ARTICLE

On First Encountering Blake’s Good Samaritans

The Vision of Christ that thou dost see

Is my Vision’s Greatest Enemy . . .

Thine is the Friend of All Mankind,

Mine speaks in parables to the Blind . . .

Thy Heaven doors are my Hell Gates.

“The Everlasting Gospel” e

lines 1-2, 5-6, 8 N 34, E 524

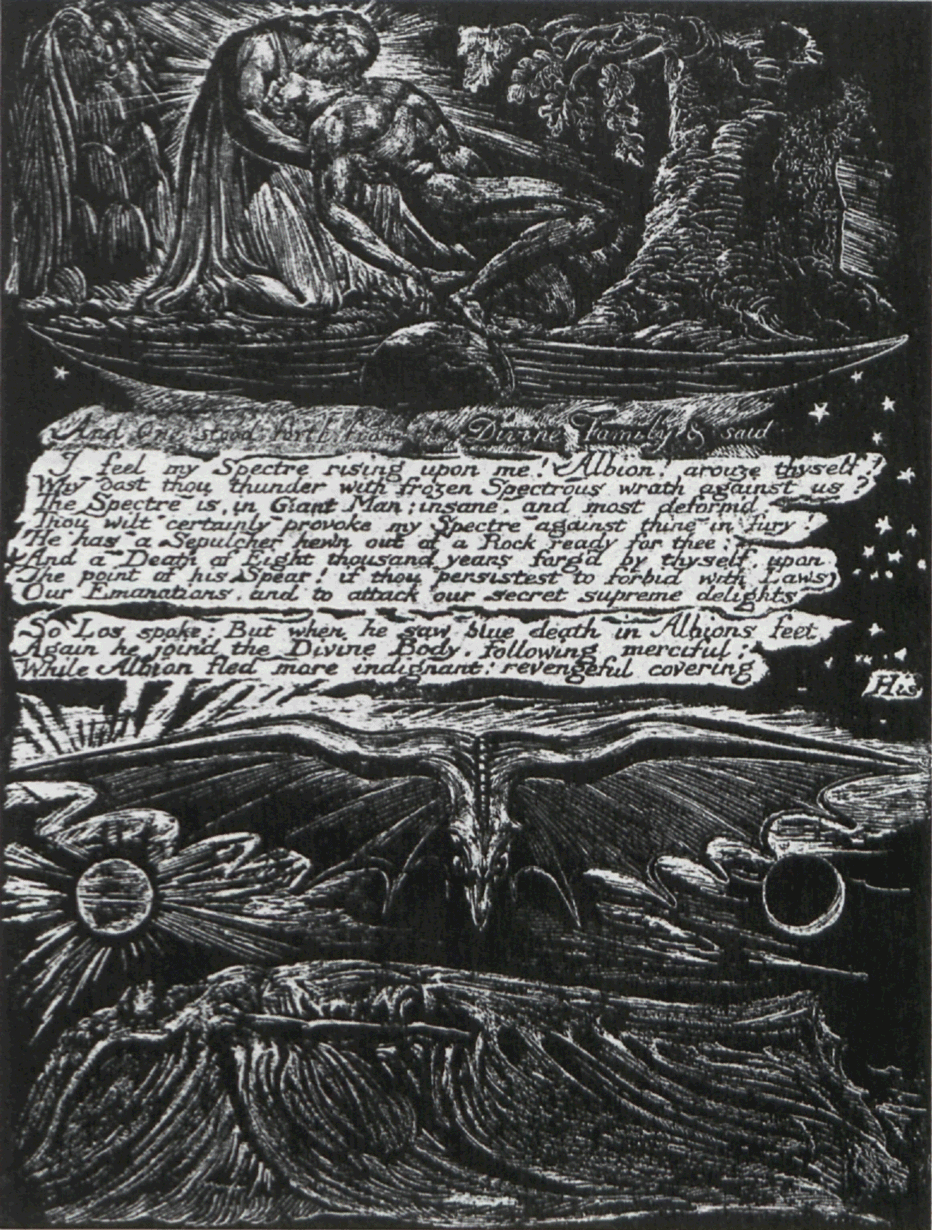

Blake’s sixty-eighth watercolor design for Edward Young’s The Complaint: or, Night-Thoughts on Life, Death & Immortality, which occurs in “Night the Second: Time, Death, Friendship,” is an unusual representation of Jesus’s well-known parable that was spoken in response to a certain lawyer’s series of tricky questions beginning: “What shall I do to inherit eternal life?” (Luke 10:25-37). Of Blake’s two earlier treatments of this subject, the sketch on page 84 of his Notebook was prepared for possible inclusion in The Gates of Paradise: the Man Who Had Fallen Among Thieves lies face down and is being passed by on the other side by two who ought to have tried to rescue him; the identities of these characters is problematic, but it is certain that no Good Samaritan has yet appeared. Blake’s other “Good Samaritan” picture was actually published, as an interlinear design to the right of the third and fourth “Proverbs of Hell” on plate 10 of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. Here a personage entering is distressed to discover a naked victim stretched out on the ground and rushes to help while the spread-armed perpetrator is getting away. This scene is also susceptible to interpretation as a variation on the Cain and Abel story, to which Blake often refers and, on the titlepage of The Ghost of Abel, plate 1, included a similar figure of a flying spreadarmed villain in an Expulsion scene and also as a spreadarmed Cain beneath the description of the theatrical “Scene.” Further consideration of the issues in the Good Samaritan designs is continued in the first footnote.1↤ 1 The Notebook of William Blake: A Photographic and Typographic Facsimile, ed. David V. Erdman, with the assistance of Donald K. Moore. rev. ed. (New York: Readex, 1977) 84: i.e., N 84. The editor conjectured that they are either “Good Samaritans or highwaymen.” There could not, on the contrary, be even one Good Samaritan in this pair of passers-by, who make no attempt at benefaction. For The Marriage of Heaven and Hell plate 10 (as well as reproductions and other works of illuminated printing): The Illuminated Blake, annotated by David V. Erdman (Garden City, NY: Anchor Press/Doubleday, 1974) 107. For The Ghost of Abel, plate 1, Illuminated Blake 381. Another relevant spread-armed figure appears in MHH 14, Illuminated Blake 111. There is no sign that this figure bears any special relationship to the story of Cain. To minimize the burdensome documentation I shall make few references to the generally excellent new Blake Trust/Princeton UP edition of the illuminated books. In footnote 22 I shall be more specific about matters in Morton D. Paley’s 1991 volume, Jerusalem.The best inference (pace Erdman) is that the pair of men passing by the flattened victim, in the night scene of N 84, represent the Priest and a highwayman derived from the good Samaritan parable. These are the considerations: one of this pair of passers-by in this night scene wears a robe, the other a sword. It is not that Good Samaritans don’t carry swords. Around Bassano, in the sixteenth century, they seem regularly to have done so. Usually they also had a servant or dogs as part of their equipage. Bad Samaritans (who are in the majority everywhere), we may infer, did the same. Good Samaritans sometimes also wore robes which, to our eyes, makes it hard to distinguish them from Priests. But Good Samaritans, however equipped, never pass by on the other side. It is a premise of the parable that not as much can be said for Priests and Levites, for they were exempted by the Law from performing such deeds of Charity if the victim seemed already dead; see esp. Num. 19:11-22. The passer-by with the sword might indeed be construed as the Levite, but in other representations he never carries a sword or wears action clothing, or is even a fellow traveller of the Priest. Therefore to make a Blakean inference, the unlikely pair, the Priest and the Highwayman, have become fellow-travellers and passers-by, and are bound for the Gates of Hell, a destination not “For Children.” The text for “A Vision of the Last Judgment,” which in N 84 was written on all sides of the Good Samaritan sketch for Gates, can hardly be appreciated in Erdman or in any other printed text, save in the facing transcription. Why did Blake (a book-designer) strive so hard to contain these ideas on this page that he contrived to set them forth in the form of a marginal frame of words—and yet had to conclude with words carried over to the next page, N 85? Those who would equate this design-strategy with Blake’s usually expedient strategy of simply getting his thoughts down on available paper in the Notebook are missing something. Here I must point out that the motto Blake slipped in, on either side at the middle of the Good Samaritan picture, is a proverb of vision and a subtitle for the section on ideas, rather than an exposition of the picture: “A Last Judgment is neces[picture]sary because Fools Flourish.” Blake did publish what I take to be a quite different pictorial variation on the Good Samaritan as an interlinear design following the sixth line of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, plate 10. The central figure, who lies on her left side, is the victim of the spread-armed villain with an indistinct companion, who is making a getaway, at the left. At the right a figure rushes in, waving his arms in distress, ready to act as the benefactor. Whether because of the connection between this villain and those on the first page of The Ghost of Abel, this should be thought an allusion to the Good Samaritan story is, however, debatable. This is one of many cruxes to be encountered in this iconographic study where the vagaries of caricature and cartooning must be acknowledged. Blake the artist was free to transform or invert pictorial motifs and thus challenge the viewer to grasp a new point. “And so Dear Christian Friends[,] how do you do?” (E 507). Before making a final judgment as to the two encounters on the road, in N 84 and MHH 10, one should ask: How would the Devil who, in the latter, is revealed in the colophon picture as engaged in the spurious teaching-work of deconstructing the scroll of holy writ, at the conclusion of the “Proverbs of Hell,” expound these concise pictures? With Proverb of Hell 67? Go thou and do otherwise.

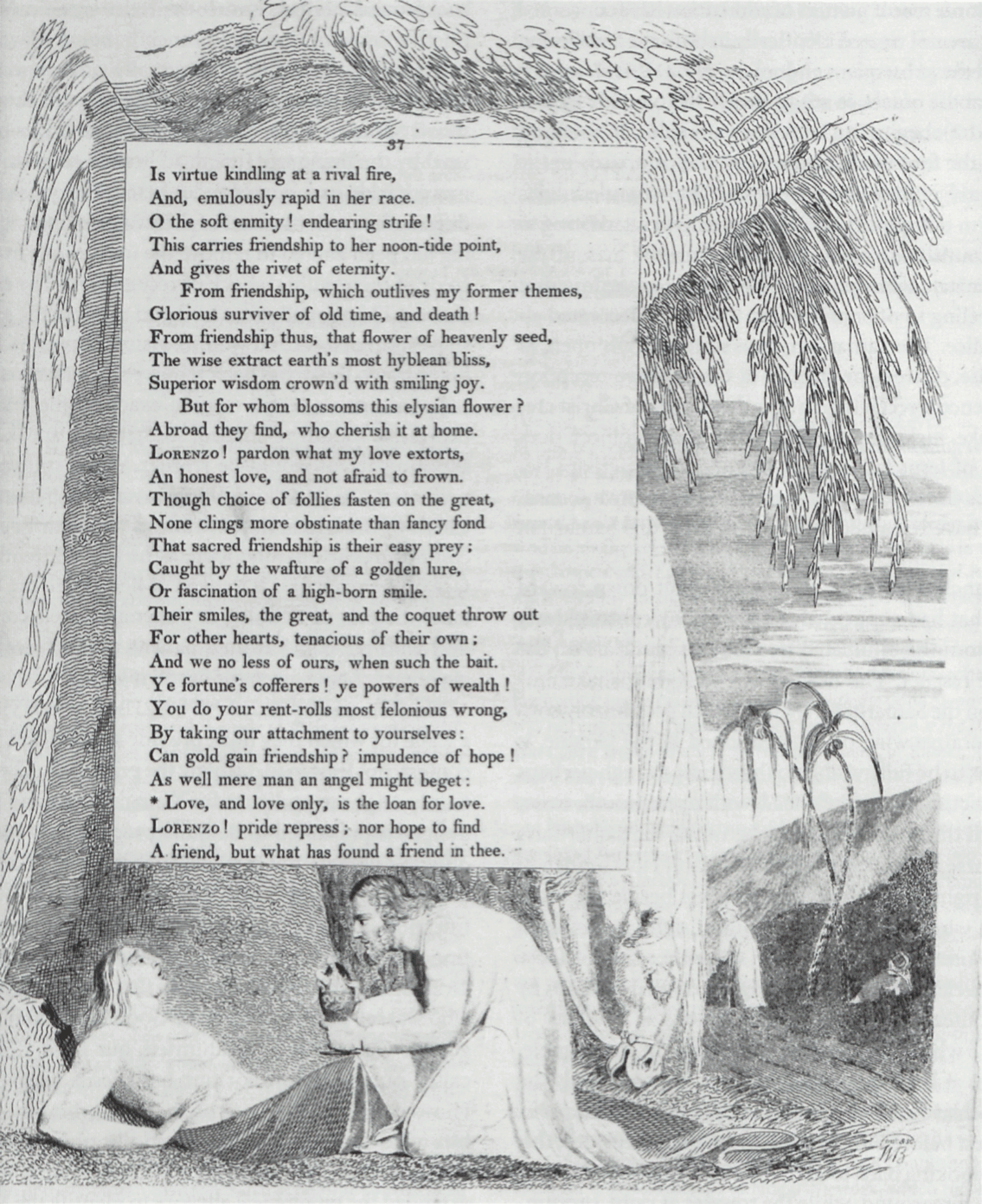

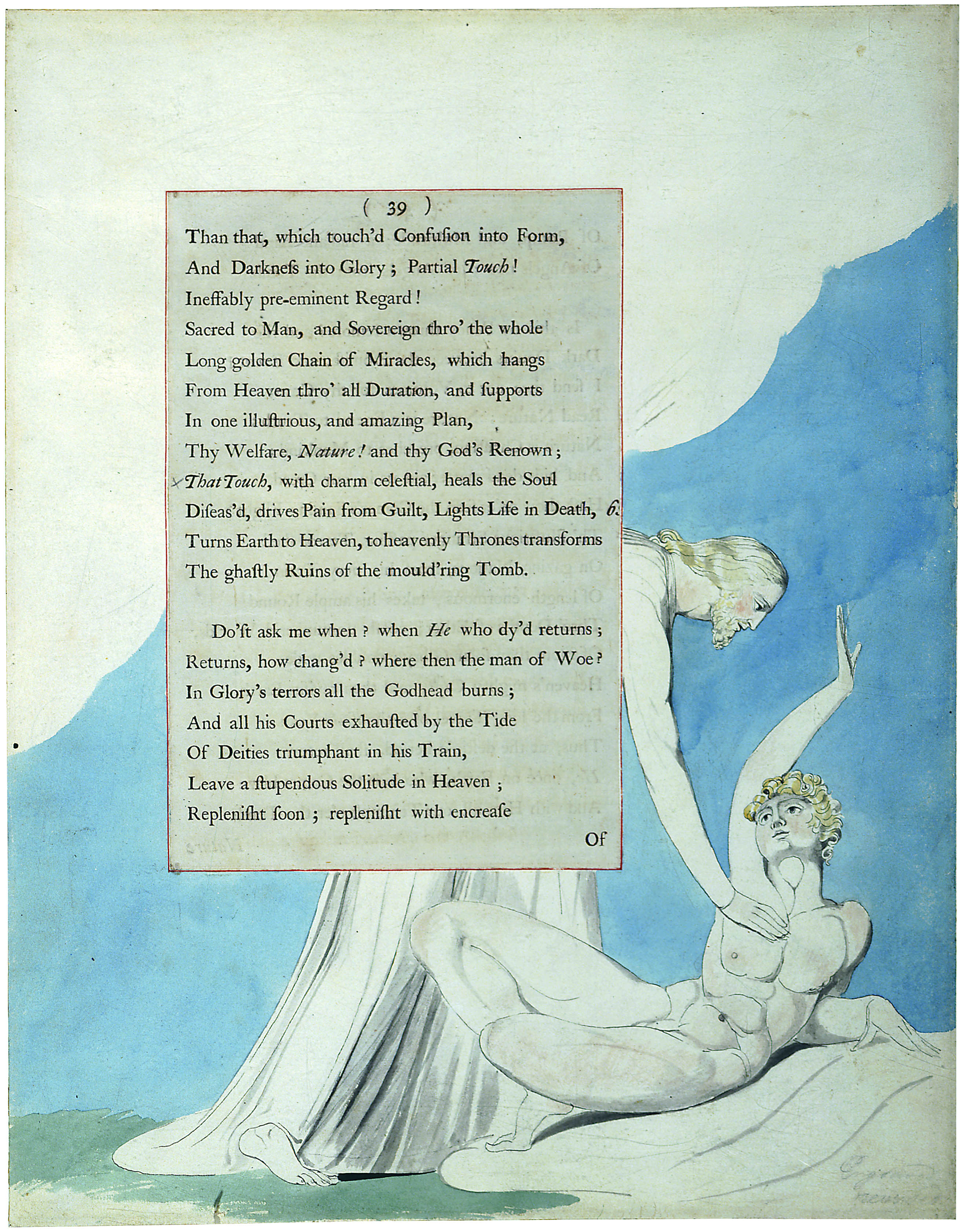

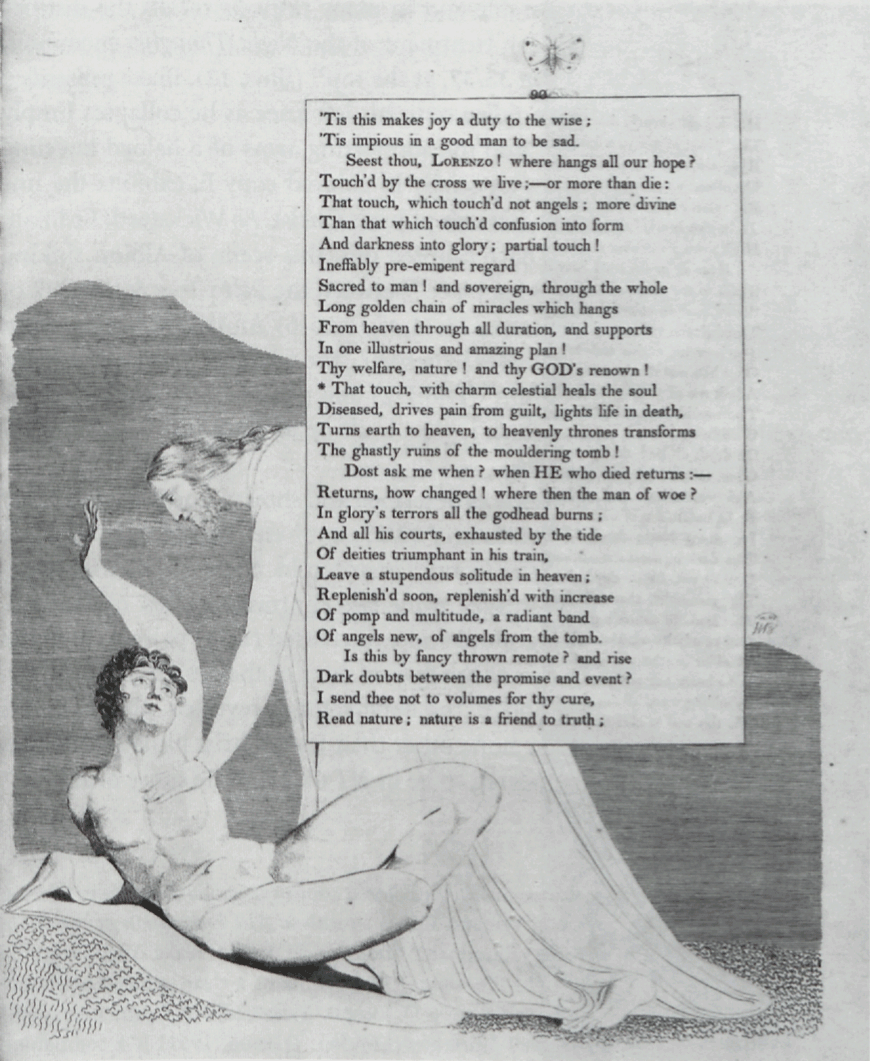

begin page 69 | ↑ back to topIn Night Thoughts 68:21E (illus. 2) Blake represents the Samaritan as Jesus himself, kneeling in the act of offering the fully conscious wounded victim a serpent-decorated vessel—an ellipsoid lidded chalice or drinking goblet rather than a medicinal bottle or flask—in an emotionally charged moment of eye-to-eye engagement that occurs just before the traditional scene in which the Samaritan treats the victim’s wounds with oil and wine. This unsettling juxta-position of familiar and unexpected images, against a back-drop of two large trees, living and dead, is further complicated by the design’s (at best) oblique relationship to the line of Young’s poem marked for illustration on this page: “Love, and Love only, is the Loan for Love” (II, 571).2↤ 2 Though the 1797 edition bears the extensive title: The Complaint, and the Consolation; or, Night Thoughts, this claims more than Young had promised his serially-published four “Nights” would deliver: “The Consolation” is Young’s later (1745) title for the long terminal “Night the Ninth.” But perhaps by employing “The Christian Triumph” as the sole title for the fourth and last unit, with no indication of other Nights to follow, and embellished with Blake’s 43 illustrations and an “Explanation of the Engravings” publisher R. Edwards indicated that his 95-plus pages represented an essential Young’s Night Thoughts.Except for the unreliable color films of all the subjects that were issued by EP Microform in the 1980s, the only generally good quality reproductions of (practically) all the subjects are to be seen in what I shall refer to in this essay as the Clarendon edition: i.e., William Blake’s Designs for Edward Young’s Night Thoughts: A Complete Edition, eds. John E. Grant, Edward J. Rose, Michael J. Tolley, with co-ordinating editor David V. Erdman (Oxford: Clarendon, 1980) 2 vols. Blake’s 538 watercolors and drawings, which were made recto/verso on the borders of 16 × 12-inch paper with Young’s text set in, are reproduced on large paper and numbered consecutively. Seventy-eight of the watercolors, including the Good Samaritan picture, NT 68, are reproduced in color, with captions, on unnumbered pages toward the end of Volume II. Following are much-reduced color reproductions of two different copies of the titlepages (only) for the four Nights in the 1797 edition, engraved by Blake and perhaps also colored by the Blakes. Only one colored copy of Blake’s set of 43 prints, that in the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, has been (in 1988) reproduced in its entirety. Almost certainly, however, Blake had no responsibility for its coloring. Peculiarities in the coloration of the Good Samaritan print, NT 43E, indeed are among the strongest evidence that the not-unskillful colorist did not understand Blake’s design. See Martin Butlin and Ted Gott, William Blake in the Collection of the National Gallery of Victoria, Robert Raynor Publications in Prints and Drawings, Number 3 (Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 1989) 157-78 and pls. 51:i-xliii. In his study of this copy in the 1989 issue of Art Bulletin of Victoria no. 30, 24-25, Michael J. Tolley saw no reason to question Blake’s responsibility for the coloring, as I do here. The Clarendon edition also includes a section of engraving proofs for the 1797 edition, among them the proof for the Good Samaritan subject, which was utilized for page 129 in Night the Ninth of the manuscript poem, Vala, or The Four Zoas—though (unlike some other proofs) this print is not significantly different from the published state. The second volume concludes with a reproduction of an entire uncolored copy of the 1797 edition of Night Thoughts, including the (anonymous) two-page “Explanation of the Engravings,” which is bound into most copies. The (reduced) reproduction of the proof page used as p. 129 for Vala and the accompanying commentary are both presented in high-quality facsimile by Cettina Tramontano Magno and David V. Erdman, The Four Zoas by William Blake: A Photographic Facsimile of the Manuscript with Commentary on the Illuminations (Lewisburg: Bucknell UP, 1987) 243; 94-95. The 1963 Clarendon Press edition of Vala or the Four Zoas, ed. G. E. Bentley, Jr., presents actual size reproductions of the pages and thus gives a better sense of the scale on which Blake chose to address ideal viewers of his own epic-in-progress. Blake’s designs for Night Thoughts are summarized in catalogue form but only three of the watercolor designs—NT 117, NT 196, and NT 510, and some related drawings—are reproduced in Martin Butlin, The Paintings and Drawings of William Blake (New Haven and London: Yale UP, 1981) 1: 178-255. I have chosen not to employ Butlin’s catalogue prefatory number 330 (-334) because the abbreviation NT seems more self-explanatory when moving among the Night Thoughts designs, which often need to be distinguished from Blake’s other designs. To Butlin’s citation of the relevant literature on NT 68, the Good Samaritan picture, should be added Margoliouth’s important comments, which are discussed below. Other pictorial works by Blake are identified by Butlin’s catalogue and plate numbers, abbreviated as “cat.” and “pl.” The reviews of the Clarendon edition were discussed and debated in Blake 18.3 (1984-85) by myself and three reviewers: J.E. Grant, 155-81; W.J.T. Mitchell, 181-83; Morton D. Paley, 183-84; D. W. Dörrbecker, 185-90. The discussions were accompanied by good reproductions of these Night Thoughts designs (in illustrative sequence): NT 2 (misidentified as NT 1); NT 1E (proof, Harvard); NT 6; NT 8; NT 20; NT 78; NT 79; NT 264;[e] NT 345 (often referred to herein); NT 417. All quotations, including my epigraph, cite (as is customary) Blake’s texts as they appear in The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake, ed. David V. Erdman, with commentary by Harold Bloom; newly rev. ed. (Berkeley and Los Angeles: U of California P, 1982, 1988); cited as E followed by page number: E 524.

The most challenging feature of Blake’s portrayal of the Good Samaritan’s appearance in NT 68 lies in the characterization of the principals: why is the Samaritan represented as Christ, proffering a serpent-decorated vessel, and why is the half-dead victim straining to rise, his mouth open in a gasp or a shout, his right hand bent back at the wrist, palm toward the would-be benefactor with fingers raised in what appears to be a defensive gesture? The most extensive interpreters of this watercolor (illus. 1) and its closely related engraving (illus. 2) have put forward radically different accounts of what is going on.3↤ 3 Among the many features of the Introduction to Volume I of the 1980 Clarendon edition is a chronological “Checklist of Studies and Reproductions” (72-84) published through 1977. Those of special interest to this study are Margoliouth’s revised reprint of his 1954 essay (no. 34), “Blake’s Drawings for Young’s Night Thoughts,” in The Divine Vision: Studies in the Poetry and Art of William Blake, ed. Vivian de Sola Pinto (London: Victor Gollancz, 1957) 191-204, and (no. 83) Robert Essick and Jenijoy La Belle, eds., Night Thoughts or, The Complaint and the Consolation: Illustrated by William Blake, Text by Edward Young (New York: Dover, 1975), a reduced good-quality reproduction of the 1797 edition together with an introduction and a page-by-page commentary. Important discussions of NT 68:21E published since the 1980 Clarendon edition include John E. Grant, “Jesus and the Powers that Be in Blake’s Designs for Young’s Night Thoughts,” in Blake and His Bibles, ed. David V. Erdman (West Cornwall, CT: Locust Hill Press, 1990), esp. 77-79, and Christopher Heppner, “The Good (in Spite of What You May Have Heard) Samaritan,” Blake 25 (1991): 64-69, revised and condensed in chapter 6 of Heppner’s Reading Blake’s Designs (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1995), esp. 161-70. Unluckily neither Heppner nor I refers to Margoliouth’s essay; in consequence, he debates some matters with me that I had taken over from Margoliouth, without citation, as though they were commonly understood and accepted, not requiring documentation. H. M. Margoliouth (1954, begin page 70 | ↑ back to top

Because some recent matters of contention have concerned details that are not treated identically in both the watercolor, NT 68, and the subsequent engraving, NT 21E, it should be clarifying, at the outset, to study closely the two side by side (illus. 1 and 2), beginning with the watercolor. In the foreground, at the foot of two huge trees, the principals in the encounter are represented in profile. The wounded, half-naked victim of highwaymen is agitated and attempting to rise, his mouth wide open. He looks into the eyes of the Good Samaritan, who appears to the viewer in the image of Christ, kneeling to offer and uncap a serpent-decorated ellipsoid chalice. The Samaritan-Jesus’s mouth falls open, as if in surprise, distress, or chagrin at the negative reception his beneficence is receiving. In no other image of Christ created by Blake, including the engraving of this subject, does the mouth of Jesus fall open in this way. Also perhaps because Blake’s Christ seldom elsewhere kneels to anyone, commentators have refrained from identifying this Samaritan as Jesus.

Dead branches from the tree at left point down toward the stone that had supported the victim; by contrast, leafy branches from the bifurcated tree at right luxuriate on the side of the rescuer. The head-down wriggling snake embossed upon the Samaritan’s chalice, which presumably contains the curative wine or oil mentioned in the parable, is turned so as to be fully visible to the viewer though perhaps not to the victim; the snake’s head, with open mouth, twists back toward the donor. In the background, the Samaritan’s outsized horse is tethered to an (improbably) low branch of the tree at right, and is browsing on grass beside the road. Farther on, where the road drops out of sight, two crossed palm trees rise from the declivity. On either side of these trees are travelers who are departing downward, perhaps by different routes, to Jericho, already famous as “the city of palm trees,” which is mentioned by name in the parable. The traveler at left, with a walking stick, is presumably the Levite who had “looked on” the wounded man before he, like the Priest before him, “passed by on the other side”; this man is still looking back toward the encounter that is taking place in the foreground, while the traveler at right, presumably the Priest, pays no attention as he hastens downward. The Levite’s view, now that the Samaritan has arrived, we may infer, is probably blocked by the huge grazing horse. Whether or not the Priest and the Levite may rejoin the same invisible curving road, they do not go as fellow-travelers down to Jericho.

Blake altered this design in a number of particulars when he made the engraving, 21E, for page 37 of the 1797 edition of Night Thoughts (illus. 2), correcting, for example, the impossibly long legs of the victim in the watercolor version by covering the area of the protruding right foot with an extended roll of cloth. Other altered details, such as the more oak-like rendering of the bark of the tree at the right and the addition of varied fruits to the crossed palm trees in the background, perhaps have interpretive significance; the distinctive detail of the dead branch hanging down from the background tree at left is essentially unchanged from the watercolor to the engraving, though now, not clustered with shorter dead branches, but mingled with leaves perhaps issued by the living tree, the dead branch tends to stand out more starkly as a sign of a dead tree. The most significant differences are in the faces of the two principals: the engraving has been altered to remove the indications in the watercolor of their mutual shock of recognition. The Man Fallen Among Thieves still raises his hand to reject the gift, but the suggestion of a second wound, visible above his fingers, on his redrawn torso, has been removed. His face has also been redrawn, with a larger nose in exact profile and with the expressive mouth re-shaped, so that he is speaking to, not shouting at, his would-be rescuer. While still resisting, he now seems to be talking things over. The Samaritan Jesus Christ of the engraving encounters the victim-refuser with composure, lips hardly open, as he looks intently into the face of the man who is in need of help. Here the Samaritan takes the part of a healer, or a therapist, well-composed to deal with resistance from a patient who refuses the medicine that is being given for his own good.

The dramatic tableau of NT 68: 21E confronts viewers with a scene for which they must provide a significant part of the context, not least in identifying the principals. The predominantly Anglican audience for Young’s poem and for Blake’s designs is presumed to be quite prepared to recognize not only the parable but a traditional image of Christ in this unexpected context. There is ample foundation for this identification in biblical exegesis: in the fifth century St. Augustine and St. Ambrose, building upon an older exposition of Origen, had developed the idea that it was Christ himself who was, or was figured as, the Good Samaritan. As St. Augustine wrote, “even God himself, our Lord, desired to be called our neighbor. For our Lord Jesus Christ points to Himself under the figure of the man who brought aid to him who was lying half dead on the road, wounded and abandoned by the robbers.”4↤ 4 On Christian Doctrine, trans. J. F. Shaw, in The Works of Aurelius Augustine, ed. Marcus Dods, 9 vols., 3rd ed. (Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1883) 1: 33. See also Origen, Homilies on Luke, Fragments on Luke, trans. Joseph T. Lienhard[e] (Washington: Catholic U. of America, c. 1992), esp. Homily 6, 23-27 and Homily 34, 137-41. Post-Augustinian interpreters extended the typological allegory to identify the Man Fallen Among Thieves as Adam and the thieves as Satan, etc. It follows that the Priest and Levite, as Jews, represent the Old Law, the wine employed in the cure is the Eucharist, and the inn to which the victim is taken to recuperate is the Church. The main allegorical points of this interpretation of the parable are wholly in accord with the “spiritual” exposition of the story as quoted at length by Thomas Coke, and, as Heppner points out, with the interpretation of Matthew begin page 73 | ↑ back to top Henry, two leading evangelical commentators whose works were read in the late eighteenth century.5↤ 5 See Matthew Henry’s Commentary on the Whole Bible (c. 1707) (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1991) 5: 552-55. See also Stephen L. Wailes, Medieval Allegories of Jesus’ Parables (Berkeley: U of California P, 1987) 209-14. For a perspicacious modern account of the parable, see the concluding section of Andrew J. McKenna, Violence and Difference: Girard, Derrida, and Deconstruction (Urbana and Chicago: U of Illinois P, 1992) 211-21: “The Law Before the Good Samaritan.” McKenna liberates the parable from construal as an exhortation to do good deeds by emphasizing the predicament of the lawyer and Jesus’s other hearers as they are made to acknowledge that a non-Jew of an abhorred kindred race has shown himself the superior of high-ranking Jews in keeping the law.

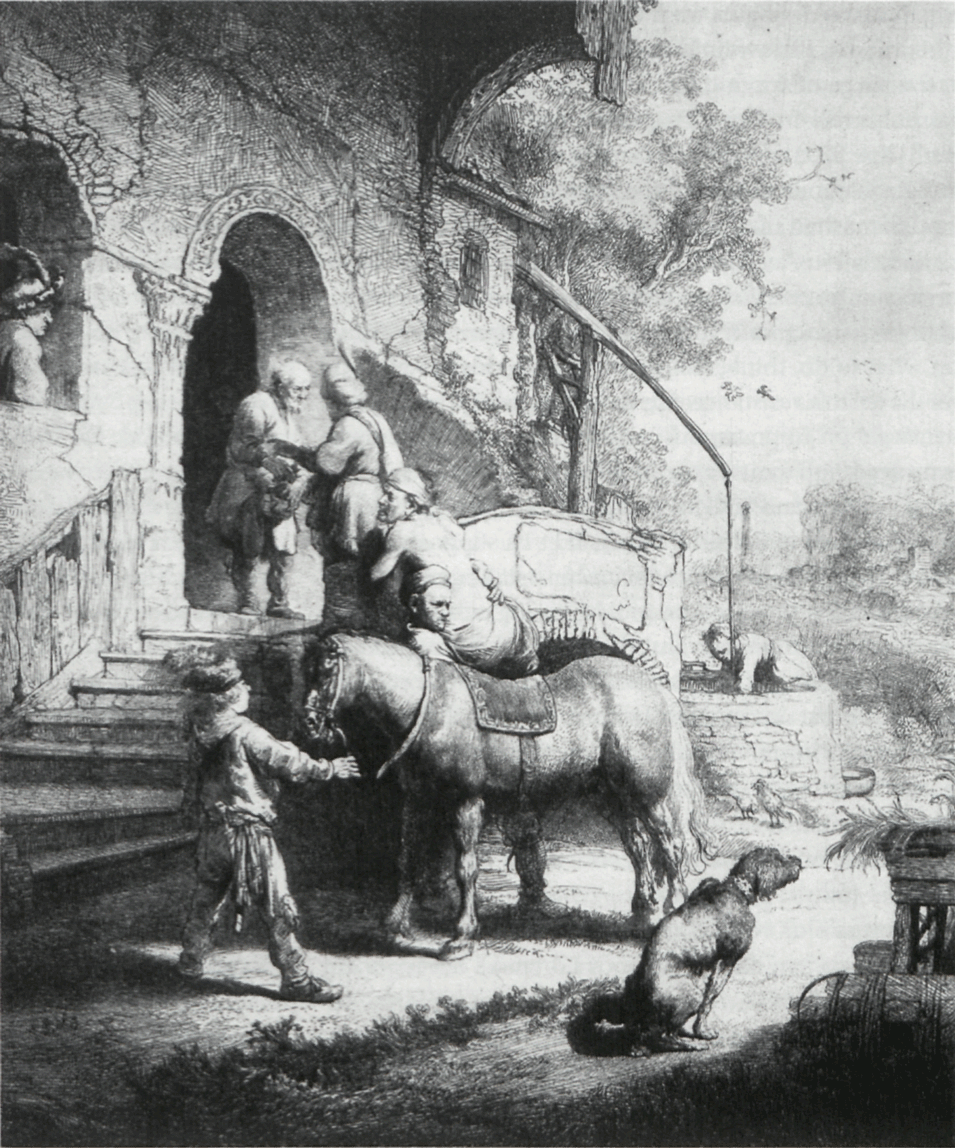

But in the visual arts, from the Reformation on, this representation of the parable disappears: Blake was probably the first artist since Heemskerck in 1565 to depict the Good Samaritan as Jesus Christ.6↤ 6 Though I am aware of no full catalogue of Good Samaritan pictures, Christopher Wright’s The World’s Master Paintings: From the Early Renaissance to the Present Day (London: Routledge, 1992) lists 43 European paintings on this theme, with a guide to their locations worldwide (see 2: 4, Index of Titles). But in his tally of eighteenth-century Good Samaritans Wright neglects to list Hogarth’s famous wall painting on the staircase of St. Bartholomew’s Hospital and does list several pictures by artists nearly anonymous. Wright, since he begins after the Medieval period, mentions only a few of the 18 pictures listed by Louis Réau, Iconographie De L’Art Chrétien, Tome Second: Iconographie De La Bible II Nouveau Testament[e] (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1957) 331-33. Réau also lists a number of Good Samaritans in illuminated manuscripts, including two in France which I have not seen, that feature Christ in the role of the rescuer. So far as the study of Blake is concerned, what matters most are representations of the Good Samaritan by British artists, or by other artists whose works were readily accessible to a Londoner of Blake’s time, or by artists (particularly those Blake felt strongly about) whose works were readily available in prints. Among those of particular interest are the engraving after Marten de Vos by Johannes Sadeler (the First, c. 1550-1600), one of four master engravers named in Blake’s “Public Address” (E 574), which provides good examples of the common elements that had become conventional in pictorial representations of the scene: the Samaritan in a turban or other Middle Eastern headdress, the victim unconscious or nearly so, the horse, the road, the departing Priest and Levite, and the city in the distance. Serial engravings (e.g., two sets by Heemskerck, one by Aldegrever) commonly feature three or more of the following episodes: the robbery, the passing of the Priest and Levite, the Samaritan’s medical intervention, the loading of the victim onto the beast, the journey to the inn, the arrival at the inn, the Good Samaritan’s negotiation with the innkeeper, either on arrival or at his departure the next day. Heemskerck, whose work Blake placed at the same level as that of Michelangelo, Raphael, Dürer, and Julio Romano (G. E. Bentley, Jr., Blake Records [Oxford: Clarendon, 1969] 422, 433, 448) produced two four-print sets on the Good Samaritan theme: the 1549 series depicts the robbers leaving the traveler half dead, the Priest and the Levite passing by while the Samaritan tends the traveler, the Samaritan carrying the victim to the inn, and the Samaritan paying the innkeeper in advance. The 1565 series presents almost the same episodes, but all are treated allegorically: the robbers are Cupido, Voluptas, and Error (Desire, Lust, and Error); the Priest and the Levite, as Aaron and Moses, represent Jewish ceremony and law; the healing is performed not by a Samaritan traveler but directly at the allegorical level, as by Christ on the cross raining blood on the victim’s wounds; finally, the risen Christ (carrying his cross) pays not the innkeeper but St. Peter, who holds the keys to the Church, and the payment is in the form of the Gospels and Epistles, reproduced in The Illustrated Bartsch, and more usefully in Ilja M. Veldman, comp. and Ter Luijten, eds., The New Hollstein: Dutch & Flemish Etchings, Engravings and Woodcuts / 1459-1700 / Maarten van Heemskerck, Part I (Roosendaal, the Netherlands: Koninklijke van Poll, 1993) 134-36. Heemskerck also made a fascinating major painting, Landscape with the Good Samaritan, which was not engraved. Thomas Kerrich in A Catalogue of the Prints Which Have Been Engraved after Martin Heemskerck, or Rather, An Essay Towards Such a Catalogue (London, J. Rodwell, 1829) does not usually specify where prints are located but offers clear descriptions of them. Probably the most distinguished Italian Renaissance paintings of the Good Samaritan in England in Blake’s time are two versions of the subject by Jacopo da Ponte, Il Bassano, one at Hampton Court since 1630, the other in Joshua Reynolds’s collection since 1772, now in the National Gallery, repr. as figs. 83-86 in Eduardo Arslan, I Bassano (Milan: Ceschina, 1960). But for an English audience in Blake’s time, the picture that comes closest to providing a universally recognized interpretive standard is Hogarth’s huge mural, The Good Samaritan (repr. except for left quarter in Mary Webster, Hogarth [1978; London: Studio Vista / Danbury, CT: Master Works, 1984] 71-73, 78), a companion to his The Pool of Bethesda, both of which were painted for the grand staircase of St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, not far from St. Paul’s, and easily accessible to Blake not only in the original but in the 1772 print by Ravenet and Delatre (illus. 8), published in Boydell’s splendid 1790 assemblage of Hogarth’s work, which included Blake’s own print of The Beggar’s Opera. For the Bassano brothers see also Erica Pan, ed. Jacopo Bassano l’ incisione (Bassano del Grappa: Museo Civico, 1992). The posthumous print, no. 60 Buon Samaritano, is attributed to “I Bassan, p.” i.e., Jacopo dal Ponte as designer (not his brother or son Francesco, as the catalogue declares) and signed by Boel as engraver. The tree beside the head of the victim is bifurcated; the trunk closer to the head of the victim was cut off; the other rises and flourishes. Also no. 120, Buon Samaritano, an eighteenth-century print of another Jacopo Bassano painting which belonged to Reynolds and is now in the National Gallery, London, catalogued as no. 277; it features the loading of the victim, after treatment, upon the Samaritan’s beast. Two seventeenth-century pictures that variously treat problems of recognition in the Good Samaritan story are a painting by Luca Giordano, in which the Samaritan looks villainous but acts charitably to the unconscious victim, and a print by Rembrandt, dated 1633 (illus. 9); these will be discussed below. Unlike Heemskerck, however, who designed a print that switches the figuration to the exegetes’ allegorical level of interpretation to depict the act of healing as a shower of blood raining down on the victim from Christ upon the cross, Blake depicts Jesus in the guise of an ordinary wayfarer, doubtless viewed by the victim to be a Samaritan, offering aid by the roadside, according with the literal level of the parable. The extreme rarity of the Jesus-Samaritan identification in Protestant art, particularly among pictures that were made in the eighteenth century or that were then prominent in England—most notably, those of Hogarth (illus. 8) and Jacopo Bassano—leads to the inference that Blake had a particular point to make begin page 74 | ↑ back to top by returning to this medieval and Renaissance symbolism. Although it is odd that the author of the 1797 “Explanation of the Engravings,” who readily identifies the other obvious images of “Christ” or “the Saviour” in NT 1:31E, NT 121:34E, NT 143:38E, and NT 148:40E, is silent on this point, it is safe to assume that Blake expected his viewers to recognize what the victim himself does not, could not, know: the Samaritan who has come to his aid is the Messiah.

Heppner is right to emphasize the importance of the dramatic framework of the story in Luke 10:25ff., which presents the parable as Jesus’s adroit response to a sharp lawyer’s trick question on a vexed point in the Torah. Jesus, recognizing that this “questioner who sits so sly” has no sincere concern for eternal life, about which he had pretended to inquire, responds to the legalistic interrogation with a supra-legal test-case that requires the ostensive scholar of Jewish law, presuming to piety, to judge as if he were the victim whether the heterodox Samaritan were a more faithful observer of the law than either the Priest or the Levite—or at least of that part of the law that commands a person to love his neighbor as himself.7↤ 7 This law was spoken by the Lord to Moses in Leviticus 19:18; curiously, Matthew Henry did not mention this cross-reference, though he understood the sense well enough. Similarly, Henry deplored the “cruelty” of the Priest and the Levite in passing by “on the other side” on their way between Jerusalem and Jericho, rather than exercising the “charity” that the “half-dead” victim required. Henry did not attempt to explain the insensitivity of these clerics, though other commentators had done so, and Blake may well have been aware both of the relevant biblical text and of Renaissance prints that show the parts of the passers-by taken by Moses and Aaron. In Numbers 19 the Lord told these two of the curious process of purification that is to be followed in cleansing from sin. Then, 19:11-22, the Lord explains at length the pollution that occurs when anyone has contact with any dead person, including, it goes without saying, one who dies in the faith of Moses and Aaron. Since the waylaid victim had been left “half-dead,” it was hardly surprising that the Priest and the Levite would not risk ritual pollution by ministering to him. At a safe distance they could hardly tell his exact condition, and what would be the consequences for their clerical obligations even if he were still alive when sighted but then died while in their care? Prudence would dictate that they have somewhere to get to and accede to their duties. Once the questioner has submitted the answer required by the parable, Jesus abruptly switches the perspective from the victim to the rescuer, and instructs the devotee of Jewish law to adopt the despised Samaritan as a model, and extend neighborly love even to strangers and enemies: “Go and do thou likewise.”

Reviewing most of the relevant biblical texts about the Jews’ contempt for the Samaritans, Heppner goes some distance toward recovering the force of Jesus’s representation of a hated Samaritan as the beneficent “neighbor” of a Jew. One additional episode involving Samaritans—not cited by Heppner—bears on the case: in Jesus’s encounter with the Woman at the Well, his request for water is such a shocking violation of social taboo that the woman responds suspiciously, “How is it that thou, being a Jew, asketh drink of

me, which am a woman of Samaria, for the Jews have no dealings with the Samaritans” (John 4:9). The cultural tensions built into the parable are heightened and further complicated by Blake’s pictorial identification of the Samaritan as Christ. Ethnically, of course, Jesus of Nazareth was not a Samaritan, but because of his unorthodox behavior he was inferentially identified as one by some of his suspicious compatriots: “‘Say we not well that thou art a Samaritan, and hast a devil?’ Jesus answered, ‘I have not a devil; but I honor my Father, and ye do dishonor me’” (John 8:48-49). In this exchange, as the early commentators noted, Jesus denies only that he has a devil, not that he is a “Samaritan.” This silence in the text is meaningful; if it caught Blake’s attention, it may well have offered scriptural reinforcement for his use of the symbolic Christ/Good Samaritan identification in the Augustinian exegetical tradition engaged in his reworking of the parable.Given that this Good Samaritan is enacted by Jesus Christ, what should an eighteenth-century Christian audience make of the serpent-marked chalice in which he proffers oil or wine, and why would the victim resist being helped?

The snake-decorated lidded cup—more properly, a ciborium—is Blake’s most striking departure from iconographic convention. Artists other than Blake usually depict the Samaritan’s vessel as a flask, not a chalice, and no other artist marks it with a serpent. There are no snakes, decorative or otherwise, in Sadeler’s Good Samaritan print, for example, or in other depictions of the parable by painters or begin page 75 | ↑ back to top graphic artists such as Veronese, the Bassani, Heemskerck, Pencz, Aldegrever, van de Velde, met de Bles, Fetti, Merian, Rembrandt and his followers, Ribera, Teniers the Younger, Bourdon, Luca Giordano, or, in the English school, Hogarth, Hayman, Highmore and West; or in emblem books from Ripa to Hertel; or in a sculpture done by Flaxman in 1813-15. It is noteworthy that none of the later nineteenth-century artists who address the Good Samaritan theme: Delacroix, Van Gogh, Watts, et al., treated it at all as Blake had done in 1797.

Despite Heppner’s numerous examples of the positive attributes of snakes in Greek mythology and the ingenuity of his argument for Aesculapius as a pagan type of Christ, the primary association of serpent, in a Christian context, is with evil, not healing; the Harper’s Bible Dictionary (1985) provides a convenient summary of support for this self-evident point. Even if it were supposed that the victim is knowledgeable enough to identify the snake as an emblem of the Greek cult of Aesculapius, as maintained by Heppner, the grounds for refusal would remain the same.8↤ 8. An able art-historical account of Aesculapius not mentioned by Heppner is J[an] Schoten, The Rod and the Serpent of Askelepios (Amsterdam, London, New York: Elsevier, 1967). See esp. chapters 6 and 9 for some remarkable Christian permutations of the symbols associated with the Greek god. Lemprière (1788) on “Aesculapius” and James Hall, Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art, rev. ed. (New York: Harper & Row, 1979), mention little that could be employed to render this Blake serpent redemptive. Whether the proffered cure be understood as Samaritan, or Aesculapian, or Gentile-exotic (something from Ancient Britain, say), or proto-Christian, the alien potion or ointment would be perceived as an abhorrence by an observant Jew.

It makes no difference to my argument whether the snake were depicted as a mere decorative motif or as a live reptile in the act of striking: Christian tradition, following Jewish tradition, encodes nearly all manifestations of the serpentine form in Christian art as evil. The chief Gospel exception is Jesus’s appropriation of the curative emblem of Moses’s brazen serpent as the antitype and prophecy of his own crucifixion (John 3:14, as noted by Heppner). Disentangling this notion in relation to the watercolor entitled Moses Erecting the Brazen Serpent, based on Num. 21: 6-9 (Butlin, cat. 447, pl. 521) is a challenge. But even in the night meeting with “the rich learned Pharisee” (E 518), Nicodemus (which is like the dialogue with the lawyer in that it concludes with promise of “eternal life”), the evil nature of serpent qua serpent is assumed; that is why the miraculous brazen serpent is needed as an antidote. Apart from this one reference to Moses’s miracle and the injunction to be “wise as serpents, and harmless as doves” (Matthew 10:16), whenever Jesus himself uses imagery of snakes—whether denouncing his contemporaries as a “generation of vipers” (e.g., Luke 3:7), asking his hearers whether they would give a serpent to a child who had asked for a fish (Luke 11:12), or promising the faithful that they, too, will have power over serpents (Luke 10:17-19)—the negative import of this usage is clear. Since apostolic times (e.g., Romans 16:20), it has been understood that Christ, as the Second Adam, fulfills in his crucifixion the prophecy of Genesis 3:15 by crushing the serpent’s head. This is shown in the penultimate or final designs in the three Paradise Lost series (Butlin, cat. 529.11, pl. 642; cat. 536.11, pl. 655; cat. 537.3, pl. 659). These scenes forecast Jerusalem 76, to be discussed later, in which, however, the serpent does not figure. I believe the preponderance of iconographical and biblical evidence, supported by the Genesis-to-Revelation identification of the serpent with Satan in exegetical tradition, weighs overwhelmingly against Heppner’s positive interpretation of the snake, in Blake’s Good Samaritan scene, as an emblem of Aesculapius.

There is a troublesome Young text early in Night the Second, which occurs on NT 41, p. 8, unrelated to that Blake design, and on p. 20 of the 1797 published edition, which lacks any design, that declares that Aesculapius does not figure in the friendly kind of concern engaged by Young’s poem:

For what calls thy Disease Lorenzo?! not

For Esculapian, but for Moral Aid.

(II, 50-51)

Heppner (1995, 169) attempts to enlist these lines for his Aesculapian theory about NT 21E:68, but their plain sense works directly against the interpretive line he wishes to maintain for the picture occurring 17 or 27 pages further into Night the Second. Moreover, Young’s exhortations in NT:21E, p. 37, lines 556 and especially 572, which directly follows the asterisked line

*Love and love only, is the loan for love,are again addressed to “Lorenzo.” It follows that, in Blake’s tableau, Lorenzo corresponds to the Man Fallen Among Thieves, who is refusing the proffered cure, while Young the advice-giver who wishes to provide Moral Aid, is playing Christ. Aesculapius could be of no help here.

The more specific configuration of serpent-and-cup, as noted by Essick and LaBelle, refers in Christian iconography to a central episode in the legend of St. John the Evangelist (or the Divine). As a test of faith by the Emperor Domitian, the saint was made to drink from a poisoned cup that had killed two other men or, in another version of the story, the compelling authority is the high priest of Diana of Ephesus. John, the only apostle to meet the ordeals of martyrdom without losing his life, proves immune to the drink, and the poison, in the form of a serpent, slithers harmlessly away.9↤ 9 In Jacobus de Voragine, The Golden Legend, trans. Granger Ryan and Helmut Ripperger (New York: Arno, 1969), re 27 December 61-62, the story of the test of St. John by poison is told without employment of the serpent, but there are countless representations of St. John holding a cup containing a serpent, both as a solitary saint and among assemblages of saints, as, for example, in Memling’s 1479 The Mystic Marriage of St. Catherine. This legend of St. John is clearly told in Hall, Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art.

begin page 76 | ↑ back to topIt is also notable that Blake departs from convention in representing the Samaritan’s proffered container of liquid as a lidded goblet, thus signifying that this is a drinking vessel rather than the oil vial or wine flagon that would be indicated at the literal level of the story. Other artists portrayed the Samaritan equipped with a narrow-necked vessel, clearly a portable medicine bottle, from which he pours oil or wine directly into the (usually unconscious) victim’s wounds, or applies the balm or antiseptic with his hands. By contrast, Blake’s covered vessel, held up directly in the conscious victim’s line of sight, more forcibly and obviously recalls the exegetical tradition that identifies the Samaritan’s cure with the taking of communion: the ciborium is the receptacle that holds the consecrated wafers of the Eucharist. Offered as a drinking vessel, this representation of the sacrament might seem to take Luther’s side in the Chalice Controversy, which supported the Protestant practice of making the cup as well as the Host available to laymen—though Blake, an unchurched dissenter who was baptized, married, and buried by Anglican clergy, was unlikely to have been concerned with such disputes of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation. The point is that the Samaritan’s presentation of this peculiar vessel, at eye level, indicates that the cure it contains is to be taken by mouth. And as the Samaritan is only just about to open the vessel—its contents are not yet being poured out, as in most representations of this episode by other artists—the conscious victim is able to exercise a right of first refusal to the ministrations of his rescuer.

Too exclusive attention to the drama of the encounter between the men represented in NT 68:21 E may obscure deeper issues that ought to be considered along with the Good Samaritan parable: How should Charity and Faith be related to good deeds? Blake wrote this memorandum in his Notebook: “Jesus . . . makes a Wide Distinction between the Sheep & the Goats[;] consequently he is Not Charitable” (N 72, E 695).

Later he inserted this aphorism, a virtual title, on either side of his sketch for the very Good Samaritan problem that was finally excluded from The Gates of Paradise: “A Last Judgment is Neces [“Emblem 54”] sary because Fools flourish” (N 84, E 561).

Why, it should be questioned, if Jesus was “Not Charitable” did he play the Good Samaritan? And what is to become of “Fools” at the “Last Judgment”? Two answers Blake would have thought to be profoundly anti-Christian are raised in Counter-Reformation art that Blake would have been aware of through prints containing similar themes if not through the particular paintings I shall mention. In two recent exhibition catalogues, several pictures are featured that show Christ either as exterminator or as a cosmic reservoir

The other Counter-Reformation motif, the Fountain of Blood, is hardly less appalling. As “The Fountain of Elijah” or “Fons Pietatis” Jesus stands on one side in heaven, Mary on the other; he spurts blood, she milk, into a fountain atop which Elijah stands holding a fiery sword and around which the Church Fathers trample upon their adversaries while Carmelite Nuns express their devotions. There were also pictures that focus on Jesus: Christ in a Chalice (no. 57), in which he stands, ready to be drunk, or Allegory of the Eucharist (no. 55), in which Christ grows a grape vine from the wound in his chest and squeezes out the juice of a cluster onto an ecclesiastical platter held out by a pope. All this occurs while Christ is backed by the cross and kneels upon the world that swims in a pool of blood and is watched adoringly by an

assembly of seven shorn sheep. Closer in symbolism to our point of departure in NT 68:21E, however, is the later sixteenth century Man of Sorrows (Allegory of Redemption) by Passerotti (no. 52), in which Jesus, holding his cross, stands on a shore and looks up at the Father while making the sign of the span of mortality with his right hand; Blake was to employ the same sign in Night the Second, NT 44:13E, and elsewhere. But most remarkable in Passerotti’s picture is that the stream of blood issuing from the wound of Christ falls into an overflowing chalice where it is being fed upon both by a dove and by a serpent, which is wound four times around the stem of this vessel of charity. These animals are derived from the aforementioned Matthew 10:16.Since the blood that spills out of this cup also functions to convey the writing upon the scroll that is wrapped about the base of this chalice, believers are supposed to understand that Christian doctrine derives from the overflow of blood. Lest we surmise that such indulgences had become quite out-of-date among English Protestants, consider Cowper’s Olney Hymn, Bk. I, 79 of 1779: “Praise for the Fountain Opened.” Those who still indulge in the hymn books imagine that they should bathe in Christ’s blood (rather, indeed, than drink it), but this exercise of faith is hardly distinguishable for those who think about it. If The Man who had Fallen Among Thieves, in NT 68:21E, had been informed as to the full extent of the symbolism represented by the snake-decorated ciborium being proffered for his health, he would doubtless have persisted in his rejection of whatever it was that the ostensible Samaritan had put in it. Blake would have agreed that such observances have no place in the Everlasting Gospel: If cannibalism were Christianity. . . .

The choice of the anticipatory moment is an unusual feature of Blake’s NT 68:21E, whether or not it necessarily leads to inferences as to the Christian mythology it would involve. Other artists who had projected images from the parable, whether in single subjects, or representations of numerous episodes within one picture, or renditions of the parable in a succession of four pictures, concentrate on earlier or later begin page 78 | ↑ back to top text-based episodes, mainly the assault of the thieves, the passing by of the Priest and the Levite, the Samaritan dressing the victim’s wounds, the loading of the mended victim onto the Samaritan’s equine mount and the journey to the inn, and the arrangements with the innkeeper for his further care. When the victim is dazed or unconscious, he can play at best a passive role. But Blake in effect places the viewer in the psychological situation of an alert and wary victim, whose first impression of a serpent-marked chalice is that it would denote evil and corruption, not healing—even if the bearer of the cup were Jesus and Aesculapius rolled into one. If this primary symbolic identification of the serpent with evil in Christian art were set aside or diminished, the whole force of Blake’s reinterpretation of the Good Samaritan parable in the Night Thoughts designs would be lost.

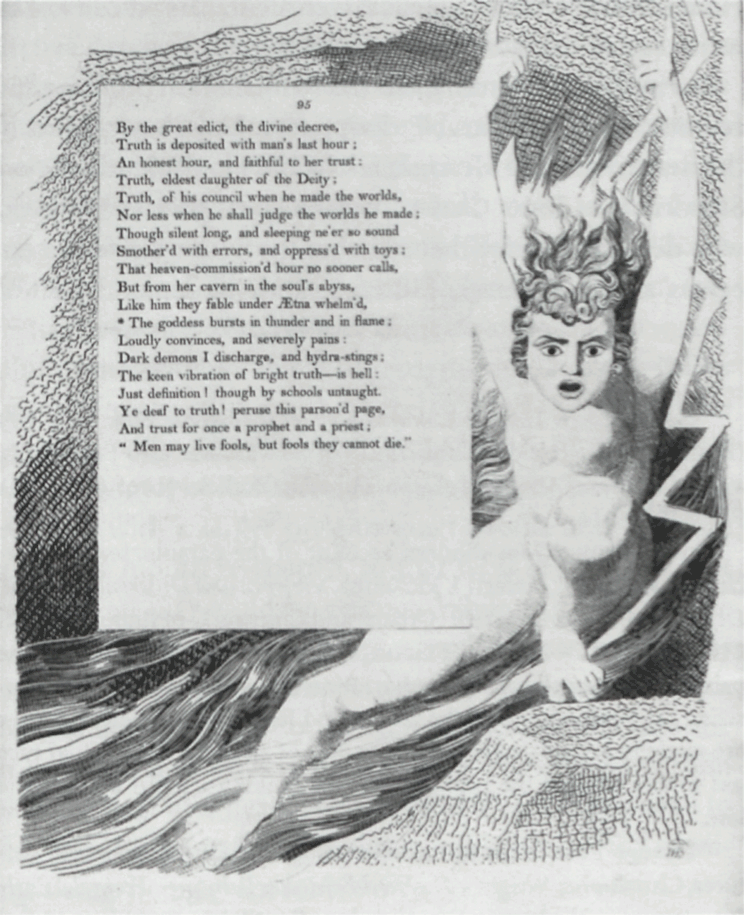

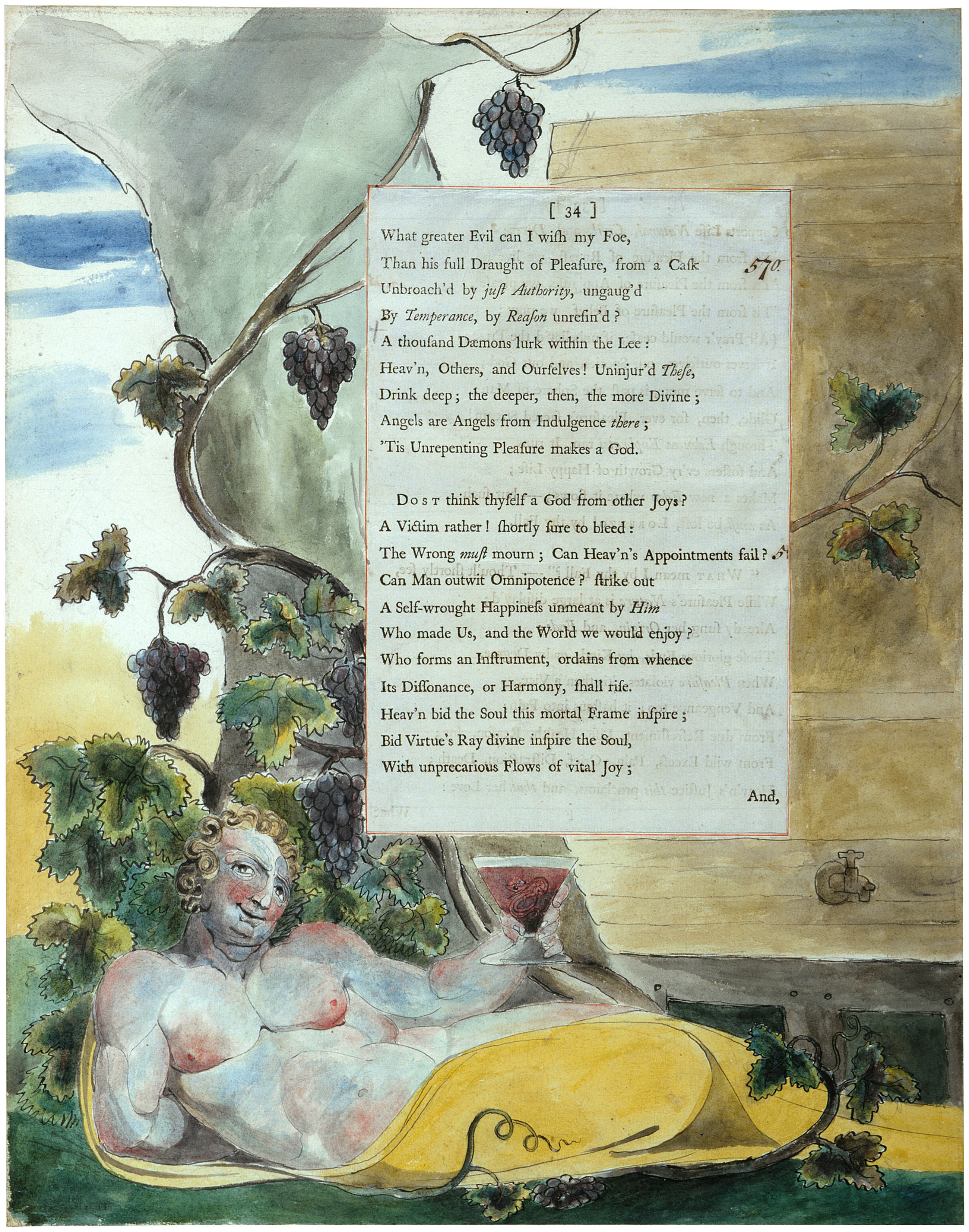

What is the evidence, considering serpents and cups in the Night Thoughts designs themselves, for maintaining that the serpent-decorated cup in NT 68:21E is to be understood (by the viewer) as appearing (to the victim) so menacing as to provoke resistance, despite the fact that Christ himself assumes the role of the Good Samaritan? In Blake’s work in general there are of course many positive images of serpents, but as Essick and La Belle have remarked, none of the serpents in the Night Thoughts designs that precede the Good Samaritan design exhibit positive characteristics: those in NT 25 and 27:7E are no more promising than the worms in NT 29 and 60:19E. And with the exception of one neutral manifestation of the serpent as ouroboros in NT 257, all subsequent serpentine forms in both Volume I (NT 78, 79, 163) and Volume II (NT 296, 307, 312, 345, 349, 358, 361, 366, 368, 369, 380, 442, 486, and 496) are represented as unmistakably evil. As for cups associated with warnings, the overturned cup of Belshazzar in Night Thoughts 19E: 60, an engraving closely preceding the Good Samaritan design, NT 21E: 68, bears no sinister decorative mark. But the snake-inhabited cup of Silenus in Night Thoughts 380: VIII, 34 (illus. 4 and 5), casts retrospective doubt on the cups of Friendship that once were tippled by the late Philander and his drinking companion, Young himself, as shown in the watercolor verso design for the Good Samaritan episode, NT 69. But the huge grape vine, the source of “the generous blood / Of Bacchus” (II, 595-96) formidably over-arching the scene, ought not to be trusted to affect everyone so happily. By Night the Eighth Lorenzo! (“Man of the World”) is having a drinking problem and is about to lose “a new Eden . . . by [his] Fall” (NT 379, VIII, 568-69). The ultimate source of all dissipation is revealed to be “Mystery,” the Whore of Babylon, who is featured on the titlepage for Night the Eighth (NT 345), in some distress, displaying her cup that contains the blood of the saints. But the earthly source of the treacherous blood of the grape is featured in NT 380: we are shown a huge grape vine that produces a goblet of debauchery that is being held out, to the viewer, in the left hand of the inveigling god Silenus who hides his right fore-arm

The audience of the Night Thoughts series understands of course that the ultimate motives of the Good Samaritan in NT 68:21E and those of Silenus in NT 380 are as different as can be. But in retrospect the viewer is again placed in the begin page 79 | ↑ back to top position of the Man Fallen: now we are able to see and feel what confronting a serpent-cup that is being thrust at us would feel like. The admonitory sign of the snake on the Samaritan’s chalice and the active snake in the cup of Silenus (like the one in the cup given to St. John) are semiotically identical: they serve as warning labels like the skull and crossbones on a medicine bottle. Both mark a lethal liquor, whether it is sought in debauchery (as shown earlier in NT 99:29E, or later in NT 409 and 410) or thrust as a cure upon one who (according to Augustinian interpretive tradition) is a type of Adam lost in sin and reluctant to abandon his old faith.

Moreover, there is nothing in Blake’s use of similar motifs outside the Night Thoughts series to support a positive interpretation of any image uniting a serpent and a cup, particularly an egg-shaped cup. At the top right of Plate IV, the most memorable of the many engravings of exotic serpents and eggs in Bryant’s A New System, Or, An Analysis of Ancient Mythology (1774, 1775), a snake makes four coils around an egg, over the inscription: “OPHIS et Ovum / Mundatum.”12↤ 12 This page is clearly reproduced and catalogued in Roger R. Easson and Robert N. Essick, William Blake: Book Illustrator, Vol. II (Memphis: American Blake Foundation, 1979) no. XII, pl. 14, and p. 14. Beside the snake-and-egg is a separate picture of an ellipsoid cup that bears a crescent on the top and is attached to a pedestal base by a flattened sphere and inscribed “Heliopo — litanus.” A blending of these elements of cup-and-serpent could easily produce the proffered ciborium that intimidates the victim in NT 68:21E. The combination of such elements would result in a pretty piece of paganism which, if proffered him, would intimidate the Man Fallen in his weakened condition. This design, whether or not the attribution to Blake as apprentice engraver is correct, is supposed to be related to Blake’s Mundane Shell symbolism (Milton 19:21-25; depicted in Milton 36); the primary allegory would seem to be that the serpent of time controls the finitude of this world. Among Blake’s other pictures there are two problematic depictions of chalices which help to indicate how the Samaritan’s serpentine vessel is supposed to be understood by the viewer. The most decisive is the ellipsoid chalice which appears in conjunction with a serpent in Blake’s fifth design for his second series on Milton’s Comus (Butlin, cat. 528.5, pl. 628). Blake extensively revised this design (dated by Butlin c. 1815) from an earlier version (Butlin, cat. 527.5, pl. 620) executed as early as 1801. A most noteworthy alteration was to introduce at the left side, just behind the chair in which the Lady sits, immobilized, a meager bald barefooted male attendant, the only human-shaped figure in this version of Comus’s rout. The attendant carries a large ellipsoid chalice which in shape closely resembles that proffered by the Samaritan in Night Thoughts 68:21E, except for its small ball on the top (as in Bryant) and the absence of a horizontal line distinguishing the lid from the cup. Clearly this is a chief instrument of Comus, although his command to “Be wise and tast” (line 813) evidently refers to the (unlidded) cup he holds in his own left hand, while almost touching with his magician’s wand the chalice brought in by his attendant. One important detail is not always clear in reproductions: a huge serpent with wide-open mouth and forked tongue springs up from the attendant-borne chalice and undulates along the magician’s wand, ready to fall upon the Lady should she yield to the invitation to partake of Comus’s cup. This cup is immediately seized by the Brothers when, in the next design (Butlin, cat. 528.6, pl. 629), they break up the Banquet, but Comus eludes their grasp and the attendant’s chalice is nowhere to be seen.

Much the same serpentine symbolism is present in the first version of the Magic Banquet (Butlin, cat. 527.5, pl. 620) where, on the edges of the massive chair in which the enchanted Lady is frozen, are carved three naked female figures wound about by serpents. In neither version is the beleaguered Lady able to see the serpents in the service of Comus, but she must understand well enough that there is something more sinister in his stratagems than is revealed in the inviting cup he displays during his carnivalesque[e] spiel. The viewer, who is being shown more of Comus’s machinations than she, should have no doubt as to the ominous meaning of the attendant serpent revealed in the later version. When Blake recast this episode for Paradise Regained, in Christ Refusing the Banquet Offered by Satan (Butlin, cat. begin page 80 | ↑ back to top 544.6, pl. 689), the would-be victim, by contrast, is still on his feet and thus able to reject, with both raised hands visible, the proffered temptation: three doxies, one dressed in scales, who take the part of the cups in Comus.

The other indubitably sinister conjunction of serpent and cup in Blake’s work occurs in his 1809 picture of ultimate evil, The Whore of Babylon (Butlin, cat. 523. pl. 584), in which the cup of abominations held up by this bare-breasted instigator of war was greatly elaborated from the plain version displayed in Night Thoughts 345, the titlepage design for Night the Eighth. The 1809 vessel containing the wine of the grapes of wrath is elaborately embellished with handles made of two serpents that meet by crossing their tongues above the top of the vessel and thence undulate downward and coil around its stem, where their tails intertwine.13↤ 13 Blake appropriated this vase with serpent handles from James Gillray’s print of October 1805, entitled Matrimonial-Harmonics, in which similar vases are displayed on the mantlepiece of an unhappy family. See Draper Hill, ed., The Satirical Etchings of James Gillray (New York: Dover, 1976) no. 87 and 133-34. The seven-headed Behemoth that carries the Whore and leads the carnage was adapted by Blake from his own earlier visions of Nebuchadnezzar[e] (e.g., MHH 24, NT 299) and of the Beast. Also, I think, from Gillray’s print of 1798, New Morality, in which Leviathan as the Duke of Bedford is drawn ashore as the most imposing figure among the foolish celebrants of the latest French religion. This two-foot wide print (BMC 9240) is clearly reproduced, though lacking the detailed inscription, in Draper Hill, Mr. Gillray: The Caricaturist: A Biography (London: Phaidon, 1965), pl. 74 and 69-70. More current reproductions by Bindman (1989), Johnston (1998), and Magnusson (1998) likewise present only parts of Gillray’s broad and extremely particularized picture. With the aid of a magnifier the whole of Gillray’s masterpiece is visible in John Miller, ed., Religion in The Popular Prints, 1600-1832 (Cambridge: Chadwyck-Healey, 1986) no. 100, 260-61. The side of this chalice exhibits women dancing; eight female spirits with drinks and horns effuse from the top of the cup and zoom over the Whore’s head and down her side to incite and join in the militant revelry on the ground; at the left, a ninth female just by the browsing head of Behemoth exhorts and celebrates this appalling spectacle of carnage. At a finer level of detail, probably too fine to have interpretive significance, the criss-cross pattern of wires that holds together the bracelet and anklet bangles of the Great Whore notably resembles the pattern carefully inscribed on the (visible) lower part of the Samaritan’s proffered chalice (in NT 68 and 21E, illus. 1 and 2). Both this picture and the Comus design present encounters in which the deployers of serpent vessels are certainly up to no good and should be resisted by their intended victims.

Blake’s victim in NT 68:21E has not been enchanted and is thus able to signal that he is just saying no. His right hand (his left arm is almost hidden by his body) is raised, palm out, at a 60° angle, with the fingers almost straight up in relation to the hand. In his half-dead condition, this is the most forceful gesture of rejection he can manage as, alarmed, he rouses himself to support his weight on his right fore-arm. According to Heppner, who bases his remarks on Blake’s engraved version only, “The victim’s response is not to be read as a rejection; he is simply very, very surprised.” In disagreement with Margoliouth, Essick and La Belle, Magno and Erdman, and me in interpreting this gesture, Heppner refers to a compendium of hand signals in Bulwer’s 1644 Chirologia, which I believe to be an inapt model; similar gestures in Blake’s own work, especially in Night Thoughts,14↤ 14 The effort to match the gestures of Blake’s figures with those in a standard handbook is not, of course, invalid, but in life, art, or on stage, gestures must be understood in relation to cultural or individual idioms of expression. Unless the viewer sees the rest of the body language of any figure, as well as other signs, such as words, the viewer is liable to misinterpret what the hands, considered by themselves, are saying. Yet at some junctures hand gestures may be the crucial signs. From the several pages of the Chirologia reproduced in Janet Warner’s Blake and the Language of Art (Kingston and Montreal: McGill-Queens UP, 1984), esp. 50-51, Heppner singles out the gesture “Admiror” (example D on Warner’s page 51), which consists of upraised hands, bent outward at the wrists, indeed, but with the fingers somewhat curved inward toward the palms so that, together, the two hands are gently cupped. The wrist mechanics here are quite different from what can be seen of the stiff-fingered upraised repelling hand in NT 68:21E. A closer comparison on the cited page in the Chirologia appears in example X, “Dimitto,” in which the arm is horizontal and the hand is raised to an 80° angle at the wrist, although here, as in example D, the fingers are bent; the dismissal is a gentle one. The most apposite of the hand signals from Chirologia represented in Warner’s book appears at the leftmost bottom of the facing page (50, pl. 23) as example W, “[Exe]cratione repellit” (partially concealed, unfortunately, in the reproduction), in which the relevant gesture of extreme refusal is expressed with both hands to signify the intensity of rejection. The gesture is shown straight on, not in profile as in NT 68:21E, as it would appear from the perspective of the one being repelled, and the hands, with three of the fingers tense and straight, appear to be raised to a 90° angle from the horizontal forearm, which has no weight to bear. provide a better basis for comparison. For example, in the design immediately following in the engraved series, NT 22E: 71, a virtuous man on the point of death uses a similar gesture as he tries gently or feebly to discourage the vain importunities of his anxious friend. For an escalation of rejection see NT 73, where the Good Old Man tries to fend off intimidating Death, and Job 6, where the agonized victim attempts, in the first version (Butlin, cat. 550.6, pl. 702; cf. 550.9, Eliphaz) with one (visible) hand raised and in subsequent versions with both visible (e.g., Butlin, cat. 551.6, pl. 738) to ward off the oppression of Satan, who is smiting him with sore boils from a vial of infections. In all versions of Job 11, where the recumbent hero is oppressed by a dream-Vision of Satan impersonating the God of damnation, Job is able to raise his hands to repel this hovering incubus who is the negation of God in Elohim Creating Adam (Butlin, cat. 289, pl. 388). Unwise rejectionism more emphatic than that in NT 68:21E is, on the contrary, exhibited by the recumbent rationalist in NT 42E:153; this Lorenzo twists away while holding out a stiff left arm with raised hand to repel male and female spirits who had offered him their good advice. But the most emphatic rejectionist among the wounded begin page 81 | ↑ back to top figures who are lying down in Blake’s Night Thoughts appears in NT 152, an unengraved recto design that just precedes. In it the male spirit of Young dives down, with proffering cup in each hand, only to have the frantic sick man, stung by the “Venom” (IV.767) of Death, turn away and “push our Antidote aside.”15↤ 15 Heppner’s citation of Blake’s early drawing entitled Robinson Crusoe Discovers the Footprint in the Sand does not support his interpretation of the victim’s gesture in NT 68:21E as non-resisting. In the text Heppner quotes, Crusoe is not only “exceedingly surpriz’d,” he is “Thunder-struck,” as if he had “seen an Apparition.” Indeed, Heppner himself endorses a comment by Rodney M. Baine which mentions Crusoe’s “isolation and horror,” causing him that night to sleep “not at all” (Heppner 69n18). In looking out across the sea at some unrepresented cause for apprehension appearing to him (but not to the viewer), Crusoe is the precursor of many other Blake figures terrified by some unseen horror offstage: Bromion, for example, in the frontispiece to Visions of the Daughters of Albion. Three of the seven heads of the Beast in Night Thoughts 345, the titlepage design for Night the Eighth, entitled “Virtue’s Apology: or ‘The men of the World answer’d. . .,’” also look off at some ominous vision and their passenger, the Whore, raises her hand in distress at something at the right that she can see but we are not shown. The Miser in Night Thoughts 115 (IV, 6) does the same thing. Those splayed fingers of Blake’s Robinson Crusoe, expressing extreme apprehension or horror, are displayed in a posture resembling that of the younger man being accused and sent into exile in Night Thoughts 160 (v, dedication), on the second titlepage for Night the Fifth, “The Relapse.” This man’s arms, almost exactly like Crusoe’s, are held rigidly down and, though his fingers are not as splayed, his hands are stiffly spread out at right angles. He is horrified: his hair stands on end, his eyes pop out, and he shouts at receiving his sentence from the implacable old man, whose head rather remarkably prefigures that on the so-called Nebuchadnezzar Coin (Butlin, cat. 704, pl. 919) drawn more than 20 years later. Like this figure, like Robinson Crusoe, and like the woman discovering the dead child in “Holy Thursday,” plate 33 of Songs of Experience, the victim in the Good Samaritan scence is expressing horror and, since he is lying down, his gesture also serves to fend off what is about to be thrust upon him. But the victim’s refusal, even at its most extreme, in NT 68, is not as conclusive as that of the foolish girl in “The Angel,” plate 41, of Songs of Experience. Too long ago she rejected the possibility of joy. There may still be hope for the Man Fallen. Later, in Night the Eighth, NT 358, a horrified male traveler with his hair standing on end, who encounters a huge rearing serpent poised to strike, raises both of his hands, wrists up, fingers splayed, to fend off the attack. Allowing for the difference in the physical situation of the Man Fallen Among Thieves, the hand gestures of all these male figures are similar, expressing their attempts to repel things unacceptable or menacing.

Thus, at the instant Blake illustrates, in NT 68:21E (illus. 1 and 2), immediately before the curative liquid is to be dispensed, the wounded man—believing that no Jew can expect any good thing from the hand of a Samaritan—would be reading aright the sign of the serpent according to the codes he has been taught to trust. In choosing to set the parable in this moment, and to embellish the story with other details not mentioned in the parable itself, Blake becomes the first artist in 18 centuries to depict this episode in the parable of the Good Samaritan from the point of view of the Man Fallen Among Thieves, on first encountering his presumably hostile neighbor. Blake employs the sinister image of the serpent to challenge the viewer to imagine afresh the victim’s response to this unexpected and dubious source of help, even though appearing in the form of Jesus himself, within the framework of the parable’s powerful ethnic antagonisms: Isn’t it enough that I’ve been mugged and left for dead in this god-forsaken crime-infested alien territory, on a notoriously dangerous stretch of road, where even the clergy I believed I could trust won’t stop to help me? Now on top of all that, here comes this traditional enemy of my people, a Samaritan, offering who-knows-what in a snake-decorated vessel. NO THANKS! It is no wonder that Blake depicts the victim (especially in the watercolor version) with his eye-brows shooting up, his mouth open, terrified, straining to lift his head and upper body from the boulder behind him, mustering the last ounce of his ebbing strength to raise his hand just off the ground, palm-out at the wrist, to fend off his would-be rescuer and signal his aversion to whatever snake-oil this suspicious-looking Samaritan medico wants to thrust upon him. The alarmed reaction Blake depicts here is even more striking in comparison to the lack of expression in the often-unconscious or barely conscious inert victims depicted by other artists. Indeed, one of the few artists other than Blake to depict the victim (later in this episode) with an animated expression is Hogarth, who, in the mural in St. Bartholomew’s Hospital (illus. 8) represents the injured man, grimacing in pain, his fist clenched, staring dazedly ahead as the Samaritan pours oil into his chest wound. But the victim in Hogarth’s painting is not exhibiting fear; he has already allowed his extended left arm to be bandaged.16↤ 16 It cannot be supposed that Blake did not trouble to study the great Hogarth Good Samaritan (of 1736) on the second flight of the staircase at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, near St. Paul’s. Even more certain is that Blake was aware of the picture as ably engraved in 1773 by Ravenet and Delatre, since it was included in the Hogarth 100-print portfolio of 1790 to which Blake contributed his own fine engraving of Hogarth’s The Beggar’s Opera. It should be understood that one reason that Hogarth’s Good Samaritan is not now better known, or indeed, well discussed, is that it is situated on the wall of a staircase and, except from above, is almost impossible to photograph as a whole. The viewer who lacks the print or cannot move up and down the stairs and lean back on the rail may not take in the figure of the Levite who, with his nose in a text—doubtless biblical—is wandering to the left in the boscage. This can be confirmed in Ronald Paulson, Hogarth, 2: 83-86 and (uncolored) pls. 39 and 41. As Paulson observes, the garments of Hogarth’s Good Samaritan and those of Christ in The Pool of Bethesda, which is positioned at right angle to the Samaritan picture, are similar, but this should not be taken to signify that these two figures are identical. Hogarth’s point is that the Samaritan is performing an exemplary Christ-like act, but not that what is shown in the two pictures is equivalency, yet another case of Christian typology. Hospital doctors should do well but cannot guarantee to perform miracles. One feature of particular interest to Blake’s Good Samaritan picture is that in Hogarth the encounter takes place just in front of and beneath a nearly dead tree which, however, has a few leaves on twigs that extend just above the Samaritan who performs the healing. A parasitic growth of ivy on the lower trunk does not reach high enough to cover the broken-off main trunk, which twists to the left, pointing in the direction of the arrogant Priest and his groveling devotee, who are enacting their forms of worship near the top of the road. On the other side, the Samaritan’s horse is tethered to a (dead) branch of the tree that protrudes from a mass of ivy on the trunk. In such details one can observe motifs that Blake was able to redeploy in his quite different realization of the parable. Due to pictures of the Bassani and Rembrandt the dog had become such an established presence in the iconography of the Good Samaritan that Hogarth needed no other prompting to include his own favorite animal in his, the largest, of Good Samaritan pictures, doubtless in part because the “beast” of the parable seemed sufficiently accounted for by a horse or other equine that could carry the victim. One would not wish to argue, however, that Blake meant something by not including a dog in his Good Samaritan pictures. Some of these matters are discussed by Ronald Paulson in Popular and Polite Art in the Age of Hogarth and Fielding (Notre Dame, IN: U of Notre Dame P, 1979) in chapters “The English Dog,” 49-63, and “The Good Samaritan,” 157-71.

Other unusual details of the Blake’s portrayal of the Good Samaritan story take on added significance in relation to Young’s text. As Heppner observes, the parable of the Good Samaritan “does not exactly illustrate” Young’s drift; on the begin page 82 | ↑ back to top contrary, Blake’s depiction of a completely gratuitous act of kindness, from which no return is expected, constitutes an implicit critique of the line marked for illustration: “Love, and Love only, is the loan for Love.” Heppner cogently notes the aptness of the parable as a correction of Young’s reliance on blatantly commercial imagery:

A true neighbor does not simply return love for love, or buy love by lending or giving love, but freely gives love to those most culturally remote when they are in need, even if they have shown nothing but scorn in the past, and are not likely to change in the future, and may have no occasion to return that love. (1995, 169-70)

This point was missed altogether by the anonymous writer of the Explanation of the Engravings in 1797, whose uncritical adoption of Young’s monetary imagery makes it seem that the Good Samaritan’s deed somehow balances the books on love and thus serves to illustrate an unassailable moral principle.

And the commercial imagery in this part of the poem is even more egregious than Heppner’s summary suggests. The voice of the author has been obsessively addressing one Lorenzo, traditionally identified with Young’s nephew, a character who is not very clearly delineated through thousands of lines but who is almost everywhere (as in NT 380, as said; illus. 4 and 5) presumed to be unregenerate. Young’s exhortations seem to prevail occasionally in leading this sinner to repentance, but it is not until halfway through the

The subject of friendship, about which Young the narrator has been haranguing the recalcitrant Lorenzo in the latter part of Night the Second, is at first sharply distinguished from anything to do with money—but only in the unconvincingly banal imagery that is typical of much of the poem: “Their Smiles the Great and the Coquet throw out / For Others Hearts . . . / Ye Fortune’s Cofferers! Ye Powers of Wealth! . . . Can Gold gain Friendship?” (II, 563-34, 566, 569) etc. But then, pivoting on the marked line, “Love, and Love only, is the loan for Love” (II, 571), Young enthusiastically switches the valuations in his discourse, revealing the authorial presence to be, as so often in Night Thoughts, on both sides of the question. Given the monetary context Young has established, it is no wonder that the author of the Explanation of the Engravings, extrapolating from Young’s own words, describes the “Loan” for love, or the interest charges, as an outright “purchase.” On the previous page Young had asked Lorenzo to “pardon what my Love extors, / An honest Love, and not afraid to frown” (II, 556-57), Friendship, for Young, is discussed as a commodity requiring in-kind payment (or emotional extortion), according to what Heppner rightly calls the “impoverished doctrine” that Lorenzo cannot “hope to find / A Friend, but what has found begin page 83 | ↑ back to top

In the next paragraph (overleaf, p. 38 in the engraved version), however, Young undermines his own counsel without realizing it. He has been urging Lorenzo to repress his pride and take a chance on friendship. Now, in the next breath, he advises caution: Friendship is such an easily damaged luxury item (“Delicate, as Dear,” II, 577) that “Reserve will wound it; and Distrust, destroy” (I, 579). Since Lorenzo would be taking on a lifetime commitment, as exemplified by Young’s own 20-year relationship with the now-dead Philander, it is wise to “Pause, ponder, sift” (I, 584). Only after a thorough background check, apparently, can it be affirmed that “A Friend is worth all hazard we can run” (I, 589). All these contradictory images and nuggets of advice, and most particularly Young’s high-handed way of attempting to impose them upon an unwilling Lorenzo, enter into Blake’s use of the Good Samaritan parable as a critique of Young’s thinking on “Friendship”—the third announced subject of Night the Second. But in itself the Good Samaritan parable is best understood as conveying a lesson in disinterested charity towards one’s neighbor, of whatever persuasion, rather than as an expression of “love” for one’s friend.

Once it is recognized that Blake’s application of the parable to Young’s text turns on the victim’s resistance, the unusual details of the design fall into place, linking two iconographic features which have no obvious connection with each other: Jesus’s appearance as Good Samaritan and his use of a vessel recalling the serpent-charged chalice of St. John. Given the cultural context, the conscious victim’s acceptance of this object from this man would be foolhardy—or it would require an extraordinary act of faith, a conversion. It is the latter issue that Blake is getting at here. The ethnic and religious antipathies that underlie the standoff depicted in Night Thoughts 68 are reinforced by the symbolism of the two huge overlapping trees behind the central figures: the one at the left apparently dead, a barren branch drooping over the side of the wounded man; the one at the right abundantly alive, spreading its flourishing leaves over the Good Samaritan and beyond.

The trunks of these two trees are as realistically represented as any Blake ever made, but how these trees are interrelated is quite beyond arboreal relationships to be found in nature begin page 84 | ↑ back to top and thus points to their symbolic import. Beneath the text panel the trunk of the tree at right emerges from the ground behind but touching the trunk of the tree at left. Especially in the engraving, NT 21E (illus. 2), the bark on the trunk of the tree at right is striated, establishing itself as being of a distinctly different species. In nature the two could not possibly have grown together in such proximity to the massive heights indicated. More extraordinarily, the tree at right becomes bifurcated, as it emerges above the text panel in front of the tree at left; the huge trunks must have crossed behind the text panel.