article

Jonathan Spilsbury and the Lost Moravian History of William Blake’s Family

The engraver, painter, and miniaturist Jonathan Spilsbury (1737-1812), who had strong links to the Moravian church, was most likely, as I shall demonstrate, an associate of William Blake.*↤ *My research into the Moravian connections of William Blake’s family was funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council. I am most grateful to Lorraine Parsons, archivist, for permission to examine and publish documents in the Moravian Church Library and Archive, Muswell Hill, London. Colin Davies, Will Easton, Keith Schuchard, Angus Whitehead, David Worrall, and Charlotte Yeldham contributed helpfully to my thinking about Blake and Spilsbury. This casts a new light on Blake’s possible involvement in the London Moravian community, with which he had connections through his mother’s early adherence to that faith. The following discussion will take in the circumstances of Spilsbury’s links to the African Chapel in Peter Street, Soho, resemblances to Moravian custom and culture in the reportage of Blake’s death, and the parallels between Blake’s and Spilsbury’s lives in forging a living in the engraving trade.

Bentley’s Blake Records contains three references to a person or persons surnamed “Spilsbury.” On 28 June 1802, Charlotte Collins wrote to William Hayley at Felpham in Sussex about “a new Family settled at Midhurst by the name of Spilsbury—the Gentleman has devoted his Time to the study of animals, and he has lately made a drawing of Mrs Poyntz’s Prize Bull.”1↤ 1. G. E. Bentley, Jr., Blake Records, 2nd ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press) 134, hereafter abbreviated “BR(2)”. The following year, on 21 March 1803, John Flaxman wrote to Hayley: “I am sorry for Mr Spilsbury’s illness.”2↤ 2. BR(2) 150. And on 14 October 1806, Hayley’s young friend E. G. Marsh wrote to him inquiring “I wonder, whether Mr Spilsbury has ever seen Warwick castle, because there is a painting of two lions there, which pleased me . . . beyond anything of the kind I had ever seen.”3↤ 3. BR(2) 231.

Edgar Ashe Spilsbury (1780-1828?) was an animal painter who exhibited at the Royal Academy and the British Institution and, because of the nature of the references, it seems likely that he is the Spilsbury referred to.4↤ 4. See J. C. Wood, A Dictionary of British Animal Painters (Leigh-on-Sea: F. Lewis, 1973) 61. He was the son of the noted “chymist” Francis Spilsbury (1736-93) of Soho Square (author of the learned treatise Free Thoughts on Quacks), and the younger half-brother to Francis Brockhill begin page 101 | ↑ back to top Spilsbury (b. 1761), naval surgeon and amateur landscape painter.5↤ 5. Francis Spilsbury was the author of Free Thoughts on Quacks and Their Medicines: Occasioned by the Death of Dr. Goldsmith and Mr. Scawen; or, A Candid and Ingenuous Inquiry into the Merits and Dangers Imputed to Advertised Remedies (London: Printed for J. Wilkie, No. 171, St. Paul’s Church-yard, and Mr. Davenhill, No. 30, Cornhill, 1776). A “second edition, revised and corrected” appeared in 1777. See Peter Isaac, “Charles Elliot and Spilsbury’s Antiscorbutic Drops,” Pharmaceutical Historian 27.4 (December 1997): 46-48. Francis Brockhill Spilsbury was the author of Account of a Voyage to the Western Coast of Africa: Performed by His Majesty’s Sloop Favourite, in the Year 1805: Being a Journal of the Events Which Happened to That Vessel, from the Time of Her Leaving England till Her Capture by the French, and the Return of the Author in a Cartel (London: Printed for Richard Phillips by J. G. Barnard, 1807); Advice to Those Who Are Afflicted with the Venereal Disease (London, 1789); The Art of Etching and Aqua Tinting, Strictly Laid Down by the Most Approved Masters: Sufficiently Enabling Amateurs in Drawing to Transmit Their Works to Posterity; or, as Amusements among Their Circle of Friends (London: Printed for J. Barker, 1794); Every Lady and Gentleman Their Own Dentist, As Far As the Operations Will Allow, Containing the Natural History of the Adult Teeth and Their Diseases with the Most Approved Methods of Prevention and Cure, etc. (London: Barker, 1791); and Picturesque Scenery in the Holy Land and Syria: Delineated during the Campaigns of 1799 and 1800 (London: Edward Orme, 1803). Edgar Ashe Spilsbury was a friend and sometime protégé of William Hayley.6↤ 6. Ruth Young, Father and Daughter: Jonathan and Maria Spilsbury (London: Epworth Press, 1952) 5.

Bentley notes, however, that the Midhurst Spilsbury “does not seem to be the professional artist to whom Blake refers familiarly in his letter to Hayley of 28 Sept 1804.”7↤ 7. BR(2) 150fn. The relevant passage reads as follows: ↤ 8. Letter 50, “To William Hayley Esqre Felpham,” 28 September 1804. Citations from William Blake’s writings follow the text established by David V. Erdman, ed., The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake, newly rev. ed. (New York: Anchor-Doubleday, 1988), hereafter abbreviated “E”.

I send Washingtons 2d Vol:— 5 Numbers of Fuselis Shakspeare & two Vol’s with a Letter from Mr Spilsbury with whom I accidentally met in the Strand. he says that he relinquishd Painting as a Profession. for which I think he is to be applauded. but I concieve that he may be a much better Painter if he practises secretly & for amusement than he could ever be if employd in the drudgery of fashionable dawbing for a poor pittance of money in return for the sacrifice of Art & Genius. he says he never will leave to Practise the Art because he loves it & This Alone will pay its labour by Success if not of money yet of True Art. which is All—(E 755)8The “Mr Spilsbury” of Blake’s letter is clearly not Edgar Ashe Spilsbury, who had not given up painting, but equally clearly he must be somebody who was well acquainted both with Blake and with Hayley. Our perception of Blake’s life, with Gilchrist (drawing on the testimony of Linnell and Palmer) and Tatham as our primary sources, tends to see Blake as a lonely and isolated figure until taken up in later life by Linnell, Varley, and the “Ancients.”9↤ 9. Prefiguring the familiar fin de siècle trope of the artist’s tragic solitude, on which see, for instance, Frank Kermode, Romantic Image (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1957), especially his chapter 1, “The Artist in Isolation.” This meeting in the Strand with Mr. Spilsbury is evidence, if any were needed, that Blake had a wide social acquaintanceship long before he met Linnell.

Spilsbury cousins included Jonathan Spilsbury (1737-1812), a portraitist and mezzotint engraver. Spilsbury is itself an unusual surname, and there are few artists of that name.10↤ 10. According to Daryl Lloyd, Richard Webber and Paul Longley, Surname Profiler: Surnames as a Quantitative Resource <http://www.spatial-literacy.org/UCLnames>, the surname Spilsbury ranked 5861st among British surnames in 1881, with just 21 occurrences per million names. It occurred most frequently in Worcestershire. (By 1998, it had fallen to 6124th, with 22 occurrences per million names.) The US Census Bureau <http://www.census.gov> records no occurrences of the surname Spilsbury in the 1990 US census. I therefore suggest that Jonathan was the Mr. Spilsbury whom Blake “accidentally met in the Strand,” and that, in view of the recent discovery of the involvement of William Blake’s mother with the Moravian church, it could prove of interest to consider the life and career of Jonathan Spilsbury, another engraver with a Moravian affiliation.11↤ 11. On Blake’s mother and her membership in the Moravian church, see Keri Davies and Marsha Keith Schuchard, “Recovering the Lost Moravian History of William Blake’s Family,” Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly 38.1 (summer 2004): 36-43.

Jonathan Spilsbury came of a Worcestershire family; there were Spilsburys in the West Country in the fifteenth century.12↤ 12. Ruth Young, Mrs. Chapman’s Portrait: A Beauty of Bath of the Eighteenth Century (Bath: George Gregory Bookstore, 1926) 96. He was born at Worcester on 2 February 1737. His mother apprenticed him (9 September 1750) to a cousin, George Spilsbury, a noted “japanner” (manufacturer of lacquer ware) of Birmingham, to whom he was bound for seven years.13↤ 13. Ian Maxted, The London Book Trades, 1775-1800: A Preliminary Checklist of Members (Folkestone: Dawson, 1977) 211. When the seven years were ended, he found his way to London, where he entered Thomas Hudson’s studio soon after the young Joshua Reynolds had quarreled with Hudson.14↤ 14. Young, Father and Daughter 6. Jonathan Spilsbury entered the Royal Academy Schools on 25 March 1776, aged 39. He had exhibited three works at the Society of Artists between 1763 and 1771, and was to show thirteen paintings at the Royal Academy between 1776 and 1784.15↤ 15. Algernon Graves, The Royal Academy of Arts: A Complete Dictionary of Contributors and Their Work from Its Foundation in 1769 to 1904, 8 vols. (London: Henry Graves, 1905-06) 7: 221. Blake exhibited at the Royal Academy on five occasions between 1780 and 1808. Academy students were then admitted for six years, so Spilsbury’s friendship with Blake (admitted 8 October 1779) probably dates from their overlapping time at the R.A. Schools.16↤ 16. Spilsbury’s admission to the R.A. Schools is recorded by Daphne Foskett, A Dictionary of British Miniature Painters, 2 vols. (London: Faber, 1972) 1: 528. Foskett suggests that Spilsbury may have been a pupil of the miniature painter Thomas Worlidge (1700-66). Since Worlidge is associated both with Birmingham and with Bath, as well as London, there is some plausibility in this claim. For Blake at the R.A. Schools, see BR(2) 18-19.

begin page 102 | ↑ back to topAlthough he worked in London, Jonathan did not cut himself off from the West Country. He lived a good deal in Bath and in Bristol, where he painted a portrait of Charles Wesley.17↤ 17. Young, Father and Daughter 9. And it was in Bristol that Spilsbury met Rebecca Chapman (b. 1748), whom he married after a ten years’ courtship.18↤ 18. Young, Mrs. Chapman’s Portrait 95. Rebecca was the eldest daughter of the Rev. Dr. Walter Chapman (1711-91), once Wesley’s colleague in Pembroke College, Oxford, and later prebendary of Bristol Cathedral, a well-known evangelical clergyman in the family home of Bath.19↤ 19. A letter from Walter Chapman to John Wesley dated 27 February 1737/38 is printed in Frank Baker, ed., The Works of John Wesley, Vol. 25: Letters I, 1721-1739 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1980) 531. Walter Chapman’s mother, Mary, seems to have been a friend of Wesley’s brother Samuel.

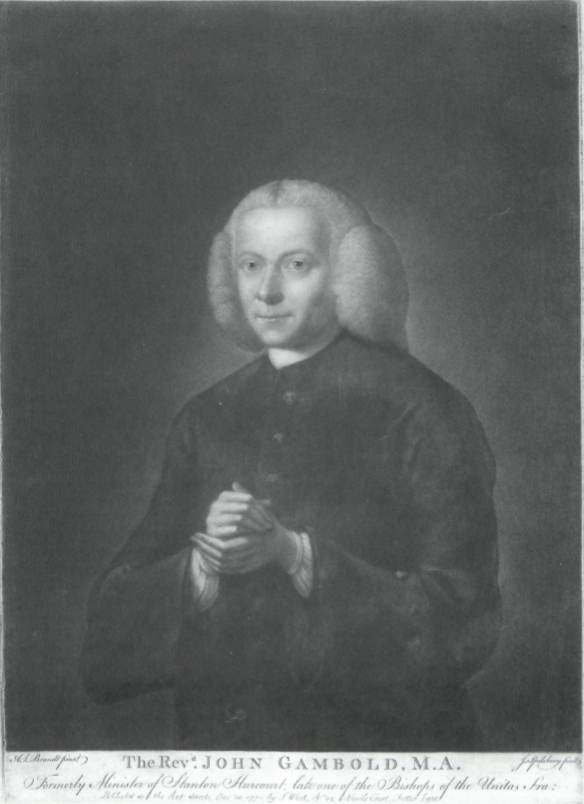

Even before his marriage, Spilsbury had sought membership in the Moravian church, and he was later to engrave portraits of the Moravian “Labourers” (as the church’s fulltime workers were called) John Gambold (illus. 1) and Benjamin La Trobe, the latter after a drawing by Rebecca.20↤ 20. The mezzotint portrait of John Gambold, engraved by Jonathan Spilsbury after Abraham Louis Brandt, was published in 1771; a mezzotint portrait of Benjamin La Trobe, engraved by Jonathan Spilsbury after R. Spilsbury (presumably his wife Rebecca), was published in 1781. In a letter of 116 closely written lines dated 2 October 1769, Spilsbury transcribed for Rebecca “a little discourse delivered at Bedford Oct. 5 N.S. 1751 by the Rt. Rev. late Ordinary of the Brethrens Churches.”21↤ 21. The “Ordinary” was one of the terms by which the Moravians in England referred to their leader, Nicolaus Ludwig, Count Zinzendorf. To this discourse, he added a postscript: ↤ 22. Quoted in Young, Father and Daughter 10. Alexander Gilchrist, in his Life of William Blake, “Pictor Ignotus,” 2 vols. (London: Macmillan, 1863), comments of Catherine Blake: “Uncomplainingly and helpfully, she shared the low and rugged fortunes which over-originality insured as his unvarying lot in life” (1: 38).

I have said nothing upon ye subject of marriage, and you know my reason for being silent on that head. However, I cannot forbear wishing that if ever you change your state, it may be with one who would receive you penniless with as much pleasure as with a million of money, and as to yourself that it may be an act of faith done in ye assurance of God’s grace and favour.22

They married in 1775, and in 1777 Mrs. Spilsbury bore her husband twins. The boy died immediately, but the girl, Rebecca Maria Ann, generally known as Maria, survived.23↤ 23. Young, Father and Daughter 10. The child’s gifts as an artist were early recognized; indeed, the fame of Maria Spilsbury would surpass her father’s.24↤ 24. Graves 7: 221-22 lists 47 paintings exhibited by Miss Mary Spilsbury between 1792 and 1808. There was also a younger son, Jonathan Robert Henry, baptized 7 December 1779 at St. Marylebone.25↤ 25. Data from Charlotte Yeldham, “Spilsbury, (Rebecca) Maria Ann (1777-1820),” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), subsequently cited as Oxford DNB. I presume the child, Jonathan Robert Henry, died in infancy, since he disappears from the documentary record. Susan Sloman, in “Spilsbury, Jonathan (bap. 1737, d. 1812),” Oxford DNB, corrects the inaccurate information provided by some well-regarded reference sources such as Raymond Lister’s Prints and Printmaking: A Dictionary and Handbook of the Art in Nineteenth-Century Britain, which gives Jonathan Spilsbury’s dates as “f. 1766-1823.” I have provided some additional data relating to Spilsbury’s brothers and half-brother.

It seems to have become evident to Spilsbury that he would not find success in the London art world, and 1789 saw him in Ireland, acting as art master to the daughters of Mrs. Tighe, Wesley’s friend, on her estate, Rossana, County Wicklow.26↤ 26. Young, Father and Daughter 13. It was perhaps through the Wesleys or Mrs. Tighe that the Spilsburys became acquainted with Walter Taylor of Portswood Green, Southampton.27↤ 27. Young, Father and Daughter 19. Certainly, by 1798 Jonathan and his daughter were staying at Bevers Hill, Southampton, where they were in daily touch with the Taylor family.28↤ 28. Young, Father and Daughter 20. Walter Taylor of Portswood Green died in 1803, but the friendship formed between his family and the Spilsburys continued, and by 1807, his son, John Taylor, had become engaged to Maria.29↤ 29. Young, Father and Daughter 25. They were married in 1808; Maria was 31 and her husband 23.30↤ 30. Young, Father and Daughter 28.

Maria found some success as a portraitist in Southampton, and Hayley’s friend Richard Vernon Sadleir, a local worthy, sat to her in 1798, responding to the portrait with a set of verses.31↤ 31. Richard Vernon Sadleir (1722-1810) was a subscriber to Blair’s Grave in 1808 (“Richard Vernor [sic] Sadleir, Esq. Southampton”). On Sadleir’s friendship with Hayley, see Morchard Bishop, Blake’s Hayley: The Life, Works, and Friendships of William Hayley (London: Gollancz, 1951) passim. The verses bear the title “Palemon’s expostulations to his Looking Glass—inscribed to Miss Spilsbury which drew his Picture in the seventy six year of his age”: ↤ 32. Quoted in Young, Father and Daughter 18-19. The poem so resembles Hayley’s own occasional verse that one suspects he may have had a hand in it.

Cease, faithless Mirror, to persuadeThus we find the Spilsburys on the fringes of William Hayley’s circle, just three years before Blake was induced to settle at Felpham under Hayley’s patronage. begin page 103 | ↑ back to top

That I am old and coarsely made;

.......................................

Maria, if thy pencil thus can give

Beyond this poor Existence to survive,

Oh! Could my Verse thy Lovely Form shew forth,

Thy Manners gentle and thy modest Worth,

Melodious numbers should transmit thy Name

To shine distinguished in the Rolls of Fame!32

As early as 1761, Jonathan had been engraving in mezzotint, mostly copies of portraits by other hands.33↤ 33. Spilsbury’s engraved portraits are listed in John Chaloner Smith, British Mezzotinto Portraits: Being a Descriptive Catalogue of These Engravings from the Introduction of the Art to the Early Part of the Present Century, 4 vols. in 5 (London: H. Sotheran & Co., 1878-83); Charles E. Russell, English Mezzotint Portraits and Their States, from the Invention of Mezzotinting until the Early Part of the Nineteenth Century, 2 vols. (London: Halton & Truscott Smith; New York: Minton, Balch, 1926); [Freeman Marius O’Donoghue], Catalogue of Engraved British Portraits Preserved in the Department of Prints and Drawings in the British Museum, 6 vols. (London: Printed by Order of the Trustees, 1908-25). As his daughter’s fame grew, he seems to have given up painting entirely (like the Mr. Spilsbury that Blake met in 1804) and concentrated on mezzotint engraving while supporting his daughter’s career. Like Blake a decade later, by the 1770s Spilsbury was finding the London engraving market a more promising career move than chancing his luck exclusively in painting.

Jonathan Spilsbury and his brother John were the children of Thomas Spilsbury (1681-1741) of Worcester, whose second wife was Mary Wright (1718?-73) of Broadwas.34↤ 34. Young, Father and Daughter 5. John (1739-69) during his short life kept a print shop in Covent Garden, where he sold the work of both his elder brother (chiefly mezzotint portraits) and himself (principally maps). The identities of the two brothers are often confused—both signing their work “J. Spilsbury.” Jonathan Spilsbury was the engraver of A Collection of Fifty Prints from Antique Gems, in the Collections of the Right Honourable Earl Percy, the Honourable C. F. Greville, and T. M. Slade, Esquire . . . (London: John Boydell, 1785), but Boydell mistakenly printed John’s name on the title page.35↤ 35. Sloman, Oxford DNB entry. Jonathan was also responsible for an etching of the Moravian settlement at Bethlehem, Pennsylvania (illus. 2). Blake also worked for Boydell around this time, thus perhaps renewing his acquaintanceship with the Spilsbury family.36↤ 36. On Blake’s work for Boydell, see Robert N. Essick, William Blake’s Commercial Book Illustrations: A Catalogue and Study of the Plates Engraved by Blake after Designs by Other Artists (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1991) 42-45. John Spilsbury styled himself an “Engraver and Map Dissector in Wood, in Order to Facilitate the Teaching of Geography,” and is credited with the invention of “dissected maps”—hand-colored maps, mounted on thin sheets of wood and cut into pieces according to the political borders of the region being mapped.37↤ 37. See Jill Shefrin, Neatly Dissected for the Instruction of Young Ladies and Gentlemen in the Knowledge of Geography: John Spilsbury and Early Dissected Puzzles (Los Angeles: Cotsen Occasional Press, 1999). He is sometimes regarded as the inventor of the jigsaw puzzle. John’s widow Sarah married Harry Ashby, with whom James Gillray (himself from a Moravian family) served his apprenticeship.38↤ 38. Richard Godfrey, James Gillray: The Art of Caricature (London: Tate Publishing, 2001) 12, 45. Godfrey’s description of Moravian church life during Gillray’s childhood as “austere and unattractive” and “grim” (12) misrepresents it entirely. David Erdman, in Blake: Prophet Against Empire, 2nd rev. ed. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969) 38, 214-21 argues that Blake followed Gillray’s career closely and was influenced by his style.

An elder half-brother, Thomas Spilsbury (b. 1733; d. 1 December 1795), was a printer in Holborn.39↤ 39. Confusingly, it seems that Jonathan Spilsbury had both an elder half-brother Thomas, born 1733, and a younger full brother Thomas, born about 1742. He was one of the first English printers to specialize in printing French books accurately, “even superior to Parisian printers.”40↤ 40. Maxted 212. The French texts printed by Thomas Spilsbury include Emanuel Swedenborg, Doctrine de la Nouvelle Jérusalem, touchant le Seigneur (Londres: T. Spilsbury, 1787), a translation by B. Chastanier of Doctrina Novae Hierosolymae de Domino. He is best known, or maybe notorious, as the printer of Payne Knight’s Account of the Remains of the Worship of Priapus.41↤ 41. Richard Payne Knight, An Account of the Remains of the Worship of Priapus, Lately Existing at Isernia, in the Kingdom of Naples: In Two Letters; One from Sir William Hamilton . . . to Sir Joseph Banks . . . and the Other from a Person Residing at Isernia: To Which Is Added a Discourse on the Worship of Priapus, and Its Connexion with the Mystic Theology of the Ancients (London: T. Spilsbury, 1786). His sons William and Charles succeeded their father at 57 Snow Hill, Holborn.

It seems that Jonathan and Rebecca Spilsbury made a joint application for reception into the Moravian congregation at Fetter Lane in August 1781: “The Candidates for Reception into the Congregation, still remaining on the List, Aug. 13. . . . are . . . Jonathan & Rebecca Spilsbury.”42↤ 42. Moravian Church Archive C/36/10/10 (Minute Book, 4 August 1781-31 December 1782), entry for 3 November 1781. Rebecca’s candidature was refused, and Jonathan Spilsbury alone was received into the Moravian church in November 1781. The Fetter Lane Church Book notes as follows: “Jonathan Spilsbury M[arried] B[rother] Ch. of Eng. Portrait Painter | [born] Worcester feb. 2. 1745. | [received] Nov: 11th 1781. | [first admitted to the Sacrament] March 28 1782 | Departed this life Oct 31st 1812. Buried in Bunhill Fields.”43↤ 43. Moravian Church Archive C/36/5/1 (Church Book no. 1), p. 52. I cannot explain the incorrect year of birth other than as a simple arithmetic error. In fact, Rebecca Spilsbury was refused admission to the Moravian congregation several times, and thus, although sympathizing with her husband, remained nominally Anglican.44↤ 44. Personal communication from Charlotte Yeldham, 19 July 2005. Their daughter Maria was confirmed a member of the Church of England at St. George’s, Hanover Square, on 30 April 1795.45↤ 45. Young, Father and Daughter 11-12.

The circumstances of Jonathan’s acceptance, and Rebecca’s refusal, as members to be received into the Moravian community are sufficient in themselves to remind us that spiritualities even within a marriage could remain friendly but diverse. Since Jonathan Spilsbury engaged in the same trade as Blake, it is not inconceivable that such arrangements would have been well known, even commonplace, amongst others in the late eighteenth-century engraving trade. One recalls from Blake’s reported deathbed conversation that during the course of discussing his last wishes, Mrs. Blake offered him a choice as to funeral arrangements; that begin page 105 | ↑ back to top

The Moravian church had open preaching services that anyone could attend and other meetings that were intended just for church members. Spilsbury had been a “constant hearer” since at least 1769. When, in 1781, Spilsbury was “received” into the church, that meant he took part in the whole range of services (with some exceptions) and was allotted to a “band” (in his case the married Brethren) which had its own “quarter hour” in which members could discuss spiritual matters privately. In 1782, he was admitted to Holy Communion, which was a special privilege, marking him as part of a spiritual élite: “A Letter was read from the mar. Br Jonathan Spilsbury for admission to the holy Communion.47↤ 47. Moravian Church Archive C/36/12/3 (Congregation Council Minutes 16 June 1778-21 November 1782) [loose sheets (C/36/12/3/12) for Wednesday 17 January 1782].

Admission to Communion was taken extremely seriously. When partaking of the Blessed Sacrament was announced, communicating members were expected to look into their hearts to see if they considered themselves worthy of that privilege. On occasion, the elders would intervene to withhold the Sacrament. In 1738, John Wesley and Benjamin Ingham, the Yorkshire evangelist, visited the Moravian community at Marienborn. Ingham was invited to partake of the Sacrament; Wesley was conspicuously excluded. The grounds the Brethren gave for their action was that he was homo perturbatus—that is, a disturbed man.48↤ 48. John R. Weinlick, Count Zinzendorf (New York: Abingdon Press, 1956) 143. Not long after he was back in England Wesley became critical of Zinzendorf and his Moravian followers and began going his separate way.

begin page 106 | ↑ back to topIn a curious parallel to Blake’s career in Felpham, Spilsbury while in Southampton had sought employment as a miniature painter.49↤ 49. BR(2) 104-07 records Hayley’s encouragement of Blake in the painting of miniature portraits. ↤ 50. Spilsbury’s letter to his wife (28 August 1798), quoted in Young, Mrs. Chapman’s Portrait 114. (Could Lady de Lally have lent part of her name to “Tilly Lally” in An Island in the Moon? The suggestion, made by Morton Paley in a private email, is certainly a provoking one.)

I am preparing an Ivory for a Miniature Picture and I find (what I formerly did) that after all the care taken in preparing Gum or Paste, to paste paper at the back of it, the Ivory appears cloudy and not of a very good colour, perhaps Mr. Cosway woud be so kind as to tell me how I should manage it, if I cou’d get the Ivory prepared to my wish my Miniatures woud be much better than I can otherwise do them. After Maria has seen Lady de Lally, I think I shall write to Mr. Cosway on the subject ....50This letter seems to imply that Spilsbury, like Blake, is a friend of Richard Cosway, the society painter and mystic. Cosway had been the young William Blake’s instructor at Pars’s Drawing School from 1767 to 1772, and became his lifelong friend. Cosway also had an enduring friendship with James Hutton, founder of the Fetter Lane Moravian church, and painted his portrait.51↤ 51. Now in Moravian Church House, 5-7 Muswell Hill, London N10 3TJ. A mezzotint engraving of this portrait, by J. R. Smith after Cosway, was published in 1786. On Cosway (1742-1821) and the Moravians, see John Nichols, Literary Anecdotes of the Eighteenth Century, 9 vols. (London: Printed for the Author, 1812-15) 3: 435-37. The simian-featured Cosway, it seems generally to be agreed, is satirized as “Mr. Jacko” in Blake’s An Island in the Moon, where it is noted that he and his wife “have black servants lodge at their house” (E 457).52↤ 52. A point originally made by Erdman in Blake, Prophet Against Empire 96. See also R. J. Shroyer, “Mr. Jacko ‘Knows What Riding Is’ in 1785: Dating Blake’s Island in the Moon,” Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly 12.4 (spring 1979) 250-56; Paul Edwards, “An African Literary Source for Blake’s ‘Little Black Boy’?” Research in African Literatures 21 (1990): 179-81. One of these black servants was the writer and campaigner Ottobah Cugoano.

In 1787, Blake engraved “Venus Dissuades Adonis from Hunting,” after Richard Cosway.53↤ 53. Number XXVIII in Robert N. Essick, The Separate Plates of William Blake: A Catalogue (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1983) 145-49 and plate 64. That year is also, I have suggested, the most plausible date for the writing of An Island in the Moon,54↤ 54. Alan Philip Keri Davies, “William Blake in Contexts: Family, Friendships and Some Intellectual Microcultures of Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century England,” diss., University of Surrey, 2003, 148. and is, coincidentally, the date of publication of a campaigning book by Cugoano.

Quobna Ottobah Cugoano, usually known by the shorter form Ottobah Cugoano, was born in present-day Ghana around 1757. Kidnapped and taken into slavery, he worked on plantations in Grenada before being brought to England, where he obtained his freedom. He was baptized as John Stuart—“a Black, aged 16 years”—at St. James’s Church, Piccadilly (the Blake’s parish church), on 20 August 1773.55↤ 55. Vincent Carretta, “Cugoano, Ottobah (b. 1757?),” Oxford DNB. While working as manservant to Richard Cosway, he wrote his Thoughts and Sentiments on the Evil and Wicked Traffic of the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species (1787). This work—part autobiography, part political treatise, and part Christian exegesis—has an enduring legacy as the first directly antislavery text written in English by an African.56↤ 56. Ottobah Cugoano, Thoughts and Sentiments on the Evil and Wicked Traffic of the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species: Humbly Submitted to the Inhabitants of Great Britain by Ottobah Cugoano, a Native of Africa (London: Printed in the year 1787). There are modern editions by Paul Edwards (London: Dawsons, 1969) and by Vincent Carretta (London: Penguin, 1999).

Spilsbury’s hopes of ordination as a Moravian minister were never realized.57↤ 57. Sloman, Oxford DNB entry. Such hopes indeed were perhaps impossible while his wife remained excluded from the congregation. He was, however, encouraged by the Moravian church as a preacher. Spilsbury’s obituary memoir in the Fetter Lane Congregation Diary refers to his involvement with the African Chapel in Peter Street, Soho. This seems to have been a special place of worship for African Christians in London.

↤ 58. Moravian Church Archive C/36/7/31 (Congregation Diary vol. 31: 10 September 1810-31 December 1816) [unnumbered pages for October 1812].His [Spilsbury’s] character among us was that of an humble, steady disciple of Jesus, whose heart was truly attached to him & his cause. It was his delight to invite sinners to Christ, & to testify unto them of his redeeming love. Thus in our Chapel here & in Chelsea, also at the Chapel of the African & Asiatic Society, in Peter Street, Soho, he has been engaged in labors of love of this kind, to edification. How much his heart was devoted to this employment may be gathered from the following in a Letter to Bt Montgomery of date Sept 1st this year.begin page 107 | ↑ back to top

“Next Sunday it has been expected that I should preach to the Africans who assemble in Peter Street but this my present indisposition obliges me to decline. If You should on that day be at liberty to supply my place in inviting, at least, I suppose forty or fifty Africans & other persons who attend at the same time, to partake of redeeming love I should be extremely gratified, & I am persuaded You would enjoy a blessing in the opportunity if You can embrace it.—

“As we have Missionaries in Africa and You are well acquainted with the success attending their labors in that part of the World, You would have it in your power to communicate many things, which would afford pleasure & encouragement to the members of the African Society in London;—If You cannot preach to them, perhaps some one of our other Labourers, now in London, may be disposed to embrace this opportunity of publishing the Glad Tidings of the Gospel.58

Could Spilsbury then have known Cugoano, perhaps through his involvement with this Chapel of the African and Asiatic Society?59↤ 59. The African and Asiatic Society had been set up around 1805 with William Wilberforce as president and Zachary Macaulay as treasurer “for the benefit of the poor natives of Africa and Asia and their descendants residing in London and its vicinity, to relieve their ignorance as well as the accumulated distress of poverty, nakedness, hunger, and sickness” (Times 6 July 1819, page 2 column A [classified advertising]). The African Chapel in Peter Street, Soho, seems to have been a former Church of Scotland building before it was used by the African congregation, and after 1820 or thereabouts it was used by the Methodists. This transfer of licensed dissenting meeting houses from one sect to another was not uncommon; the Moravians’ Fetter Lane church was previously used by Thomas Bradbury’s Independent congregation.60↤ 60. Colin Podmore, The Fetter Lane Moravian Congregation, London 1742-1992 (London: Fetter Lane Moravian Congregation, 1992) 3. Peter Street is connected to Broad Street (with the Blake family home at no. 28) by Hopkins Street, where the black ex-slave Robert Wedderburn had his Unitarian Chapel in a former hayloft.61↤ 61. On Wedderburn, the former slave turned preacher (father a Scot, mother a slave in Jamaica, came to Britain c. 1790, linked to the Spenceans in the late 1810s, jailed in 1821 for blasphemy), see Iain McCalman, Radical Underworld: Prophets, Revolutionaries and Pornographers in London, 1795-1840 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988) and David Worrall, Radical Culture: Discourse, Resistance and Surveillance, 1790-1820 (New York: Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1992). How many of the African churchgoers may have moved around the corner to form Wedderburn’s congregation?

It is worth noting here possible sources of Blake’s ideas of Africa and Africans. Blake would probably have known Ottobah Cugoano through his friendship with Cosway. Paul Edwards points out that Cugoano was “one of the leaders, with his friend Olaudah Equiano, of the London black abolitionists, an active radical group which corresponded with Granville Sharp and published letters to the press under the name ‘the Sons of Africa,’ Cugoano signing with his ‘English’ name, John Stuart.”62↤ 62. Edwards 181. Other Blake scholars have drawn our attention to the so-called St. Giles’ blackbirds, poor loyalist African former naval servicemen from the American War, who were often seen in the streets of London; their poverty was a visible social problem. But the African Chapel in Soho, a specifically Christian context for Africans in London (and very near to Broad Street where James Blake had his hosier’s shop), sheds a new light on Blake’s antislavery views, and on the strong religious feeling of “The Little Black Boy”:

And we are put on earth a little space,

That we may learn to bear the beams of love,

And these black bodies and this sun-burnt face

Is but a cloud, and like a shady grove. (E 9)

Rebecca Spilsbury died in February 1812 and was buried in Bunhill Fields. The Gentleman’s Magazine records: “In London, deeply lamented, Mrs. Spilsbury, eldest daughter of the late Rev. Dr. Chapman, Prebendary of Bristol Cathedral and master of St. John’s Hospital, Bath.”63↤ 63. Gentleman’s Magazine 82 (April 1812): 397. Strangely, it makes no reference to her husband. Jonathan Spilsbury survived his wife only until the following October, when he died aged 75, for he was eleven years older than Rebecca.64↤ 64. Young, Father and Daughter 30.

The Moravian Congregation Diaries record Spilsbury’s last illness—“[October 1812, Thursday] 29th We received information, late in the evening, that our dear & valuable Br Spilsbury, had been taken ill at the house of his Son in law, Mr Taylor, St George’s Row, N side of Hyde Park, & that he wished to be visited”65↤ 65. Moravian Church Archive C/36/7/31 (Congregation Diary vol. 31: 10 September 1810-31 December 1816) [unnumbered pages for October 1812]. —and then, the following day, his dying.

It is worth exploring in some detail here how the accounts given of William Blake’s death in 1827 appear to parallel much of the ceremony, observance, and spiritual validation in death which was commonplace in Moravian accounts of the “good death.” ↤ 66. Moravian Church Archive C/36/7/31 (Congregation Diary vol. 31: 10 September 1810-31 December 1816) [unnumbered pages for October 1812].

[Friday] 30th Early in the morning, Br Montgomery accordingly went thither, & found that he [Spilsbury] had been seized with a Paralytic Stroke, on Tuesday Evening last.—About two months ago he had had a slight affection [affliction?] of the same Kind, from which however, he soon recovered, & when he was with us the last time, at the H. Comn on Sept: 27th he was very lively & cheerful, & apparently in ye enjoyment of his usual state of health. From the very weak, enfeebled state in which he now was, it was evident the Stroke at this time must have been a very severe one. His whole frame appeared shattered & broken down, & there was but a faint hope, if any, of his surviving the shock it had received. So much the more comfortable was it to find that his Soul was cheered & comforted in an uncommon degree by the sweet presence & peace of God his Saviour. His speech, tho’ somewhat touched by the stroke, was still very intelligible, & his testimonies & declarations were of the most pleasing & edifying Kind. His confidence & his rejoicing in his Redeemer were without any thing either of wavering on the one hand, or of presumptuous boasting on the other. He spoke as a poor sinner that had found pardon & the forgiveness of sin in the blood of Jesus, & therefore now knew him in whom he believed, & rejoiced. He expressed his gratitude to our Savr shewn to him at this time in a lively manner, & said “How thankful might I to be to our Savr, who deals so graciously with me, that, notwithstanding all sickness & infirmity, I have neither any bodily pain, nor any anxiety of mind to trouble me.” Again he observed “How this sickness will end I know not, but, whether it be for life or death, this I know, that I shall be the property of Jesus, and that in his own time, he will come & fetch me:—those that are in Christ can never die, for he is the Resurrection & the life, and therefore I shall attain to Life eternal”. . . . After begin page 108 | ↑ back to top Br Montgomery, at his request, had prayed with him, a great number of his friends & Relations being present, he gave out the Verse “Praise God from whom all Blessings flow” &c & requested the whole company to join singing it, which was accordingly done.—About 9 O’Clock the same evening he fell asleep, and without waking again to the things of this vain world, his Soul passed over into the arms of its heavenly Bridegroom, about 5 O’Clock in the morning following. So the bitterness of death was taken away that he did not taste it. He was in the 76th year of his age.66Compare Alexander Gilchrist’s account of Blake’s death: ↤ 67. Gilchrist 1: 360-62.

The final leave-taking came he had so often seen in vision; so often, and with such child-like, simple faith, sung and designed. With the very same intense, high feeling he had depicted the Death of the Righteous Man, he enacted it—serenely, joyously. . . . “On the day of his death,” writes Smith, who had his account from the widow, “he composed and uttered songs to his Maker, so sweetly to the ear of his Catherine, that when she stood to hear him, he, looking upon her most affectionately, said, ‘My beloved! they are not mine. No! they are not mine!’” . . . To the pious Songs followed, about six in the summer evening, a calm and painless withdrawal of breath; the exact moment almost unperceived by his wife, who sat by his side. A humble female neighbour, her only other companion, said afterwards: “I have been at the death, not of a man, but of a blessed angel.”

A letter written a few days later to a mutual friend by a now distinguished painter, one of the most fervent in that enthusiastic little band I have so often mentioned, expresses their feelings better than words less fresh or authentic can. . . .

“Lest you should not have heard of the death of Mr. Blake, I have written this to inform you. He died on Sunday night at six o’clock, in a most glorious manner. He said he was going to that country he had all his life wished to see, and expressed himself happy, hoping for salvation through Jesus Christ. Just before he died his countenance became fair, his eyes brightened, and he burst out into singing of the things he saw in heaven. In truth, he died like a saint, as a person who was standing by him observed. . . .67

There are striking similarities: Spilsbury and Blake both die joyously and to the sound of hymns. Gilchrist’s account of Blake’s death has recently been deemed unlikely on medical grounds by Aileen Ward, and by Lane Robson and Joseph Viscomi.68↤ 68. Aileen Ward, “William Blake and the Hagiographers,” in Frederick R. Karl, ed., Biography and Source Studies (New York: AMS Press, 1994); Lane Robson and Joseph Viscomi, “Blake’s Death,” Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly 30.2 (fall 1996): 36-49. However, like the account given of Spilsbury’s death, it conforms closely to the customary Moravian trope of the good death, including the emphasis on singing at the point of death. Thus, when John Seniff, the German-born shoemaker who was Swedenborg’s friend in London, died on 2 May 1751, the Fetter Lane Congregation Diary reads: ↤ 69. Moravian Church Archive C/36/7/5 (Congregation Diary for the Fetter Lane Congregation vol. 5: 1 January 1751-31 December 1751), p. 31. On Seniff’s friendship with Swedenborg, see R. L. Tafel, ed., Documents concerning the Life and Character of Emanuel Swedenborg, Collected, Translated, and Annotated, 2 vols. in 3 (London: Swedenborg Society, 1875-77) 2: 586-87.

His last Sickness was short, (being the Gravel) & not so threatening in appearance as some he had before: When any visited him, he always testified with a peaceful Heart & Countenance the Satisfaction he felt in the Savr’s Love, & in the Hopes of going to Him; & the last Words he utter’d were the two concluding Verses of that German Hymn, “O Haupt voll Blut und Wunden,” which he began to sing of his own accord, & Br Hintz (his old Acquaintance, who also happen’d to lodge in his House) accompanied it by gently touching the Guitar; & directly he expired.69

Perhaps the most striking parallel to Gilchrist’s account occurs not in the Congregation Diaries but in David Cranz’s 1767 history of the Moravian mission in Greenland: ↤ 70. David Cranz, The History of Greenland, Containing a Description of the Country and Its Inhabitants, and Particularly a Relation of the Mission, Carried On for above These Thirty Years by the Unitas Fratrum at New Herrnhuth and Lichtenfels in That Country, 2 vols. (London: Printed for the Brethren’s Society for the Furtherance of the Gospel among the Heathen, 1767) 2: 148.

But the full grain that was sown in the earth this year, nay the first and hitherto only European helper in this mission was Mrs. Drachart, the wife of the Danish missionary. Towards the end of last year she was seized with a violent burning fever, soon after she came to live at New-Herrnhut. The first day of this year she was delirious, but it was of a lovely kind; she incessantly sung verses of her own composing, and that in such a coherent manner, as if she had been one of the most excellent poets. Towards night she was quite still, and in a short time afterward fell gently and happily asleep in the Lord, in the thirty-sixth year of her age. Her corpse was deposited in a walled sepulchre in the burying-ground at New-Herrnhut.70And when Maria (Spilsbury) Taylor died in Dublin on 1 June 1820, “with great self-control her husband sang a hymn beside her bed as she faded out of the world, for he remembered how she loved the United Brethren’s custom of singing whilst a spirit was passing.”71↤ 71. Young, Father and Daughter 35.

The Congregation Diary also contains a note on Spilsbury’s burial in Bunhill Fields: ↤ 72. Moravian Church Archive C/36/7/31 (Congregation Diary vol. 31: 10 September 1810-31 December 1816) [unnumbered pages for November 1812].

[November 1812, Saturday] 7th Agreeably to a request of our late Br Spilsbury, that his Corpse might be laid in the same grave with that of his Wife in Bunhill fields, & that he might begin page 109 | ↑ back to top be buried in the manner usual among the Brn, Br Montgomery accompanied his remains from St George’s Row thither, & kept the funeral—After a short address in reference to the solemn occasion & during the Reading of our Burial Litany, his mortal part was committed to the ground, to be quickened in due time by the Spirit of Jesus which had dwelt in it.72As a Moravian, Spilsbury would in the normal course of events have been laid to rest in the Moravian Burying Ground at Chelsea. However, husband and wife could be laid together in the same grave at Bunhill Fields, not separately, women apart from men, as was the Moravian custom.73↤ 73. Young, Father and Daughter 30.

Thus both Spilsbury and Blake are buried at Bunhill Fields, not out of sectarian conviction (the “Dissent” that preoccupies so many Blake scholars), but for simple family reasons: ↤ 74. Gilchrist 1: 361. See also my note 46 for an alternative citation.

A little before his death, Mrs. Blake asked where he would be buried, and whether a dissenting minister or a clergyman of the Church of England should read the service. To which he answered, that as far as his own feelings were concerned, she might bury him “where she pleased.” But that as “father, mother, aunt, and brother were buried in Bunhill Row, perhaps it would be better to lie there. As to service, he should wish for that of the Church of England.”74

Blake’s deathbed reference to his beloved younger brother reminds us of Gilchrist’s account of Robert’s own joyous end: “At the last solemn moment, the visionary eyes beheld the released spirit ascend heavenward through the matter-of-fact ceiling, ‘clapping its hands for joy’—a truly Blake-like detail.”75↤ 75. Gilchrist 1: 59. This finds a parallel in Draper Hill’s citation of an account of the death of James Gillray’s elder brother Johnny while at the Moravian school at Bedford: “‘Pray don’t keep me. O let me go, I must go—’ which were his last words.”76↤ 76. Draper Hill, Mr. Gillray the Caricaturist: A Biography (London: Phaidon Press, 1965) 12.

There is one last parallel to draw. The “Br. Montgomery” who attended Spilsbury’s deathbed and officiated at his burial in Bunhill Fields was the Rev. Ignatius Montgomery (b. 1776), younger brother of the Sheffield poet, journalist, hymn writer, and abolitionist James Montgomery (1771-1854). Bentley, in Blake Records, cites a letter of April 1807 from Robert Hartley Cromek to James Montgomery that “suggests a connexion between Blake and James Montgomery and Blake’s admiration for Montgomery as a ‘Man of Genius’, of which we should not otherwise have known.” The letter “implies an easy and personal contact between the two men.”77↤ 77. BR(2) 239. The letter is far too long to cite in its entirety and yet resistant to selective quotation. Indeed, “Mr. Montgomery, Sheffield” was one of the subscribers to Blair’s The Grave.78↤ 78. BR(2) 277fn. There are references to Blake’s Grave designs in Montgomery’s Memoirs, vol. 1 (London, 1854)—see G. E. Bentley, Jr., Blake Books (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1977) 835. James Montgomery included Blake’s “The Chimney Sweeper” from Songs of Innocence in his The Chimney-Sweeper’s Friend and Climbing-Boy’s Album (London: Longman, Hurst, etc., 1824) 343-44. Is it possible that, during the years 1804 to 1807 of Blake’s friendship with Spilsbury and Montgomery, when both men attended the services at Fetter Lane, they may have taken Blake back to his mother’s former church?79↤ 79. A suggestion made by Marsha Keith Schuchard in her paper “Young William Blake and the Moravian Tradition of Visionary Art” [in this issue—Eds.].

Spilsbury and Blake, two deeply religious men, would have met at the Royal Academy Schools, and later as engravers working for Boydell. Both had had experience of running printshops, Spilsbury with his brother until John’s death in 1769, Blake in partnership with James Parker from 1784 to 1785.80↤ 80. BR(2) 33-34. Both left London to find work elsewhere, and were reduced to the mundane work of provincial miniature portrait painters. Both were friends with the Montgomery brothers, prominent members of the Moravian church. The accounts of their deaths, as steadfast, virtuous, and joyful ends witnessed and recorded by friends, follow a very similar pattern, as do their eventual burials in Bunhill Fields.

The years when Blake’s mother worshipped at Fetter Lane constitute a period of great creativity in the life of the Moravian church, in terms both of its theology and of its liturgy and ritual. The Fetter Lane Congregation Diaries contain an account of an adult baptism, that of Sister Jane James: ↤ 81. Moravian Church Archive C/36/7/3 (Diary of the Congregation at London, for the Year 1749), p. 115 [November].

[13 November 1749] . . . the Floor being covered with a white Cloth, & the Vessel of Water brought in by 2 Sisters, (one of whom had herself been baptized when an Adult) the Candidate also approached in a white Dress made for the purpose, the Hem or Guard of which was red, & a red Streak from the Throat down to the Feet; then Br B[oehler] first, with several of the Sister-Labourers, laid the Hand on her Head, under that Verse, “Where agonizing Blood,” &c. and afterwards baptized her in a very solemn Manner by the Name of Anna.81In the account of the baptism of Jane James, the red ribbon running from the throat down to the feet symbolizes the cleansing blood of the Savior. I suggest that William Blake’s Moravian inheritance runs like such a crimson ribbon throughout his life from his mother’s first involvement with the Moravian church even to his death. Or, to put it more prosaically, I suspect that the Blake family’s involvement with the Moravian church extended long after Catherine had supposedly left the congregation, and if not persisting throughout Blake’s life, certainly seems to have been renewed after 1800.