ARTICLES

“Tenderness & Love Not Uninspird”: Blake’s Re-Vision of Sentimentalism in The Four Zoas

For Mercy has a human heart

Pity, a human face:

And Love, the human form divine,

And Peace, the human dress.

William Blake, “The Divine Image”

Pity would be no more,

If we did not make somebody Poor:

And Mercy no more could be,

If all were as happy as we;

Blake, “The Human Abstract”

William Blake’s epic poem The Four Zoas has been read in varying ways: as a dream, as a psychological account of fragmented consciousness, and as an attack on Newtonian science, to name a few.*↤ * I would like to thank Dennis Welch at Virginia Tech and John O’Brien and Jerome McGann at the University of Virginia for their helpful comments and suggestions during the preparation of this essay. For those critics also focusing on the physical state(s) of the manuscript itself, The Four Zoas is everything from an abandoned and tragic failure to a remarkable experiment with flexible poetics. Blake’s eclectic, syncretic mythology and the “unstable” status of this unfinished work welcome these readings. Begun c. 1797 (the date on the title page) and revised until possibly 1810 or even later (see Bentley 157-66), the epic grows out of a revolutionary decade for society and for the literary practices that influenced many of Blake’s earlier writings. One such revolution that has been largely overlooked in studies of The Four Zoas is the changing view of sentimentalism, which was a philosophical and literary movement especially prominent throughout the eighteenth century.1↤ 1. Although some scholars have noted the connection between Blake and sentimentality, most treatments of this subject are portions of a larger discussion, often related to gender and sexuality in Blake’s poetry (see my bibliography). One noteworthy article is Andrew Lincoln’s “Alluring the Heart to Virtue: Blake’s Europe,” in which the author examines “the rise of affective devotion or ‘the religion of the heart,’” “a religion grounded in affection [that was] seen as a most effective instrument of social harmony and control” (622, 623). Other helpful studies include Mary Kelly Persyn’s article on sensibility, chastity, and sacrifice in Jerusalem, and Judith Lee’s discussion of Blake’s Emanations. Riding a wave started by earlier critics who targeted sentimentalism, radical writers focused on its emphasis on emotion and sympathetic benevolence between individuals. But they also attacked the tendency of sentimentalism, unless guided by reason, to weaken or (as some saw it) “feminize” society, to encourage hypocrisy and self-gratifying charity, and to foster a predatory system of victimization. Their attack often took a gendered form, for critics saw sentimentalism as a dividing force between the sexes that also created weak victims or crafty tyrants within the sexes.

Blake points out these negative characteristics of sentimentalism in mythological terms with his vision of the fragmentation and fall of the Universal Man Albion into male and female parts, Zoas and Emanations. In the chaotic universe that results, sentimentalism is part of a “system” that perpetuates suffering in the fallen world, further dividing the sexes into their stereotypical roles. Although “feminine” sentimentality serves as a force for reunion and harmony, its connection with fallen nature and “vegetated” life in Blake’s mythology turns it into a trap, at best a Band-Aid on the mortal wound of the fall. For Blake, mutual sympathy in the fallen world requires the additional strength and guidance of inspired vision (initiating a fiery Last Judgment) in order to become truly redemptive, effective rather than merely affective. When recounting humanity’s “Resurrection to Unity” and “Regeneration” in The Four Zoas (4:4-5, E 301), Blake frequently uses sentimental conventions both to characterize fallen disorder and to show how it can be healed when incorporated into spiritual vision.

Although critics speak of the “Age of Sensibility,” the “cult of sensibility,” “sentimental literature,” and so forth, sensibility and/or sentimentality are often easier to describe than to define. Indeed, as Janet Todd points out in Sensibility: An Introduction, writers in the eighteenth century used the terms interchangeably and inconsistently (6).2↤ 2. Todd’s book serves its titular purpose extremely well for the general features of sentimentalism. For readers wishing to pursue this topic, some other important works on specific aspects of sentimentalism, such as its relation to culture/consumerism, politics, and sexuality, are listed in my bibliography. However, we can identify some crucial distinctions between these terms and, even more importantly, distinguish many of the overall movement’s other key terms and features that will appear again when we look at The Four Zoas.

In general, “sensibility” refers most directly to physical feelings and emotions, as well as to the reification and display of emotional refinement. Sensibility thus values delicacy and associated acts such as crying, kneeling, fainting, and charity, and it is—as sensibility makes clear—based on the natural responsiveness of the bodily senses. “Sentimentality” also emphasizes emotions and the body, but in a slightly different way. Sentiments are rational or moral reflections, in sentimentalism usually connected to or inspired by the emotions and related to the propriety of certain behaviors; thus, sentimentality brings the mind into closer relationship with the natural senses. As Jerome McGann succinctly puts it, “sensibility emphasizes the mind in the body, sentimentality the body in the mind” (7).3↤ 3. Jane Austen exploits the varying connotations of sentimental terms in Sense and Sensibility (begun 1797, published 1811) so as to critique/ parody the latter in contrast to the former; however, her novel still retains a great deal of sentimentality, positive and negative. The close connection between these two terms grows even closer because “The adjective ‘sentimental’” begin page 61 | ↑ back to top became a catchall phrase for sensibility and sentimentality (Todd 9). What is most important to recognize is the emphasis given to the body, to the physical senses, as a legitimate source of behavior and knowledge.4↤ 4. For this paper, I will use “sentimentality” for the faculty and “sentimentalism” for the movement that it fostered. For extended discussions and definitions of sentimental terminology, see Brissenden, chapter 2 and 98-118, and Hagstrum, Sex and Sensibility 5-10.

Given this prominence of the body, it makes sense that a key starting point for the sentimental movement in England is the empiricist, or “sensational” (Barker-Benfield 3), philosophy of John Locke. In his Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690), Locke identifies the physical senses as the source of our ideas. Subsequent philosophers, such as the third Earl of Shaftesbury and Francis Hutcheson, developed Locke’s views with the addition of morality and aesthetics, helping to define sentimentalism as a distinct movement by advocating the cultivation of virtue. Benevolence is probably the most crucial element of the Shaftesbury-Hutcheson brand of sentimentalism, especially since benevolence was “in this period a ‘manly’ attribute opposing ‘womanish’ self-interest and fear” (Todd 25). David Hume and Adam Smith are other important figures, the latter especially so with his Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759). In this work, Smith views the emotions and sympathy between individuals as valid social forces: by “entering into” another person via our imagination, we can sympathize with that person and form a relationship (2). More strikingly, his discussion of “unsocial,” “social,” and “selfish” passions (part 1, chapters 3, 4, and 5 respectively) and their role as determinant factors in one’s “merit” or “demerit” in society (part 2) goes far toward systematizing sentimentality in regard to public displays of sentiment and subsequent social status. Given Smith’s apparent exchange-value approach to human feelings, it is not surprising that he later authored the great economic treatise The Wealth of Nations (1776).

With these developments in sentimentalist philosophy, as well as in religion in general and Methodism in particular, literature became probably the most prominent venue in which the “cult of sensibility” practiced its art and expounded its principles.5↤ 5. Barker-Benfield rightly identifies the “cult” (and its constituent cults) as not just a literary trope, but also as an “epiphenomenon” extending across the eighteenth-century cultural spectrum, from religion to social behavior; he is most concerned with this sentimental culture’s relationship to “the rise of a consumer society” (xix). Along with Barker-Benfield on sentimental religion, see Lincoln, “Alluring.” In France, Jean-Jacques Rousseau united sentimental philosophy with fiction and confessional, emphasizing the natural, sensual component of human nature, and he had a strong influence on English sentimentalists. In England, Samuel Richardson, Sarah Fielding, and Laurence Sterne in fiction, and Hannah More, Thomas Gray, and Edward Young in poetry, were just a few of the authors contributing to the vast corpus of sentimentalism and establishing a distinctive “language of affective meanings” (McGann 6). Although the amount of sentimental literature was enormous, we can cull out some of the specific values that are crucial for understanding Blake’s approach to sentimental literature. Sentimental writers sought a heightened sense of pathos through stock characters—virtuous heroines, benevolent heroes, wizened beggars, distressed children—and trademark scenes of weeping, charity, and especially hostility reconciled by emotional interaction among said characters. Authors tried to forge a sympathetic, affective relationship between text and reader by depicting these “natural victims” and the antagonistic society or characters hounding them (Todd 3); a good reader was expected to respond with the appropriate sentiment, while neophytes gained valuable instruction through reading. What sentimental literature exploits, even requires, for its effect/affect, then, is a dichotomy of victim and victimizer. It codifies, as it were, a “system” of suffering and division while trying to create (and teach) sympathetic affections. This dichotomy, however problematic it may be for sentimentalism’s ostensible goals of mutual benevolence, most clearly manifests in relation to gender—the expected qualities and behaviors of each sex. Gender differences, in fact, largely define the system of (sexual) virtue and antagonism, be it within a domestic family setting or within society as a whole. As R. F. Brissenden famously puts it, “The paradigm cliché” of sentimental literature is “virtue in distress” (94), the situation in which we find the two most enduring sentimental stereotypes: the chaste but embattled woman and the good-hearted but doomed man of feeling.

The status of women in sentimental literature is indeed a pitiful one. Largely because of women’s “unique sexual suffering” and “bodily authenticity,” sensibility “stressed those qualities considered feminine in the sexual psychology of the time: intuitive sympathy, susceptibility, emotionalism and passivity” (Todd 110). In the foundational novels of Richardson especially, weak and chaste women become ideal sentimental, virtuous heroines. Clarissa Harlowe, for example, “is the symbol of virtuous sensibility” in Clarissa because of her “ailing body,” which signifies that she is “too good for the world, and feels too much” (Mullan 111). Helping to clarify this ideal and set the sentimental standards, a dichotomy exists even within representations of women: wicked women, to contrast with the ideal heroines, “simply lacked femininity and acquired masculine traits” (Todd 80). What we most commonly find in sentimental fiction, then, are laudably passive women who face threats to their “virtue” from males or some masculine antagonistic presence—victims and victimizers, such as Clarissa and the rapist Lovelace. In the face of such victimization, we also frequently find women (Pamela and Mrs. Jervis in Pamela, for instance) who come together to share the heroine’s suffering, which surely plays off stereotypical views of women as more emotional and closer to the body. And all too often, the chaste embodiment of virtue struggles in vain against her victimizer until she finds “no place to rest but the grave” (Allen 128). The sinister nature of sentimental femininity emerges in what these views imply: sentimental heroines need, as it were, to be persecuted “because sensibility, begin page 62 | ↑ back to top and therefore virtue, is most excited, and therefore most manifest, when threatened” (Mullan 124).6↤ 6. Richardson, writing to Lady Bradshaigh, is even more explicit on this dire necessity in his sentimental fiction: “Clarissa has the greatest of Triumphs even in this world. The greatest, I will venture to say, even in, and after the Outrage [of her rape], and because of the Outrage that ever Woman had” (qtd. in Mullan 66). And the sexual dimension of virtue’s distress is crucial, Hagstrum makes clear, because in many cases rape (threatened or carried out), “far from spoiling the sensuality [in a novel], actually heightens it for both sexes” (Sex and Sensibility 201). There is thus a dark subtext, as it were, in sentimental literature: much as occurs in some shocking views of rape (“She was asking for it”), the sentimental victim often seems complicit in, or even responsible for, her attack.

The “man of feeling” fares little better than his female counterpart. Because sentimentalism was originally a male construct (from Shaftesbury, Hutcheson, et al.) that appropriated “feminine” qualities of emotional and bodily responsiveness, male sentimental characters face fates similar to those of sentimental women. The man of feeling fills his role by his “outflowings of emotion,” which “teach response more than virtuous action” (Todd 92), so any charitable acts play second fiddle to his hyperbolic sympathy. He therefore sheds tears at almost every turn and is nearly incapacitated by any and every scene that stirs his affections; he is mastered by, rather than master of, his overpowering senses and feelings. For example, during a pitiful story told by an insane mother, Harley in Henry Mackenzie’s The Man of Feeling (1771) paid “the tribute of some tears,” “bathed [her hand] with his tears,” and then “burst into tears” when departing (26, 27).7↤ 7. An “Index to Tears” appeared in the first edition of The Man of Feeling, giving line and page citations for readers who wanted to study up on cause and effect, scene and response, in the sentimental system of weeping. See Mackenzie 110-11. Weakened like Harley, the male sentimental “hero” can hardly stand up to the hostile and unfeeling society that opposes him, so that his heartfelt expressions of benevolence and tenderness make him an easy victim. In general, then, a man of feeling is irrevocably alienated from society because of his sentimentality, or he inevitably meets an early death, in either case accomplishing little or nothing for the greater good. Once again, the system of suffering becomes self-indulgent and self-sustaining, and the victims “invite” the forces attacking them in order to function as sympathetic characters. Gender identity and difference, both for female and male characters, thus play determinant roles in the “order” of this sentimental system.

When we turn to The Four Zoas, we find a similarly divided and antagonistic situation. In Blake’s cosmological myth, the unity of Albion has given way to warfare between the sexes and all of the characters, wreaking havoc in the entire universal order and growing ever more calamitous. Blake begins his epic in medias res, in the world as we know it, and things are far from harmonious or Edenic. The division of the androgynous Zoas into male Zoas and female Emanations is the most glaring evidence that something has gone horribly wrong. Besides the Zoas and Emanations, Blake’s mythology grows chaotically larger as these parts of Albion’s ailing (sentimental) body split and transform into Spectres, Shadows, Spirits, Orc the “reborn” Luvah, and countless sons and daughters of various sorts. As is implied here, the key concept is fragmentation.

The very presence of divided sexes is in fact catastrophic. This is the case, according to Blake, because in Eternity Albion is androgynous. However, the exact natures of Albion and the Zoas are only known by “the Heavenly Father,” which makes the Eternal Self eternally tricky, especially when an “Individual” tries to understand it from below (FZ 3:7-8, E 301). While Blake asserts Albion’s androgyny, his language and general presentation of Eternal life create a great deal of difficulty in regard to the “sex” of Eternal beings. Specifically, Blake’s is a masculine (at least linguistically, at most ontologically) Eternity of Albion the “Man” and the “Eternal Brotherhood.” As Leopold Damrosch explains, the consequence is that it appears as if “the female is fully integrated into the male” and that “The androgynous self [Albion] is, in effect, a male self with a female element within it” (182).8↤ 8. Critical opinion has long been divided on this issue and its implications for Blake’s opinions, cosmology, and poetics. For instance, Irene Tayler sheds a more positive light than Damrosch on the gender equality of Blake’s Eternal androgyne, while Anne K. Mellor and Susan Fox emphasize Blake’s subordination of the female and the feminine. The female is not separate but integrated, internalized, even more obviously than the male. Blake’s writings frequently seem to bear this opinion out, especially when he deals with fallen life. For example, Ahania becomes Urizen’s “Shadowy Feminine Semblance,” and Urizen is “Astonishd & Confounded” to see “Her shadowy form now Separate,” for now “Two wills they had two intellects & not as in times of old” (FZ 30:23, E 319; 30:45-48, E 320). The separation of an originally integrated portion of the self, whether that self is androgynous or to some extent masculine, makes the female extremely problematic in Blake’s mythology, since he emphasizes its emanated, secondary nature. In its most negative forms, the female will becomes the dreaded “Female Will,” while femininity itself is “a symbol of otherness” representing “Whatever Blake cannot reconcile himself to in the phenomenological world—bodies, matter, nature, physical space” (Damrosch 183, 188). Thus, Blake’s females have a status similar to that of women in sentimental literature, being linked to the body, senses, and emotions, and in turn to the physical world, nature, and generation.9↤ 9. For instance, Otto identifies Enitharmon as “the form/body of the fallen world” and “the shape of [all] the Zoas’ loss,” as well as “the body of imagination,” while Vala is “the sexual body” and Enion “the sensitive body” (85, 79). Just as writers and critics of sentimentalism characterize the (emotional) body as a “feminine” realm, Blake associates the begin page 63 | ↑ back to top female identity with material, corporeal reality. As we shall see, although the female Emanations serve a crucial role in the fallen world (as its very “ground,” as it were), they are essentially anomalies and indicators of its fallenness. But, as Helen P. Bruder also asserts, in “giving a form to sexual error,” Blake was as much “a searching critic of patriarchy” as a “hectoring misogynist” (182).10↤ 10. Alicia Ostriker gives a fine treatment of Blake and the woman question in her outline of the “four Blakes.” While Blake’s misogyny or lack thereof is an important topic, it is not crucial to my discussion. Although the female sex carries much of the fallen world’s negative burden, the fallen male Zoas are by no means exemplars of “redemptive” behavior, and their depravity is inherently tied to their separate sexual identity as males. With the fall, and only with the fall, do the sexes become distinct.

But how does the presence of two sexes in The Four Zoas indicate both that Blake recognized the sexual tensions fostered and exploited by sentimental literature, and that he critiqued the sentimental system as a whole? We can answer this question by first examining reactions to sentimentalism, in particular the criticisms made by radical writers. These writers decried the negative influence of sentimentalism on human nature, an influence that they often traced back to the movement’s conventional characters and behaviors. In turn, the harmful effects that radical writers censured shed light on The Four Zoas because they correspond in significant ways to Blake’s portrayal of the fallen world and its sexually divided inhabitants.

Despite its enduring presence, even by the 1770s “sentimentality” was a derogatory label indicating affectation, self-indulgence, and overbearing shows of emotion. Particularly troubling for many was the feminized quality of sentimentalism, creating hyper-feminine women and effeminate men and thus weakening society as a whole. Sentimentalism’s fetishizing of the feminine created a cultural dichotomy, with one group valuing the community-building power of “female qualities” and another group fearing effeminacy, advocating male dominance, and seeing woman’s nature as “contingent” (Todd 20). The critics found feminine “self-indulgent physicality and . . . self-contemplating vanity” in sentimental literature as a whole (62); even worse, they scorned it for adversely influencing readers—largely women.

The revolutionary events of the 1790s ushered in a new group of critics and sentimentalists, with radical writers fighting for social change and systemic reform rather than the indulgent cultivation of feelings. According to Chris Jones, “Radical writers of sensibility stressed qualities in direct contrast to the popular degenerate model of the ‘man of feeling’ in emphasizing action and intervention,” retaining an emphasis on the emotions but dismissing “self-centred passions” for more universal feelings under the aegis of rational benevolence (9). Because “the whole [sentimental] movement had been branded with weakness and irresponsibility” (17), it was both attacked and modified by revolutionaries such as William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft, as well as later Romantics such as Jane Austen and William Wordsworth. As shown in Songs of Innocence (1789), Blake absorbed the culture of sentiment: his innocent speakers and pastoral lyrics, such as in “The Lamb” and “Nurse’s Song,” depict a heartfelt sympathy between individuals similar to the ideal of sentimentalism. Yet he also critiqued sentimental culture, as in Visions of the Daughters of Albion (1793) and Songs of Experience (1794). In Visions, the main characters both reflect and respond to sentimental stereotypes. We find the sentimental triangle of (here emboldened) rape victim, tyrannical rapist, and emotionally self-absorbed male in Oothoon, Bromion, and Theotormon. In Songs of Experience, Blake’s weeping chimney sweeps (“The Chimney Sweeper”) or fussy infants (“Infant Sorrow”), while pathetic images, confront a cold society—typified in “The Human Abstract”—that often professes sympathetic bonds but produces only a land of misery. These works, along with some of his commercial book illustrations,11↤ 11. Lincoln observes that Blake did engravings for works by sentimental novelists such as Richardson, Sterne, and Sarah Fielding (“Alluring” 630n30). help to place Blake within the cultural debate surrounding sentimentalism in the 1790s, even if he did not follow some of his contemporaries and launch an explicit campaign for or against the tradition.

Because Wollstonecraft attacks sentimental conventions while occasionally incorporating them into her arguments, her Vindication of the Rights of Men (1790) and Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) provide excellent touchstones for the radical reworking of sentimentalism and for Blake’s later critiques. As Dennis Welch has pointed out, she likely had some influence on Blake, who designed and engraved illustrations for her Original Stories from Real Life (1788). And although Michael Ackland suggests that Blake owed much to her Rights of Woman for his view of sexual relationships and his attempts to create harmony between the sexes, Ackland does not recognize some of the specific parallels between both of the Vindications and Blake’s works.

In the Rights of Men, Wollstonecraft upbraids Edmund Burke for using “sentimental jargon, which has long been current in conversation, and even in books of morals, though it never received the regal stamp of reason” “(62; all italics in the original henceforth unless noted otherwise). She identifies this jargon as an expression of blatant “sensibility,” which she attacks for making men “resigned to their fate” and unable “to labour to increase human happiness by extirpating error, [which] is a manly godlike affection” (89). Sentimentalism values “sympathetic emotion” and “mechanical instinctive sensations” so much that it interferes with reason and active virtue. Wollstonecraft also finds that sentimentalism has created a split between and within the sexes, which has in turn corrupted society. Responding to the excesses of sentiment in begin page 64 | ↑ back to top Burke’s Reflections, she ridicules this “good natured man” for the “amiable weakness of his mind” (81). But the man of feeling is only one male creature crawling out of the sentimental swamp, for “mild affectionate sensibility only renders a man more ingeniously cruel” (79), thus creating overly malicious as well as overly weak men.

In the Rights of Woman, Wollstonecraft especially laments how women “become the prey of their senses, delicately termed sensibility”—she calls them mere “creatures of sensation”—as a result of “Novels, music, poetry, and gallantry” (177). Just as men are made either weak or cruel by sentimentalism, so women are made “either abject slaves or capricious tyrants” (158). The latter exhibit “artificial weakness” and have “a propensity to tyrannize” with their “cunning” in order to “excite desire” in men, who in their own right need to become “more chaste” (113). But, deluded by sentimental notions of ideal feminine chastity, men force women to be chaste and yet indulge themselves in novels, “whilst men carry the same vitiated taste into life, and fly for amusement to the wanton” after abandoning virtue (333). Clearly, Wollstonecraft recognizes how “the reveries of the stupid novelists” foster the debilitating “romantic twist of the mind, which has been very properly termed sentimental” (330). But when she speaks of a poet or artist “vibrating with each emotion” as he/she works (309) or makes her own impassioned appeals to sensibility (rational here, more traditional in her novels), it is hard not to see the continued influence of sentimentalism even on this radical writer.

Ackland is convincing, then, as he traces Blake’s “protracted exploration of embattled sexuality” to Wollstonecraft (172), but he misses the strong critique of sentimentalism in Wollstonecraft’s treatises and in Blake’s poetry. Judith Lee comes much closer when she points to Wollstonecraft’s Rights of Woman “as a paradigm for [Blake’s] portrayal of women in an attempt to resolve the contradictions between traditional stereotypes and his revolutionary vision” (132). Sentimentalism is, I think, a key concern in Blake’s writings because he addresses all of the major problems that fellow radicals found in this movement: sexual tensions, weakened or tyrannical men, victimized or manipulative women, and a system of self-indulgent suffering. We can see such problems in The Four Zoas, which treats contemporary social conditions in cosmological, mythological, and psychological terms.12↤ 12. Marshall Brown argues that Blake “resolutely continued the vein of sensibility,” struggling to “convert the psychic economy of sensibility directly into a blinding vision of universal truth” (103). I feel that Brown is a little too enthusiastic and misses Blake’s evident criticisms of sentimentalism, as well as the importance of the “psychic economy” evident in the fourfold myth of the Zoas, which are interdependent—harmoniously in Eternity and discordantly when fallen. Nevertheless, Brown’s argument remains plausible in light of a letter that Blake wrote to his patron William Hayley on 16 July 1804 (and so after his time at Felpham). Thanking Hayley for some books, Blake writes, “[Samuel] Richardson has won my heart I will again read Clarissa &c they must be admirable I was too hasty in my perusal of them to percieve all their beauty” (E 754). Blake’s statement here seems to put him entirely in sympathy with the sentimentality expressed (and codified) by Richardson, which could make him less likely to criticize sentimentalism in his writings. It also suggests that, despite engraving illustrations for sentimental authors (and perhaps reading some of their works along the way?), Blake actually read sentimental literature long after beginning his poem Vala. But because of this relative lateness, the majority of the poem itself still may be imbued with the radical spirit and its critique of sentimentalism as both a literary and a cultural phenomenon; later material, such as Night VIII, may be in question. In addition, we should also consider Blake’s audience. Blake’s positive comments on Richardson’s novels, sent by Hayley with other books, may reflect his appreciation for Hayley’s continuing support. This is not to charge Blake with disingenuousness or to ignore his obviously favorable response, but I think it is important to recognize that his opinions and views expressed in letters may at times be complicated. Finally, Blake’s sentiments here also may be part of his personal development that culminated in a renewal of distinctly Christian vision in 1804, which he recounts in a letter to Hayley on 23 October 1804 (E 756-57) and which might make him more “susceptible” to the piety expressed by Richardson’s heroines. Taking into account all of these factors, I think that we must rely primarily on internal evidence from The Four Zoas to gauge Blake’s views on sentimentalism as they developed over the course of the poem’s composition and revision. At the most basic thematic level, Albion’s fragmentation into the four Zoas and their further fragmentation into warring male and female identities point to what recent critics are beginning to see as a consequence of sentimentalism. According to Marshall Brown, “The sensible self is an unfathomable mystery,” whose “Protean fragmentation” eighteenth-century writers treat at great length (86). Because sentimentality “reduces self as well as society to pure sentiment,” a “fragmentation of personality” results “that forces us to adopt Sentimental responses” and puts us at the mercy of our senses and emotions (Allen 128, 122). The fragmentation of the sentimental self is also related to the divisions of the sexes in sentimental literature in a continual interplay of cause and effect, making it nearly impossible to pinpoint one as cause or effect. Similarly, for Blake, “sexual identity is the most defining yet problematic aspect of selfhood” (Bruder 183), and Albion’s self becomes both sexed and problematic with the fall. Blake’s awareness of the sexual nature of selfhood helps us to answer our question of how the two sexes in his mythology relate his work to sentimental literature: the personalities and behaviors of Blake’s characters often seem to exhibit some of the trademarks of sentimentalism. In turn, the presence of sentimentality within the fallen world marks it as such, a sign that the androgynous Eternal Self has divided into two separate, alienated sexes. Blake’s starting point in the myth of fragmented Albion thus projects the personal and social consequences of sentimentalism to a cosmic level and defines them as concomitant with the fall.

Indeed, the opening scene of The Four Zoas resembles many scenes in sentimental fiction. The action begins “with Tharmas Parent power” pouring out a flood of sorrow:

Lost! Lost! Lost! are my Emanations Enion O Enionbegin page 65 | ↑ back to top

We are become a Victim to the Living We hide in secret

I have hidden Jerusalem in Silent Contrition O Pity Me

I will build thee a Labyrinth also O pity me (FZ 4:7-10, E 301)

So here we have Tharmas, the sensory bedrock of humanity and the first male character we meet in the fallen world, pouring out his sea of tears and bewailing the pity that washes over him. And in the same opening scene, Tharmas’s Emanation Enion responds affectively to his woe with her equally troubled emotions. “Thy fear has made me tremble thy terrors have surrounded me,” she says, and these terrors lead her to expect (or resign herself to?) destruction: “I am almost Extinct & soon shall be a Shadow in Oblivion / Unless some way can be found that I may look upon thee & live” (FZ 4:17, 22-23, E 301). This threatening loss of identity manifests the serious danger of excess sentiment pointed out by Brown and Allen. Enion’s affective sympathy for, and with, Tharmas is so complete that it puts her under the control of her feelings, leaving her unable to maintain her sense of self against the onrushing tide of his woe and fear. Although Enion cries out to him, he is powerless to help her, completely divided and himself a victim of humanity’s disorder. He can only turn “round the circle of Destiny” before sinking “down into the sea a pale white corse / In torment” and flowing “among [Enion’s] filmy Woof” (5:11, 13-14, E 302). The direct result of this dissolution is even more tragic: the Spectre of Tharmas (“insane & most / Deformd” [5:38-39, E 303]) is born from his corpse and is clothed by Enion’s laboring for “Nine days” and “nine dark sleepless nights” at her loom (5:23, E 302). In his spectrous form, Tharmas becomes a tyrannical male, “pure” and “Exalted in terrific Pride,” while describing Enion as a “Diminutive husk & shell” and as “polluted” (6:8-10, E 303). As with so many persecuted heroines of sentimental fiction, her pollution does not dissuade him from “Mingling his horrible brightness with her tender limbs,” a rape that in turn transforms her into “a bright wonder that Nature shudder’d at / Half Woman & half Spectre” (7:8-10, E 304)—and then into a mother.

This first scene of The Four Zoas incorporates three of the most prominent sentimental stereotypes: the weakened man of feeling, the abused woman driven to destruction, and the brutally abusive male, a cast hearkening back to that of Visions. One example of a comparable interaction between such types appears in Mackenzie’s The Man of Feeling, which shows that these gender stereotypes are both sentimental in nature and part of a sentimental exchange system.13↤ 13. According to Barker-Benfield, Smith’s social-exchange sentimentalism provided a major source for Mackenzie: “Mackenzie lived in the Edinburgh of Hume and Smith and his novels preached the latter’s theory of moral sentiments” (142). The scene in question occurs when Miss Atkins, a prostitute, narrates her woeful tale to the hero, Harley. In this sentimental economy, the price of goods is paid with tears, so Harley dutifully weeps himself to the point of being dumb, which in turn causes Miss Atkins’s “fortitude . . . to fail at the sight” (Mackenzie 50). Although the bartering begins with the woman here, the affective exchange of a sad story and subsequent emotional responses is similar to that in The Four Zoas: Tharmas’s lament, Enion’s fearful answer, and Tharmas’s dissolution into Enion’s woof. When Miss Atkins’s father bursts into the room and explodes with rage over the lost honor of his daughter, we see the sort of antagonistic male that Blake transforms into the Spectre of Tharmas. Miss Atkins, having established her status as victim in her tale, faces further hardship as she falls “prostrate at [her father’s] feet” and begs him for “the death she deserves.” Unlike Blake’s Spectre, however, Miss Atkins’s father “burst[s] into tears” and does not punish (or rape!) her. Matters end happily when even this hostile male “[mingles] his tears with hers” (51). Despite the different endings—an exemplary sentimental encounter in the novel versus a critical representation of sentimentalism’s dark side in the poem—both Mackenzie and Blake depict how characters influence each other through an exchange of sentiment, and both do so by using three sentimental stereotypes.

Perhaps an even more striking instance of sentimental “exchange” between characters in The Four Zoas comes at the end of Night II. This scene opens with Los and Enitharmon sowing contention between Urizen and Ahania as Enion laments and Urizen—having already puffed himself up as “God the terrible destroyer & not the Saviour”—watches helplessly in dread (FZ 12:26, E 307). Los begins with a self-pitying account of being “forsaken” and “mockd” by the very lowest creatures in nature (34:21, E 323). Less than sympathetic, Enitharmon calls him her “slave,” paradoxically “strong” while she is “weak” (34:46, E 323). Because Los had earlier abused Enitharmon and then repented out of pity for her suffering (11:3, E 306; 12:40-43, E 307), his subsequent “enslavement” to her shows a remarkable parallel to Wollstonecraft’s point about apparently weak, sentimental women often being made tyrants by male oppression. Los has certainly fallen under Enitharmon’s newfound power, for he can only languish “in deep sobs . . . till dead he also fell” when she deserts him (34:54, E 323). Blake accentuates the begin page 67 | ↑ back to top cunning nature of her control, labeling her song of exaltation over Los’s grief a “Rapturous delusive trance” produced by her delight at having power over Los and other men (34:93, E 324). Responsive to his counterpart’s rising emotions, Los revives through the song and finds sufficient energy to drive Enion and Ahania (her female rivals?) “into the deathful infinite” (34:97, E 324). This situation exemplifies what Wollstonecraft so zealously argues, that sentimentality pushes the sexes apart and fosters a system of emotional manipulation and physical cruelty based on their gender differences.

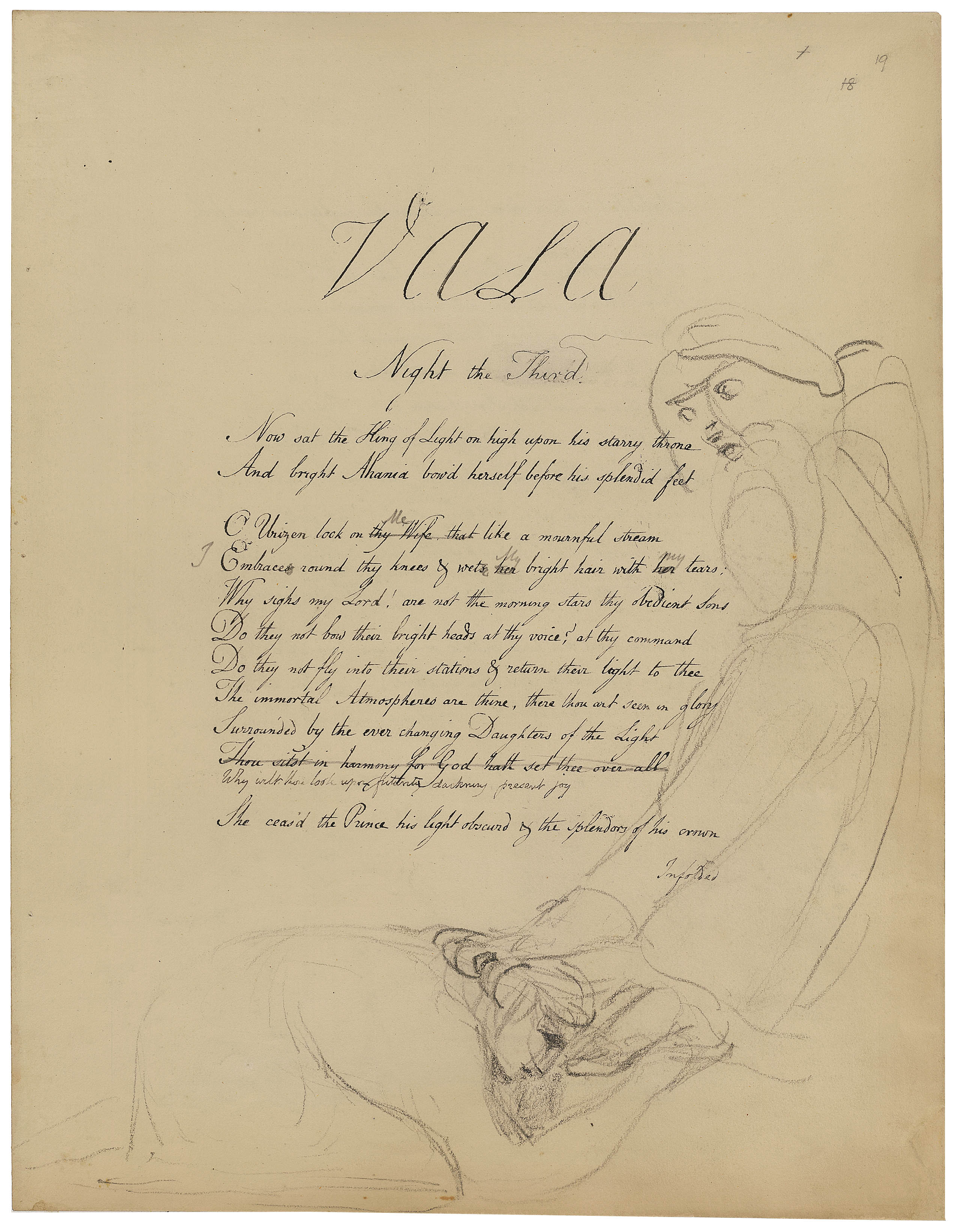

In this same scene, Enion utters her famous “Experience” lament and paints a series of pathetic pictures such as “the dog . . . at the wintry door, the ox in the slaughter house” and “the captive in chains & the poor in the prison, & the soldier

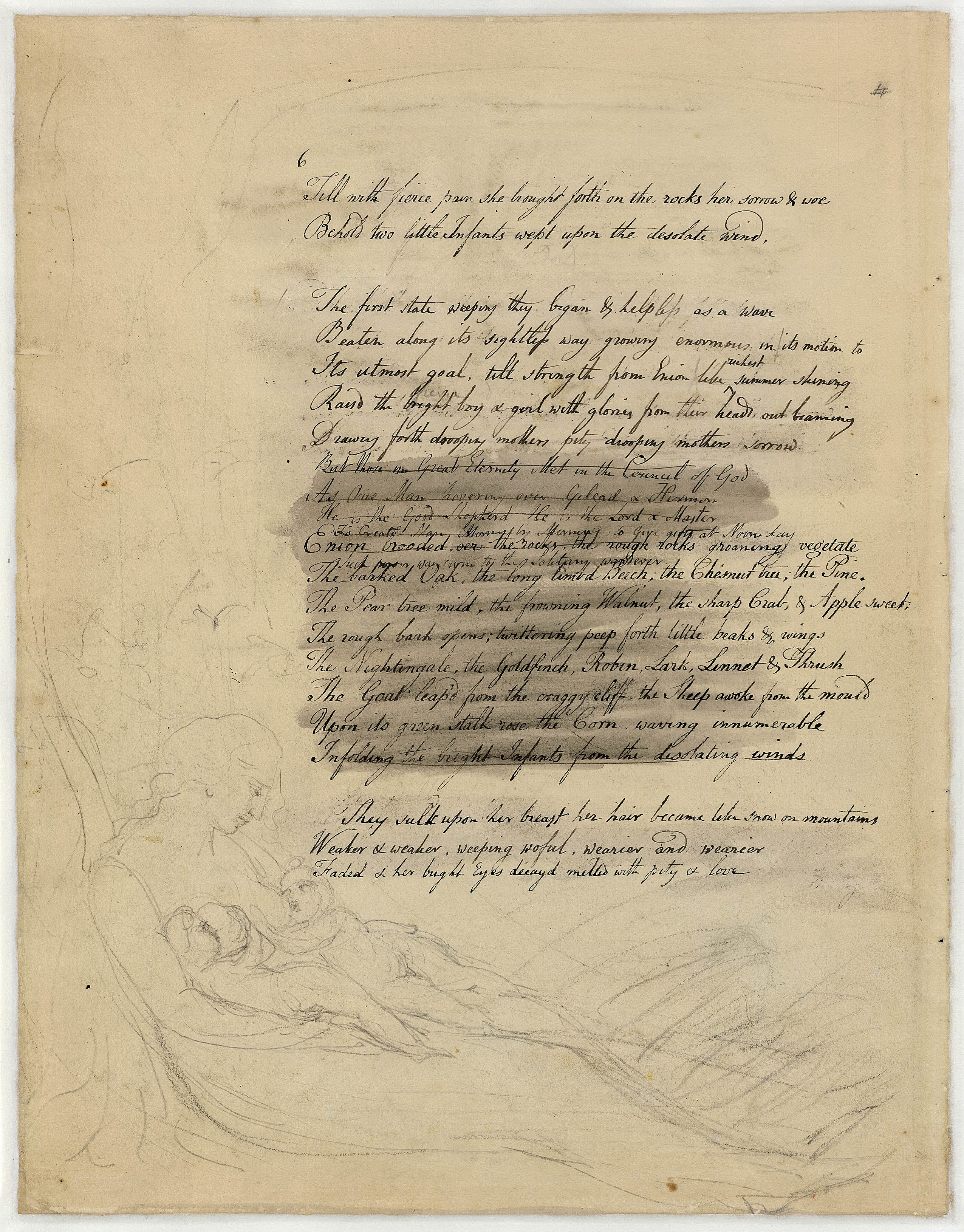

in the field” (FZ 36:4-10, E 325); these are all sufferers whom she identifies and sympathizes with, in contrast to those who rejoice in and ignore the misery. The affective power of Enion’s song is clear, for Ahania hears and, as if haunted by the images in Enion’s lament, “never from that moment could . . . rest upon her pillow” (36:19, E 326). But when Ahania comes to Urizen in the opening of Night III, it seems that Enion’s weakness (she sings from “the margin of Non Entity” [36:17, E 326]) has also affected her: Ahania subjects herself before Urizen’s throne, pleading with her male counterpart in vain (illus. 2). While the sentimental imagery employed by the Emanations in their songs is worth noting, more important is the way in which the characters affect each other with that imagery. Los cries and dies, Enitharmon sings in pride and begin page 68 | ↑ back to top revives him, Enion wails over Los’s antagonism, and Ahania is moved to seek her counterpart in meekness. Much as he does in Night I, when Tharmas melts into Enion’s woof and is immediately reborn as his own antithesis (the hypocritical rapist Spectre), Blake here problematizes our sympathetic identification with these characters, which is likely to be our first reaction. Forced to question our emotional, heartfelt response, we may also begin to question the validity of all such responses and their causes. Further, Blake shows just how complicit each type of character is in the suffering of the others, how they actually transform into each other, and how they instigate each other’s actions. The sentimental system of affective responsiveness is not only a system of exploitation, but also a system to be exploited for selfish ends rather than benevolent community building. And, as we saw above, the novelist’s system of suffering feeds itself: just as every Clarissa needs a Lovelace to threaten (and thus make manifest) her pathetic heroism, so every Oothoon needs a Bromion and every Enion needs a Spectre of Tharmas.In The Four Zoas, sentimentalism is not only problematic because of its fracturing, exploitative tendencies; it is also consistently negative because of the “feminine” or “feminizing” qualities that many eighteenth-century critics decried. Fallen life is, in many ways, “sentimental” for Blake because begin page 69 | ↑ back to top

“it is inseparable from the world of Generation, of mothers and weeping babies, of the matter and substance which are supposed to be nonentity but in fact seem all too real” (Damrosch 170). Mothers and weeping babies are the stock in trade of sentimentalism, prototypically weak creatures that so easily provoke affective responses. Thus, Blake consistently associates sentimental images of birth, children, the family, and nature with “vegetating” and the continual fall from Eternity. The birth of Los and Enitharmon after Enion’s rape in Night I is ostensibly a moment of potential happiness. Indeed, the illustration on page 8 (illus. 3) depicts a rather beautiful image of two tiny babes suckling their smiling mother’s breasts. But the text makes clear that these babes are the physical manifestations of Enion’s “sorrow & woe” (FZ 8:1, E 304). They exploit her “drooping mothers pity” and, “in pride and haughty joy,” they draw her “Into Non Entity” as she gives “them all her spectrous life” (8:7-9:8, E 304), a situation depicted in the very next illustration (illus. 4).14↤ 14. Blake washed a passage from this scene that more closely associates the birth of the children with animal and vegetable life, all of which relate to the verb “vegetate” (see E 823-24). Although likely meaning to cancel this passage, Blake associates physical birth with “vegetating” elsewhere, such as with the “vegetated body” (104:37, E 378). In addition, Enitharmon’s song begin page 70 | ↑ back to top over the dead Los in Night II includes images of nature and the “weeping babe,” and when she exclaims, “For every thing that lives is holy,” the context throws a remarkably negative light on this famous Blakean assertion (34:81, 34:80, E 324).15↤ 15. This assertion is used much more positively at the close of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (plate 27, E 45), in Visions of the Daughters of Albion (8:10, E 51), and in America a Prophecy (8:13, E 54). As Enitharmon sings of her new power and her desire for control, following as it does the problematic portrayal of her and Los’s birth, it is hard to join in and exclaim that physical life is indeed “holy.”The birth of Orc in Night V is particularly troubling in this respect. In reaction to Orc’s too-close relationship with his mother Enitharmon, Los the father “bound down her loved Joy” with “the chain of Jealousy” out of “Love of Parent Storgous Appetite Craving” (FZ 60:22-61:10, E 341). However, both parents suffer “all the sorrow Parents feel” and return in vain to free their son; even the narrator is overcome, only capable of making a trademark sentimental comment to the reader: “all their lamentations / I write not here but all their after life was lamentation” (62:10, E 342; 63:8-9, E 343). Once again, Blake makes it impossible for us to feel true sympathy for his characters. As in “Infant Sorrow,” we react negatively to these parents because of their complicity in their bound child’s suffering; nor can we fully sympathize with the child Orc, since birth itself is suspect as a continual fragmentation of fragments. Rather than encourage our sympathy with parents or child, Blake exploits sentimental conventions in order to call them into question, here with babes and weeping parents as representations of the basis of sentimentality, the physical or “vegetated” body itself.16↤ 16. The problematic nature of childbirth in a world of systematized sexuality is an enduring concern for Blake. David Aers notes that, in Visions, “The activity of begetting children is . . . engulfed in [a] closed world and the infant’s sexual life is doomed [in the] ghastly circle of ‘The Mental Traveller’” (“Blake: Sex, Society and Ideology” 30).

When in Night II Blake describes how “Luvah was cast into the Furnaces of affliction & sealed” while “Vala fed in cruel delight, the furnaces with fire” (FZ 25:40-41, E 317), he shows how the war between the fallen sexes is itself the reason why birth in the fallen world is vegetative and deformative.17↤ 17. “Infant Sorrow” is again a helpful parallel, exemplifying how tensions between parents are directly “reborn” in their offspring. Once again, we can see here the sentimental system at work, with a male subjected to a cruel, cunning female whom he himself “nurturd” and “fed . . . with my rains & dews” until she mutated from an “Earth-worm” to “A scaled Serpent” to “a Dragon” to “a little weeping Infant” (26:7-27:2, E 317). Although this male figure pities a smaller, fragile creature (the worm), his actions are part of a system that transforms pitiable and sentimental objects into deadly dragons. Indeed, his complicity is obvious (albeit not to him), for he proudly calls himself the “King” of the female as he narrates her metamorphosis (26:5, E 317). The sexual symbolism and tension in this passage are powerful, becoming almost disturbing in the illustration of deformed sexual creatures accompanying it (illus. 5).18↤ 18. In this series of designs from manuscript p. 26, perhaps the most famous and most reproduced, we can see breasts on the top figure, a woman gripping an erased penis and scrotum in the next figure, and a vagina in the next figure. Many other illustrations to the poem, especially in Nights II and III, are even more dramatically representative of the sexual strife that characterizes the fallen world. These accompanying designs, with their various bodiless and fetishized genitalia or their startling acts of copulation, only manifest and intensify the fighting, frustrations, and entrapments that occur between characters in the text. Blake also presents a situation that Wollstonecraft describes in her attack on sentimental literature: male oppression, especially in the form of improper education and reading, produces conniving women who exploit male desire so as to gain power. Blake, however, articulates this argument in nightmare images. The females in Blake’s fallen world are, like Wollstonecraft’s, most often either helpless or deceitful, while the males are weak, hypocritical, or cruel. Despite sentimental sympathies, there is no true harmony.

I have spoken of sentimentalism and its sexual strife as a negative, even predatory “system” in The Four Zoas because I think that Blake compels us to see it in this way. Although characters of both sexes are guilty of powermongering, sentimentalism by Blake’s time is closely aligned with femininity. But Blake will not let us forget that pity and sentimentality have also become bound up in a social “law” operating under the moral law of Urizen, fallen reason. The social exchanges of Adam Smith and “bartering” with tears in The Man of Feeling are only two examples of what Blake seems to recognize. Even worse, in fallen life, the Pity that has “a human face” too easily becomes the hypocritical Pity that “would be no more / If we did not make somebody Poor” (“The Divine Image” 18:10, E 12; “The Human Abstract” 47:1-2, E 27). Sympathy degenerates into a source of control, not of affection.

This law of sentimentality appears most explicitly in The Four Zoas during Urizen’s travels in Nights VI and VII. In Night VI, the tyrannical Urizen at one moment looks like a sympathetic character, “Writing in bitter tears & groans,” except that he writes “in books of iron & brass” containing his laws of moral virtue (FZ 70:3, E 347). (It is inviting to see Urizen’s tears and groans as part of what he writes, as if he were truly codifying laws of sentimentality like one of Wollstonecraft’s “stupid novelists.”) While doing so, he views “The ruind spirits once his children & the children of Luvah” in the Abyss (70:6, E 347). In what follows, Blake again sets up a sentimental tableau only to undercut it quickly. As if fed by Urizen’s woe, each soul in the Abyss “partakes of [another’s] dire woes & mutual returns the pang” (70:16, E 347). Despite these affective responses, which would potentially ease the terrors of the void, the ultimate response is the outbreak of war! When Urizen later comes upon Orc and expresses sympathy, the chained boy calls his bluff: “Curse thy hoary brows. What dost thou in this deep / Thy Pity I contemn scatter thy snows elsewhere” (78:42-43, E 354). But Urizen is persistent, begin page 71 | ↑ back to top

begin page 72 | ↑ back to top and when he begins to instruct his captive audience (Orc), the “Moral Duty” (80:3, E 355) that this lawgiver expounds includes rules for manipulating the powerless and poor with false shows of emotion until they are “as spaniels . . . taught with art” (80:9-21, E 355). “Spaniels” could apply equally to men of feeling and to helpless female victims in the “art” “art” of sentimental literature. What is most interesting here is that Urizen’s laws, his freezing “snows” of pity, are the very same as Ahania’s “laws of obedience & insincerity,” which Urizen abhorred in Night III (43:10-11, E 329). However, to be more accurate, Ahania’s laws are in fact Urizen’s laws, since she is his feminine portion now separated from him. Thus, when she confronted him in Night III with his own sublimated laws, hoisting him on his own (phallic) petard, he reacted with typical violence by throwing her “from his bosom” and “far into Non Entity” (43:24-44:5, E 329).19↤ 19. See Otto on the significance of the phallus in The Four Zoas and its relation to Urizen’s religion/law. Again we find the fragmented self and the sexes caught in a sort of whirlpool of origins and causality.For Blake, all systems and laws, especially of morality and human behavior, are threads in the web of Urizen and are thus dangerous. This is particularly true of sentimentalism because, as Urizen’s lesson to Orc in Night VII makes clear, affect can be manipulated for tyrannical ends far too effectively. The “sexual code” of sentimental law is also troubling in relation to The Four Zoas, since it inculcated self-repressive “delicacy” even while praising natural responses and maintaining an intimate association between that virtue and sensual desire (Barker-Benfield 299; Hagstrum, Sex and Sensibility 75). But sentimentalism is even more craven and harmful when one engages in its practices for the wrong reasons. The case of Los in Night IV illustrates this point. Los and Tharmas confront each other, each recounting his tale of woe and pity at the separations that have occurred, and then Tharmas bids Los to build the universe—that is, to give Urizen a physical body. Completing his task in seven ages of woe, Los sees the form that he has created and, “terrifid at the shapes / Enslavd humanity put on he became what he beheld / He became what he was doing he was himself transformd” (FZ 55:21-23, E 338; my italics). Through Los’s calamity, Blake presents the ultimate danger of trying to “enter into” another along the lines expounded by sentimentalists, who based the act on a sympathetic reaction to another individual’s worldly, visible hardship and, in the case of Smith, connected it with social standing.20↤ 20. Stephen Cox calls Smith’s Theory of Mortal Sentiments “a treatise on the educational process that enables people of sensibility to internalize social expectations and incorporate them into consciousness, idealizing yet personalizing them” (67). Because Los reacts to Urizen’s physical shape as it forms before him, he cannot penetrate the suffering, pathetic body, and so he gets trapped by the superficial. To become what one beholds in this way “defines a lapse of imagination. It is a romantic figure of visionary catastrophe” (McGann 66; my italics), so Los actually loses his vision and gets transfixed by pity and fear—he himself becomes an object of physical suffering. Blake shows the impossibility of Smith’s sentimental “entering into” another by making Los a failed visionary, doomed by his own sympathy and infected by the object of his pity. In terms of sentimentalism, this would correspond to acting out of sympathetic benevolence but not looking deeper into the causes of such suffering, an error that, Blake implies, drags the sympathizer farther into the miserable (fallen) system. That is, it is ineffective and essentially self-indulgent sympathy, emotion for its own sake. For Blake, as we shall see, Los’s (physical rather than visionary) response also corresponds to pitying the “vegetated” body of error that suffers rather than the spiritual individual within.21↤ 21. It is worth noting briefly here that the truly visionary “entering into” others that Los does and advocates in Blake’s later epic Jerusalem reflects the central, heroic role that he gained in Blake’s mythology from the minor Prophecies and The Four Zoas to Milton and Jerusalem. Los seems to have learned much between the epics.

Although sentimentality in The Four Zoas is a telltale sign of fallenness, Blake’s attitude at times seems ambivalent, and he is not wholly committed to exposing it as a Urizenic corruption. The deciding factor is how it is used. Further, the connection of sentimentality to the female Emanations does not automatically lead Blake to reject all forms of sentiment as pernicious. Ahania and Enion play crucial roles in the epic’s push toward regeneration precisely because of their emotional, affective, and sympathetic natures (in contrast to Enitharmon and Vala, the manipulative females). They are truly the most consistent voices calling for unity, while the males only remind them of their emanated being, wallow in helpless self-pity, or lash out in destructive wrath and war. Although these Emanations are raped, beaten, and driven to non-existence for their efforts, they are like a sentimental “glue” that keeps Albion’s fragments from separating completely. Along with the song of Enion discussed above and her first speech in Night I, in which she laments her separation from Tharmas, Ahania’s speech to Urizen in the opening of Night III is significant. Indeed, Ahania is the first character to speak of the “Eternal Brotherhood” that has been lost, and she begs Urizen to “Listen to her who loves thee lest we also are driven away” (FZ 41:9, E 328; 42:8, E 328). Urizen, of course, will have none of this, so her appeal gets her promptly cast into Non Entity. Nevertheless, as the chaos within Albion grows ever more perilous, Ahania and Enion lurk in the shadows as reminders of the real reason for the suffering that every character endures.

Interestingly, Ahania and Enion have positive roles by virtue of their relation to nature and the fallen world. While this relationship reflects the social (and sentimental) view associating the emotions and the physical body with femininity, McGann points out that “the destructive nature of nature” is also part of the Christian tradition Blake writes within (151). As a result, nature has a “redemptive mechanism”—hence the incarnation, begin page 73 | ↑ back to top the belief that the spiritual/divine is born through the corporeal body in order to redeem it. In this respect, even Enitharmon and Vala (including her most fallen forms, Rahab and Tirzah) are “positive” or “redemptive.” As Ackland notes, Enitharmon’s “realm is nature, and nature remains part of the Divine Humanity”; even “the triumph of Vala [in Night VIII; see below] can serve paradoxically as a prelude to apocalypse, for any consolidation of error makes it more readily identifiable and remediable” (180). The feminine realm of corporeality, physical emotion, and sentiment is, like the fallen body of Albion that it comprises, potentially redeemable, a stage (or even an early form of a Blakean “State”) in the regenerative process.

While McGann and Ackland are both correct in identifying the positive function of the females and nature in Blake’s myth, Ackland in particular is too prone to stress their “redemptive role” and to miss the larger point that Blake makes with his use of Emanations and a gendered, generative nature. Although he wrote poems like “On Anothers Sorrow” and chided a cold, unfeeling culture, Blake was equally aware that “Innocence” in the world is the state of childhood, not of Eternity. Consequently, fallen existence is a reality, but it is not a positive reality; it is a trap, a slumber or death of Albion and every individual that must be overcome for a return to Eternity. Again, it is all too easy in a fallen world to “become what one beholds,” to see one’s vegetative body as the real body, and to remain “dead.” In a society practicing the art of sentiment, this lapse of spiritual vision becomes even easier. Thus, sentimental pity and benevolence, however positive they may be in ameliorating fallen hardship, are not enough for regeneration in Blake’s works. For him, regeneration (poetic, personal, and universal) requires inspired vision, which the weakening and exploitative tendencies of sentimentalism, along with its reification of the physical or natural, prevent. Social misery does gain Blake’s critical attention, but, as Martin Price comments, “Blake is less concerned with exposing injustice than with finding a vital response to it” (401). In the examples I have discussed from The Four Zoas thus far, Blake has certainly exposed the problems inherent in a system of sentiment, its part in the battle between the sexes, and its use as a tool for oppression. And Ahania and Enion’s positive sentimentality does not solve these problems, for it too is a product of the fall; thus, they can only propose “facile modifications rather than fundamental changes either in the behavior of the zoas or in their own behavior” (Lee 134). The question, then, is how to move beyond the sentimental world all together.

We can answer this question by looking at the first step taken toward Eternity in The Four Zoas. This moment comes with the embrace of Los and the Spectre of Urthona in the conclusion of Night VIIa. Although Blake’s incorporation of this material late in the composition process creates many bibliographic, textual, and narrative challenges, the scene is important here because it serves as a re-vision, in both its success and its failure, of the sentimentality expressed thus far in the poem. At this point in the plot, an unprecedented event occurs after a vivid series of splits and unions and outbursts of the dead: ↤ 22. Erdman’s edition contains an error for the page numbering at this point: he prints “95 [87]” (E 367) for what should be “95 [85],” since the text is from p. 85 of the manuscript. I have silently corrected the error in subsequent citations.

But then the Spectre enterd Los’s bosom Every sigh & groanEnitharmon’s sighs and groans, as well as her tale, seem to precipitate this embrace, much as Los’s pity and tears do. The key, however, is that Los embraces the Spectre “as another Self,” perhaps implying that he sees the Spectre as a being who shares an intimate bond with him, not as an object or other whom he merely sympathizes with.23↤ 23. As Dennis Welch points out to me, the meaning of “another Self” is highly ambiguous here—is the Spectre an other self or an aspect of Los’s self? The implication of “humanizing” may also be important if we think of Albion’s status as the “Universal Humanity,” so that Los may be becoming eternally human rather than physically human; compare Tharmas in Night IX (132:36ff., E 401). These instances of ambiguity (so characteristic of Blake), along with the lateness of this added passage, may help to explain why the embrace fails to initiate regeneration directly. But the Spectre speaks as a Spectre, calling himself Los’s “real Self” (95 [85]:38, E 368) and Los a mere “form & organ of life” (86:2, E 368). Los responds furiously that he feels “a World within / Opening its gates,” and he bids the Spectre to enter his bosom with Enitharmon to learn “Peace” and “repentance to Cruelty” (86:7-12, E 368). For the first time, a male character urges action that is redemptive and regenerative—and not out of simple pity, for himself or for another, but because of something stronger “within.”

Of Enitharmon bore Urthonas Spectre on its wings

Obdurate Los felt Pity Enitharmon told the tale

Of Urthona. Los embracd the Spectre first as a brother

Then as another Self; astonishd humanizing & in tears

In Self abasement Giving up his Domineering lust

(FZ 95 [85]:26-31, E 367)22

Unfortunately, the reunion of this fragmented fragment is incomplete because (at least in part) “Enitharmon trembling fled & hid beneath Urizens tree” (FZ 87:1, E 368). After she plays the Eve to Los’s Adam and tempts him to eat the fruit of the Tree of Mystery, all three of the characters fall into helpless self-blame for the fall. But this is still a momentous occasion because Los experiences a renewal, however fleeting, of vision. Continuing with his intimations of a “World within,” he sees Enitharmon “like a shadow withering / As on the outside of Existence” and tells her to “look! behold! take comfort! / Turn inwardly thine Eyes & there behold the Lamb of God / Clothed in Luvahs robes of blood descending to redeem” (87:41-44, E 369). The rest of this scene wavers between positive and negative action, the latter most evident in Enitharmon’s fear of the Lamb of God and her desire to use the spectres of the dead as “ransoms” (98 [90]:24, E 370). But, after the ambiguous refusal of Los and Enitharmon to sacrifice their children (discussed below), Los draws Urizen out of the war raging around begin page 74 | ↑ back to top them and feels “love & not hate,” beholding Urizen as “an infant” in his hands (98 [90]:65-66, E 371). Los is now able to envision the regenerated Urizen, to perceive the spiritual body within the hoary old man who has been stirring up universal antagonism, rather than the mere corporeal form.

What this scene indicates is that sentimental sympathy is essentially stagnant without Blakean vision. When Los appropriates sentimental qualities like pity, benevolence, and a desire for reunion with his suffering counterparts, he does so on the basis of his vision of “the Lamb of God” within every individual, not just because those counterparts are miserable. He sees their shared error and the need to rectify it. His visionary moment may be fleeting, but it is truly the first indicator of a potential regeneration to come. Blake’s use in this scene of the same sentimental conventions and discourse that have caused so much trouble in the earlier Nights serves to revitalize them, for they are now a part of vision, inspiration, and prophecy—they introduce hope into a world that is still fallen and at war.

Because Los’s moment of vision in Night VIIa is powerful for the light of hope it brings into The Four Zoas, it seems fitting and yet troubling that the next Night opens with the creation of Albion’s fallen body and the descent of “the Lamb of God clothed in Luvahs robes,” i.e., Jesus the Savior in physical form (FZ 101:1, E 373). The first moment of redemptive vision by Los the Eternal Prophet serves as a catalyst, as it were, for the final consolidation of error. Although Los can “behold the Divine Vision thro the broken Gates / Of [Enitharmon’s] poor broken heart,” and Enitharmon can “see the Lamb of God upon Mount Zion,” Urizen can only see his enemy Luvah and gather forces for more war (99:15-17, E 372).24↤ 24. It seems significant here that Los beholds the divine vision through Enitharmon’s heart, again intimating that he has gained the vision necessary to see into the physical body to find the spiritual body within—and to see through that body to the divine. Enitharmon, on the other hand, sees the Lamb of God as external, outside herself (and others) at this point; only after weaving bodies for the spectres into “the Female Jerusa[le]m the holy” can she see “the Lamb of God within Jerusalems Veil” (104:1-2, E 376). Jesus comes as the “pitying one” to “Assume the dark Satanic body” and to give Albion “his vegetated body / [which is] To be cut off & separated [so] that the Spiritual body may be Reveald” (104:14, E 377; 104:13, E 377; 104:37-38, E 378), but this can only occur when human existence has reached its nadir. In other words, Jesus must suffer crucifixion by the forces of Mystery or Rahab, who is both a degenerated form of Vala (the “Dragon” that Luvah nurtured and the exemplar of a female tyrant) and the “Fruit of Urizens tree” (109 [105]:20, E 378). This crucifixion is “the triumph of Vala” (Ackland 180) and the final consolidation of error, the dead body of Jesus providing the most visible form of error possible.

Arguably, the crucifixion also largely results from the hypocritical system of sentiment (moral law) that Rahab practices and Urizen inspires. The song of the Females of Amalek, Rahab’s daughters, evidences Rahab and Urizen’s hypocritical sentimentality at its most obvious, which seems fitting in the context of this Night. “O thou poor human form O thou poor child of woe / Why dost thou wander away from Tirzah why me compell to bind thee,” the Females of Amalek sing over their bound victims, terrifying them with knives and tears (FZ 109 [105]:31-32, E 378). Their song eerily recalls Enion’s song in Night II, which makes the image of demonic, knife-wielding singers even more startling; it also heightens our awareness of how crocodile tears of pity can be frightfully hard to distinguish from true tears. Blake later punctuates this ambiguity, making such crocodile tears truly degenerative when Urizen’s pity for, and embrace of, the Shadowy Female causes him to mutate into a scaly monster (106:22ff., E 381; illustrated on page 70 of the manuscript).

Blake problematizes sentimentality once again, here in the form that the Females of Amalek give it, by directly following the song (as if the two were causally related) with the crucifixion of the Lamb of God on the Tree of Mystery, the tree of Rahab and Urizen (FZ 110 [106]:1-3, E 379). The sight is catastrophic, leaving even the newly inspired Los “despairing of Life Eternal” while Rahab glories “in Delusive feminine pomp questioning him” (110 [106]:16, E 379; 105 [113]:43, E 380). But Los struggles through his despair and persists in advocating self-recognition and repentance even to Rahab, speaking to her “with tenderness & love not uninspird” (105 [113]:44, E 380). His inspiration leads him to pity her for her error, an error that he himself shares but can now work to rectify (105 [113]:51-52, E 380). Although Rahab refuses to heed his words, his hope remains. And later, when Ahania cries out at the death around her, Enion seems to draw on Los’s hope as she comforts Ahania, her fellow sufferer, with a prophecy of the universal return to “ancient bliss” (114 [110]:28, E 385).

These positive threads woven into the vegetated fabric of Night VIII are, with the hypocritical and negative threads, all tied to sentimentalism, with Los’s tear shed for Rahab’s stubborn persistence in error and Enion’s sympathy for her companion in misery. But the proliferation of the word “vision” in these events further emphasizes the change that has occurred in that sentimentalism. “Sentimentality,” as it is now practiced by Los the inspired prophet, has in fact been remade into “vision” by being taken to a spiritual level, by piercing the vegetated body in order to sympathize with and work to redeem the trapped spiritual body.25↤ 25. This emphasis on “vision” in Night VIII combines with Blake’s increased, and to some extent disjunctive, focus on Jesus “the pitying one” in this Night to help reveal Blake’s attitudes towards sentimentalism that his July 1804 letter to Hayley makes even more problematic. Blake’s renewed Christian vision/faith seems to make him more convinced of the need for forgiveness of sins and pity for sinners, but this forgiveness and pity must be spiritual acts born from a recognition of “the Lamb of God” within each person. But the vegetated body remains, and the vegetated things in the natural world that serve as the objects of systematized sentiment have to be burned begin page 75 | ↑ back to top away like the error that they manifest. There has to be a Last Judgment. Thus, as Night IX opens, Jesus stands over Los and Enitharmon and separates “Their Spirit from their body” (FZ 117:4, E 386).26↤ 26. The fact that Jesus then disappears as an agent in Night IX, both in the text and in the drawings (he appears once, on p. 129, while Blake presents him in four large drawings in Night VIII), is significant, from an interpretational perspective, in light of what is to come. It is as if the blood and gore of Blake’s Last Judgment cannot directly incorporate the presence of the “pitying one,” however much the divine hand may be guiding what occurs. From a bibliographic perspective, this change of Jesus from visible victim/savior to a deus absconditus also seems to support Bentley when he gives the current Night VIII a later date than the greater part of Night IX (164-66); such a late date would make the centrality of Jesus in Night VIII a reflection of the increasing Christian focus in Blake’s later writings (as in Milton and Jerusalem). This separation seems to liberate and inspire Los anew, for he initiates the Last Judgment by tearing down the sun and moon, “cracking the heavens” so that the “fires of Eternity” can spread over the material universe and consume the error that has been given final form via the crucifixion (117:9-10, E 386).

Blake’s apocalypse is almost beautifully frightful in its violence, far surpassing his source in Revelation and implying just how powerful error is to him. His own prophetic wrath is unmistakable, and he often seems deliberately to target the figures that sentimentalism reified and realized in its culture. While Blake gives victims such as slaves, prisoners, and suffering families the chance to torment their oppressors in the opening melee (FZ 122:38-123:32, E 392-93), even these victims, as vestiges of fallen human life and objects of worldly pathos, have to go along with everything else. To accomplish this, the Zoas and Emanations must all join together to play their rightful roles. Although the labors of Urizen, Tharmas, and Urthona are quite striking as humanity and the fallen world get completely “reprocessed” into a feast for the Eternals, the most frightening apocalyptic image that Blake presents here is the winepresses of Luvah. To prepare the Last Vintage, the sons and daughters of Luvah dance and laugh, accompanied by various creatures around the presses, as they tread upon “the Human Grapes [that] Sing not nor dance” but instead “howl & writhe in shoals of torment in fierce flames consuming” and amidst various instruments of torture (136:5-39, E 404-05).27↤ 27. In Revelation 14:20, the winepress in John’s vision seems almost banal compared to Blake’s: “And the winepress was trodden without the city, and blood came out of the winepress, even unto the horse bridles, by the space of a thousand and six hundred furlongs.” Then, at last, with the world as we know it utterly annihilated, “the evil is all consumd” and Albion is again “Man”—regenerated, visionary, and alive with the harmony and order of the universe within him (138:22, E 406).

I have focused here on the violence of Blake’s Last Judgment and its human tinder because the apocalypse presents, I think, his ultimate revision of sentimentality and the entire movement that it fostered. Every human life—from victim to victimizer, from youth to elder—has to be trodden in the winepresses or baked in the ovens of the Zoas—and, as the feast implies, actually consumed by Eternal beings. Blake challenges us to mimic Los, to use our visionary capacity to see through the vegetated world and the (necessary) violence of its consummation in order to reveal the spiritual “World within.” Because even Los, the most inspired Zoa, fails to maintain that redemptive vision continuously and to change the system of error, something more extreme is required. Blake therefore envisions existence falling to its nadir with the crucifixion, which then must be followed by the utter transformation and redemptive consumption of those familiar objects that might otherwise elicit sympathy and prevent such a Last Judgment.

We can, I think, see the persistence of this fallen sentimentality in Los and Enitharmon’s refusal to sacrifice their children at the end of Night VIIa. Their pity for their children seems praiseworthy, especially when contrasted with the “Storgous Appetite” that leads to Orc’s binding in Night V. However, those newborn human souls that they pity in Night VIIa have to be thrown into the winepresses or sown in the ruins of the universe; even parental love is a tie to the fallen world. Their pity may be another critique of sentimentalism because, as Barker-Benfield observes, “the aggrandizement of the affectionate family and, at its heart, mothering,” were central components of sentimentalism through their cultivation of desired social affections (276). However, as he also describes, the emphasis placed on a sentimental family often led to “parental self-indulgence” and disabling sensibility instead of greater communal sentiments. Wollstonecraft speaks to this very problem when she condemns spoiling mothers who “for the sake of their own children . . . violate the most sacred duties, forgetting the common relationship that binds the whole family of earth together” (290). Admittedly, Blake is more extreme, but it seems that Los and Enitharmon are still guilty of an affection that holds them back from their Eternal places and from working for the greater good. These parents pity their children as pathetic, corporeal beings, as spectres with physical bodies; they refuse to make the sacrifice of all physical things—and of all sympathetic attachments to them—that the final Night shows is required for the regeneration of humanity.

According to Blake’s mythology, the status of the Emanations and of (sentimental) females as a whole necessitates that they become undifferentiated from their male counterparts in order to reconstitute the androgynous Zoas. Blake expresses this point in the poem’s closing lines: “Urthona is arisen in his strength no longer now / Divided from Enitharmon no longer the Spectre Los” (FZ 139:4-5, E 407). Once again whole, Urthona can forge the armor that Albion wears in the “intellectual War” of Eternity (139:8-9, E 407). But what exactly does “whole” imply for Urthona and the other Eternals in terms of the sexes, specifically the female sex? Blake does say that both Enitharmon and the male “Spectre Los” have disappeared as distinct, sexed identities. Nevertheless, here again we meet one problem of describing Eternity from the begin page 76 | ↑ back to top realm of Generation, since the “fallen” language that Blake uses is also gendered language. The masculine singular pronoun “his” in lines 4 and 8, referring to “arisen” and undivided Urthona, further casts the Eternal state as vigorous and masculine in contrast to the delusive, “feminine” lower states that have been the major arena for the poem’s action. While both of the separated sexes have apparently reunited into single androgynous beings, Blake’s masculinized language here and throughout makes it most apparent that the females have been reintegrated or re-internalized. And, as Albion tells Urizen shortly before the Last Judgment occurs, the Zoas are “Immortal” while the Emanations are simply “Regenerate” (122:12, E 391). Peter Otto thus questions the ending of The Four Zoas, which he sees as representing “a Urizenic ideal” in part because the Emanations are “now indistinguishable from their male counterparts” (337-38). However, the poem contains numerous reminders—some from the Emanations themselves—that the Emanations are emanated and hence secondary, just like the physical body they are associated with. Indeed, this “disappearance” of the female is in many ways the most telltale sign of regeneration based on Blake’s association of femininity with the entire fallen world. As a result, he makes it apparent that the Emanations have returned to their places as portions of the Zoas after the apocalypse; once this is accomplished, the Zoas can function harmoniously within Albion and Albion can rejoin the “Eternal Brotherhood.”

The re-internalization of the Emanations, with the destruction of sentimental stereotypes, is the final move that Blake makes in his re-vision of sentimental conventions and the sentimental system. This re-vision, an incorporation of passive sentimentality into active inspired vision, is by no means Blake’s central agenda in The Four Zoas, but it is as much a part of his “Dream” as it is a part of the fallen world. Sentimentality may, at its best, reduce the sting of the fall, but it can do nothing to regenerate humanity without the strength of vision to guide it. In his later prophecies and other writings, Blake emphasizes this point more explicitly against the backdrop of Eternity, as Los’s inspired mission and message come to center on pity and forgiveness of sin amidst continued sentimental, hypocritical oppression. Only through the regeneration of worldly sentimentality, which Blake seems to trace through the nine Nights of The Four Zoas, can a visionary prophet redeem the fallen world with tenderness and love that are inspired, not selfishly or superficially pitying, not tools for manipulation. As Blake puts it in terms of his mythology, “Tharmas gave his Power to Los Urthona gave his strength” (FZ 111 [107]:31, E 383).

Bibliography

Ackland, Michael. “The Embattled Sexes: Blake’s Debt to Wollstonecraft in The Four Zoas.” Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly 16.3 (winter 1982-83): 172-83.

Aers, David. “Blake: Sex, Society and Ideology.” Romanticism and Ideology: Studies in English Writing 1765-1830. Eds. David Aers, Jonathan Cook, and David Punter. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1981. 27-43.

—. “William Blake and the Dialectics of Sex.” ELH 44 (fall 1977): 500-14.

Allen, Richard O. “If You Have Tears: Sentimentalism as Soft Romanticism.” Genre 8.2 (June 1975): 119-45.

Ault, Donald. Narrative Unbound: Re-Visioning William Blake’s The Four Zoas. Barrytown, NY: Station Hill P, 1987.

Barker-Benfield, G. J. The Culture of Sensibility: Sex and Society in Eighteenth-Century Britain. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1992.

Bentley, G. E., Jr., ed. William Blake: Vala or The Four Zoas: A Facsimile of the Manuscript, a Transcript of the Poem and a Study of Its Growth and Significance. Oxford: Clarendon P, 1963.