Blake’s Priestly Blessing: God Blesses Job

Abraham Samuel Shiff (abe.sam.shiff@gmail.com) studies at the Graduate Center, City University of New York, in the Master of Liberal Arts Program. He has also published on Shakespeare.

Blake portrays the Orthodox Jewish ritual for the priestly blessing in plate 17 of Illustrations of the Book of Job. This essay explains the ritual, analyzes Blake’s iconography, and argues why he resorts to this Jewish practice.

1. Zeitgeist

A history describing religion and culture in the England of 1815 observes that the period was “remarkable for its intense [Christian] religious life.”Halévy 1: 387. The study of Hebrew and Greek was encouraged to promote the reading of the Old and New Testaments in their original languages. A man of his time, Blake studied Hebrew and incorporated it into his art.See Shiff.

Not appreciated today—and crucial to my argument—is that the Protestant theologians also encouraged the study of Jewish religious rituals to understand how the ancient Israelites implemented biblical commandments. In the introduction to a book explaining Judaism to Christians, the Methodist theologian and scholar Adam Clarke (c. 1762–1832) urged: I have now reason to hope that every serious Christian, of whatever denomination, will find this Volume a faithful and pleasant guide to a thorough understanding of all the customs and manners, civil and religious, of that people to whom God originally entrusted the Sacred Oracles. Without a proper knowledge of these it is impossible to see the reasonableness and excellency of that worship, and of those ceremonies, which God Himself originally established among the Israelites ….Clarke vi. The “Volume” that Clarke refers to is a French book on the Jewish religion (based on Johannes Buxtorf’s Juden Schul) by Abbé Claude Fleury (1640–1723, a member of the French Academy), first translated into English in 1750. Clarke brought out three subsequent editions, with the fourth edition of 1820 enhanced and expanded. From Cromwell’s era there was a continuous immigration of religiously observant Jews to England. Succeeding generations separated from the Orthodox Jewish tradition into which they were born and educated, and assimilated into the predominant society—some converting to Christianity, the ultimate assimilation.In 1943 Abraham Cohen, an English rabbi and scholar, posed the question, what did Englishmen know about Jews and Judaism two or three centuries ago? From systematically assembled extracts from diaries, letters, and books of travel up to the Victorian era, he demonstrates the interest in Hebrew and Jewish practice and the study of Jewish religious literature by the clergy in Oxford and Cambridge, even before Cromwell’s time, and the constant curiosity about Jewish practice wherever Englishmen encountered Jews in foreign lands. He also gives examples of English Jews assimilating and converting: “The majority of the Jewish families which had settled in England under Cromwell, and prospered, disappeared from the [Jewish] community within a century …” (Cohen, An Anglo-Jewish Scrapbook 221). In cosmopolitan London, Blake had ready access to knowledge about Jewish religious rituals from assimilated or converted Jews and from fellow Protestants who studied Judaism to understand the roots of Christianity and to proselytize.See Ruderman and also Spector, especially her “Introduction: The Politics of Religion,” 1-13, and Schuchard’s “William Blake and the Jewish Swedenborgians.”

2. Ritual

To make the iconography of the priestly blessing in plate 17 understandable, I begin by explaining the ritual. The priestly duty to bless the children of Israel is a biblical command.Numbers 6.22-27: “22. And the Lord spoke unto Moses, saying: 23. ‘Speak unto Aaron and unto his sons, saying: On this wise ye shall bless the children of Israel; ye shall say unto them: 24. The Lord bless thee, and keep thee; 25. The Lord make His face to shine upon thee, and be gracious unto thee; 26. The Lord lift up His countenance upon thee, and give thee peace. 27. So shall they put My name upon the children of Israel, and I will bless them’” (Cohen, The Soncino Chumash 825-26). In this ritual, the blessing is from God through the agency of priests. The Hebrew word for priest is kohen (כהן). Aaron, the brother of Moses, was the first Jewish kohen,In the Orthodox tradition, a Jewish male attains the title of rabbi after completing theological studies. A priest may study to become a rabbi. In contrast, the title of priest is a birthright, automatically conferred upon a male whose father is a priest. A rabbi who is not of patrilineal descent from Aaron may not perform the priestly blessing or any other role a priest has in the religious life of an Orthodox Jewish community. A rabbi who happens to be a priest is obligated to observe the priestly duties. and the blessing mandated of him and his male descendants is a tradition that continues uninterrupted to this day by men who are priests by patrilineal descent.Patrilineal genealogy is embedded in the convention for naming children. Names in Hebrew for ritual purposes follow the biblical formulation. First is the individual’s given name(s), then the relationship to the father, followed by the father’s given name(s), e.g., B the son of A, or C the daughter of A. The honorific title Ha-Kohen (the priest) is appended to the father’s name if he is a descendant of Aaron. The father of Moses and Aaron was Amram, who was not a priest. Amram’s two sons were Moses son of Amram and Aaron son of Amram. After Aaron was appointed priest, his son was Eleazar son of Aaron the Priest. In turn, Eleazar’s son was Phinehas son of Eleazar the Priest. This convention maintains the tradition of priestly patrilineal genealogy. In the Orthodox Jewish tradition, the rite is performed only during certain prayer services to a congregation convened in a quorum.In the Orthodox tradition, the minimum requirement for a quorum is ten males who are thirteen or greater. The blessing is given if the quorum contains one priest at least of age thirteen. At the appropriate point in the service, the priests gather in a group before the assembly and in unison chant words unchanged from biblical times.Among the oldest biblical writings uncovered in Israel by archaeologists are amulets with the priestly blessing. For details, see Barkay et al., “The Challenges of Ketef Hinnom” and “The Amulets from Ketef Hinnom.” During the blessing, priests cover their heads and outstretched arms and hands with the talis (prayer shawl).The Hebrew word for prayer shawl is four letters (טלית) pronounced in two syllables. In Israel, where the Sephardic dialect predominates, it is pronounced “tah-lit,” while in the Ashkenazic dialect, whose origin is in eastern Europe and which was spoken by Jews in Blake’s London (and in which the author is educated), the pronunciation is “tah-lis.” Today the transliteration is usually spelled with a single “l” as talis or talit. The Encyclopaedia Judaica uses tallit:

Tallit, prayer shawl. Originally the word meant “gown” or “cloak.” This was a rectangular mantle that looked like a blanket and was worn by men in ancient times. At the four corners … tassels were attached in fulfillment of the biblical commandment … (Num. 15:38-41). … After the exile of the Jews [after the Romans destroyed the Second Temple] … and their dispersion, they came to adopt the fashions of their gentile neighbors …. The tallit was discarded as a daily habit and it became a religious garment for prayer; hence its later meaning of prayer shawl. The tallit is usually white and made either of wool, cotton, or silk …. Strictly observant Jews prefer [the tallit to be] made of coarse half-bleached lamb’s wool. The congregation stands and faces the priests, but does not gaze directly at their hands. The Bible does not detail the technical methodology for performing the blessing. Maimonides (1135–1204), in the Mishneh Torah, his code of Jewish practice, describes the procedure: When the leader of the congregation [leader of the prayers] reaches the blessing … all the priests in the synagogue leave their places, proceed forward, and ascend the duchan [the platform at the front of the synagogue on which is the heichel (ark containing the torah scrolls)]. They stand there, facing the heichel, with their backs to the congregation …. [Then] they turn their faces to the people [turn around to face the congregation], spread out their fingers, lift up their hands shoulder high, and begin reciting ….Maimonides 2: 190-92. Maimonides wrote the Mishneh Torah in classical Hebrew. He is known as the RAMBAM (pronounced in both Hebrew and English as two syllables, “Rahm-Bahm”), which is the pronunciation of the four-letter acronym (RMBM: רמבם) of his Hebrew name: Rabbi Moses ben [son of] Maimon. “Maimonides” is the Latinized version of “the son of Maimon.” His works translated into Latin were available to Christian theologians who were not Hebraists. After Maimonides there were other codes of Jewish law by rabbis of different communities and traditions, none of which needs to be entered into for the purposes of this paper. The practice for extending arms, hands, and fingers has several variations, with each priest using the tradition taught to him by his father.Gold explains that “there are more than a dozen customs on how the Kohanim [priests] hold their hands. All are equally valid …,” but illustrates only two (41). Rubenstein shows five positions (23-26). Six are in Katz (72-75), who advises that his “set of illustrations lists some of the hand and finger positions in use today.” In Berg’s unpublished thesis three hand positions are described, but not illustrated (74-75). Because of duplication, these works portray only six of the multiple traditional variations. The hands of the priests never touch the persons being blessed—there is no laying on of hands.Ritual handwashing is required before priests may give the blessing. Touching any person before completing the blessing renders a priest ritually impure and unfit to make the benediction, and rewashing is required. Priests are a clan of the tribe of Levy. In the days of the Temple, the priests officiated, performing the sacrifices and blessings. The patrilineal male descendants of Levy who were not of the priestly clan provided support services, including the purifying ablutions of the priests, and they are identified by the title Levite. The children of Levites are named B the son of A, the Levite, or C the daughter of A, the Levite. Today, in the Orthodox tradition, the obligation of washing the hands of priests preparatory to the benediction continues for male Levites.

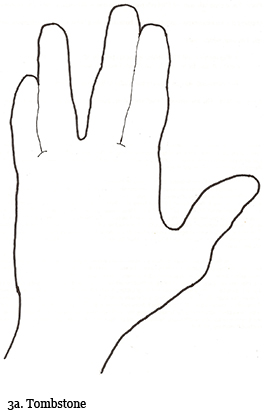

A representation of one of the more common finger configurations is often engraved on the tombstones of priests. Raised hands show fingers extended (see illus. 2).Hands held for blessing is the traditional gravestone emblem for the priest; for the Levite it is a water pitcher.

Line 1: A two-letter abbreviation for the phrase “here is interred.”

Line 2: The deceased’s two given names, Jacob Chaim.

Line 3: A two-letter abbreviation for the phrase “the son of Reb” (Reb is a general honorific title), the deceased’s father’s single given name, Mordechai, and the title “the Priest.”

The balance of the inscription (not shown) has the dates of birth and death, the given and family names in English, and a message appropriate to the memory of the deceased.

As shown by the tombstone, the symmetrically arranged hands are in contact at two points: thumb-tip to thumb-tip and index-finger tip to index-finger tip. Of the fingers on each hand, some touch along their full lengths, while others are separated: the thumb is apart from the index finger; the index and middle fingers touch; the middle finger is apart from the ring finger; and the ring and little fingers touch. The religious significance is not in the touching, but in the gaps established by the symmetrical separations. The gaps represent the lattice fence in the Song of Songs,Song of Songs 2.9: “9. … Behold, he standeth behind our wall, He looketh in through the windows, He peereth through the lattice” (Cohen, The Five Megilloth). here metaphorically formed by the fingers at the ends of a priest’s outstretched arms, interposed between God and God’s agent—the priest—and the people receiving the blessing.

To summarize, the five characteristics of the ritual are:For details of the ritual, its history in Orthodox Jewish practice, and the prayer services during which the priestly blessing is given, see Gold. After the Enlightenment, Jews in England (and elsewhere) separated from the Orthodox tradition and adopted reformed religious practices, including changes to the ritual of the priestly blessing. The Orthodox practice is pertinent to this paper because the English Reform liturgy is essentially post-Blake.

A: Both arms are extended in parallel.

B: Both arms are held horizontal.

C: Fingers of both hands are held in a symmetrical pattern to create gaps.

D: Palms are toward the recipients of the blessing.

E: Recipients of the blessing do not gaze at the priest’s hands.

God blesses Job in plate 17. Every one of the five characteristics of the priestly blessing is present.

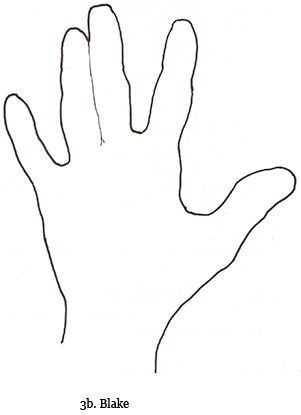

Before I analyze the iconography, two points should be remembered. First, how easily the ritual is described, especially when accompanied by a demonstration of the hand position (see illus. 3). This is all the information Blake would have needed to compose the blessing scene in plate 17. Second, and more importantly, the technique is not described in the Bible. Blake could not have known of it from self-study of the plain text (the words in the Bible without exegetical commentary).

3. Iconography

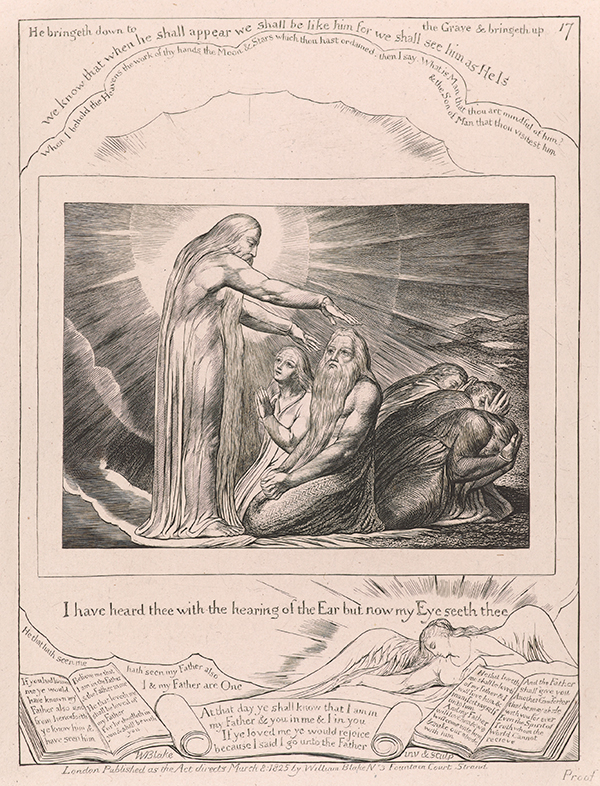

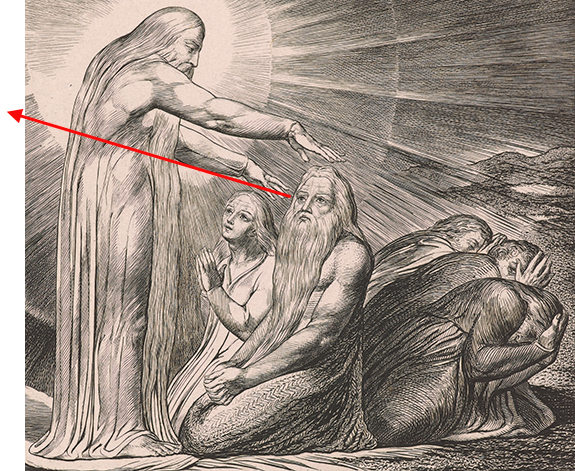

Plate 17 (illus. 1) depicts two sentences from the last chapter in Job. The plain text of Job 42.5 tells of Job’s gazing upon God.Blake engraved Job 42.5 beneath the image: “I have heard thee with the hearing of the Ear but now my Eye seeth thee.” The tableau shows Job kneeling before Blake’s typical depiction of God—a figure with a pensive expression and flowing hair and beard who radiates glory. Seven sentences further on God blesses Job (42.12).Job 42.12 is engraved beneath the image on plate 21: “So the Lord blessed the latter end of Job more than the beginning.” Job, restored to prosperity, is surrounded by his new family—the consequence of God’s blessing. Blake conflates the two into a single composition to show God in the act of blessing. The five characteristics are present.

A: Both arms are extended in parallel.

B: Both arms are held horizontal.

The first two are obvious in plate 17 and require no analysis.

C: Fingers of both hands are held in a symmetrical pattern to create gaps.

What Blake engraved requires close examination by magnification. The configuration of the left hand is obvious, even when not enlarged. Perceivable only when magnified are the telltale details of the right hand. First, see illus. 3 for a diagrammatic comparison: the image from the tombstone is illus. 3a, while illus. 3b is what Blake portrays in plate 17.

Pierpont Morgan Library, New York. PML 30214. Gift of Philip Hofer, 1934.

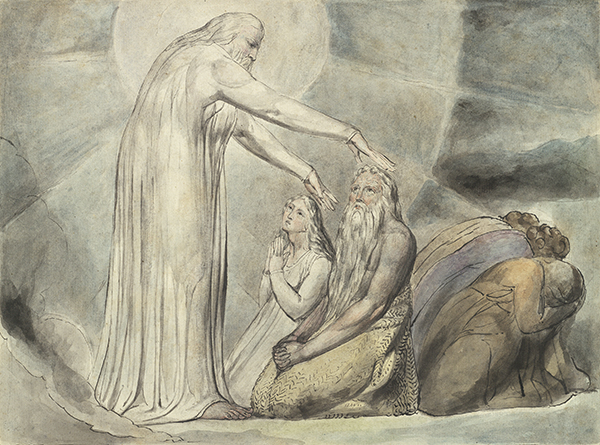

In contrast, the hands in the watercolors for Thomas Butts and John Linnell are not symmetrical (illus. 5-6). Absent in both drawings is the symmetry of finger gaps, because Blake drew the right hand to be seen on edge, and did not carefully detail that hand’s gaps (though the red arrow in illus. 6 indicates one gap). Whatever his reason for not showing the gaps in the drawings, Blake included this crucial feature in the engraving.

Photo: Allan Macintyre. © President and Fellows of Harvard College.

Two differences between plate 17 and the tombstone require comment. The first is that Blake shows the hands separated from one another. This is not a concern, as hands symmetrically positioned but not in contact is a traditional variation. The second difference is that Blake’s version of the finger gaps is not one of the six portrayed in the references I cited.See note 14. Two of the five positions in Rubenstein and two of the six in Katz show hands apart. In all instances, the configurations of hands and fingers are symmetrical. The simplest assumption to explain Blake’s configuration of finger gaps is that he never personally observed the priestly blessing given in a synagogue, and that his source taught him the positions shown in illus. 3b. Perhaps it is a variant tradition alluded to but not illustrated in the references, or it may be Blake’s understanding of a description he read somewhere.

Information about the ritual was readily available in books. A 1656 translation of Buxtorf’s Juden Schul gives this description: The Priest, putting on his Talles, which is a course hair cloth,For an explanation of a “talles” (talis) made from “course hair cloth,” see note 12. which was folded about his neck over his head, so as it may hide his eyes, blesses the people with the usuall benediction as was commanded Numb. 6. Which while he pronounces, the people put their hands before their faces, not daring to look upon his hands, because the spirit of God rests on them during the benediction, as ’tis written Cant. 2.9. Behold he standeth behind our wall, he looketh forth at the window, shewing himself through the lattesse. that is, God standeth behind the Priest, and looketh through the distances of his fingers.Ross 366. This translation is attributed to the clergyman and scholar Alexander Ross (1591–1654). Buxtorf (1564–1629) was the preeminent Protestant Hebraist of his generation, professor of Hebrew at Basel University, author and publisher of Hebrew lexicons and rabbinic literature, and the official censor of Hebrew publishing at Basel. He had extensive contact with Jews at the Frankfurt book fairs and with the Jewish proofreaders at the Basel press, and corresponded in Hebrew with Jewish booksellers throughout Europe. For a biography of Buxtorf and his son of the same name, an eminent Hebraist in his own right, and an introduction to Protestant Christian Hebraist scholarship, see Burnett. Buxtorf’s Juden Schul was published in nineteen editions, translated into Dutch, French, Latin, and English, and became the sourcebook for Christian theologians about Jewish religious practice. Additional detail is in another translation, from 1663: Then the Priest wrapping a great hair-cloth about his neck, and drawing it over his head, so far untill it come to the threshold of his eyes: he blesseth the people according to the ordinary forme prescribed by Moses, Numbers the 6, the 24, 25, 26, and 27 verses. When he pronounceth the blessing, he stretcheth out his hands towards the people: they covering their faces with their own; for it is lawful for no man to look upon the hands of the Priests: because the spirit of the Lord rests upon them, while he blesseth the Congregation. As it is written, He standeth behinde our wall looking forth at the windows, shewing himself through the grates, that is to say, God stands at the Priests back, and looks through the windows and grates, that is to say, through his hands being stretched out, and his fingers being spread abroad severed one from another.A. B. 235. Versions of Buxtorf were published three times in London between 1734 and 1748.Johann Andreas Eisenmenger’s Entdecktes Judentum was Englished by John Peter Stehelin and published in London in three known editions with Buxtorf as an accompanying volume: 1734 (copy in the New York Public Library); 1743 (Eighteenth Century Collections Online [ECCO] Part II); and 1748 (ECCO). For Buxtorf’s description of the priestly blessing, see 2: 340. The title page of the 1734 edition, vol. 1, states that the accompanying work is “Abridg’d from the Latin of Buxtorff.” However, none of the descriptions gives detailed information about how the hands and fingers are configured.

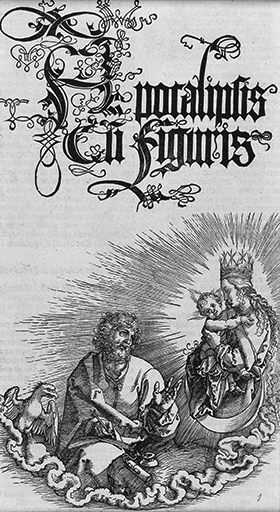

Perhaps Blake adopted what he believed to be a Christian religious equivalent. He favored Albrecht Dürer,“Blake was a print-seller for a time, and he had an extensive print collection of his own, started in his boyhood and sold in 1821, when his poverty was most severe. Nothing is known about what Blake sold or collected except that his taste ran to Dürer and to sixteenth-century Italian engravers, out of fashion at the time” (Johnson 154). whose Apocalypse woodcuts have examples of the hand position of illus. 3b (see illus. 7 and 8). If not from Dürer, then of course the model may have been from some other work. An exhaustive review of possible sources is beyond the scope of this paper.Warner does not describe the hand and finger positions in plate 17, and she makes no comment about Blake’s portraying the Jewish ritual of the priestly blessing. She does suggest the possible influence on Blake by John Bulwer. In 1644, Bulwer published a work describing the conventions of hand and arm configurations used to embellish vocal orations, with five charts of woodcuts depicting a subset of the many conventions discussed. Warner reproduces three of the charts on pp. 50, 51, and 56 of her work. The chart on p. 50 has twenty-four images, of which image Z, “Benedictione dimittit,” is Bulwer’s representation of the priestly blessing. In the section of his text entitled Chironomia, Bulwer explains image Z in five pages (59-63): “Canon XLIX. Both Hands modestly extended and erected unto the shoulder points, is a proper forme of publicke benediction, for the Hands of an Ecclesiasticall Oratour when hee would dismisse his Auditours.” He then expounds on the significance of the gesture, drawing on the Bible, Jewish tradition (as he understands it), Buxtorf’s Juden Schul, Roman Catholic tradition, and the gestures used by Protestant preachers that he personally observed. Although Bulwer describes the significance of the finger positions, his visual representation (image Z) fails to conform to the Jewish ritual, as the arms are vertical and the four fingers of each hand are not symmetrically separated. The other two-handed configurations in the chart that superficially resemble what Blake engraved in plate 17 are described by Bulwer as other than benedictions or the offering of blessings. Bulwer was not Blake’s authority for plate 17. Cleary’s 1974 edition of Bulwer begins with a scholarly introduction, modernizes Bulwer’s English, and translates his Latin quotations. In the notes, Cleary identifies and lists as fully as possible the source documents that are cryptic in Bulwer’s marginal notes and the sources for the Latin quotations, and he also defines obscure terms. He does not, however, comment on the images in the charts. Bulwer (1644) and Cleary’s edition of Bulwer (1974) could not have been of any assistance to Warner in recognizing what Blake did in plate 17.

Photo: René-Gabriel Ojéda. © RMN–Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY.

Photo: René-Gabriel Ojéda. © RMN–Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY.

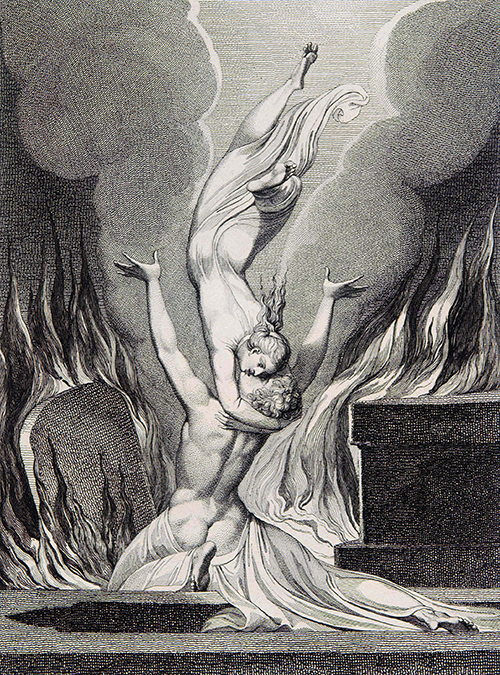

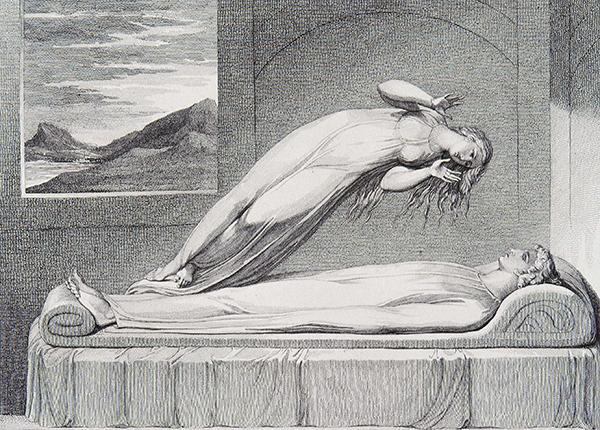

Immanentistic Emblem

Had Blake depicted in plate 17 the finger gaps portrayed in illus. 3a, this alone would make it certain that he emulates the Jewish priestly blessing. Had he depicted the configuration of illus. 3b in plate 17 and nowhere else, then it would unambiguously be associated with God’s delivering a blessing. Nowhere, however, do I observe his using the positions of illus. 3a. Instead, he uses those of illus. 3b in many compositions, most of which do not obviously show God in the act of blessing. Four such examples are in illus. 9-12. A survey of Butlin finds forty-two images with one or more instances of the positions of illus. 3b in a wide variety of settings and themes.Butlin pls. 57-58, 102-03, 122, 125, 151, 177, 185, 201, 223, 288, 305-06, 417-18, 497, 506, 508, 511, 522, 535, 557, 560, 570, 588-89, 647, 684, 686-88, 696, 700, 890, 892, 920, 962-63, 965, 1017, and 1095. Pl. 892, Christ Blessing (c. 1810), has the fingers of both hands configured as in illus. 3b, but without any of the other characteristics of the Jewish priestly blessing.

Joseph H. Wicksteed provides a solution in describing Blake as an “immanentalist.”“But for an immanentalist like Blake …” (Wicksteed 27). I suggest that Blake (who was steeped in the emblem tradition, as Mary Lynn Johnson explains)See Johnson. adopted the finger positions of illus. 3b as an emblem. Francis Quarles (1592–1644) defines the religious meaning of emblems in his Emblemes, which pairs parables expressed in words with their equivalents in woodcut images: TO THE READER. An Embleme is but a silent Parable. Let not the tender Eye checke, to see the allusion to our blessed Saviour figured, in these Types. In holy Scripture, He is sometimes called a Sower; sometimes, a Fisher; sometimes, a Physitian: And why not presented so, as well to the eye, as to the eare? Before the knowledge of letters, God was knowne by Hierogliphicks; And, indeed, what are the Heavens, the Earth, nay every Creature, but Hierogliphicks and Emblemes of His Glory?Quarles sig. A3. The hand with fingers configured as in illus. 3b is an immanentistic emblem that represents God’s ever-present blessing (see illus. 9-12). It is for this purpose, I suggest, that Blake used it in many compositions, including plate 17 where it is certain that God is blessing Job.

Purchased with the assistance of the fellows with the special support of Mrs. Landon K. Thorne and Mr. Paul Mellon.

Blake’s watercolor design shows the same hand and finger positions (see William Blake Archive, Drawings and Paintings, Water Color Drawings, Illustrations to Robert Blair’s “The Grave,” object 15).

Image courtesy of the William Blake Archive <http://www.blakearchive.org>.

Blake’s watercolor design shows the same hand and finger positions (see William Blake Archive, Drawings and Paintings, Water Color Drawings, Illustrations to Robert Blair’s “The Grave,” object 9).

Image courtesy of the William Blake Archive <http://www.blakearchive.org>.

Theme in Variation

Plate 17 is not alone in showing outstretched arms held parallel, as Blake uses this configuration in three other plates in Illustrations of the Book of Job. Alexander Gilchrist perceives the repetition to be an artistic flaw;“Such defects as exist in these [Job] designs are of the kind usual with Blake …. The lifted arms and pointing arms in plates 7 and 10 are pieces of mannerism to be regretted, the latter even seeming a reminiscence of Macbeth’s Witches by Fuseli …” (Gilchrist 1: 289). I suggest that it is a theme in variation.

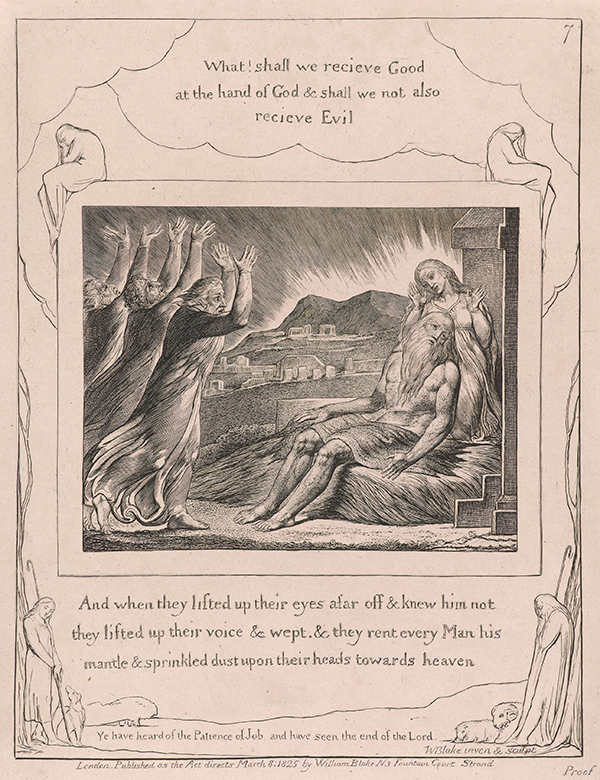

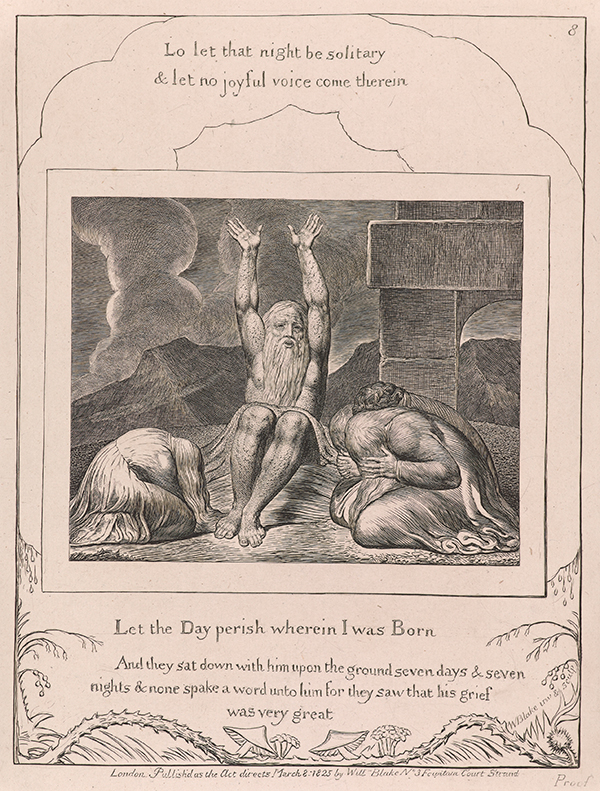

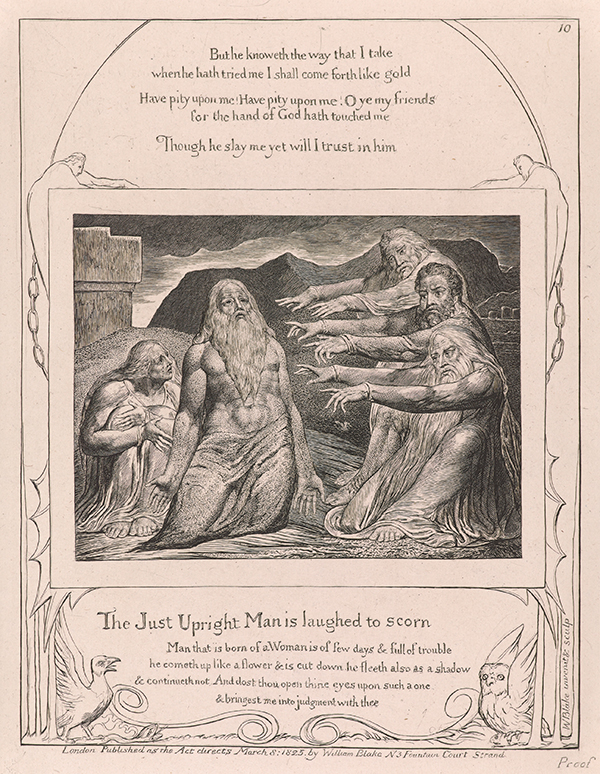

In plate 7 (illus. 13) Job’s friends raise parallel arms vertically with fingers splayed. This is not a blessing but a gesture of alarm and dismay.

PML 30214. Gift of Philip Hofer, 1934.

PML 30214. Gift of Philip Hofer, 1934.

PML 30214. Gift of Philip Hofer, 1934.

Only in plate 17 does Blake bring together arms, hands, and fingers properly configured for forming the metaphorical lattice fence necessary for the blessing ritual.

D: Palms are toward the recipients of the blessing.

In plate 17, God’s palms face toward Job—there is no laying on of hands.Blake depicts God’s hands above Job’s head. There is a custom (not a biblically ordained commandment) for parents to bless children at home on Friday evenings at the start of the Jewish Sabbath by the laying on of hands. The father places his hands on the head of the oldest child and invokes a blessing (not necessarily using the words of the priestly blessing), then repeats the process with each child in age order. In some families the mother does the same. This is not the priestly blessing, which is restricted to priests in a congregation convened in a quorum for prayer, and does not utilize the laying on of hands. The composition places God and Job in close proximity, so Blake could easily have put the hands of God on Job’s head, had he chosen to do so. See illus. 17 for an example of Blake’s depicting the laying on of hands. In contrast, the blessing in plate 17 is from a distance.

E: Recipients of the blessing do not gaze at the priest’s hands.

Throughout the Job plates, whenever Blake portrays God and humans in the same tableau, the humans do not look at God’s radiating glory.Plate 2 is composed of two separate tableaus, God in heaven and humans on earth. The humans are not in the presence of God’s glory. We see the same in plate 5. Plate 9 depicts a dream discussed by one of Job’s friends—God is not present, as he is recalled in the dream, which is shown in a “balloon” of clouds. In plate 13 Blake has Job’s wife and friends present when God appears (the friends hide their faces, but Job’s wife does not). The compositional separation is the whirlwind. Plate 14 shows two tableaus, humans beneath heaven, and God above. Two tableaus are depicted in plates 15 and 16 also. In plate 17 Job’s friends avert their faces (though one attempts to peek), but his wife does not. Plate 18 has the smoke from the burnt offering on the altar ascending without turbulence; this is proof of acceptance by God. The human figures kneel with eyes averted, except for Job, who looks upward toward the glorious radiance that Blake associates with God. Job does not look upon God, because God is not portrayed in the tableau. Finally, in plate 20, God is depicted on a decorative panel behind Job, with the humans in the panel bowed and not looking at God. God is not in the foreground with Job, and the daughters have no need to hide their faces. In the biblical plain text, God blesses Job, with no mention of the presence of Job’s wife or friends. With artistic liberty, Blake includes them in plate 17. Job’s friends avert their eyes (though one attempts to peek). This is consistent with the practice that a congregation does not look at the priest’s hands during the ritual—the hands form the representation of the lattice fence, with God’s presence on the far side. Job also does not look directly upon God (see illus. 18).

A comparison of the Butts and Linnell drawings confirms that Blake intended the plate to represent the synagogue ritual. Job avoids gazing at God in the Butts image (illus. 5), but looks directly at him in the Linnell (illus. 6). Why this difference? The Linnell is in conformance with the biblical plain text of Job 42.5 (see illus. 1): “I have heard thee with the hearing of the Ear but now my Eye seeth thee.” The Butts conforms to the synagogue ritual of avoiding gaze. Blake evaluates the two compositions. The quandary is that he cannot have it both ways and must choose one over the other for the engraving. He chooses to engrave the synagogue ritual.I offer no comments on the other differences: (1) In the Butts, God is erect, whereas he is stooped in the Linnell—the Linnell version is chosen for the engraving; (2) The three friends kneel forward toward God in the Butts, and away from him in the Linnell—again Blake chooses the Linnell version. Not pertinent to this analysis are the pencil sketch for the design and the New Zealand set (see Illustrations of the Book of Job by William Blake fascicles IV and V and, for the sketch, the William Blake Archive [Drawings and Paintings, Pencil Sketches, Sketchbook Containing Drawings for the Engraved Illustrations to the Book of Job, object 23]).

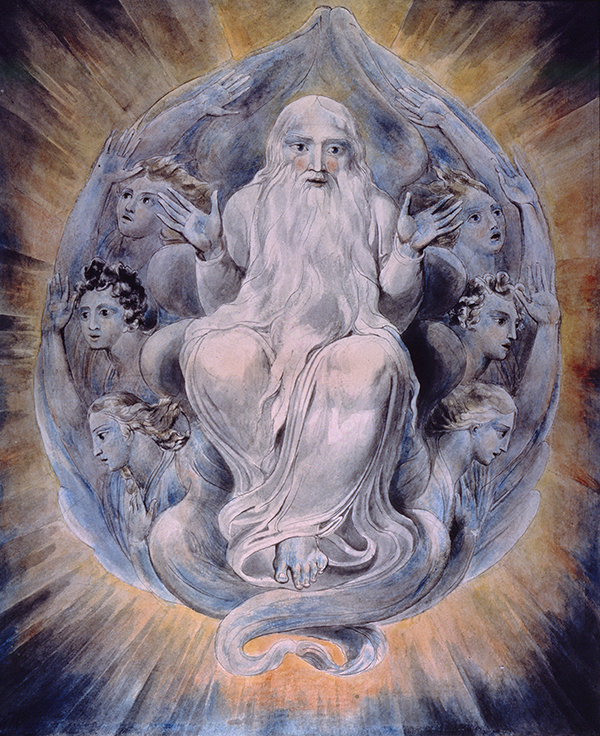

Avoiding gaze is a subtle feature in the watercolor God Blessing the Seventh Day (c. 1803–05) (illus. 19).Keynes dates the painting to “about 1803” (William Blake’s Illustrations to the Bible xii); Butlin (1: 336) suggests c. 1805.

Photo: Art Resource, NY.

This is Blake’s typical depiction of God—pensive expression, flowing hair and beard, radiating glory. Four of the ritual’s characteristics are obvious. Palms are toward the observer. The hands are symmetrically held at shoulder height, with fingers arranged as in illus. 3b. The arms are parallel, but not extended horizontally. I explain the arms folded at the elbows by assuming artistic liberty—Blake is avoiding the foreshortening effect that would occur if the arms were horizontal and fully outstretched, jutting forward at shoulder height into the observer’s space.

The last characteristic, averting gaze, is present but deliberately not made obvious. W. Graham Robertson, an owner of this painting and an artist himself, offers this criticism: “The colour throughout is fine, and the design impressive, but the central Figure [God] cannot be considered successful.”Robertson 119. The editor quotes Robertson’s and Rossetti’s descriptions of God Blessing the Seventh Day. Rossetti described it as “very characteristic and fine”; Robertson, however, criticized Blake’s portrayal of God. Did Blake really err? The difficulty, I suggest, is not with Blake’s execution, but with Robertson’s comprehension. Because he lived in a later zeitgeist, Robertson more than likely lacked Blake’s knowledge of Jewish religious practice and was unable to recognize the subtle but critical feature of averted gaze in a painting whose theme is God in the act of blessing. The challenge of living in a different zeitgeist also applies to Wright (see note 37), who did perceive the averted gaze in plate 17 but could not decipher Blake’s intention. He does not explain what he finds disturbing—I surmise it is the direction of God’s gaze. God should be looking directly at the seventh day he is blessing, as in plate 17 where he looks directly at Job. If the observer is standing in the position supposedly occupied by the seventh day, there should be eye-to-eye contact when the observer looks at God’s face. Instead, God appears focused elsewhere. Here Blake introduces the synagogue practice that those who are receiving the blessing do not look directly upon God, who is beyond the metaphorical lattice fence formed by the priest’s fingers. Blake has God focused on the seventh day, not on the observer. The painting is a depiction of God blessing the seventh day, just as the title indicates. It is the seventh day that should avert gaze, not the observer. Thus, there is no eye-to-eye contact.

Finally, observe the six angelic figures flanking God, with all wings (but two) folded and in which God nestles, as if seated on a throne of angel feathers. Each angel holds aloft one hand, palm side out, the fingers of which are in the position of illus. 3b, echoing the blessing theme. (Why six angels? Possibly the six days that precede the seventh day.)

In both God Blessing the Seventh Day and plate 17, Blake depicts the characteristics of the Orthodox Jewish synagogue ritual for the priestly blessing. The feature he chooses to make subtly obscure differs, however. In God Blessing the Seventh Day it is an averted gaze; in plate 17 the hidden feature is the finger gaps of the right hand. Blake deliberately introduces subtleties. Another example is in the watercolor Job’s Evil Dreams (Butts set), where three Hebrew words intended to represent a portion of the Ten Commandments are not a commandment at all, but a hidden message. “Blake precisely depicts the plain text of the Bible …. He then adds imagery not in the Bible …. Blake deliberately made the slogan appear to be a commandment—a visual illusion.”Shiff pars. 19-20. A future essay will argue why Blake does this.

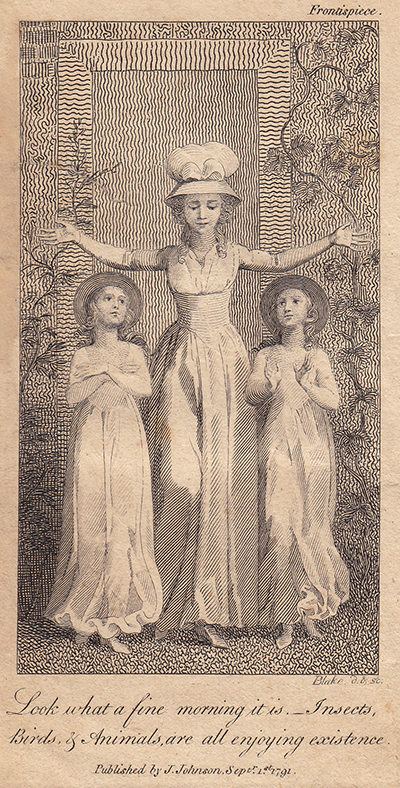

Unanswered is which came first, Blake’s knowledge of the priestly blessing whence he developed the emblematic symbol (illus. 3b), or his adoption of an existing Christian convention, later to be incorporated into the compositions where God blesses in plate 17 and God Blessing the Seventh Day. The dating is instructive. God Blessing the Seventh Day is c. 1803–05. “Look What a Fine Morning It Is” (illus. 10), clearly not the depiction of a priestly blessing and just the use of an immanentistic emblem,Arms are not parallel. Palms are not facing down. The figure is not a Jewish priest. The setting is not a synagogue with a quorum in attendance. The full title indicates that the hand gesture is Blake’s emblematic representation for God’s ever-present blessing: “Look what a fine morning it is._Insects, Birds, & Animals, are all enjoying existence.”

Not surveyed for this paper is the earliest occurrence in Blake’s work of the gesture as a stand-alone emblematic symbol, or its use by other artists. is 1791. By the end of his stay in Felpham (1800–03) or soon after, Blake knew and used all of the features characteristic of the Jewish priestly blessing.

4. Verisimilitude

Blake painted biblical scenes for his patron Butts, including Zacharias and the Angel (illus. 20).

Image © Metropolitan Museum of Art. Reproduction of any kind is prohibited without express written permission in advance from the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Verisimilitude, then, is the critical concept in understanding the iconography of the Bible series and Illustrations of the Book of Job. However, because there is no description in the Bible as to how God goes about giving a blessing, or the technique by which the priests are to perform the rite, Blake must rely on the synagogue practice of the Jews for a model.

The verisimilitude argument raises a problem that may not be ignored. In plate 17 God’s hands hover above either side of Job’s head. Clearly, the blessing is for Job alone, and this depiction is consistent with the Bible’s plain text. Contrary to the biblical story is the presence of Job’s wife, who is beside him as if also receiving the blessing, and who gazes directly at God. Why Blake gives her a prominence that is the antithesis of verisimilitude remains to be explored in a future essay.

Conclusion

Blake was a religious personality in a Christian zeitgeist that promoted and encouraged the study of the Israelite implementation of God’s revealed Law. In cosmopolitan London knowledge about Judaism was readily available. It should not be surprising that Blake relied upon the Orthodox Jewish synagogue ritual of the priestly blessing as his model for depicting how God blesses Job.

Graduate Center of the City University of New York

Professor Martin Elsky: I especially wish to express my appreciation for a courtesy that facilitated the writing of this paper. I enjoyed being his student and have benefited from his erudition.

To research Blake while studying at the Graduate Center is to have the advantage of access to the research collections of the Morgan Library and Museum and the New York Public Library. It is a pleasure to acknowledge staff at both institutions for their support:

Morgan Library and Museum

Anna Lou Ashby, retired Andrew W. Mellon curator: I am ever grateful to Dr. Ashby for introducing me to the study of Blake. Her encouragement is the reason why my papers on Blake have come to be.

Inge Dupont, retired head of reader services: She always brought yet another book to my attention that proved important for my research.

Reading Room: John Vincler, head of reader services (himself a Blake enthusiast); Maria Isabel Molestina Triviño, librarian; Sylvie Merian, librarian; and Sandy Kopperman, attendant.

Thaw Conservation Center: Frank Trujillo, associate book conservator, for micrographic imaging.

New York Public Library—Research Departments

Dorot Jewish Division: Roberta Saltzman, assistant chief librarian; and Amanda Seigel, librarian.

Manuscripts and Archives Division: Thomas Lannon, assistant curator; Tal Nadan, reference archivist; Susan Malsbury, manuscripts specialist; and Nasima Hasnat, assistant.

Pforzheimer Collection: Elizabeth Campbell Denlinger, curator.

Print Collection: Margaret Glover, librarian; Alvaro Lazo, specialist; and David Christie, specialist.

Rare Book Division: Jessica Pigza, assistant curator; Kyle Triplett, librarian; and Ted Teodoro, assistant.

Wertheim Study Room: Jay Barksdale, librarian, for granting me privileges to use this resource.

It is a personal pleasure to acknowledge the assistance of my friend Professor Ari Cohen, himself a kohen, for his review of the manuscript and for many valuable suggestions.

My special thanks are proffered to Sarah Jones, managing editor of Blake, whose meticulous editing and support in manifold ways brought the manuscript to a polished finish.

Lastly, any errors in this paper are solely the responsibility of the author.

Works Cited

B., A. The Jewish Synagogue, or an Historical Narration of the State of the Jewes, at This Day Dispersed over the Face of the Whole Earrh. In Which Their Religion, Education, Manners, Sects, Death and Burial Are Fully Delivered, and That out of Their Own Writers. Translated out of the Learned Buxtorfius, Professor of the Hebrew in Basil, and Diligently Compared with the Talmud, and Other Writers, out of Which It Had Its Original. London: Printed by T. Roycroft for H. R. and T. Young, 1663.

Baetjer, Katharine. British Paintings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1575–1875. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art; New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009.

Barkay, Gabriel, et al. “The Amulets from Ketef Hinnom: A New Edition and Evaluation.” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research no. 334 (May 2004): 41-71.

---. “The Challenges of Ketef Hinnom: Using Advanced Technologies to Reclaim the Earliest Biblical Texts and Their Context.” Near Eastern Archaeology 66.4 (Dec. 2003): 162-71.

Berg, Peter S. “The History, Function, and Ritualization of Birkat Kohanim.” Thesis. Hebrew Union College, 1998.

Blake, William. Illustrations of the Book of Job by William Blake: Being All the Water-Colour Designs Pencil Drawings and Engravings Reproduced in Facsimile. With an introduction by Laurence Binyon and Geoffrey Keynes. New York: Pierpont Morgan Library, 1935.

---. Illustrations of the Book of Job Invented and Engraved by William Blake 1825. London: Published as the Act directs March 8:1825 by William Blake No 3 Fountain Court Strand, [1826].

---. William Blake’s Illustrations to the Bible. A catalogue compiled by Geoffrey Keynes. Clairvaux [France]: Trianon Press for the William Blake Trust, 1957.

Bulwer, John. Chirologia: or the Natural Language of the Hand; and Chironomia: or the Art of Manual Rhetoric. Ed. James W. Cleary. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1974.

---. Chirologia: or the Naturall Language of the Hand. Composed of the Speaking Motions, and Discoursing Gestures Thereof. Whereunto Is Added Chironomia: or, the Art of Manuall Rhetoricke. Consisting of the Naturall Expressions, Digested by Art in the Hand as the Chiefest Instrument of Eloquence, by Historicall Manifesto’s, Exemplified out of the Authentique Registers of Common Life, and Civill Conversation. With Types, or Chyrograms: Along-Wish’d for Illustration of This Argument. London: Printed by Tho. Harper, and are to be sold by R. Whitaker, at his shop in Pauls Church-yard, 1644.

Burnett, Stephen G. From Christian Hebraism to Jewish Studies: Johannes Buxtorf (1564–1629) and Hebrew Learning in the Seventeenth Century. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1996.

Butlin, Martin. The Paintings and Drawings of William Blake. 2 vols. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981.

Clarke, Adam. The Manners of the Antient Israelites; Containing an Account of Their Peculiar Customs, Ceremonies, Laws, Polity, Religion, Sects, Arts and Trades …. The Fourth Edition, with Many Additions and Improvements. London: Printed for W. Baynes and Son, J. Butterworth and Son, and T. Blanshard, 1820.

Cohen, Abraham. An Anglo-Jewish Scrapbook 1600–1840: The Jew through English Eyes. London: M. L. Cailingold, 1943.

---, ed. The Five Megilloth: Hebrew Text and English Translation with Introductions and Commentary. 1946. 5th impression. London: Soncino Press, 1965.

---, ed. The Soncino Chumash: The Five Books of Moses with Haphtaroth: Hebrew Text and English Translation with an Exposition Based on the Classical Jewish Commentaries. 1947. 5th impression. London: Soncino Press, 1964.

Eisenmenger, Johann Andreas. Rabbinical Literature: or, the Traditions of the Jews, Contained in the Talmud and Other Mystical Writings. … With an Appendix, Comprizing Buxtorf’s Account of the Religious Customs and Ceremonies of That Nation …. By the Revd Mr. J. P. Stehelin, F.R.S. 1734 [under the title The Traditions of the Jews]. 2 vols. London: Sold by J. Robinson, 1748.

Gilchrist, Alexander. Life of William Blake, “Pictor Ignotus.” 2 vols. London: Macmillan, 1863.

Gold, Avie. Bircas Kohanim: The Priestly Blessings. Background, Translation, and Commentary Anthologized from Talmudic, Midrashic, and Rabbinic Sources. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, Ltd., 1981.

Halévy, Élie. A History of the English People in the Nineteenth Century. Trans. E. I. Watkin [vol. 1, England in 1815, trans. E. I. Watkin and D. A. Barker]. 6 vols. 2nd rev. ed. London: Ernest Benn Ltd., 1949–52.

Johnson, Mary Lynn. “Emblem and Symbol in Blake.” Huntington Library Quarterly 37.2 (Feb. 1974): 151-70.

Katz, Eli. Va-ani Avarkhem: A Guide to Birkat Kohanim. [London]: EK Productions, 2004.

Maimonides, Moses (RAMBAM). Mishneh Torah. Trans. Eliyahu Touger. 31 vols. Brooklyn: Moznaim Publishing Co., 1986–2007.

Moskal, Jeanne. “Friendship and Forgiveness in Blake’s Illustrations to Job.” South Atlantic Review 55.2 (May 1990): 15-31.

Quarles, Francis. Emblemes. London: Printed by G. M. and sold at Iohn Marriots shope, 1635.

Robertson, W. Graham. The Blake Collection of W. Graham Robertson. Described by the collector; ed. with an introduction by Kerrison Preston. London: Published for the William Blake Trust by Faber and Faber, Ltd., 1952.

Ross, Alexander. A View of the Jewish Religion Containing the Manner of Life, Rites, Ceremonies and Customes of the Iewish Nation throughout the World at This Present Time; Together with the Articles of Their Faith, as Now Received. Faithfully Collected by A. R. London: Printed by T. M. for E. Brewster and S. Miller, 1656.

Rubenstein, Shmuel. The Synagogue: An Illustrated Analysis of the Aspects of the Synagogue. Bronx: S. Rubenstein, [1972].

Ruderman, David B. Connecting the Covenants: Judaism and the Search for Christian Identity in Eighteenth-Century England. Philadelphia: University of Philadelphia Press, 2007.

Schuchard, Marsha Keith. “William Blake and the Jewish Swedenborgians.” Spector 61-86.

Shiff, Abraham Samuel. “Blake’s Hebrew Calligraphy.” Blake 46.2 (fall 2012): 34 pars.

Spector, Sheila A., ed. The Jews and British Romanticism: Politics, Religion, Culture. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005.

“Tallit.” Encyclopaedia Judaica. 16 vols. Jerusalem: Keter Publishing, 1971-72. 15 [Sm–Un]: cols. 743-45.

Warner, Janet A. Blake and the Language of Art. Kingston: McGill–Queen’s University Press, 1984.

Wicksteed, Joseph H. Blake’s Vision of the Book of Job with Reproductions of the Illustrations: A Study. 2nd ed., rev. and enlarged. London: J. M. Dent & Sons, Ltd., 1924.

Wright, Andrew. Blake’s Job: A Commentary. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972.