ARTICLES

William Blake and the Sophocles Manuscript Notebook

In January 1993 the London antiquarian booksellers Bertram Rota Ltd. invited me to inspect a manuscript notebook which contained a number of signatures by a William Blake. Following my inspection I concluded that the manuscript should be considered as once associated with William Blake, the poet, painter and printmaker.

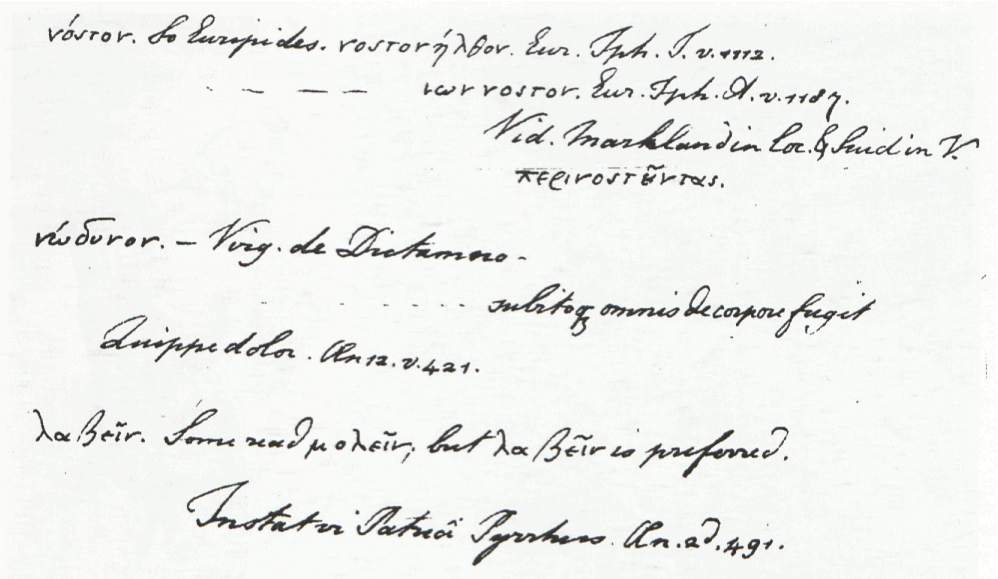

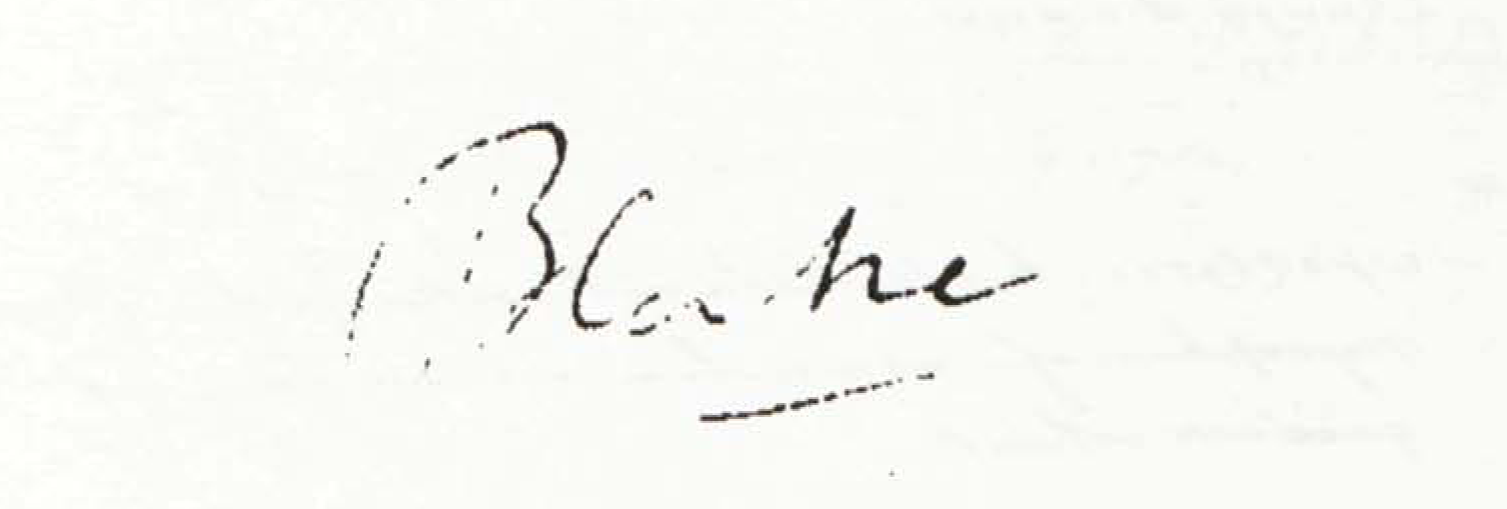

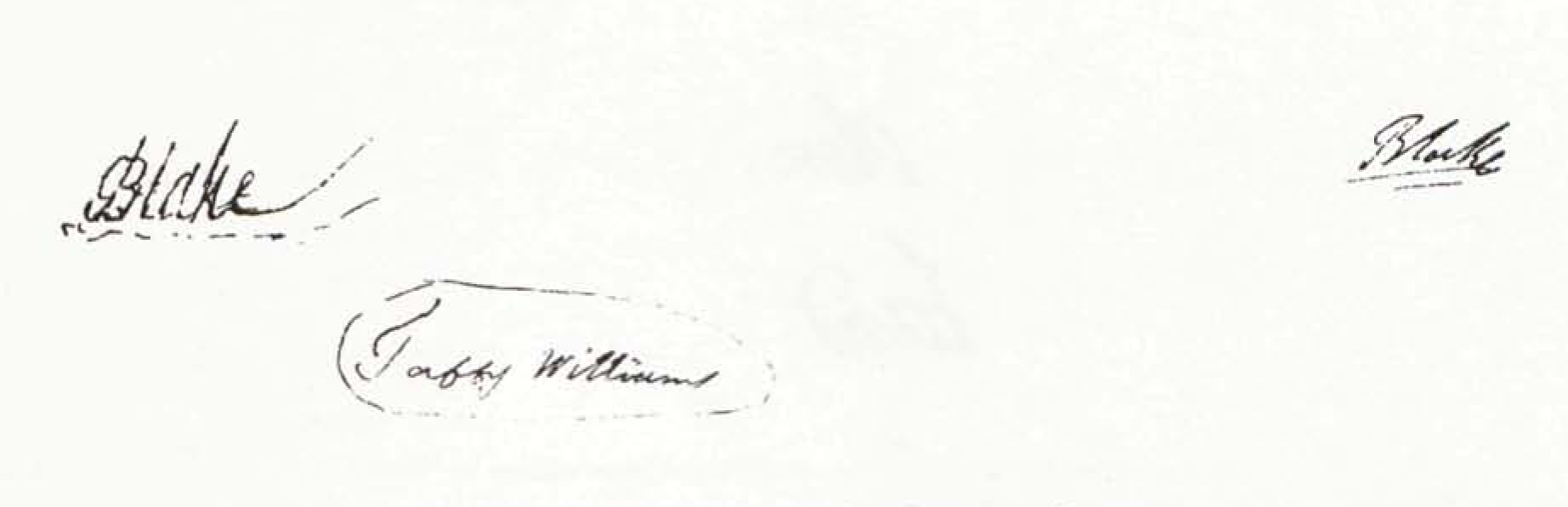

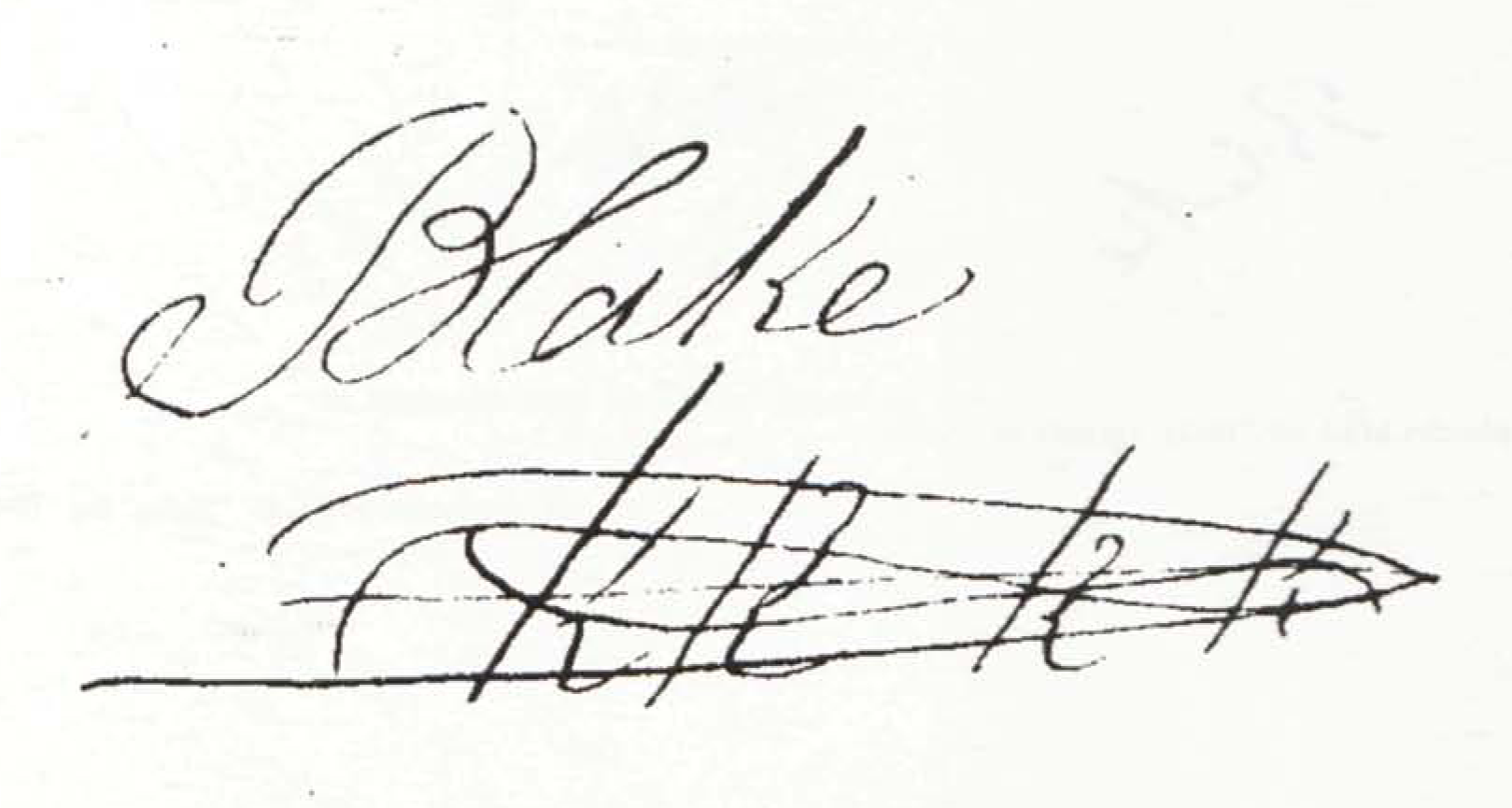

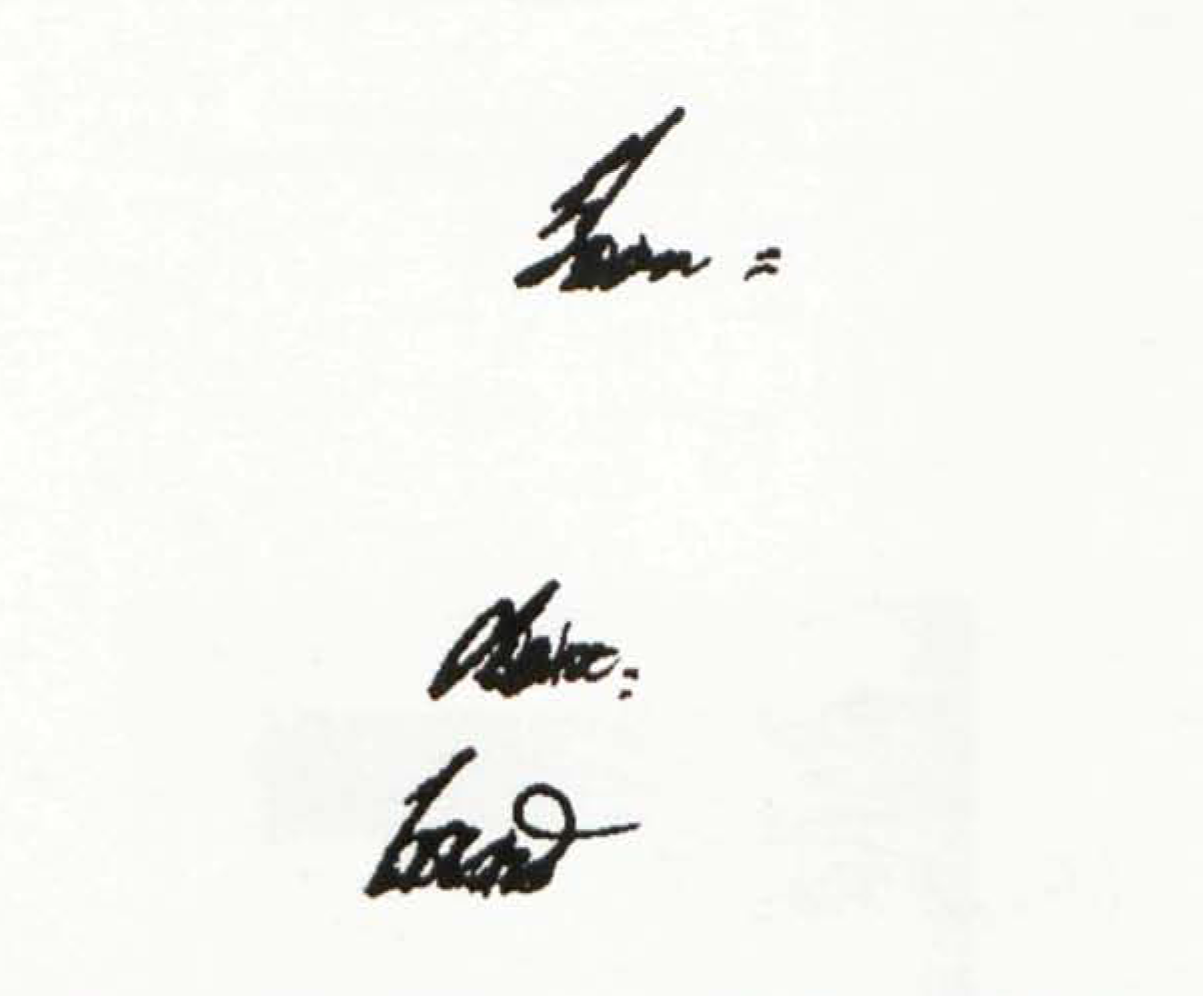

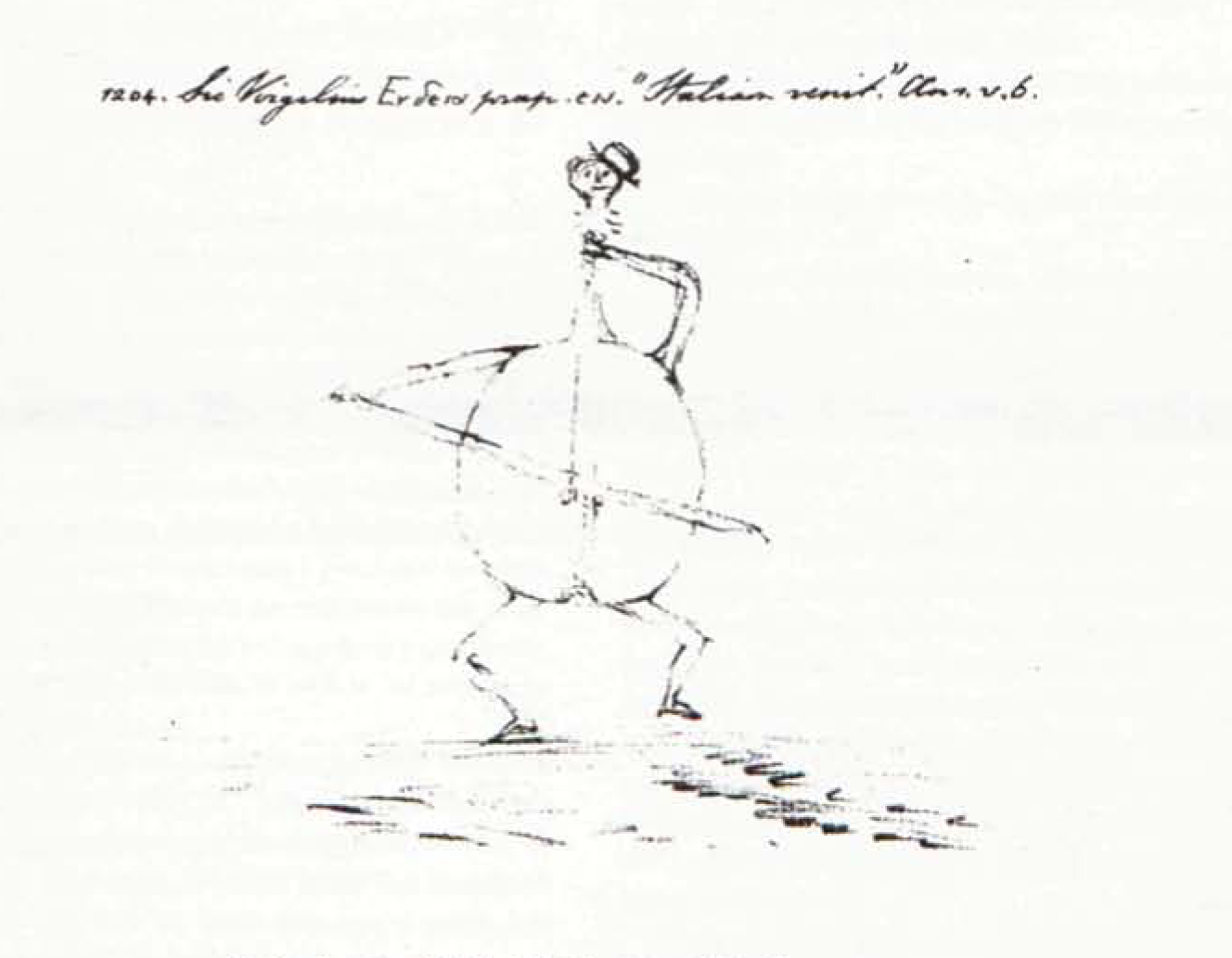

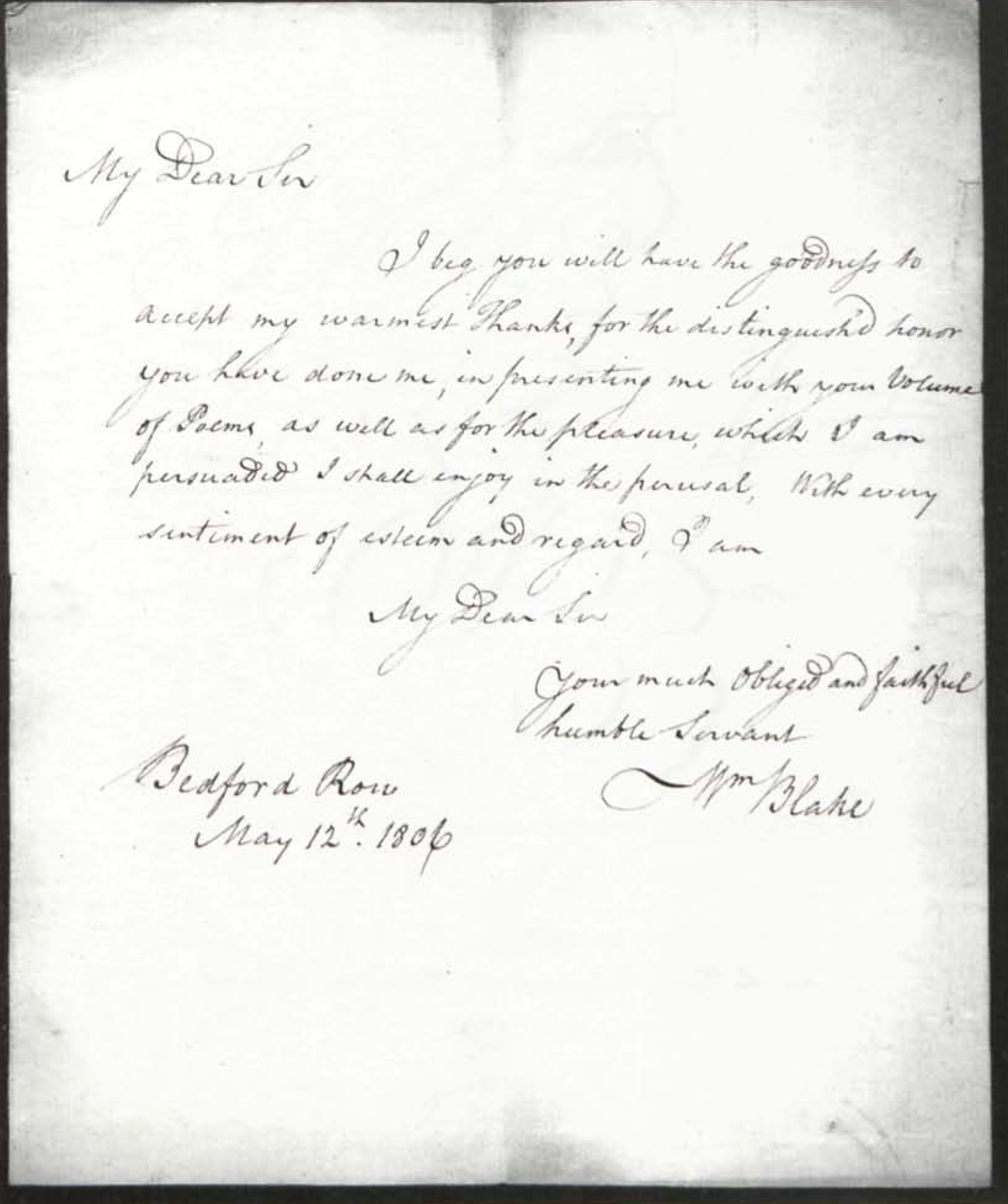

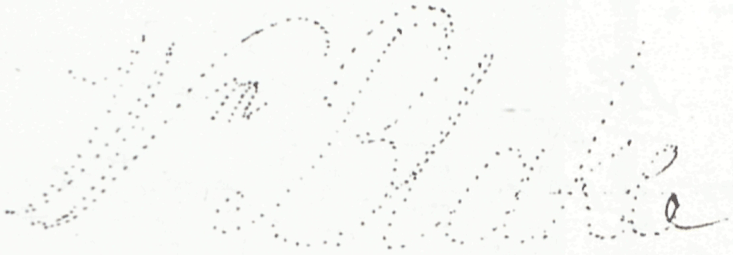

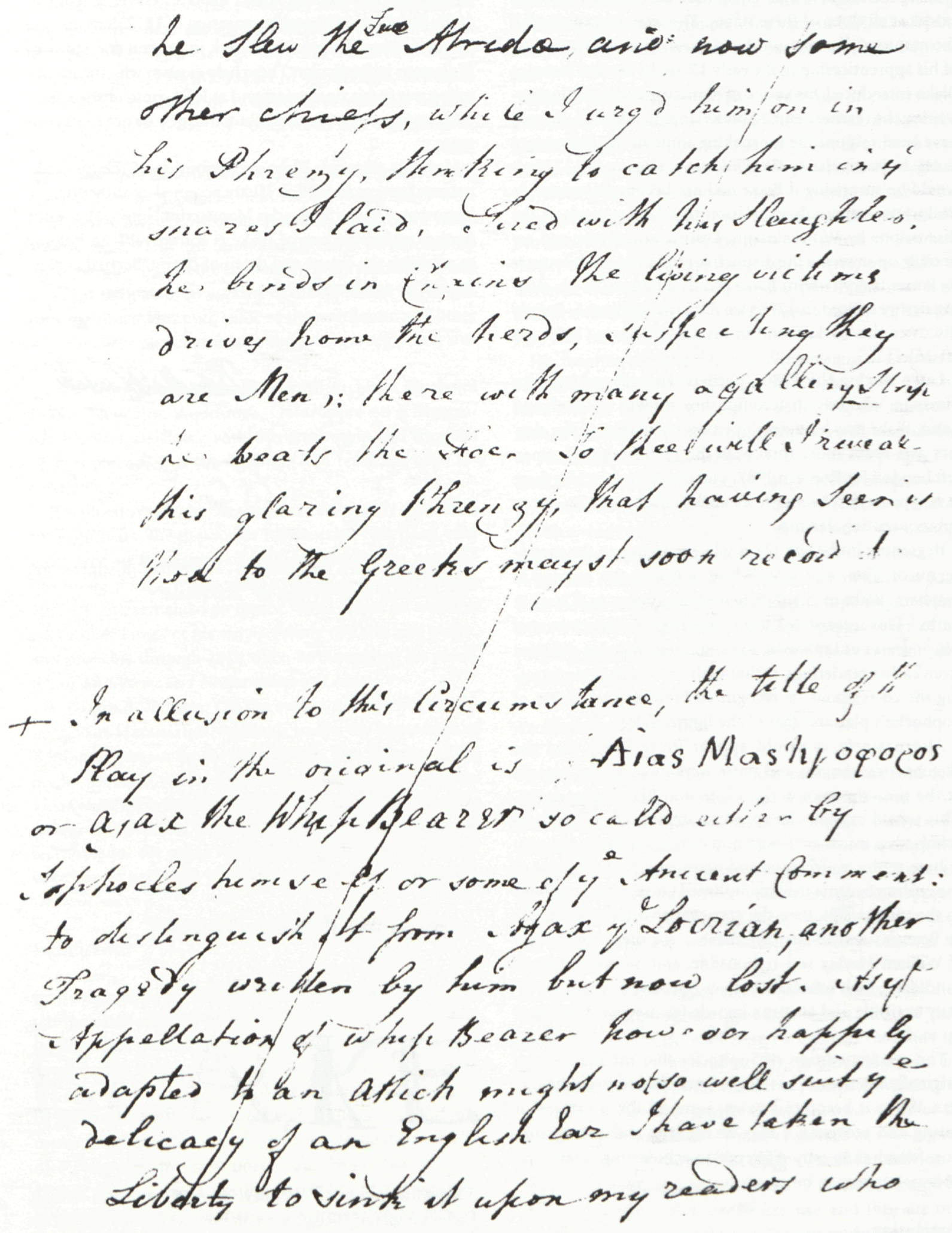

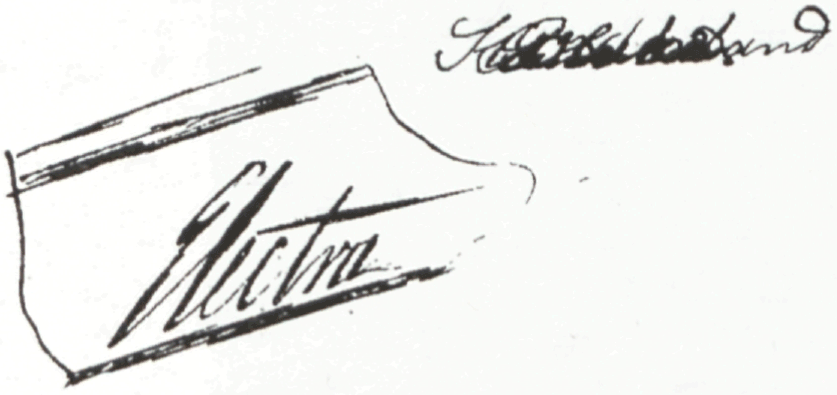

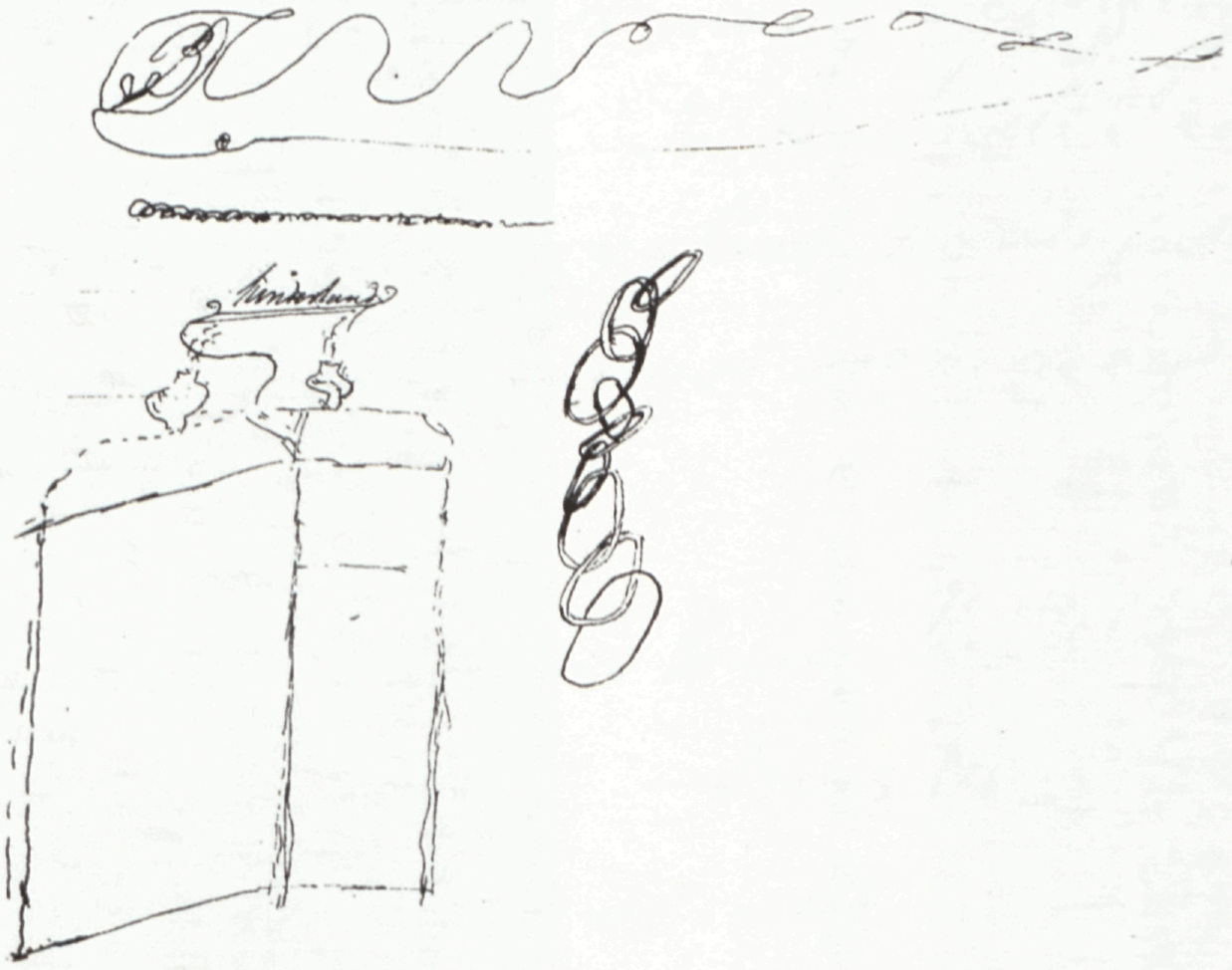

My conviction was based primarily upon the signatures. They were clearly very early and the most convincing examples indicated that they had been made by someone learning basic techniques of printmaking; in particular, those formed of pen and ink dots in the manner of stipple engraving technique (folios 43v and 45v) (illus. 1 and 2) and the experimental example of Blake’s surname printed in reverse or mirror writing (folio 116v) (illus. 3). If they were authentic, these examples suggested that Blake had probably come into possession of the manuscript during the first part of his seven year apprenticeship as an engraver (1772-79).

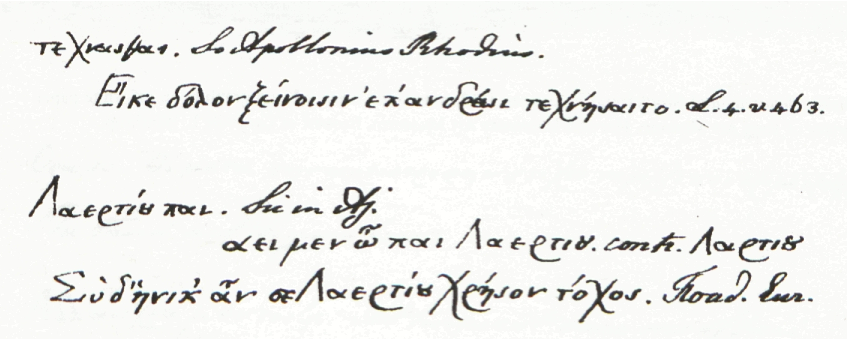

The substance of the manuscript supported an association with Blake. The extant manuscript originally formed the blank leaves used to interleave an octavo letterpress text of four plays by Sophocles. These larger blank leaves had then been used intermittently to write translations of and annotations to the plays in several distinguishable hands, with some examples clearly resembling the hand of William Blake. At a later date, probably in the 1920s, the leaves of printed text had been torn out without breaking the binding. Of particular relevance to Blake was the inclusion of Philoctetes amongst the four plays, the subject of an etching by James Barry first produced in 1777 and of a major painting by Blake of 1812. In a letter to his brother of 1803 Blake had also referred to how accomplished he was becoming in his studies of Greek. Shortly before, William Hayley in correspondence had also made reference to Blake’s study.

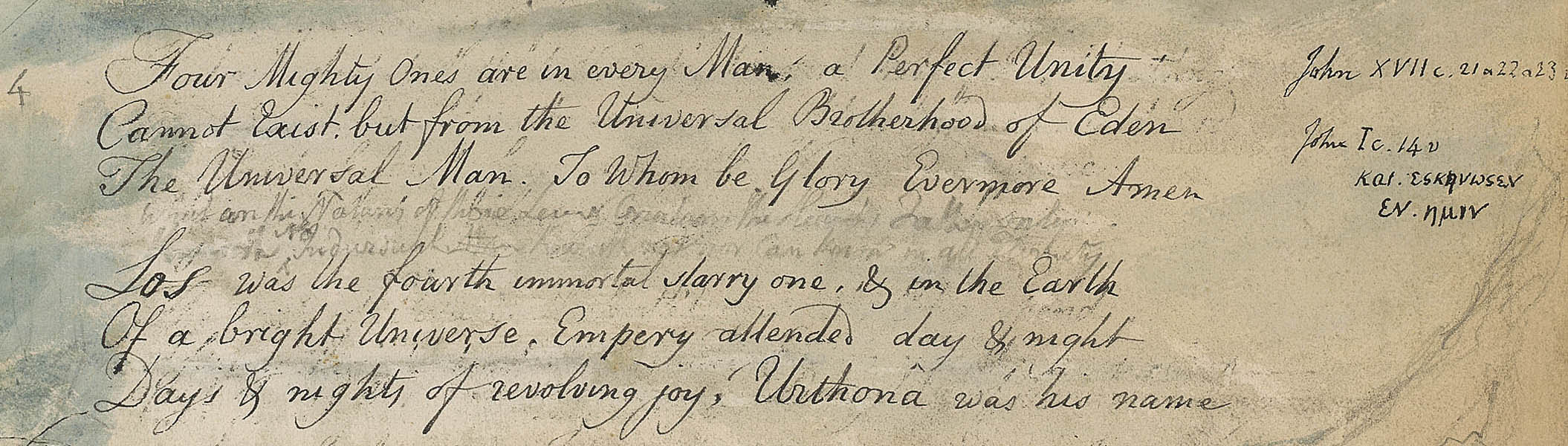

I suggested to John Byrne, then an associate, and to Anthony Rota, head of Bertram Rota Ltd., that the next step should be to take the manuscript to the British Library so that the examples of Greek letter formations in the Sophocles Manuscript Notebook (as it will be referred to) could be compared with the examples in Blake’s holograph present in the manuscript of Vala or The Four Zoas. This would also provide an opportunity to make general comparisons of the holograph with those of Blake written in English in the manuscript of Vala, examples that vary widely in character from copperplate to less formal styles. I later met with John Byrne at the British Library to compare the manuscripts.

The description that follows is the outcome of these inspections and comparisons, together with study and comparisons made on my own with examples of Blake’s holograph from manuscripts as varied as those of “Then She Bore Pale Desire” and “Woe Cried the Muse,” An Island in the Moon, Blake’s letters and receipts to Thomas Butts (Letters from William Blake to Thomas Butts 1800-1803. Printed in Facsimile with an introductory note by Geoffrey Keynes, Oxford, 1926) a range of Blake autograph signatures in particular from books he acquired early in life now in the Cambridge University Library and in my own collection, as well as the manuscript of Vala in the British Library. It is hoped that the illustrations from the Sophocles Manuscript Notebook will be found helpful in providing an opportunity for others to make their own comparisons. They accompany the description through the generosity of the owner, Mrs. Blunden, and Anthony Rota of Bertram Rota Ltd. For just such comparison the description was made available to G. E. Bentley, Jr., in December 1995.

With regard to the translation and annotation of Sophocles plays, the observations and distinctions that are made have been contributed by Alan Griffiths of the Department of Greek and Latin at University College London, without whose expertise the levels of scholarly and linguistic competence present in the manuscript, and the questions of authorship these raise, would not have been made clear. John Byrne, formerly of Bertram Rota Ltd., and Scot McKindrick, of the Department of Manuscripts at the British Library, have also contributed, especially in identifying similar idiosyncratic Greek letter forms present in the manuscripts of Vala and the Sophocles Notebook.

Included in the description are also my own speculations regarding similarities of handwriting which deserve to be assessed allowing for the wide variation of Blake’s holograph over the course of his lifetime, as well as an indication of the circumstantial evidence that needs to be taken into account. It is the early signatures combined with the circumstantial evidence that persuade me that the manuscript deserves to be taken seriously. If an association is accepted, its significance for our further understanding only begins with the few suggestions that have been made here.

Description

The Sophocles Manuscript Notebook is made up of 189 leaves, approximately 20.5 × 16.5 cm. The binding is unsophisticated, of eighteenth century marble paper covered boards and vellum spine, the latter partially defective and begin page 45 | ↑ back to top in a fragile state, and lettered in pen and ink “BLUNDEN” directly onto the spine.

The paper bears an undated watermark of Britannia within an oval frame surmounted with a crown and with the initials “G R” below. An example is found on folio 12 recto. It can be dated confidently before 1794, when this design went out of use. The earliest examples are from the mid to late 1760s. The present example is extremely simple: there is no writing around the outside of the oval and the drapery is plain. According to Edward Heawood, Watermarks Mainly of the 17th and 18th Centuries (1950), the simplest forms are the earliest, indicating that the paper used in the Sophocles Manuscript Notebook was produced near the beginning of this period.

It is apparent from offsetting of varying strength throughout the Sophocles Manuscript Notebook that it was originally interleaved with a printed text of four plays by Sophocles: Ajax, Electra, Trachiniai and Philoctetes. At a later date the leaves of printed text were pulled free or torn away from the binding leaving some stubble still stitched in place. The text of Sophocles used for interleaving has not yet been determined, but the offset is clear and special photography and comparison will eventually make it possible to establish the edition used. Traces of pen marks or ticks against line endings and other forms of marginalia may be seen on some folios where these marks have continued beyond the edges of former interleaved text pages, as on folio 96 recto.

The handwriting is in various shades of sepia ink. Some sketches have been made using pencil.

The Sophocles Manuscript Notebook may be divided into four sections:

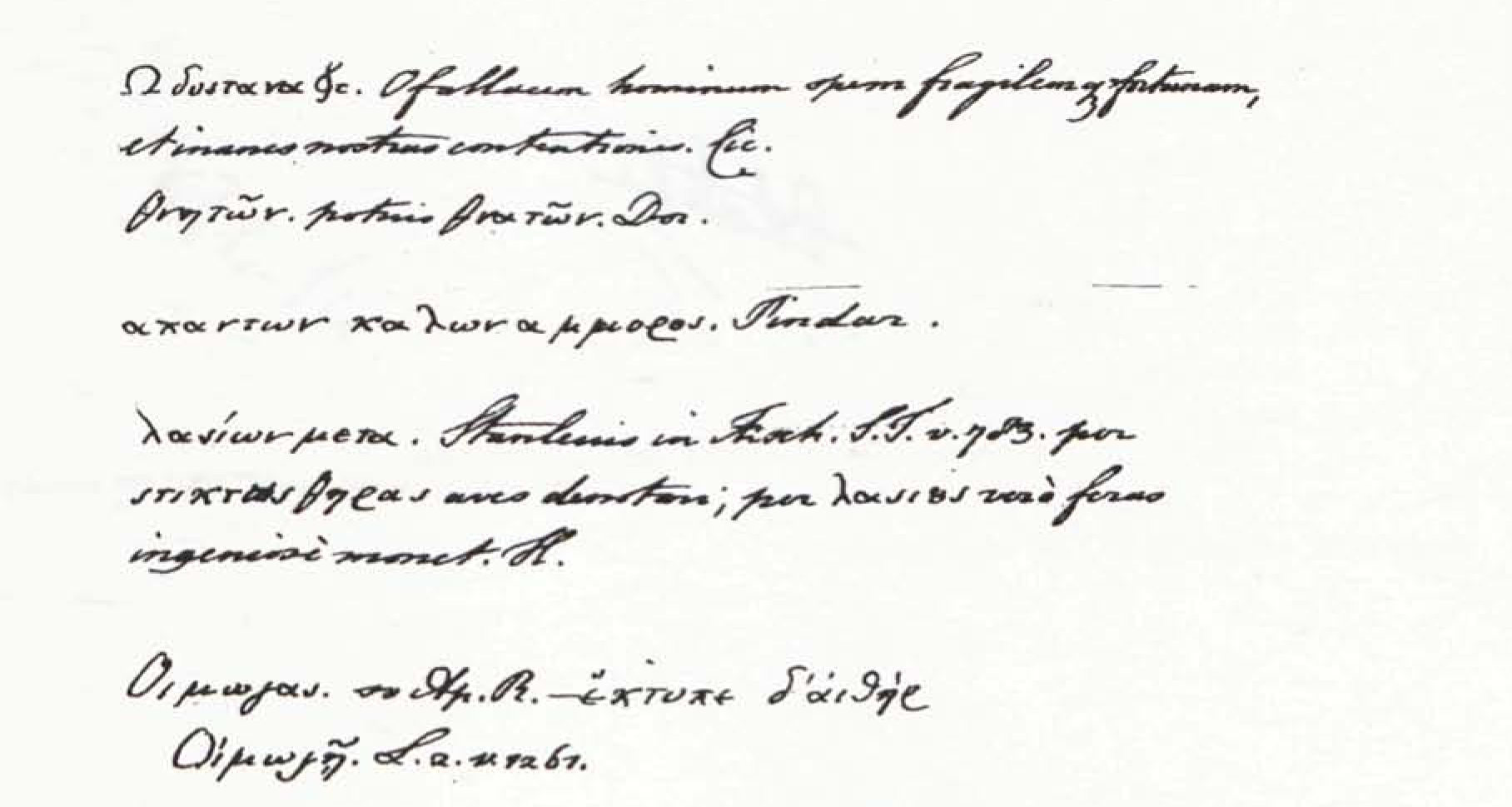

1. Verso front free end-paper to folio 22 recto. These folios contain an incomplete translation into English of Ajax, with some comparative notes found on folios 5 verso and 7 verso (illus. 4). The handwriting in this section of the Sophocles Manuscript Notebook is mature and often fine (apart from the unsophisticated Greek on the front free end-paper and folios 4 recto and 7 verso). If the handwriting in English in this section is that of William Blake, a date later in Blake’s life for this translation is likely. Examples of the handwriting in this part of the Sophocles Manuscript Notebook may be compared with that in the manuscript of VALA Night the First, especially folios 4 through 9 verso (paginated in the Vala manuscript 7-18).

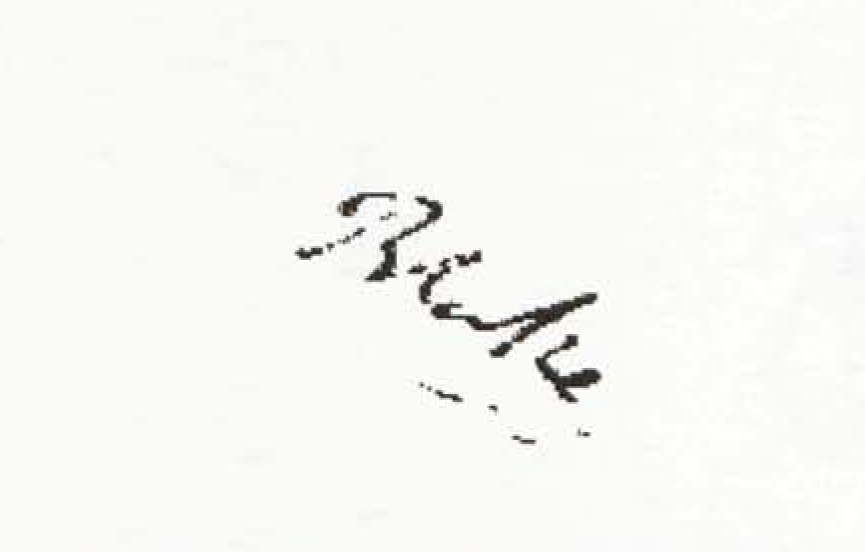

The Greek letter formations present in the Sophocles Manuscript Notebook on folio 7 verso (see illus. 4) are immature and indicate a beginning student. They are compared with those present in the manuscript of VALA Night the First, folio 2 recto (page 3) (illus. 5, detail; illus. 6, another detail). There are no examples of William Blake’s signature or other signs that would have drawn attention to the significance of the volume in this section.

2. Folios 23 recto to 37 recto. These folios contain Edmund Blunden’s autograph manuscript reminiscences entitled Some Notes on Friends & Acquaintances, describing a meeting with Siegfried Sassoon and others in 1921, and his first visit to Thomas Hardy at Max Gate in 1923. From Blunden’s hand it is believed that this was written within a few years of the events which it describes. This also indicates the period by which the Sophocles Manuscript Notebook had come into Blunden’s possession, possibly together with two other volumes. A bookseller’s note on the front paste-down reads “3 Vol £1-0-0.” A search of the remains of Blunden’s library in February 1993 did not discover the other two volumes, if they had been purchased as a lot by him. Blunden habitually bought fine blank paper cheaply whenever he could and he may well have acquired the present volume (alone) for this purpose.

Although Blunden considered himself “an old reader of Blake,” as he remarked in the brief foreword to Bunsho Jugaku’s Bibliographical Study of William Blake’s Note-Book (Tokyo, 1953), he appears to have paid little regard to the possible significance of the Sophocles Manuscript Notebook. During the course of writing his description of his visit to Hardy on folio 35 recto he deleted an early Blake signature isolated among the sequence of blank leaves he was using. There is also no record of his having shown the Sophocles Manuscript Notebook to his friend Geoffrey Keynes, although on at least one occasion he had invited Keynes’s opinion on what he hoped to be a Blake discovery. This was a watercolor wash drawing contained in a manila envelope upon which Blunden recorded Keynes’s response: “Not remotely possible.” Blunden may also have been responsible for removing the printed text of Sophocles, of which only offset and occasional stubble remain.

3. Folios 37 verso to 140 recto. These folios contain a number of blank leaves but they also form a distinct section as they contain a series of what appear to be William Blake’s early autograph signatures: on folios 43 verso, 45 verso, 48 recto, 60 recto, 71 recto, 79 recto, 81 recto, 83 recto, 91 recto, 103 recto, 113 recto, 114 recto and 116 verso; in addition to the signature on folio 35 recto deleted by Blunden. Two examples, on folios 43 verso and 45 verso, are formed of pin prick dots in the manner of stipple engraving (see illus. 1 and 2). Another example, on folio 116 verso, in roman capitals may be an early if not first attempt at reverse writing (see illus. 3). The only other example of Blake practicing reverse writing is later, where he has written the first three letters of his surname on the verso of the last leaf of the manuscript of An Island in the Moon. These examples on folios 43, 45 and 113 verso are indicative of an apprentice engraver learning his craft.

The early signatures present in the Sophocles Manuscript Notebook may be most usefully compared with those found begin page 46 | ↑ back to top in the earliest examples present in Blake’s manuscript of An Island in the Moon (folio 16 verso) and in the books he owned and signed in his youth.

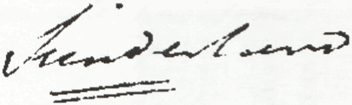

The name “Sunderland” appears frequently throughout these leaves. In almost every instance it has been overwritten with the signature “Blake”; for example, on folios 43 verso, 50 recto, 71 recto, 79 recto, 91 recto (illus. 7) and 114 recto, in addition to the example on folio 24 recto (illus. 8). This sign of previous ownership and of the effort to obscure it may explain why these pages were otherwise largely left blank, though blank leaves are also found in the manuscript of An Island in the Moon. There is no known association between a “Sunderland” and Blake nor between Blake and a “Taffy Williams” whose name is found on folio 103 recto. There is also one example of doggerel verse on folio 48 verso (cf. Macbeth, IV.i.10f):

In trouble to be troubled,

Is to have your trouble doubled

The handwriting in this section of the Sophocles Manuscript Notebook appears to be of the early 1770s (with the exception of the doggerel verse), the beginning of Blake’s seven year apprenticeship to the engraver James Basire (1772-79). This is suggested by the graphic experiments that have been noted as characteristic of a beginning apprentice engraver and the obvious immaturity and variation of the signatures.

There are also several casual sketches in this section. They show little promise of the William Blake, but the interlinking circles on folio 71 recto (illus. 9) could anticipate the links of chain decorating the inside margin of plate 65 of Jerusalem and the sketch on folio 79 recto (illus. 10), of a moth emerging from a chrysalis, could possibly anticipate similar devices used on the frontispiece to The Gates of Paradise (1793) and the separate plate known as Albion Rose.

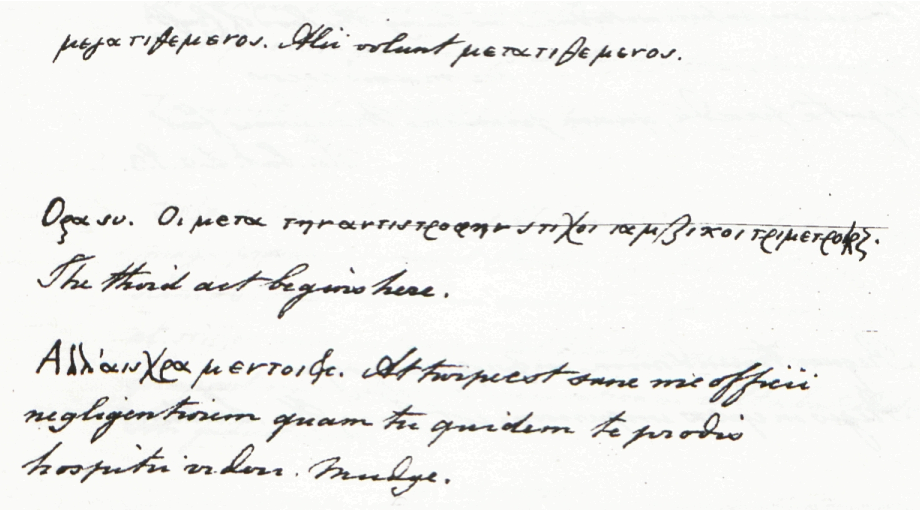

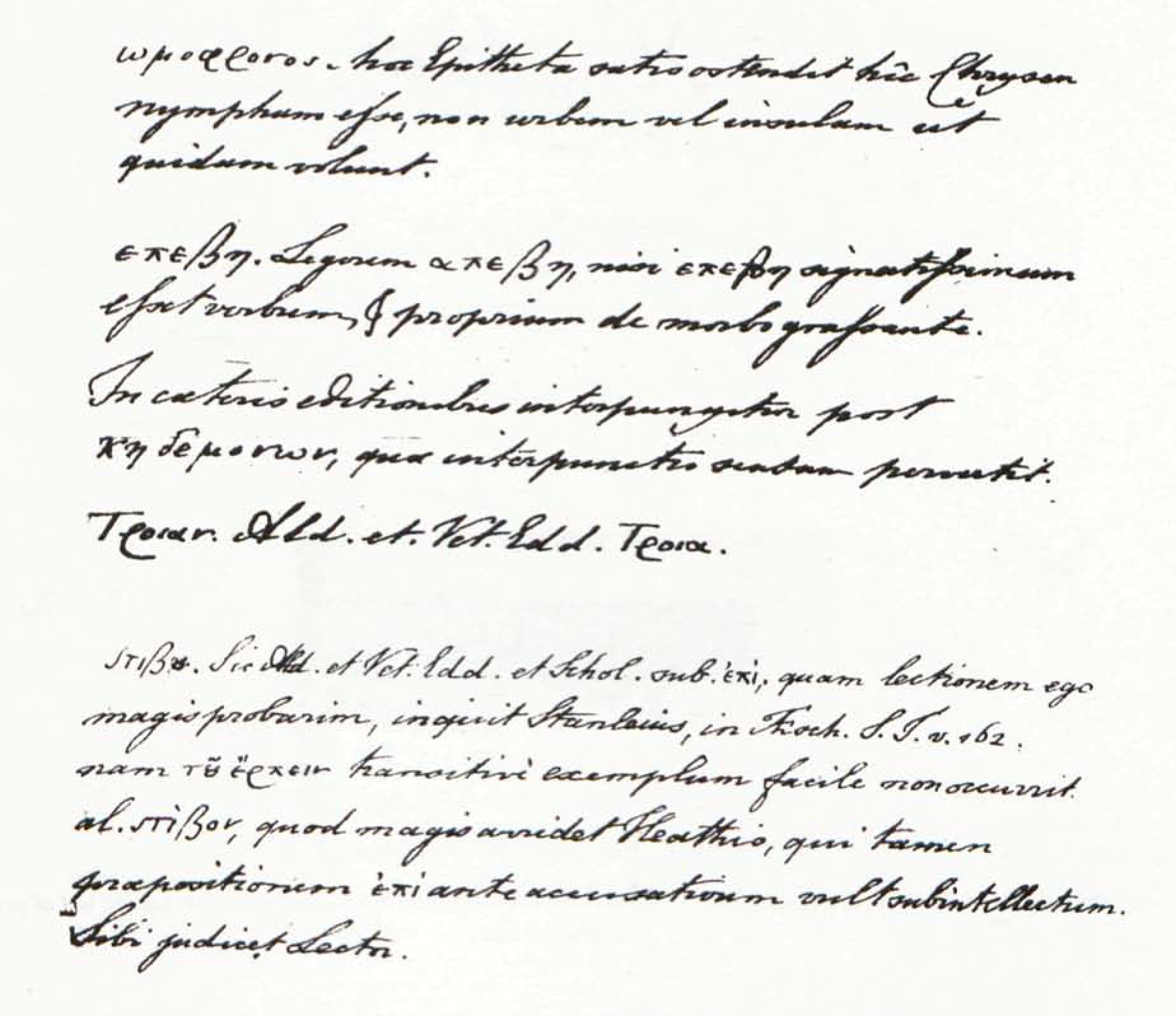

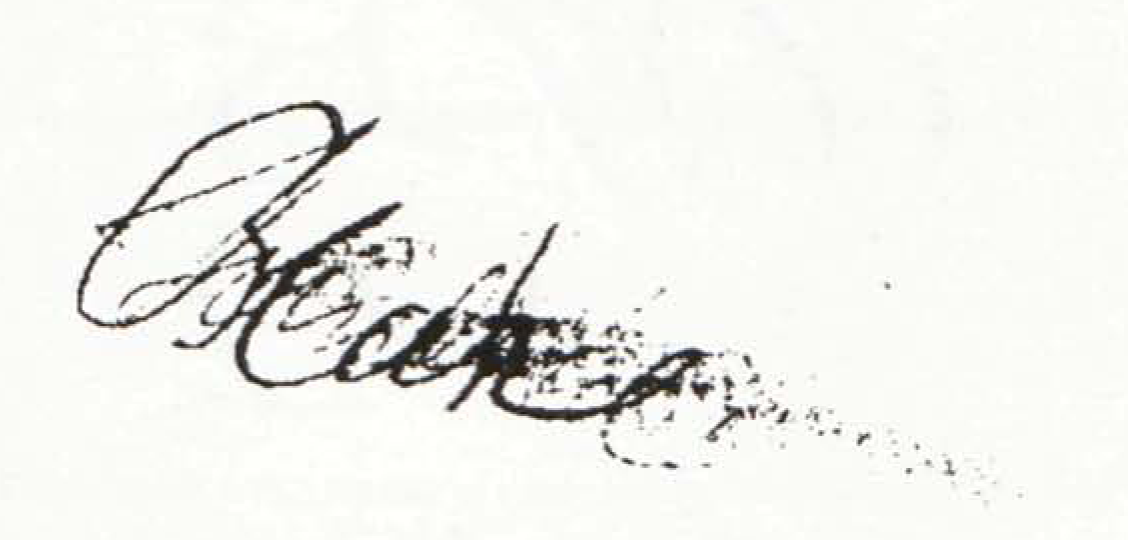

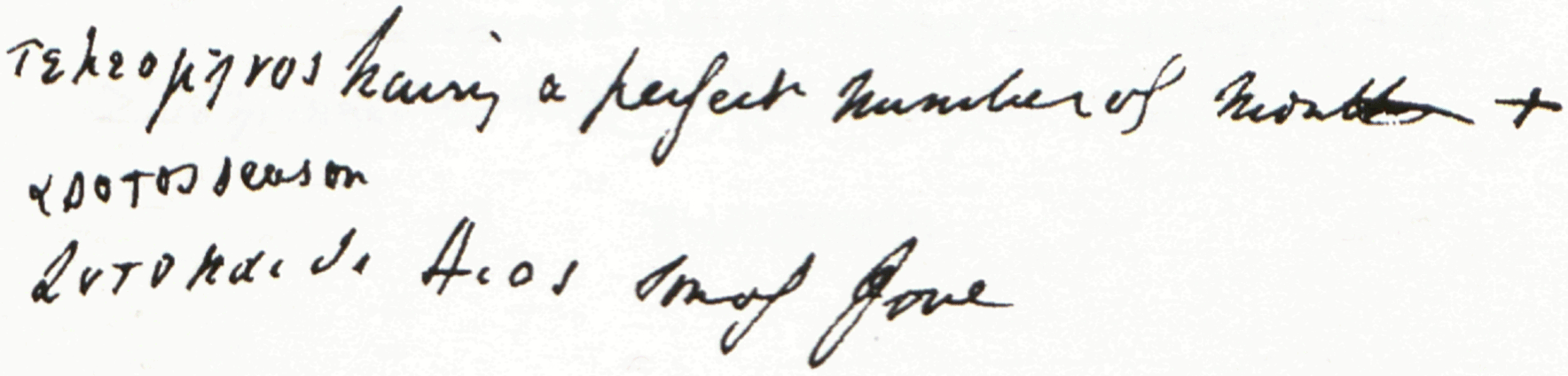

4. Folios 140 recto to 189 verso. These folios contain detailed notes made in the course of studying Philoctetes. These include remarks on the Sophoclean tragic form, numerous citations of other classical writers both Greek and Roman, reference to Milton’s Paradise Lost on folio 172 verso, and comparative notes on linguistics and related themes. All authors and editions cited are earlier than c. 1785.

If the notes in this section of the Sophocles Manuscript Notebook are to be attributed to William Blake they probably belong to the period c. 1800-12. These dates are suggested by comparisons with Blake’s holograph in contemporary letters and receipts to Thomas Butts and in the manuscript of Vala. Specifically, examples in the Sophocles Manuscript Notebook on folios 159 verso, 169 recto, 171 recto and 172 recto and verso may be compared with the copperplate capital letters in VALA Night the First, folios 7 and 9 recto.

Attributing this section of the Sophocles Manuscript Notebook to the period c. 1800-12 may also be predicated on the assumption that Blake’s detailed scholarly interest in Philoctetes was prior to production of his pen and watercolor painting Philoctetes and Neoptolemus at Lemnos, now in the Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University. The painting is signed “W Blake. 1812.” A description of the painting is given in Martin Butlin’s catalogue, The Paintings and Drawings of William Blake (1981), No. 676 (see illus. 17).

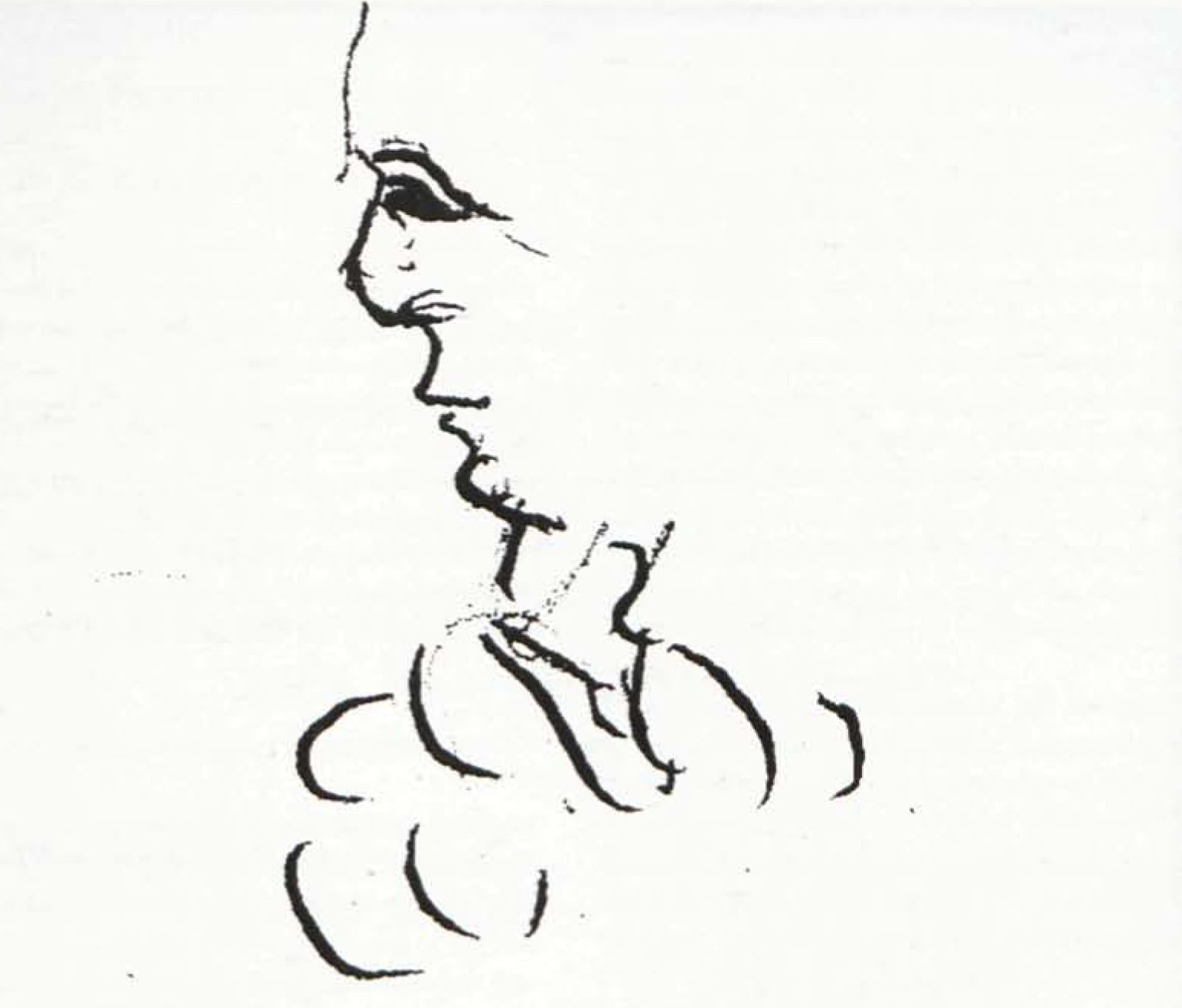

This section of the Sophocles Manuscript Notebook also contains several sketches in pen and ink or pencil on folios 116 recto, 147 recto and verso, 149 verso, 150 recto, 181 recto, 182 verso, 183 recto, 186 recto, and rear paste-down. They were probably made by some one other than Blake, perhaps by “Blandford” whose ownership signature is found at the beginning of the manuscript (see below under Provenance).

This period is also suggested by Blake’s study of Greek and Latin referred to in a letter to his brother James written from Felpham on 30 January 1803, as follows:

I go on Merrily with my Greek & Latin; am very sorry that I did not begin to learn languages early in life as I find it very Easy; am now learning my Hebrew [Hebrew letters for ABC]. I read Greek as fluently as an Oxford scholar & the Testament is my chief master: astonishing indeed is the English Translation, it is Almost word for word, & if the Hebrew Bible is as well translated, which I do not doubt it is, we need not doubt of its having been translated as well as written by the Holy Ghost.

Blake’s remark that “the Testament is my chief master: astonishing indeed is the English Translation, it is Almost word for word” suggests that he is still at an early stage, New Testament Greek being far less demanding than classical Greek. He is also relying upon an English translation that he probably knows by heart.

During his stay at Felpham Blake’s study of Greek and Latin was undertaken with the help of William Hayley. Writing in February 1802 to the Rev. John Johnson, Hayley enclosed a titlepage for his new edition of William Cowper’s translation of Homer together with a motto, commenting: “which I and Blake, who is just become a Grecian, and literally learning the language, consider a happy hit!” Referring to Blake, Hayley concludes the letter: “The new Grecian greets you affectionately.” This assessment of Blake’s proficiency as a beginning student of Greek in February 1802 set alongside Blake’s own remarks of January 1803 further suggests that great progress in the writing of Greek was not made at this time, in spite of both Hayley’s and Blake’s enthusiasm.

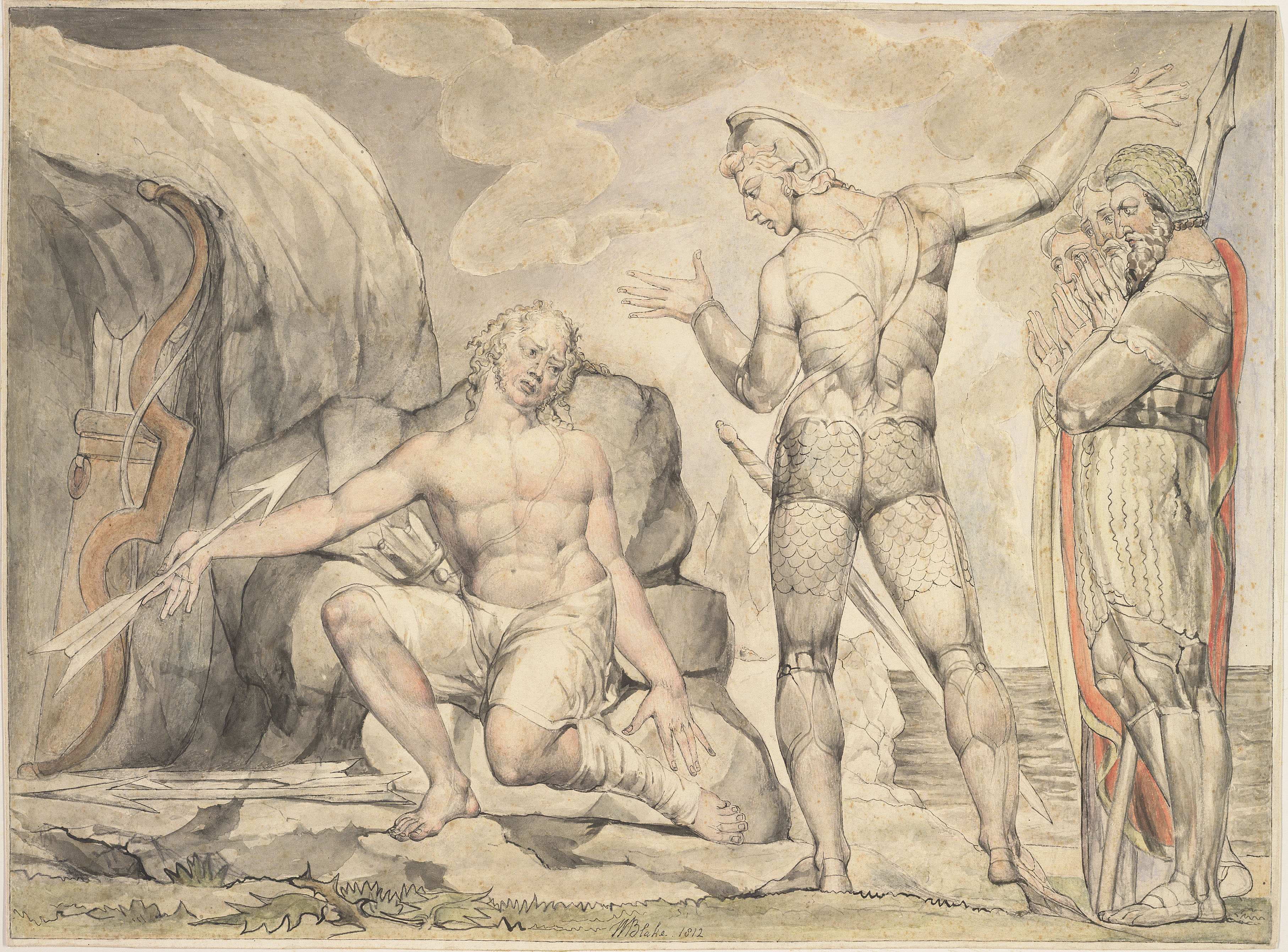

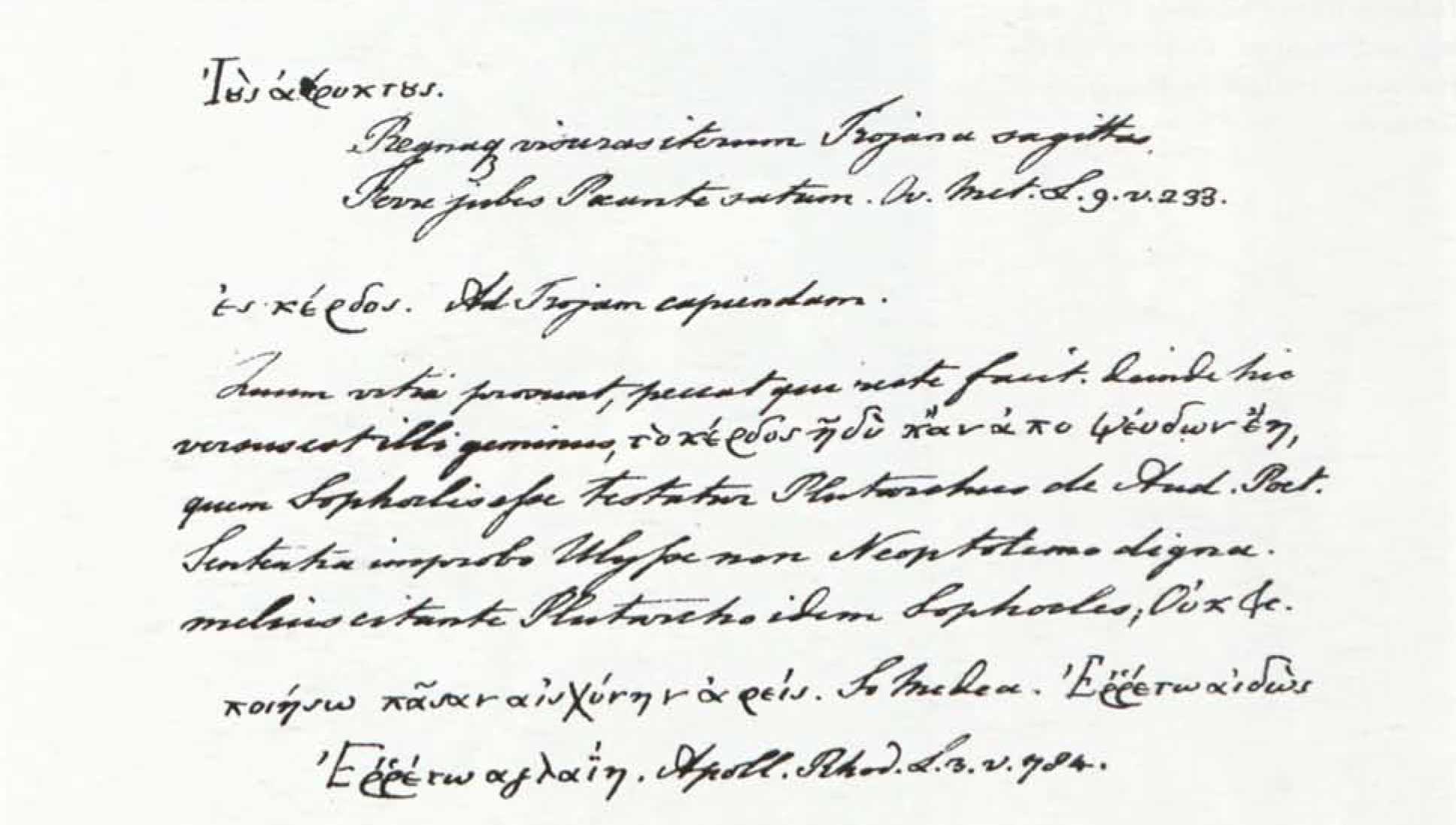

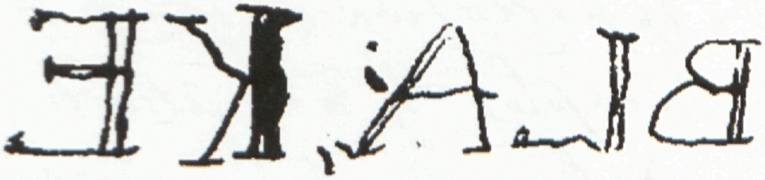

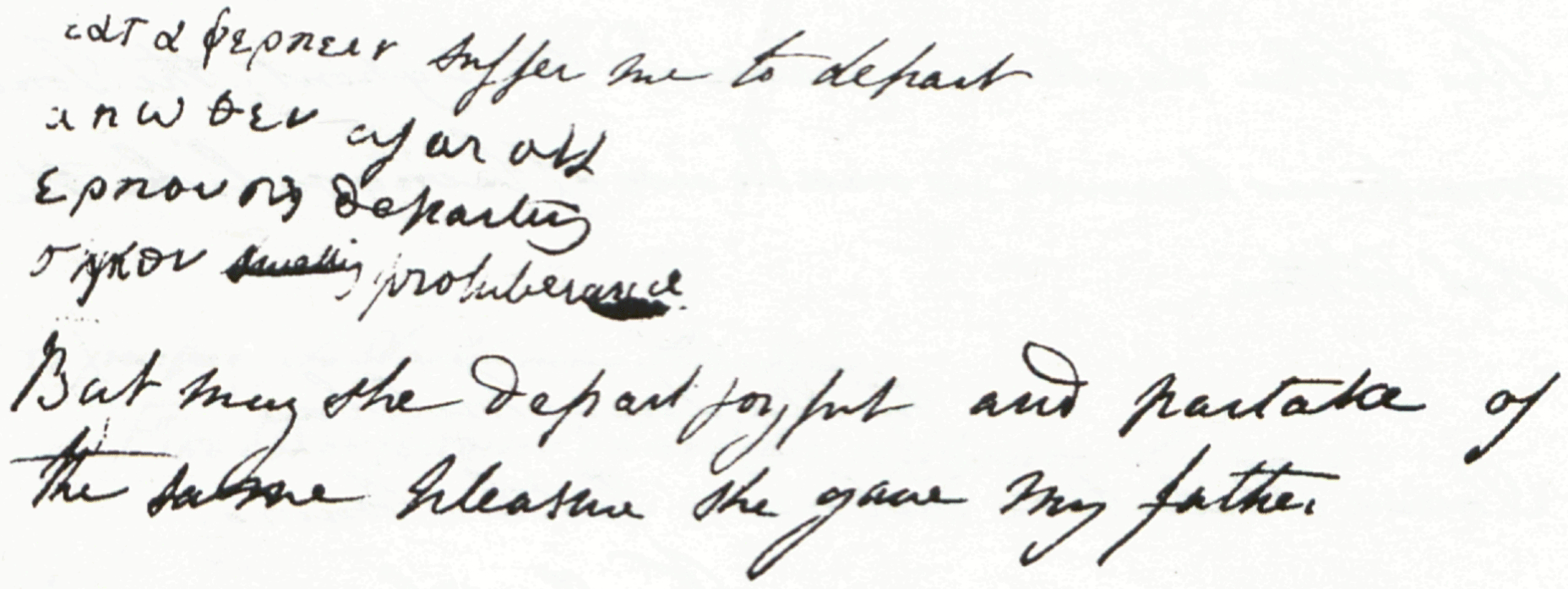

begin page 47 | ↑ back to topThe immaturity of some of the examples of Greek in the Sophocles Manuscript Notebook, especially idiosyncrasies of letter formation, can be compared with an epigraph from Ephesians vi 12 written at the top of folio 2 recto of the manuscript of VALA Night the First (see illus. 5). John Byrne made the following comparisons. Following John Byrne’s examples of erroneous letter-forms found in the Sophocles manuscript I have inserted in brackets similar examples of the erroneous letter-forms as written by Blake in the quotation from Ephesians taken from the VALA manuscript:

While the quotation from Ephesians used as the epigraph to Vala is brief, a few observations may be made. It is carefully, even stiltedly, written (and without accents). Certain quite distinctive letter-forms appear nonetheless, all of which may be found in the Sophocles Manuscript Notebook:

The epsilon(one stroke) rather than ϵ (two strokes): see Sophocles Notebook f.4 recto and f.140 recto and verso (illus. 11 and 12-13) [VALA

]

The sigmaused at the beginnings of, and within, words rather than σ: see f.7 verso (see illus. 4); f.153 verso, line 18 (illus. 14); f.154 verso, line 1 (illus. 15) [VALA

].

The omicron/upsilon diphthong written with the second letter on top of the firstrather than beside it ου: see f.155 verso, line 4 (illus. 16). [VALA

]

The phi written in a single strokerather than the more conventional two strokes ϕ: see f.7 verso (illus. 4). [VALA

]

General observations on the Greek in the Sophocles Manuscript Notebook:

Verso of front free end-paper: the word is incomplete and ineptly written.

f.4 recto: not confidently written; still employing the single-stroke epsilon

f.7 verso: almost certainly written later: more fluent and with more character.

f.84 recto: these capitals are very poor, being of different heights and badly slanted.

ff.140 recto and 144 recto: again not very confident; employing the single-stroke epsilon and, unusually, the sigma. Perhaps predating Vala.

f.151 verso: hazarded as later than Vala; one ς is employed, but the two-stroke epsilon appears, also accents.

f.153 et seq.: the Greek is now written with skill, individual character (and beauty), demonstrating considerable mastery. This must surely be later than Vala.

Scot McKindrick, Greek handwriting expert in the Department of Manuscripts of the British Library, also compared the epigraph from Ephesians on the titlepage of Vala, Night the First (see illus. 5) and the passage on folio 4 recto of the Sophocles Manuscript Notebook (see illus. 11):

The character of the writing style of each passage as a whole, its accent, is different, indicating that they are not by the same hand. However, both share the characteristics of being untutored and demonstrate the same mistakes in letter formation. Also, the respective context of writing is entirely different. In the Vala manuscript Blake is copying onto his titlepage the passage from Ephesians from a text of the New Testament and writing it like one would write a passage in English. The passage on folio 4 recto in the Sophocles manuscript is written as part of a learning exercise in classical Greek, which comparatively is very difficult.

Apart from the few letters of Greek engraved on the separate plate of Blake’s Laocoön (c. 1820), which show an improvement in letter formation, the only other example that may indicate how much he improved after writing in the manuscript of Vala is present in his annotations in a copy of Robert John Thornton, The Lord’s Prayer, Newly Translated from the Original Greek (1827, p. 2) in the Huntington Library, which I have not been able to compare.

If Blake is responsible for these two sections or parts of them, Section I of the Sophocles Manuscript Notebook (the translation of Ajax) should probably be thought of as belonging to the period of nearly a year indicated by Hayley’s letter of February 1802 and Blake’s letter to his brother of January 1803. The study of Philoctetes presumably came later and nearer the time of his painting of 1812. A comparison of Blake’s painting (illus. 17) and Barry’s engraving (1777 reworked in 1790) (illus. 18) makes clear that Blake made a thorough study of the play that led to his own distinctive interpretation.

Provenance

1. Blandford. On the front paste-down is the signature “Blandford,” apparently a signature of ownership but with no date associated with it. It seems likely that Blandford was the original owner, but none of the handwriting in the volume compares with that of the signature. There is no known association between a “Blandford” and Blake.

The name “Blandford” is written in the style of a nobleman, and on a number of occasions elsewhere in the manuscript, but in a quite different hand, is written the name “Sunderland.” As Alan Griffiths first pointed out to me, the combination of the two names “Blandford” and begin page 48 | ↑ back to top “Sunderland” suggests the possibility that the manuscript may have once been associated with the Spencer family; in particular, perhaps, George (Spencer), fourth Duke of Marlborough (1739-1817), Earl of Sunderland, and until 1758 styled Marquess of Blandford, or possibly his son George (b. 1766), Earl of Sunderland and Marquess of Blandford.

The manuscript originally interleaved the printed texts of four plays by Sophocles, and the surviving leaves were then used to make translations and notes. Some of the notes are impressive and call upon a wide range of scholarship up to the latter part of the eighteenth century, possibly those of a professional tutor working in the middle or later eighteenth century. However, some of the translation and other notes are also very elementary, suggesting a beginning student.

I also wrote the Secretary, Historical Archives, Blenheim Palace, Blenheim, Woodstock, Oxfordshire on 6 September 1993 for assistance with this attribution and supplied with photocopies of the signature. No reply has been received.

2. William Blake. On the evidence of the early signatures in Section III, the Sophocles Manuscript Notebook may have been in possession of William Blake from near the beginning of his apprenticeship to the engraver James Basire 1772-79 and remained so until c. 1803, when he wrote to his brother James of his current study of Latin and Greek, and probably through 1812 when he completed his painting of Philoctetes and Neoptolemus at Lemnos.

3. Edmund Blunden. On the evidence of Section II, the Sophocles Manuscript Notebook was in the possession of Edmund Blunden by the early 1920s. The identity of the bookseller from whom Blunden purchased it, and its previous ownership apart from Blandford and Blake, remains unknown. As noted, in early 1993 Mrs. Blunden helped in searching for the other two volumes of the “3 vol. £1.0.0” noted by an unknown bookseller on the front paste-down, without success.

Significance

If the signatures of William Blake are accepted as authentic, the early sections of the Sophocles Manuscript Notebook present new insight into the beginnings of Blake’s apprenticeship, not least in providing evidence of his attempting reverse writing, a point of contention for many years by those attempting to understand his invention and processes of Illuminated Printing with which he produced his own composite works of poetry and design. For the biographer, there is the intriguing possibility of a connection between the name “Sunderland,” compulsively overwritten with Blake’s own surname, and also the name “Taffy Williams.”

The Sophocles Manuscript Notebook reveals a background of interest and scholarship hitherto unsuspected, especially for the period during which Blake was writing Milton and Jerusalem and painting various biblical subjects including the great series of interpretations of the Book of Job.

Blake’s knowledge of native traditions of poetry and painting as well as those of other cultures has always been acknowledged. We know he studied Italian in order to read Dante in the original. From the letter written by William Hayley and Blake’s own to his brother James, we know that he also studied Latin and Greek as well as ancient Hebrew. But until the discovery of the present manuscript just how deeply and wide-ranging these studies were, especially in terms of the secondary scholarship that Blake may have sought and mastered, has largely been a matter of conjecture and internal reference.

His painting of Philoctetes and Neoptolemus at Lemnos at Harvard can be understood in a new light. Until now we have known little of the period following the failure of Blake’s Exhibition of 1809 and completion of his painting in 1812: the period Gilchrist calls “Years of Deepening Neglect,” Life, ch. 27. Apart from its biographical implications, and importance in relation to Milton and Jerusalem, Blake’s detailed study of Sophocles’s play should now be set alongside the revival of his interest in the Book of Job, also at this time, and recognized as the classical counterpart to Job’s trial, isolation and redemption through suffering. In short, Blake’s study of Philoctetes forms an integral part of his preparations for his greatest work of interpretation as a graphic artist.

Problems of Attribution

As indicated, there is intermittent evidence in the Sophocles Manuscript Notebook of a favorable comparison of the handwriting with examples from Blake’s manuscripts. But the extent of the handwriting that can be attributed to William Blake can only be properly assessed when the levels of sophistication of translation and scholarship are appreciated. In this regard, Alan Griffiths pointed out that there are three distinctive personalities who are present in the manuscript.

There is a beginning student, as on folio 4 recto (see illus. 11). There is a competent translator, as on folio 167 recto (illus. 19). And there is an expert scholar, as on folios 156 and 157 (illus. 20-21 and 22-23), in particular who has added comments opposite the text of Philoctetes which demonstrate an extensive and at times impressive use of the scholarship available up to mid-century, but who significantly does not refer to Brunck’s excellent edition of Sophocles published in 1786. As the personalities of the student, translator and scholar emerge, and they are only based upon brief, sample translations and observations, they may or may not be, in part or on the whole, associated with William Blake.

begin page 49 | ↑ back to topIt is possible that Blake may have contributed to some extent at all three of these stages. This may be explained if the manuscript came into his possession at the beginning of his apprenticeship in the early 1770s. In the first instance Blake introduced his series of signatures, including overwriting the (earlier) name Sunderland. In addition, he may have been responsible for making some of the elementary notes, in particular to the Philoctetes. During the 1770s it would be surprising if Blake had not become interested in Philoctetes, especially in relation to Job, as a result of the discussions by Winckelmann, Lessing and Burke and especially upon seeing the distinctive rendering of Philoctetes by James Barry (whom Blake greatly admired) in his etching first produced in 1777 (see illus. 18). William L. Pressly discusses this background in his Life of Barry (1981, pp. 20-26).

Later, during the 1780s, perhaps encouraged by John Flaxman, who was an accomplished student of Greek and Latin, Blake may have developed his knowledge of the classics and spent more time with the manuscript. Flaxman left London for Rome in 1787. This could explain why there is no apparent reference to Brunck’s edition of 1786, or to subsequent scholarship.

Beginning in the late 1790s while working on the manuscript of Vala, and later while living in the cottage at Felpham, Blake evidently renewed his interest in “Greek & Latin.” This interest led to his painting of Philoctetes and Neoptolemus at Lemnos of 1812, an interpretation different from earlier renderings, including Barry’s, and demonstrating the correlations he recognized between the subject of Sophocles’s play and that of the figure of Job.

Alternatively, it would appear more likely that the sketches, translations and notes were in large part present at the time the manuscript came into Blake’s possession. This would explain the apparent absence of reference to scholarship much later than mid century. If Blake did contribute to the translations and notes, and after the turn of the century became the accomplished Greek scholar present in the manuscript, then the apparent absence of reference to Brunck’s and to later scholarship requires explanation. If William Hayley was responsible, and he is an obvious candidate, such scholarship may not have been immediately available and Hayley’s knowledge may not have been up to date.

The specific edition of Sophocles that the manuscript originally interleaved has still to be identified from the offsets. When it becomes known, some of the problems of dating and provenance may be resolved and an explanation found as to why reference to scholarship after 1786 does not appear to be present.

Conclusion

If accepted as authentic, the early signatures make clear that the volume was in Blake’s possession from an early age. The circumstantial evidence which includes Hayley’s letter of 1802, Blake’s of 1803 and his painting of 1812 demonstrate his later interest in learning Greek in general and study of Philoctetes in particular. These help explain why the manuscript was in his possession and at least some of the uses it was put to, whether he contributed largely or not to its contents.

However extensive Blake’s contribution, if the early signatures present in Section III are accepted as authentic, the importance of the Sophocles Manuscript Notebook for our further understanding of Blake is considerable in helping to establish the extent and detail of his intellectual curiosity and its application to his art.

![Οτι ουκ εςτιν ημιν η παλη προς αιμα και ςαρκα,

αλλα προς τας αρχας, προς τας εξȣςιας, προς τȣς

κοςμοκρατορας τȣ ςκοτȣς τȣ αιωνος τȣτȣ, προς τα πνευματικα

της πονηριας εν τοις επουρανιοις. Εφες: 5 [VI] κεφ. 12 [ver.]](img/illustrations/BB209.1.3_Greek.MS.300.jpg)

![measring oer his Steps but late empty, sagacious as Sparta’s Hounds thou trac[es]t

him nor in vain. The Man thou seek[es]t, [h]e [wi]th sweating brow and Hands deep tingd in Blood within his

tent is laid. desist from thy pursuit and tell me why thy [?]course that so my Wisdom may assist thy search.

κυνηγετȣντα - hunting νεοχαραχθ - lately impressed - ευρινος - sagacious εθου.

2 pers. sing. i aor. mid. α τιθημι.](img/illustrations/sophocles-ms-f4r.031.02.bqscan.png)

![Sophocles generally conducts his plays without a prolix prologue. Prologue extended

till the first chorus began. Conclusion of the chorus εξοδος, καταστροϕη. First object -

Fable. Next - Chorus. μελαποια - musick. Οψις - Scenery. Λήμνȣ - . Non te Pœantia proles

Expositum Lemnos nostro cum crimine haberet. Ov. l. 13. The Attic dialect is preserved though out; the Ionic

sometimes however is made use of being so like the old Attic. . . . . . . . hic illa ducis Melibœi Parva

Philoctetæ subnixa Petelia muro. Virg. Æn. 3. l. 401. Ἔνθεν [δὲ] προτέρωςε

παρεξεθεον Μελίβοιαν Apoll. Argon. L 1.592.](img/illustrations/sophocles-ms-f153v.031.03.bqscan.png)