article

www.english.uga.edu/wblake

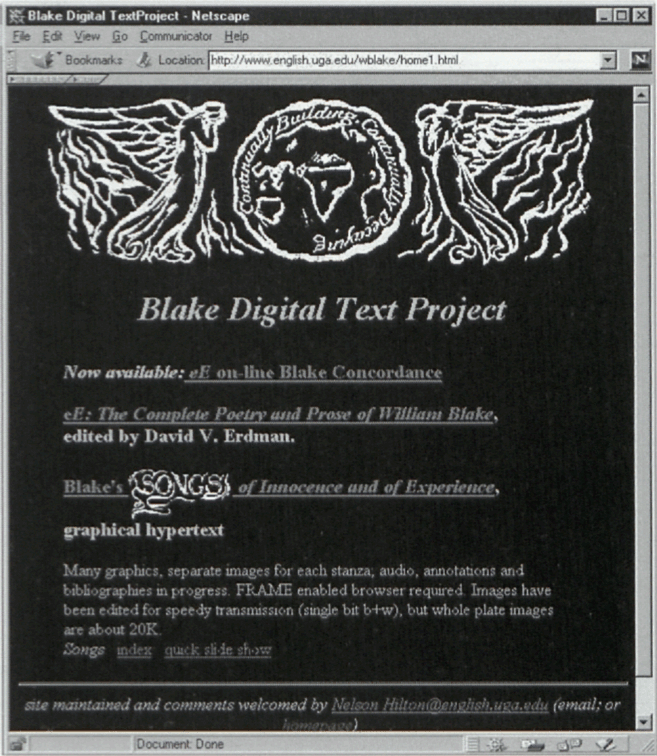

The “Blake Digital Text Project” (http://www.english.uga.edu/wblake) originated in 1994 with the desire to create an electronic, online, interactive, enhanced version of the long out-of-print 1967 Concordance to the Writings of William Blake, edited by David V. Erdman. A simultaneously growing acquaintance with hypertext led to reconsideration of Blake’s best-known work in that light and prompted the “Songs Hypertext.” Both of these exercises, then, arise from possibilities opened by the manipulation of text in digital form, and so prompt the project’s rubric, which denominates an effort unrelated to any attempt at an “archive.”

The enabling circumstance for the concordance comes in a letter of 14 March 1995, which conveys the permission of the copyright holders David V. Erdman and Virginia Erdman to use freely David Erdman’s edition of The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake (1982, rev. 1988). Such generosity is characteristic of the vital political and intellectual commitment of a life devoted to making Blake more accessible and permits a fitting conclusion for a work which originated in Erdman’s preparation of a text for the 1967 Concordance (though the difficulty of that task resulted in Keynes’s edition being used).

The initial text file was created by unbinding a copy of the Erdman edition and scanning the text with optical-character[e] begin page 12 | ↑ back to top

recognition software. The resulting file of just under 50,000 lines was as error prone as such output is wont to be and required several proofreadings to begin with. The file was then reorganized into a roughly chronological sequence so that any search output would follow in that order (also more or less the order of Erdman’s Concordance, if not his edition). As the file was to be processed using Perl, which in its simplest mode reads a file line by line, it was quickly evident that processing would be facilitated by each line’s having its own unique identifying information, so this was inserted in semi-automated fashion. In this file, then, one line appears like this:J83.73; E242| Weaving the Web of life for Jerusalem. the Web of life

In order to effect a reduction of the text file size and, consequently, processing time of about 20%, blank lines were then removed and replaced with “<P>” tags at the end of the line preceding the empty line.

The interesting case has recently been made that Unix is the operating system particularly congenial to literary folk and that the scripting language Perl is now one of its major attractions (Scoville); according to Larry Wall, its principal author, “Perl is above all a text processing language” (25). The heart of the initial Perl script employed to search the text file—the variable ($search) to search for having been assigned—looks as follows:

m/ (^ [^ \ |] +) \ | (.*) ($search) (.* (<p>$) ?)/or, to summarize:

(—1—) (-2-) (—3—) (-4—(-5—))

This goes through each line of the text file and applies a template of regular expressions, and in every line in which it finds (or rather, “matches,” “m/”) an instance of $search (“$” is Perl’s way of indicating a scalar variable, here named “search”) is able to report that line broken into components of (1) the characters before the “|” (the line identifier-like “J83. 73; E242”); (2) the characters (if any) before the $search; (3) $search itself (the value assigned to the variable); (4) the characters (if any) after $search, and finally (5) the tag “<P>” if present just at the end of the line (the second “$”, not to be confused with the first, is Perl’s way in this location of denoting the end of a line). These components can then be arranged for printing in various ways—in creating HTML output, for instance, $search could be wrapped with emphasis or color tags, or the identifier could be displayed in a smaller font or indented on a following line.

The electronic concordance thus offers several improvements over the computer-generated printed concordance of over 30 years ago, an age when “big iron” COMMUNICATED IN TELETYPE. Erdman’s Concordance prints only words, and not all of those, as it omits very high-frequency instances such as articles and pronouns. The electronic concordance distinguishes between upper and lower case letters and permits searches sensitive or insensitive to case—so it is possible to compare easily Blake’s more than 200 instances of “Eternity” with the 30-odd appearances of “eternity.” The computer is just as happy to search for single characters, like punctuation marks, or all instances of any character combination—“-ing,” for example—or combinations with “placeholders” (e.g., s.ng for “sing, sang, song, sung” [s.ng\. would capture only those instances where a period followed the “g”]).

Useful as such access may be, anyone familiar with more recent concordances will wish for the additional convenience of key-word-in-context (KWIC) format, not to mention the capability of Boolean searches. Processing the text file for KWIC output is more involved than merely identifying and printing lines which contain the search string. As the KWIC context can wrap from or around line breaks, these must be stripped from the file and the whole read into a single array. For processing the array, it has proved more feasible to separate the identifiers from the lines and associate them by identifying each with the appropriate unique line number. So, for instance, we in effect find in the array: “31000 Joy’d in the many weaving threads in bright Cathedrons Dome 31001 Weaving the Web of life for Jerusalem. the Web of life 31002 Down flowing into Entuthons Vales glistens with soft affections.<p>” With this arrangement we can return a specified number of characters begin page 13 | ↑ back to top

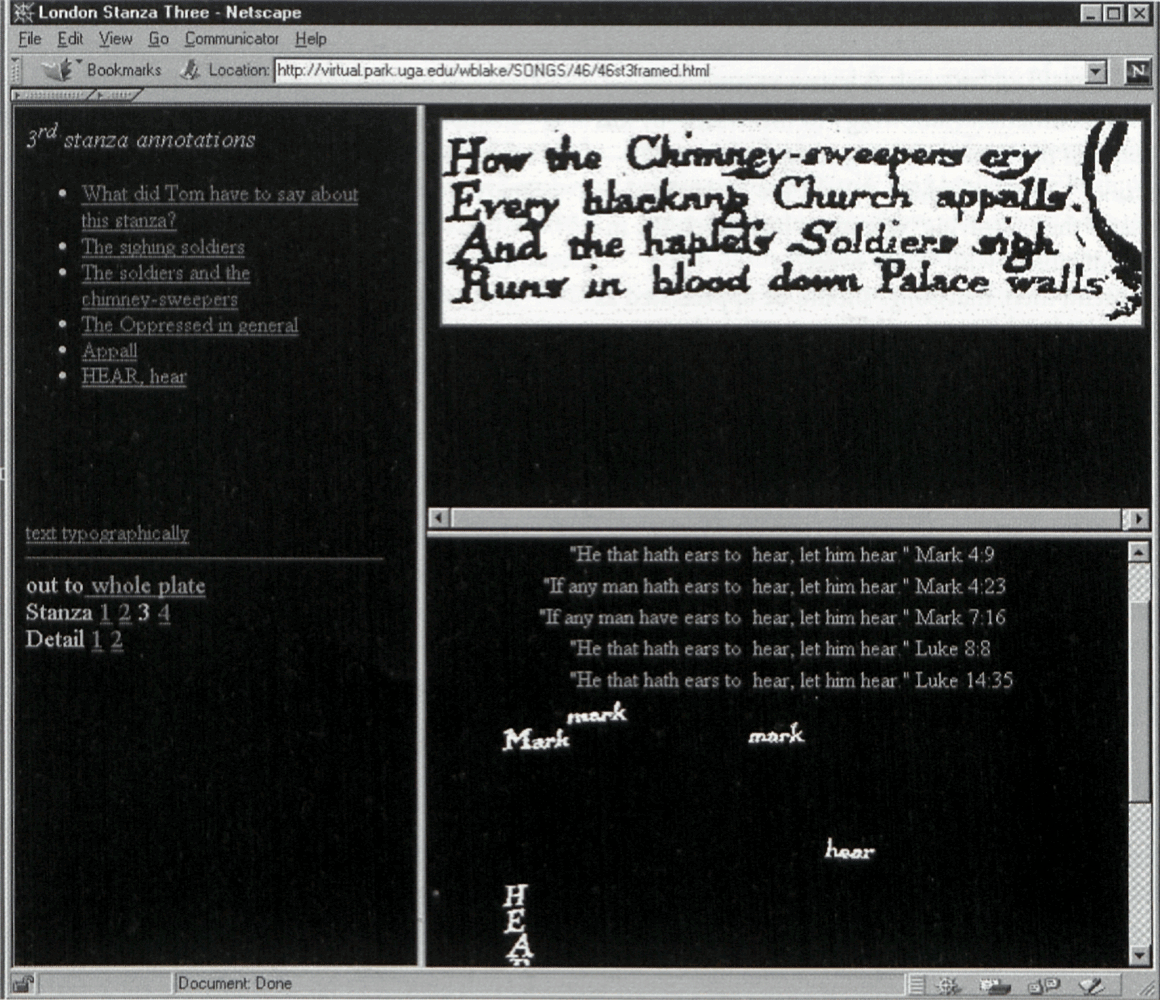

or words on either side of $search (rather than having to stop at a line ending or beginning), mark line endings by replacing any five-digit number with a virgule (/), and identify the line by the number and its occurrence[e] before or after the search term in conjunction with a separate array which tells us in effect that “31000 J83.72 31001 J83.73 31002 J83.74”. It is the job of a 300 mH Sun Ultra working millions of operations per second to effect all these things almost instantly, and thanks to the “common gateway interface” (CGI) protocols, access and input to and output from the concordance scripts running on that server are available over the web.It makes little difference for the computer whether the binary (“digital”) data which it processes are originally textual, graphic, aural, or video. What difference there is, more as issue today than in the foreseeable future, concerns time: large files can be processed less “almost instantaneously” than small ones, and in the digital realm a picture or sound (or their combination) “costs” considerably more bits than a word. The text of “The Lamb” in ASCII might run 800 bytes, while an 8-bit (256 colors) image of the plate might be 100 times that size and take correspondingly longer to process. Beginning with the axiom that Blake’s lettering is an important aspect of appreciation of his poetry, realizing that anything less than “almost instantaneous” is self-defeating in an electronic environment, and assuming that a simulacrum of shape and line are more important than color, the Project in 1995 began a digital “reading edition” of Songs of Innocence and of Experience. Photographs of an uncolored copy were digitized and reduced to a single-bit format (i.e., every pixel is either off or on—black or white) which could represent “The Lamb,” for instance, in an economical 14,000 bytes. As the full plate images are not exceedingly legible given the pixel size supported by existing monitor displays, enlargements of each stanza—usually less than 10,000 bytes in size—were also offered. These enlargements were occasionally edited pixel by pixel to enhance legibility (particularly with inked-over interior spaces in letters like e, d, A, etc.). The arrival of “frames” in HTML (Hyper Text Markup Language) saved the viewer from the “minesweeping” which would have begin page 14 | ↑ back to top

been required by the initial plan to offer annotations as invisible “hot-areas” on image-maps of the stanza enlargements—now the stanza sits in its own frame while another frame lists the available annotations which in turn are displayed in a third frame. HTML also opened the possibility of presenting Songs as hypertext.“By ‘hypertext,’” writes Ted Nelson, who invented the term over 30 years ago, “I mean nonsequential writing—text that branches and allows choice to the reader, best read at an interactive screen. As popularly conceived, this is a series of text chunks connected by links which offer the reader different pathways” (in Landow 3). Stuart Moulthrop must speak for many, however, in commenting that he’s “never really understood what Nelson meant when he called hypertext ‘non-sequential writing’” and then suggesting that “polysequential is a better way to describe hypertext” (Moulthrop). But whether one agrees with either of these definitions, or prefers instead to think of “text that is experienced as nonlinear, or, more properly, as multilinear or multisequential” (Landow 4), there seems little dispute that hypertext is “best read at an interactive screen.” From which it follows that such a reading best suits Blake’s Songs of Innocence and of Experience, given a re-cognition of that work as hypertext.

Certain it is—excepting those select readers very deep into Songs—that few have ever read Songs of Innocence in any linear sequence published by Blake. It could hardly be otherwise given that the editions and facsimiles by Keynes, Erdman, Bentley, and Lincoln treat Songs of Innocence (1789-1827) in terms of Songs of Innocence and of Experience (1794-1827), and treat that work itself in terms of its last seven instantiations. So the order of a work published some 50 times is determined by some 15% of its total. Even with regard to the entire Songs we find Blake in 1818 or later, some quarter-century after the first joint publication, specifying “[t]he Order in which Songs of Innocence & of Experience ought to be paged & placed” (E 772) as a sequence distinct from the received order. In fact, none of Blake’s separate editions of Songs of Innocence correspond with the usual sequence.

The different sequences of poems with their distinct juxtapositions can create very different readings. Before the advent of hypertext, appreciation of this intrinsic aspect of begin page 15 | ↑ back to top

Songs was hampered by the usual decision to follow the particular order mentioned above. To be sure, in The Illuminated Blake David Erdman offers en appendice the various orderings, referring to them by “number” of the normative pattern, and the information is accessible via G. E. Bentley, Jr.’s Blake Books, but these necessarily cryptic entries are too time-consuming for most readers to decode and apply.The Songs hypertext obviates this difficulty by making the various sequence-links from a particular poem readily visible and instantly accessible. Arrows in the upper corners of the frames on either side of a particular poem toggle a list of links to the poems which precede or follow according to their respective copies. Clicking on the arrow [>] in the upper right corner of “The Lamb” (www.english.uga.edu/wblake/SONGS/8) opens a list of all the different poems which follow on this in different copies. Copies of Songs of Innocence are identified using the lowercase letters a through u, copies of Songs of Innocence and of Experience are referenced in UPPERCASE A through AA, with the exception of the late, similarly sequenced copies (T2UWXYZAA) which are identified collectively as @. The specific information regarding these various copies to be found in G. E. Bentley, Jr.’s Blake Books and Blake Books Supplement is now, with the generous permission of Professor Bentley and Oxford University Press, to be incorporated into the hypertext.

In the case of “The Lamb,” one can see that while it is in fact followed most often by “The Little Black Boy” (in the conventionally accepted order), there are 15 other possibilities as well. In fact, in Songs of Innocence, it is followed more often by “The Blossom.” Clicking on the upper left arrow [<] to see the list of poems which precede “The Lamb” in various copies, we can note that “The Lamb” and “The Blossom” are joined together in nearly two-thirds of the copies of Songs of Innocence. One can then follow any of the respective links to that title, jumping from one copy’s sequence to another’s.

These considerations are not entirely pedantic. The “Introduction” to Innocence lays out a concern with individual and cultural progression from unarticulated sound to words to writing which builds on the “scene of instruction” depicted on the preceding title page. The poem which most begin page 16 | ↑ back to top often follows the “Introduction,” “The Shepherd,” might also be thought of as part of the front matter or introductory sequence once it is seen to work as a new Milton’s Lycidas-like veiled condemnation (following “To the Muses” by less than six years) of the “lean and flashy songs” of the 1780s—the saccherine “sweet lot” which delight the sheep herd of the public and their “straying” attendant but which the inspired guide dismisses with “How sweet”!

The argument, then, that Songs should be appreciated as depicting a series of stages or vignettes in the coming-to-consciousness of language/the symbolic order/art (etc.) (see www.english.uga.edu/wblake/SONGS/begin) becomes more credible with the realization that “Infant Joy,” a logical starting place for such considerations after the introductory plates, does in fact occupy that slot (fifth in SI, sixth in SIE) as often (11 times) as it does its usual position, third from the end of Innocence as plate 25. The point is not to argue that one sequence is better than another-but as a pedagogical tool an idealized progression might be useful.

The digital medium of the hypertext also makes possible the incorporation of audio into our experience of Songs, a capability appropriate for the work of an artist who composed his own melodies and whose work has frequently been set to music. From a pedagogical point of view, the musical interpretations are valuable for the ease with which they make obvious almost instantly the reality of different yet convincing interpretations. The musical interpretations also illustrate dramatically that reading itself is as much a matter of effective performance as the determination of some final truth. The presence of audio for a given poem is signaled by the image of the piper in the upper right; clicking here opens a list of versions available as streaming audio which can play while other links for that text are explored. The small “i-icons” open information concerning the source of the material (much of which has generously been made freely available by the artists Greg Brown, Finn Coran, and Gregory Forbes). The growing collection of audio interpretations seems promising both for use in comparisons to open the way to interpretation of a poem and as a prompt to new individual or group engagement with the text.

The principal use of the “Blake Digital Text Project” in my own classes thus far has been the creation and development of the Songs hypertext. Over the past three years, students in three small graduate classes have focused some of their energies on the preparation of bibliographies and annotations. This specialized use can now be expanded by providing a means to accept additional annotations from any scholar or class who may have something to add—moving finally, perhaps, toward a sort of commentary variorum. Contributions are identified by the creator’s initials which are in turn appropriately linked to the master list of names and contacts for all who have worked on the project.

Works Cited

George P. Landow. Hypertext 2.0: The Convergence of Contemporary Critical Theory and Technology. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins, University Press, 1997.

Stuart Moulthrop. “The Shadow of an Informand.” http://raven.ubalt.edu/staff/moulthrop/hypertexts/hoptext/Non_Sequitur96299. html

Thomas Scoville. “The Elements of Style, UNIX as Literature.” http://ww.performancecomputing.com/features/9809of1.shtml

Larry Wall, Tom Christiansen, and Randal L. Schwartz. Programming Perl. 2nd ed. Sebastopol[e]: O’Reilly, 1996.

![Concordance to The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake—Dept of English, Univ of Georgia

- Netscape http://virtual.park.uga.edu/Blake_Concordance/ Beta2 version for KWIC format—still a little buggy

(15.iv.99), but a faster server! Word, phrase, letters: web <==Search eE 1. grave dug for a child, with

spiders webs wove, and with slime / Of anci FR40; E287 2. / The bird a nest, the spider a web, man friendship.

/ The selfi MHH8; E36 3. epings all the day: To spin a web of age around him. grey and hoary! d VDA7.19; E5-

4. w’d behind him / Like a spiders web, moist, cold, & dim / Drawing o BU25.10; E82 5. ities in sorrow.

/ 7. Till a Web dark & cold, throughout all / T BU25.15; E82 6. rrows of Urizens soul / And the Web is a

Female in embrio BU25.18; E82 7. t208> / None could break the Web, no wings of fire. / 8. So t BU 25.19;

E82 8. pe! / And each ran out from his Web; / From his ancient woven Den; SongLOS6.4; E68 9. / They cry O

Spider spread thy web! Enlarge thy bones & fill’d / W FZ1-15.3; E309 10. The Spider sits in his labourd

Web, eager watching for the Fly / P FZ1-18.4; E310 11. d & takes away the Spider / His Web is left all

desolate, that his littl FZ1-18.6; E310 12. rkness & whereever he traveld a dire Web / Followd behind him

as the FZ6-73.31; E350 13. he / Follows behind him as the Web of a Spider dusky & cold / Shiv FZ6-73.32;

E350 14. wing from his Soul / And the Web of Urizen stre[t]ched direful shivrin FZ6-73.35; E350 15. Ran thro

the abysses rending the web torment on torment / Thus Ur FZ6-74.8; E351 16. a mile / Retiring into his dire

Web scattering fleecy snows / As he FZ6-75.26; E352 17. As he ascended howling loud the Web vibrated strong /

From heaven t FZ6-75.27; E352 18. uadrons of Urthona. weaving the dire Web / In their progressions & prepa

FZ6-75.33; E352 FZ6-73.34; E350 A living Mantle adjoind to his life & growing from his Soul FZ6-73.35;

E350 And the Web of Urizen stre[t]chd direful shivring in clouds FZ6-73.36; E350 And uttering such woes such

bursts such thunderings <t751>](img/illustrations/blake-digital-text-project-concordance.033.01.bqscan.png)

![The Angel - Netscape http://virtual.park.uga.edu/wblake/SONGS/41/41frall.html Greg Brown Finn

Coren The Angel I Dreamt a Dream! what can it mean? And that I was a maiden Queen: Guarded by an Angel mild:

Witless woe, was neer beguil’d! And I wept both night and day And he wip’d my tears away And I wept both

day and night And hid from him my hearts delight So he took his wings and fled: Then the morn blush’d rosy

red: I dried my tears & armd my fears, With ten thousand shields and spears. Soon my Angel came again: I

was arm’d, he came in vain: For the time of youth was fled And grey hairs were on my head THE Chimney

Sweeper A The SICK ROSE CILMV NURSES Song DJ The Little Vagabond E A POISON TREE FQ LONDON K [three flowers] N

HOLY THURSDAY (SE) O The GARDEN of LOVE P The Tyger RT@ INFANT SORROW S index](img/illustrations/blake-digital-text-project-angel.033.01.bqscan.png)