review

William Blake. Zwischen Feuer und Feuer. Poetische Werke. Zweisprachige Ausgabe. Trans. Thomas Eichhorn. Afterword by Susanne Schmid. München: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, 1996. Pp. 501.

William Blake. Milton. Ein Gedicht. Trans. Hans-Ulrich Möhring. Wien-Lana: edition per procura, 1995. Pp. 294.

These new translations offer German readers two distinct perspectives on Blake’s work, each valuable in its own way. Zwischen Feuer und Feuer (Between Fire and Fire) is a bilingual edition of all of Blake’s shorter illuminated works, as well as Poetical Sketches, The Everlasting Gospel, and the notebook poems and fragments. These are collected in a moderately priced paperback volume appropriate for university courses as well as for the general reader. The aim, on the whole, is to render Blake accessible to non-specialists; thus, both the English texts and the translations follow the regularized spelling and punctuation of Alfred Kazin’s 1946 Portable Blake. There are 18 black and white reproductions, and an appendix provides basic notes on dates of composition and difficult vocabulary, along with a chronology of Blake’s life, a list of further reading, and a brief afterword.

Susanne Schmid’s afterword to Zwischen Feuer und Feuer offers a concise, balanced account of Blake’s earlier works in biographical and historical context. Schmid introduces Blake by way of an effective contrast between two of his most famous images: the revolutionary energy of Albion Rose and the ambiguous creativity of The Ancient of Days (the cover illustration for this edition). Correlating these two aspects of Blake’s character with his radical and revolutionary context on the one hand, and his ethics and aesthetics on the other, Schmid outlines brief readings of several poems which, while uncomplicated, maintain a good balance between the historical and the visionary. The strong historicist concerns of the essay are reinforced by Schmid’s allusions to the place of the current volume in the twentieth-century reception of Blake in Germany. Beginning with the first substantial German translation in 1907 and incorporating the pop-culture Blake of Allen Ginsberg and Jim Morrison, this reception history reached a high point in 1958, when three translations appeared at once: two published in West Germany and presenting a lyrical Blake, the other published in the GDR and presenting Blake as a political revolutionary. It would have been interesting to hear more about the contrasting reception of Blake in the two Germanys, especially since the

present translation apparently aims at a new marriage of the political and the lyrical.The translations, especially of lyric poetry, sound good. Thomas Eichhorn has effectively retained the rhyme and rhythm of Blake’s lyrics while providing mainly literal translations. Some of the ambiguities survive very nicely in the German, as in the last lines of the “Innocent” “Chimney Sweeper” and “Holy Thursday,” which in German as in English come across as comfortingly proverbial in rhythm, yet ominous in context and significance: “Wer stets seine Pflicht tut, dem wird auch kein Harm” (51) or “Hegt Mitleid, daß ihr nicht die Engel von der Türe jagt” (59). Other ambiguities inevitably get lost, as with the “stain’d” and “clear” of the line from the “Introduction” to Songs of Innocence that has figured in so many revisionary readings of the Songs. “And I stain’d the water clear” gets flattened here to “Und ich färbt’ das Wasser dann” (39), which is indicative of an occasional tendency to make do with a filler word like dann ‘then’ for the sake of rhythm and rhyme. Eichhorn’s translations of the prophetic poems work quite well as adjuncts to the facing-page English text, even if not every word and every letter is put into its fit place. At the beginning of The Book of Urizen, for instance, it is unclear why a single one of the verbs on plate 1 has changed from past to present tense (“Some said” as Manche sagen, rather than Manche sagten [335]).

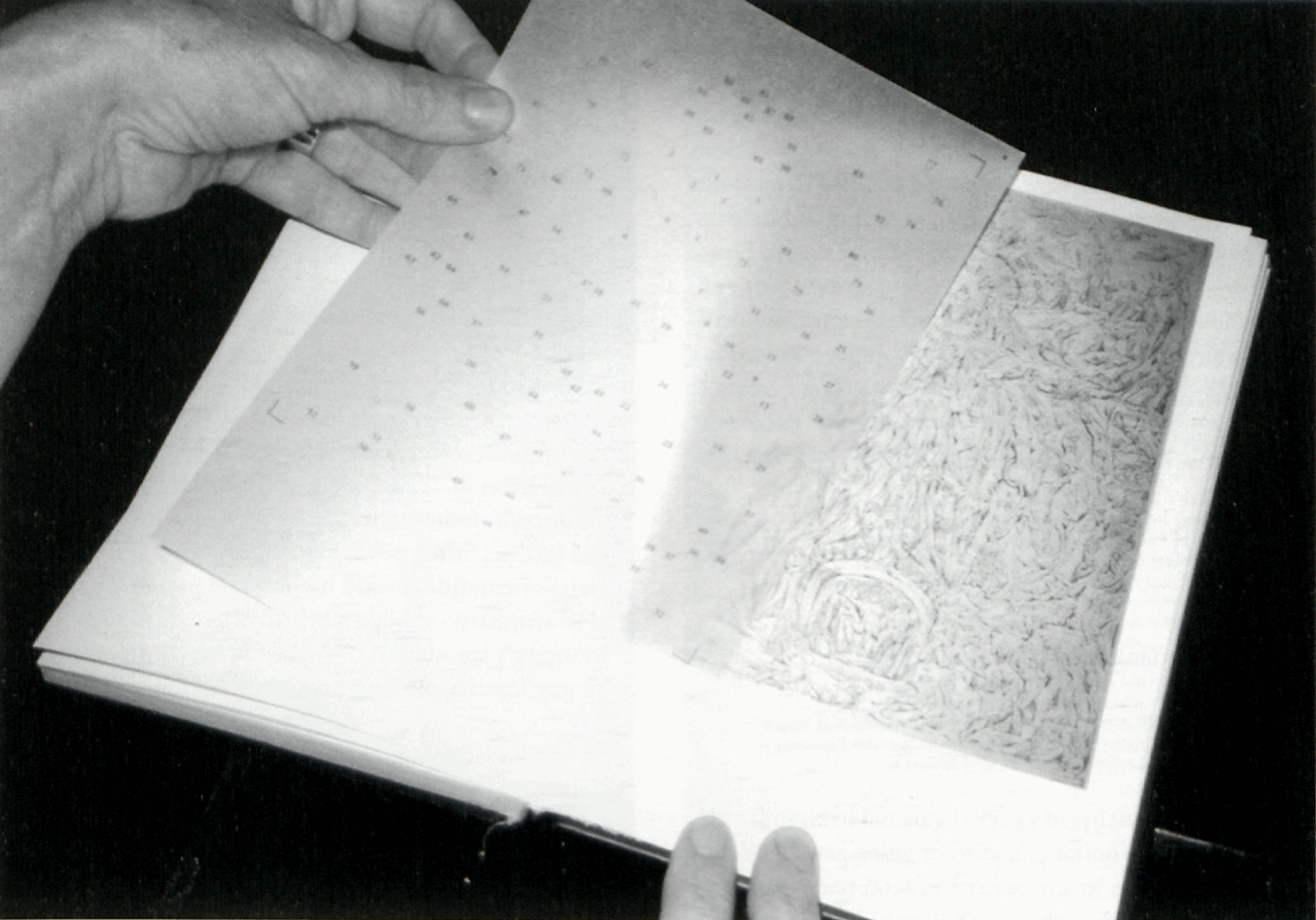

begin page 25 | ↑ back to topThe hardcover translation of Blake’s Milton published by the small Viennese press “edition per procura” tells a different story. This is a passionate labor that, like the English edition of Milton published by Shambhala/Random House in 1978, has spiritual education as its aim. It begins with a full reproduction of copy D of Milton, with text plates in black and white and full-page designs in color, followed by the German translation, followed by an interpretive essay and notes that together comprise more than half the book. The volume ends with a reproduction of The Last Judgment and a translation of Blake’s “Design of The Last Judgment”; the translator tries to correlate Blake’s description with the drawing by means of a transparent overlay and numbers identifying specific figures in that crowded design (see illus. above).

This is a first-time German translation of Milton—indeed, of any of Blake’s major prophecies. Hans-Ulrich Möhring has been working for several years on a complete German translation of Blake’s work; he has evidently thought long and deeply about his subject, and his interpretation and commentary, as well as the translation, reflect an intense engagement with the poem and with Blake criticism in English. He aims to provide the reader with a guide to Milton that, as he says, he would have liked to have had while translating, but in fact had to work out for himself during the translation process. He hopes the commentary will awaken in the reader “a feeling for the weave of this poem and its peculiar denseness and—yes—even its beauty” (186).

Möhring’s long interpretive essay begins with observations and comparisons that, by way of numerous quotations from Hölderlin, a Kantian epistemological framework, and some Heideggerian formulations, insert Blake into a European tradition of poetry and philosophy—not so much by scholarly hypothesis and demonstration, but through the response of a German reader who has been profoundly touched by Blake’s art. Möhring believes that direct experience of Blake’s texts is the only way to come to an understanding of them. As he says, the only value of an interpretation is “whether it helps us read—helps us allow the poem to approach”; the poem must not be “banished into. . . artificial spaces for art, in which experts apply themselves to expert problems, and fail to notice that life itself is at stake” (171-72). In other words, what is at stake here is not simply a translation of Milton from English into German, nor from poetry into comprehensible concepts or facts, but rather a translation of readers themselves into “visions of eternity” begin page 26 | ↑ back to top

through a regeneration of their perceptive faculties (172). Möhring works through the development of Blake’s thought by way of his response to the Bible and his revision of Paradise Lost, providing an intellectual biography of Blake that traces the development of his philosophy through numerous early works. Fifty pages later, the last sentence of the interpretive essay summarizes Möhring’s view of Blake:Perhaps, after almost 200 years, we may observe that in William Blake a poet arose who experiences the truth of Europe’s grand mythos—the birth of the child, the incarnation of God, the death of God, the resurrection of the human out of the fragmentation of the four points of the cross, the imitation of Christ, the birth of the free individual image of God out of the dark dragon’s belly of a long history—and who thereby also, as myth, tears it apart. (180-81)

While clearly achieved through personal experience and study, Möhring’s 84-page, plate-by-plate commentary on Milton contains few surprises for Blake scholars. It develops a now-classic reading of the poem in terms of biblical allusion and revision, Blake’s reaction against materialist philosophy, a revolutionary and apocalyptic interpretation of history, the re-integration of the psyche, and the renewal of intersubjective and intrasubjective relationships. As Möhring says, he has distilled his interpretation from critical readings too numerous to cite individually, among which Frye’s “brilliant” and “unrivalled” Fearful Symmetry figures prominently (186). The commentary explicates Blake’s mythos and the shifting relationships among his characters while incorporating historical, biblical, and Miltonic allusions and etymologies; there are briefer commentaries on the illuminations. Möhring displays a fine sensitivity to Blakean ambiguities and conflicting perspectives, and is endearingly honest about paradoxes for which he feels completely unable to suggest a solution. But the commentary, steeped in Blake’s own language, often reads like a prose version of the poem itself; uninitiated readers will probably find it challenging. The inclusion of “The Design of The Last Judgment,” as a reproduction followed by a first-time German translation of the text, is a fitting pendant to this presentation of Milton, with its orientation toward biblical and psychic apocalypse and its emphasis on Blake’s hybrid art.

Möhring’s translation of Milton is excellent, and goes a long way toward fulfilling his ambitious aim:

The translation itself tries to be a poetic one; that is, it attempts to take in everything I was able to see and to hear—levels of meaning, internal and external references and allusions, sentence structure, sound pattern, spelling, punctuation—and to convert it so that, in the end, there is once again a poem. (186)

Möhring’s painstaking work pays off in the sonorous lines of this German Milton, and the careful translations of Blake’s challenging vocabulary (e.g., “vegetative,” “generation”) that maintain internal allusions but also take account of particular contexts. Blake’s neologisms and constructed entities work particularly well in German, because of the language’s ability to build new compounds: one feels that Mondscheinraum was what Blake would have wanted to write for “moony Space” or Schlagaderpuls for “pulsation of the artery”; Weibmännlich und Mannweibliche illustrates hybridization and mutual influence more effectively than Blake’s own “Female-male & the Male-female.”

Although there is little overlap between the two translations under review here, the lyric “And did those feet in ancient time” and “The voice of the Devil” from The Marriage of Heaven and Hell are included in both volumes and allow for a direct comparison.

It indeed appear’d to Reason as if Desire was cast out; but the Devil’s account is, that the Messiah fell, & formed a heaven of what he stole from the Abyss. (Zwischen Feuer und Feuer 216)

Es erschien der Vernunft tatsächlich, als sei das Verlangen vertrieben worden; aber es ist des Teufels begin page 27 | ↑ back to top Verdienst, daß der Messias fiel & einen Himmel bildete aus dem, was er dem Abgrund stahl. (trans. Eichhorn, 217; my italics)

Der Vernunft kam es tatsächlich so vor, als wäre das Begehren verstoßen worden, doch der Teufel stellt es so dar, daß der Messias fiel und daraus was er dem Abgrund stahl einen Himmel baute. (trans. Möhring, 145; my italics)

Eichhorn’s Verlangen as a translation of “desire” may have been prompted by the sound patterns of the nearby Vernunft, vertrieben, and Verdienst; cognate with “longing,” Verlangen emphasizes need and nonfulfillment. Möhring’s Begehren, a less common word, awakens biblical and sexual resonsances and connotes a fiercer, more active desire that better suits Blake’s Devil. Eichhorn’s “es ist des Teufels Verdienst” seems a rare mistranslation, rendering “the Devil’s account” not as “the Devil’s version” but in the sense of “it is on account of the Devil that . . . .” Further down, Eichhorn’s translation of “in Milton, the Father is Destiny” as “in Milton ist der Vater die Vorsehung [providence]” gives the phrase a more positive inflection than it has in Blake, or in Möhring’s translation of “Destiny” as Schicksal.

On the whole, Möhring makes more extensive and imaginative use of the capabilities of the German language—compound words and neologisms, the subjunctive mood for indirect speech, more antiquated or formal vocabulary choices where these are more exact or contain appropriate allusions. These lend his translations more power. Eichhorn’s translations, geared toward accessibility, sometimes choose sound over exactitude of sense, yet still manage most of the time to preserve Blakean nuances. Given their distinctive aims and intended audiences, both are admirable. These publications should make Blake’s art available to new groups of readers, and continue the reception of Blake—apparently, now, a more-or-less integrated Blake for a more-or-less unified Germany—into a new millennium.