MINUTE PARTICULAR

The Night of Enitharmon’s Joy

It was Martin Butlin who first brought to our attention the importance of the late Gert Schiff’s catalogue entry on the color-printed drawing formerly known as Hecate, which was published in Japanese in the catalogue of the exhibition of which Dr. Schiff was Commissioner: William Blake 22 September-25 November 1990 (Tokyo: National Museum of Western Art, 1990) 137-38 (see G. E. Bentley, Jr., Blake Books Supplement 308-09). Dr. Schiff wrote the majority of the entries (with about one quarter supplied by Martin Butlin) and, in the second edition only, an introductory essay. The entry has therefore remained unread by most Anglophone readers, but it deserves to be widely known in the world of Blake scholarship, as it advances a very interesting hypothesis as to the significance of the design, and retitles it accordingly. We are therefore grateful to Martin Butlin for suggesting that we publish it, and to Robert N. Essick for lending us Dr. Schiff’s English text and for providing several points of information. For permission to print the entry, we wish to thank Chief Curator Akira Kofuku and the National Museum of Western Art, Tokyo, and, for permission to reproduce Hecate, Deborah Hunter, Photographic and Licensing Manager, National Galleries of Scotland. We are also grateful for the assistance of David Weinglass, Chris Heppner, Richard Bernstein, and Beth Mandelbaum.—MDP

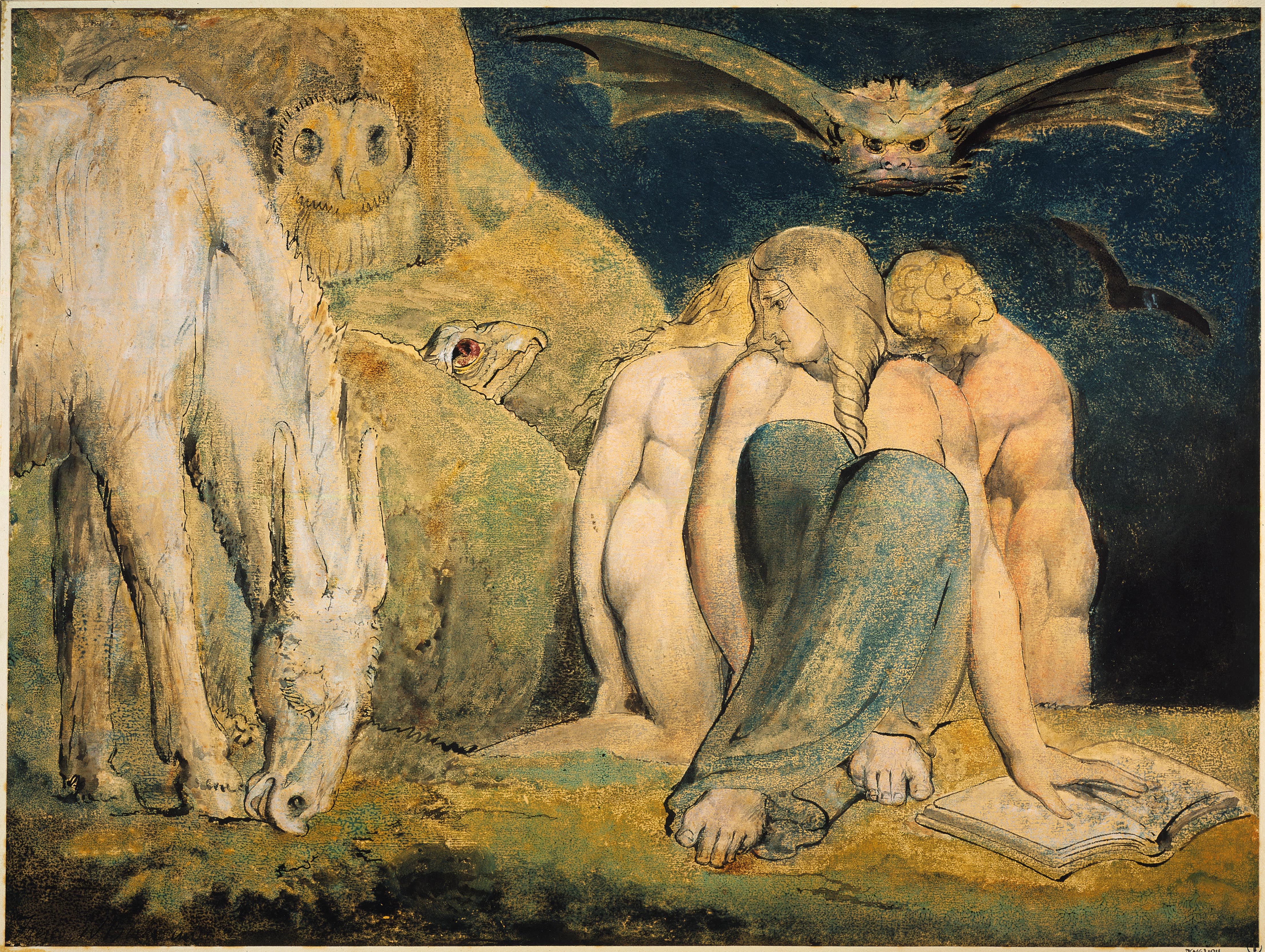

‘The Night of Enitharmon’s Joy,’ formerly called ‘Hecate’ c. 1795

Color print finished in pen and watercolor, 43 × 57.5 cm. Signed “Fresco WBlake inv” b.l.

Probably the second pull after the first one in the Tate Gallery (Butlin 316)

Literature: Butlin 317

The National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh

Blake left this print untitled, and it has been known to generations of scholars under Rossetti’s misnomer of “Hecate”—notwithstanding the fact that this classical goddess is invariably depicted with three conjoined bodies, their faces turned outwards, in the directions of three branching crossroads. Hagstrum and, following him, Jones, noticed that instead Blake’s group consists of three separate figures: a mature woman, sitting with raised knees and partly eclipsing the facing bodies of a girl to her left and a boy to her right. Both authors derived specific interpretations from this observation. Hagstrum (1970, p. 329): the two figures are separated by the goddess of jealousy; Jones (1972, pp. 125-129): their innocent love is spoiled by institutional religion. Heppner, who had independently recognized that the figure does not represent Hecate, linked the composition in an exemplary analysis to witchcraft: the central figure resembles the Witch of Endor (The Witch of Endor Raising the Spirit of Samuel, New York Public Library, Butlin 144); the cave is her habitation; the winged animal, her familiar; the book, her conjuring book. She is intent upon a ritual which might be “a dedication of the children to an underworld deity . . . (their) initiation . . . into sexuality viewed as shame and guilt . . . (or) even . . . a premature marriage ceremony conducted under powerful and unfavorable circumstances.” Heppner rightly emphasizes that, since we do not know the underlying narrative—whether it was found or created by Blake—we cannot arrive at his full intention. Yet he concedes that “Hagstrum’s Jealousy and Jones’s institutional religion, both described as separating lovers, seem pointed in a relevant direction” (1981, pp. 355-365). Lindsay concurs with these interpretations by defining the “witchcraft depicted . . . as a Vala-like envy which eclipses vitality by impeding the union of Cupid and Psyche” (1989, p. 29). “Cupid and Psyche” is a figure of speech. More important is the introduction of Vala, Blake’s evil goddess of Nature, for this points at the possibility that the missing narrative might include, in addition to witchcraft, elements of Blake’s own mythology.

It seems highly significant that in all interpretations the function of the central figure is defined as separating the lovers. This holds also for the rites proposed by Heppner. For those barely pubescent children who were initiated into sex through lurid rituals of witchcraft may thereby well have lost their capacity of loving. That the two youthful figures look ashamed was the magic word that freed Heppner “from the encrusted texts through which (he) had always looked at the print” (p. 356). Boy and girl hang their heads as if they hardly dared to look into each other’s eyes. While the boy (only in the present copy) raises his arm in a half-hearted attempt at a caress, the girl keeps her hand obediently behind her back. The woman’s demeanor is expressive of the most perfect indifference. Her mind is neither with the children nor with her menagerie—a sign that both are safely under control. Only in the Tate Gallery’s copy does her forefinger point at a particular spot in her book; in our and in the Huntington version, her hand rests aimlessly—yet possessively—on the page. In the Tate copy she stares at nothing in particular; in the present pull one imagines her sight becoming blurred; in the remaining one, her eyes are closing with sleep.

Two observations in the literature point in the direction where, according to my own reading, the subject might be found. Several writers (Bindman 1977, p. 100; Paley 1978, p. 38; Lindsay p. 29) notice that the book with its blurred writing is none other than Urizen’s Book of Brass, in which he codified his repressive law (cp. Butlin, pls. 329, 378, 380, and Erdman, TIB, pp. 183, 187). Bindman, while still considering the figure as “Hecate,” notes that “the mystery and begin page 39 | ↑ back to top

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

The likeliest explanation of this print is, I think, that it allegorizes Enitharmon’s scheme to enslave mankind by way of sexual repression:

Now comes the night of Enitharmons joy!There could be no better visualization of her resolve to “separate male and female in every civilization” (Bloom 1963, p. 151) than this group of three. For under this premise it is obvious that the young lovers are bewitched by Enitharmon’s ban on sex as enforced by her adoption of Urizen’s book. By depicting Enitharmon as a brooding witch, Blake shows that both her religion of chastity and her promise of an afterlife are nothing but evil spells. And how well does the figure’s somnolence fit her impending, world-historical sleep!

Who shall I call? Who shall I send?

That Woman, lovely Woman! may have dominion?

Arise O Rintrah thee I call! & Palamabron thee!

Go! tell the human race that Womans love is Sin!

That an Eternal life awaits the worms of sixty winters

In an allegorical abode where existence hath never come:

Forbid all Joy, & from her childhood shall the little female

Spread nets in every secret path. (E 5:1-9, E 62)

My weary eyelids draw towards the evening, my bliss is yet but new. (E 5:10, E 62)

Works Cited

Bentley, G.E., Jr. Blake Books Supplement. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995.

Bindman, David. Blake as an Artist. Oxford: Phaidon, 1977.

Blake, William. The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake. Ed. David V. Erdman. Rev. ed. New York: Doubleday, 1988.

Bloom, Harold. Blake’s Apocalypse: A Study in Poetic Argument. New York: Doubleday, 1963.

Butlin, Martin. The Paintings and Drawings of William Blake. 2 vols. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1981.

Erdman, David V. The Illuminated Blake: William Blake’s Complete Illuminated Works with a Plate-by-Plate Commentary. Garden City, New York: Anchor Press, 1974.

Hagstrum, Jean H. “‘The Wrath of the Lamb’: A Study of William Blake’s Conversions,” in From Sensibility to Romanticism: Essays Presented to Frederick A. Pottle. London and New York: Oxford University Press, 1970 [1965] 311-30.

Heppner, Christopher. “Reading Blake’s Designs: Pity and Hecate.” Bulletin of Research in the Humanities 84 (1981): 337-65.

Jones, Warren. Blake’s Large Color-Printed Drawings of 1795. Ph.D. dissertation. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University, 1972.

Lindsay, David W. “The Order of Blake’s Large Color Prints.” Huntington Library Quarterly 52 (1989): 19-41.

Paley, Morton D. William Blake. Oxford: Phaidon, 1978.