note

Two Pictorial Sources for Jerusalem 25

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

I Morton Paley: The Martyrdom of St. Erasmus

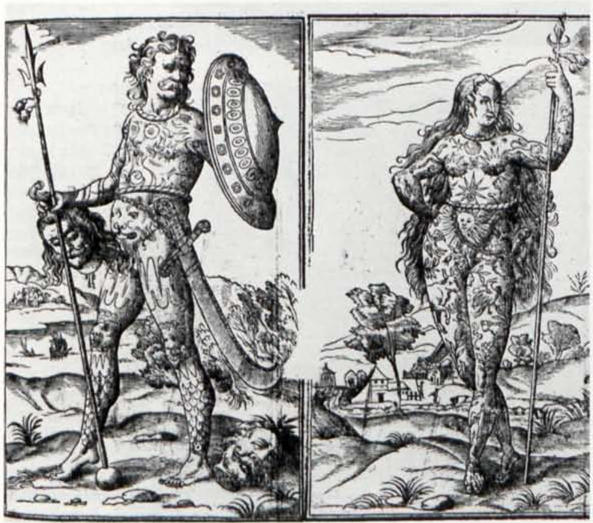

“The difference between a bad Artist & a Good One Is: the Bad Artist Seems to Copy a Great deal The Good one Really Does Copy a Great deal.”1↤ 1 Annotations to Reynold’s Discourses, The Complete Writings of William Blake, ed. Geoffrey Keynes (London: Oxford Univ. Press, 1966), pp. 455-56. (This edition hereafter cited as K.) As Sir Anthony Blunt has shown, Blake really did copy a great deal,2↤ 2 The Art of William Blake (New York: Columbia Univ. Press, 1959). though when he borrowed for one of his own works, the borrowing was seldom without some kind of transformation. Such is the case with the design on plate 25 of Jerusalem [fig. 1].

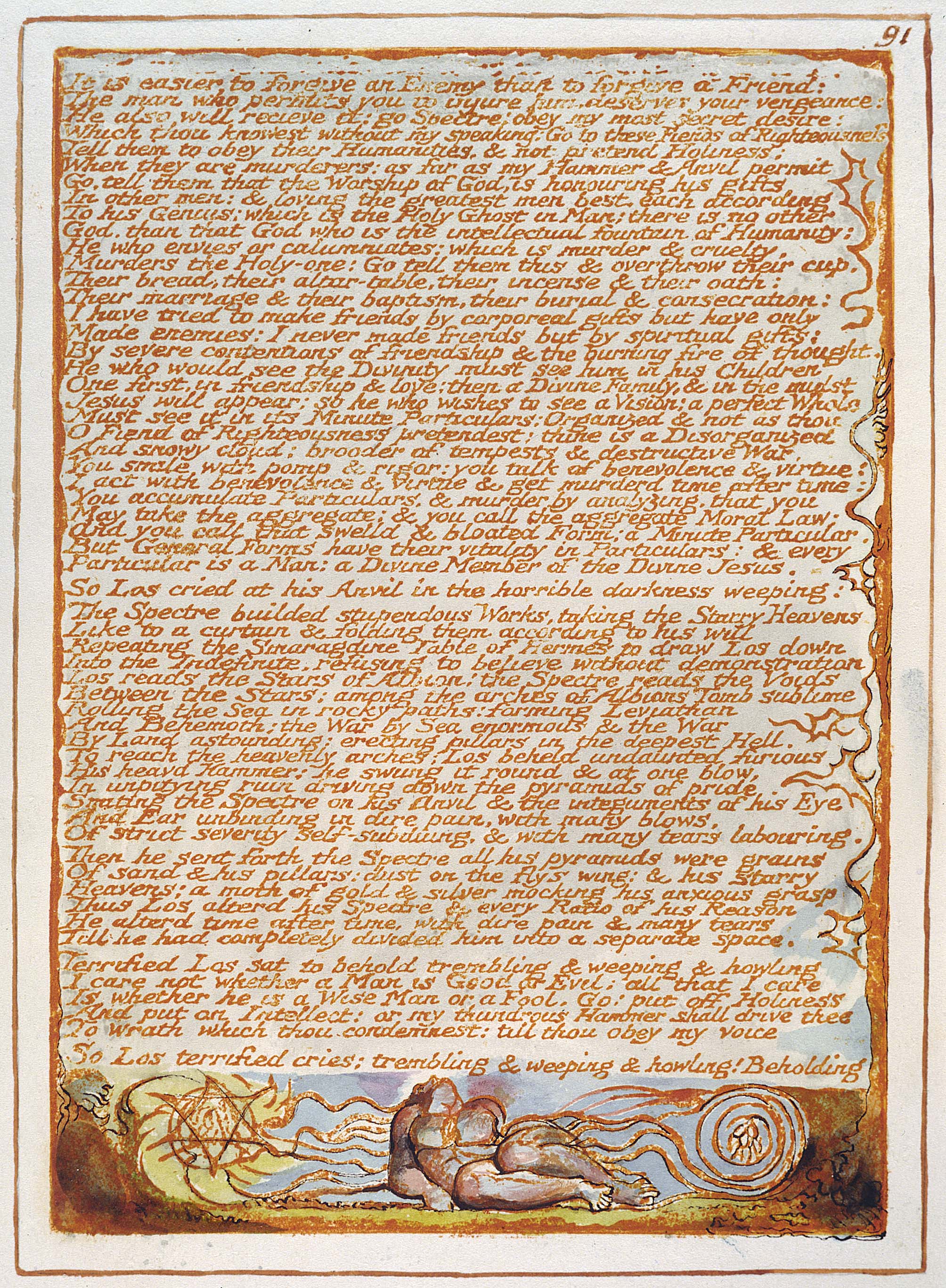

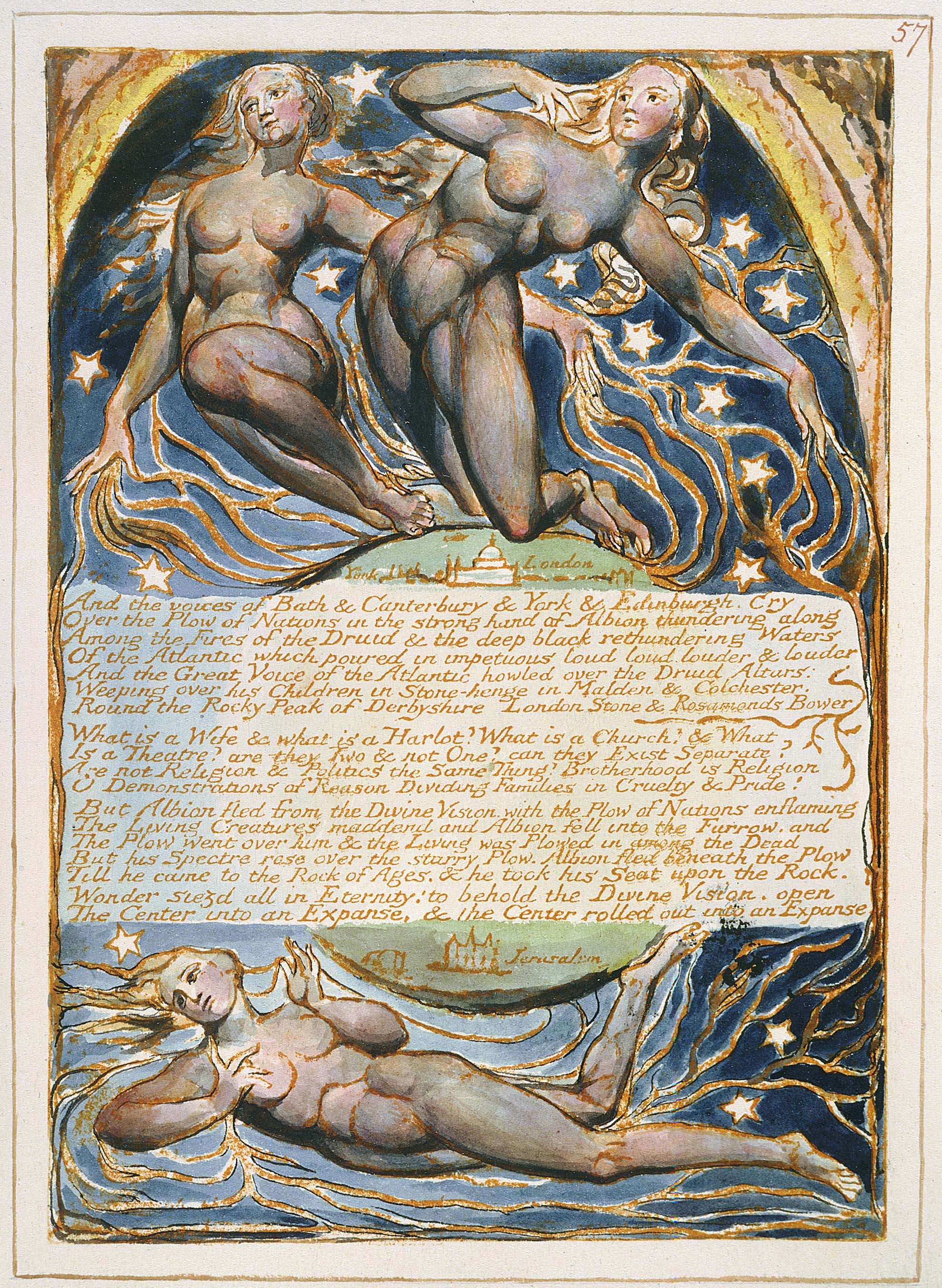

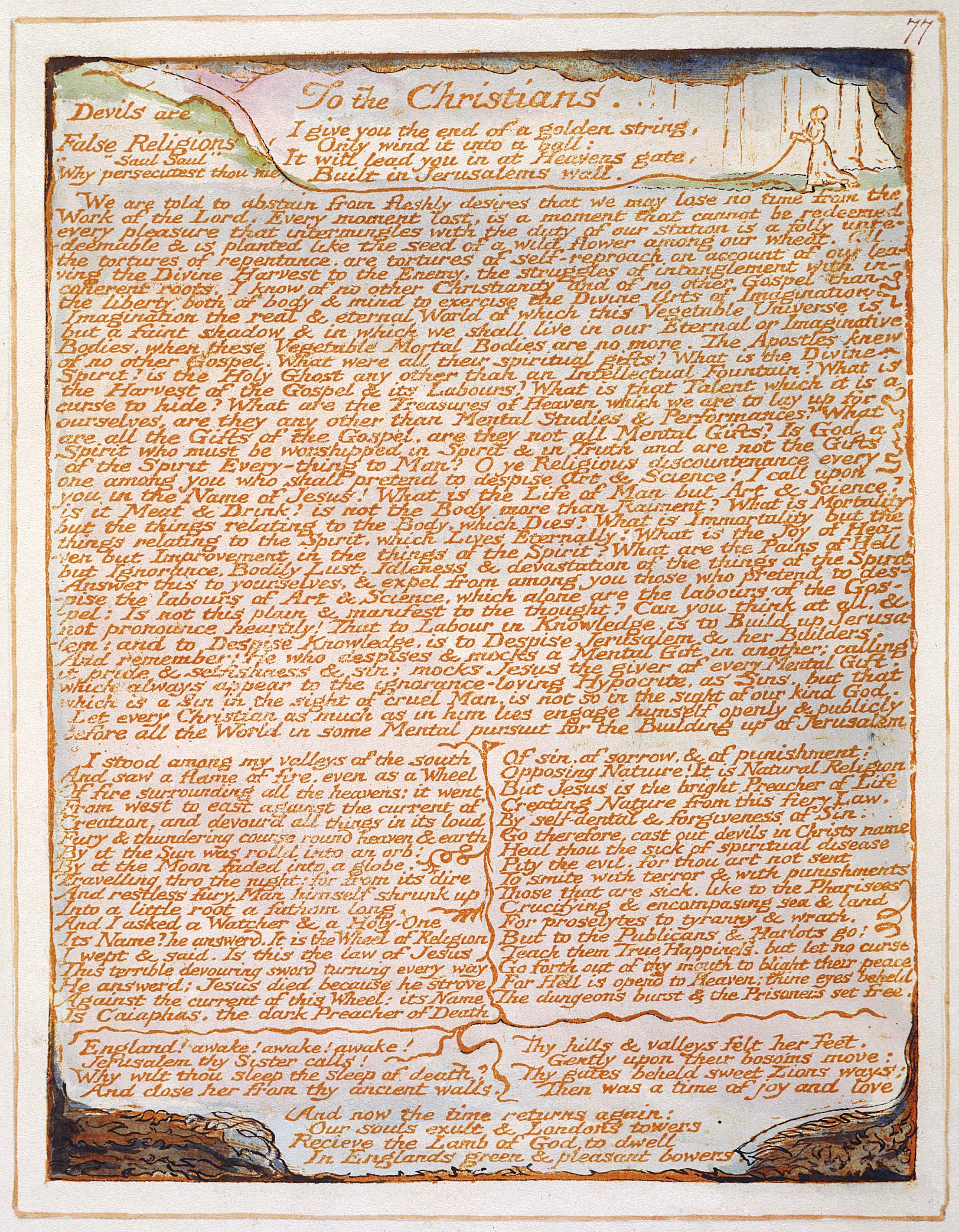

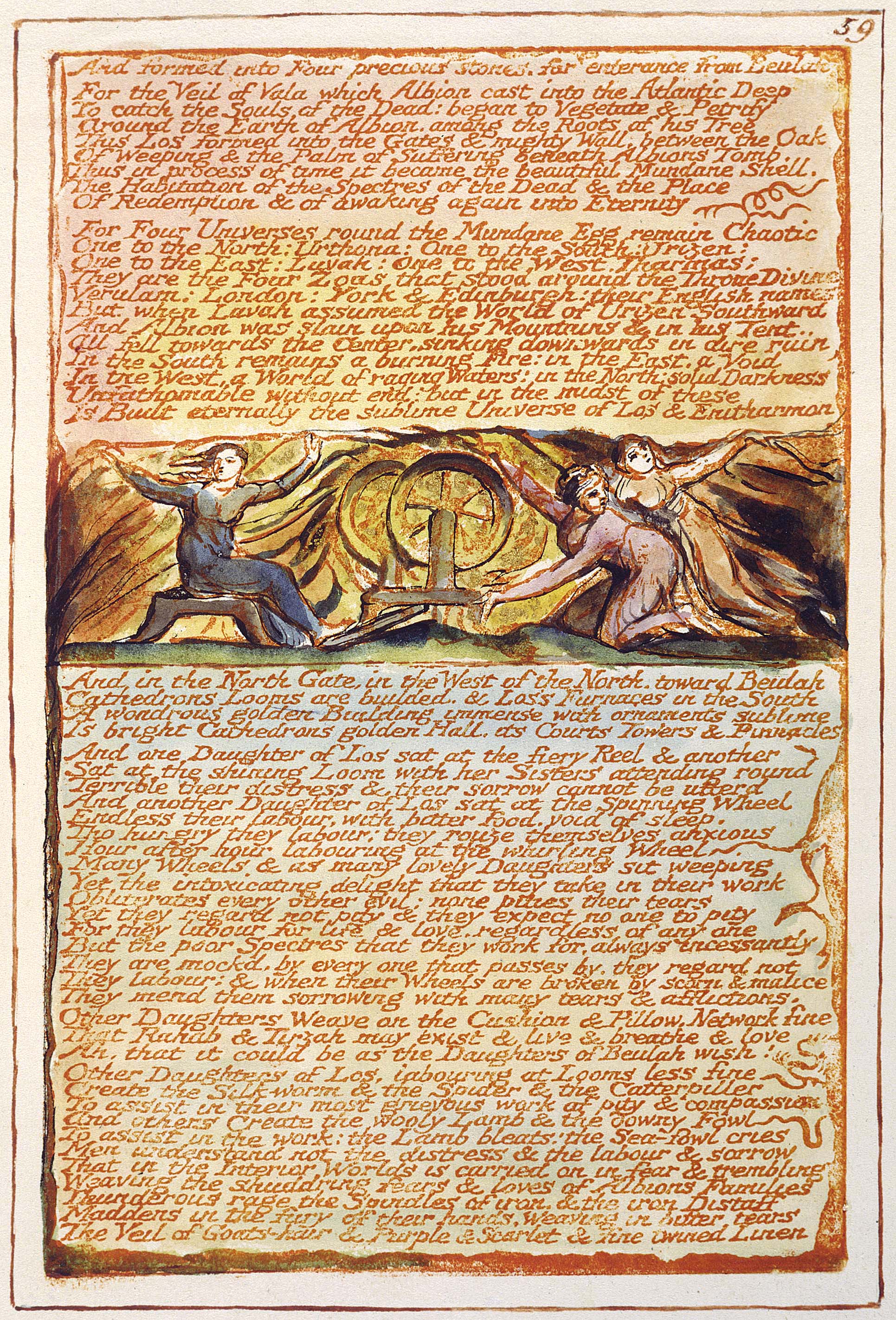

The central figure in this picture is Albion, as we know from the presence of the sun, moon, and stars in his limbs. (Two plates later we are told “ ‘But now the Starry Heavens are fled from the mighty limbs of Albion.’ ”—K 649). He is bound in a position strongly reminiscent of that of the central figure of The Blasphemer 3↤ 3 Also known by the W. M. Rossetti title, The Stoning of Achan, but see Martin Butlin, William Blake / A Complete Catalogue of the Works in the Tate Gallery (London, 1971), p. 45. A similar Michelangelesque posture may be seen in J 91 [fig. 2]. in the Tate Gallery, but here the figure at the right is drawing something out of his body. This action has been variously interpreted as “winding a ‘clue’ of vegetation from his navel,” “drawing out the umbilical cord from his navel” and “disembowelment.”4↤ 4 S. Foster Damon, William Blake: His Philosophy and Symbols (1924; rpt. Gloucester, Mass.: Peter Smith, 1958), p. 470; Joseph Wicksteed, William Blake’s Jerusalem (New York: The Beechurst Press, 1955), p. 155; Butlin, p. 45. Actually, it is all three, for to Blake the bowels and the umbilical cord are equally manifestations of those fibres of vegetation which play so large a thematic role in Blake’s later works. In this particular picture the same fibres that the figure on the right winds out of Albion’s body and into a ball stream down the plate on either side from the fingers of the central female figure. The identity of substance is more apparent in the Mellon copy than in the black-and-white copies, for Blake uses the same russet coloration for fibres of vegetation throughout (compare for example plate 57 [fig. 3], where the russet fibres stream from the fingers of the two female figures above and seem to entrap the one below). This winding of Albion’s “bowels of compassion” (56:34) into a ball is a demonic parody of the activity Blake urges on the reader in plate 77 [fig. 4] with its accompanying picture. Winding and unwinding, weaving and unweaving are indeed among the central motifs of Jerusalem [cf. fig. 5].

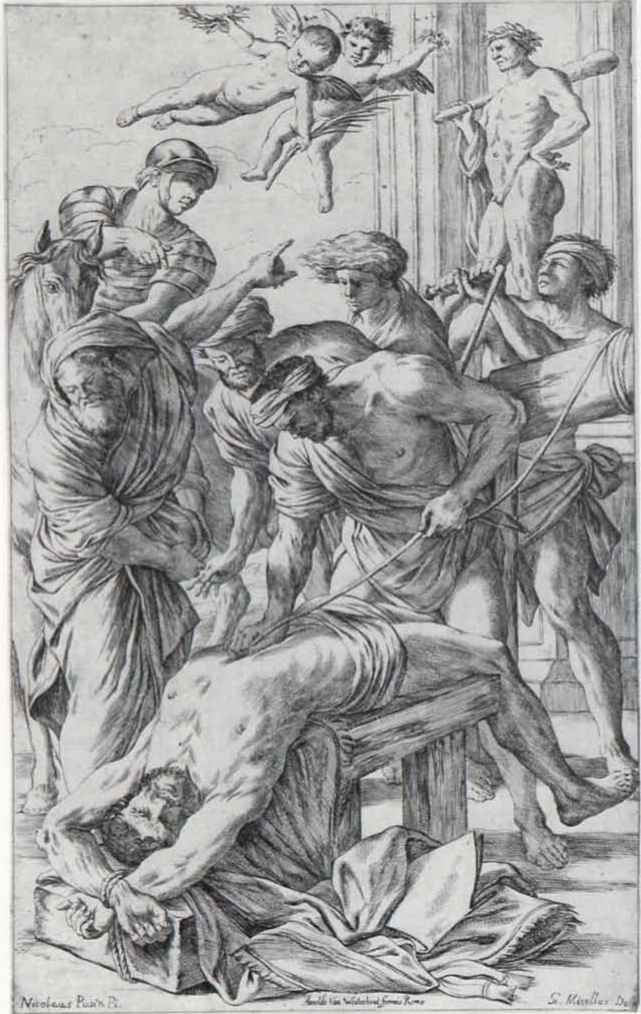

The meaning, then, is thoroughly Blakean. But the depiction of a figure whose

bowels are being unwound is a rather unusual subject, and the existence of just such a figure in a painting by

an artist whom Blake admired suggests that Blake was following his own advice in J 25. The

painting is The Martyrdom of St. Erasmus by Nicolas Poussin. Blake praises Poussin several

times in the Annotations to Reynolds (K 469, 477), and according to Raymond Lister Blake

made a copy of Poussin’s The Giant Polypheme which was engraved by George Byfield c.

1820.5↤

5

William Blake: An Introduction to the Man and His Work (New

York: Ungar, 1970), p. 165. Saint Erasmus was martyred by

having his entrails drawn out and wound on a winch, and although Blake cannot have seen Poussin’s powerful

rendering of this scene in Rome—or in Paris, to which it was removed during the Napoleonic period6↤

6

See Anthony Blunt, The Paintings of Nicholas Poussin / A

Critical Catalogue (London, 1966), pp. 66-68. —he could easily have been familiar with the

version by Joseph Marie Mitelli [fig. 6], an engraving listed as one of Mitelli’s “principal works” by

Michael Bryan in 1816 (A Biographical and Critical Dictionary of Painters and Engravers

[London], II, 76). Blake has of course shifted Poussin’s supine suffering figure to a more Michelangelesque

pose,7↤

7

C. H. Collins Baker suggests that the figure may derive from Flaxman;

see “The Sources of Blake’s Pictorial Expression,” Huntington Library Quarterly, 4

(1940-41), 365. yet the drawing out and winding

of the entrails remain the central conception of both pictures.8↤

8

Miss Deirdre Toomey points out that The Martyrdom of

St. Erasmus was seen and remarked on by Henry Fuseli when he visited the Louvre in 1802. John Knowles

summarizes Fuseli’s view of the painting as follows:

The actual martyrdom of St. Erasmus is one of those subjects which ought not to be told to the eye—because

it is equally loathsome and horrible; we can neither pity nor shudder; we are seized by qualms, and detest.

Poussin and Pietro Testa are here more or less objects of aversion, and in proportion to the greater or less

energy they exerted. This is the only picture of Poussin in which he has attempted to rival his Italian

competitors on a scale of equal magnitude in figures of the size of life; and here he was no longer in his

sphere; his drawing has no longer its usual precision of form, it is loose and Cortonesque; his colour on this

scale has neither the breadth of fresco, nor the glow, finish, or impasto of oil.

—The Life and Writings of Henry Fuseli (London, 1831), I, 270-71.

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

II Deirdre Toomey: Le Tre Parche

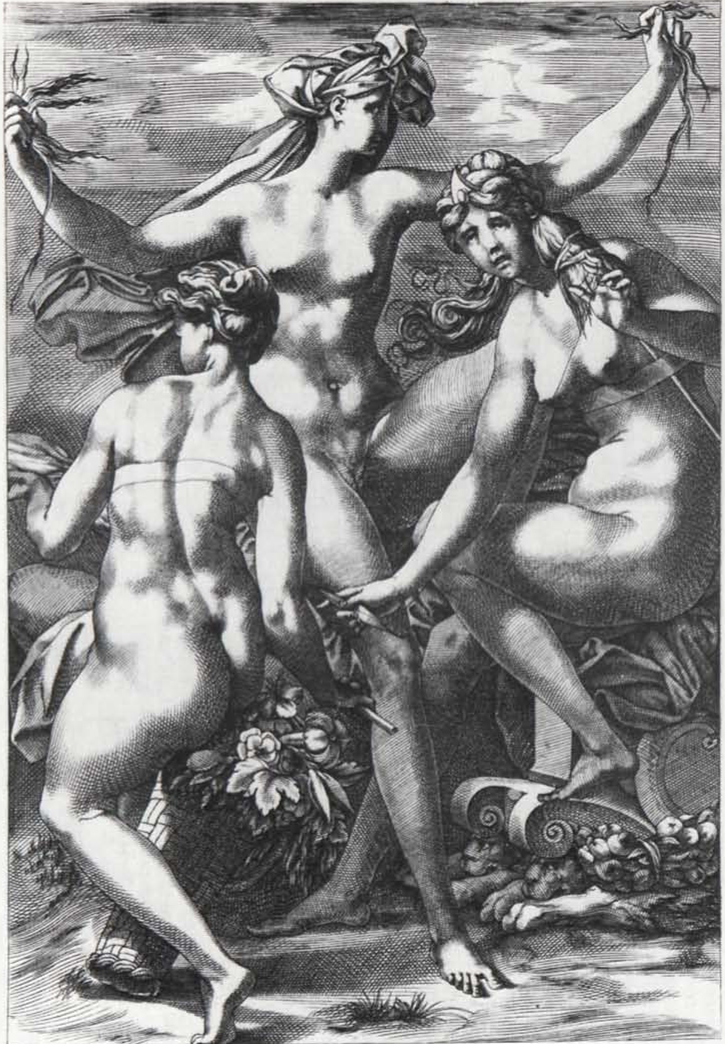

The anonymous engraving after Il Rosso Fiorentino1↤ 1 The Rosso original is lost. known as Le Tre Parche [fig. 7] is usually attributed to Rene Boyvin, a sixteenth century French engraver and designer.2↤ 2 However Yves Metman argues that much of the work hitherto attributed to Boyvin must be assigned to another Fontainbleu engraver, Pierre Millan: this version of the Parche is among those reattributed. See Metman, “Pierre Millan; un Graveur inconnu de l’École de Fontainbleu”, Bibliothèque D’Humanisme et Renaissance (1941), pp. 202-21A [including a supplement of documents]. Boyvin was born in Angers in 1530, worked in Paris and died in Rome in 1598. About 226 prints can be attributed to him, mainly engraved after Il Rosso and Primaticcio. Boyvin engraved two versions of this subject; in the other, also after Il Rosso, the Fates are clothed. According to Robert-Dumesnil a bad copy of the engraving exists with the following inscription in the margin: “Dum terrae Iovis ante pedes fera pensa sorores devolvunt; cave ne tempus mane fluvat.”

The resemblance between this Boyvin print and plate 25 of Jerusalem [fig. 1] in general design and minute detail is striking enough to lead one to conclude that Blake had seen and studied it. The engraving is, and presumably was, extremely rare, and I can find no record of it in Cumberland’s Catalogue; it is possible that a copy was owned by Fuseli, who possessed an interesting collection of Mannerist prints. Two copies of this rare print were acquired by the British Museum in 1850 from the collection of a Mr. Bowerfield.

Blake’s debt to the Rosso design is immediately evident. It can be seen in his use of the unusual pyramidical composition of three female nudes; in the torso and outstretched arms of the central figure and the bundles of cord-like substance that she holds; in the relationship of her arms to the heads of the other two figures; and in the head, features, tear-stained face and hunched pose of the right-hand figure. Indeed the very theme of plate 25 can be seen to be derived from the Parche.

Blake alters the proportion from rectangle to square to accommodate[e] the extra figure. He discards the left-hand Fate for a more compositionally symmetrical adaptation of Michaelangelo’s Night. The central Fate is considerably foreshortened, her sprawling legs are removed and her arms are straightened.3↤ 3 They come to resemble those of the floating female in the Victoria and Albert Allegorical Design with a River God. The right-hand Fate suffers a slight rearrangement of her legs and arms; her hunched pose remains remarkably unmodified. Blake enlarges the picture depth, at the same time concentrating the movement within the design. In the Rosso there is a characteristic tendency towards diffuseness; the strong triangle formed by the three bodies is broken by the outward thrust and gaze of all the figures. Blake’s modifications all tend towards making the design more concentrated, dramatic and energetic. The self-consciousness of the Fates disappears and their potential energy is harnessed by the introduction of the fourth figure and hence an action. In typical Mannerist fashion the diagonals in the Rosso bisect on the pudendum of the central Fate, which is thus the focal point of the design. In plate 25 this central figure is foreshortened and the focal point becomes Albion’s agonized chest. Blake also ignores the merely ornamental parts of the design; the “Testa Divina” head-dresses disappear and blocks of stone are substituted for the draperies, pedestal and basket of flowers.

Blake takes the spinning motif of Le Tre Parche a stage further both formally and iconographically. Instead of the symbolic thread, the females really wind “the thin-spun life,” Albion’s “tender bowels.” This winding of entrails can be seen to be taken from Poussin’s St. Erasmus [fig. 6]: two sources are thus admirably conflated in plate 25. The bundles of flax held by the central Fate also undergo a curious transformation, being enlarged into long willow-like roots. It is important to note that, in taking over and elaborating the Rosso spinning motif, Blake disrupts the process: in the former, the bundles of flax are being spun into thread, in the latter there is no visually logical connection between the “roots” and the entrails.4↤ 4 However if we turn to the text connections can be made: the roots can be seen as Vala’s veil being thrown over Albion’s “deep wound of sin” by the leaning central figure. Blake’s interest in spinning and weaving can be seen elsewhere in Jerusalem, viz., plates 59 [fig. 5] and 91 [fig. 2]. The bands worn by two of the Fates and used as distaff-holders are rather surprisingly ignored by Blake: similar bands are to be seen more than once on Blake’s male figures, viz., Vala p. 60, and, more debatably, on female figures in Jerusalem. The most plausible of these is seen in plate 59, a spinning scene; the bands in plates 5, 8 and 24 are nearer to harnesses of some sort. The female band was a classical device, often used in the Renaissance and available to Blake in countless engravings. Blake’s source for the male band is probably Fuseli.

The sun, moon and stars seen on Albion’s body in this plate can be read as symbolic references to his microcosmic nature:

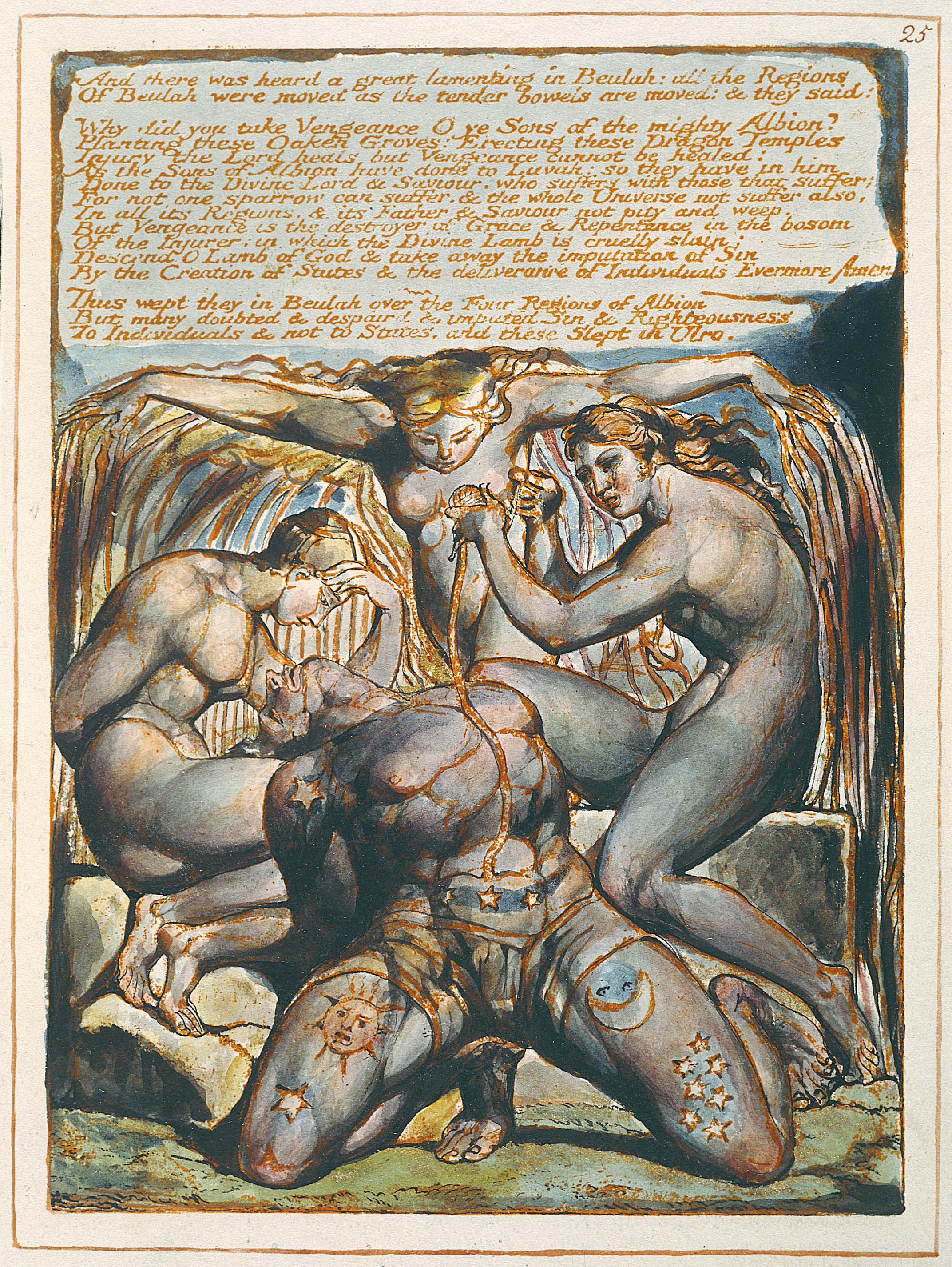

You have a tradition that Man anciently contain’d in his mighty limbs all things in Heaven & Earth: this you received from the Druids.They can also be read, more simply, as primitive decorations, very similar to those seen on the bodies of the Ancient Britons in Speed’s Historie [fig. 8]. Here the ancient Britons are seen as “naked Heroes,” dwelling in “naked simplicity,” though Speed’s Britons are not Blake’s original Britons, “learned, studious, abstruse in thought and contemplation” but, as we see from the heads that they car begin page 189 | ↑ back to top

“But now the Starry Heavens are fled from the mighty limbs of Albion.” (J 27)

Deirdre Toomey will discuss the two states of J 25 in Blake Newsletter 21 (Summer 1972). (Eds.)