review

begin page 29 | ↑ back to topFrançois Piquet. Blake and the Sacred. Paris: Didier Erudition, 1996. 450 pp. illus.

François Piquet is a renowned scholar in France where he teaches English romanticism at Jean Moulin University, in Lyon. Among his publications that focus on Blake’s poetics, Blake et le Sacré seems to be an elaboration of his doctoral dissertation of the same title (Clermont-Ferrand, 1981).

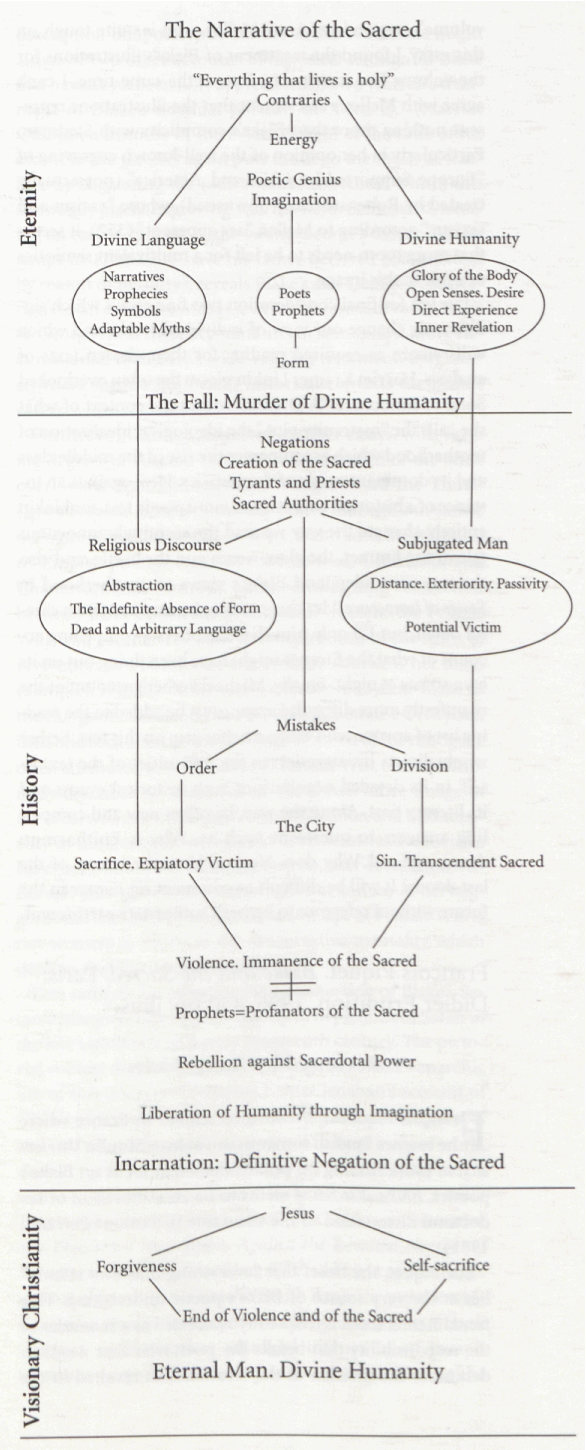

For Piquet, the belief that “everything that lives is holy” lies at the very source of Blake’s poetic undertaking. This fundamental truth is frequently reasserted as a reminder of the responsibility that befalls the poet, who first needs to denounce the division of the creation that resulted in the subordination of human beings to a dead religious language informed by abstract and arbitrary categories. He also has to revive the language of prophecy, invoke the original power of the word and thus rid modern existence of the tragic errors provoked and maintained by the sacred. Eventually, he is required to highlight man’s ability to redeem himself, and escape from the sacred through exertion of responsible freedom.

Yet, the reader cannot but face a difficulty: how can Blake praise the holiness of existence and abhor the manifestations of the sacred in modern life? His whole work strives to demonstrate that these two positions are not contradictory but that the first one calls for the other. It is essential for the reader to become aware of the danger entailed by a confusion of the holy and the sacred—which the poet holds responsible for much of modern corruption. The problematic of the sacred chosen by Piquet in Blake et le Sacré thus proves to be a very useful key to the understanding and unraveling of Blake’s works.

Piquet opts for a diachronic study that could render the conscious evolution of the poet’s sensibility regarding the sacred; for if Blake was positive that the key to human fulfillment resided in the recovery of holiness, he was aware of the difficulty of the task and still had to devise the means to attain his goal. Piquet realizes a very insightful study of the poet’s major influences and of their incorporation into the canon; the failures of the Gnostics or Milton, for instance, are important to Blake in that they allow him to reflect on the pervasive presence and resilience of the sacred. However, I sometimes regretted that Piquet devotes too much space to the presentation of philosophical or theological theories instead of focusing on a closer analysis of Blake’s poems—especially since he is just as thorough and acute when he abandons his theoretical style for a more poetic one, fraught with telling imagery.

The sacred is the common link between the fragmentation of individual psyche and a more collective awareness of historical fluctuations and ideological upheavals. Blake’s crusade would, however, remain incomplete were it not accompanied by the creation of a new poetic form or medium able to combine energy and reason. His myth making does not so much aim at destroying religion altogether or at proposing another religion which would merely crown different figures of authority—since Christ is pictured as the ultimate savior of humanity. Rather, the artist casts a different light on Christianity, as René Girard did almost two centuries later when he composed a ground-breaking interpretation of the New Testament as anti-sacrificial;1↤ 1 In La Violence et le Sacré, Paris, Grasset, 1972 and Des Choses Cachées depuis le Commencement du Monde, Paris Grasset, 1978. for the Christian scholar the death of Christ interrupts the cycle of violence and abolishes the sacred installed by traditional religion. Piquet’s biggest contribution lies in the parallel he begin page 30 | ↑ back to top draws between the works of the two authors: both defend a religion in which the sacred plays no role. The sacred needs not only to be altered but also to be dismantled, uprooted as it were; yet, in order to do so it is necessary to understand its source, workings and metamorphoses through a genealogy of the sacred.

The first part of Piquet’s study focuses on Blake’s interpretation and re-creation of Genesis as a genealogy of the sacred. Holiness refers to the inherent nature of life and creation as an indivisible compound of contraries, whereas the distinction between the profane and the sacred is a human construction inherited from the Fall and denies the principle of holiness. In Blake’s opinion this division has ruled and restricted man’s existence for centuries by keeping him on an historically bound path, leading away from the eternal realm of Divine Humanity. Driven by a desire to restore life to its original holiness, Blake engages on a visionary journey against the constraints of the sacred—one manifestation of which is religion.

Piquet insists that most of Blake’s poems are informed by a double perspective (85). The historical one is dictated by a theological tradition that professes a belief in a jealous God, while the second places the narratives in the sphere of eternity by recording the forgiving voices of visionaries who call for the annihilation of religious institutions. The rift that separates history and eternity materializes a dramatic tension between man’s alienation in the present world and his liberation from the sacred in a prophetic future. Only through vision and imagination can man exploit his ability to recreate the world against the encroaching attacks of the sacred and experience his primordial double nature as an eternal and historical being. Imagination is a direct link to God; and what is more, it is an act with God (46). Yet, this mode of being has long been abandoned; poets and prophets have been silenced and have learned to revere stability and permanence.

In the prison of the sacred, chains are not easily broken; individuals who escape its careful grip are irremediably caught up by a tight and merciless net of authority (118), petrified and used as staunch protectors of the religious (133), or, in Piquet’s words, as ramparts of the sacred (“remparts du sacré” 369), which are turned into a paradoxical display of force and of its limits. Once it is created by man, the sacred becomes a simultaneous source of order and disorder: it limits violence yet justifies a certain and constrained use of it. Thus Orc can never be more than an embryo of hope, a promise cut short. However, he has voiced his revolt against the system before being lured back into the historical cycle of violence, thus paving the way for other prophetic figures.

For Blake, one necessary step towards redemption is the acknowledgment by man of the coexistence of good and evil in himself; both are as intricately linked as the events of the Fall and the creation of man. Denying the “dark” side of

begin page 31 | ↑ back to top human nature jeopardizes the overthrow of the sacred by slackening the necessary tension towards mercy. Blake inscribes Jesus in a space determined by continuity and difference; his Christ never renounces his propensity to rebel against the satanic negation of evil and maintains his Divine Humanity by refusing to play the fatal game of the sacred. He alone can undo the divisions artfully created by religious and political powers. As the most human form of God, the junction point of historicity and eternity (166), he alone can free humanity and enable its progressive resurrection in Eternity (152). The challenge his very incarnation represents does not vanish but is made more blatant with his death: his self-sacrifice reveals how heavily religion relies on violence and arbitrary distinctions. While Orc’s Poetic Genius had been subverted into anger and thirst for revenge and therefore only buttressed the edification of the sacred, Jesus manages to erase the consequences of the Fall by translating his Energy into Forgiveness.In the second part of his essay Piquet looks at Blake’s attempt to define the premises of a new order, outside the stronghold of the sacred, in recent poetic or theological enterprises. Blake and the Gnostics share the belief that redemption from the decaying state enforced by the sacred is possible through knowledge. They nevertheless diverge on both the nature and the means of attaining this knowledge. Blake contends that the roots of religion are to be found in the death of prophecies and their replacement with abstract reasoning—which the Gnostics have turned into an idol. Visionary imagination alone is capable of allaying the poet’s phobia of dissolution of form (173): Los—inspired by the Divine Vision—starts building Golgonooza against the chaos of the infinite. However, unlike Christ, he is not the Divine Vision (362) and can merely hope to prepare the ground for the return to eternity. The power of prophecy merges the divine and the human; in an ultimate manifestation of Divine Forgiveness, it prevents man’s fall from being complete.

In attempting to eradicate sin through stability and order, Urizen indulges in a satanic mistake: the reiteration of the myth of creation (201). The tyrant puts an end to man’s relation to the divine by obscuring his original visionary faculty with the weaving of the net of religion (187). In his engraved illustrations to The Book of Job Blake depicts God’s metamorphoses into a masked satanic Deity. As Piquet points out, Satan contributes to the hidden strength of the sacred by imposing his own will onto God (plate 5); on plate 11 it is no longer possible to tell the two figures apart. Only on plate 17, when God is joined by Jesus, does Satan relinquish his hold on Divinity (204). In other words, God’s true reign can only begin when his humanity is confirmed, and the boundary between the sacred and the profane dissolves. For Piquet, it is not the spirit of Jesus that dies on the cross; rather it is the condemning God that has kept his creature at a distance thanks to an unwholesome pact with the Prince of Darkness (215). The Passion calls for the revival of Divine Humanity: not only man, but God himself is saved from abstraction.

In the fourth chapter, Piquet analyzes Blake’s rehabilitation of the sublime; the poet wishes to rediscover its prophetic sources and cleanse it from the meaning it has unfortunately assumed as a metaphorical substitute for a Reasoning God. The Book of Urizen delineates the paradoxically increasing distance between man and God. While in the eighteenth century God’s laws were accepted as known, they also served to keep people away from his being. When God ceases to participate directly in man’s experience, the divine become indecipherable, distant and sacred. For Blake, however, nothing is ineffable; God is the non-other, the very manifestation of immanence.

Blake regards Sublime Art as a response to corrupt religion: it begins by urging a radical questioning of God’s essence (his role as a legislator is undermined while his function as a creator comes back into the foreground, 222) and proves useful in deconstructing the sacred. Piquet characterizes the sublime as a creative energy gaining momentum each time God distances himself from man’s experience; it operates as a warning against a colonization by the sacred. While sublimation is but the perversion and repression of sexuality, the sublime reveals that our body is what our senses perceive of our soul. It abolishes the distinction and hierarchy between the two. For Blake, the advent of true civilization corresponds to man’s assertion of his divinity through the invention of a political and poetic form which combines the senses, reason, imagination and will.

Blake’s Divine Order is based on a tension between mercy and judgment; therefore it is neither static nor hierarchical. The poet fears that Providence will be turned into predestination each time it operates against man’s will (270). Blake accuses Milton of participating in the reinforcement of the sacred by committing several satanic mistakes, among which are the repression of evil’s voice, the creation of exteriority, the division of the poetic and the political, and the confusion of individuals and states, of the sinner and his sin (276). In Milton, Blake expresses his staunch conviction that each individual needs to go through the phases of incarnation, passion and resurrection if the sacred is ever to be dismantled (291).

In the third part of his book, Piquet illuminates Blake’s notion of holiness with Girard’s conclusions on the sacrificial roots of the sacred. Cities play as central a role in Blake’s construction of a visionary universe as in other myths and cultures. In the Bible, cities are always founded on murders and also prevent violence from spreading. Everything from cultures to the sacred begins and ends in cities: the construction of Jerusalem is the last act of divine history (300). God’s city is the eschatological meeting point of nations; it exemplifies consciousness turned towards the world and no longer towards the self (305). Building a city in a fallen world—as Los does with Golgonooza—is bound to consolidate the sacred at first but may end in its overthrow.

begin page 32 | ↑ back to topThe ambivalence of the circumscribed urban space—simultaneously blessed and cursed—echoes that of the sacred (source of order and disorder). The relationship between the two terms goes well beyond a formal analogy. Each is the source and consequence of the other, and each depends utterly upon the other. The city’s survival requires sacrifice and sacerdotal power; the survival of the sacred needs a fixed point of reference acknowledged by a community. Violence is simultaneously the object of the law and its means of enforcement. Murder is then perceived as divine and necessary; it inaugurates a new sacred based on the collective murder of an expiatory victim (311). In the Bible violence is no longer concealed but made visible. Its order does not exclude crisis altogether; rather, it relies on a constant reinforcement of its authority through interdict and rituals. For Girard, these two elements precede the advent of a culture: they keep the sacred at a distance while ensuring that it is visible to the community. Sacrifice being thus legalized, self-destruction becomes forbidden and unnecessary. Through ritualized sacrifices, revenge is transferred to the higher power of God disguised in transcendence (334). As a result, man’s responsibility in violence is concealed, and so is his ability to put an end to it.

The true role of religion is now unveiled: it keeps violence within controllable distance. Girard insists that the eighteenth-century ideal of a Natural Law was not only an illusion but also petrified man in a state of alleged innocence, an idea which reverberates throughout the Blakean canon. This error results in a heightened repression of human dual nature and the survival of a dehumanizing structure. Deprived of dialectic which fosters forgiveness, man is bound to remain in the net of the sacred; he is then required to forsake his prophetic faculty and consent to turn violence against exterior enemies. With Jesus—born from and for forgiveness—divinity ceases to impose violence. Man’s responsibility for the violence of the sacred can no longer imputed to God.

Blake argues that Redemption is the work of man only; yet he is also convinced that Jesus was the only being capable of renewing a privileged relation to the divine. God for him was knowable in his son only (394), since the latter was neither profane nor sacred. Neither was he the product of a theological construction. What Blake resented in religion (Christianity as taught by theologians) was the veneration of a dead God rather than of the Divine Humanity. Girard’s theory emphasizes the contradiction between Christianity and the classical idea of religion based on a separate sacred order. For him, incarnation is a definitive profanation of the sacred (401): God sacrifices himself, assumes man’s misery until death in a formidable gesture of forgiveness. As Piquet points out Blake evolved towards a very similar perception. He had equated the crucifixion with the humiliation of man in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell but interprets it as a sign of self-sacrifice in Jerusalem.

According to Girard and Blake, Christ’s death is a voluntary gesture of acceptance of the city’s violence. With his blatantly unjust death—in which the sacred does not play any role—Jesus urges man to cease uniting around a sacred murder. It is now impossible to deny its workings within the urban space. The Son of God has shown the right approach to existence by focusing not on the sin but on the ability to forgive; imagination is concretely translated into forgiveness which in turn deprives the sacred of the fascination it exerted (416).