article

“I also beg Mr Blakes acceptance of my wearing

apparel”

The Will of Henry Banes, Landlord of 3 Fountain

Court, Strand, the Last Residence of William and Catherine Blake

Henry Banes was the brother-in-law of William and Catherine Blake as well as their landlord at 3 Fountain Court, Strand, from 1821 until 1827.*↤ * The first two sections of this paper derive largely from chapter 3 of my MA dissertation “‘My Present Precincts’: A Recreation of the Last Living and Working Space of William Blake: 3 Fountain Court, Strand 1821-7,” MA in Blake and the Age of Revolution, University of York, October 2002, directed by Michael Phillips. I am grateful to G. E. Bentley, Jr., for generously sharing his own findings concerning Henry Banes. I also wish to thank Michael Phillips and Keri Davies for reading and commenting so helpfully on earlier drafts of this paper. Finally thanks to John Barrell, Robert Essick, Sarah Jones, David Linnell, Angela Roche and David Worrall for advice on minute particulars. This paper will focus primarily upon the contents of Henry Banes’ will, a document hitherto unknown to Blake scholarship.1↤ 1. Although the original will written by Henry Banes has not been traced, the Prerogative Court of Canterbury probate copy has (see below). As well as explicitly referring to, and providing new information about, William and Catherine Blake, Banes’ will throws new light on the Blakes’ relationship with their relative and landlord. The will also contains information pertinent to a clearer understanding of Catherine Blake’s financial affairs and how and where she was living in the spring of 1829, approximately eighteen months after the death of her husband. In addition, the document provides the dates of the decease of Henry Banes and his wife, Catherine Blake’s sister, Sarah Banes, and evidence of Sarah’s residence at 3 Fountain Court from 1803 until March 1824. Sarah’s established presence at this address may partially explain William and Catherine Blake’s choice of residence on removal from their apartment at 17 South Molton Street in 1821.

It has been previously assumed that, apart from Blake’s younger sister, Catherine Elizabeth Blake, William and Catherine Blake had no surviving family relations. I will argue that the circumstances surrounding Banes’ choice of “sole Executrix” of his will suggest that Henry and Sarah Banes may have had a daughter and therefore that William and Catherine Blake may have been survived by a niece, named Louisa (or Louiza) Best, née Banes.2↤ 2. “Louisa” is the spelling used in the 1841 census return for 3 Fountain Court, Strand (Public Record Office HO 107/731/3 15). “Louiza” is the spelling used in the PCC copy of the will of Henry Banes, proved 14 February 1829 (PRO PROB 11/1751 [Liverpool Quire 51-100, folio 79]). Finally, the sole witness of Henry Banes’ will, the artist John Barrow, will be conclusively identified as the publisher of Blake’s commercial engraving “Mrs Q” (1820).

Henry Banes, William and Catherine Blake’s Relation and Landlord

In about 1860, Blake’s biographer, the 32-year-old Alexander Gilchrist, visited Fountain Court, on the south side of the Strand, in order to research William and Catherine Blake’s last residence. At 3 Fountain Court Gilchrist encountered a “dirty stuccoed” building that had “suffered a decline of fortune”3↤ 3. Gilchrist 282. (illus. 1). The front room on the first floor, the Blakes’ former reception room, showroom and printing studio, was vacant and “in the market at four and sixpence a week, as an assiduous enquirer found.”4↤ 4. Gilchrist 282. The rest of the house was “let out . . . in single rooms to the labouring poor.”5↤ 5. Gilchrist 282. During his visit, Gilchrist could have encountered a number of the 36 inhabitants recorded in the 1861 census return for 3 Fountain Court. Amidst the “excessive noise of children,”6↤ 6. Gilchrist 308. he may have called on and conversed with William Jones, wine porter, George Caudle, vellum binder, Mary Huntley, laundress, James Stone, onion dealer, William Wilby, police constable, William Jones, carman, James Haywood, fishmonger, and Thomas Curtis, water gilder, and their respective families.7↤ 7. 1861 census [7 April 1861] return for 3 Fountain Court, Strand, PRO RG 9/179/68. However, it seems unlikely that anyone then living either at this residence or elsewhere in Fountain Court had been a fellow lodger or neighbor of William and Catherine Blake over 30 years earlier.

Few details concerning, or indeed derived from, those “humble but respectable”8↤ 8. Gilchrist 308. former neighbors of the Blakes were included in Gilchrist’s Life of William Blake, published posthumously in 1863.9↤ 9. Gilchrist does refer to a “humble female neighbour, [Catherine Blake’s] only other companion” present at Blake’s death who “said afterwards: ‘I have been at the death, not of a man, but of a blessed angel’” (Gilchrist 353). The neighbor’s description of Blake’s death resembles a line in Sydney Cumberland’s letter to his father George Cumberland c. November 1827 in which he reports that Catherine Blake told his brother George that Blake “died like an angel” (BL Add. MSS. 36512, ff. 52-53, n.d., cited Bentley, Blake Records [hereafter referred to as BR (2)] 475). Had such figures been traced, their accounts might have complemented those of the less materially humble figures that Gilchrist did interview or correspond with concerning Blake’s last years, including John Linnell, Samuel Palmer and Frederick Tatham. Indeed, few of the 20 or so biographies of William Blake published between 1893 and 2001 have enhanced our knowledge and understanding of what the Blakes did and whom they associated with begin page 79 | ↑ back to top

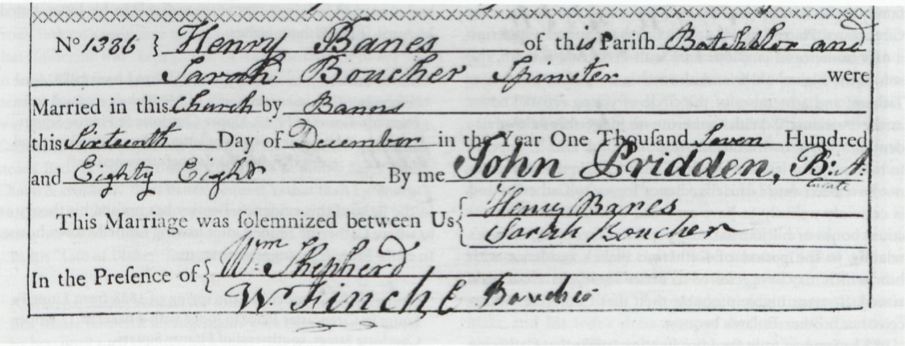

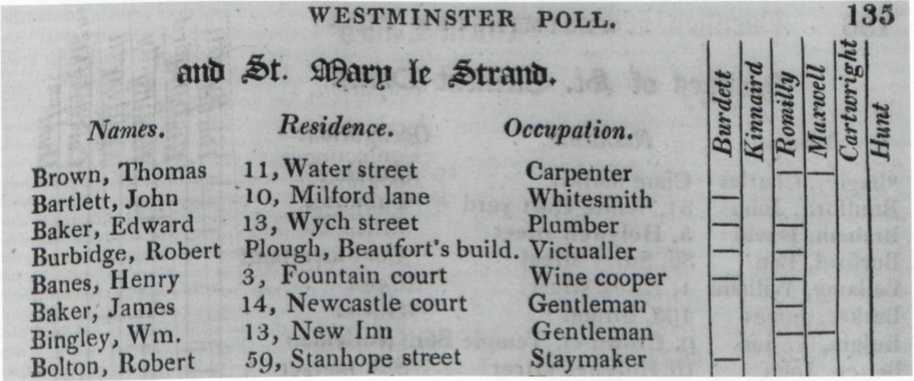

One fellow resident well placed to throw light on the Blakes’ life and work during this period is Henry Banes, William and Catherine Blake’s brother-in-law and landlord at 3 Fountain Court. However, few biographers of William Blake have succeeded in tracing more than Banes’ name. In a letter to the Quaker poet Bernard Barton of 3 April 1830, John Linnell, Blake’s friend and patron during the 1820s, describes William and Catherine Blake’s last shared residence as “a private House Kept by Mr Banes whose wife was sister to Mrs Blake.”13↤ 13. Cited BR (2) 526-27. Frederick Tatham in his ms. “Life of Blake” (c. 1832) refers to Henry Banes as Blake’s “Wifes brother” (cited BR [2] 680). As Ruthven Todd observes: “presumably this is an error for brother-in-law” (Gilchrist 389). Linnell’s only other recorded reference to Henry Banes is found in the final line of a “Note by J[ohn]. L[innell]. sen[ior]. on strip of paper” “1855?”, transcribed by Linnell’s son John Linnell, Jr. Bentley describes this note as “clearly the heads of what Linnell meant to tell Gilchrist of Blake’s life.”14↤ 14. BR (2) 430fn. The line reads “[Blake] died at his Brother in Laws first floor 3 F[ountain] Court[.]”15↤ 15. BR (2) 430fn. Beyond this “head” Linnell does not appear to have provided Gilchrist with any further information concerning Blake’s last landlord. Gilchrist’s allusion to Banes in a description of Blake’s final residence as “a house kept by a brother-in-law named Baines [sic]”16↤ 16. Gilchrist 282. Gilchrist almost certainly received this information from John Linnell. Between 1803 and 1822 the Poor Rate collectors responsible for Fountain Court consistently recorded Henry Banes’ surname as “Baines” in their rate books (see illus. 2). However, Banes’ marriage record (illus. 7), the only traced document to feature his signature, entries in contemporary trade directories (illus. 4) and poll books (illus. 3), as well as Banes’ own will (illus. 5) all suggest that “Banes” is the correct spelling. merely reiterates Linnell’s two statements cited above.

Since Gilchrist, few further details concerning Henry Banes have been traced. Almost a century after the publication of Gilchrist’s Life, Paul Miner consulted the Poor Rate books for the parish of St. Clement Danes and discovered that “‘Henry Baines’ or ‘Banes’ . . . is listed [as ratepayer] for the house [i.e., 3 Fountain Court] during the period of Blake’s occupancy.”17↤ 17. Paul Miner, “William Blake’s London Residences,” Bulletin of the New York Public Library 62.11 (November 1958): 544. In his recent biography of Blake, The Stranger from Paradise (2001), Bentley offers a little more information concerning Henry Banes. The biography features a reconstruction of the Boucher family tree in which Sarah Boucher is first identified as the sister of Catherine Blake who married Henry Banes. The location and date of the marriage are given as St. Bride’s Church, Fleet Street, 10 November 1788.18↤ 18. Bentley, Stranger xx. Bentley also records the location (but not the date) of Henry Banes’ baptism, also in the parish of St. Bride.19↤ 19. Presumably Bentley assumed that St. Bride’s, Fleet Street, the parish in which Banes married, was also the parish of his baptism. However, FamilySearch, the records of the International Genealogical Index available online <http://www.familysearch.org>, contains no record of a Henry Banes baptized at St. Bride’s, Fleet Street. Bentley’s assertions concerning the date and location of Banes’ burial are, as will be demonstrated below, mistaken. In addition, Henry Banes’ place of begin page 80 | ↑ back to top burial is given as “St Andrews, Holborn” and the year of his death as 1837.20↤ 20. See Bentley, Stranger xx. Bentley cites the second edition of Blake Records as the source of this information (Stranger xix). In Blake Records, Bentley states that “Henry Bain (not Baines) was buried in St Andrew’s Church, Holborn, in 1837, according to Boyd’s Burial Index in Guildhall” (BR [2] 50fn). As I demonstrate below, Henry Bain (actually buried at Bunhill Fields) cannot have been Blake’s landlord at Fountain Court. Boyd’s Burial Index is an unpublished index of London and Middlesex burials in parish register transcripts, compiled by Percival Boyd (1866-1955). Boyd only indexed burial registers which had been transcribed and were easily accessible. With the help of the College of Arms, Boyd copied about a quarter of a million burials between 1538 and 1852, including a large part of the registers of Bunhill Fields nonconformist burial ground. See Anthony Camp, “Our Greatest Indexer—Percival Boyd,” Practical Family History no. 72 (December 2003): 22-24. In the introduction to his Burial Index Boyd remarks, “Those who use this index are warned that it must be treated as a ‘lucky dip,’ if you find what you want, well & good; if you dont [sic], you have searched nothing.” I am indebted to Valerie Hart, Reference Librarian, Guildhall, for this information. The only other reference to Henry and Sarah Banes in The Stranger from Paradise occurs on 392, where Bentley cites the passage from Linnell’s letter of 3 April 1830, discussed above. In the second edition of Blake Records, Bentley gives the (correct) date of Henry Banes and Sarah Boucher’s marriage as 16 December 1788, as well as details concerning the banns, the curate who performed the marriage and the identity of one of the three witnesses.21↤ 21. BR (2) 751fn. See also BR (2) 49-50. However, the mistake is replicated in the Boucher-Butcher genealogy, BR (2) xxxiv. Bentley also expands upon Miner’s findings concerning the identity of the ratepayers for the property: “The Rate Books confirm that the rate-payers were Henry and Mary Baines (or Banes) from 1820 to 1829.”22↤ 22. BR (2) 751. Bentley explains in a footnote that the rate books for St. Clement Danes, Savoy Ward, recorded: “Henry Ba[i]nes for 1820-22, 1826-28; Mary Banes for 1823; and both for 1824 and 1825” (BR [2] 751fn). Bentley goes on to state that in the Poor Rate books 3 Fountain Court “is specifically called a ‘House’ to distinguish it from the warehouses in the area . . .” (BR [2] 751fn). This does not appear to have been the case and would not have been necessary, as the 16 residences in Fountain Court were separated from the warehouses of Beaufort Wharfs by a flight of stairs. See Whitehead illus. 1 and 8. In an attempt to reconcile the discrepancy between the first names given to Banes’ wife in the marriage certificate of 1788 and the rate book entries almost forty years later, Bentley suggests that “Perhaps Catherine’s sister Sarah Boucher . . . was also called ‘Mary’ after her mother, Mary Davis Boucher.”23↤ 23. BR (2) 751fn.

A letter from Blake to John Linnell recently discovered by Michael Phillips provides the sole recorded reference to Henry Banes by Blake.24↤ 24. For discussion of the letter, see Phillips, Whitehead 27-28, Bentley, “William Blake and His Circle” 5, 10-11, 32. The letter, postmarked “25 · NO 1825”, begins:

Mr Banes says his Kitchen is at our service to do as we please. Still I should like to know from the Printer whether our own Kitchen would not be equally or even more convenient as the Press being already there would save a good deal of time & trouble in taking down & putting up which is no slight job [cited Phillips 140].Phillips demonstrates that the new letter refers to preparations for a specially organized printing session of the Illustrations of the Book of Job using Blake’s rolling press at 3 Fountain Court. The printing session was to be conducted by a fine art plate-printer, an employee of the copperplate printer James Lahee, and overseen by Blake and perhaps Linnell. It must have taken place in late November-early December 1825, immediately after the engraving and final proofing of the plates and immediately before the printing of the 315 sets of the Illustrations of the Book of Job at Lahee’s premises at No. 30 Castle Street East, Oxford Market. As Phillips observes: ↤ 25. Phillips 153.

It was now the moment to confer with Lahee’s plate-printer to supervise with him the printing of master impressions for each of the 22 plates. The plate-printer would then be able to return to the Castle Street works and left to get on with it.25This printing session, lasting no longer than a few days, would normally have been conducted at Lahee’s Castle Street works. However, as Blake was evidently incapacitated by illness at this time and therefore unable to travel so far, 3 Fountain Court was proposed as an alternative location. Banes’ “Kitchen” in the basement of 3 Fountain Court, as opposed to Blake’s printing studio in the front room on the first floor, appears to have been proposed by Linnell as the most suitable area of the house in which to conduct the printing session. As Blake’s letter indicates, Banes readily agreed to this proposal. However, due to the considerable technical difficulties involved in dismantling Blake’s printing press, moving it from the Blakes’ front room to Banes’ basement and reassembling it there (which Blake describes as “no slight job”), the press almost certainly remained where it was. Therefore, in the event, it seems that Banes’ basement was never utilized as a temporary printing studio (see Phillips). Nevertheless, as Bentley suggests, the fact that Banes was willing to give up his kitchen to accommodate his brother-in-law’s printing shows that “The relationship of Henry Banes and William Blake was clearly a friendly one.”26↤ 26. Bentley, “William Blake and His Circle” 5.

New Information Concerning Henry Banes

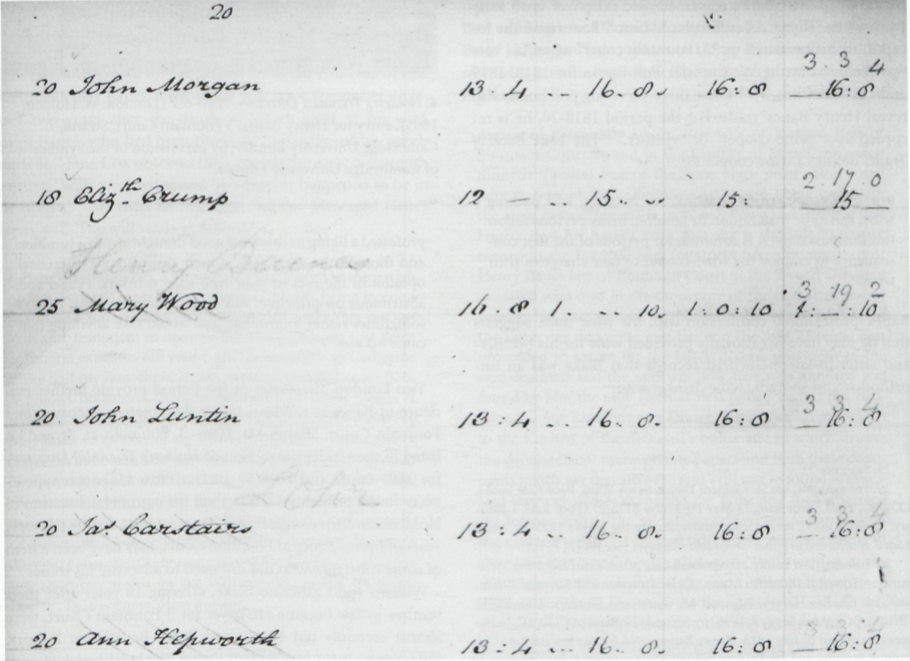

The entries for 3 Fountain Court, Strand, contained in the Poor Rate books for the parish of St. Clement Danes, Savoy Ward, reveal that Henry Banes was the sole recorded ratepayer for the property from May 1803, when his name replaced that of “Mary Wood” (see illus. 2).27↤ 27. Poor Rate book for St. Clement Danes Parish, Savoy Ward, 1803, City of Westminster Archives Centre (hereafter referred to as COWAC), microfilm B224. 1803 is of course the year William and Catherine Blake returned from Felpham to London, and then to their lodgings on the first or second floor of 17 South Molton Street. Perhaps Blake visited Henry and Sarah Banes at their new residence in 1803-04 while passing through the Strand. See Blake’s letters to Hayley, 26 October 1803 (Erdman [hereafter cited as “E” followed by page number] 738), 29 September 1804 (E 755). With the exception of the begin page 81 | ↑ back to top

a person employed in drawing off, bottling, and packing wine, spirits or malt liquor. In London, many persons follow this business only; it is common for persons of the first consequence to employ the wine-cooper to take charge of their wines.32Banes’ professional connection with the wine trade suggests that he may have occasionally provided wine for his brother- and sister-in-law.33↤ 33. It seems most likely that Banes, as landlord of the property, occupied the ground and basement floors of the house (see Dan Cruickshank and Neil Barton, Life in the Georgian City [London: Viking, 1991] 53-62). Gilchrist records that Blake was an unorthodox and sporadic wine drinker who:

professed a liking to drink off good draughts from a tumbler, and thought the wine glass system absurd: a very heretical opinion in the eyes of your true wine drinkers. Frugal and abstemious on principle, and for pecuniary reasons, he was sometimes rather imprudent, and would take anything that came his way.34

Two London directories of the period provide further evidence of Banes as resident, rather than merely ratepayer, at 3 Fountain Court. “Banes Mr. Hen. 3, Fountain-ct. Strand” is listed in the residential section of Holden’s Triennial Directory for 1805-06-07 and 1808-09-10 (see illus. 4).35↤ 35. Holden’s Triennial Directory, 1805-6-7 (London: W. Holden, 1805) n. pag., and 1808-9-10 (London: W. Holden, 1808) n. pag. The 1808 edition appears to be a reprint of the 1805 edition. Such appearances in the residential rather than the commercial section of Holden’s directory suggest that Banes, at least during the early years of his residence at Fountain Court, may have been a man of some substance who did not need to advertise his trade.

William and Catherine Blake, arriving 18 years after their brother-in-law became ratepayer for 3 Fountain Court, were almost certainly not Henry and Sarah Banes’ first lodgers. Burial records for St. Clement Danes, the local parish church of the inhabitants of Fountain Court, Strand, reveal evidence which suggests that at least one other family was lodging with Henry and Sarah Banes before the Blakes’ arrival. According to these records, a Martha Walker, recorded as resident at 3 Fountain Court, was buried aged three weeks in the churchyard of St. Clement Danes, Strand, on 8 January 1816.36↤ 36. Burial register of St. Clement Danes, Strand, COWAC, SCD 16, burial no. 1042. Although I have discovered no information concerning Martha’s parents, it seems likely that they were lodgers at Henry and Sarah Banes’ house in early 1816.

begin page 83 | ↑ back to topHenry Banes’ Will

A transcription of Henry Banes’ will has recently come to light (see illus. 5 and 6).37↤ 37. The document, made by a clerk at the Prerogative Court of Canterbury, Doctor’s Commons, for the court’s registers (PRO PROB 11/1751, Records of the Prerogative Court of Canterbury, Prerogative Court of Canterbury and related probate jurisdictions: will registers, Liverpool Quire Numbers 51-100), was consulted at the National Archives, Kew. The fact that Banes left a will that was proved by the Prerogative Court of Canterbury suggests that he was a comparatively prosperous individual at the time of his death. However, according to the Probate Act book for [February] 1829, Banes’ estate was valued at just £100. “Henry Banes—On the fourteenth day the will of Henry Banes late of Fountain Court, Strand in the Parish of Saint Clement Danes in the Parish of Middlesex deceased was proved by the Oath of Louiza Best (wife of Richard Best) the sole Executrix to whom Administration was granted having been first sworn duly to administer. £100 Resworn at the Stamp Office 14th June 1830 Under £200” (PRO PROB 8/222 [14 February 1829]). It is clear from the contents of this document that Banes rewrote his will on 9 December 1826, over two years after the death in March 1824 of his wife, Sarah Banes, who had been the “sole Executrix” of his previous will.38↤ 38. It is possible that Henry Crabb Robinson’s visit to 3 Fountain Court two days earlier, during which Robinson informed Blake of the death of his friend, the sculptor John Flaxman (see BR [2] 452-53), may have prompted Banes to rewrite his will. Jane Cox observes that, during the early nineteenth century, “wills were witnessed by whoever happened to be in the house.”39↤ 39. Cox 24. An artist named John Barrow witnessed Henry Banes’ will. The will reads as follows: ↤ 40. Italics indicate that this sentence is an insertion by Banes. ↤ 41. I have underlined this section to indicate a deletion (crossing out) by Banes.

I, Henry Banes of No. 3 ffountain Court Strand in the parish of St. Clement Danes in the county of Middx being in good health and sound mind and memory do make this my last Will and Testament in manner following after my just debts & funeral expenses are paid I give & bequeath to Catherine Blake half my household goods consisting of Bedsteads Beds & pillows Bolsters & sheets & pillow Cases Tables Chairs & crockery & £20 in lawful money of Great Britain I also beg Mr Blakes acceptance of my wearing apparel40—I also give & bequeath to Louiza Best the remaining part of my household goods as aforesaid with the Clock & my Watch & silver plate. (& pictures what is worth her acceptance)41 and all the remainder of my property in money & outstanding debts of whatever nature or description for her whole and sole use or disposal I also constitute and appoint the said Louiza Best my sole Executrix of this my last Will and Testament—H. Banes Decr 9th 1826 witness John Barrow.Henry Banes died on 20 January 1829. Just over a fortnight later, on 6 February 1829, Louisa Best and her son Thomas gave their testimonies under oath as to the authenticity of the will at the Prerogative Court of Canterbury at Doctor’s Commons, near St. Paul’s. A week later, on 13 February, Thomas Best returned to Doctor’s Commons, accompanied by the Bests’ lodger and sole witness to Henry Banes’ will, John Barrow, who gave his testimony. The will was proved the following day.

Appeared Personally Louiza Best wife of Richard Best of ffountain Court Strand in the County of Middlesex watch ffinisher Thomas Best of the same place print colorer and John Barrow of the same place artist and being sworn on the Holy Evangelists made oath as follows and first the said Louiza Best for herself saith that she is the sole Executrix named in the last Will and Testament hereunto annexed of Henry Banes late of ffountain Court in the Strand aforesaid deceased who died in the mourning of the twentieth day of January last past and she further saith that in the evening of the same day deponent and her son the said Thomas Best proceeded to search for the last Will and Testament of the said deceased and the said will now hereunto annexed was found by him the said Thomas Best folded up but not contained in any Envelope in a Drawer (which was kept locked) in the Kitchen of the deceased’s house and in which drawer the deceased kept many private papers and both these deponents jointly say that after the said Will was so found as aforesaid they perused & examined the same and then observed the former Will of the said deceased written at the back of the said last will to be crossed thro with a pen in manner as the same now appears with the word “Will” written at the foot therof and the deponent the said Louiza Best for herself lastly saith that Sarah Banes the deceaseds wife and the sole Executrix and Legatee named in the said former Will of the deceased died in the Month of March in the year one thousand eight hundred and twenty four and the deponents the said Thomas Best and John Barrow for themselves jointly say that they knew and were well acquainted with the said Henry Banes deceased for several years before and down to the time of his death and also with his manner and character of handwriting and subscription having often seen him write and subscribe his name and having now carefully viewed and perused the said last Will and Testament of the said deceased the same beginning thus “I Henry Banes of No 3 ffountain Court Strand in the parish of Saint Clement Danes in the county of Middlx” ending thus “I also constitute the said Louiza Best my sole Executrix of this my last Will & Testament” and thus subscribed “H Banes” and dated Decr 9th 1820 [sic] and having also particularly noticed the interlineation of the words “I also beg Mr Blakes acceptance of my wearing apparel” between the 10th and 11th lines and the words “& silver plate” between the 13th and 14th lines of the said will they the deponents lastly saith that they do verify and in their consciences believe the whole body [illeg.] and contents of the said will and the said writen[?] interlineations respectively as well as the said subscription to the said will to be all of the proper handwriting and subscription of the said Henry Banes deceased—Louiza Best—Thomas Best. on the sixth day of ffebruary 1829 the said Louiza Best (wife of Richard Best) and Thomas Best were duly sworn to the truth of this affidavit before me John Danberry Surr. Prest.[?] John Box not. pub. On the 13th day of ffebruary 1829 the said Thomas Best was begin page 84 | ↑ back to top begin page 85 | ↑ back to topbegin page 86 | ↑ back to top resworn and the said John Barrow duly sworn to the truth of this affidavit the several alterations appearing therein having been first made Before me John Danberry Surr. Prest.[?], John S. Glennie not. pub.

PROVED at London 14th ffebruary 1829 before the worshipful John Danberry Doctor of Laws and Surrogate by the oath of Louiza Best (wife of Richard Best) the sole Executrix to whom admon was granted having been first sworn duly to administer

The Death of Sarah Banes, née Boucher, and the Identity of “Mary Banes”

As observed above, Henry Banes married Catherine Blake’s sister, Sarah Boucher, at St. Bride’s Church, Fleet Street, in late 1788.42↤ 42. See BR (2) 49. The marriage register for the parish of St. Bride confirms that Henry Banes, bachelor, married Sarah Boucher, spinster, in this parish on 16 December 1788 (see illus. 7).43↤ 43. Guildhall Library Ms 6542/2, 1386. As Bentley observes, the curate of St. Bride’s, John Pridden, officiated at the ceremony (see BR [2] 49). Pridden’s father was a bookseller in Fleet Street. As well as performing his clerical duties, Pridden was also an antiquary, amateur artist and architect (see Alumni Cantabrigiensis Part 2, 1752-1900, vol. 5 [Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1953] 197). The banns for the marriage of Henry and Sarah Banes were read on the three preceding Sundays: 30 November, 7 December and 14 December 1788 (Guildhall Library Ms 6544/4). The witnesses were William Shepherd, W. Finch and E. Boucher. As Bentley suggests, E. Boucher is almost certainly Sarah’s sister, Elizabeth Boucher (1747-91) (see Bentley, Stranger 63fn, BR [2] 50). The signatures of William Shepherd and W. Finch as witnesses at other weddings at St. Bride’s suggest that they were parish or church officials rather than friends or relatives of the couple. See, for example, the marriage record for William Meredith and Hannah Price, 1 December 1788 (Guildhall Library Ms 6542/2, 1383). Indeed, in the record of the baptism of William Shepherd and his wife Elizabeth’s son, Joseph Gardner Shepherd, St. Bride’s, 20 December 1789, William’s occupation is recorded as “parish clerk” (see St. Bride’s baptismal register, Guildhall Library Ms 6541/2). With Sarah Banes, née Boucher, conclusively identified as Banes’ wife, it is puzzling that a “Mary Banes” rather than a “Sarah Banes” is recorded as sole ratepayer, and therefore the Blakes’ landlady, at 3 Fountain Court for 1823 and co-ratepayer with Henry Banes for 1824-25.44↤ 44. COWAC, B246-48. Bentley has suggested that “Mary” may have been a name Sarah Banes was familiarly known by.45↤ 45. BR (2) 751fn. However, at the proving of Banes’ will, his legatee and “sole Executrix” Louisa Best testified that Sarah Banes died in March 1824, a year before “Mary Banes” is last recorded as ratepayer for the residence. Such evidence initially suggests that Sarah and “Mary Banes” are unlikely to have been one and the same person. However, the appearance of “Mary Banes” in the Poor Rate book in 1825, a year after Sarah Banes’ death, may have been due to a failure by the Poor Rate collector to amend his entry for 3 Fountain Court, Strand, in the ledger for that year. After 1825, “Mary Banes” does not reappear in the Poor Rate book entries for 3 Fountain Court. Nor is “Mary” named as a beneficiary or executrix in Henry Banes’ will, written in 1826. Therefore, “Mary” may indeed have been the name Sarah Banes was familiarly known by.46↤ 46. Conversely, perhaps a relation of Henry Banes named Mary Banes may have lived at 3 Fountain Court and have left or died between her last appearance in the Poor Rate book on 6 October 1825 and Henry Banes’ composition of his new will on 9 December 1826.

The discovery that Catherine Blake’s sister, Sarah Banes, was a fellow resident with William and Catherine at 3 Fountain Court from 1821 until her death in March 1824 suggests that Sarah’s presence may have been a consideration in the Blakes’ choice of residence on leaving 17 South Molton Street. Perhaps Sarah, then in her mid-60s, was ill and therefore welcomed her younger sister Catherine’s company and care. Three years later, Sarah’s death may very well have altered living arrangements at 3 Fountain Court. It is possible that after March 1824, William and Catherine Blake and Henry Banes, widower, spent more time in each other’s company. As the new letter reveals, the Banes’ and the Blakes’ use of their respective living spaces at 3 Fountain Court may have been considerably more fluid than previously realized.47↤ 47. See Whitehead 27-28; Phillips 138-42. The wording of his will suggests that Banes had few, if any, other living relatives. His significant bequest to Catherine, and the wording of his legacy to Blake at the time of the writing of his will in late 1826, “I beg Mr Blakes acceptance . . .,” suggest a cordial relationship between Henry Banes and his brother-and sister-in-law. It is also likely that, from the spring of 1824 onwards, Banes, as a widower, required less personal living space and could therefore have invited other households to lodge at his house.48↤ 48. See Samuel Calvert’s anecdote concerning his father, the “Ancient” Edward Calvert, which suggests that another lodger occupied the floor above William and Catherine Blake at 3 Fountain Court (cited BR [2] 438-39). Calvert’s anecdote refers to an incident that must almost certainly have occurred after Sarah Banes’ death, as his father is unlikely to have met Blake before late 1824 (see Lister 10). Bentley suggests that the incident may have occurred during “the winter of [i.e., between February and March] 1826” (BR [2] 438).

The Death of Henry Banes and His Bequest to Catherine Blake

In The Stranger from Paradise, Bentley claims that Henry Banes died in 1837.49↤ 49. Bentley, Stranger xx. See also BR (2) xxxiv, 50fn, 884. However, Banes’ will now makes clear that he died almost a decade earlier, on the morning of Tuesday 20 January 1829.50↤ 50. Although we now know the date and location of Banes’ death, both the date and location of his burial remain elusive. There is no record of the burial of a Henry Banes during late January to early February 1829 in the burial registers of Bunhill Fields or the parishes of St. Bride, Fleet Street (where Banes was married), St. Andrew, Holborn (the burial place claimed by Bentley), St. Clement Danes (the parish church for Fountain Court, Strand), St. George, Hanover Square, St. Anne, St. Martin-in-the-Fields, St. Mary-le-Strand, St. James, Piccadilly, St. Paul, Covent Garden or St. Margaret, Westminster. Both Catherine and William Blake, begin page 87 | ↑ back to top

In his will, Henry Banes wrote: “I give & bequeath to Catherine Blake half my household goods consisting of Bedsteads Beds & pillows Bolsters & sheets & pillow cases Tables Chairs & crockery & £20 in lawful money of Great Britain.” During the four years of her widowhood, Catherine enjoyed the material support of several of her late husband’s friends. She also derived some income from the sale of items from her remaining stock of her husband’s works.52↤ 52. In addition, Blake’s painting and printing materials were almost certainly still in Catherine’s possession. Catherine may also have retained Blake’s domestic copperplate rolling press. According to Linnell’s journal, the press arrived at his residence at 6 Cirencester Place on 30 August 1827. Catherine followed on 11 September (see BR [2] 468, 471). It is unclear whether the press accompanied Catherine when she moved to Frederick Tatham’s residence in the late spring of 1828. Much of her furniture appears to have been sold at this time (see BR [2] 791). This may have been because Tatham did not have as much space available for Catherine and her possessions as Linnell had had at his residence. If Catherine’s press was also sold by Linnell in 1828, Tatham, in his printing of posthumous copies of Blake’s illuminated books such as Jerusalem copies H, I and J (c. 1832), may have used another press such as, perhaps, that of fellow “Ancient” Edward Calvert. See Lister 24. Nevertheless, Banes’ bequest to Catherine is materially significant. In the spring of 1829, such a legacy would have been welcome to a widow whose financial situation at that time would almost certainly have been modest, perhaps even precarious.53↤ 53. In terms of his bequest, Henry Banes appears to have been comparatively generous towards his sister-in-law. However, one wonders why Catherine left 3 Fountain Court, Banes’ house and her home for approximately six and a half years, on 11 September 1827, only a month after her husband’s decease (see BR [2] 471). Perhaps Banes could not afford to have Catherine occupy the best floor of the house rent-free. However, did Catherine Blake receive Banes’ bequest? No record of Catherine’s inheriting a portion of her brother-in-law’s estate has been traced. This is not altogether surprising. Most surviving records relating to Catherine Blake’s financial circumstances in the period from her husband’s death in August 1827 to her own death in October 1831 derive from the account books of John Linnell. After Blake’s death, Linnell both bought, and helped Catherine to sell, a number of those of her husband’s works still in her possession.54↤ 54. See BR (2) 474-88, 504, 790-93.

In September 1827, a month after Blake’s death, Linnell also provided a home and employment (as housekeeper) for Catherine.55↤ 55. BR (2) 754. This arrangement came to an end in the late spring of 1828, when Linnell sold his town residence and studio at 6 Cirencester Place, Fitzroy Square, and moved with his begin page 88 | ↑ back to top family to 26 Porchester Terrace, Bayswater.56↤ 56. Story 1:248; David Linnell 116. Before vacating Cirencester Place, Linnell appears to have found Catherine a new home (and employment) with Frederick Tatham, the son of the Blakes’ old friend, the architect Charles Heathcote Tatham, and a member of the circle of young artists known as the “Ancients.”57↤ 57. David Linnell 116. David Linnell does not cite a source for this information. However, in response to my query, he replied “The meeting between F. Tatham and Linnell is recorded in Linnell’s journal. 29th March 1828 . . . ‘Mr. F. Tatham dined at Hampstead’. Mrs Blake’s move is not mentioned . . . But as Linnell was getting rid of Cirencester Place and needed Mrs Blake to move out it is reasonable to assume that this was discussed over dinner—especially as she moved to live with Tatham” (email, 15 March 2005). David Linnell has also suggested that if Catherine had moved into independent lodgings on leaving Cirencester Place, Linnell would almost certainly have helped with her rent (email 17 March 2005). No such payments are recorded in Linnell’s account book entries for the period 1828-30 (see BR [2] 791-93). With Catherine no longer his fellow resident, employee or immediate responsibility, Linnell appears to have played a less active role in her life.58↤ 58. In his journal, Linnell records a visit to Catherine Blake on 19 September 1828, almost six months after she had left Cirencester Place (see BR [2] 488). His next recorded visit took place on 27 January 1829, when Catherine told him “that Mr Blake told her he thought I shd pay 3 gs. a piece for the Plates of Dante—” (BR [2] 493). On 3 March 1830, Linnell accompanied Haviland Burke to Catherine’s residence in order to purchase “two Drawings 8 gs. two Prints of Job & Ezekiel 2 gs & the colord Copy of the Songs of Innocence & Experience making 20 gs” for John Jebb, Bishop of Limerick (see BR [2] 509). According to Bentley, Linnell also called on Catherine on 3 August and 3 September 1830 (see BR [2] 534). However, on checking the relevant volume of Linnell’s journal (collection of the Manuscripts Department of the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, MS 8-2000), Nicholas Robinson, Curator of Manuscripts at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, could find no entry referring to Linnell’s visiting Catherine on 3 August 1830 (email 5 April 2005). By early 1831, as Bentley observes, “Catherine had become suspicious and mistrustful of Linnell’s motives” (BR [2] 537). There is no record of John Linnell and Catherine Blake’s meeting again before her death on 18 October 1831. However, Linnell records payments to Catherine in April, 6 July (via Tatham), 16 September 1828 (via Tatham); 26 January (for drawings by Blake and Fuseli), 15 May 1829 (via Tatham for “Homer’s Illiad & Oddessey Trans by Chapman”); 25 August 1831 (for copies of Blake’s Poetical Sketches and Descriptive Catalogue) (see BR [2] 791-93). He therefore may not have been aware of Henry Banes’ legacy to Catherine and is certainly unlikely to have recorded details of it in his account books or his journal. Any papers of Frederick Tatham’s relating to the period of Catherine Blake’s residence with him, which may have referred to Banes’ legacy, have not been traced. It seems highly probable then that Catherine did receive her brother-in-law’s bequest.

In The Stranger from Paradise, Bentley asserts that Catherine remained at Frederick Tatham’s residence and did not move to her own lodgings until “early 1831.”59↤ 59. Bentley, Stranger 444. However, a transcription of a letter from Tatham to an unnamed correspondent, and two letters from Catherine herself to Sir George O’Brien Wyndham, third Earl of Egremont, suggest that Catherine had moved to lodgings two years earlier.60↤ 60. See BR (2) 495-96, 498. Tatham’s letter is transcribed by Thomas Hartley Cromek, son of Blake’s former employer Robert Cromek, in his ms. “Recollections of Conversations with Mr John Pye” (1865) 56-58 (see BR [2] 871n37). Dennis Read has identified Tatham’s correspondent as an acquaintance of William and Catherine Blake, the engraver John Pye (see Dennis Read, “‘An eminent but neglected genius’: An Early Frederick Tatham Letter about William Blake,” English Language Notes 19 [September 1981]: 30). If Pye was Tatham’s correspondent, it is difficult to reconcile Pye’s sending a letter for Catherine to Fountain Court in early 1829 when he had called on her at Cirencester Place a year earlier (see BR [2] 482). Is it possible that Catherine returned to live at Fountain Court for a brief period between the spring of 1828 and the spring of 1829? Conversely, Pye, aware of Catherine’s leaving Cirencester Place, but unsure of her address in early 1829, and unaware of Banes’ recent death, may have sent his letter to Catherine’s previous residence, 3 Fountain Court, assuming her brother-in-law would ensure she received it. In his letter, dated 11 April 1829, Tatham writes: ↤ 61. BR (2) 495. Tatham, possibly for the sake of brevity, omits any reference to Catherine Blake’s having formerly resided either with John Linnell or himself. However, see note 60.

But to answer your enquiry, which would have been done before, but that in consequence of Mrs Blake’s removal from Fountain Court to No 17. Upper Charlotte St Fitzroy Square, a wrong address was put on the letter at Fountain Court and it was only received by her the day before yesterday.61In the light of this evidence, Bentley has revised his theory as to where Catherine resided after leaving Linnell’s town house. In Blake Records he suggests that: ↤ 62. BR (2) 754-55. However, Bentley also suggests that Catherine moved from the Tathams’ to private lodgings in “early 1830” (BR [2] 755).

Catherine Blake moved in the spring of 1828 from Linnell’s house in Cirencester Place to lodge with a baker at 17 Upper Charlotte Street, south-east of Fitzroy Square.As I hope to demonstrate in a paper currently in preparation, several details in this passage require further revision. However, Henry Banes’ will does appear to confirm Bentley’s suggestion that Catherine Blake moved from Tatham’s residence to her own lodgings before 11 April 1829. Catherine Blake was almost certainly living at Frederick Tatham’s residence in late January-early February 1829, when she learned of the death of her brother-in-law Henry Banes. As Louisa Best was granted probate as executrix just over three weeks after Banes’ death, Catherine could have received her portion of the estate as early as late February or early March 1829. Although it is likely that Catherine knew of Banes’ bequest to her before his death, I contend that either news of, or her acceptance of, her legacy begin page 89 | ↑ back to top in the spring of 1829 influenced Catherine’s decision to move from Tatham’s residence to her own lodgings. Bentley suggests that Catherine was “kept . . . out of want for the rest of her life” in July 1829 when Lord Egremont generously paid her £84 for her late husband’s watercolor The Characters in Spenser’s “Faerie Queene.”63↤ 63. BR (2) 499. However, if approximately three months earlier Catherine had received her legacy of £20 together with “Bedsteads Beds & pillows Bolsters & sheets & pillow cases Tables Chairs & crockery,” then Banes’ bequest, rather than Egremont’s purchase, initially may have put Catherine out of need by facilitating her move to her own lodgings.

Shortly thereafter she moved in with the Tathams in Lisson Grove to look after them. . . . According to Tatham, “She then returned to the lodging in which she had lived previously”. She had returned to Upper Charlotte Street by the spring of 1829, for on 11 April Frederick Tatham wrote “of Mrs Blake’s removal . . . to No 17. Upper Charlotte St”62

In his “Life of Blake,” Tatham wrote: ↤ 64. Frederick Tatham, “Life of Blake” ms. (cited BR [2] 690).

[Catherine Blake] resided for some time with the Author of this whose domestic arrangements were entirely undertaken by her; until such changes took place that rendered it impossible for her strength to continue in this voluntary office of sincere affection & regard.64It is unclear what Tatham is referring to when he writes of “such changes.” Bentley appears to interpret this passage as meaning that Catherine’s move to her own lodgings was due to infirmity.65↤ 65. See BR (2) 755; Bentley, Stranger 444. However, both the new evidence of Henry Banes’ legacy to Catherine and the likelihood of her removal from Tatham’s residence at a considerably earlier date than has previously been recognized suggest that other factors may have influenced Catherine’s decision to move out of Tatham’s chambers.66↤ 66. Perhaps, as had been the case a year earlier when Catherine left Linnell’s residence, the decision to move was not entirely of her own making. Despite Tatham’s close friendship with Catherine between 1827 and 1831, the relationship appears to have shown signs of occasional strain. Joseph Hogarth records a heated disagreement between Catherine and Tatham which appears to have occurred at some point after Catherine’s departure from Tatham’s residence during spring 1829 (see BR [2] 493-94). However, this does not appear to have been a factor in Catherine’s move. I suspect that by “such changes” (BR [2] 690) Tatham may be referring to the domestic changes which are likely to have accompanied his marriage, which must have taken place some time before Catherine’s death in the autumn of 1831. Gilchrist, who interviewed and corresponded with Tatham, states that Catherine Blake “died in Mrs Tatham’s arms” (Gilchrist 357). Indeed, Banes’ legacy coupled with Lord Egremont’s purchase may have been the reason for Catherine’s withdrawal of her application to the Artists’ General Benevolent Institution around January 1830 and for her return of Princess Sophia’s gift of £100, its being something “she could dispense with.”67↤ 67. BR (2) 502; A. C. Swinburne, William Blake (1868), cited BR (2) 462-63.

A New Reference to William Blake

Following the passage in his will outlining his legacy to Catherine Blake, Henry Banes inserted: “I also beg Mr Blakes acceptance of my wearing apparel.” In the early nineteenth century, the bequest of clothes in wills was a common practice. As Jane Cox has observed, “Clothes were much more expensive and prized. . . . Coats . . . and even shirts and underwear might be left to relatives and friends.”68↤ 68. Cox 28. Nevertheless, when writing his will in December 1826, it must have been particularly evident to Henry Banes that both Blake as the wearer and Catherine as the likely repairer of her husband’s coats, trousers, shirts, and other costly “wearing apparel” could make effective use of such a bequest.69↤ 69. Similarly, Sarah Banes’ garments may have been given to Catherine after Sarah’s death in March 1824.

A year earlier, on his first visit to the Blakes’ two rooms in Fountain Court, Henry Crabb Robinson recorded of William Blake that: “Nothing could exceed the squalid air both of the apartment & his dress.”70↤ 70. H. C. Robinson, Diary 17 December 1825, cited BR (2) 426. In the revised diary entry written a quarter of a century later for his “Reminiscences” (1852), Robinson states that Blake’s “linen was clean” (cited BR [2] 698). Robinson also intimates that both Blake and his wife’s dress were of an “offensive character,” despite the couple’s “air of natural gentility.”71↤ 71. Robinson, Diary 17 December 1825, cited BR (2) 426. This statement seems reminiscent of George Cumberland’s note on visiting Blake at 17 South Molton Street on 3 June 1813: “Called Blake—still poor still Dirty” (cited BR [2] 316). On 21 April 1815, George Cumberland, Jr., reported to his father “found [Blake] & his wife drinking Tea, durtyer than ever . . .” (cited BR [2] 320). Around 1832, Tatham posed the question “Had poor half starved Blake ever a suit of clothes beyond the tatters on his Back?”72↤ 72. Cited BR (2) 676-77. However, Gilchrist, perhaps citing the recollections of Linnell, George Richmond or Samuel Palmer, observed that: ↤ 73. Gilchrist 313. This description may partially derive from a passage in a letter from Samuel Palmer to Gilchrist, cited in Gilchrist’s Life, which describes a visit Palmer and Blake made to the Royal Academy c. 1825. “Blake in his plain black suit and rather broad-brimmed, but not quakerish hat . . .” (Gilchrist 283). In a letter to Dante Gabriel Rossetti, dated 6 December 1860, Thomas Woolner records an anecdote a woman who met Blake as a child had told him. In that anecdote, which Bentley suggests occurred in late 1821, Blake is described as “a poor old man, dressed in such shabby clothes . . .” (cited BR [2] 382). However, this had not always been the case. According to Frederick Tatham, 30 years earlier the Blakes had owned “clothes to the [valued] amount of [£]40 . . .” (BR [2] 676).

In [Blake’s] dress there was similar triumph of the man over his poverty to that which struck one in his rooms. Indoors he was careful, for economy’s sake, but not slovenly: his clothes were threadbare, and his grey trousers had worn black and shiny in front, like a mechanic’s. Out of doors he was more particular, so that his dress did not, in the streets of London, challenge attention either way. He wore black knee breeches and buckles black worsted stockings, shoes which tied, and a broad-brimmed hat. It was something like an old-fashioned tradesman’s dress. But the general impression he made on you was that of a gentleman, in a way of his own.73begin page 90 | ↑ back to top Henry Banes, having married in the 1780s, is likely to have been of a similar age, and evidently not of a dissimilar build, to Blake. Although a tradesman, Banes was wealthy enough to pay the rates, appear in the residential section of Holden’s Triennial Directory and leave a provable will. As a consequence, one can imagine that Banes, in bequeathing his wearing apparel to Blake, had intended to leave his brother-in-law a number of presentable garments to replace those Gilchrist described as “the common, dirty dress, poverty, and perhaps age, had rendered habitual.”74↤ 74. Gilchrist 316.

Louisa Best: William and Catherine Blake’s Niece?

Henry Banes left the remainder, and clearly the majority, of his estate to his appointed “sole Executrix” Louisa Best, wife of Richard Best, watch escapement maker.75↤ 75. Richard and Louisa Best had five children: Charles Best, born 1 April 1805, baptized Old Church, St. Pancras (St. Pancras parish church, Euston Road) 1 May 1805; Charlotte Louisa Best, born 16 August 1807, baptized Old Church, St. Pancras 14 August 1808; Elizabeth Best, born 19 December 1809, baptized 18 July 1817, Old Church, St. Pancras; Thomas Best, born 4 December 1813, baptized 18 July 1817, Old Church, St. Pancras; Richard John Best, born 20 March 1815, baptized 18 July 1817, Old Church, St. Pancras (see IGI; London Metropolitan Archives X030/004; X100/34). No reference to the marriage of a Louisa and Richard Best prior to 1805 has been traced. In the PCC copy of Banes’ will, Louisa and her son Thomas Best are recorded as resident at 3 Fountain Court “on the sixth day of ffebruary 1829” (PRO PROB 11/1751), just over a fortnight after the death of Henry Banes. This evidence suggests that the Bests were resident at Banes’ house before his death. In editions of Robson’s London Directory 1833-38, Richard Best is described as a “watch escapement maker” conducting business from 3 Fountain Court, Strand (see, for example, Robson’s London Directory [London: William Robson, 1835] 348). It is curious that Richard Best is not listed as watch escapement maker in directories before this date. However, if Banes also left his house to Louisa Best, such a bequest could have enabled Louisa’s husband to launch his own business. In 1839 Louisa Best replaced Richard Best as ratepayer for 3 Fountain Court (COWAC, B272). Richard Best is not listed in the 1841 census entry for the property. Therefore it seems likely that he died around 1839. However, the firm of “Richard Best, Watchmaker,” appears to have remained at 3 Fountain Court, along with Louisa Best and several of her children, until 1844 (see Post Office London Directory [London: Kelly & Co, 1844] 233). By 1845 William Walker replaced Louisa Best as ratepayer (see COWAC, B306). Banes left Louisa:

the remaining part of my household goods as aforesaid with the clock & my watch & silver plate (& pictures what is worth her acceptance) and all the remainder of my property in money & outstanding debts of whatever nature or description for her whole and sole use or disposal.The precise identity of Louisa Best, Henry Banes’ “sole Executrix,” is unclear. An examination of Banes’ will provides little explicit evidence that at the time of writing his will in December 1826 he expected to be survived by any children. It is possible that Louisa Best was Henry Banes’ niece. Conversely, she may have been an acquaintance or lodger whom Banes had grown fond of and wished to acknowledge in his will. But, as we have seen, Banes did not merely leave Louisa Best a bequest; he made her, rather than his sister-in-law Catherine Blake, sole executrix. A possible explanation for Banes’ choice of Louisa as executrix could be that he deemed the position and its responsibilities too onerous for Catherine (who would have been 64 in late 1826). However, this does not satisfactorily explain why Louisa inherited the majority of Banes’ estate.

A more straightforward explanation may lie in the possibility that Louisa Best was a more intimate relation of Henry Banes than Catherine Blake. I suggest that whereas Catherine was Banes’ sister-in-law, Louisa could have been his daughter.76↤ 76. John Linnell describes 3 Fountain Court as “a private House Kept by Mr Banes” (BR [2] 526-27). As suggested above, Banes’ legacy to Louisa Best may therefore have included the leasehold to 3 Fountain Court. This is suggested by the fact that Louisa remained resident at this address after Banes’ death and after the death of her husband c. 1839. In the 1841 census entry for 3 Fountain Court, Louisa Best describes herself as “ind[ependent]” (PRO HO 107/731/3 15). If Banes was the owner or leaseholder of 3 Fountain Court, the property, as real estate, would have passed automatically to the next of kin without explicit reference in Banes’ will. At my request, Philippa Hoskin of the Borthwick Institute of Historical Research, University of York, the respository of the records of the Prerogative Court of York, examined a transcript of Henry Banes’ will. Hoskin observed that the absence of the word “daughter” in the will in no way precludes the possibility that Louisa Best was the daughter of Henry Banes.77↤ 77. Banes’ will is comparatively brief and makes no provision for the eventuality of a legatee’s predeceasing him, as occurred with William Blake. She added that the context of the will suggests that its writer was a widower leaving the majority of his estate to his daughter. Although Louisa Best is not explicitly named as the daughter of Henry Banes, neither are the other legatees (William and Catherine Blake) named as Banes’ brother- and sister-in-law.78↤ 78. In reply to my query, Stephen Freeth, Keeper of Manuscripts at the Guildhall Library, London, wrote: “I have searched the baptism register of the parish of St Bride, Fleet Street (Guildhall Library Ms. 6541/1) but unfortunately no entry for Louisa or Louiza Banes was found. The years 1789 to 1792 were searched. I also checked the International Genealogical Index (both the microfiche version and the web site) but no reference to Louisa Banes of the parish of St Brides, Fleet Street was found” (email, 2 October 2003). The International Genealogical Index contains no other baptismal record for a Louisa (or Louiza) Banes, daughter of Henry and Sarah Banes. However, nor does the IGI include a record of the marriage of a Richard and Louisa Best. If Henry and Sarah Banes and Richard and Louisa Best were living in London, records of the baptism of Louisa Banes and the marriage of Richard and Louisa Best may survive in the registers of the 10-20% of London parishes not currently covered by the IGI. See Keri Davies, “William Blake’s Mother: A New Identification,” Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly 33.2 (fall 1999): 38n14. Indeed, the fact that in her testimony at the proving of Banes’ will Louisa was not obliged to testify to the intimacy or longevity of her relationship with Henry Banes, as her son Thomas and her lodger John Barrow were, again suggests that Louisa was Banes’ daughter. In addition, begin page 91 | ↑ back to top in his will Banes makes no bequest to Louisa’s husband Richard Best. Instead he stipulates that his legacy to Louisa is “for her whole and sole use or disposal.” Banes does not use this phrase in his bequest to Catherine Blake. It seems likely that by including this phrase, Banes intended to ensure that his only daughter maintained control over her legacy despite her marriage to Richard Best. Banes’ choice of Louisa as “sole Executrix” would have ensured that, as a married woman, her entitlement to and share of the estate was protected. It is also interesting to note that in the record of the proving of the will cited above, Louisa is the authority for the fairly precise (to the month) dating of the death of Sarah Banes almost five years earlier. This might be deemed a detail that a daughter of Henry and Sarah Banes could be relied upon to remember.

According to the marriage register for St. Bride’s Church, Fleet Street, Henry and Sarah Banes were married on 16 December 1788. The 1841 census return for 3 Fountain Court, Strand, records that Louisa Best was 50 years old in the summer of that year.79↤ 79. PRO HO 107/731/3 14-17 [6 June 1841]. It is therefore likely that she was born between 1790 and 1791. That Louisa Best was born a year or two after the marriage of Henry and Sarah Banes also supports the theory that Louisa was Henry and Sarah’s daughter. Sarah Banes’ relatively mature age at the time of her marriage (approximately 31) in 1788 suggests that Louisa may have been Henry and Sarah Banes’ only surviving child.80↤ 80. See Boucher-Butcher family tree, Bentley, Stranger xx. In Blake Records, Bentley observes that: “Blake and his wife had twenty brothers and sisters, but none of them is known to have had children . . . .”81↤ 81. BR (2) xxxvi. If Louisa Best is the daughter of Henry Banes, then she is the only niece of William and Catherine Blake traced to date.82↤ 82. None of Blake’s surviving writings contains a reference to a “Louisa” or “Louisa Best.” However, in the table of contents of the volume of William Wordsworth’s Poems (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, & Brown, 1815), which Henry Crabb Robinson loaned to Blake in late 1825, “I Met Louisa” [“To Louisa”] is one of the 32 titles marked “X” (E 665). But, as David Erdman observes, Robinson “may have put the X’s in the list of contents before he lent it to Blake” (E 887). If Louisa Best’s age was recorded slightly inaccurately in the 1841 census return for 3 Fountain Court, as that of her son Thomas Best appears to have been, then she may have been born as early as the summer of 1789. IGI records give the date of Thomas Best’s birth as 4 December 1813. However, the 1841 census return for 3 Fountain Court records Best’s age as 25 on 6 June 1841, suggesting that he was born in 1815 or 1816. Could the infant Louisa Best, possibly the daughter of Catherine’s sister, Sarah, and the only traced offspring of William and Catherine Blake’s siblings, have been born at the time of the composition, relief etching, printing and coloring of Blake’s Songs of Innocence (1789)? See images of mothers and babies on both plates of The Ecchoing Green, A Cradle Song, Spring, Infant Joy; also the texts of the three latter poems. See also Infant Sorrow and the image of mother and child on the plate of The Fly in Songs of Experience.

We cannot be sure when Louisa Best and her family moved to 3 Fountain Court, Strand. However, it seems significant that during the proving of Banes’ will on 6 February 1829, barely a fortnight after Henry Banes’ death, Louisa, her son Thomas and her husband were described as resident at this address. This detail, coupled with Louisa and her son Thomas’ testimony that they searched for and found Banes’ will on the evening of the day of his death (20 January 1829), suggests that the Best family may have been living at 3 Fountain Court before Banes’ death. If Henry Banes had been ill for a period of time before his death, Louisa, in all likelihood Banes’ only daughter, may have moved to Banes’ house along with her husband and children in order to care for her father.

If, as has been suggested above, Louisa Best was William and Catherine Blake’s niece, her sons Thomas and Richard were two of the Blakes’ grandnephews. In his testimony recorded in the probate copy of Henry Banes’ will, Louisa Best’s 15-year-old son Thomas describes himself as a “print colorer.”83↤ 83. PRO PROB 11/1751. Twelve years later, in the 1841 census return for 3 Fountain Court, Thomas and Richard both gave their occupation as “artist.”84↤ 84. PRO HO 107/731/3 15. I have traced no record of Richard Best Jr. as a print colorer. However, it seems likely that as Thomas and Richard both described themselves as artists in 1841, they were both (apprentice?) print colorers c. 1829. They may have been employed as print colorers at Rudolph Ackermann’s Repository nearby at 96 Strand. However, another source of training and employment is discussed below. Between 1834 and 1839 a Thomas Best, painter of domestic scenes, residing at Beaufort Buildings, exhibited one painting at the Royal Academy and three at the Society of British Artists (Graves, Dictionary of Artists 24). The eastern side of Beaufort Buildings backed onto the western side of Fountain Court, Strand, which included the residence of the Best family. The street was often used in trade and other directories to distinguish Fountain Court, Strand, from the three other Fountain Courts in early nineteenth-century London. Best’s sole exhibit at the Royal Academy, “Miss Cust” (exhibited 1834), may have been a portrait of Charlotte, Mary or Emily, daughters of Christopher Cust, the Bests’ (and formerly the Blakes’ and the Banes’) neighbor at 7 Fountain Court, Strand (see Graves, Royal Academy 1:187; IGI; St. Clement Danes [Savoy Ward] rate books for 1822-29, e.g., COWAC, B126-27). Another painting by Thomas Best, “Trentham,” a Bay Race Horse Galloping up on Newmarket Heath, was auctioned at Christie’s, London, on 21 November 1986 (information kindly supplied by the Witt Library, Somerset House). Their parents Richard and Louisa Best were the recorded rate-payers for 3 Fountain Court between 1829 and 1845. The fact that Louisa Best was appointed sole executrix in Henry Banes’ will in December 1826 suggests that Louisa and her family, if not immediate relatives, were almost certainly fellow lodgers or regular visitors of Henry Banes at Fountain Court during the early-mid-1820s. William Blake, John Barrow and the artists who visited them at 3 Fountain Court between 1821 and 1838 may have inspired Thomas and Richard Best to become first print colorers and later artists.85↤ 85. Gilchrist observes that after Blake’s death, “Aided by Mr. Tatham [Catherine Blake] also filled in, within Blake’s lines, the colour of the engraved books” (Gilchrist 357). See also references to Catherine’s coloring of copies of Blake’s works in J. T. Smith, Nollekens and His Times (1828) (cited BR [2] 609) and Frederick Tatham, ms. “Life of Blake” (c. 1832) (cited BR [2] 690). Could the Best brothers also have assisted Catherine and have been third and fourth hands in the coloring and finishing of any copies of Blake’s illuminated books still in Catherine’s possession c. 1827-31? Thomas and Richard, begin page 92 | ↑ back to top who in August 1827 were aged 13 and 12 respectively, whether they were the grandsons of Henry Banes or merely the sons of Banes’ acquaintance Louisa Best, could very well have visited the Blakes’ two rooms on the first floor of 3 Fountain Court. On the panelled walls of the Blakes’ front room, which served as both reception room and printing studio, the Best brothers would have seen a “good number” of temperas and watercolors.86↤ 86. See George Richmond’s description of the interior of 3 Fountain Court, cited BR (2) 753. They may also have observed William and Catherine Blake as they drew and painted or while they printed, colored and finished copies of the illuminated books.

John Barrow, Publisher of “Mrs Q”

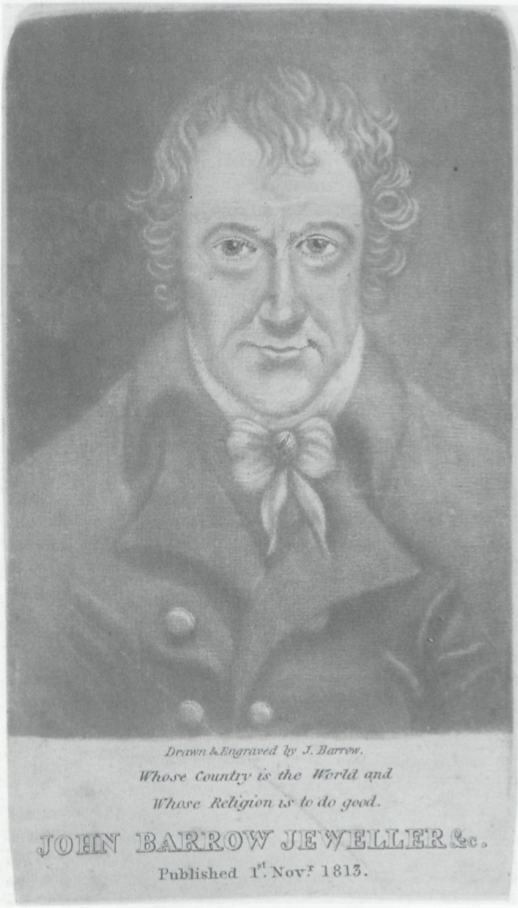

Henry Banes’ will also provides new information concerning the identity of the publisher of one of Blake’s last commercial engravings. John Barrow’s signature as witness of Henry Banes’ will in December 1826, and his testimony at the proving of Banes’ will in February 1829, reveal that the wine cooper and the artist, and later lodger at 3 Fountain Court, had been “well acquainted . . . for several years.”87↤ 87. PRO PROB 11/1751. J. Barrow exhibited 21 works at the Royal Academy between 1797 and 1836 (see Graves, Royal Academy 1:129-30). According to Graves, Barrow also exhibited four enamels at the [Royal] Society of British Artists’ gallery in Sussex Street (Graves, Dictionary of Artists 16). However, Jane Johnson lists eight works exhibited by Barrow at Sussex Street between 1824 and 1837 (Johnson 27). I wish to thank Catherine Taylor at Cambridge University Library for this information. The Society of British Artists was formed in 1824 and Barrow appears to have been a founding member. Blake as well as Barrow would have been acquainted with two of the society’s first presidents, Thomas Heaphy and James Holmes (see E 773; BR [2] 345). The Royal Academy exhibition catalogues for 1831, 1835 and 1836 and the Society of British Artists’ exhibition catalogues for 1832 and 1836 record Barrow as resident at Fountain Court (Graves, Royal Academy 1:130, Johnson 27). David Worrall has observed that “Remarkably, Barrow’s final residence—between 1831 and 1836—was Fountain Court, Strand, Blake’s last address” (see Worrall 180n1). Even more remarkably, in Robson’s Directory of 1832 (London: William Robson, 1832) n. pag., John Barrow is recorded as an “artist” resident at 3 Fountain Court, Strand. Barrow’s address in the Royal Academy exhibition catalogue for 1829 is recorded as 26 Denton Street, St. Pancras (Graves, Royal Academy 1:130). St. Pancras is the parish in which Louisa Best and her family appear to have been resident before moving to Fountain Court (see note 75). However, at the proving of Banes’ will at Doctor’s Commons on 13 February 1829, Barrow testified that he was resident at “ffountain Court Strand” (PRO PROB 11/1751). As stated above, Barrow was sole recorded witness at the writing of Henry Banes’ will. If, as Jane Cox suggests, “wills were witnessed by whoever happened to be in the house” (Cox 24), Banes’ choice of John Barrow as witness may suggest that Barrow was a lodger at 3 Fountain Court as early as December 1826. In that case it is possible that he may have moved to 3 Fountain Court soon after Sarah Banes’ death in March 1824. However, Banes’ house may not have provided adequate space for two separate artists’ studios. Evidence suggests that Banes had another lodger on the second floor of 3 Fountain Court (see BR [2] 439). However, as I will demonstrate in a forthcoming paper, this was unlikely to have been John Barrow. Therefore, it seems likely that Barrow occupied the first floor of 3 Fountain Court only after Catherine’s removal in mid-September 1827 (see BR [2] 471). Even if Barrow was not resident at Henry Banes’ house in December 1826 when witnessing Banes’ will, the fact that he was sole witness to Banes’ will clearly suggests a friendship between the two men. This relationship between Banes and Barrow, miniature painter, Royal Academy exhibitor and member of the Society of British Artists, suggests that Banes may have taken an active interest in both Barrow and Blake’s works. It may be significant that in his will, Henry Banes bequeathed Louisa Best “pictures” (PRO PROB 11/1751). It is now clear that in early-mid-1820, over six years before witnessing Henry Banes’ will, John Barrow had employed Banes’ brother-in-law William Blake to engrave the late François Marie Huet Villiers’ portrait of George IV’s former mistress, Mrs. Harriet Quentin (illus. 8).

According to the engraving’s imprint, the publisher of Blake’s engraving, entitled “Mrs Q,” was “I. Barrow.” In The Separate Plates of William Blake (1983), Robert Essick suggests that I. Barrow “was either the J. Barrow who exhibited enamels and miniature portraits in London from 1797 to 1836, or John Barrow, who exhibited portraits at the Society of Artists from 1812 to 1816.”88↤ 88. Essick, Separate Plates 199. There appears to be little evidence for G. E. Bentley, Jr.’s claim that the publisher of “Mrs Q” was the “notoriously radical print-seller” Isaac Barrow (Bentley, Stranger 356). As David Worrall has observed, Essick’s first identification is confirmed by the fact that between 1820 and 1825 J. Barrow, portrait painter, and J. Barrow, publisher, resided at the same address.89↤ 89. Worrall 180n1. The publisher’s address featured in the imprint of the second state of “Mrs Q” and its companion print “Windsor Castle” (1821) is “Weston Place, St. Pancras.” According to the catalogue for the Royal Academy exhibition of 1822, J. Barrow, miniature painter, is recorded as residing at 1 Weston Place, St. Pancras.90↤ 90. Graves, Royal Academy 1:130. Another “John Barrow, painter” is recorded as resident at Weston Place, St. Pancras, in Royal Academy exhibition catalogues from 1812 to 1816 and 1823 (Graves, Royal Academy 1:130). In 1815 John Barrow exhibited a painting of “Mr J. Barrow, Senr.” at the Royal Academy exhibition for that year (Graves, Royal Academy 1:130). Therefore, it seems likely that “John Barrow” was the son or nephew (and quite possibly the apprentice) of “J[ohn], Barrow.” It is of course possible that “John Barrow” was the publisher of “Mrs Q.” However, the established link between John Barrow Sr. and Blake through Henry Banes, the use of the initial “I.” for “J.” in the two prints and “J.” in the Royal Academy exhibition catalogue entries, and Banes, Barrow and Blake’s similarity in age, suggest that John Barrow Sr. employed Blake. Nine years later, in the Royal Academy exhibition catalogue of 1831, “J. Barrow” is recorded as resident at “[3] Fountain Court, Strand.”91↤ 91. Graves, Royal Academy 1:130. Just over two years after witnessing Henry Banes’ will, when providing testimony at the proving of the will, Barrow was recorded (alongside Richard Best, Louisa Best and their son Thomas) as a fellow resident at 3 Fountain Court. According to his burial record, Barrow, who resided at 3 Fountain Court until his death, was 81 years old when he was buried in St. Clement Danes’ churchyard on 25 March 1838 (see COWAC, SCD 19, burial no. 1069). Therefore, having been born around 1757, Barrow was an exact contemporary of Blake. As observed earlier, at the proving of Banes’ will Barrow testified that he had been “well acquainted with . . . Henry Banes . . . for several years before and down to the time of his death.”92↤ 92. PRO PROB 11/1751. It begin page 93 | ↑ back to top

It is intriguing to think of John Barrow, a miniature painter, first employing Blake to engrave a commercial fancy print and then publishing it. However, evidence suggests that Barrow was not just a miniaturist. In May 1828 the 28-year-old Theodore Lane, widely regarded as a painter and engraver of great promise, died when in a freak accident he fell through a skylight at the horse repository in Gray’s Inn Road. Three years after Lane’s death his associate, the sporting journalist and author Pierce Egan, recalled that at the age of 14, Lane: ↤ 94. Battle Bridge is the former name of King’s Cross, an area which borders the parish of St. Pancras. 17 Spann’s Buildings, St. Pancras, is recorded as the address of J. Barrow, miniature painter, in the Royal Academy exhibition catalogues between 1808 and 1815 (Graves, Royal Academy 1:129-30). ↤ 95. Pierce Egan, “Biographical Sketch of the Life of the Late Mr Theodore Lane,” The Show Folks (London: M. Arnold, 1831) 34. Egan had provided the letterpress to accompany Lane’s 36 etchings entitled The Life of an Actor (1825) and Lane illustrated with etchings and woodcuts Egan’s Anecdotes of the Turf, the Chase, the Ring and the Stage (1827). Lane appears to have been a neighbor of Barrow’s at Spann’s Buildings (see Egan, Show Folks 35). As observed above, Barrow appears to have lived at 17 Spann’s Buildings from 1808 until sometime between 1815 and 1820 (see Graves, Royal Academy 1:129-30). Lane is recorded as resident at this address in 1816 (see Graves, Royal Academy 2:381). Lane also painted a portrait of “Mr Barrow” exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1826 (see Graves, Royal Academy 2:381). Another apprentice of Barrow appears to have been the miniaturist E. Preston, who between 1824 and 1843 exhibited 24 portraits at the Royal Academy, Society of British Artists and the New Watercolour Society. Preston also exhibited his portrait of “Mr Barrow” at the Royal Academy exhibition in 1826, the year Lane exhibited his portrait of the same subject (see Graves, Royal Academy 3:202).

was apprenticed to a Mr Barrow at Battle Bridge94 a colourer of expensive prints, and who was considered a man of ability in that line. It was during his apprenticeship that Lane first displayed a taste for drawing. . . . His juvenile sketches on first being shown to Mr Barrow, he (Mr B.) was very much pleased with them, and in the kindest manner pointed out to Theodore those defects which first arise from youth and inexperience. LANE gratefully profited by his instructions.It is significant that Egan describes John Barrow as “a colourer of expensive prints,” the profession to which Barrow’s later fellow residents at 3 Fountain Court, Strand, Thomas and Richard Best were apprenticed. John Barrow, print colorer and miniature painter, may have been the J. Barrow who in 1782 traded as printseller, publisher, and very possibly the engraver of satirical prints at 11 St. Bride’s Passage, Fleet Street.96↤ 96. See George 5:846n3 and cat. nos. 6010 and 6014. For other prints published by J. Barrow, see George, cat. 5, 5985, 5986, 6004, 6023, 6029, 6167, 6168, 6175, 6208, 6229, 6251, 6261. This address faced St. Bride’s Church, where Henry and Sarah Banes would marry six years later. By November 1782, J. Barrow had moved a few blocks west to Dorset Street, Salisbury Court, Fleet Street. It was from this address that he published a satirical engraving, possibly his own, The American Rattlesnake Presenting Monsieur His Ally a Dish of Frogs.97↤ 97. George, cat. 5, 6039. Detlef Dörrbecker refers to this print as an example of serpent symbolism utilized in the early 1780s by “various British caricaturists to deride the rebellious and ‘serpent form’d’ colonists” in America. As Dörrbecker suggests, such a print may have been one of the sources for Blake’s design for the title page of EUROPE a PROPHECY (1794).98↤ 98. See Detlef Dörrbecker, ed., William Blake: The Continental Prophecies, Blake’s Illuminated Books, vol. 4 (London: Tate Gallery Publications/William Blake Trust, 1995) 171. The engraving is reproduced in the same volume (251, supplementary illustration 3). John Barrow may also have been the “J. Barrow” who designed, engraved and published a mezzotint portrait on what appears to be a business flier or trade card for “John Barrow, Jeweller” in 1813, suggesting markedly different political sympathies (illus. 9). The imprint continues: “Drawn & Engraved by J. Barrow. / Whose Country is the World and / Whose Religion is to do good. / John Barrow Jeweller &c. / Published 1st Novr 1813.”99↤ 99. British Museum Department of Prints and Drawings, cat. no. 1872-11-9-423. I have been unable to trace a John Barrow, jeweller, trading in London in 1813. However, entries for a Henry Barrow, wholesale jeweller of 12 Thavies Inn, Holborn, appear in Underhill’s Biennial Directory for the Years 1816 and 1817 (London: Underhill, 1816) n. pag., and Kent’s Directory, 1817 25. According to the Royal Academy exhibition catalogues, John Barrow lived in Leather Lane, Holborn, between 1797 and 1801 (see Graves, Royal Academy 1:129). There is also a will for a John Barrow, jeweller, of Tottenham Court Road, PRO PROB 11/989 (proved 26 July 1773). The second and third lines of the imprint are a slight misquotation from “WAYS AND MEANS of Improving the Condition of Europe, Interspersed with Miscellaneous Observations,” chapter 5 of part two of Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man, published in 1792. “Independence is my happiness, and I view things as they are without regard to place or person; my country is the world, and my religion is to do good.”100↤ 100. Thomas Paine, Rights of Man (Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin, 1969) 228. For the significance of the second part of Paine’s Rights of Man for Blake two decades earlier, see Michael Phillips, William Blake: The Creation of the Songs From Manuscript to Illuminated Printing (London: British Library, 2000) 47. This quotation and the fact that the engraving bears some resemblance to Paine suggest that the second and third lines of the imprint may apply to Paine and not to “J[ohn]. Barrow.” Compare Thomas Sharp’s engraving of Paine, after George Romney (1793) (National Portrait Gallergy, D15322). See also James Godby’s engraving of Paine, after an unknown artist (1805) (NPG, D5445). No publisher’s address is begin page 95 | ↑ back to top

Mr Barrow saw, or thought he saw, in those early sketches that sort of talent indicative of future greatness; and he therefore encouraged him to proceed with the most unremitting industry until he overcame all the difficulties which every artist has to surmount on his first entrance into life. Mr Barrow always entertained an opinion that one day or another the proud initials of R.A. might be added to his name.95