ARTICLE

Richard C. Jackson, Collector of Treasures and Wishes: Walter Pater, Charles Lamb, William Blake

Jackson the Rich Hermit

When Richard C. Jackson died in 1923, the newspapers had a wonderful time: “Recluse who Collected Everything”1↤ 1. Anon., “Richard C. Jackson: Eccentric Camberwell Recluse who Collected Everything: Died as He Lived,” South London Press, 3 Aug. 1923. said one headline. “Poverty in a House of Treasures”2↤ 2. Anon., “Recluse’s £12,000 Art Hoard: Only 5s. in the Bank: Poverty in a House of Treasures: Rubens Pictures for the Nation,” [no periodical identified, ?July 1923]—this reference, like numbers of others here, derives from a clipping in the Ruthven Todd Collection in Leeds University Library. According to another account, in his latter years, “He would be dressed in a coat, green with age, a pair of shabby trousers, a high wide-brimmed top hat, a pair of old white canvas shoes, and a big red scarf round his neck. This was his attire even in the middle of winter. In later years he never wore a shirt but had his coat buttoned across his bare chest.” [Anon., “Rich Hermit’s Romance. Private Altar Over Garage. Dream Life,” Weekly Dispatch [sic], [?July 1923], quoted from an undated clipping in Southwark Local Studies Library.] said another. “Fortune Given to the Poor” proclaimed a third, and “Imagined Himself a Bishop.3↤ 3. Anon., “Secrets of Rich Recluse: Fortune Given to the Poor: Imagined Himself a Bishop: Gorgeous Robes at his Home Altar,” [no journal identified, ?July 1923].

They said that he was a wealthy, impoverished hermit who was “found dead” in his richly-furnished mansion in Camberwell “holding a partly eaten orange in his hand.”4↤ 4. Anon., “An Eccentric Recluse—Mr. Jackson and Walter Pater,” Times, 30 July 1923: 8. Jackson’s house, at 185 Camberwell Grove, is a detached Victorian building which still survives at the southern end of a crescent, as I was generously told by Mr. Stephen Humphrey of the Southwark Local Studies Library. They said he used to perform mass wearing gorgeous robes in his own private chapel built over the stable, and that he wandered through the seedier streets of South London giving alms to the poor. They said that he was a neglected friend of the great such as Walter Pater, and that he lived on water and a crust and donated his paintings to the National Gallery. Newspapers love eccentrics, and especially rich hermits, and they had a field day with Richard C. Jackson.

Of course the newspapers plagiarized each other shamelessly, and it is exceedingly difficult to determine which, if any, of their reported facts are authentic. Jackson is said to have called himself Brother à Becket and to have worn monastic robes in the streets of London5↤ 5. Anon., “Richard C. Jackson: Eccentric Camberwell Recluse who Collected Everything: Died as He Lived,” South London Press, 3 Aug. 1923. (illus. 1-2). At his death one correspondent said that his house was in an “indescribable condition of filth and neglect,”6↤ 6. Anon., “An Eccentric Recluse—Mr. Jackson and Walter Pater,” Times, 30 July 1923: 8, repeated word for word also in Anon., “Richard C. Jackson: Eccentric Camberwell Recluse who Collected Everything: Died as He Lived,” South London Press, 3 Aug. 1923. and another said: “I visited my late friend to within a few weeks of his death, and I have rarely seen rooms so scrupulously kept.”7↤ 7. J.C. Whitebrook, “Jackson of the Red House, Hackney,” Notes and Queries 153 (31 Aug. 1927): 121. The catalogue of the contents of his house listed eight thousand books and three hundred oil paintings, but The Times said the collection was “mostly rubbish.”8↤ 8. Quoted by Whitebrook 121.

Jackson was a pious and prolific and grammatically bewildered author, but in the works I have seen he gives little information about himself. However, many surprising claims are made on his behalf in works by others, and some of these claims are quite intriguing. Indeed, many of the claims made on Jackson’s behalf are so marvelous that some subsequent critics have flatly disbelieved them, and most others simply ignored them.

Jackson as Inspiration and Patron of Walter Pater

Perhaps the most marvelous of these claims was the one made by Thomas Wright in a biography of Walter Pater published in 1907, thirteen years after the death of Pater. According to Wright, “In the Spring of 1877 . . . Pater was introduced to a handsome and studious young scholar named Richard C. Jackson,”9↤ 9. Thomas Wright, The Life of Walter Pater (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons; London: Everett & Co., 1907) II: 19. who was then twenty-six years old. At the time of their meeting, Jackson was already what Thomas Wright described as “an authority on Dante and Greek art, a Platonist, a Monk, a Re-Unionist—and more other things than he could for the moment recall.”10↤ 10. Wright (1907) II:20; “Jackson [at] twenty-six, was an authority on poetry, sculpture, painting, and music” (p. 21). Notice that Wright says Jackson was an authority on “more other things than he could for the moment recall”! Plainly the information about the relationship between Jackson and Pater comes entirely from Richard C. Jackson.

According to Wright, or rather to Jackson, Pater was dazzled by the young man:

“I am dumfounded!” exclaimed Pater excitedly. “I will write a book about you.” He did. That book was Marius the Epicurean—and Mr. Jackson was Marius.begin page 93 | ↑ back to top Pater said to Jackson, ↤ 11. Wright (1907) II:21-22.

“all that I have gleaned from thee [shall] swell thy fame to kiss posterity therewith. . . . I am glad to write about you, for, owing to you, my life has been enriched—its minstrelsy swelled.”

The remark led Mr. Jackson to compose on the spot some . . . stanzas, the last of which [begins]:

You greet me as your Marius! me

Who swelled for you life’s ministrelsy . . . .11

Wright says that these “metrical effusions” were “hidden away” for “twenty years or so . . . and Mr. Jackson discovered them . . . only a few days ago,” that is, about 1906.12↤ 12. Wright (1907) II:22.

Wright reports that Pater spent much of his leisure with Jackson, especially in the recently created St. Austin’s Priory in Walworth, which was extravagantly high-church. It was, according to Jackson, “a ‘Monkery’ of rich men,” and when he was wearing his monkish robes he called himself “Brother à Becket.” According to Wright, “the St. Austin brethren prepared young men for Holy Orders—Mr. Jackson taking Church History.” Jackson painted the interior of St. Austin’s church with illuminations, “with the result that within a few weeks St. Austin’s presented perhaps the most beautiful interior in London.” Mr. Dawkes, the connoisseur who provided the paint, said “that he had never seen anything so beautiful in his life.”13↤ 13. Wright (1907) II:32, 34. Pater called Jackson “the Archbishop,” and Jackson “styled himself ‘Richard Archprelate of the O.C.R.’” (Peter F. Anson, The Call of the Cloister, 2nd ed. [London: S.P.C.K., 1964] 100). Jackson gave the impression that he had a doctorate, probably in divinity—his 1923 catalogue calls him “Dr. Jackson” (#293)—and he said that the poems in his Golden City (1883) were written “at odd times which occurred between a special course of Divinity Lectures delivered in the Long Vacation of 1881 at Keble College, Oxford,” but there is no record of him among the degree recipients at Oxford and Cambridge. St. Austin’s Priory, which flourished in the 1870s and 1880s, was founded by a wealthy Anglican priest named George Nugée who bought several large houses in New Kent Road, Walworth, to house the brothers, and built an elaborate chapel, which disappeared long ago. Nugée’s sermons and the brothers’ public processions in Holy Week created a sensation in the neighborhood (Anson 95). Nugée and his followers were eager for a reunion of the Church of England with the Church of Rome; they imported Roman practices into their services, and, when these were discouraged by the Church of England, most of them joined the Church of Rome.

In his biography of Pater, Wright says that St. Austin’s Priory, Walworth, and Jackson’s house at Grosvenor Park, Camberwell, ↤ 14. Wright (1907) II:42, 45. Wright also says (II:80): “Marius the Epicurean . . . is the history of the progress less of a man than of a mind—the mind to a considerable extent of his friend, Richard C. Jackson . . . [though] few of the incidents in Marius’s career occurred to Mr. Jackson.”

which also had its chapel, became second homes to Pater, and he spent far more of his time in the company of Mr. Jackson than in that of any other friend. . . . Memories of both this chapel and St. Austin’s were drawn upon by Pater when he was writing the latter portion of Marius . . . . [Pater’s books called] Marius the Epicurean, Greek Studies, and Appreciations, all . . . were inspired by Mr. Jackson and Mr. Jackson’s books and pictures . . . .14and indeed Pater often wrote his essays in Jackson’s house.

Plainly, according to Wright’s account, or rather to what seems to be Jackson’s account as given to Thomas Wright, Richard C. Jackson was a major influence upon Walter Pater.

It is true that the allegations of influence here appear under the name of Thomas Wright rather than under that of Richard C. Jackson. However, there can be no doubt that Jackson endorsed and was responsible for the principal claim that he was the original of Pater’s most important book Marius the Epicurean, a work which W.B. Yeats called “the only great prose in modern English.”15↤ 15. W.B. Yeats, Autobiographies (London: Macmillan 1926) 373 (quoted in Pater, Marius the Epicurean [London: Dent; New York: Dutton, 1963] xiii). When Wright’s biography of Pater was published in 1907, Jackson wrote to The Academy signing himself “Marius the Epicurean” and saying that he was Pater’s “almost life-long friend.” And to make absolutely unmistakable the connection between the author signing himself “Marius the Epicurean” and Richard C. Jackson, the author identified himself with the portraits of Jackson which appear in Wright’s biography of Pater.16↤ 16. Marius the Epicurean, “The Wright Form of Biography,” Academy No. 1826 (4 May 1907). In a letter of 17 June 1913 to Mr. Palmer (Victoria and Albert Museum Archives), Richard C. Jackson refers to Wright’s claim that Jackson is “the Original of ‘Marius the Epicurean’—the ‘Sensations’ and ‘Ideas’ having come from the life of him who pens this paper.”

There are a number of difficulties with these claims. For one thing, though Pater said (according to Wright/Jackson) that Marius the Epicurean was written to “swell thy fame to kiss posterity therewith,” there is no explicit reference to Jackson in the book. This is a curious mode of swelling Jackson’s fame.

For another, there is no reference by name to Richard C. Jackson in any of Pater’s other writings either.17↤ 17. Samuel Wright, An Informative Index to the Writings of Walter Pater (West Cornwall, Connecticut: Locust Hill Press, 1987).

For another, Pater’s friendship with Jackson “seems to have been quite unknown until Wright published his biography of Pater in 1907.”18↤ 18. Anon., “An Eccentric Recluse: Mr. Jackson and Walter Pater,” Times, 30 July 1923: 8. “Those who knew Jackson, particularly in later years, were aware that he was inaccurate in matter’s of fact, believing just what he wanted to believe, and that his literary vanity was prodigious.”

begin page 94 | ↑ back to topFor another, the alleged friendship which Jackson said was “almost life-long” lasted by his own account only seventeen years.

Jackson himself said that he had “a stout volume” of letters and poems to Pater,19↤ 19. Marius the Epicurean, “The Wright Form of Biography,” Academy No. 1826 (4 May 1907). and he offered some autograph letters of Cardinal Newman and Walter Pater to the Victoria and Albert Museum,20↤ 20. According to a letter to me of 25 Nov. 1998 from Christopher L. Marsden, Assistant Museum Archivist, Victoria and Albert Archive and Registry, to whom I am much indebted for assistance and kindness. In a letter of 5 Aug. 1914 (V&A Archives), Jackson proposes to give the V&A “a very important book by my one-time friend Cardinal Newman—over which we had many a discussion with our friend Pater, which work contains the Autograph of Walter Pater. I purpose enriching this with letters of the Cardinal & Pater.” but no record of these valuable documents is known beyond Richard C. Jackson’s claims. He certainly never gave the letters of Cardinal Newman and Walter Pater to the Victoria and Albert.

One of the curious features of Jackson’s character is the pride he takes in his own modesty. For instance, he wrote in a letter of 1913: “No man, although I may say so, has done so much for the cause of Education as myself—in these days—and all witht any self-advertisement.”21↤ 21. Letter of 17 June 1913 (V&A Archives). The aggressiveness of his self-effacement is wonderful.

These difficulties have caused most writers on Walter Pater simply to ignore the claims made on behalf of Richard C. Jackson. And those who paid attention to the claims were frankly incredulous. Germain d’Hangest concluded in 1961 that Jackson is a “bizarre halluciné, sorti tout droit des romans de Huysmans.... son témoignage est aussi profondément suspect à nos yeux.”22↤ 22. Germain d’Hangest, Walter Pater: L’Homme et L’Oeuvre (Paris: Didier, 1961) I:286-87; Jackson was a “bizarre hallucinator who came straight out of the novels of Huysmans. . . . his witness is equally profoundly suspect in our eyes.” And Gerald Cornelius Monsman echoed her in 1977: “The ascertainable facts suggest . . . that the friendship [of Jackson and Pater] was a fantasy of Jackson’s pathological imagination.”23↤ 23. Gerald Cornelius Monsman, Walter Pater (Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1977) 46.

I do not endorse these conclusions, but I record them as part of a chain of marvels.

Charles Lamb and the Jacksons

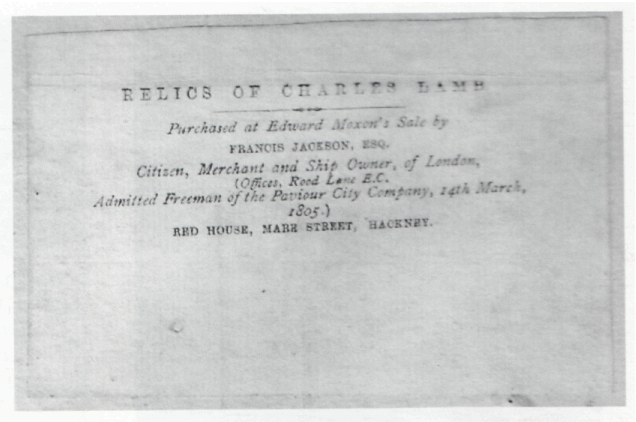

Wright learned from Jackson that Jackson’s paternal grandfather, Captain Francis Jackson, was a personal friend of Charles Lamb. Indeed, according to R.C. Jackson and Thomas Wright, Lamb’s essay called “Captain Jackson” in the Essays of Elia is a portrait of R.C. Jackson’s grandfather. Captain Jackson admired Lamb so much that, according to Jackson/Wright, “He named his son, Charles, after Lamb, and the present Mr. Jackson has Charles for one of his names.”24↤ 24. Wright (1907) II:19; “See T.P.’s Weekly and the South London Observer for 1905.” According to the dedication to Jackson’s The Risen Life (1889), his parents were Susanah and Richard Charles Jackson of Preston, County Lancashire. Francis Jackson obtained so many of Charles Lamb’s books that he commissioned a special bookplate to paste into them (illus. 3): ↤ 25. Copies are in my Gay’s Fables (London: J. Buckland et al., 1788), and in the Harvard copy of Burns’s Works (1802), the latter accompanied by the bookplate of Richard C. Jackson (Carl H. Woodring, “Charles Lamb in the Harvard Library,” Harvard Library Bulletin 10 [1956]).

RELICS OF CHARLES LAMB | - | Purchased at Edward Moxon’s Sale by [FRANCIS JACKSON ESQ.] Citizen, Merchant and Ship Owner, of London, | (Offices, Rood Lane E.C. | Admitted Freeman of the Paviour City Company, 14th March, | 1805.) | RED HOUSE, MARE STREET, HACKNEY25

Francis Jackson’s grandson R.C. Jackson also owned a surprising amount of the furnishings of Charles Lamb’s house: prints, a bookcase, two chairs, a bureau, a card table, a tea-caddy, scores of books, and Mary Lamb’s tea table.26↤ 26. Important Sale of Antique Furniture, Etc., 185 Camberwell Grove, Denmark Hill, S.E. By Order of the Executor of R.C. Jackson, Deceased: Catalogue of The Valuable Contents Being The Appointments of Seven Reception Rooms . . . An Extensive Library of Books Classical and Theological (about 8,000 vols.), 300 Important Oil Pictures [including] . . . Rubens, Canaletto, . . . Murillo, Corot, Bronzino, Breughel, Guido . . . Stubbs, . . . Claude Lorraine, . . . Vandyke, . . . Titian . . . Water Colour Drawings after Reynolds, Cruikshank, . . . Michael Angelo, and Others . . . Goddard & Smith Will Sell by Auction, at the Residence (23-25 July 1923), #137, 157-58, 506, 509-10, 512-13, 516, 523, 920-25 (116 books), 475. When these were sold after R.C. Jackson’s death, the catalogue entries for several of them bore a notation with some variant of “formerly belonging to Charles Lamb; purchased at the Moxon Sale, 1805.”27↤ 27. Goddard & Smith sale (1923), #157-58, 506.

These mementoes of Charles Lamb were clearly very important to R.C. Jackson, and he said that they were also important to Walter Pater. According to Jackson/Wright, ↤ 28. Wright (1907) II:151. Lamb’s clock does not appear in the Goddard & Smith catalogue.

[Pater’s] essay on Lamb was the outcome of the study of Lamb’s library, which . . . was in the possession of Mr. Richard C. Jackson, and of conversations with Mr. Jackson. . . . It was Pater’s first intention to commence his essay by giving an account of the friendship between Mr. Jackson’s grandfather and Charles Lamb, and a description of the library; but . . . the idea was abandoned. He cross-examined Mr. Jackson . . . in reference to Lamb’s life and habits, and much of the essay was written in the Charles Lamb room in Mr. Jackson’s house, with Lamb’s chair, bookcase, bureau, clock, and other treasures within touch.28begin page 95 | ↑ back to top

Perhaps this version of Pater’s essay on Lamb was “abandoned” after Pater “cross-examined Mr. Jackson” about his connection with Charles Lamb and found Jackson’s account difficult to credit. For one thing, the “Captain Jackson” of Charles Lamb’s essay is a half-pay naval officer, not the owner of a merchant ship as Francis Jackson was, according to his bookplate.

For another, Lamb said that his “dear old friend” Captain Jackson “was a retired half-pay [naval] officer, with a wife and two grown-up daughters, whom he maintained with the port and notions of gentlewomen upon that slender professional allowance.” Lamb’s essay mentions no son, and it is difficult to account for the descent of a grandson named Jackson from a Jackson who had no son.

For another, Lamb’s Captain Jackson lived in cheerful, genteel poverty, acting as if his ironware were made of silver, whereas Francis Jackson was prosperous enough to own a ship and to buy a good deal of furniture and books which he believed had belonged to Charles Lamb and pass them on to his grandson.29↤ 29. Wright (1907) II:19n3 says lamely that Francis Jackson “was not poor, as Lamb humorously represented him, nor had he any daughters—though he had two sisters.”

For another, R.C. Jackson told Thomas Wright that his grandfather had been a schoolmate of Charles Lamb at Christ’s Hospital, Lamb and Coleridge being admitted on 17 July 1782 and [Francis] Jackson on 12 May 1790,30↤ 30. Wright (1907) II:271 calls these three plus Leigh Hunt “The Lamb Quartette,” a phrase which might have surprised Charles Lamb. but Francis Jackson was born about 1784,31↤ 31. Assuming that Francis Jackson was the normal age of about twenty-one when, as he says in his bookplate, he was made a Freeman of the Company of Paviours in 1805, he was born in 1784. two years after Lamb was admitted to Christ’s Hospital.

It is very difficult to believe that Lamb’s Captain Jackson has anything to do with Francis Jackson who was the grandfather of R.C. Jackson.

Both in Francis Jackson’s bookplate and in the catalogue of Richard C. Jackson’s sale in 1923, works associated with Charles Lamb are said to have come from “Moxon.” This is inherently plausible, for Edward Moxon was Charles Lamb’s publisher and his intimate friend, and when he died in 1834 Lamb left him his books. Large numbers of Lamb’s scruffy books are known to have gone through the hands of Edward Moxon.

The catalogue of Richard C. Jackson’s estate also says that some of his Lamb acquisitions were “purchased at the Moxon Sale, 1805”. This date seems somewhat implausible, for in 1805 Edward Moxon was only four years old!

The mistaken date of the “Moxon Sale, 1805” may derive from Francis Jackson’s bookplate, in which the words “Moxon’s Sale” and “1805” both appear. A careless reading could lead to the conclusion that “Moxon’s Sale” was on “14th March, 1805.” However, the grammar is quite plain: what happened on “14th March, 1805” was that Francis Jackson was “Admitted Freeman of the Paviour City Company.”

Whether or not this so-called “Moxon Sale” is attributed to 1805 or to some date more plausibly after Charles Lamb’s death in 1834, the most curious feature of it is that there seems to be no reference to a “Moxon Sale” except in the context of Francis and Richard C. Jackson. Edward Moxon is known to have sold books from Charles Lamb’s library, but he is not known to have had a sale.32↤ 32. Crabb Robinson wrote in his Diary for 27 April 1848: “Moxon . . . has really sold Lamb’s books to some American. . . . M: told me at first that he would give the books to the Univ: Coll: [London] but afterwds said they were not worth accepting” (MS in Dr. Williams’ Library).

A number of the books went from Lamb via Moxon, Francis Jackson, and Richard C. Jackson’s sale to Harvard, where they were examined carefully by Carl Woodring for his account of “Charles Lamb in the Harvard Library.” Woodring’s conclusion is succinct. The books in Harvard which were attributed to Lamb in the 1923 Jackson catalogue “bear no marks from Lamb’s hand . . . [and] it must be doubted whether Lamb owned any of them.”33↤ 33. Carl H. Woodring, “Charles Lamb in the Harvard Library,” Harvard Library Bulletin 10 (1956): 379. When I wrote to Mr. Woodring, he replied to me on 1 Jan. 1971 that he had nothing to add to this conclusion.

The connection of Francis Jackson and Richard C. Jackson with Charles Lamb, his books and furniture, is, then, exceedingly tenuous. They may have owned books and pictures and bureaux of Charles Lamb, but there seems to be no evidence to confirm these bare assertions.

The Jackson Collection Sold in 1923

According to Thomas Wright, ↤ 34. Wright (1907) II:81, 229.

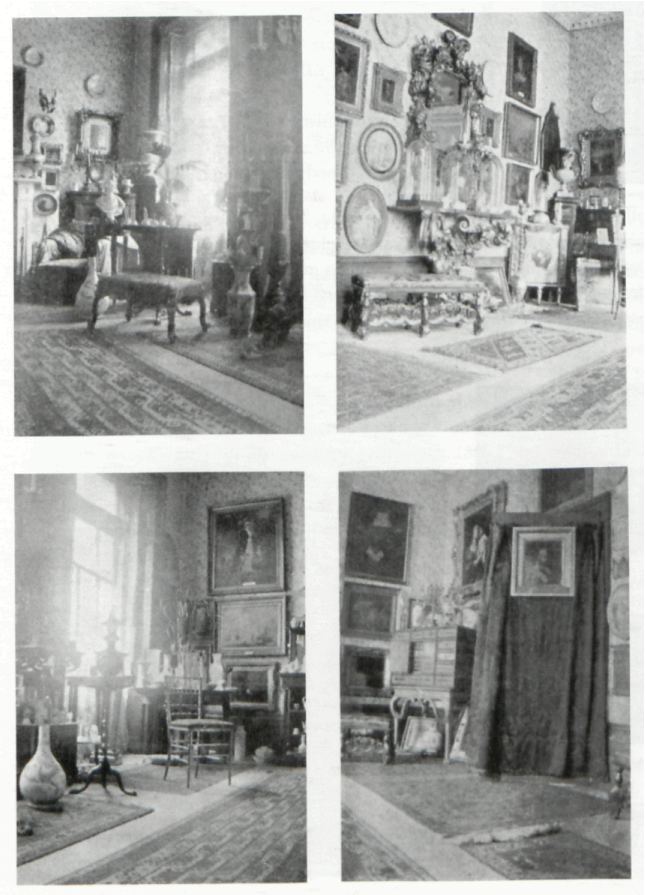

Mr. Jackson possessed, and still possesses, one of the most valuable private libraries in England . . . . Marius the Epicurean—Mr. Richard C. Jackson—still resides at Camberwell, and in a house that can only be described as a literary and artistic Aladdin’s Palace. We suppose so many works of art, valuable books and objects that have belonged to men of genius could scarcely be found anywhere else in the same amount of space . . . .34

Wright gave surprising substance to his claims by reproducing photographs of Jackson’s eclectically over-furnished rooms, which show what Wright calls Thomas “Carlyle’s writing-table and chair,” another chair “from the Palace of Michaelangelo,” and bronzes which were “Napoleon the Third’s”35↤ 35. Wright (1907) II:181, 185, 189. In Jackson’s 1923 sale, “CARLYLE’S EDINBURGH UNIVERSITY CHAIR” and “THOMAS CARLYLE’S WRITING TABLE . . . old Chippendale” were #466, 470, “A cardinal’s Chair . . . (Purchased by Dr. Jackson at Michael Angelo’s Palace, in Florence)” was #579, but the only Napoleon III item was “A very Handsome Gilt Ormolu French Clock . . . Stated to have been presented by Napoleon III. to Isabella, Queen of Spain” (#21a). Carlyle’s writing desk was offered in Oscar Wilde’s sale by Mr. Bullock of 24 April 1895. (illus. 4 and 5). Of course the photographs re begin page 96 | ↑ back to top produce the objects rather than the associations which make the objects interesting, and what Wright calls “bronzes” seem to be porcelain. But plainly Jackson thought he owned furnishings associated with other notable figures besides Walter Pater and Charles Lamb.

The sale catalogue of the contents of Jackson’s house lists a surprising number of pieces of what may be called Association Furnishings. These include “A chalice, on stem, part gilt, Elizabethan, said to have belonged to [the Jesuit Martyr Edmund] Campion,” executed in 1581 and beatified in 1886 (#1100); “A vellum Portfolio Album, formerly belonging to, and with autograph letter from Charles Dickens”36↤ 36. No Richard Jackson is in the indices of The Letters of Charles Dickens, ed. various, 10 vols. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1965-1998). (#966) plus a marble bust of Dickens by Angus Fletcher (#559); a portrait by Sir Joshua Reynolds of the Prince of Wales presented by the Prince’s mistress Perdita to Thomas Gainsborough and by him to the father of R.C. Jackson (#176); a tortoiseshell boudoir-clock and a satinwood table which had belonged to David Garrick (#556, 571), the second of which had also belonged to Dante Gabriel Rossetti;37↤ 37. Lot #552 is “Two sand glasses (relics from Benjamin Webster and David Garrick Sale).” “George Brinsley Sheridan,” who is said to have owned a Heppelwhite table (#552), may be intended for the dramatist Richard Brinsley Sheridan. two Sheraton armchairs from Dr. Johnson’s drawing room (#538-39); “A melon-shaped tea pot . . . reputed to have belonged to Marie Antoinette” (#1092); and an oval satinwood table “FORMERLY THE PROPERTY OF THE POET SCHILLER” (#464).

In none of these cases is there any indication of by whom the work is said or reputed to have belonged to such a notable person. However, the provenance of the portrait of the Prince of Wales is said to derive “from description at the back” [of the frame]. This description surely implies that it has the authority of both Francis Jackson, to whom Thomas Gainsborough is said to have given the picture, and of Richard C. Jackson, who inherited it.

The chronology of the provenance of the Reynolds portrait is somewhat implausible. Thomas Gainsborough, who died in 1788, cannot have given the picture to Jackson’s father, who was born in 1810, and he is exceedingly unlikely to have given it to Jackson’s grandfather, who was “Admitted Freeman of the Paviour City Company, 14th March, 1805” and was only about four years old at the time of Gainsborough’s death. It is virtually inconceivable that R.C. Jackson’s father or grandfather obtained the painting directly from Thomas Gainsborough.

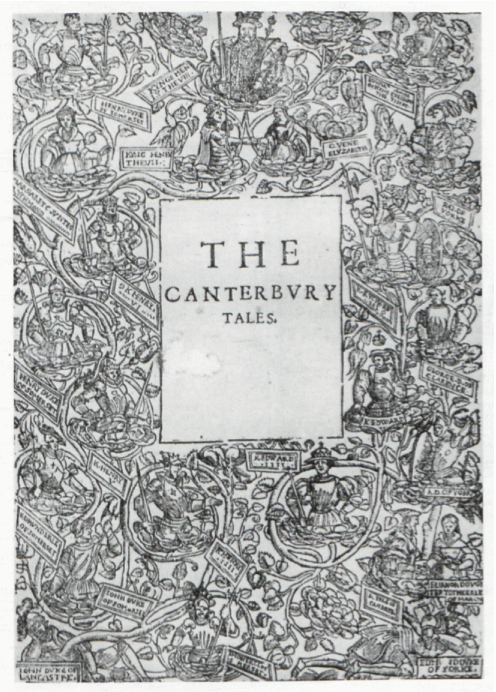

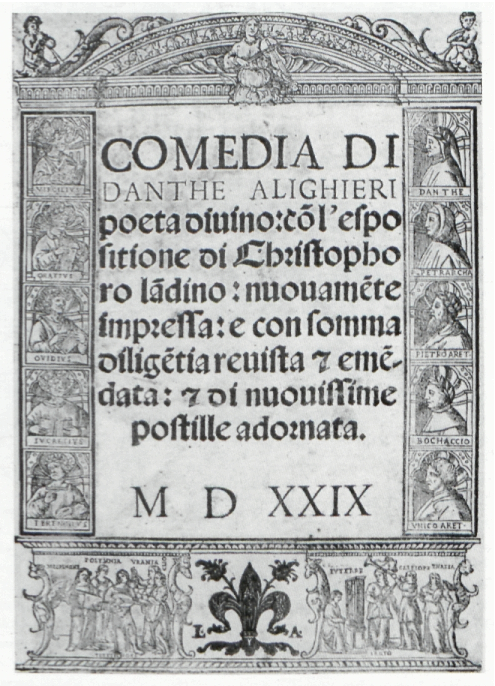

Wright also reproduced photographs of some notable books from Jackson’s library: The Workes of our Antient and learned English Poet, Geoffrey Chaucer (1598) (illus. 6), Dante’s Divine Comedy (Venice, 1529) (illus. 7), Sebastian Brandt’s edition of Virgil (1502), Homer (Venice, 1525) (illus. 8), and [John] Guillim, Display of Heraldry, Fourth Edition (1660) with “every coat [of arms] . . . properly coloured by hand at the time of publication.”38↤ 38. Wright (1907) II:237, 241,245, 248, 251, 255, 258, 261, 268, 269, 273, 276. Only “Public [sic] Vergilii Maronis Opera” (1502), #675, appears in Jackson’s 1923 sale. These are works of substantial intrinsic importance, and, presuming that Jackson really did own them, they indicate that some of Jackson’s possessions were quite interesting.

Wright says that Pater was especially interested in Jackson’s “early edition of Caxton and a pre-Caxtonian copy of the Golden Legend, with beautiful binding and clasps.”39↤ 39. Wright (1907) II:174. These are important works, though Wright does not reproduce them. But our persistent suspicion of the accuracy of Wright and Jackson may be allayed by reference to Jackson’s 1923 catalogue, which listed works which must have existed, however imprecisely they were described. The 1923 catalogue lists many 15th- and 16th-century books, including Caxton’s Game and Playe of the Chesse, Prologues (Nuremberg, 1482), a volume by Joannes Gerson (1489), “Instit Imperia” (1499), “Albert Durer’s Designs of the Prayer Books, . . . and Biblia Pauperum, by John Wiclif,” 15th-century copies of the Psalter, Northern Book of Psalms, and a Prayer Book, plus thirty-seven unnamed volumes of “Old classical works, 15th and 16th century.”40↤ 40. 1923 Jackson catalogue #767, 872, 719, 488, 947, 967, 874-75. I do not find the Golden Legend. This must have been a genuinely notable library, though the treasure islands were lapped by a vast, anonymous sea. After “The Lady of the Lake, manuscript copy by Walter Scott” (#1032) is an enormous series of 1350 volumes described merely as “Books, various” (#1064-90).

The catalogue of Jackson’s library is deliciously or infuriatingly erratic, with references to the Spanish monarch “Phillipi of Spain” (#194), to a volume of “Drayto’s piems” (#671), and to those famous Romans “Public Vergilii” (#675) and “Mere Antonio” (#16). I like to think of a triumvirate consisting of Marc Antony (Antonio Maximus), Marc Antonio Raimondi (Antonio Minimus), followed by Mere Antonio.

The catalogue records a wonderful combination of trash and treasures, from “A FINE OLD PERSIAN CORRIDOR RUG (14-ft. 6-in. by 5-ft. 9-in.)” (#428) to “a silk chasuble with gold braid bordering” (#583) to a collection of ninety unset emeralds (#1221) to “A brown paper parcel containing sundry prints and drawings and sketches” (#26).

The most spectacular entries are the paintings and drawings, including works by Michael Angelo, Canaletto, begin page 97 | ↑ back to top

Of course, attributions are cheap, collectors are vain, and dealers are hopeful. Anyone can say, “Here is a Michael Angelo drawing,” “Gerard David painted this picture,” “The Prince of Wales sat for Sir Joshua Reynolds for this portrait.” For instance, two very large paintings are described as Rubens portraits of the Archduke Albert and his wife Isabella. But their authenticity was confirmed when they were given to the National Gallery under the terms of Jackson’s will41↤ 41. “I bequeath to the National Gallery London my two portraits by Rubens” (Will of Richard Charles Jackson “died 25/4/23 Inglewood N.H. Grove Park Denmark Hill S4 . . . Effects £4673-19s6d,” a copy of which was generously sent to me by Mr. Kevin Hebborn). I cannot explain why these works bequeathed to the National Gallery appeared in the auction of Jackson’s effects, unless it was for the purpose of obtaining an evaluation. Jackson also bequeathed “to the South Kensington Museum [now the Victoria and Albert Museum] London all my ornamental antique silver and silver plated articles,” and the museum accepted about 80 pieces, chiefly 18th-century English domestic silver, plus a Siennese chalice, and an Augsburg ciborium (c. 1700), according to a letter to me of 25 Nov. 1998 from Christopher L. Marsden, Assistant Museum Archivist of the V&A. (Jackson also offered the museum sword mounts and a dagger which never materialized.) Jackson’s remaining silver was in the 1923 sale, 47 lots of antique silver and 15 lots of silver plate. and exhibited as genuine Rubens paintings. In the way of artistic fashion, they have now been recatalogued as paintings from Rubens’s workshop,42↤ 42. Gregory Martin, National Gallery Catalogues: The Flemish School 1600-1900 (London, 1970) #3818-19; “There is no reason to suppose” that they are not “work[s] of the seventeenth century.” The provenance notes: “Coll. Richard J. [sic] Jackson, Camberwell, by 1900; for sale by private contract, Sotheby’s, 1912, not sold; bequeathed by Richard J. Jackson, 1923,” with no reference to Jackson’s 1923 sale catalogue. but they are still in the National Gallery.

Regardless of the name attached to them, the portraits of the Archduke Albert and the Infanta of Spain are very fine paintings. It seems likely that other paintings in Jackson’s house were also fine and valuable works. There must have been many treasures among the rubbish in Jackson’s “literary and artistic Aladdin’s Palace.”

Richard C. Jackson’s Blake Collection

What interests me most about Jackson is his enthusiasm for William Blake. Jackson was President of the William Blake Society of Arts and Letters, he wrote letters to the press about Blake, his Blake Society published works by Blake,43↤ 43. William Blake, The Book of Thel [Illustrated by] W.R. Kean (Lambeth: Printed as Manuscript [sic] for the Blake Society, [?1917]) and William Blake, Little Tom the Sailor (London, 1917). he said he owned important works by Blake, and he collected a number of works which he thought had belonged to Blake. None of these works associated with Blake was recorded before Jackson acquired them, and, with one curious exception, none of them has been recorded since that time either.

In a letter of 1901 Jackson said: “I have lived with William Blake (in the Spirit) for over 20 years,”44↤ 44. Quoted from a letter to Henry Syer Cuming (1817-1902), founder of the local museum in Southwark; a reproduction of the letter in Southwark Local Studies Library was generously sent to me by Mr. Stephen Humphrey, archivist in the library. The letter continues: “I appear to know as much as that[?] of his nature, knowing also how sensitive he was of the slightest act done towards himself, that I sincerely trust you will let me thank you for your kindness towards to [sic] him.” Some of Jackson’s claims seem to be as strange as his diction. that is, since before 1881 when he was thirty. He said that “my father . . .knew Blake personally”45↤ 45. Jackson to Palmer, 17 June 1913 (V&A Archives). and had seen Blake’s now-lost picture of “The Last Judgment” “in the artist’s ‘Salon’ in Fountain Court, in the Strand,” where Blake lived in 1820-27,46↤ 46. R.C. Jackson, “William Blake at the Tate Gallery, Resident in Lambeth from 1793-1800,” South London Press, 31 Oct. 1913; “My father said Frederick Tatham had it in his house in Lisson Grove, in 1846 or 1847.” He also said of “The Deluge,” a study of the sea: “Blake exhibited it to my father, saying it was a sketch he made on the seashore on a rough day at Felpham, Bognor.” and “many of his relics are here which my father acquired of Mrs Blake & Tatham—and here are his Clock and watch & chain & seal—Still going & keeping fairly good time.”47↤ 47. Jackson to G.H. Palmer of the V&A, 14 June 1913 (V&A Archives). In a letter of 5 Aug. 1914, Jackson said: “on the 12th Inst I am arranging a little local Exhibition of some of my Blakean treasures, at the Central library at Camberwell,” but in a letter of 8 Aug. 1914 he said he had cancelled the exhibition because of the terrible times (V&A Archives). These Blake memorabilia do not appear in his sale catalogue, and no other reference to them is known. In a copy of Songs of Innocence and Experience with Other Poems By W. Blake (London: Basil Montagu Pickering, 1866) in the collection of Robert N. Essick, Richard C. Jackson put his bookplate and wrote: “such was my father’s disgust at Gilchrist’s Journalistic Performance, that he would not allow him to use any of his Blakean material.” Blake appears to be wearing a seal under his left elbow in the Phillips portrait of Blake engraved by Schiavonetti for Blair’s Grave, a copy of which Jackson gave to the Victoria and Albert Museum Library.

Jackson wrote many newspaper articles on Blake, and indeed “I have long had a book on the stocks, over 20 years, about Blake.” With characteristic self-effacement, he wrote: ↤ 48. Letters of 14 and 17 June 1913 (V&A Archive).

My Blake (my opus on Blake) will contain the last word on any subject connected with our poet-painter and prophet—upon which I have been engaged over twenty years, by the aid of my father who knew Blake personally. The work will contain some splendid little items full of the utmost interest & entirely unknown. . . .

I want my book to contain all my fire & spirit and I fear publishers will want this so watered down so as to become like those vapid things which are so deplorable. Blake was begin page 102 | ↑ back to top one of our very greatest heroes—of which the world knows nothing.48

What a pity such a valuable work was never published! A work written with “all my fire & spirit” and with reproductions from his own collection might have proved very interesting. But it is difficult to believe that Jackson’s opus on Blake had any existence outside Jackson’s fertile and apparently self-delusive imagination.

Jackson said that his father, who “was born in 1810, . . . was associated with a large number of earnest young men . . . gathering round the feet” of Blake. “My respected father detailed to myself many particulars respecting the mode of life and deep spiritual character” of Blake.49↤ 49. “William Blake: An Unlooked for Discovery,” South London Observer, 22, 29? June 1912. His respected father must have been very young when he knew Blake, for he was only seventeen when Blake died in 1827.

Jackson said that when he was “quite a boy” (c. 1860?), his father took him to tea in the house in Hercules Buildings, Lambeth, which the Blakes had occupied from 1790 to 1800. There Jackson saw Blake’s fig tree and “the luxurious vine . . . nestling round the open casement,” and his father told him that the vine and fig tree were presents to Blake from George Romney, the vine having been “grafted from the great vine at Versailles or Fontainbleau.”50↤ 50. “William Blake: An Unlooked for Discovery,” South London Observer, 22 June 1912.

George Romney is known to have admired Blake, and Hercules Buildings did have a grapevine, but no one else records that the vine and fig tree were given to the Blakes by George Romney. Even if the information of Jackson’s father is correct, it is still very indirect, for Jackson’s father was not born until eight years after Romney died and ten years after the Blakes left Lambeth.

But we have only Jackson’s word for the association of his father with Blake’s disciples.

The Blake drawings which R.C. Jackson owned are portrait busts of Dante (12″ × 9″) and of Chaucer (16″ × 13″) (#182), “a fine pen and ink drawing with inscription and figure cartoon” (#245), and “Blake’s original oil-colour sketch for Chaucer,”51↤ 51. Wright (1907) II:180. none of which appears in Martin Butlin’s magisterial catalogue raisonné of The Paintings and Drawings of William Blake (1981).

The engravings are the largest ones Blake made, for Chaucer’s Canterbury Pilgrims and for Hogarth’s Beggar’s Opera,52↤ 52. #293, not attributed to Blake in the 1923 catalogue. plus “Blake’s own copy” of the Illustrations of the Book of Job “which is over 20 inches high by 16 wide,”53↤ 53. “William Blake at the Tate Gallery, Resident in Lambeth from 1793-1800,” South London Press, 31 Oct. 1913; “Blake’s own copy” of Job is not otherwise known, it did not appear in Jackson’s sale, and the size is enormous; the largest known copy is c. 17 × 13 ¼”. and there is an otherwise unknown manuscript letter from William Blake to John Flaxman (#293). Jackson’s catalogue listed “The Library of William Blake, 25 vols.” (#812), with no further detail of author, title, size, or subject. None of these copies is known to Blake scholarship.

Even more unusual are furnishings from Blake’s house: an anonymous drawing of a “Female in Cerise Robe in Saintly Attitude with Skull on Lap (9-in. by 8-in.), formerly in the collection of William Blake, and a ditto, The Holy Family (16-in. by 11-in.)” (#276), a “Heppelwhite open arm mahogany chair with seat and back in velvet. FORMERLY THE PROPERTY OF WILLIAM BLAKE, THE POET” (#465), “WILLIAM BLAKE’S PAINTING TABLE, with leather centre, tilting top and on tripod (formerly Gainsborough’s) (20-in. by 15-in.)” (#579f), “cushions worked by his wife, his classical dinner service, some of his tea-set, and . . . his eight-day English clock, which still keeps good time.”54↤ 54. “William Blake, Hampstead, and John Linnell,” South London Observer, summer 1912. There is no other record of any of these furnishings outside the Jackson collection, and only the first three appeared in the Jackson sale. A velvet-backed chair and a classical dinner service sound most unlike the impoverished poet, however much one might expect them among Jackson’s Edwardian magnificence.

The elegant little tilt-topped painting table seems more appropriate for Blake, but its provenance from Gainsborough is very surprising. There is no known connection between Blake and Gainsborough, and Blake was only thirty-one when Gainsborough died. Of course the catalogue merely says that Gainsborough and Blake owned it, not that Blake obtained it from Gainsborough; Blake could have obtained it at any time after Gainsborough’s death in 1788.

This object has been traced today, and indeed when it was examined recently it proved to have a Blake drawing in the drawer. Unfortunately the drawing is not BY Blake; it is merely a representation OF him, the artist who portrayed Blake being a man who owned the table after 1923. There seems to be nothing in the table itself to associate it with either Gainsborough or Blake, and the claim in the 1923 catalogue must be judged at least in part by the plausibility of other claims which are made on behalf of Richard C. Jackson.

Perhaps the most surprising Blake works claimed in Jackson’s library are the very rare books there. In his catalogue was “The Book of Thel, by William Blake, 1789” (#737). A newspaper report of the Thirty-Fourth Meeting of the William Blake Society of Arts and Letters reports the “Interesting Speech of the President” Richard C. Jackson and gives an account of books displayed then, including “books with Blake’s Autograph,” the title pages of Blake’s America and Europe, plus a copy of Jerusalem, identified as begin page 103 | ↑ back to top “an original decorated copy.”55↤ 55. Anon., “Felpham and the Poet-Painter Blake. The Thirty-Fourth Meeting of the William Blake Society of Arts and Letters. Interesting Speech of the President,” Observer and West Sussex Record, 27 May 1914. The newspaper does not specify that Jackson owned these Blake works, but it implies that he did. And finally, Thomas Wright describes an occasion when Walter Pater and Jackson were talking in Jackson’s library: ↤ 56. Wright (1907) II:180. Jackson’s copy of “Blake’s original oil-colour sketch for Chaucer” is not recorded in Butlin’s Paintings and Drawings of William Blake (1981). Blake strongly disapproved of oils and very rarely used them. A copy of B.H. Malkin’s A Father’s Memoirs of His Child (1806) with a frontispiece designed by Blake and an encomium about him, bearing Jackson’s bookplate, is in the library of the University of Kentucky; it did not appear in Jackson’s 1923 sale.

The talk having glided to William Blake, a topic upon which the two friends held but one opinion, Mr. Jackson brought out his Blake treasures: an engraving of the Canterbury Pilgrims, Blake’s original oil-colour sketch for Chaucer, several copies of Blake’s works in proof state, including the plates to the Book of Job, Young’s Night Thoughts, and Blair’s Grave—all in uncut states, and a copy of the famous “Marriage of Heaven and Hell,” coloured in water-colours by Blake’s own hand.56

Jackson also says that “My Father had Blake’s M/S of this [Blake’s Descriptive Catalogue], and I may have it still.”57↤ 57. Letter of 5 Aug. 1914 (V&A Archives); the letter continues: “It is only last month that I re-discovered Michael Angelo’s M/S of Justinius[?] so I may find Blake’s M/S Cat also amongst my father’s books here.” No one else is known to have seen the manuscript of Blake’s Descriptive Catalogue since the book was published in 1809.

These Blake treasures identified by Wright are very remarkable. The Canterbury Pilgrims engraving we have seen in Jackson’s sale, but none of the others is named there. Some of the works are not rare in themselves, such as Blake’s Illustrations of the Book of Job (1826), Young’s Night Thoughts (1797), and Blair’s Grave (1808), but no copy of Night Thoughts is known “in proof state” like Jackson’s.

All the other Blake works which are claimed for Jackson’s collection are genuinely rare. The Book of Thel survives in sixteen known copies, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell in nine copies, separate pulls of the title pages of America and Europe in one to four copies, and Jerusalem in only one complete colored copy like the one shown when Jackson spoke to the Blake Society of Arts and Letters.

These works are immensely valuable today, beginning at about $20,000 per page,58↤ 58. This estimate should perhaps be revised to “$100,000 a page” in light of the sale of the 24 plates of The First Book of Urizen (E) at Sotheby’s (New York) in April 1999 for $2,500,000. and no known copy of Thel, The Marriage, America, Europe, and Jerusalem can be associated with Richard C. Jackson. Is there a wonderful trove of Blakes from the Jackson collection to be discovered somewhere in South London where he lived? Was Jackson mistaken in believing that he owned genuine Blakes? Is there fraud involved here?

Before we go further, let me reiterate that much of the evidence that Jackson owned important original Blakes is indirect. Many of the claims are made on his behalf rather than by him. One of those making the claims is an anonymous newspaper reporter, and another is a hurried auction-cataloguer who sometimes seems to have been as careless with his identifications as with his orthography.

The third person making the claim, however, is Thomas Wright, and Wright too was a Blake enthusiast, president of a Blake Society, and the author of The Life of William Blake (1929). Thomas Wright, at least, is likely to have recognized a genuine Blake when he saw one.

However, it is not clear that Wright saw Richard C. Jackson’s Blakes. The conversation between Walter Pater and Richard C. Jackson which Wright reports could only have been told him by Richard C. Jackson—or conceivably by someone who had it from Jackson. The authority for Jackson’s ownership of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell “coloured in water-colours by Blake’s own hand” and of proof copies of Blake’s Illustrations of the Book of Job, Blair’s Grave, and Young’s Night Thoughts must derive from Richard C. Jackson himself.

The paradox of Jackson’s ownership of an otherwise unrecorded copy of what the catalogue calls “The Book of Thel, by William Blake, 1789, in board cover, quarto size” may be explained fairly readily. The catalogue description continues: “39 copies, and 13 royal quarto ditto.” This is manifestly not the “1789” edition of The Book of Thel, of which only sixteen copies are known to survive. Those fifty-two copies of The Book of Thel in the 1923 Jackson sale must be from The Book of Thel, [Illustrated by] W.R. Kean (Lambeth: Printed as Manuscript [sic] for the Blake Society, [?1917]) of which Richard C. Jackson was president. This edition of The Book of Thel does not bear Blake’s designs, and no one who knew anything about Blake could have mistaken it for the first issue of 1789. The fault here is manifestly that of the 1923 cataloguer and not that of Richard C. Jackson.

Some of the other Blake works attributed to Jackson’s collection may be similarly explained away, though with rather more difficulty. John Camden Hotten published a color facsimile of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell in 1868, and William Muir had made facsimiles of Blake’s America and Europe in 1887. These facsimiles are sufficiently skillful to deceive an inexperienced eye, and the reporter for the Observer and West Sussex Record in 1914 may not have been very experienced in Blake matters.

There was no colored facsimile of Jerusalem until 1951. However, there was a plausible uncolored facsimile made in 1877, and in the Observer and West Sussex Record account, the words “decorated copy” may refer to marginal designs rather than to coloring.

begin page 104 | ↑ back to topThe copies of America, Europe, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, and Jerusalem said to have been in Jackson’s collection may then, by a generous allowance of courtesy and credulity, refer to facsimiles of these works rather than to genuine originals. The known histories of all known original copies of these works scarcely allows the possibility that any of them belonged to Richard C. Jackson. Certainly no book associated with William Blake is known to have one of Richard C. Jackson’s bookplates (illus. 9).

But what are we to make of the “books with Blake’s Autograph” which are said to have been with these other Blakes in Jackson’s collection?

No known book with Blake’s autograph can be traced to the collection of Richard C. Jackson, much less twenty-five books from “The Library of William Blake.” It is easy and perhaps gratifying to think that unmarked books in one’s own collection came from the library of William Blake or of Charles Lamb, but books with autographs of William Blake and Charles Lamb are a different matter. Such autographs in books are likely to be either genuine or forged.59↤ 59. There is a third possibility which must be considered. There are well over 20 London contemporaries of the poet bearing the names “William Blake” (see “A Collection of Prosaic William Blakes,” Notes and Queries [1965]: 172-78), and several of them put their names in books which have been traced. However, it seems extremely improbable that Richard C. Jackson or anyone else had a collection of “books with [the wrong William] Blake’s Autograph.” Wishful thinking is one thing, wishfully associating one’s books and furniture with Thomas Gainsborough or Edmund Campion or Charles Lamb or William Blake. Wishful forgery is quite a different matter. And however wishfully we may think that Richard C. Jackson associated his books and pictures and furniture with the illustrious, there is scarcely any evidence that he used forgery to authenticate his wishes.

In any case, neither originals nor facsimiles nor forgeries of America, Europe, Jerusalem, the manuscript of The Descriptive Catalogue, or The Marriage of Heaven and Hell appeared in the catalogue of Jackson’s collections. Nor did copies of the far more common Illustrations of the Book of Job, Young’s Night Thoughts, and Blair’s Grave appear there. Surely at least some of these works were in Jackson’s collection, whether originals or facsimiles. What can have become of them?

There is at least a possibility that they were disposed of before his death. Though the newspaper accounts reported with relish that Jackson refused to sell his treasures when his financial reverses reduced him to poverty—one obituary said that when he died he had only 5s in the bank60↤ 60. Anon., “Recluse’s £12,000 Art Hoard: Only 5s. in the Bank: Poverty in a House of Treasures: Rubens Pictures for the Nation,” [no periodical identified, ?July 1923]. According to Thomas Wright of Olney: An Autobiography (London: Herbert Jenkins Ltd, 1936) 125: “Having lost a large sum of money by the failure of the Australian banks, he was poor but would not part with any of his treasures. He had enough but hardly enough to live on . . . .” Wright also said that Jackson was “eccentric beyond belief” (p. 192). —he had made substantial donations to public institutions. In June 1900 he gave eight hundred and fifty books and pamphlets on Dante to Southwark Public Library,61↤ 61. Samuel Wright, “Richard Charles Jackson,” Antigonish Review 1 (Winter 1971): 88. I am told by Mr. Stephen Humphrey, Archivist, Local Studies Library, Southwark, that Jackson’s gift actually went to Newington Library, which became the central library for the Metropolitan Borough of Southwark, and that in the 1980s the collection was transferred to London University, probably University College. However, I am told by Ms. Susan Stead of University College Library that Jackson’s Dante collection did not come to them. he gave prints and books to the Victoria and Albert Library,62↤ 62. Letter to me from Christopher L. Marsden, Assistant Museum Archivist, V&A, 25 Nov. 1998. The books donated by Jackson consisted of a handful of twentieth-century volumes, including typographic editions of Blake’s Jerusalem (1904) and Milton (1907), both ed. E.R.D. Maclagen and A.G.B. Russell. (On 17 June 1913 Jackson asked G.W. Palmer to “let me know if you have copies of Blakes Milton & Jerusalem the originals[?] in your Library at Kensington, if not—I will see if I can present copies” [V&A Archive].) The illustrations which Jackson gave to the V&A are an etching by John A. Poulter of Blake’s cottage in Felpham and a portrait of Blake in a process reproduction of the engraving by Schiavonetti after T. Phillips. he bequeathed ornamental antique silver and silver plate to the Victoria and Albert Metalwork Department, and he bequeathed two fine oil paintings attributed to Rubens to the National Gallery. It would be charitable to hope that Jackson’s original decorated copies of William Blake’s America, Europe, Jerusalem, and The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, plus his uncut, proof copies of Illustrations of The Book of Job (Blake’s own copy), Blair’s Grave, and Young’s Night Thoughts may yet turn up in an unexpected public collection. After all, who would have expected an important collection of Dante to turn up in the Southwark Public Library?

Richard C. Jackson certainly had an eclectic collection of treasures, including two portraits from the studio of Rubens, dozens of incunabula, a 1525 Homer, a 1529 Dante, and a 1598 Chaucer. He also had an impressive collection of wishes, including intimate friendship with Walter Pater, extensive collections of books and furnishings which had belonged to Charles Lamb and William Blake, and books of the utmost rarity engraved by William Blake. Some of these wishes may have come true. One may at least hope that some of them did. It would be worth a good deal to know where that truth lies.

begin page 105 | ↑ back to top

Appendix

Works by R.C. Jackson (1847-4 April 1923)

63↤ 63. The year of Jackson’s birth derives from the General Record Office in

London (Vol. IV, p. 58, September 1847), kindly reported to me by Mrs. June Harris. Mrs. Harris tells me that

she inherited a silver fish slice of 1838 engraved with “T W / from / RJ C / 1906” which

was given to her grandfather Thomas Wright on an occasion when Jackson stayed with him.

*Works marked by an asterisk were seen as clippings (often without indication of date or journal) in the Ruthven Todd Collection of Leeds University.

1879 The Very Rev. Provost Nugée (1879) <Wright (1907)—see note 11>

1883 The Golden City: Sonnets and Other Poems Written at Keble College, Oxford, with a sonnet “In Memoriam” of Dr. E.B. Pusey (Oxford: B.H. Blackwell, 1883)

1883 The Risen Life: Hymns and Poems for the Christian Year—Easter to Advent (London: Masters & Co., 1883); New Edition, with Miniatures in Gold and Colours (London: J. Westall, 1886); Third Edition, illustrated by D.G. Rossetti, etc., 1889; (1894)

1883 Sunday Readings (Bristol & London, 1883)

1886 His Presence: Spiritual Hymns and Poems of the Blessed Sacrament of the Altar for Devotional Use at Holy Communion (London: J. Westall, 1886); Second Edition, with New Hymns (London: Church of England Text Society, 1887); Third Edition (London: R. Elkins[e] [1889]); His Presence: Impromptu Hymns and Poems at the Altar, Written in the Presence of the Holy Sacrament, Fourth Edition (London: R. Elkins & Co., 1891) <25,000 copies of the last three editions were sold at ls (Wright (1907) II:66)>

1886 Jackson’s Church of England Lectern and Parish Kalendar for 1886, 1887 (London, 1886); Second Edition (1889); (1892-93); (1897) <according to Wright (1907) II:230, “350,000 dozen” copies of the 1897 edition were sold>

1892 Anon., Divine Poems (1892) <Wright (1907)>

1896 Ye Purple Yeast [sic]: A Poem Written in Vindication of Old Englands Honour [in reply to William Watson’s poem The Purple East] (London: Bowyer Press, 1896) <the book is a satire (on William Watson’s Purple East) defending Britain’s non-interference policy in Turkey and the East; the Bodley copy is inscribed to the Sultan of Turkey>

1898 In the Wake of Spring: Love Songs and Lyrics (London: Bowyer Press, 1898)

1901 “The Portraiture of William Blake,” Brixtonian 15 (18, 25 Jan. 1901, “To be continued,” but apparently it wasn’t) <a plea for recognition of Blake>

1901 *“Blake Memorial,” Brixtonian 15 (2 Feb. 1901) <an appeal for money>

1901 “King Alfred Medal of 1901,” Westminster Review (Dec. 1901) <Wright (1907)>

1901 “The Millenium of Alfred the Great” from Brixtonian ([1901])

1901 Alfred the Great of Blessed Memory: Memorials Concerning England Long Anterior to the Reign of King Alfred to His Epoch Dug Out of Forgotten Lore (London: Bowyer Press, and Jones & Evans, 1901) 116 pp.; it reproduces “The Jacksonian Commemorative Medal, 1901” designed by himself for Alfred. In the Jackson sale by Goddard & Smith, 23-25 July 1923, #1091 was “About 13 reams of paper in the flat and unfolding [sic], being the Work on ‘Alfred the Great,’ written by Richard J. Jackson, E.S.A., President of the Dante Society, 1901.”

1901 In Memoriam the Lord Bishop of Oxford, the Right Revd. William Stubbs, D.D. (Camberwell, 1901), broadside

1902 Love Poems (London: Bowyer Press, 1902)

1907 Marius the Epicurean. “The Wright Form of Biography,” Academy No. 1826 (4 May 1907)

1912 *“William Blake: An Unlooked for Discovery,” South London Observer, 22, 29? June 1912 <Blake’s vine and fig tree were given him by George Romney>

1912 *“William Blake and John Linnell,” South London Observer (summer 1912), in two sections a week apart

1912 *“William Blake’s ‘Dulce Domum,’” South London Observer (summer 1912)

1912 *“William Blake’s Residence at Lambeth,” South London Observer (summer 1912) <a quarrel with the London County Council as to which house was the poet’s>

1913 *“William Blake at the Tate Gallery: Resident in Lambeth from 1793-1800,” South London Press, 31 Oct. 1913 <about the pictures on exhibition>

1913 *“The Vision of William Blake: Ode on his 156th Birthday,” South London Observer, 21 Nov. 1913

1913 *“William Blake—England’s Michael Angelo: Some noble thoughts of our poet-painter brought into the light of day for his 156th birthday November 28, 1913,” South London Observer, 26 Nov. 1913

1913 “The Immortal William Blake. The Memorial (Blank Verse) Sonnet for Blake’s 156th Birthday,” ([?Nov 1913]), separately issued with a portrait (copies in the John Johnson Collection in Bodley and the Tate)

1914 *“Felpham and the Poet-Painter Blake: Blake Society of Arts and Letters: Interesting Speech of the President,” Observer and West Sussex Recorder (27 May 1914)

1917 William Blake, The Book of Thel [Illustrated by] W.R. Kean (Lambeth: Printed as Manuscript [sic] for the Blake Society, [?1917])

1917 William Blake, Little Tom the Sailor (London, 1917)

1919 “The 162nd Year’s Mind of the Immortel [sic] William Blake, England’s Wondrous Mystic Poet, A Memorial Sonnet, by the Baron Antwerpen-Plantin, Richard C. Jackson,” (2 Aug. 1919), printed on blue paper (copy in the John Johnson Collection in Bodley)

1923 Will for effects valued at £4,673.19.6, heirs Henry Buxton Angier Ashton (solicitor, sole executor) and Gardner Teall (of The Authors Club, 7th Avenue at 56th Street, Carnegie Buildings, N.Y.), made 4 March 1923, probate 25 June 1923

n.d.

The Dream of Omar Khayyám ([n.p., n.d.]), pamphlet

Advertised but not seen

The Coming of the Bridegroom <ad in The Risen Life (1883)> Hymns and Poems on Various Occasions <ad in His Presence (1891)>

Lyrics of the Blessed Sacrament <ad in The Risen Life (1883)> Music for the Liturgy of the Blessed Sacrament <ad in His Presence (1891)>

Pearls of Great Price and Other Poems (1891) <ad in His Presence (1891)>

Thine and Mine: Poems and Hymns for the Sick and Weary <ad in His Presence (1891)>

Articles in Oxford University Herald, South London Observer, Camberwell and Peckham Times “and other papers” <Wright (1907)>

R.C. Jackson and Dr. Lee of Lambeth were the proprietors of The Church Echo <Wright (1907)>