ARTICLE

Mark and Eleanor Martin, the Blakes’ French Fellow Inhabitants at 17 South Molton Street, 1805-21

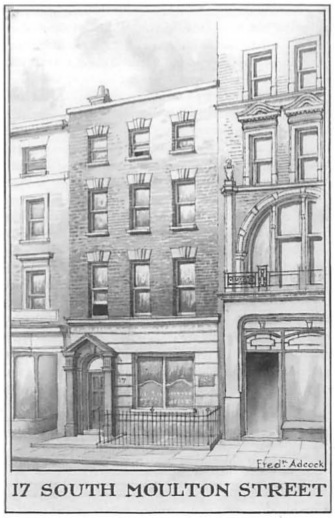

As the first major Paris exhibition of the poet-artist’s works in over sixty years has recently taken place,1↤ 1. William Blake, le génie visionnaire du romantisme anglais, Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris, Apr.-June 2009. it seems fitting to discuss William and Catherine Blake’s sixteen-year association with a Parisian: their landlord at 17 South Molton Street, Mark Martin. In this paper, after a brief discussion of his predecessors, I present new information concerning Martin, his wife, his nationality, and his trade. I also discuss the relationship between the Martins and the Blakes and how the nature of that relationship throws light on the Blakes’ seventeen-year residence in South Molton Street (illus. 1-2), a period of Blake’s life of which we still know very little.

Mark Martin is at least in name not unfamiliar to Blake scholarship. In April 1830, almost three years after Blake’s death, John Linnell recalled: “When I first became acquainted with Mr. Blake he lived in a first floor in South Molton Street and upon his Landlord leaving off business & retiring to France, he moved to Fountain Court Strand, where he died.”2↤ 2. Letter to Bernard Barton, quoted in Bentley, Blake Records [hereafter BR(2)] 526. Alexander Gilchrist states in his 1863 biography that the move to Fountain Court occurred in 1821 (Gilchrist 282). In 1958 Paul Miner, on the basis of data from early nineteenth-century rate books for the parish of St. George, Hanover Square, first identified “the rate-payer [at 17 South Molton Street] for the period 1803-1821, presumably Blake’s landlord,” as Mark Martin.3↤ 3. Miner 544. Although most subsequent biographers have utilized Miner’s discovery, none has expanded upon it. Martin has remained no more than a name, referred to as “Mark Martin,” “one Mark Martin,” or “a certain Mark Martin.”4↤ 4. See respectively Bentley, Stranger 260fn, King 158, Ackroyd 249. Commenting upon Linnell’s recollection, Miner observed that, although Martin appears to have retired to France in 1821, “he seems to have retained ownership of the property; at any rate a ‘Mark Martin’ continued to pay the rates as late as 1829.”5↤ 5. Miner 544. He thanks “G. F. Osborn, Archivist, Westminster Public Libraries, for this information” (549n32). No subsequent biographer has discussed Martin or identified the business he must have left off in order to retire. Ruthven Todd observed that “it is not known whether the ground floor [of no. 17] was then used commercially as it has been for at least a century.”6↤ 6. Todd 63. However, Peter Ackroyd first suggested that the Blake’s two rooms would have been situated “no doubt above some kind of commercial establishment.”7↤ 7. Ackroyd 248-49. In this essay I demonstrate that both Miner and Ackroyd were correct.

The Blakes’ Previous Landlord(s?) at South Molton Street: John Lytrott

However, Miner is mistaken in some details. Martin was not ratepayer (and consequently not landlord) at 17 South Molton Street between 1803 and 1804, when William and Catherine Blake first lodged there; he was their second or perhaps third landlord at this residence. The ratepayer in March 1803 is recorded as John Lytrott,8↤ 8. St. George’s Parish, Hanover Square, Brook Street Ward, poor, watch, and paving rates, 1803 (City of Westminster Archives Centre [hereafter COWAC] C596). and the residential section of Holden’s Triennial Directory lists a Captain John Lytrott.9↤ 9. Holden’s Triennial Directory 1802-03-04 (1802) n. pag. It is therefore possible that the Blakes initially corresponded with, met, and even lodged briefly with Lytrott between his last appearance in the rate book in March 1803 and his absence therein the following year. Since the Blakes moved in about October 1803,10↤ 10. See Erdman [hereafter E] 737 (letter of 26 Oct. 1803). However, the South Molton Street address on this letter is in fact an insertion by Gilchrist (see Gilchrist 170). A letter of 7 Oct. 1803 suggests that the Blakes had only recently arrived in London (E 736-37). Lytrott may have been their landlord (if not necessarily their fellow inhabitant) for a period of up to five and a half months.11↤ 11. Several facts concerning Lytrott’s life can be traced. He was baptized in 1763 at St. George’s Church, Hanover Square (International Genealogical Index <http://www.familysearch.org>), so was almost certainly born and bred in Mayfair. However, his name and choice of regiment suggest Scottish ancestry. On 19 Dec. 1777 he was commissioned as quartermaster for the first battalion of Major-General John Mackenzie, Lord Macleod’s Highlanders, Seventy-Third Regiment, a Scottish regiment raised in response to the outbreak of the American war (see A List of the General and Field Officers, As They Rank in the Army [Dublin: Executors of David Hay, 1780] 148). The Seventy-Third served in southern India and sustained heavy losses at Cuddalore on 13 June 1783. In 1784 Lytrott appears in the army lists as second lieutenant (a commission almost certainly purchased) in the Royal North British Fusiliers, Twenty-First Foot. However, the entry indicates that he was collecting half pay, which suggests that he had retired or was unfit for active service (A List of the Officers of the Army... Complete to 1st June 1784 [Dublin: Abraham Bradley King, 1784] 294). Lytrott’s listing in a new regiment and on half pay shortly after the battle of Cuddalore, coupled with his later appointment as captain of the Seventh Royal Veterans, a regiment for servicemen unfit for active duty (see below), implies that he was wounded or incapacitated during his service in India.

On 17 May 1788, after partially retiring from the army, Lytrott married Ann MacDonald at St. George’s, Hanover begin page 85 | ↑ back to top

Whether Lytrott’s wealth derived from his wife or was his own, he appears to have been a man of some means, leaving begin page 86 | ↑ back to top generous sums to servants on his death in 1809.16↤ 16. He bequeathed Eleanor Ryan £500 and Thomas Branning “my servant and a private soldier in the Seventh Royal Veteran Battalion fifty pounds together with all my shirts and wearing apparel except my regimental cloak boots and accoutrements ... ” (will of John Lytrott of Hanover Square, Middlesex, proved 17 July 1809 [PRO PROB 11/1501, Prerogative Court of Canterbury Will Registers, Loveday Quire Numbers: 560-617]). According to his will, Lytrott was living in Lower Swan Street, Chelsea, by 1809. This suggests that these servants had been employed for several years and had therefore lived at South Molton Street five years earlier. Lytrott also bequeathed £100 to his stepdaughter, Mrs. Christian Hargreaves, née MacDonald. His evident wealth indicates that no. 17 was the well-kept home of a man of substance.

MacDonald and Lytrott describe themselves in their wills as gentlemen and as resident or formerly resident at South Molton Street. This may suggest that during the residence of both men, and probably since its construction (c. 1755), no. 17 served the purpose for which it was built: to accommodate one household. However, it is also possible that a shopkeeper or lodger may have rented a floor. Nevertheless, from the time that the house was built until the Blakes’ arrival, persons of social rank paid the rates. From March 1804 until several decades after the Blakes left, the ratepayers were tradesmen, indicating a social shift in the history of the house.17↤ 17. In the 1861 census William Arnold, breeches maker, is listed as residing and trading at no. 17 (PRO RG9/93/4-15); in 1868 a Mrs. Dodkin, private resident, is recorded as living there (Kelly’s London Directory 1868 [n. pag.]).

The Blakes’ Previous Landlord(s?) at South Molton Street: William Enoch

A ratepayer at no. 17 who we can be certain preceded Martin as the Blakes’ landlord and fellow inhabitant is William Enoch, who ran a tailor’s shop from this address, presumably on the ground floor. Rate-book entries indicate that he assumed the rates as Lytrott ceased paying and in all probability left the premises, i.e. between March 1803 and March 1804. Enoch lived with his wife, Mary Naylor Enoch, and their infant son, William, above the shop.18↤ 18. For further details, see Whitehead, “New Information.” In a letter of January 1804, written after his trial for sedition at Chichester, Blake informed William Hayley, “my poor wife has been near the Gate of Death as was supposed by our kind & attentive fellow inhabitant. the young & very amiable Mrs Enoch. who gave my wife all the attention that a daughter could pay to a mother.”19↤ 19. E 740. This implies extremely amiable relations between the Blakes and the Enochs, perhaps suggesting that they remained friends after the family left no. 17.20↤ 20. This may strengthen Bentley’s suggestion that there is a connection between the Enochs and Blake’s lithograph Enoch (see BR(2) 750). However, the business appears to have been experiencing difficulties by the closing months of 1804, necessitating the Enochs’ departure from the shop and apartment, certainly by March 1805 and perhaps as early as the autumn of 1804. As Mary Enoch had provided aid and solace to Catherine Blake in early 1804, the Blakes may have tried to assist their co-inhabitants at the end of that year as the business went under.

Entries from the London Gazette and Jackson’s Oxford Journal during the first half of 1805 explain the brief duration of the Enochs’ residence.21↤ 21. References to Enoch’s bankruptcy in the press consistently use an alternative spelling of his surname: Enock. In addition, his business is described as that of “Tailor, Dealer and Chapman.” The Gazette for 22 January 1805 indicates that by this date Enoch had already ben declared bankrupt. The fact that he is referred to as “late of 17 South Molton” suggests that the family had left by the end of 1804. However, no new address is mentioned. The same article reveals that Enoch had been ordered to surrender himself to the commission at Guildhall for examination on 5 and 9 February and 9 March to “make a full Discovery and Disclosure of his Estate and Effects.”22↤ 22. London Gazette 22 Jan. 1805: 118. On Saturday 2 February Jackson’s Oxford Journal included Enoch in a list of bankrupts: “William Enock ..., late of South Molton Street, Oxford Street, Middlesex, Tailor, February 5, 9, March 9 at Guildhall.”23↤ 23. My thanks to Keri Davies for bringing this reference to my attention. The settling of Enoch’s affairs before the issuing of a certificate of bankruptcy must have taken longer than anticipated, as proceedings were adjourned on 9 March 1805 and reconvened on the 23rd at a meeting in which final creditors proved their debts.24↤ 24. See London Gazette 9 Mar. 1805: 324. On 14 May the Gazette reported: ↤ 25. London Gazette 14 May 1805: 665.

Whereas the acting Commissioners in the Commission of Bankrupt awarded and issued forth against William Enock, late of South-Molton-Street, Oxford-Street, in the County of Middlesex, Tailor, Dealer and Chapman, have certified to the Right Honorable John Lord Eldon, Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, that the said William Enock hath in all Things conformed himself according to the Directions of the several Acts of Parliament made concerning Bankrupts; This is to give Notice, that, by virtue of an Act passed in the Fifth Year of His late Majesty’s Reign, his Certificate will be allowed and confirmed as the said Act directs, unless Cause be shewn to the contrary on or before the 8th Day of June next.25

Mark Martin

The rate-book entries for no. 17 reveal that Martin was first recorded as ratepayer in March 1805, approximately eighteen months after the Blakes moved into their lodgings.26↤ 26. St. George’s rates, 1805 (COWAC C598). However, it is possible that he had replaced the bankrupt Enoch as landlord and ratepayer as early as the autumn of 1804. Miner’s statement that “a ‘Mark Martin’ continued to pay the rates as begin page 87 | ↑ back to top

The change in ratepayer and business proprietor’s name from Martin to Martin and Stockham c. 1821 suggests that, as Linnell claimed, Martin retired to France. However, his retention in the new name of the firm implies either that he remained a (silent?) partner of Stockham’s or that Stockham agreed to take on his name.33↤ 33. Alternatively, Martin may have employed a relative to co-run the business in his absence. This information is significant, as it appears to be the sole contemporary evidence to support Gilchrist’s undocumented claim, followed by subsequent biographers, that the Blakes moved to Fountain Court, Strand, in 1821. However, Mark Martin’s trade, rather than his lodgers, would have been his principal source of income;34↤ 34. “A tradesman in London ... expects to maintain his family by his trade, and not by his lodgers” (Adam Smith, quoted in Schwarz 325). its significance should be explored.

A staymaker made, fitted, and sold stays, essentially a laced underbodice or corset stiffened by the insertion of strips of whalebone (see cover illus.). R. Campbell, writing about 1747, observed that

The Stay-Maker ... ought to be a very polite Tradesman, as he approaches the Ladies so nearly; and possessed of a tolerable Share of Assurance and Command of Temper to approach their delicate Persons in fitting on their Stays, without being moved or put out of Countenance. He is obliged to inviolable Secrecy in many Instances, where he is obliged by Art to mend a crooked Shape, to bolster up a fallen Hip, or distorted Shoulder. ... After the Stays are stitched, and the Bone cut into thin Slices of equal Breadths and the proper Lengths, it is thrust in between the Rows of Stitching: This requires a good deal of Strength, and is by much the nicest Part of Stay Work; there is not above one Man in a Shop who can execute this Work, and he is either Master or Foreman, and has the best Wages. When the Stays are boned, they are loosly [sic] sewed together, and carried Home to the Lady to be fitted ....↤ 35. Campbell 224, 225-26. In 1737 Samuel Johnson had “take[n] humble lodgings with a staymaker named Richard Norris just off the Strand” (see Rogers). Blake’s friend Tom Paine was a trained staymaker (Keane 30). Joseph Taylor, father of Blake’s acquaintance Thomas Taylor the Platonist, was a staymaker at Round Court, St. Martin’s-le-Grand (see Louth).

This is a Species of the Taylor’s Business, and rather the most ingenious Art belonging to the Mechanism of the Needle. The Masters have large Profits when they are paid ....35

Martin’s shop, like all London shops of the period, probably kept long hours, possibly from 7.00 in the morning until 10.30 in the evening.36↤ 36. See George 206. However, such a trade as staymaking in Mayfair was dependent upon the fashion seasons and seasonal work, with a discrepancy between a brisk time of full employment, pressure of too much work, and long hours during the London season from late November to July, and a slack time with little or no work from the end of the London season until late autumn.37↤ 37. George 209, 263. One might draw a parallel between Martin’s capricious schedule of work (ebbing and flowing according to the London season) and Blake’s experiences as a commercial engraver during a period (post 1804) in which he appears to have been neglected in favor of the “softer” style of engravers such as Caroline Watson. Martin, like Blake, probably chose to trade in Mayfair for a reason, as explained by one of Blake’s visitors at South Molton Street, Robert Southey.38↤ 38. See BR(2) 310. About 1800 Southey wrote: ↤ 39. Quoted in Porter 118.

There is an imaginary line of demarcation which divides [Westminster and London] from each other. A nobleman would not be found by any accident to live in that part which is properly called the City ... whenever a person says that he lives at the West End of the Town, and consequently he is supposed to make my coat in a better style of fashion: and this opinion is carried so far among the ladies, that if a cap was known to have come from the City, it would be given to begin page 89 | ↑ back to top my lady’s woman, who would give it to the cook, and she perhaps would think it prudent not to inquire into its pedigree.39

As most women wore stays or corsets of some form or another during this period, staymaking was a well-established and popular trade. Martin’s business probably thrived particularly during the second half of the Blakes’ residence at no. 17, as a change in fashion prompted a renewed demand for stays. In the 1790s many liberals had expressed reservations about the fashion: Anna Laetitia Barbauld condemned stays in her letter “Fashion, A Vision,” published in the Monthly Magazine in April 1797, describing them as “the most common, and one of the worst instruments of torture, ... a small machine, armed with fish-bone and ribs of steel, wide at top, but extremely small at bottom. ... this detestable invention....”40↤ 40. McCarthy and Kraft 287. Frances Burney, visiting Paris in 1802, incredulously remarked “STAYS? every body has left off even corsets!”41↤ 41. Quoted in Ribeiro 94. Rousseau’s tomb featured “a number of naked children burning women’s whalebone stays.”42↤ 42. Ribeiro 4. Valerie Steele has observed that “throughout its history, the corset was widely perceived as an ‘instrument of torture’ and a major cause of ill health and even death. ... But the corset also had many positive connotations—of social status, self-discipline, artistry, respectability, beauty, youth, and erotic allure.”43↤ 43. Steele 1. Steele recounts the reemergence of stays as fashionable women’s undergarment during the first decade and a half of the nineteenth century: ↤ 44. Steele 33.

After a brief interregnum around 1800, the boned corset not only reappeared but spread throughout society. We might have expected that having once loosened their stays, women would never again wear corsets. Yet they did, in greater numbers than ever before. At the end of the Napoleonic Wars, in 1814 and 1815, the fashion for high-waisted “empire” gowns was waning. As the waistline on fashionable dresses began to drop to its normal position, skirts became fuller and boned corsets increasingly reappeared. Already by 1811, a writer for The Mirror of the Graces was predicting a return to tight-lacing, “Deformity once more drawing the steeled boddice [sic] upon the bruised ribs.” The fashion for neoclassical dress and no stays was regarded, in retrospect, as having been part and parcel of the disorder and promiscuity of the Revolutionary era. For the next century, boned corsets were an essential component of women’s fashion.44Further evidence of the increasing popularity of stays is revealed by the fact that Martin appears to have experienced competition from another staymaker’s shop in South Molton Street from c. 1816 onwards.45↤ 45. Although he lodged in Charles Street, William Bridges (or Brydges) rented a ground floor for his staymaking shop at “34 South Moulton Street” from Robert Gould. See Proceedings of the Old Bailey: trials of John Williams for “burglariously breaking and entering the dwelling-house of William Brydges,” 3 Apr. 1816, ref. t18160403-9, <http://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?ref=t18160403-9>. The address of his business is given in Pigot & Co.’s Directory 1823-24 (1823) 593. Brydges’s shop, on the same side of the street as Martin’s, would have been closer to the fashionable thoroughfare of Oxford Street at the heart of “the greatest Emporium in the known world” (national census [1801], quoted in Porter 123).

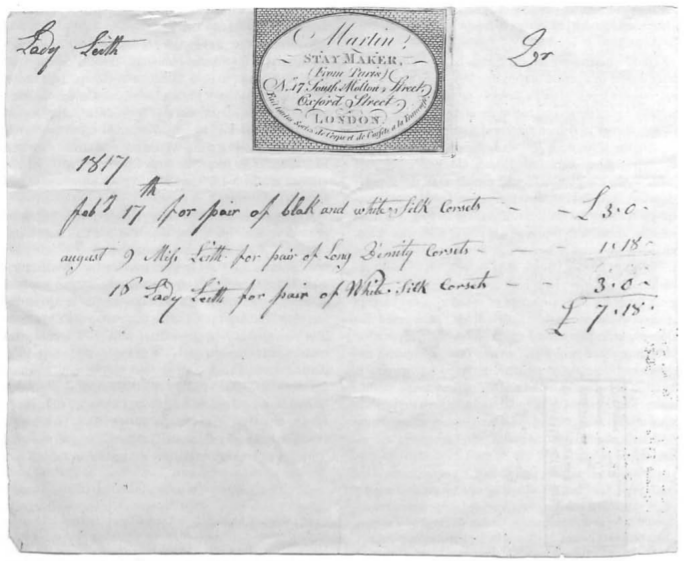

Some indication of the quality of Martin’s Mayfair customers survives in the form of a bill (illus. 4) to the recently widowed Lady Augusta Leith, daughter of George, fifth earl of Granard, and widow of the late Lieutenant-General Sir James Leith.46↤ 46. See Townend 1488 and Chichester. Sir James Leith of Leith Hall, Aberdeenshire, governor of Barbados and commander of the forces of the Windward and Leeward Islands, died of yellow fever in Barbados on 16 Oct. 1816. His will, written on the day he died and proved 27 Mar. 1817, left all his possessions to Lady Augusta and their children (PRO PROB 11/1590, Prerogative Court of Canterbury Will Registers, Effingham Quire Numbers: 106-66). His remains were interred in Westminster Abbey in Mar. 1817. Martin’s bill suggests that he produced luxury corsets for the aristocracy and gentry. Numerous other fashionable female and possibly male Westminster residents must also have called at his shop. The three separate transactions may indicate that Lady Leith and her daughter were regular customers.

At the head of the bill is a copperplate intaglio engraving printed in black ink giving details of Martin’s staymaking business.47↤ 47. The rectangular platemark measures approximately 47 mm. x 65 mm. The design is not stylistically distinctive, and there is no evidence that Blake ever produced such engraved tradesmen’s bills.48↤ 48. The nearest surviving equivalents are Blake’s engraving of an advertisement for Moore & Co. (1797) and the bookplate/calling card for George Cumberland (1827), far more ambitious projects with scope for Blake to exercise his own ideas (see BR(2) 819, 823). Therefore, it is likely that the stamp was engraved and printed for Martin by a professional writing engraver, such as William Staden Blake. However, the ink on the edge of the platemark on the top right and lower right corners might suggest that this was not the work of a general plate printer. No watermark is visible. However, it is also possible that Martin may have asked Blake to engrave and print this for him sometime before mid-February 1817. During this period the Blakes may have been glad of even such jobbing work. Details of Martin’s trade and address are engraved in an egg- or oval-shaped border and surrounded by a simple brickwork design: “Martin, / STAYMAKER, / (From Paris) / No. 17 South Molton Street, / Oxford Street, / LONDON. / Fait toutes Sortes de Corps et de Corsets a la Francoise.” (“makes all manner of French-style stays [or bodices] and corsets”). Martin’s use of the word “corps,” which translates roughly as “bodice” or “stays,” is of begin page 90 | ↑ back to top

I wish to thank Rory Lalwan for his assistance in tracing this document. It is clear from the bill that Martin had originally made it out for the first two corsets and then erased the original total, added the third purchase, and revised the total. On the verso “Lady Leith” is written in the same hand. Dimity, of which Miss Leith’s pair of long corsets was made, is a cotton fabric woven with stripes or checks. Ian Chipperfield, an authority on eighteenth- and nineteenth-century staymaking (see the Staymaker web site <http://www.thestaymaker.co.uk>), has not hitherto encountered references to black corsets in this period. He observes that the color is impractical as the undergarment would show through the outer garments (e-mail, 20 July 2005). However, the color may be connected with Lady Leith’s mourning for her husband and the burial of his remains at Westminster Abbey, which took place a few weeks after this purchase. A pair of corsets (as referred to in the bill) means in fact one corset, which was manufactured in two parts, later worn laced together.

Lady Leith Dr [?]

1817 feby 17th for pair of blak and white Silk Corsets — — £ 3.0 - august 9 Miss Leith for pair of Long Dimity Corsets — — — 1.18 - 16 Lady Leith for pair of White Silk Corsets — — 3.0 - £ 7.18.

at the beginning of the nineteenth century the Grecian figure—the natural figure (high rounded breasts, long well-rounded limbs)—was the ideal every woman hoped to attain. Her soft, light muslin dress clung to her body and showed every contour, so all superfluous undergarments which might spoil the silhouette were discarded—among them the boned stay. In France, where the social order had been completely overturned, with consequent loosening of morals and deportment, this fashion was more followed than in England. ... It is significant that in France the old name corps had quite disappeared, and from now on any tight-fitting body garment is known as a “corset”, a fashion that was copied in England though the old form “stays” was also retained.49In April 1816 Ackermann’s Repository of Arts noted: ↤ 50. Quoted in Waugh 100.

We have been favoured with the sight of a new stay, the “corset des Grâces”, which we understand has received very distinguished patronage. This stay possesses the double advantage of improving the shape, and conducing towards the preservation of the health; no compression, no pushing the form out of its natural proportions; it allows the most perfect ease and freedom to every motion, while, at the same time, it gives that support to the frame, which delicate women find absolutely necessary.50Such evidence suggests that, as the bottom had fallen out of the market for staymakers in the French capital, Martin may have migrated to London, where stays remained fashionable. This may have occurred c. 1800 (perhaps between the Treaty of Amiens of 25 March 1802 and Britain’s declaration of war on 18 May 1803), certainly by March 1805, the date of Martin’s first appearance in the rate books for no. 17.51↤ 51. According to Chipperfield, before the mid-1790s and after 1815 some London staymakers claimed to be French to attract a high-quality clientele (e-mail, 13 July 2005). However, of the numerous staymakers listed in London directories, few have French surnames. Two exceptions are Mes Dames Harman, 350 Oxford Street, and H. De Cleve, 5 Holywell Street, Strand (Pigot & Co.’s Directory 1823-24 [1823] 222). I have found no evidence of another staymaker with a recognizably French surname trading in Mayfair c. 1790-1830. In addition, the bill suggests that Martin’s surname, and therefore the name of his business, was pronounced in the French rather than the English manner.52↤ 52. However, evidence from Martin’s marriage record suggests that he anglicized his name (see below). If this was the case, his surname may have been pronounced in the English manner. Finally, the new discovery helpfully supplements Linnell’s claim that the reason for the Blakes’ leaving South Molton Street was “his Landlord leaving off business & retiring to France.” It appears that by the spring of 1821 Martin was returning as well as retiring to France and very probably to Paris, his former residence, if not the city of his birth.

At his shop Martin probably employed several assistants to attend customers in the ground-floor front room or to bone and sew stays and corsets in the back room. The basement may also have served as another workshop as well as store-room. Martin may have spent some time away from no. 17, calling upon genteel customers such as Lady Leith for a last fitting before their stays were finished at the shop. His business was just one of the numerous “brilliant and fashionable” shops in South Molton Street and the surrounding Mayfair streets selling luxury items.53↤ 53. See Pigot & Co.’s Directory 1823-24 (1823) 15. These included John Bruckner, ladies’ shoemaker, at no. 52, Heron and Jones, tailors, at no. 58, I. and J. Hunt, hatters, at no. 22, William Keith’s china and Staffordshire warehouse at no. 44, James Lay, hatter, hosier, and glover, at no. 22, and Francis Perico, surgeon, apothecary, and midwife, at no. 29.54↤ 54. See Whitehead, “New Discoveries” 2: 326-30. Such businesses substantiated the contemporary claim that in London, “the first city of the world,” “shops are unrivalled for splendour, as well as for their immense stocks of rich and elegant articles.”55↤ 55. Pigot & Co.’s Directory 1823-24 (1823) 15. In 1818 the Ladies’ Monthly Museum featured two fashionable dresses, a ball dress and a walking dress, designed by a Miss Macdonald of no. 50, which was opposite no. 17 (Ladies’ Monthly Museum Mar. 1818: 169-70). Perhaps Miss Macdonald was a relative of Ann and Christian MacDonald, wife and stepdaughter of John Lytrott.

Martin’s conducting a staymaker’s business may also be pertinent in the light of two examples of Blake’s minor verse from the period. Blake makes references to stays in annotations to his copy of volume one of The Works of Sir Joshua Reynolds (1798). On pages xiv-xv of his introductory “Some Account of the Life and Writings of Sir Joshua Reynolds,” Edmond Malone quotes Reynolds describing how, on a visit to the Vatican, he was “disappointed and mortified at not finding [him]self enraptured with the works of [Raphael] ....”56↤ 56. Reynolds is alluding to Raphael’s frescoes in the Stanze, which he encountered in 1750. Blake responds: ↤ 57. E 637. For Blake’s unfavorable comparison of Rubens to Raphael, see E 513-14.

I am happy I cannot say that Rafael Ever was from my Earliest Childhood hidden from Me. I saw & I Knew immediately the difference between Rafael & RubensHere Blake appears to be criticizing Reynolds’s evident inability to distinguish between Raphael’s and Rubens’s paintings.58↤ 58. Elsewhere Blake comments that Reynolds’s “Praise of Rafael is like the Hysteric Smile of Revenge” (E 642). However, in the fourth discourse, Blake also refers to stays in an annotation signaling approval of Reynolds’s criticism of the Venetian school—Titian, but more particularly Paolo begin page 92 | ↑ back to top Veronese and Tintoretto. On page 98 Reynolds states, “it appears, that the principal attention of the Venetian painters, in the opinion of Michael Angelo, seemed to be engrossed by the study of colours, to the neglect of the ideal beauty of form ...”59↤ 59. See Wark 66. On the opposite page, Blake writes: ↤ 60. E 651. This annotation appears to have been influenced by two earlier passages in the fourth discourse. On page 90 Reynolds asserts that “Carlo Maratti [thought] that the disposition of drapery was a more difficult art than even that of drawing the human figure ...,” to which Blake responds, “I do not believe that Carlo Maratti thought so or that any body can think so. the Drapery is formed alone by the Shape of the Naked [next word cut away in binding]” (E 650). On page 95 Reynolds writes, “Such as suppose that the great style might happily be blended with the ornamental, that the simple, grave and majestick dignity of Raffaelle could unite with the glow and bustle of a Paolo, or Tintoret, are totally mistaken,” to which Blake responds, “What can be better Said. on this Subject? but Reynolds contradicts what he says Continually He makes little Concessions, that he may take Great Advantages” (E 651). Blake appears to agree with Reynolds’s view that trying to ally the Roman ideal form with the Venetian school’s emphasis on costume is unsatisfactory. He plainly saw stays as an apposite image for the manipulation of the outline of the human form. It seems clear that he dislikes both stays and Venetian art for their immersion in and preoccupation with transient fashions rather than for any role they might have in idealization of form. Blake’s verse satirizes what he considers the artificial, ephemeral, and therefore inferior nature of Venetian painting, and the impossibility of uniting this style with the grand Roman style.

Some look. to see the sweet Outlines

And beauteous Forms that Love does wear

Some look. to find out Patches. Paint.

Bracelets & Stays & Powderd Hair57

If the Venetians Outline was Right his Shadows would destroy it & deform its appearance

A Pair of Stays to mend the Shape

Of crooked Humpy Woman:

Put on O Venus! now thou art,

Quite a Venetian Roman.60

Blake’s annotations of Reynolds have been dated c. 1798-1809 by David Erdman.61↤ 61. See E 886. This overlaps the period in which the Blakes lived above Martin’s staymaker’s shop. However, there are problems with Erdman’s dating. According to Bentley, “Blake’s annotations to Reynolds were probably written at two distinct periods, perhaps first about 1801-2 and second in 1808-9.”62↤ 62. Bentley, Blake Books [hereafter BB] 692. The annotations referring to stays, written in ink at first glance, appear to date from the second period.63↤ 63. See BB 693. However, those on pages xiv and xv were first written in pencil and then overwritten in ink.64↤ 64. Bentley indicates that pencil is overwritten in ink on p. xv (BB 693), but Erdman claims that the ditty on that page is in ink only (E 637). The underlying pencil may suggest that these annotations were part of the first round that Bentley dates to 1801-02, several years before Blake met Martin in late 1804-early 1805. But the dating of Blake’s annotations to Reynolds remains imprecise and inconclusive. It is therefore possibly that both references to stays date from 1805 on. Whether these references date from Blake’s period of residence with Martin or not, the perpetual presence of stays, instruments which for Blake hid and distorted the naked female form, may have served as a regular reminder of the “seducing qualities” and “Vulgar Stupidity” of the Venetian school.65↤ 65. Wark 67; E 651. Women in stays or corsets feature in Blake’s early engravings of designs by Thomas Stothard and others in the 1780s and early 1790s (see Essick, pls. 30, 32-34, 38, 39, 41, 43, 45, 54, 56, 103). However, in Blake’s illuminated works, female figures appear naked (see Visions of the Daughters of Albion pl. 3), in transparent and form-revealing clothes (The Marriage of Heaven and Hell pl. 2), or in fashionable free-flowing empire gowns (The Book of Thel pls. 2 and 4). As Blake wrote in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, “The nakedness of woman is the work of God” (E 36).

“A Frenchwoman”

Writing in 1927 of the Blakes’ residence in South Molton Street, Margaret Irwin wondered, “what did the landlady at Number 17 think of ‘them first floors’?”66↤ 66. Irwin 15. Commenting upon Linnell’s account of the “Landlord leaving off business & retiring to France,” Bentley observes that ↤ 67. BR(2) 750, quoting Gilchrist 350. In a footnote Bentley argues that the Frenchwoman’s advice was given before Apr. 1815, when George Cumberland, Jr., described The Last Judgment as “nearly as black as your Hat.”

it is tempting to speculate whether Martin retired to France because his wife was French, and, if she was, whether Blake was referring to her when he said of his fresco of “The Last Judgment”: “I spoiled that—made it darker; it was much finer, but a Frenchwoman here (a fellow lodger) didn’t like it.”67Blake’s statement derives from Gilchrist, who commented, “ill-advised, indeed, to alter colour at a fellow lodger and Frenchwoman’s suggestion!”

The “Frenchwoman” may very well have been Martin’s wife. A Mark Anthony Martin, widower, married Eleanor Larché, spinster, on Tuesday 20 May 1806 at St. Mary’s Church, St. Marylebone Road (illus. 5).68↤ 68. St. Mary’s Church, parish of St. Marylebone, marriage register, vol. 131 (City of London, London Metropolitan Archives, and COWAC). The church, just two blocks north of Oxford Street, would have been, along with the parish church of St. George, Hanover Square, the nearest place of worship in which the inhabitants of South Molton Street could marry. The name Mark Martin appears rarely in contemporary directories or in the marriage registers of the two local churches. This point, coupled with the fact that this Mark Martin married a woman with a French surname, suggests that he and the Blakes’ landlord are one and the same.

Although Martin was an extremely common name in France during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, Larché was not. The name appears in genealogical records almost exclusively in the small town of Gignac, in the Hérault Valley in Languedoc. However, despite a search of the International Genealogical Index and church records held at the mairie in Gignac, the early life and subsequent history of begin page 93 | ↑ back to top

Although they were married according to the rites of the Church of England, still a statutory requirement in 1806, Eleanor and her husband appear to have been born in France and may have been of Huguenot descent. While the officiating curate, Benjamin Lawrence, anglicized her surname to Larchey on the marriage certificate, Eleanor retained the French spelling, Larché. In contrast her husband, probably baptized Marc Antoine Martin, seems to have anglicized his name. Among the Blakes’ neighbors there appear to have been a number of other French people or individuals of French descent. These included Louis Claude Augarde, a hairdresser and ratepayer at no. 3, E. Blondeel, embroiderer, at no. 52, James Mivart, haircutter and perfumer, at no. 5, Claude Olivier, merchant, at no. 10, L. S. O. Petit, also at no. 10, who about July 1806 composed, published, and sold from his residence Observations sur les moyens de perfectionner la tournure des jeunes demoiselles [Observations on the Means of Improving the Shape and Carriage of Young Women],71↤ 71. The work was advertised in the Morning Chronicle of 2 July 1806. A copy survives in the British Library. George Parvin, coal merchant, at no. 21, Frederick Fladong, wine merchant, at no. 28, John Periot, gentleman and hotelier, at no. 1, Robert Sabine, haircutter and perfumer, at no. 41, and George Saffery, music teacher, at no. 63.72↤ 72. See Whitehead, “New Discoveries” 2: 323-27. As noted above, some years after the Blakes’ departure the staymaker Charlotte Lohay, daughter of the artisan painter Ambroise Lohay, succeeded Martin as ratepayer.73↤ 73. Catherine Blake, née Boucher, is likely to have been of French Huguenot descent (BR(2) 1-2), and Blake’s brother James had been apprenticed to a Huguenot weaver, Gideon Boitoult (BR(2) 11-12). As early as 1780, Blake, along with two fellow artists, was arrested as a suspected French spy near Chatham docks (Bentley, Stranger 58-60). Gilchrist wrote that to Blake in the early 1790s, “the French Revolution was the herald of the millennium, of a new age of light and reason. He courageously donned the famous symbol of liberty and equality—the bonnet rouge—in open day, and philosophically walked the streets with the same on his head” (Gilchrist 81). On 19 Oct. 1801, five months before the signing of the short-lived Peace of Amiens, and while residing in Felpham, Blake had written to John Flaxman observing that Felpham was as near to Paris as to London, and adding “I hope that France & England will henceforth be as One Country and their Arts One ...” (E 718). In 1803-04, during his trial for sedition and as fears of French invasion were growing in England, Blake and his wife were accused of voicing support for Napoleon. Private John Scofield claimed that Catherine said “altho she was but a Woman she wod. fight as long as she had a Drop of Blood in her—to which the said Blake said, my Dear you wod. not fight against France—she replied, no, I wod. fight for Buonaparte as long as I am able” (BR(2) 160). Catherine is also recorded as having expressed pro-French sentiments to George Cumberland, Jr., at South Molton Street: in Apr. 1815, during the Hundred Days and six weeks before the battle of Waterloo, Catherine exclaimed, “if this Country does go to War our K—g ought to loose his head” (BR(2) 320). This remark has been interpreted as indicative of either Catherine’s madness or of Blake’s influence over her. Perhaps her impassioned utterance should be viewed in the context of the Blakes’ having lodged for the past decade in the house of a couple of French descent in a neighborhood with a significance French presence. As such, her remarks might be interpreted as a desire for peaceful coexistence between England and France. Blake advocates peaceful coexistence with France in his annotations to Malone’s preface to Reynolds’s Works (E 641). A sympathetic reference to France can be found in Jerusalem, a work composed and created during Blake’s residence at no. 17 (see Jerusalem 66:15, E 218).

begin page 94 | ↑ back to topBlake’s facility with languages was noted on more than one occasion. According to Gilchrist, “Blake, who had a natural aptitude for acquiring knowledge, little cultivated in youth, was always willing to apply himself to the vocabulary of a language, for the purpose of reading a great original author. He would declare that he learnt French, sufficient to read it, in a few weeks.”74↤ 74. Gilchrist 151. Bentley observes that “we know nothing else of his French except one use of it about 1808 in his Reynolds marginalia.”75↤ 75. BR(2) 400fn. On the contents pages of Reynolds’s Works, Blake transcribes several lines of Voltaire in French and comments upon them. The subject is Giovanni de Medici, Pope Leo X, the principal patron of Raphael. Hitherto this unique instance of Blake’s written use of French has received little attention. ↤ 76. The grammatically correct “le” is transcribed in Bentley, William Blake’s Writings 2: 1451. ↤ 77. E 636. The passage may be translated as: You can say that Pope Leo X, by encouraging studying, gave weapons against himself. I have heard an English gentleman say that he had seen a letter from Seigneur Polus, or Seigneur de La Pole [Reginald Pole (1500-58), cardinal and archbishop of Canterbury], who has since been made a Cardinal, to that Pope; in which, even as he congratulated him because he was extending the progress of science in Europe, he warned him that it was dangerous to make men too knowledgeable.

The Foundation of Empire is Art & Science Remove them or Degrade them & the Empire is No More—Empire follows Art & Not Vice Versa as Englishmen supposeBlake is referring to Essay sur l’histoire générale, et sur les moeurs et l’esprit des nations, depuis Charlemagne jusqu’à nos jours.78↤ 78. The work was translated as An Essay on Universal History, the Manners, and Spirit of Nations, from the Reign of Charlemaign to the Age of Lewis XIV (London: J. Nourse, 1759). There is no evidence of Blake’s owning this work.79↤ 79. Bentley includes no reference to the work in BB or Blake Books Supplement. Is it possible that he borrowed it from the library of his Parisian landlord? Essay sur l’histoire générale is not written in the most straightforward French. Blake therefore may have been grateful for the assistance of native French speakers, as Mark and Eleanor Martin presumably were, in understanding this passage.80↤ 80. There are parallels here with Blake’s apparent problems with Italian in Alessandro Vellutello’s sixteenth-century edition of Dante during the creation of his illustrations to The Divine Comedy, as discussed in Paley 111-12. The Martins may have also assisted Blake’s “learn[ing] French, sufficient to read it, in a few weeks.”81↤ 81. Living with two native speakers would certainly have facilitated his progress. Blake’s knowledge of French may lie behind Henry Crabb Robinson’s conversation with him on 18 Feb. 1826 (approximately five years after he had parted company with the Martins) concerning his frequent “intercourse with Voltaire”: “I asked in what langue. Voltaire spoke[;] [Blake] gave an ingenious answer—[“]To my Sensations it was English—It was like the touch of a musical key—He touched it probably French, but to my ear it became English[”]”[e] (BR(2) 434). Blake may also have learned some French while a neighbor of Hayley’s at Felpham, 1800-03.

On peut dire que la76 Pape Léon Xme en encourageant les Seigneur Anglais qu’il avait vu une Lettre du Seigneur Polus, ou de La Pole, depuis Cardinal, à ce Pape; dans laquelle, en le félicitant sur ce qu’il etendait le progrès de Science en Europe, il l’avertissait qu’il était dangereux de rendre les hommes trop Savans—

VOLTAIRE Moeurs de[s] Nation[s], Tome 4

O Englishmen! why are you still of this foolish Cardinals opinion?77

The findings discussed in this paper suggest a far more differentiated picture of life at South Molton Street over the almost two decades of William and Catherine Blake’s residence than has been previously realized. In earlier discussions of the inhabitants of South Molton Street, Mark Martin, “Mrs Enoch” and “a Frenchwoman,” though said to have been fellow lodgers of the Blakes, were little more than unrelated names. We can now begin to identify these fellow inhabitants, their relationship to one another, and the years they shared no. 17 with the Blakes. We can better imagine the relationships between William and Catherine and a number of their neighbors and fellow inhabitants—those who peopled their domestic universe. I hope that I have suggested how these discoveries enhance our knowledge of the Blakes during the first two decades of the nineteenth century, a period for which records relating to them are virtually nonexistent.

begin page 95 | ↑ back to topWorks Cited

Ackroyd, Peter. Blake. London: Sinclair-Stevenson, 1995.

Bentley, G. E., Jr. Blake Books. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1977.

—.[e] Blake Books Supplement. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995.

—.[e] Blake Records. 2nd ed. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004.

—.[e] The Stranger from Paradise: A Biography of William Blake. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001.

—,[e] ed. William Blake’s Writings. 2 vols. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1978.

Campbell, R. The London Tradesman, Being a Compendious View of All the Trades, Professions, Arts, Both Liberal and Mechanic, Now Practised in the Cities of London and Westminster. London: T. Gardner, 1747.

Chichester, H. M. “Leith, Sir James (1763-1816).” Rev. Roger T. Stearn. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. <http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/16409>.

Erdman, David V., ed., with commentary by Harold Bloom. The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake. Newly rev. ed. New York: Anchor-Random House, 1988.

Essick, Robert N. William Blake’s Commercial Book Illustrations: A Catalogue and Study of the Plates Engraved by Blake after Designs by Other Artists. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1991.

Falconar, Maria, and Harriet Falconar. Poems. London: J. Johnson, 1788.

Fiske, Tina. “Martin, William (b. 1753, d. in or after 1836).” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. <http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/18217>.

George, M. Dorothy. London Life in the Eighteenth Century. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1966.

Gilchrist, Alexander. Life of William Blake. Ed. Ruthven Todd. Everyman’s Library, no. 971. London: J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd.; New York: E. P. Dutton & Co. Inc., 1945.

Irwin, Margaret. South Molton Street Then As Now, the Favoured Resort of Modish Mayfair. London: G. A. Male & Son, 1927.

Keane, John. Tom Paine: A Political Life. London: Bloomsbury, 1995.

King, James. William Blake: His Life. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1991.

Lindsay, Jack. William Blake: His Life and Work. London: Constable, 1978.

Louth, Andrew. “Taylor, Thomas (1758-1835).” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. <http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/27086>.

McCarthy, William, and Elizabeth Kraft, eds. Anna Laetitia Barbauld: Selected Poetry and Prose. Ormskirk: Broadview Press, 2002.

Miner, Paul. “William Blake’s London Residences.” Bulletin of the New York Public Library 62.11 (Nov. 1958): 535-50.

Paley, Morton D. The Traveller in the Evening: The Last Works of William Blake. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Porter, Roy. London: A Social History. London: Penguin, 2000.

Ribeiro, Aileen. The Art of Dress: Fashion in England and France 1750 to 1820. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995.

Rogers, Pat. “Johnson, Samuel (1709-1784).” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. <http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/14918>.

Schwarz, L. D. “Social Class and Social Geography: The Middle Classes in London at the End of the Eighteenth Century.” The Eighteenth-Century Town: A Reader in English Urban History, 1688-1820. Ed. Peter Borsay. London: Longman, 1990. 315-37.

Steele, Valerie. The Corset: A Cultural History. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001.

Todd, Ruthven. William Blake: The Artist. London: Studio Vista Ltd., 1971.

Townend, Peter, ed. Burke’s Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Peerage, Baronetage and Knightage. 104th ed. London: Burke’s Peerage, 1967.

Wark, Robert R., ed. Sir Joshua Reynolds: Discourses on Art. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1975.

Waugh, Norah. Corsets and Crinolines. London: B. T. Batsford Ltd., 1954.

Whitehead, Angus. “New Discoveries Concerning William and Catherine Blake in Nineteenth Century London: Residences, Fellow Inhabitants, Neighbours, Friends and Milieux, 1803-1878.” PhD diss. 2 vols. University of York, 2006.

—.[e] “New Information Concerning Mrs Enoch, William and Catherine Blake’s “fellow inhabitant” at 17 South Molton Street.” Notes and Queries 250 (ns 52).4 (Dec. 2005): 460-63.

![46)

Rents Poor and Highways Watch Pav[ing] Cleans[ing] & Lighting Total

Robt. Huttersly . 28 3._.8 _.7._ _.14._ 4.1.8

IIII Wm. Spicer . . . . 28 3._.8 _.7._ _.14._ 4.1.8

IIII Wm. Small . . . . 28 3._.8 _.7._ _.14._ 4.1.8

IIII W: A: Scripps . . 28 3._.8 _.7._ _.14._ 4.1.8

IIII Edwd. Parish . . . 28 3._.8 _.7._ _.14._ 4.1.8

IIII Maria Radcliffe . 28 3._.8 _.7._ _.14._ 4.1.8

IIII Richd. May . . . . 40 4.6.8 _.10._ 1._._ 5.16.8

IIII Edmd. Treherne . 40 4.6.8 _.10._ 1._._ 5.16.8

Wm. Rowe . . . . . 40 4.6.8 _.10._ 1._._ 5.16.8

IIII Bynon Wilkinson 40 4.6.8 _.10._ 1._._ 5.16.8

IIII John Wilson . . . . 40 4.6.8 _.10._ 1._._ 5.16.8

IIII Robt. Morgan . . 40 4.6.8 _.10._ 1._._ 5.16.8

IIII Archd. Newland . 40 4.6.8 _.10._ 1._._ 5.16.8

IIII Martin & Stockhurn 44 4.15.4 _.11._ 1.2._ 6.8.4

IIII Fras. Tucker . . . 44 4.15.4 _.11._ 1.2._ 6.8.4

IIII Jos: Ward . . . . . 44 4.15.4 _.11._ 1.2._ 6.8.4

IIII Grace Weightman 40 4.6.8 _.10._ 1._._ 5.16.8

IIII Eliz: Parvin . . . . 44 4.15.4 _.11._ 1.2._ 6.8.4

IIII James Lay . . . . 44 4.15.4 _.11._ 1.2._ 6.8.4

IIII Benj: Bayfield . 44 4.15.4 _.11._ 1.2._ 6.8.4

81.9.4 9.8._ 18.16._ 109.13.4](img/illustrations/ratebook.43.3.bqscan.png)