ARTICLE

“In the Darkness of Philisthea”: The Design of Plate 78 of Jerusalem

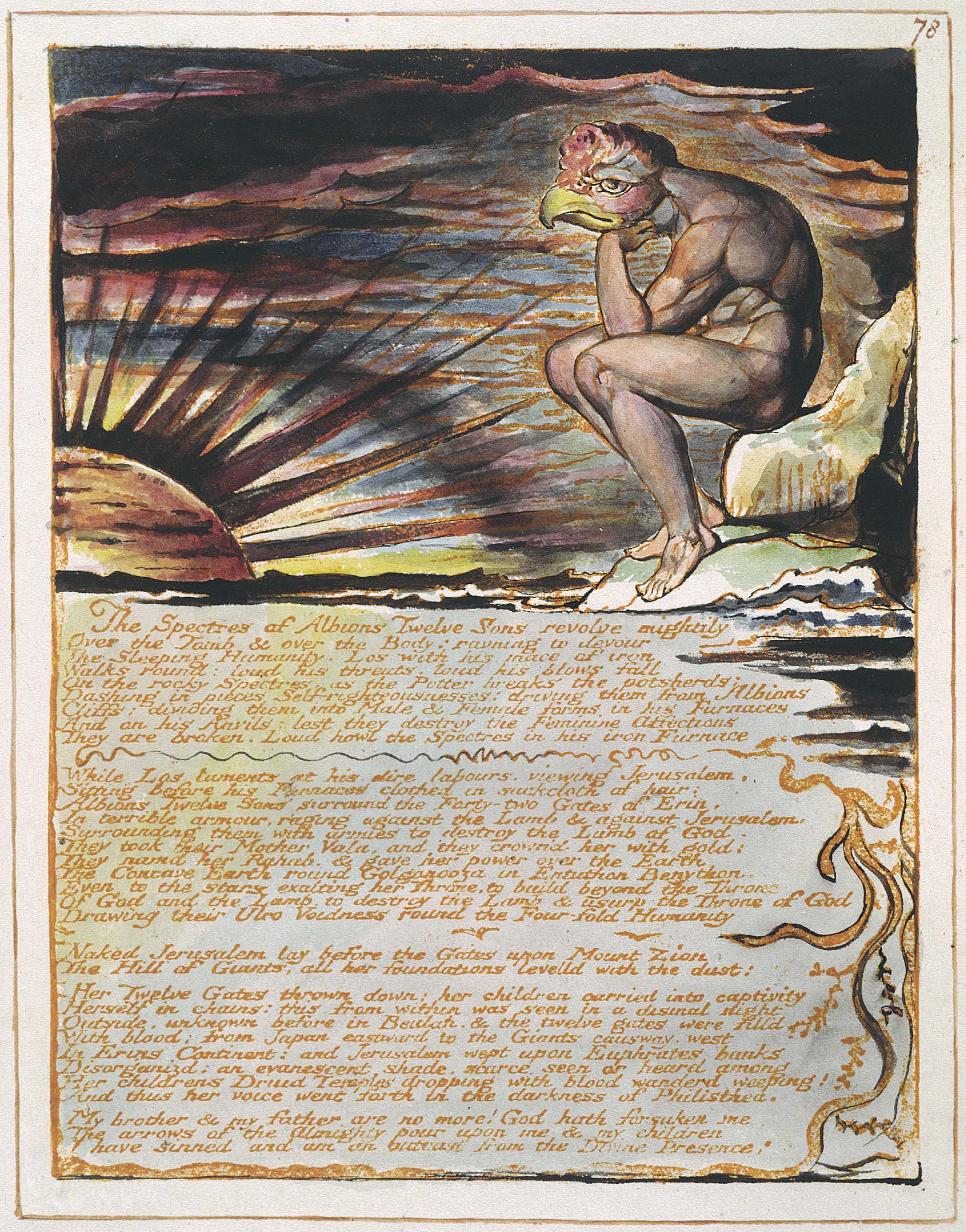

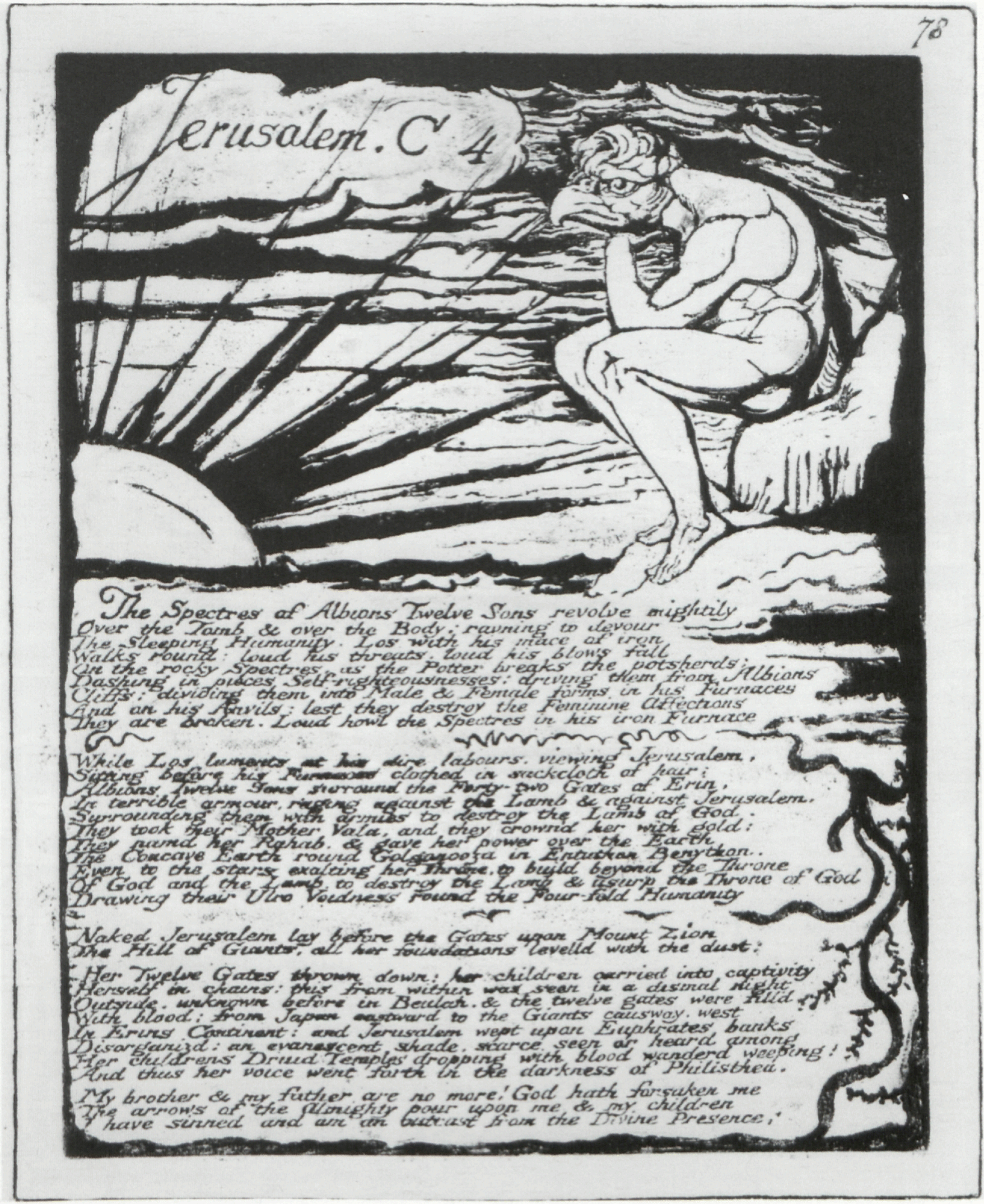

With the hint of a tear in its eye, a hunched figure sits on a cliff sloping towards a dark sea. It has the body of a man and the profiled head of a bird, surmounted by a crest like a cock’s comb, but with a hooked predatory beak like that of an eagle or even a vulture. The bird-head stares gloomily towards the viewer’s left, past a quartered sun appearing on the horizon against the background of a clouded sky. Thus Blake opens the fourth chapter of Jerusalem (see illus. 1 and 2).

The scene on plate 78 of Jerusalem (henceforth J), and especially the figure dominating it, is a controversial one.1↤ 1 Blake texts are quoted from the Erdman edition, cited as E followed by the page numbers. Blake’s illuminated plates other than those of copy E of Jerusalem are cited from Erdman, The Illuminated Blake, referred to as IB followed by the page number. Copy E of Blake’s Jerusalem is discussed with reference to the facsimile edited by Morton Paley. As Morton Paley comments, few of Blake’s images have received more varied interpretations.2↤ 2 Paley summarizes critical opinion in a note to the facsimile edition of Jerusalem, 261. Various identities have been proposed for the figure: Joseph Wicksteed (226), W. J. T. Mitchell (211), Judith Ott (48), W. H. Stevenson (803) and Joanne Witke (180) see him as Los, S. Foster Damon ([1924]473) as Egypt, David Erdman (IB 357) and Henry Lesnick (400-01) as Hand. Erdman, Wicksteed and Lesnick perceive the head as that of a cock; John Beer (253), Mitchell, Witke, Stevenson and Ott see the head of an eagle; Paley ([1983] 89) suggests that Blake was inspired by the hawk-headed Osiris. Opinions differ as to whether the sun in the scene is rising or setting; for instance, while Paley (describing copy E, the unique colored version) sees “an angry sunset” (261) and Erdman (surveying all extant versions) “plainly the setting material sun—a signal for the rising of a more bright sun,” to Beer, looking at the same version as Paley, the sun is “rising in splendour,” and in Witke’s view the bird-headed figure “looks towards a great globe of light reascending on the horizon in expectation of Albion’s redemption.”

Anyone surveying the agglomeration of conflicting critical views may well exclaim, with Blake himself, “But thou readst black where I read white” (E 524). Obviously these are matters on which ultimately readers will have to agree to differ from one another. But I would like, in what follows, to draw attention to one element in the context of this enigmatic image that may have been overlooked: that of “disease”—the “spiritual disease” referred to by the “Watcher” of the vision just preceding, when he directs the poet, as Jesus commanded his disciples, to “cast out devils in Christs name / Heal thou the sick of spiritual disease” (J 77:24-25, E 233).3↤ 3 Matthew 10:8: “Heal the sick, cleanse the lepers, raise the dead, cast out devils . . . .” See also note 13 below. No doubt this adds a further complication to a question already vexed enough, but it may go a little way towards articulating, if not clarifying, some of the ambiguities surrounding this scene.

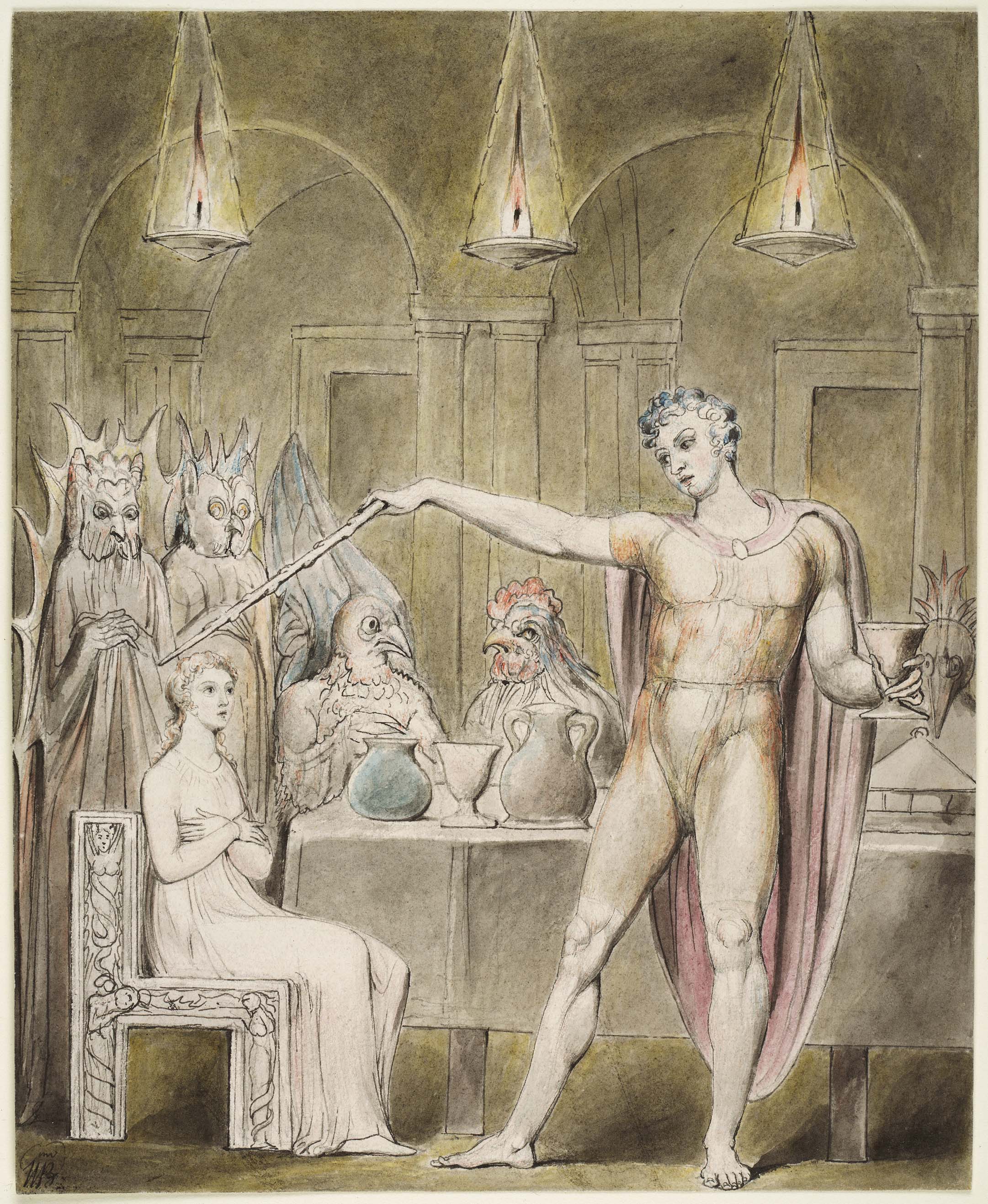

The strongly hooked beak of the bird-head on J 78, the upper part overhanging the lower, suggests that of a predatory bird, like an eagle, or a bird of carrion, a vulture. Amongst the numerous eagles that hover and swoop through Blake’s works are some whose heads can be clearly seen: for instance, on plate 15 of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (IB 112), on plate 3 of Visions of the Daughters of Albion (IB 131), on plate 42 [38] of Milton (IB 258), and in the upper left corner of Blake’s 1805 painting “War” (Butlin, cat. no. 195, pl. 193; and see also cat. no. 189, pl. 195), where the bird (more like a raven or a crow than an eagle) seems to be attracted to carrion flesh. None of these has a crest like the bird-head on J 78—nor, moreover, do the two eagle-headed men riding man-faced bulls in J 46[41]. Blake made several sketches (presumably in 1802) illustrating William Hayley’s ballad “The Eagle” (Butlin cat. nos. 360-63, pl. 467 and 470-72). Two of these (361 recto and 362 recto) show a neck-ruff of raised feathers behind the eagle’s head, but 360 and especially 363, the most advanced of the sketches (tentatively dated by Butlin 1805) show Blake’s usual smooth-headed eagle with a hooked upper beak. Paley (Jerusalem 261) points out that the gryphon pulling the car of Beatrice in Blake’s Paradiso illustration “Beatrice addresses Dante from the Car” (Butlin cat. no. 812 88, pl. 973) resembles the head of the figure in J 78. But I would argue that the way in which the crest is deliberately extended forward in the figure on J 78 to meet the nostrils just above the beak differentiates it from the swept-back crest of the gryphon harnessed to Beatrice’s car. The head of this bird-man is not obviously that of a crested eagle, but something more like a domestic fowl with a crest or comb that suggests (to me, at any rate) a modification of the rooster’s head seen under the right arm of Comus at the banqueting table in Blake’s Comus illustration of c. 1801, The Magic Banquet with the Lady Spell-Bound, from the Thomas set (Butlin cat. no. 527 5, pl. 620) (illus 3).4↤ 4 Pace Judith Ott, who uses this same comparison to support her assertion that the bird’s head in J 78 is not that of a cock (51n1). Blake has given the bird-head in the Comus illustration both the comb and the pendent wattles of a barnyard cock, whereas the beak and lower part of the bird-head in J 78 are definitely eagle-like, having no sign of wattles.

It would be appropriate—as Wicksteed (226) argued—for a cock to figure in the symbolism on this plate. Blake begin page 61 | ↑ back to top

begin page 62 | ↑ back to top

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

“When the cock crew, he wept”—smote by that eyeIn the 1790s Blake had chosen to illustrate these lines with the powerful image of a trumpeting angel commanding the dead to arise.7↤ 7 Bindman, Complete Graphic Works, 348. Blake modified the figure of the angel in this emblem of resurrection and used it again in 1808 on the titlepage of Blair’s The Grave (Bindman, 465).

Which looks on me, on all; that power, who bids

This midnight centinel, with clarion shrill,

Emblem of that which shall awake the dead . . .

(lines 1-4)

Erdman (IB 357) identifies the crest of the figure on Plate 78 as “a cock’s comb—a signal of the morning,” linking it with the dawning of the apocalyptic day of the resurrection of Albion. He also quotes Wicksteed’s association of the image with “the Christian symbol upon Church steeples recalling Peter’s denial of his Lord and the bitter repentance that was to make him the ‘Rock’ upon which the church itself was founded” (226). The sorrowful mien and suggestion of a tear in the eye of the bird-headed man could imply the “bitter repentance” Peter expressed by weeping.8↤ 8 Matthew 26:75, Mark 14:72, Luke 22:62.

Peter’s triple denial of Christ was uttered at the palace of the High Priest, Caiaphas, who had led the chief priests and Pharisees in plotting against Jesus and had counseled them to have him put to death.9↤ 9 Matthew 26:3-4, Mark 14:1, Luke 22:2, and especially John 11:47-53. It was in Caiaphas’s palace, before daylight, that Jesus was arraigned, reviled and buffeted immediately after his betrayal and arrest in the Garden of Gethsemane. Peter, who had followed his master “afar off unto the high priest’s palace, went in, and sat with the servants, to see the end” (Matthew 26:58). He was warming himself at a coal fire “in the midst of the hall” (Luke 22:55) and trying to mingle unobtrusively with the household staff—in effect, he was hoping to pass himself off unnoticed as another of the High Priest’s servitors—when, one after another, three of the servants recognized him as “one of them” (Mark 14:69-70). He responded to each by denying his association with Jesus of Nazareth. He was still within the palace of Caiaphas when he heard the cock crow, for after hearing it he “went out, and wept bitterly.”10↤ 10 Matthew 26:75, Luke 22:62; emphasis mine. The cock and its symbolic crowing can thus also be associated with “Caiaphas, the dark Preacher of Death / Of sin, of sorrow, & of punishment” (J 77:18-19, E 232 [my emphasis]). In fact Caiaphas embodies what Blake elsewhere calls “the infection of Sin & stern Repentance,” a “dread disease” from which “none but Jesus” can save Albion (J 38[43]:75, E 186, J 40[45]:16, E 187). The name “Caiaphas” is given to the “Wheel / Of fire” (J 77:2-3, E 232) of the poet’s vision in the blank-verse lyric on J 77. Its movement “From west to east against the current of / Creation” (J 77:4-5, E 232)—and against the apparent movement of the sun—suggests that in this force opposed to Jesus, this “Wheel of Religion” (J 77:13, E 232) Blake chooses to call by Caiaphas’s name, he approaches the concept of an “Antichrist” in Northrop Frye’s sense of “the form which the social hatred of Jesus creates out of Jesus” (387).

The keynote for the theme of the denial of Jesus is sounded by the quotation from the Acts of the Apostles etched on the previous plate, plate 77: “Saul Saul” / “Why persecutest thou me.” These quoted words of Christ recall that, before he heard them, Saul of Tarsus had set out for Damascus, “breathing out threatenings and slaughter against the disciples of the Lord” (Acts 9:1), intending to suppress the teachings of Jesus and destroy his following. In Blake’s view, the failure to give to the “Mental Gifts” of Genius their due recognition amounts to exactly that—the rejection, persecution and mockery of Jesus:

O ye Religious discountenance every one among you who shall pretend to despise Art & Science! . . . expel from among you those who pretend to despise the labours of Art & Science, which alone are the labours of the Gospel . . . And remember: He who despises & mocks a Mental Gift in another . . . mocks Jesus the giver of every Mental Gift, which always appear to the ignorance-loving Hypocrite, as Sins. (J 77, E 231-32)

The last sentence quoted restates a lifelong conviction of Blake’s, affirmed by a Devil in the final “Memorable Fancy” begin page 64 | ↑ back to top

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

. . . Go to these Fiends of Righteousness . . .

Go, tell them that the Worship of God, is honouring his gifts

In other men: & loving the greatest men best, each according

To his Genius: which is the Holy Ghost in Man; there is no other

God, than that God who is the intellectual fountain of Humanity;

He who envies or calumniates: which is murder & cruelty,

Murders the Holy-one: Go tell them this . . .

(J 91:4-12, E 251)

Through its association with the denial and persecution of Christ, the image of the cock thus hints as well at the begin page 65 | ↑ back to top

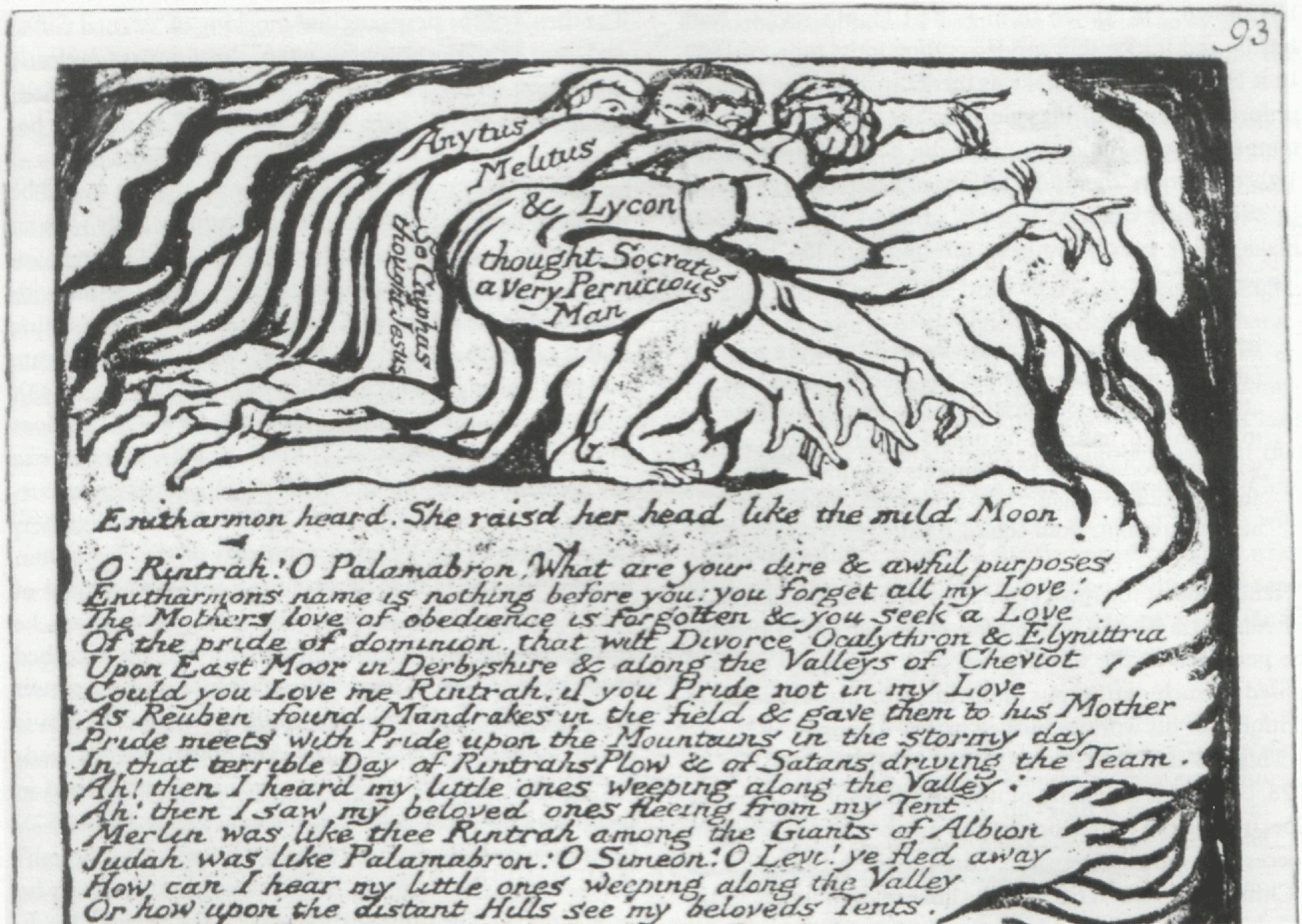

gnawing private anguish Blake suffered because his own work had never achieved the recognition it deserved. Especially during the later period of Jerusalem’s composition, Blake must have agonized over the obscurity and neglect in which his art languished.11↤ 11 Paley comments: “In the circumstances of his life from 1810 to 1818, years which Gilchrist rightly termed ‘Years of Deepening Neglect,’ it must have been difficult for Blake to soldier on with a work which no one might ever buy or even read” (The Continuing City, 6.). In particular, he brooded upon the failure of his exhibition of 1809, and the critical derision it had attracted—notably in the excoriating review by Robert Hunt published in The Examiner in September 1809. Blake was still smarting from that when he executed the later plates of Jerusalem, for in the design of J 93 he explicitly links Caiaphas’s persecution of Christ to the stinging criticism of his own work by Robert Hunt and his two brothers, co-editors of The Examiner (illus. 4). On the upper part of J 93 three male figures bend forward, each with one hand ostentatiously pointing ahead, as though in accusation,12↤ 12 “The Accuser” (or “the Adversary”) translates the Hebrew word “Satan,” as Blake very well knew. The name “Satan” is used in this sense in the Book of Job and elsewhere in the Old Testament. Blake perceived these critics as “accusers” and “adversaries,” the enemies of creative humanity. and the other pointing downward in condemnation. The name of Blake’s “Hand,” who—like Caiaphas—wishes “to Destroy the Divine Saviour” (J 18:37, E 163), is derived from the pointing hand used by the three Hunt brothers as their editorial siglum in The Examiner, and obviously caricatured in this design. Perhaps Blake also associates other “false friends” (“Blakes apology” 12, E 505) with these three figures, on which he has inscribed the words “Anytus / Melitus / & Lycon / thought Socrates / a Very Pernicious Man // So Caiaphas / thought Jesus” (J 93).13↤ 13 The second sentence of this inscription appears on the rear end of the central figure. It is tempting to associate it with Blake’s satirical “apology” in reply to the Hunts’ searing criticism of his Descriptive Catalogue for his 1809 exhibition. Blake’s reply concludes “This is my sweet apology to my friends / That I may put them in mind of their latter Ends” (Notebook 65, E 505). Another vitriolic verse apparently related to this, addressed to “Cosway Frazer & Baldwin of Egypts lake . . .,” ends with the line “And all the Virtuous have shewn their backsides” (Notebook 37, E 505). The latter poem incorporates a reference to Matthew 10:8, the text Blake also quotes in the blank-verse poem of J 77: “This Life is a Warfare against Evils / They heal the sick he casts out Devils . . .” (3-4; Notebook 37, E 505). Though in Jerusalem the context of the quotation is serious, it seems to me that Blake is there concerned with exactly the same issues of betrayal as in the satirical outbursts. The word “Pernicious,” as Erdman begin page 66 | ↑ back to top has shown,14↤ 14 Blake: Prophet Against Empire, 454. is quoted from Robert Hunt’s review, both hostile and intolerably condescending in its tone, of 1809. In it Hunt diagnosed Blake as mentally ill, calling him “an unfortunate lunatic,” his paintings “the ebullitions of a distempered brain,” and the catalogue he published for the 1809 exhibition “the wild effusions of a distempered brain.” In effect Hunt declared that any critic of art who praised Blake’s work must have been infected with his “malady.” He wrote: ↤ 15 Robert Hunt’s comments on Blake and his art are reproduced in full by Bentley 215-18. The historical background is documented and discussed by David Erdman, Blake: Prophet Against Empire, 455-61.when the ebullitions of a distempered brain are mistaken for the sallies of genius the malady has indeed attained a pernicious height, and it becomes a duty to endeavour to arrest its progress. Such is the case with the productions and admirers of William Blake, an unfortunate lunatic, whose personal inoffensiveness secures him from confinement.15“Hand,” one of the most powerfully oppressive of the Sons of Albion, is Blake’s imaginative characterization of what he perceived as the threat to art and indeed to humanity posed by such outrageous Philistinism as that displayed in critiques of his work published in The Examiner.

This is Blake’s concern in the first few lines of the text on J 78. Los wields his “mace of iron,” hitting out at “the rocky Spectres, as the Potter breaks the potsherds; / Dashing in pieces Self-righteousnesses . . . driving them from Albions / Cliffs . . .” (J 78:5-7, E 233). The lines refer to Isaiah 30:14, in which the prophet declares that the Lord will shatter the iniquity of the Children of Israel “as the breaking of the potters’ vessel that is broken in pieces . . . so that there shall not be found in the bursting of it a sherd to take fire from the hearth or to take water withal out of the pit.” The verse Blake recalls is a rebuke to those “which say to the seers, See not; and to the prophets, Prophesy not unto us right things” (Isaiah 30:9-10). Blake’s text, and indeed, his whole book, enact the Lord’s command to Isaiah to issue a warning to those who despise the prophet’s vocation and his message: “write it before them in a table, and note it in a book, that it may be for the time to come” (Isaiah 30:8). The theme of the despising and mocking of “Mental Gifts,” and most of all the prophetic gift of the visionary, is clearly uppermost in Blake’s mind as he sends Los to drive “Self-righteousnesses . . . from Albions / Cliffs” in the text beneath his image of a bird-man perched on those cliffs.

Morton Paley points out, significantly, that “it would be uncharacteristic of Blake to present a human body with an animal head as a positively charged image.”16↤ 16 Jerusalem, 261. Blake’s reading of Milton’s Comus, which he twice illustrated, may well have influenced his basic viewpoint. His second visual interpretation of Milton’s masque was executed c. 1815, while work on Jerusalem was in progress. See especially his rendering of the “ugly-headed monsters” (line 694), Comus’s dissolute followers, in The Magic Banquet with the Lady Spell-Bound, in the versions of both c. 1801 (reproduced above) and c. 1815 (Butlin, cat. no. 528 5, pl. 628). The scene on J 78 is filled with “negatively charged” signs. I agree with Paley and those others who maintain that the sun is setting in this scene. Twice in the text on subsequent plates we are told that “the night falls thick” (J 83:61, E 242, 84:20, E 243), and when Los walks amongst his Furnaces at J 85, he does so “in the deadly darkness” (J 85:10, E 244). Perhaps, like the “Wheel of Religion,” this sun is moving “against the current of / Creation”; and perhaps Blake intended the gathering darkness to be the ironic antithesis of the “light from heaven” (Acts 9:3) that miraculously surrounded Saul of Tarsus when, at high noon on the road to Damascus, he heard the voice of Jesus uttering the words Blake inscribed at the head of J 77. In copy E the atmosphere of the sunset is not peaceful and luminous, but threatening. The sun is circled by a black aura, and Blake even obliterated the heading “Jerusalem. C 4” that appears against a white cloud in the black-and-white copies (for instance copy D, IB 357), painting over it in dark purplish-black tones, “as though” Erdman comments, Blake “did not want anybody to be sure” (IB 357). The sun’s disk in copy E is flecked with black, contributing to the pervading gloom reflected in the birdman’s sorrowful, even agonized, “expression” as he looks back on the preceding three-quarters of the work: for the quarter of the sun visible on the horizon here also represents the last quarter of the epic Jerusalem that is about to unfold.

The darkness and generally oppressive atmosphere could be attributed to the association of the cock with the denial of Christ. A human figure with a head suggesting that of a cock, herald of the dawn and symbol of resurrection, sadly, or angrily, contemplates a sun that appears to be setting, when, according to tradition, the cock should look toward the rising sun.17↤ 17 Lesnick rightly describes the design as “basically ironic. The cock’s comb might suggest . . . that the figure is announcing the rising of the sun. In fact, the sun at the left is setting, and the setting of the sun marks the beginning of the deepest night of Ulro” (400). But it seems to me that another factor enters into the image as well: one that expresses the concept of the “spiritual disease” which the poet is commanded to heal in the blank-verse lyric on J 77, and at the same time begin page 67 | ↑ back to top lashes back at the diagnosis of mental illness that Robert Hunt had applied broadly both to Blake and his art in his review of 1809. Perhaps, in one quite basic strand of meaning, Blake asserts that his detractors were “cock-brained” in their judgement.18↤ 18 O.E.D. “Cock-brained: a. Having little judgement, foolish, lightheaded.” The latest example of usage is dated 1856.

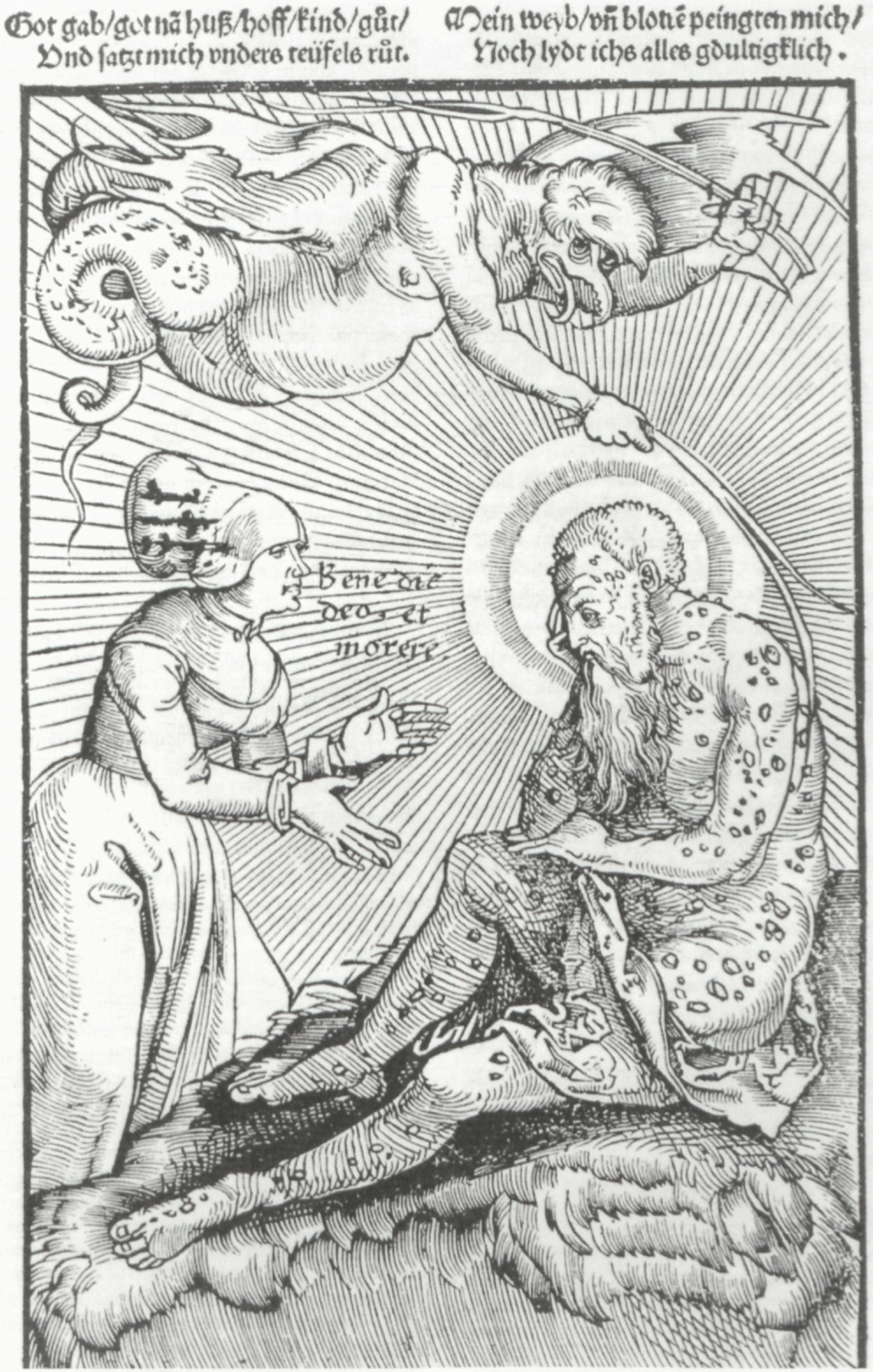

Blake’s design on J 78 has certain features in common with an illustration in a sixteenth-century medical text, Feldtbůch der Wundartzney, by Hans von Gerssdorff, a physician of Strassburg. I offer this illustration as a parallel only, since although it is well known that Blake was drawn to old alchemical and scientific texts, valuing especially their emblems and illustrative material,19↤ 19 Kathleen Raine offers multiple instances of Blake’s interest in such writings in Blake and Tradition. I have no means of proving that he ever saw this particular work. But neither have I any doubt that he saw and noted pictorial representations like this one, which is “generic” in its nature, as I will explain.

The first edition of von Gerssdorff’s work was published in Strassburg by Joannẽ Schott in 1517. It was well enough received to run into at least one subsequent edition, which appeared in 1532.20↤ 20 The version I have used for reference is a facsimile of the first edition (1517), reproduced from two original copies, one in the Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg, and the other in a private collection. I have also consulted a microfilm of a copy of the 1517 edition in the British Library in London. The illustration I discuss appeared in both the 1517 and the 1532 editions. Though the work is divided into numbered sections, the printer did not number individual pages. I am especially indebted to Professor Hildegard Stielau of the Department of German of the Rand Afrikaans University, Johannesburg, for translating, and for her scholarly guidance in reading, parts of this work. My thanks are due as well to Dr. Michael Milway, Curator of the Center for Reformation and Renaissance Studies at the E. J. Pratt Library of Victoria University, University of Toronto, for his patient assistance in providing information and a photograph. The work is plentifully illustrated with woodcuts. Many of these show, with a degree of scientific accuracy, anatomical dissections, surgical instruments, and parts of the human body being subjected to their use by contemporary surgeons attempting to repair injuries, especially those received in battle. This category of illustrations may well have been “specific,” printed from blocks prepared especially for this work. But other illustrations seem to be “generic,” related in only a general manner to the text—for instance, the handsome frontispiece illustration showing the patron saints of medicine, Cosmas and Damian. The illustration I wish to discuss seems to fall into this second category. It appears in the third “Tractat” of the work, in a section of the text dealing with leprosy, but actually shows a victim of either smallpox or syphilis.21↤ 21 Jolande Jacobi (xiii; see note 24 below for reference) suggests that the disease represented may be syphilis; Hildegard Stielau (personal communication) believes that the word “blonẽ”[e] in the couplet on the frame (discussed in the body of this essay) may indicate that whoever composed the couplet believed that the personage in the picture was afflicted with smallpox. The consensus is that the disease depicted in the illustration is not the one discussed by von Gerssdorff in the surrounding text. It seems unlikely that this respected physician, who evidently wrote from extensive practical experience, would have confused leprosy with the symptoms and development of these other two diseases, both all too familiar at the time—which implies that the choice of illustration was not the author’s but (probably) the printer’s, and that it was not put in to illustrate a specific scientific point. This illustration, like the frontispiece portrait of Cosmas and Damian, may also have been used by the same or another printer in other books (a practice not uncommon at this period), and in contexts not necessarily medical.

Von Gerssdorff describes in detail the manifestations of various forms of leprosy, drawing heavily on such standard authorities as Galen, Avicenna, Averroes and Gordonius. He makes it clear that the physician can do little or nothing for the patient suffering from this affliction, beyond amputating members of the body that have become gangrenous in the course of the relentless degeneration characteristic of the disease. Though von Gerssdorff himself eschews philosophic reflections, his illustrious contemporary Paracelsus (with some of whose writings Blake had long been familiar22↤ 22 S. Foster Damon writes that Blake found in the works of Paracelsus “a preliminary sketch of his own universe” (Damon [1973], 322). In a poetic recapitulation of major influences in his own intellectual development, Blake implies that he first read Paracelsus before “the American War began”—that is, prior to 1776 (Letter to Flaxman, 12 September 1800, lines 7 and 9, E 707-08). See note 24 below. ) reminds both physician and patient that such a disease must be regarded as a scourge of God. Paracelsus articulates a widely held view that accords with Marsilio Ficino’s concept of the “priest-physician”23↤ 23 See Désirée Hirst’s account of Ficino’s influence on Paracelsus in chapter 2 of Hidden Riches (44-75). when he divides the diseases of man into “those which arise in a natural way, and those which come upon us as God’s scourges.” For, he admonishes his colleagues, ↤ 24 Paracelsus, Sämtliche Werke. II. Abteilung. Die theologischen und religionsphilosophischen Schriften. Ed. Karl Sudhoff and Wilhelm Matthiessen. Vol. 1. (Munich: O.W. Barth, 1923) 12: 226. Trans. Norbert Guterman in Selected Writings, ed. Jolande Jacobi, 81. Most of the major philosophical, medical and alchemical writings of Paracelsus had been translated into English in the latter half of the seventeenth century. There was widespread interest in them in England at this time, as there also was in the works of Jakob Boehme. Blake was equally interested in Boehme’s work and also read it in seventeenth-century translations. Two of Paracelsus’s works in translation that Blake is likely to have read are listed below under Works Cited. Jacobi uses the woodcut under discussion, reproduced from the 1532 edition of von Gerssdorff’s book, to illustrate the passage from Paracelsus cited in my text.

God has sent us some diseases as a punishment, as a warning, as a sign by which we know that all our affairs are naught, that our knowledge rests upon no firm foundation, and that the truth is not known to us, but that we are inadequate and fragmentary in all ways, and that no ability or knowledge is ours.24begin page 68 | ↑ back to top

Opposite the beginning of von Gerssdorff’s section on leprosy, the printer has placed a woodcut showing a sufferer who evidently represents the biblical Job, sitting on a hillside that slopes quite sharply down from right to left (illus. 5). He is seen in profile on the viewer’s right, facing into the picture, in an attitude comparable to that of Dürer’s Melencolia I and of Blake’s bird-man (illus. 6).25↤ 25 Samuel Palmer, who visited Blake often in the rooms at Fountain Court in which he and his wife lived after 1821, recalled that Blake kept a print of this work “close by his engraving table” (Bentley 565n3). Judith Ott (49) first pointed out the parallel between the pose of Dürer’s “melancholy angel” and Blake’s bird-man; but see Hirst’s discussion of the contextual significance of Dürer’s image (44-48). His right leg is bent, with his right elbow resting on it, left hand under the right elbow, head slightly bowed and resting against his right hand. He has no covering apart from a cloth draped across his loins, revealing that his whole body is covered with blisters. Above his head a creature resembling a cockatrice hovers on dragon-like wings. This “teüfel” has the head of a rooster, with the thin, sharply hooked beak of a fighting-cock or even a predatory bird. It has the tail of a dragon or serpent, but its trunk with sagging belly and its muscular arms and hands are those of a man. The creature grasps in each hand a long, bifurcated whip or scourge. It is engaged in lashing the hapless victim on his back with the scourge held in the right hand, while that in the left hand is drawn back to follow up swiftly with another cut. (The attitude of the partly serpentine “teüfel” and its positional relationship to its victim suggest those of Blake’s serpent-entwined Satanic “Elohim” in his painting “Job’s Evil Dreams,” c. 1805-06 [illus. 7].26↤ 26 Butlin cat. no. 550 11, pl. 707. ) The victim’s wife stands before him at the viewer’s left, primly elegant in a tight-sleeved high-necked dress and elaborate headgear. She piously urges her husband “Benedic deo, et morere”—“Bless God, and die.” Job’s wife gave her husband this advice when the Lord afflicted him “ulcere pessimo, a planta pedis usque ad verticem eius”—“with a very grievous ulcer, from the sole of his foot even to the crown of his head” (Job 2:7-9). At the top of the engraving two couplets are inscribed (no doubt by the printer), in German.27↤ 27 Many of the other woodcut illustrations are surmounted by couplets in a similar tone, though those showing surgical procedures and instruments usually have explanatory prose inscriptions, in German. In the first of these the victim speaks, in a loose translation of Job 1:21, saying “Got gab / got nã[e] huss / hoff / kind / gůt[e] / // Und satzt mich unders teüfels růt” (“God gave / God took away / property / children / goods // And set me under the devil’s rod . . .”), while in the second he refers to his wife’s additions to his sufferings—implying the context of the quotation included within the frame of the illustration: “Mein weyb / uñ[e] blonẽ[e] peingten mich // Noch lydt[e] ichs alles gdultigslich”— “My wife / and my blisters afflict me // Yet I suffer all things in patience.” The artist has emphasized this saintly submission by surrounding the sufferer’s head with a double aureole, extending all the way to the border of the engraving on all sides. The visual effect is that of a sun, whose center is the profiled face of the sick man.

My guess is that this design was produced originally to illustrated a text of the Book of Job. Blake, whose preoccupation with the Book of Job extended throughout his creative life,28↤ 28 Blake’s earliest Job illustrations date back to c. 1785; the latest, the set of engravings commissioned by John Linnell, were executed in 1825, shortly before his death. Quotations from, and echoes of, the Book of Job abound in Blake’s works from the earliest extant fragments to Jerusalem. would have paid attention to such a representation in any context because of these specific associations. Kathleen Raine notes: “From an early stage Blake seems to have identified the sickness of Albion with the sickness of Job,” and quotes from The Four Zoas, Night the Third, p.41, lines 15-16 (E 328): “the dark Body of Albion left prostrate upon the crystal pavement / Coverd with boils from head to foot.”29↤ 29 Blake and Tradition 2: 256.

To return to J 78: one element of Blake’s creation is undoubtedly, I believe, the Christian emblem of the cock. On the one hand it stands for the affirmation of life, since it utters “that Signal of the Morning” of resurrection, here implied only through ironic association. On the other hand, the cock can represent the denial of Jesus “the bright Preacher of Life” (J 77:21, E 232) by those hypocrites who claim to follow him, but actually serve “Caiaphas, the dark Preacher of Death” (J 77:18, E 232). But I suggest that another element of Blake’s composite figure may be represented by the monstrous cockatrice, which yet is partly human—for he is an aspect of “the Antichrist accursed . . . a Human Dragon terrible” (J 89:10-11, E 248). The creature embodies the “infection” transmuted by Blake from a physical to a “spiritual disease” (J 77:25, E 233), the “infection of Sin & stern Repentance” (J 38[43]:75, E 186). It is a scourge that causes the sufferer to long for death. If Blake did have in mind an emblem like the one included in von Gerssdorff’s book, then he replaced the head of the seated personage with that of his cockatrice-like persecutor—thus casting the victim in the role of the disease itself—and removed the sun-like aureole from the head of the sufferer in order to place it on the horizon. Paracelsus wrote: “The imagination is . . . the sun of man . . . It irradiates the earth, which is man. . . .”30↤ 30 Paracelsus his Archidoxies (London, 1661), quoted by Damon (1965) 322. The sun in the scene on J 78 becomes a symbol of man’s diseased imagination, sinking in an aura of deep melancholy and about to be engulfed by “the darkness of Philisthea” (J 78:30, E 234), from which the voices of both Jerusalem and the artist William Blake are heard lamenting. In the blank-verse poem on the preceding plate, a heavenly “Watcher” commands the poet to heal those afflicted begin page 71 | ↑ back to top with this “spiritual disease.” The “Holy-One” who guided the prophet Daniel (Daniel 4:13) and has now come to instruct the poet foresees that, through the “self-denial & forgiveness of Sin” (J 77:23, E 232) preached and practiced by Jesus, Albion may be cured of the moralistic malaise bringing down all the “seven diseases of the Soul” (the traditional “Seven Deadly Sins”) that “settled around [him] . . . as he builded onwards / On the Gulph of Death in self-righteousness” (J 19:26-27, 30-31, E 164). The diminishing sun in the scene on J 78 sets beneath a “dark incessant sky” as the bird-man contemplates the “Gulph of Death” (J 19:22, 31, E 164).31↤ 31 Perhaps Blake associated the dark expanse of sea over which the bird-man gazes with the “Sea of Rephaim” which eventually “oerwhelm[s] . . . all” in the revelation of the “Covering Cherub” on J 89:50-51, E 249. Since this overwhelming “Sea” extends to “Irelands furthest rocks where the Giants builded their Causeway,” the bird-man of J 78 may be looking westwards across the Irish Sea (the “Giant’s Causeway” is on the north coast of Antrim, Ireland). There is no mention of a “Sea of Rephaim” in the Bible (as Stevenson points out [829]), but since Philistines encamped repeatedly in the Valley of Rephaim (2 Samuel 5:18, 22 and 23:13), Blake may have coined the phrase to describe the invasion of Philistinism. Blake is pessimistically viewing the whole scene at this moment as the landscape of “Philisthea.” The bird-headed figure is both Philistine “ignorance with a rav’ning beak!” (J 19:13, E 152) and the “ignorance-loving Hypocrite” persistently misrepresenting “Mental Gift[s] . . . as Sins” (J 77, E 232), who compels Jesus to die on the cross just as surely as did Caiaphas at the head of his council of “Crucifying” Pharisees (J 77:28-30, E 233). The figure on J 78 embodies the “disease forming a Body of Death around the Lamb / Of God, to destroy Jerusalem & to devour the body of Albion” (J 9:9-10, E 152). In copy E the malaise seems to erupt on the sun’s disk in black marks suggestive of the plague-sores covering the body of the suffering Job-figure in von Gerssdorff’s book. The sick sun reflects the “corruptibility” that Los sees upon the limbs of Albion (J 81:84 - 82:1, E 241), the “spiritual disease” the poet is called upon to heal by revitalizing the imagination, which Blake identified with Jesus.32↤ 32 “The Eternal Body of Man is The IMAGINATION./God himself/ that is / The Divine Body / Y’shu’a JESUS we are his Members” (Blake, The Laocoön, E 273). Like other contemporary accounts of leprosy, von Gerssdorff’s description of the disease defines its symptoms conventionally in terms of the medieval theory of humours, and stresses repeatedly the physical and psychological role of “melancholy” or “black bile” in the development and progress of the illness. For Blake too, as both Ott and Mitchell have observed, “melancholy” is a notable theme of the scene on J 78.

Albion is still “sick to death” as Blake opens this fourth chapter of his epic (J 36 [40]:12, E 182). He suffers “the torments of Eternal Death” (J 36 [40]:25, E 182), dying piecemeal like the miserable leper whose physical deterioration the good doctor of Strassburg records in ghastly detail in his text. The “Watcher” from heaven calls upon the poet himself on J 77 to assume an apostolic and prophetic role like that of Peter and later Paul, “in Christs name” to “cast out [the] devils” that scourge Albion in his afflicted state, to “heal” the inhabitants of Albion of their “spiritual disease” (J 77:24-25, E 233). On J 78, Albion has not yet achieved the condition prophetically enacted on the chapter divider, J 76, in which he stands in the darkness of his benighted island before Jesus, crucified upon the “deadly Tree . . . [of] Moral Virtue” (J 28:15, E 174), and takes upon himself Christ’s divine humanity.33↤ 33 See Paley’s summary of conflicting critical interpretations of J 76 in The Continuing City, 113-18. Paley’s own conclusion, which I completely accept, is that “the ‘naïve’ view of this picture, deriving from its immediate affect, fully accords with the central doctrine of Jerusalem . . . which we find almost everywhere in Blake’s works. ‘Therefore God becomes as we are, that we may be as he is’ (There is No Natural Religion [b], E 2) . . .” (117). See also Mitchell, 209-11. But J 76 is a “visionary study.” On J 78, Blake shows us symbolically the actual situation at this pivotal point of his epic. Albion at this moment is “shrunk to a narrow rock in the midst of the sea” (J 79:17, E 234) and is dominated—in fact, literally “sat upon”—by “Self-righteousnesses” (J 78:6, E 233), epitomized in the monstrous figure of the bird-headed man, “Self-righteousness / In all its Hypocritic turpitude” (Milton 38 [43]:43-44, E 139). As Caiaphas himself may have contemplated the dawning of that Friday on which he knew with certainty that the forces he had set into motion were to bring about the death of Jesus, so this figure contemplates a horizon on which a sun that should be rising as a bright source of life and light appears to be sinking into “deadly darkness.” The parallel is an exact one. The bird-headed man embodies everything that Caiaphas, as the summation of the forces opposing Jesus, represents for Blake: the Pharisaic hypocrisy, and the Philistinism, of individuals who—like Saul of Tarsus and Robert Hunt—zealously persecute the spiritually gifted and vilify “Mental Gifts” like Blake’s own, “which always appear to the ignorance-loving Hypocrite as Sins.” These are all to “become One with the Antichrist” (J 89:62, E 249). Blake may well, as Erdman asserts, have meant this figure to represent “the sons of Albion . . . condensed . . . into Hand, with ‘rav’ning’ beak” (IB 357). But he also incorporates Caiaphas, the predator who preys on creative—which is to say, meaningful—human life, “ravning to devour / The Sleeping Humanity” (J 78:2-3, E 233). He embodies the “spiritual disease” of self-righteous morality from which Albion yet suffers, and expresses the immobilizing “melancholy” which is one of its most destructive symptoms throughout the epic Jerusalem.34↤ 34 Compare J 36 [41]:59-60, E 183. The same melancholy afflicts the artist of genius whose gifts are reviled and refused recognition—by which Jesus the Savior is denied as Peter denied him in a fearful, though in his case momentary, fit of the “Hypocritic begin page 72 | ↑ back to top

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

True enlightenment will come—both the cock as an emblem of the sunrise and St. John’s eagle with its apocalyptic associations imply that the “New Age” will dawn at last. So, towards the end of his life, Blake was to reassure a future audience, and himself, in an inscription on his engraving of “Job’s Evil Dreams” (1825): “the triumphing of the wicked is short, the joy of the hypocrite is but for a moment” (Job 20:5).35↤ 35 William Blake, Illustrations of the Book of Job (London, 1825) 11; reproduced by Bindman, pl. 636. By hinting at the visionary evangelist whose symbol was the eagle, the bird-man asserts the visionary and prophetic role of the artist. And even though the figure in J 78 sits before a sun that appears, ironically, to be setting, Blake implies a latent hope by suggesting the positive symbolic aspect of the cock, whose call signalled the awakening to renewed life: “England! awake! awake! awake!” (J 77:1, E 233). It is this hope of spiritual renewal that Blake is to display as fulfilled in his prophetic conclusion to Jerusalem, when the diseased “Body of death” is driven out, and all the birds and beasts in his broad range of symbolism “. . . Humanize / In the Forgiveness of Sins” (J 98:20, 44-45, E 257-58).

Works Cited

Beer, John. Blake’s Visionary Universe. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1969.

Bentley, G.E. Jr. Blake Records. Oxford: Clarendon, 1969.

Biblia Vulgata. Madrid: Biblioteca de Autores Cristianos, 1965.

Bindman, David, comp. The Complete Graphic Works of William Blake. Assisted by Deirdre Toomey. London: Thames and Hudson, 1978.

Blake, William. The Notebook of William Blake. A Photographic and Typographic Facsimile. Edited by David V. Erdman with the assistance of Donald K. Moore. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1973.

—. The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake. Ed. David V. Erdman, commentary by Harold Bloom. New York: Doubleday, 1988.

Butlin, Martin. The Paintings and Drawings of William Blake. 2 vols. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1981.

begin page 73 | ↑ back to topDamon, S. Foster. William Blake: His Philosophy and Symbols, 1924. Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1958.

—. A Blake Dictionary. 1965. Ed. Morris Eaves. London: Thames and Hudson, 1973.

Erdman, David V. Blake: Prophet Against Empire. 3rd ed. New York: Dover Publications, 1977.

—. The Illuminated Blake. London: Oxford University Press, 1975.

Erdman, David V. and John E. Grant, eds. Blake’s Visionary Forms Dramatic. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1970.

Frye, Northrop. Fearful Symmetry. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1947.

Hirst, Désirée. Hidden Riches. London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1964.

Holy Bible, Douay-Rheims translation. Birmingham: C. Goodliffe Neale, 1955.

Holy Bible, King James Version. New York: American Bible Society, 1967.

Lesnick, Henry. “Narrative Structure and the Antithetical Vision of Jerusalem.” In Blake’s Visionary Forms Dramatic, 391-412.

Milton, John. The Poems. London: Longman, 1968.

Mitchell, W. J. T. Blake’s Composite Art: A Study of the Illuminated Poetry. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1978.

Ott, Judith. “The Bird-Man of Blake’s Jerusalem.” Blake 10 (1976): 48-51.

Paley, Morton D. The Continuing City. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983.

—, ed. Jerusalem. By William Blake. London: William Blake Trust / Tate Gallery, 1991.

Paracelsus. Selected Writings. Ed. with an Introduction by Jolande Jacobi. Trans. Norbert Guterman. Bollingen Series 28. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1951-1988.

—. Archidoxes. Trans. J.H. [?James Howell]. London, 1661. 2 parts.

—. Philosophy Reformed & Improved in four Profound Tractates. Trans. R. Turner. London, 1657.

Raine, Kathleen. Blake and Tradition. Bollingen Series 35:11. 2 vols. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1968.

—. “The Crested Cock.” Blake Newsletter 1 (1967-68): 9-10.

Stevenson, W. H., ed. Blake: The Complete Poems. 2nd ed. London: Longman, 1989.

von Gerssdorff, Hans. Feldtbůch der Wundartzney. Strassburg: Joannẽ Schott, 1517. 2nd ed., 1532. Facsimile of 1517 edition reproduced for Editions Medicina Rara Ltd. under the supervision of Agathon Presse, Baiersbronn, West Germany, 1970.

Wicksteed, Joseph. William Blake’s Jerusalem. London: Trianon Press, 1954.

Witke, Joanne. William Blake’s Epic: Imagination Unbound. London: Croom Helm, 1986.

![MELENCOLIA I

VIIII X XI XII I II III IIII V

16 3 2 13

5 10 11 8

9 6 7 12

4 15 14 1

15[14]

AD](img/illustrations/duerer-melencolia-i.032.03.bqscan.png)