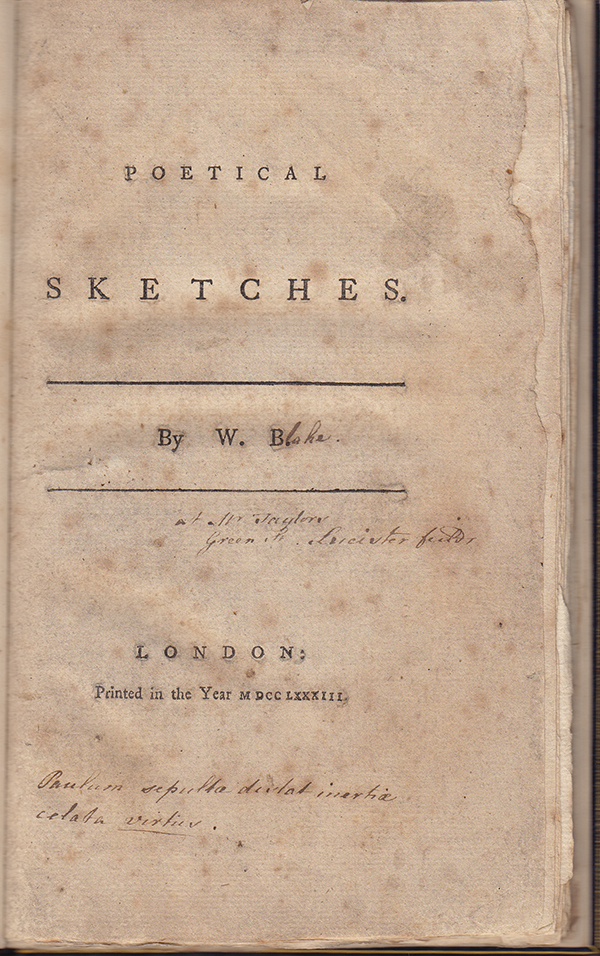

4. Poetical Sketches, title page, leaf 21.8 x 12.7 cm. with a ragged fore-edge and other evidence of flaws in the paper upper right. Essick collection, acquired at BHL, 22 March, #24. With the following pen and brown ink inscriptions: “lake” added following Blake’s initials printed on the title page to spell out his last name, “at Mr Taylors / Green St. Leicester fields” below the ruled line following “By W. B.,” and “Paulum sepulta distat inertiæ / celata virtus” in the lower margin. The dot of the “i” is so far displaced to the right in “Leicester” and “fields” that they appear to be misspellings, “Leicister” (with no dot over the first “i”) and “feilds.” Copy S of Poetical Sketches (Huntington Library) also has “lake” added, but in pencil.

The online auction cat. initially attributed “lake” and “at Mr Taylors …” to Blake, but this was met with less than universal assent. On the basis of digital images, G. E. Bentley, Jr., Alexander Gourlay, and Joseph Viscomi rejected the attribution by Bonhams. Ted Hofmann, senior specialist in English books at Quaritch, the venerable antiquarian bookshop, inspected the original. He did not believe that “lake” was written by Blake and found that “the very round ‘k’ seems quite impossible” (e-mail, 9 March 2011). When informed of these views, Bonhams added the following “Lot Notice” to its online cat. on 11 March: “The consensus of several scholarly oppinions [sic] is that the inscriptions on the title are not in the hand of William Blake.”

Cataloguers at Bonhams may have been led to their attribution by similarities between the “at Mr Taylors …” inscription and Blake’s hand in the manuscript of An Island in the Moon, generally dated to c. 1784-85. The stroking—that is, the sequence of directions in which the pen was moved to write the letters—is the same. The enlarged form of a lowercase “g,” used as a capital in “Green,” is the same in its upper elements as we see in the Island manuscript, including “Gimblet” and “Gass” on the first leaf (see the William Blake Archive <http://www.blakearchive.org.libproxy.lib.unc.edu>, object 1, lines 11 and 19). Gourlay, however, finds that the loop to the left of the descender of the “G” on the title page is a significant difference from examples in the Island manuscript, all of which show that Blake lifted his pen when drawing it back from the termination of the descender (e-mail, 8 March 2011). The paucity of looping verticals in examples of Blake’s handwriting, both formal and informal, is also crucial for Viscomi.

The Bonhams cat. claims that the Latin was inscribed by a hand different from the one that wrote the other inscriptions on the title page. Gourlay, Viscomi, and I believe that all 3 inscriptions are by the same hand, possibly writing at different times (e-mails, 12 May 2011). The ink color is the same, although “lake” may have been written with a wider nib. The auction cat. points out that the Latin is a quotation from “Horace’s Odes.” The passage appears in book 4, ode 9, lines 29-30, which can be roughly translated as “when courage lies hidden, it is little better than shame hushed up in the grave.” In lines just before those quoted, Horace states that brave men remain unknown unless their deeds are sung by poets. The relevance of the quotation to Blake and his poetry may be multiple. Several of the Poetical Sketches, including “A War Song to Englishmen” and “Samson” (E 440, 443-45), praise brave men. At least until the publication of Alexander Gilchrist’s biography in 1863, Blake could be characterized as a “hidden” artist and poet, brave in the realms of imagination.

Blake and his wife, Catherine, lived at 23 Green Street (now called Irving Street), Leicester Fields, from Aug. 1782 until they moved to 27 Broad Street late in 1784. Thus, the inscription on the title page records Blake’s residence when Poetical Sketches was printed. The Blakes evidently rented their lodging from Thomas Taylor (not the Platonist); he paid the rates on the property for these years (see BR[2] 740-41). The auction cat. claims that this copy was “clearly given by Blake” and that the inscribed address “gives dating to the presentation.” The inscription, “at Mr Taylors …,” indicates Blake’s location, not a presentation or gift to Taylor or anyone else. Paul Miner discovered that the aptly named Taylor was a tailor, as reported in [David V. Erdman], “Blake’s Landlord,” Bulletin of the New York Public Library 63 (Feb. 1959): 61. Perhaps Taylor had a shop on the ground floor with a sign that included his name. If so, then “at Mr Taylors …” would be a convenient way of locating a tenant renting rooms in the same building. William Hayley used this means of providing his wife with his London address in a letter of 16 April 1789, stating that she “will easily find the House [where he was residing] by the name Basire on the door” (BR[2] 740).

Blake’s Green Street address is recorded in the Royal Academy exhibition cat. of 1784 (BR[2] 850n21), but the name of his landlord was not discovered and published until 1958—see Miner, “William Blake’s London Residences,” Bulletin of the New York Public Library 62 (Nov. 1958): 539-40. Bentley, Gourlay, Viscomi, Windle, and I believe that the handwriting on the title page is certainly earlier than the mid-20th century. Indeed, the similarities between Blake’s hand and the title-page inscriptions suggest that the writer of the latter also learned penmanship in the 18th century. It seems probable that the inscriber of “at Mr Taylors …” had personal knowledge of Blake’s whereabouts or learned it from someone who knew Blake between the time the book was printed in 1783 and late 1784. The address would serve little purpose if not written during that same period, for only then would the information be of any use to the writer or others who might wish to know where to find the book’s author. If Blake acted as a distributor of his book, this would also be the address where copies of Poetical Sketches could be obtained. In his 1828 biography of Blake, John Thomas Smith states that “the whole copy” (apparently meaning the entire print run) of Poetical Sketches “was given to Blake to sell to friends, or publish, as he might think proper” (BR[2] 606).

Who among Blake’s circle of acquaintances and patrons might be a likely candidate for the author of the title-page inscriptions? Bentley has suggested, in a letter to me of 19 May 2011, that the first owner of this copy was the antiquarian, collector, and geologist John Hawkins (1761-1841; see the biography by H. S. Torrens in the ODNB). In a letter of 18 June 1783 to his wife Nancy, John Flaxman states that “Mr. Hawkins paid me a visit & at my desire has employed Blake to make him a capital drawing …” (BR[2] 28). In a letter to Hayley datable to 26 April of the next year, Flaxman indicates that Hawkins had commissioned “several drawings” from Blake and that Hawkins “is so convinced of his [Blake’s] uncommon talents that he is now endeavouring to raise a subscription to send him to finish [his] studies in Rome ….” Nothing came of this scheme, perhaps in part because, as Flaxman reports in this same letter, “Mr. Hawkins is going out of England” before “the 10th of May,” 1784 (BR[2] 31). This epistolary evidence indicates that Hawkins knew Blake (or at least knew his work) between June 1783 and May 1784, may have visited him “at Mr Taylors” or could have learned Blake’s address from Flaxman, and had a serious interest in acquiring Blake’s designs.

Comparisons between the title-page inscriptions and examples of Hawkins’s handwriting confirm Bentley’s insight. Hawkins’s hand is much like Blake’s in its stroking, but is rounder and loopier—the very characteristics that distinguish the inscriptions from Blake’s own hand. Gourlay has nicely summarized some of the more telling similarities between Hawkins’s writing and the inscriptions: “the G is a good match, the habit of starting looped ascenders about a third of the way up the height, the looped uncial d, the variants of e, the tiny hairlines connecting apparently discrete letters all look right to me” (e-mail, 26 May 2011). Every letter in the title-page inscriptions has good matches in Hawkins’s letters of 29 May 1814 and 23 Aug. 1816 to Samuel Lysons, including combinations of letters such as “Mr” (second letter a superscript) and “ke.” Hawkins’s education at Helston School, Winchester College (1775-77), and Trinity College, Cambridge (1778-82), would have provided sufficient instruction in Latin literature for him to have encountered the lines from Horace quoted on the title page.

Hawkins probably acquired this copy of Poetical Sketches sometime between its printing in 1783 and early May 1784 and inscribed the title page shortly after it came into his possession. It may have been a gift from Blake to this significant patron. The book may have passed to Hawkins’s elder son, John Heywood Hawkins (1802-77), who was bequeathed his father’s residence at Bignor Park, Sussex, or (less probably) to the younger son, Christopher Hawkins (1820-1903), who inherited his uncle’s Cornish properties, including Trewithen House and its library. Either line of descent probably led—either directly or through a subsequent generation—to the dealer, also residing in the south of England, named as the book’s former owner in the auction cat.: “Descendent [sic] of Frederick R. Jones, of ‘Eastbury’, Thames Ditton, Surrey, bookseller and antiques dealer, later of Adwell House, Torre, near Torquay.” Bonhams has no further ownership information. Hawkins’s “very fine mineral collection” was dispersed at “public auctions in 1905” (ODNB); perhaps Poetical Sketches left his library at about the same time. Bentley tells me (letter of 18 Aug. 2011) that there are no works by Blake in the auction of books from Hawkins’s Bignor Park library at Hodgson’s rooms, London, 16-17 Dec. 1926.

The comments here on Hawkins’s handwriting are based on the 2 letters cited above (West Sussex Record Office, Chichester, Add MS 7542 folios 22, 39) and samples reproduced in The Letters of John Hawkins and Samuel Lysons 1812-1830, ed. Francis W. Steer (Chichester: West Sussex County Council, 1966) 10, 17, 21, 23, 40, 44. A Victorian watercolor drawing of Hawkins’s extensive library at Bignor Park is reproduced in I am, my dear Sir … A Selection of Letters Written Mainly to and by John Hawkins, ed. Francis W. Steer (Chichester: n.p. [privately printed?], 1959), facing 33.