined up in the entrance hall, also in Blake’s illuminated prints. In this sense, “Roof’d in from Eternity” was a group exhibition, ideally suited for an academic library. Löchle not only paid homage to Blake, he also invited the visitors to find out for themselves what he had seen in Blake’s colored relief-etchings, and how he had seen it.

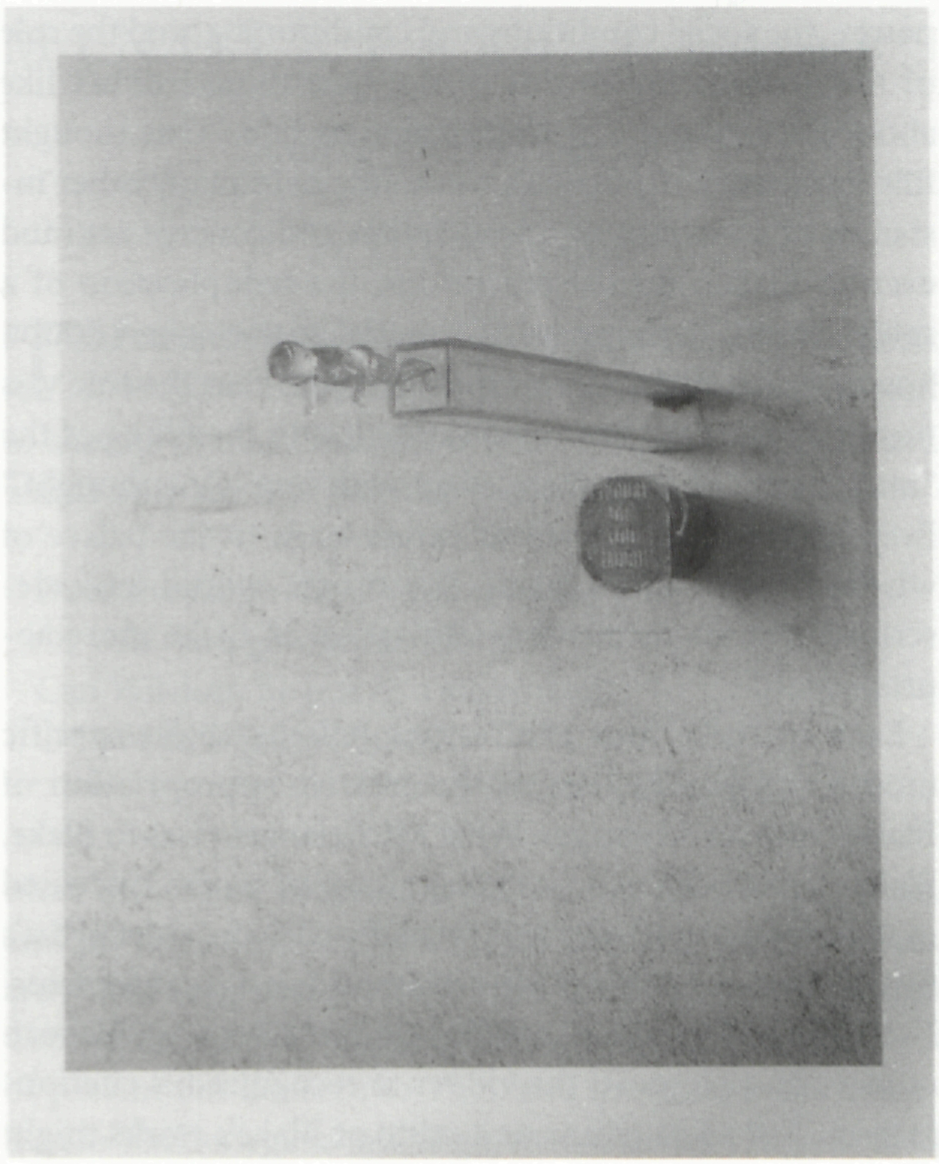

An entirely different and certainly non-didactic approach was chosen for a fourth exhibition which presented a far more radical, avantgardist, and in its own way very exciting use of the raw materials provided by Blake for the making of contemporary art. The first major one-man show in Germany for the Spanish sculptor and installation artist Jaume Plensa was organized by the Städtische Galerie Göppingen in the summer of 1995. Plensa’s art often combines the visual and the verbal in a surprising, some may say an absurd manner. While this relationship of image and text cannot be described as “narrative” in any common sense of the word, it succeeds in making familiar objects seem strange, and it creates “new” and challenging combinations which provoke the senses and the imagination. His recent work exposes the spectator to environments assembled from prosaic objects of the artist’s own everyday life and from inscribed panels, boxes, or cages which are cast in synthetic resin. Together with two other installations, the Göppingen exhibition introduced Plensa’s (as yet unfinished) project on Blake’s “Proverbs of Hell” from The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (illus. 4-5). Similar to Immenhauser’s veils, but adding Blake’s own words in blind-stamped letters on his polyester panels, Plensa’s “Proverbs” provide a highly personal interpretation of Blake, the rich associations of which remain valid (or at least intellectually fascinating) even for an onlooker who is entirely unacquainted with the British poet-artist’s works.

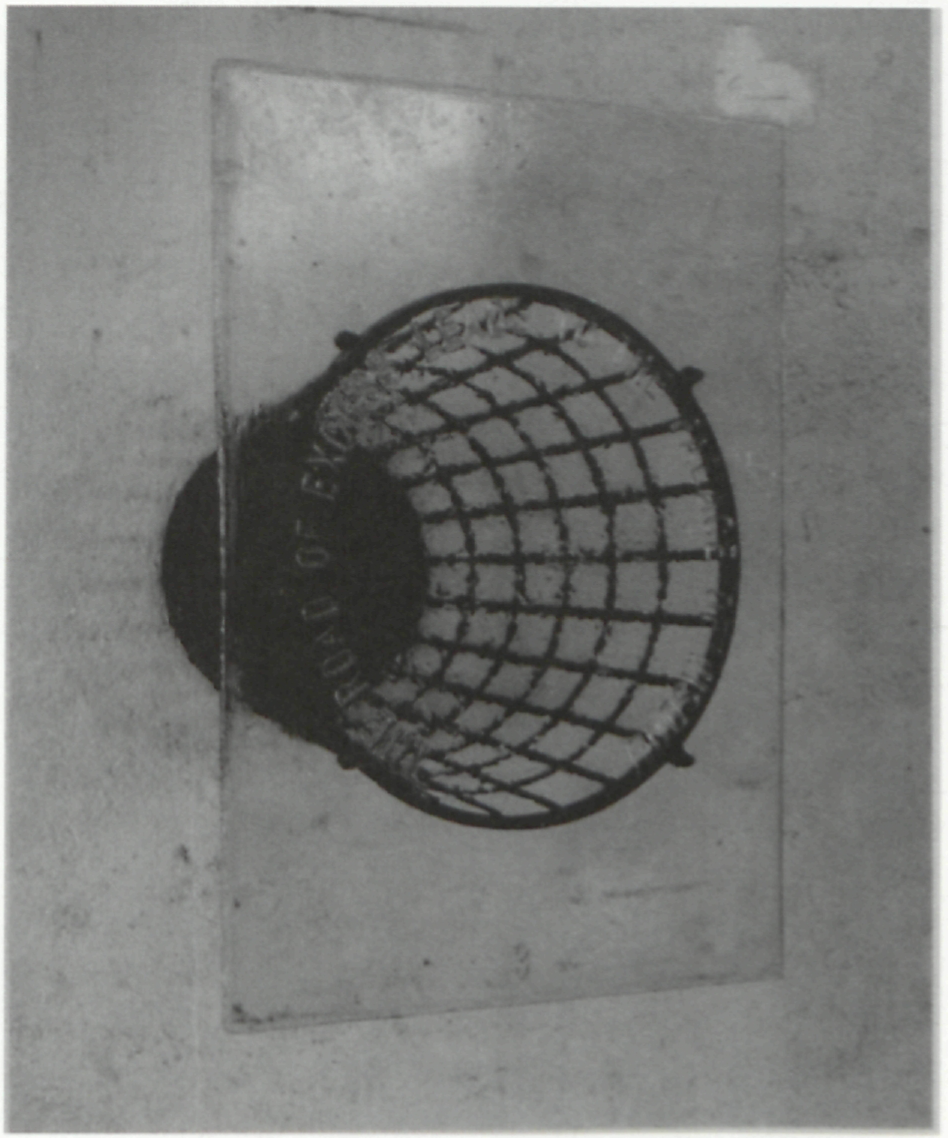

Most of the 1995 “Proverbs” consist of three elements, which are usually mounted at a right angle on the gallery’s walls. The first of these elements is an object from the “hell” of the artist’s studio work, such as a red plastic bucket which had been used in the preparation of the plaster Plensa employs in an early stage of his casting technique, or a cheap metal wastepaper basket which, one imagines, had once been filled with discarded sketches and studies for the artist’s projects. The second element is a pillar, protruding

At the same time the transparent three-dimensional figures prompt us to muse about the relationship between the various elements that have been combined for each of the “Proverbs” and outward reality—to ponder on the practical usefulness of a red plastic bucket, a usefulness which is lost once it is made part of a work of art—to realize that thereby it may, however, achieve a different function, and may as such become useful in a different sense—to contemplate the representation of the human figure in its relation to the abstract stereometry of the pillar-cube it is attached to—and, of course, to think about the continuing relevance of what Blake’s devils have to say concerning the begin page 86 | ↑ back to top nature, the social conditions and conditioning, and the role of the imagination in this world. One thing I didn’t like about the exhibition at Göppingen: its title, “One thought fills immensity.” In Plensa’s work, just as in many other instances of contemporary installation and concept art (and even in Blake), formal repetitions, the reduplication of a specific motif or shape are of essential importance. I doubt, however, that an irony was intended, and that the title was meant to draw the spectator’s attention to the filling of the “immensity” of the gallery space with just “One thought.” Even if it was, “The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom,” and “Enough! or Too much” would have described Plensa’s secular modernization of Blake more appropriately.

Each of these four exhibitions tells us about specific modes and possibilities of the creative appropriation of Blake’s words and images. What Michelangelo was to Blake, Blake is to Löchle who—in the group of works discussed in the present note—literally/visually cites the elder artist’s figural language and/or entire compositional arrangements. Not only is the artist consciously transforming Blakean models, he also wants the viewer to recognize his citations as such. Just as an editor or a critic of Blake’s works might do, Löchle asks for the meaning which Blake’s art may have for an audience separated from its initial production by two centuries. The tension between the historicity of the pictorial inventions and the actuality of their rendering in Löchle’s “cover version,” between the identity of the motifs and the discrepancy of the formal qualities of their representation is exactly where the “meaning” of these paintings and prints from 1994-95 appears to be situated. Löchle’s insistence on visually confronting Blake’s images (by means of the facsimiles included in the exhibition) with his own works demonstrates a historical awareness which in turn allows for linking his art with certain techniques of scholarly interpretation.

If Löchle’s art is inspired by the “historical approach,” Immenhauser’s seems to provide a parallel with gender criticism. Those of the visitors to her installation who were alert to the Blakean connotations of Vala’s veil, will have glimpsed at a critical and revisionist view of the role assigned to Vala in the poem which was named after her, in Jerusalem, and in almost any learned commentary on these works. Immenhauser, it seems, “reads” Blake against the masculine grain, and by doing so she opens up an alternative understanding of Vala and her veil which attempts to visually “explain” some of the fascination which Blake himself apparently felt when creating the mythic character. To take this just one step further, one might classify Plensa’s sculptural montage of the “Proverbs” as an example of a “deconstructive” or a “hypermedia” art, the creation of an unstable artistic reality from seemingly unrelated textual elements, which in a continual flux combine and dissociate to form a variety of meaningful, yet “open” constellations.

Now, does this mean that these contemporary artists work with scholarly methodologies in mind? Or that scholars unconsciously are creating their texts along the same lines that artists create their works? Though Immenhauser and Löchle have indeed written academic theses on Blake, such a conclusion would seem rather ludicrous to me. The construction of abstract analogies between art and scholarship as two “fruits” of the human mind still seems synonymous with comparing apples to peaches. However, to look at contemporary artists’ reactions to Blake’s words and images, and to draw such parallels, may still be a heuristically useful exercise, one that will remind the critic of the plurality of legitimate and potentially meaningful engagements with Blake’s works.

begin page 87 | ↑ back to topThe Artists, Exhibitions, and Catalogues

Verena Immenhauser (b. 1939), Vala: Arbeiten zu Blake, Berner Galerie, Berne, Switz., 1-24 Nov. 1988. On show were the installation “Beneath the Veil of Vala” (as reviewed above), as well as a selection of the artist’s “Vala” photographs and oil paintings (the latter somehow reminiscent of Cy Twombly’s “Wilder Shores of Love”). There was no catalogue, but the exhibition was previously reviewed in Der Bund and by Ester Adeyemi, Berner Zeitung, 12 Nov. 1988.

Dieter Löchle (b. 1952), William Blake—Roof’d in from Eternity, Universitätsbibliothek, Tübingen, Ger., 3 Apr.-25 May 1995. The catalogue, with a note on the artist by Susanne Padberg, translations from Blake’s poetry, and a commentary on Blake’s prophecies by the artist, is being distributed by the Galerie Druck & Buch (Nauklerstrasse 7, D-72074 Tübingen, Ger.). The show was previously reviewed by Kurt Oesterle, Schwäbisches Tagblatt, 6 Apr. 1995: 27. On the occasion of the exhibition, and under the same title, two portfolios with reproductions of Löchle’s designs and his prints in offset lithography were issued in a limited edition of 50 copies each (Tübingen, Ger.: Galerie Druck & Buch, 1995).

Jaume Plensa (b. 1955), “One thought fills immensity,” Städtische Galerie, Göppingen, Ger., 2 July-6 Aug. 1995. The exhibition catalogue contains Blake’s “Proverbs of Hell” and contributions by the artist, Werner Meyer, and Alain Charre (parallel texts in German and English).

Nikolaus Utermöhlen (b. 1958), 1992 Nikolaus Utermöhlen “An Infinite Painting” on A Vision of the Last Judgment by William Blake 1808, Zwinger Galerie, Berlin, Ger., 5 Sept.-10 Oct. 1992. In lieu of a catalogue, the gallery issued an “artist’s book” in an exceedingly small (and expensive) edition. The exhibition has been briefly reviewed in Die Tageszeitung, 15 Sept. 1992.