Notes

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

BLAKE AND ENGLISH PRINTED TEXTILES

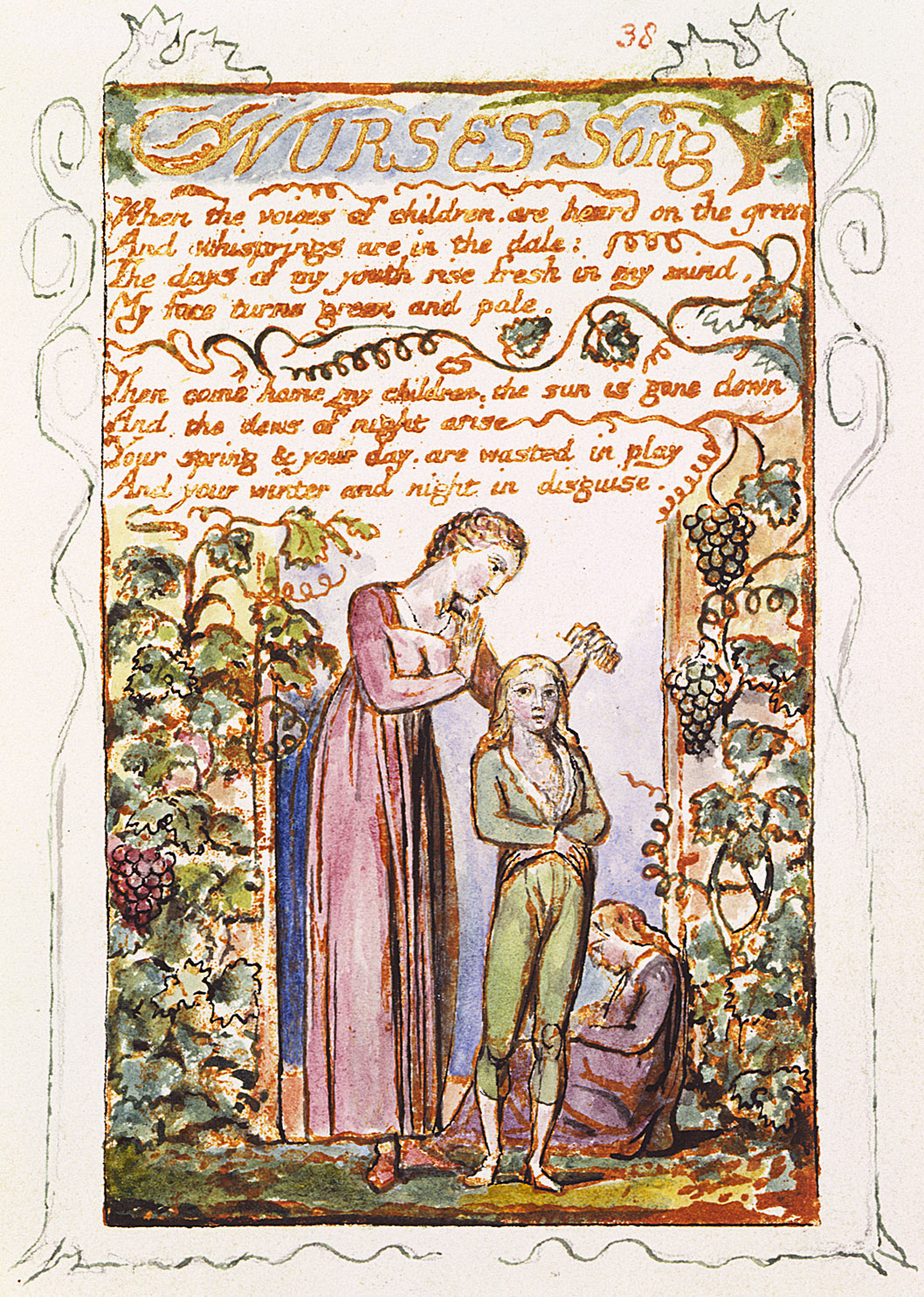

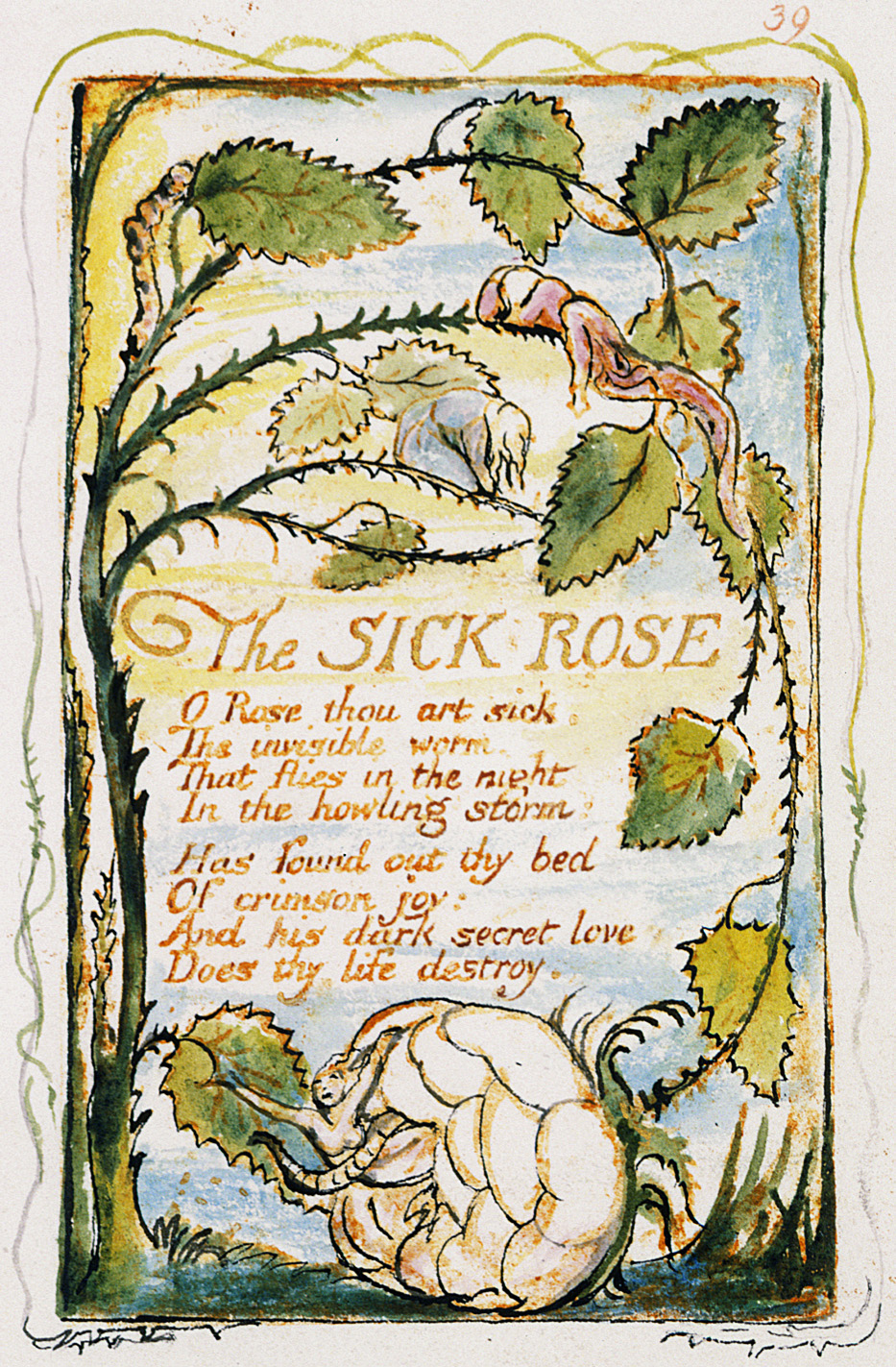

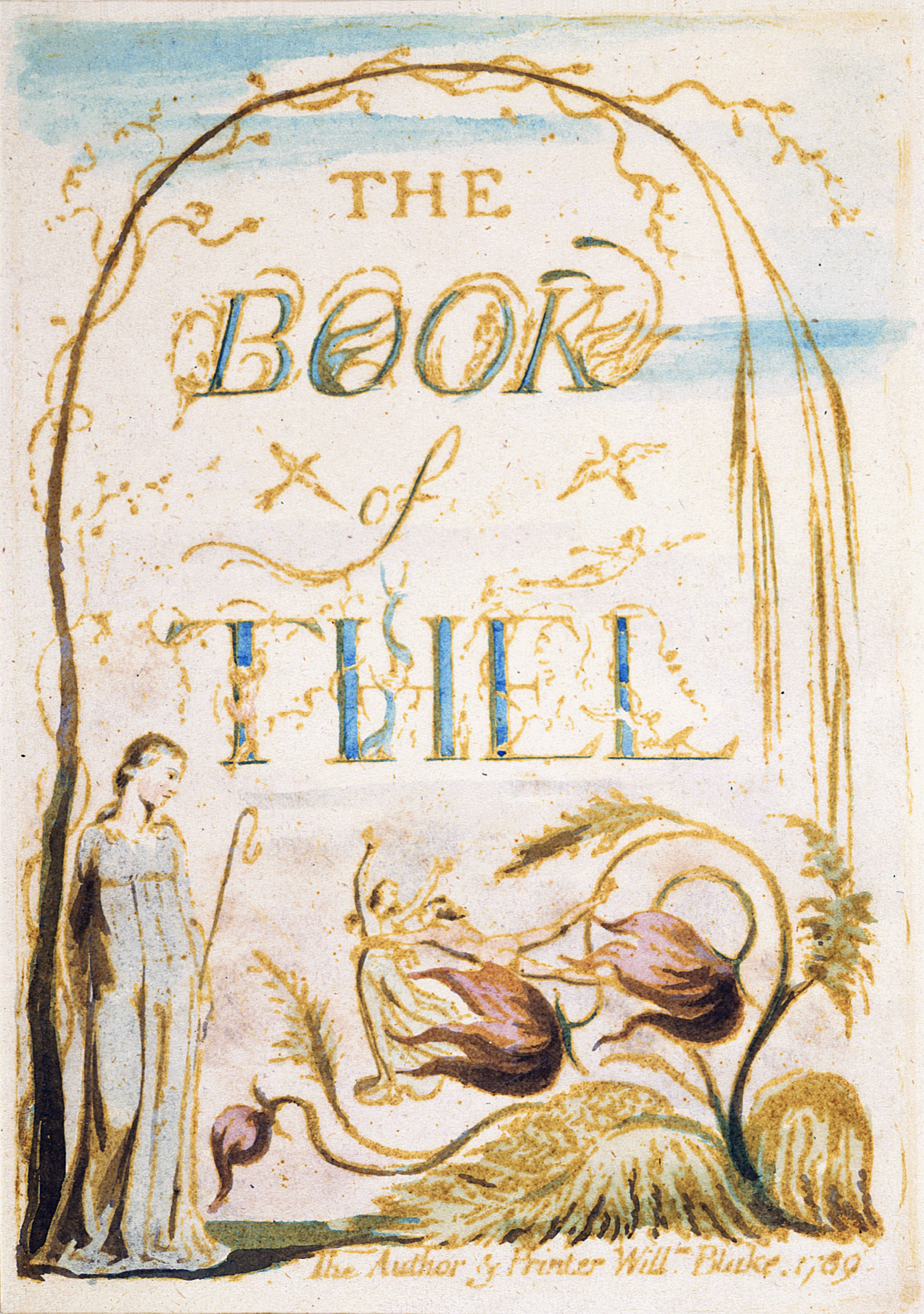

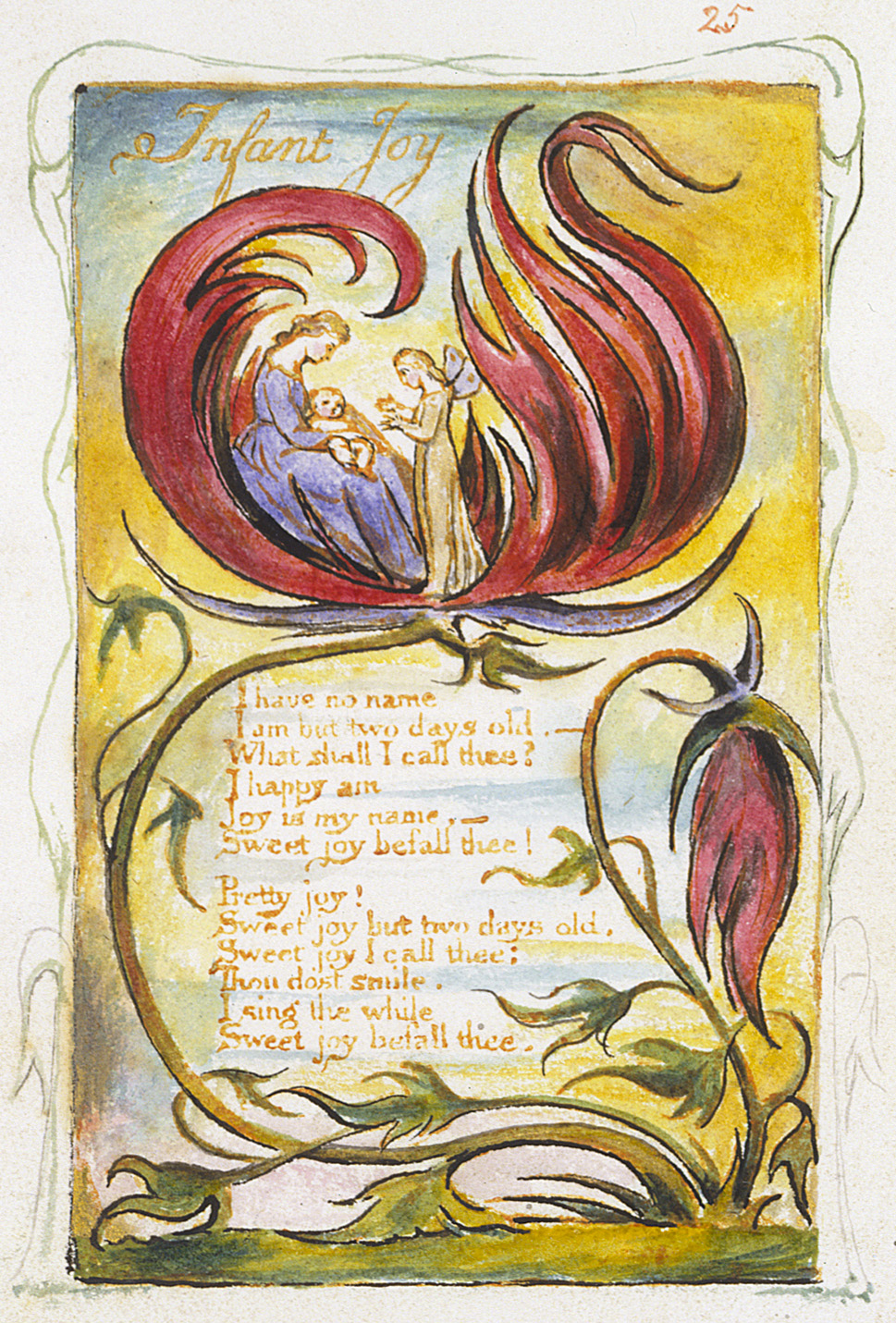

One of the most charming elements of Blake’s designs are his flower forms, particularly those in the Songs of Innocence and Experience, The Book of Thel, and the Paradise Lost series. Blake was no careful observer of Nature, preferring to humanize the material world through imagination, so these flower forms are not exactly “natural.” To modern eyes, they appear abstract and very contemporary in their dream-like suggestiveness. Yet it seems possible that Blake’s inspiration for his floral designs was found in eighteenth century embroidery patterns and textile designs.

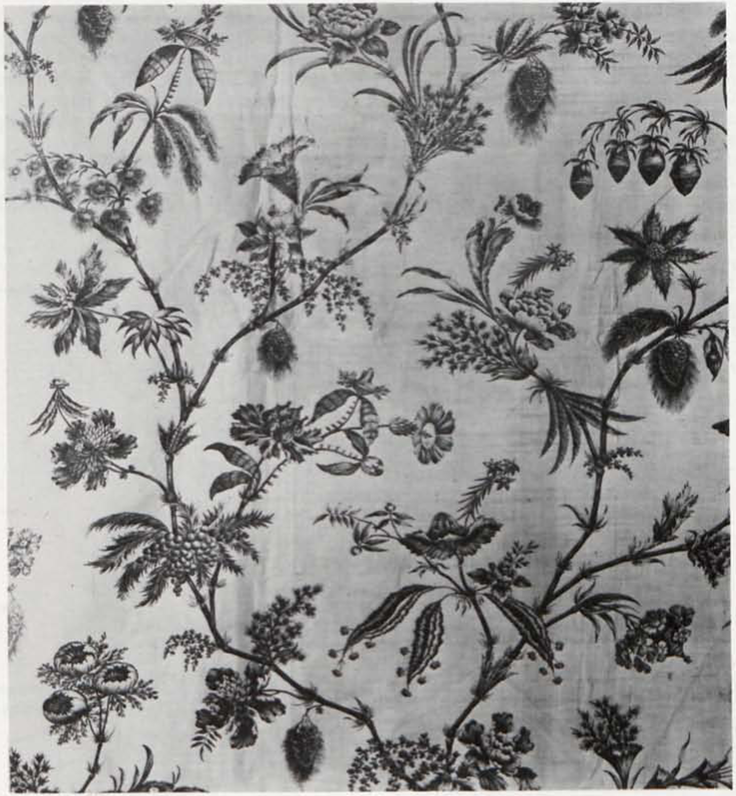

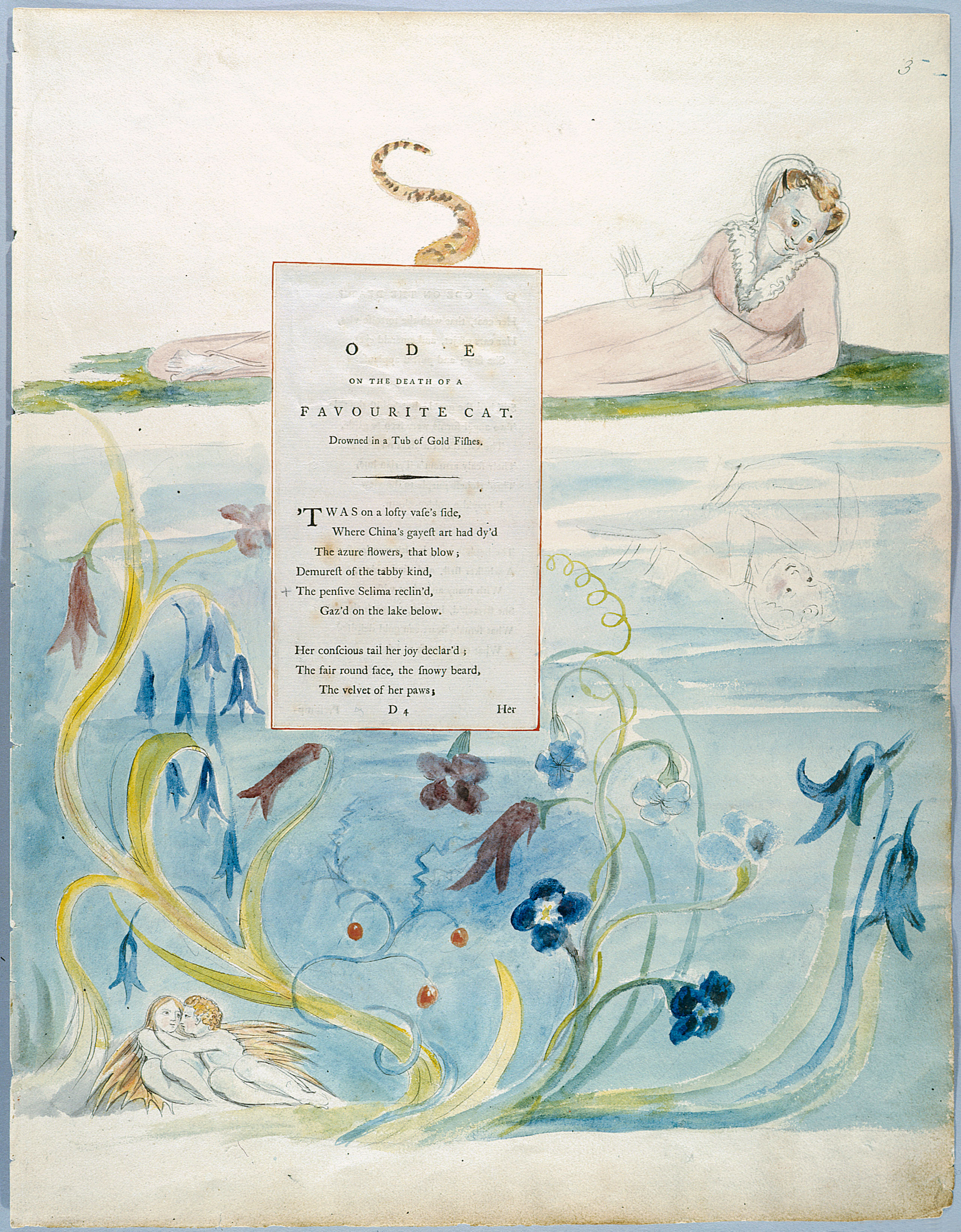

It is known that Mrs. Thomas Butts, wife of Blake’s patron and friend, was expert at needlework, and that Blake probably designed for her a needlework panel called Two Hares in Long Grass. 1↤ 1 Now in the collection of Sir Geoffrey Keynes. See David Binaman, ed., William Blake: Catalogue of the Collection in the Fitzwilliam Museum (Cambridge: W. Heffer and Sons, 1970), pp. 68-69. And it is possible that most women of Blake’s acquaintance, including his wife, engaged in needlework as a pastime. But as a printer, Blake would be also familiar with textile designs through begin page 86 | ↑ back to top the growing English textile-printing industry which—in the mid-eighteenth century—was just beginning to be transformed by the use of engraved copper plates.2↤ 2 See English Printed Textiles (London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1960), p. 2. Thus during Blake’s apprenticeship as an engraver in the 1770s, the districts around London were a center for copper-plate textile printing, a position they were to lose by 1800, by which time Lancashire firms had forced most of the London printers out of business. Pattern books which came to light as recently as 1955 reveal that a particular group of designs using large flowers and birds was characteristically English.3↤ 3 English Printed Textiles, p. 3. Popular designs were also “Chinoiseries” based on the published patterns of Jean Pillement (1760).4↤ 4 English Printed Textiles, p. 3. Blake must have known of these designs, and some of them seem to have been adapted by him. For instance, his design in 1797 for plate 3 of Gray’s Ode on the Death of a Favourite Cat is reminiscent of a plate-printed

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

‘Twas on a lofty vase’s side,begin page 87 | ↑ back to top

Where China’s gayest art had dy’d

The azure flowers that blow. . . .

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

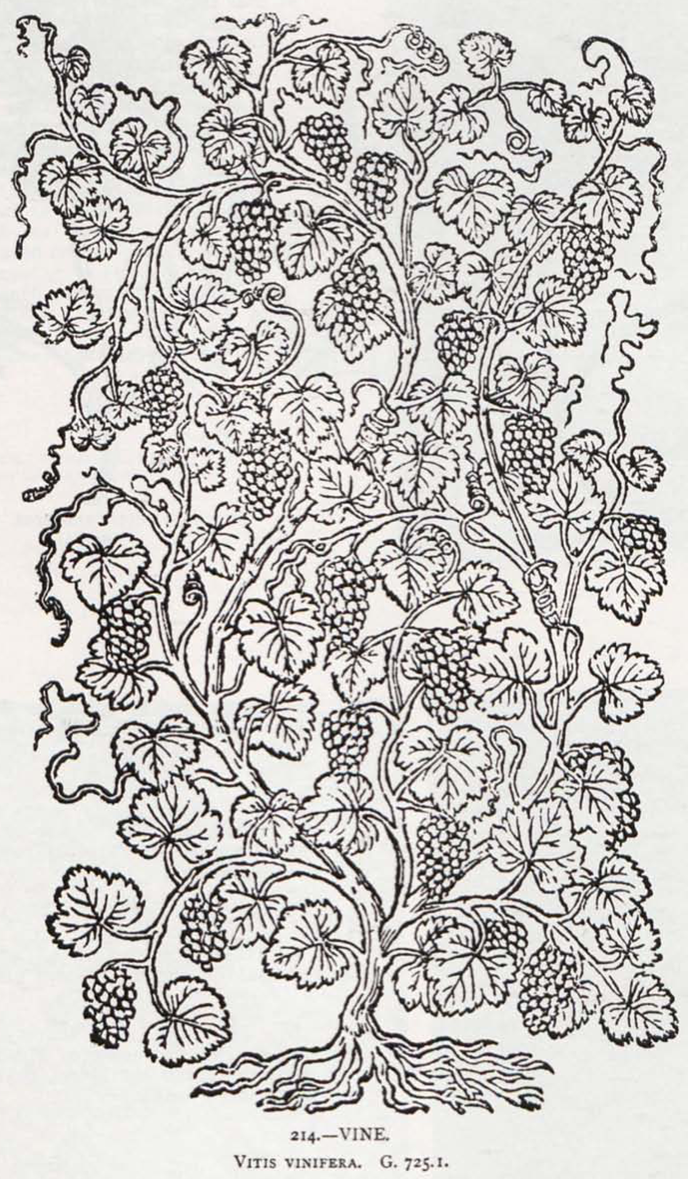

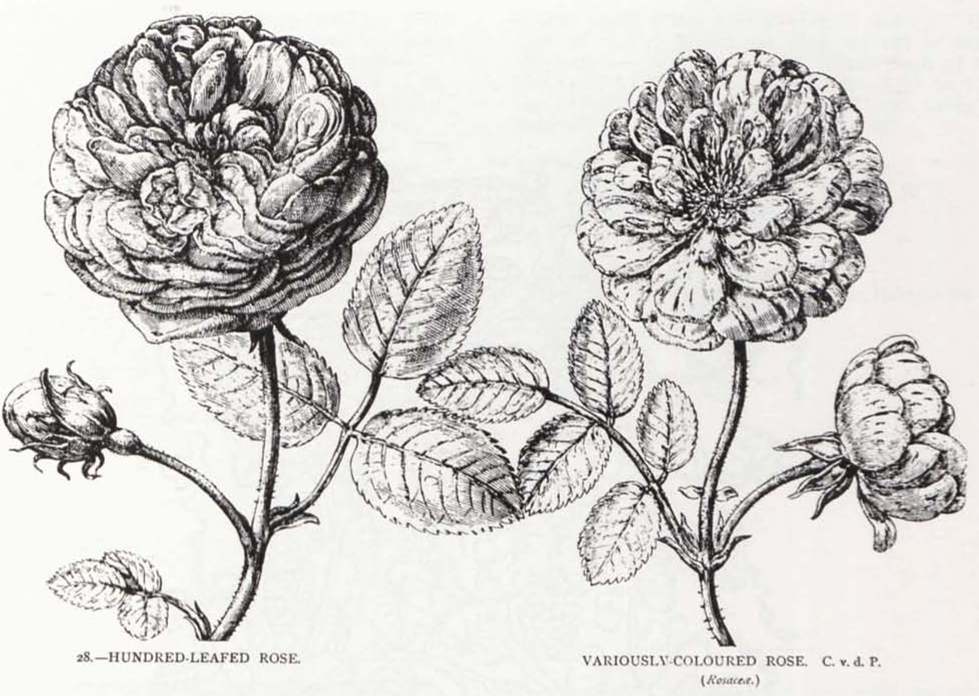

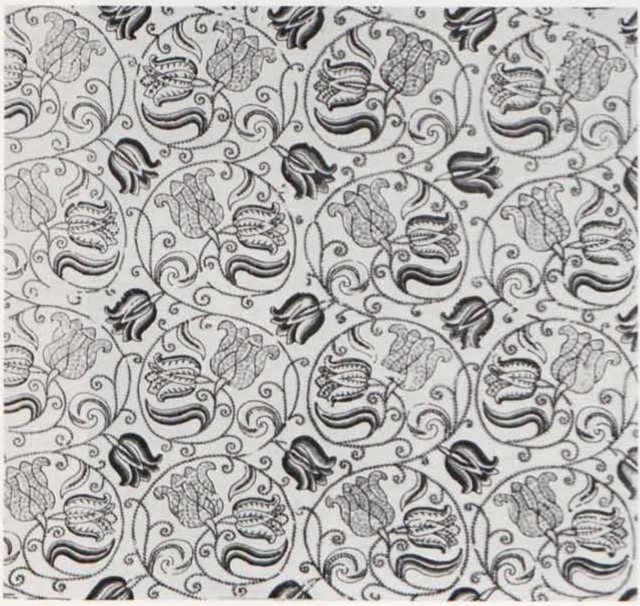

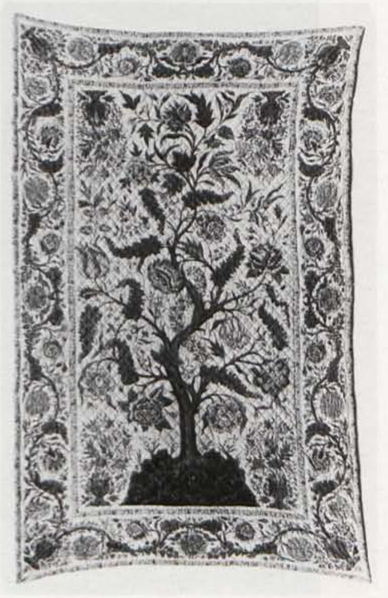

Of course another possible source for Blake and probably the textile designers as well would have been the Herbals of the sixteenth century, books of wood-cuts or engraved drawings of plants which would have been known to anyone engaged in the printer’s craft.5↤ 5 See for example Richard G. Hatton, Handbook of Plant and Floral Ornament (1909 [as The Craftsman’s Plant Book]; rpt. New York: Dover, 1960). Similarities between Blake’s floral patterns and the Herbals can be seen here in illustrations 3 and 4, 5 and 6. A mid-seventeenth century needlework tulip is also illustrated which bears a striking resemblance to the flower in Blake’s title page to The Book of Thel (illus. 7 and 8). Blake’s tulip and leaf designs on Thel’s title page bear even closer resemblances to forms in eighteenth-century Indian chintz (illus. 9). Another needlework tulip recalls Blake’s design for “Infant Joy” (illus. 10 and 11), and anyone who has seen an oak leaf in crewel work will be reminded of Blake’s oak-leaf designs. Many English textile designs were based on designs of Indian chintz, which was so popular in England in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries that the wool industry legislated against its import. The oriental flavor of the animals and botanical forms of some of Blake’s Paradise Lost designs may owe

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

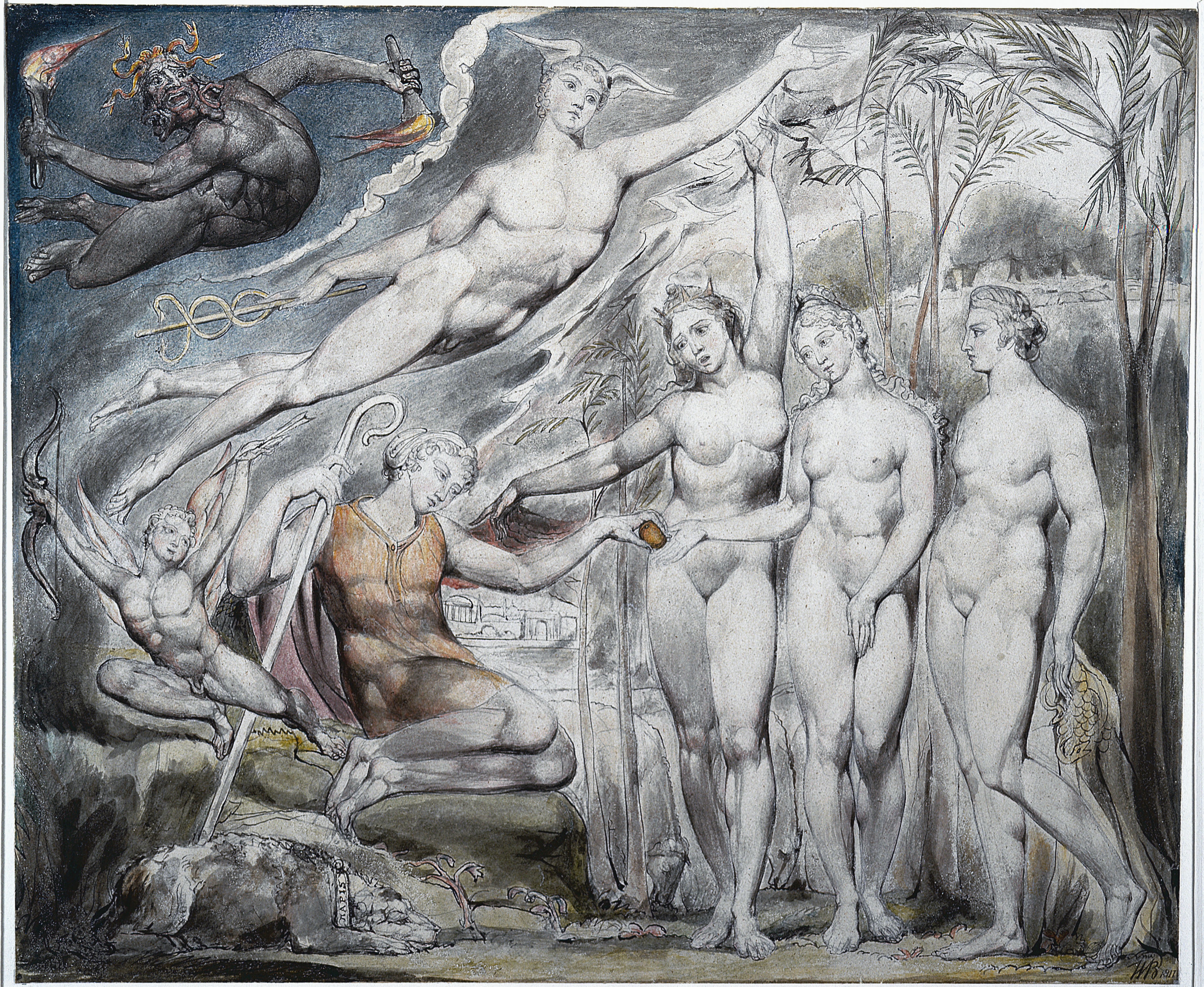

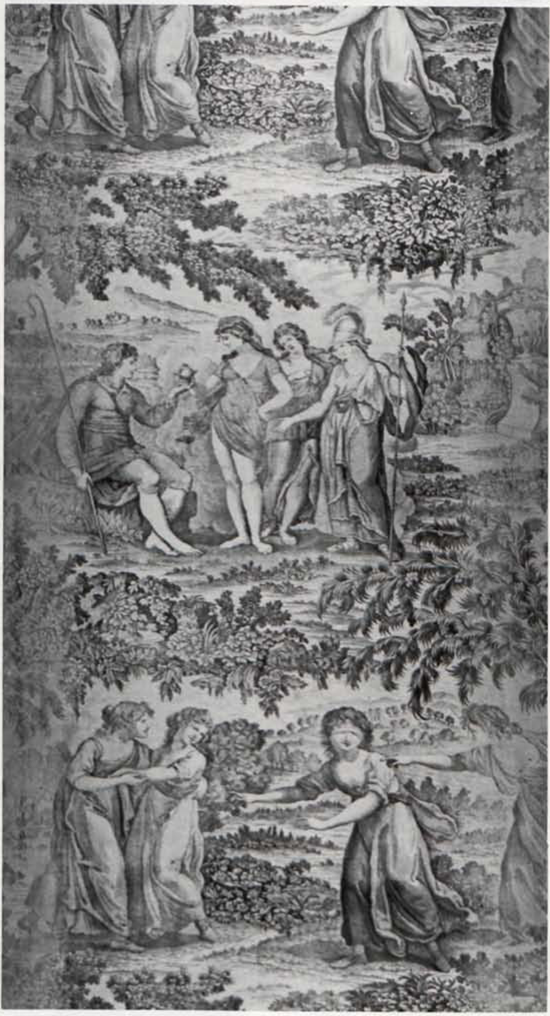

Mythological scenes were also utilized by the English designers of plate-printed cottons, and one of these scenes from a design dated about 1795 bears interesting resemblance to Blake’s own design, The Judgment of Paris, executed in 18177↤ 7 The most obvious similarities lie in the general arrangement of the characters, and the stance of the woman at extreme right. Blake specialists will find the differences as significant as the similarities. (see illus. 12 and 13). Barbara J. Morris, who wrote extensively about the English textile designs when they were first discovered, could not find a source for this design but thought it reminiscent of Stothard.8↤ 8 Barbara J. Morris, “English Printed Textiles, V. Sports and Pastimes,” Antiquee, 62 (Sept. 1957), 253. This is one of nine articles on English eighteenth-century copper-plate textiles and early nineteenth-century roller prints by Peter Floud and Barbara Morris, printed March 1957 to April 1958 in Antiques.

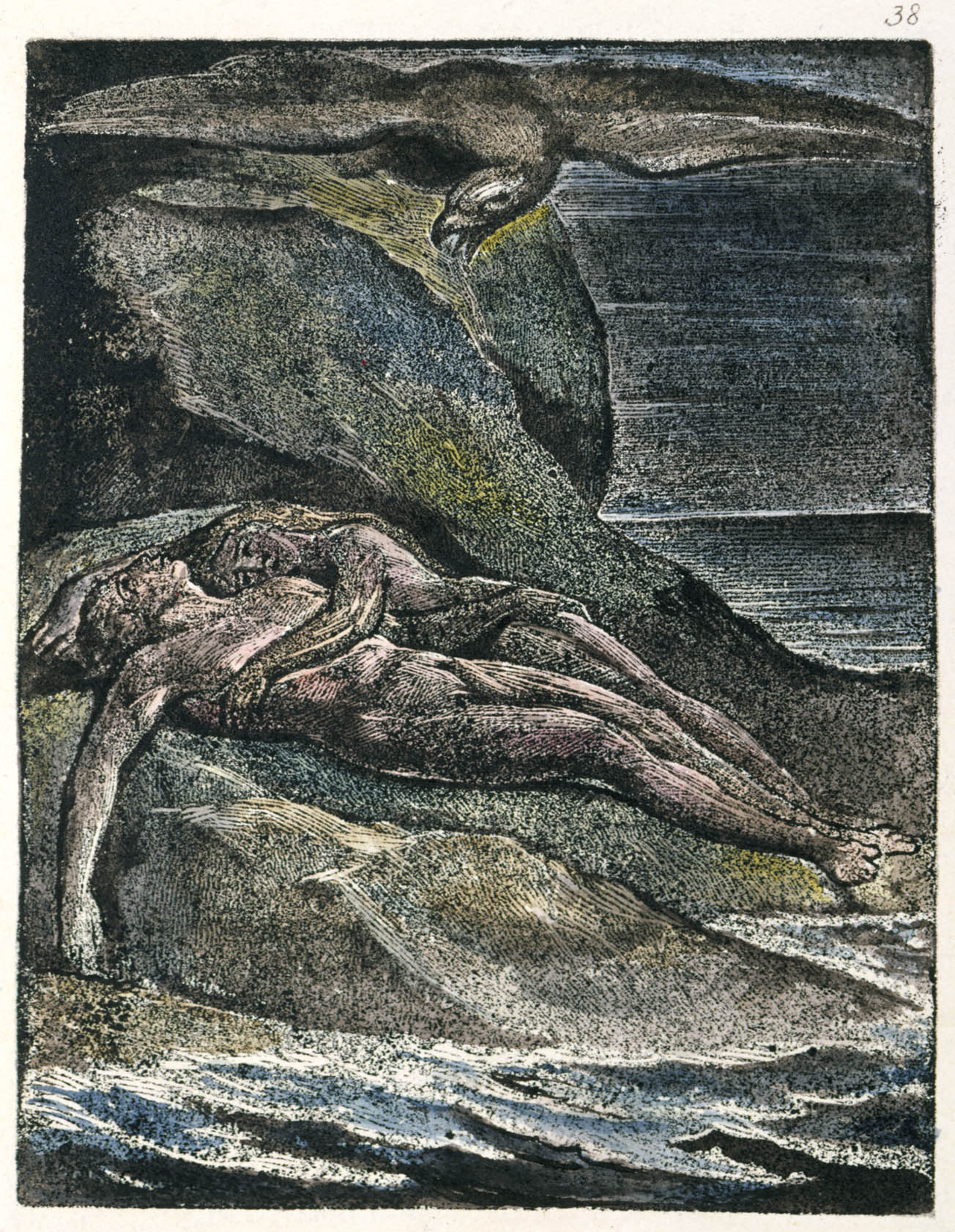

There is no known record of Blake’s involvement in commercial textile design, though there is one existing example of an engraved trade card which he designed for Moore and Co., a firm which manufactured carpets and hosiery.9↤ 9 Reproduced in Ruthven Todd, William Blake the Artist (London: Studio Vista, 1971), p. 26. Since Blake’s brother James was a hosier, and his father had been one, it is not surprising to see that Blake’s design shows a real familiarity with the machinery involved. It seems possible that he would have been familiar with more commercial ventures of this nature than is usually supposed. In the Metropolitan Museum’s collection of tradesmen’s cards is an eighteenth-century printer’s card whose emblem of an eagle closely resembles Blake’s eagle in Milton, plate 38 (illus. 14 and 15).

Since Blake wrote a good deal about his own capacities for drawing and the quality of his “execution,” and since we also know he could draw in any way he chose—realistically or symbolically—his choice of floral motifs and the sources he chose to emulate are of some importance to an understanding of his purpose. It is possible that he chose the iconographically familiar forms of popular textile designs because in this way he reaffirms a language of Art which he firmly believed was available to everyone (“ . . . no one can ever Design till he has learned the Language of Art by making many Finished Copies both of Nature and Art and of what ever comes in his way from Earliest Childhood” [Annot. to Reynolds]). The universality of such forms, which transcend linguistic differences, implies a unity in the human imagination which makes all art and all religions one. The full significance of Blake’s visual symbols continues to be explored by Blake scholars; I have here called attention to a more mundane aspect of Blake’s technique as a designer, yet it may indicate the attention and importance attached to “Minute Particulars” as the foundation of divine Vision. As Blake wrote in the Annotations to Reynolds, “Minute Discrimination Is Not Accidental All sublimity is founded on Minute Discrimination.”

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]