article

begin page 32-33 | ↑ back to topThe Critical Reception of A Critical Essay

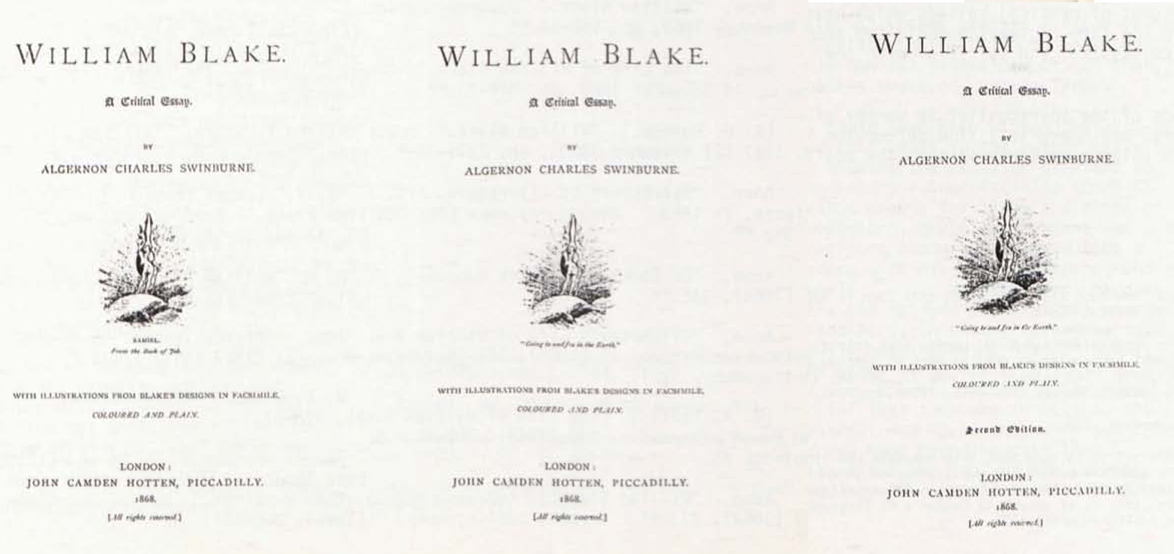

The title pages from the first and second issue of the first edition are reproduced from the collection of Robert N. Essick, and with his permission.

In The Bookseller for 1 February 1868 appeared the following advertisement by John Camden Hotten: ↤ 1 All known title-pages, however, are inscribed William Blake / A Critical Essay. ↤ 2 The Athenaeum’s review actually appeared on 4 January.

“Mr. Swinburne’s New Book” Notice—the New Book by Mr. Swinburne, ‘William Blake, Artist and Poet’1 is ready this day. Thick 8 vo. cloth, gilt, numberous coloured illustrations, 16s. *A most extraordinary book, and one of the finest pieces of prose composition which have appeared during the present century. See the Athenaeum, 11 January 1868.2The critical reception of Swinburne’s book is a subject that has been virtually ignored up to the present time. Only two reviews are mentioned in William Blake in the Nineteenth Century by Deborah Dorfman, and one of these is unaccountably not a review of Swinburne’s book but a short essay by W. A. Cram which mentions neither Swinburne nor his William Blake.3↤ 3 Cram’s essay appeared in The Radical (Boston), 3 February 1868, pp. 378-82. Clyde Kenneth Hyder lists seven reviews in Swinburne’s Literary Career and Fame4↤ 4 Durham, N.C., 1933, pp. 133-34. ; the discussion of these is brief and, appropriately, centers on Swinburne’s literary reputation rather than Blake’s. There are actually at least nine reviews, all published in 1868, forming an interesting spectrum of mid-Victorian critical opinion on Blake. At times we find the reviewers longing wistfully for the less threatening Blake presented by Gilchrist, and there occurs the begin page 33 | ↑ back to top predictable dismissal of Blake’s visionary qualities. Still, two of the reviews are highly discerning ones, and even the more negative reviewers had to take Blake seriously. Swinburne had made great claims for Blake as both poet and artist. After this, Blake might still be condemned, but he could no longer be ignored.

Perhaps the first review to appear was that in The Athenaeum for 4 January 1868 (No. 2097), pp. 12-13. The anonymous reviewer takes what might be called an intermediate position. He does not accept Swinburne’s high claims for Blake’s art, and he finds “a strange contradiction of feeling and outrage of that taste which we should expect to be innate in Blake, which, nevertheless, affected his Art of all kinds, pictorial as well as poetic, and seemed to be derived from the very root of his genius, inexplicable and marvellously offensive.” The reviewer is sophisticated enough to realize that some of Blake’s views had been distorted in order to make them conform to Swinburne’s—“What the subject and his critic mean by ‘rebellion’ may not be the same”—and he rightly sees the argument for “the alleged ‘uselessness’ of the Fine Arts” as Swinburne’s rather than Blake’s. This reviewer, though critical of both author and subject, has enough sympathy for the enterprise to make the book seem worth reading. The same cannot be said of the Saturday Review’s critic, who has been identified as J. R. Green, “clergyman, historian, and librarian at Lambeth Palace.”5↤ 5 M. M. Bevington, The Saturday Review 1855-1868, New York, 1941, pp. 223, 349. The review appears in the issue for 1 February 1868, pp. 148-49. The Saturday had in 1866 published John Morley’s savage review of Swinburne’s Poems and Ballads; Green must have been chosen to do a similar job on William Blake. “Have you seen the Saturday on me and Blake?” wrote Swinburne to W. M. Rossetti. “Of course I’m dead.”6↤ 6 The Swinburne Letters, ed. Cecil Y. Lang (New Haven, 1959), I, 289 (letter dated 1 February 1868). This edition will be cited as Letters.

begin page 34 | ↑ back to topGreen pretends to believe that Swinburne wrote the book in order to avenge himself on Philistine critics. “Free as the rest of the world may be to toss them, after a moment’s perusal, to the butter-shop, Mr. Swinburne must have felt a secret satisfaction, as he penned these three hundred pages, in the thought that his reviewers would at least be bound to read him.” The attack, unfair as it may be, has some point, for Swinburne’s dithyrambic style is vulnerable to thrusts like

How does it help us to appreciate the Songs of Innocence to know that ‘every page has the smell of April,’ or that if ‘these have the shape and smell of leaves and buds,’ the Songs of Experience ‘have in them the light and sound of fire and the sea’? This is just the sort of vapid twaddle which has hitherto passed current for criticism in music alone, where we ask for some explanation of the relation of Sterndale Bennett to Mendelssohn, and are told that the first is a fountain and the second is a star.Green does express admiration for Blake himself, but professes anger at Swinburne’s having used his subject for “a ‘shy’ at ‘Philistia’ and morality.” According to Green, “The wrong done is done to Blake. Strange as his life was, stranger as was his talk, we are among those who are ready to bow down before one who was at once a great artist and a great poet.”

By far the most interesting and thoughtful response to William Blake came from the Fortnightly Review for February 1868 (pp. 216-20). The author was Moncure D. Conway, who was later to write a biography of Thomas Paine. Conway had been born in Virginia and raised as a Methodist, but he had gone on to attend the Harvard Theological School and to become a Unitarian. He was an active abolitionist and a friend of Walt Whitman’s; it was Conway who acted as the friendly intermediary in the correspondence that led to the first volume of Whitman’s poems to be published in England, a selection edited by William Michael Rossetti and published in 1868 by John Camden Hotten in an edition “Uniform with Mr. Swinburne’s Poems.”7↤ 7 Hotten’s “New Book List” for 1868; this item is followed immediately by William Blake. Conway had emigrated to England, become minister to a Unitarian congregation at Finsbury, and had defended Swinburne in the New York Tribune in 1866. In return he received a friendly letter in which Swinburne discussed Whitman, Blake, sea bathing, and other matters of mutual interest. Clearly the Fortnightly wanted a critic friendly to Swinburne just as the Saturday had wanted an unfriendly one, and it is ironical that by January 1868 the editor of the Fortnightly was none other than John Morley, now grown friendly to Swinburne and his works.8↤ 8 Morley’s predecessor was G. H. Lewes, also friendly to Swinburne: Lewes had wanted to publish part of William Blake in the Fortnightly, See Letters, I, 149; VI, 349-50; also W. M. Rossetti, Rossetti Papers (New York, 1903), pp. 243, 245. Indeed, the original choice of reviewer may have been Rossetti himself, for Swinburne and Rossetti had discussed the idea of the latter’s reviewing William Blake for an unnamed periodical; the idea was dropped because Rossetti felt too closely associated with the book, which in the end was dedicated to him.9↤ 9 See Letters, I, 284. Conway proved a good choice, for he not only wrote what George Meredith termed a “eulogistic” review but also provided a critical perspective of his own.

Swinburne’s critical strategy is, in effect, to re-create the effect of Blake upon his own sensibility in a rush of euphoric language. Inevitably he transforms Blake’s major themes into Swinburnian ones, just as in a quite different way Yeats was to produce a Yeatsean Blake a quarter of a century later. Conway does not contradict Swinburne but he does draw upon his own experience of religious dissent and republican radicalism to provide certain insights which Swinburne does not. For example, when Swinburne refers to “the type-yard infidelities of Paine” Conway remarks: ↤ 10 It’s interesting to note that this anecdote was circulating among Paine’s admirers before the publication of Gilchrist’s Life, published in 1863—the year in which Conway emigrated to England. The story is of course in Tatham’s MS biography, but this was not published until 1906.

. . . The first time I ever heard the name of William Blake mentioned, was on the occasion of an assemblage of the friends of Thomas Paine in a city of the Far West, to celebrate the anniversary of his birth. He was there named with honor as a faithful friend of Paine, whom he had rescued from his political pursuers10; but no one in the meeting seemed to have any further association with Blake. Immediately after the disciple who made this allusion, there arose a ‘spiritualist’, who proceeded to announce that the work of Paine was good, but negative; he was the wild-honey-fed precursor of the higher religion; he prepared the way for the new revelation of the Spirits. So close did Paine and Blake come to each other again, without personal recognition, in the New World, where each had projected his visions. America was, indeed, the New Atlantis of many poets and prophets: Berkeley, Montesquieu, Shelley, Coleridge, Southey, and many others, saw the unfulfilled dreams of Humanity hovering over it; but thus far only the dreams of Paine and Blake have descended upon it—that of the former in its liberation from the governmental and religious establishments of the Old World—that of Blake, in the re-ascent of mystical beliefs which have taken the form of transcendentalism among the cultivated, and spiritism with the vulgar.The episode of the spiritualist is worthy of Henry James, and there is a fine perception here of, to use a later writer’s phrase, the politics begin page 35 | ↑ back to top of vision. In making his journey from Southern Methodism to a Unitarian chapel in the north of London, Conway had allied himself with a nonconformist[e] tradition in some ways similar to Blake’s. This accounts for his ability to explain Blake’s theology. For example, Swinburne had declared that Blake’s belief “That after Christ’s death he became Jehovah” was “the most wonderful part of his belief or theory.” Conway observes:

But this would seem to be the logical necessity of his position, supposing that the place and not the nature of Jehovah is meant . . . . A religion victorious in any country over the previous religion of that country, outlaws the divinities of the conquered rival religion, and gradually converts those divinities into devils. The serpent was worshipped as a god before it was cursed as a devil. The god Odin is now the diabolical wild huntsman of the Alps; and every Bon Diable, clad in fruitful green, may trace his lineage to Pan. Jehovah, whom so-called Christianity worships still even under the name of Christ, really crucified Christ, and Christ is the leader of the outlawed Gods—theologically, devils—of Nature. Pharisaism, now surviving as Morality, represents the dominion of Jehovah; that Jesus, the Forgiver, overthrows, restoring the passions and impulses to freedom and power.This is a strikingly successful explanation of Blake’s gnomic statement; even the one point that seems somewhat wrong, the use of the term “Nature,” seems less so when we remember that Conway is speaking of a passage in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, not of Blake’s later attitude toward Nature. Blake would no doubt have used the word “Energy,” while Conway’s idea of Nature is perhaps tinged with Emersonian connotations.

Although Conway praises William Blake as “a very important contribution to both the poetical and philosophical literature of our time,” he is nevertheless aware of certain lacks.

It could have been wished that Mr. Swinburne had felt equal to the rather heavy task of showing the relation of Blake to Swedenborg. Superficially there is reason enough for Blake’s dislike of Swedenborg, whose temperament was without poetry or humour, and acted like a Medusa upon his hells, heavens, and angels . . . . Nevertheless, hard as were the fetters of Calvinism upon him, Swedenborg, in sundry passages, ingeniously overlooked by his followers, had the germs of an optimist faith in him. He sees spirits in hell quite happy in a belief that they are in heaven, and giving thanks. And where they were suffering he saw hope brooding over them . . . . With Blake the soul of the current theology which still haunted Swedenborg is utterly dead and trampled on; but he has not been able to rid himself of its body of language and images, however he may force these to strange and suicidal services.Here again we see an awareness of Blake’s complex relationship to his tradition, an awareness rare before our own century. Also, Conway is one of the few contemporary reviewers to appreciate the facsimile illustrations to A Critical Essay, remarking that “the publisher, and the artist who has reproduced in it some of the most characteristic works of Blake’s pencil, have spared no pains to present worthily things of which poor Blake, sitting in his comfortless room, said ‘I[e] wrote and painted them in ages of eternity, before my mortal life.’ ”

The next dated review to appear is that in The Examiner for 8 February 1868, pp. 84-86. The anonymous critic praises Swinburne condescendingly for having undertaken the unattainable task of making Blake’s works intelligible. There is nostalgia for Gilchrist, who did no such thing. “Mr. Gilchrist . . . was too sensible to the faults and follies of the man, and too honest to deny or ignore them.” Blake was of course a writer of beautiful lyrics, “some of which are worthy of being read on the same day with the lyrics of Keats and Shelley.” But he over-reached himself, much as Mr. Swinburne, who “like the subject of his euology . . . would seem to be possessed of a lust of paradox, insatiable and irrepressible.” The comments on Blake’s symbolic works are worthy of Urizen himself, as the reviewer describes Blake “in his wanderings through trackless space and his allegoric readings of the battle between abstract good and evil, his nightmare transfigurations of darkness into light and light into darkness,—his revolting phantasies regarding sex, and his unconscious blasphemies of all that is called God and that is worshipped—.” The Examiner’s writer is unable to distinguish Swinburne’s views from Blake’s, and part of his review (unlike the Athenaeum’s) is devoted to attacking views on art that were not Blake’s at all. Swinburne had defended “art for the sake of art”; The Examiner replies with a defense of art in the service of religion. This review shows no particular knowledge of Blake and merely repeats commonplace assumptions.

One review which appeared at about this time now has a merely spectral existence. The Imperial Review, a weekly that was published for only two years, has so far been located only in the British Museum; but the Museum’s copies were, we are informed, destroyed by bombing in World War II.11↤ 11 The British Union Catalogue records 105 numbers published from 5 January 1867 to 26 December 1868. It is to be hoped that a copy of this review may one day be found elsewhere, but meanwhile we do have a portion of it reprinted in an American periodical, The Round Table (No. 161, 22 February begin page 36 | ↑ back to top 1868, pp. 124-25). The Imperial accuses Swinburne of wishing to totally sever the good and the beautiful, but then, in a strange reversal of expectation, goes on to condemn Blake and praise Swinburne. “What has Blake to do with Swinburne? Blake, whose mad uncouth rhapsodies are such a contrast to our latest poet’s voluptuous music; Blake, whose weird designs are such a contrast to the sharp classical figures over which Mr. Swinburne loves to throw a new glow.” Despite Swinburne’s lack of moral principles, the reviewer finds A Critical Essay redeemed by Swinburne’s literary excellences.

Of this book we wish to speak in high praise; it shows a subtle power of analyzing character, a faultless style. Accept the ‘data,’ and it is a perfect work. If we could only take of it and Mr. Swinburne in general the view which dear old Charles Lamb takes of the Caroline Dramatists—that they belong to an airy world in which our ordinary moral rules have no place—we should be able to go further and pronounce it a valuable contribution to literary biography.As this is, however, not the case, the reviewer expresses “A doubt whether the author of Atalanta was quite the man to put the finishing touch to what poor Gilchrist left incomplete, and to draw out for us what lessons can be drawn out from the life of William Blake, painter and poet.” The Round Table shares this doubt and much more. Swinburne’s style is pronounced “too florid to be faultless,” and as for what the Imperial calls “the vagaries which all regret, but which cannot destroy his excellence,” The Round Table objects:

Vagary is a somewhat mild term to that mental and moral depravity in which Mr. Swinburne glories—the worship of license, the apotheosis of lust, which he would make the guiding rule of life . . . . A poet who fails in art by choosing such subjects as art revolts at; a philosopher who, less wise than Lord Lytton, dissevers the Good from the Beautiful; a moralist whose code of perfection is completed by a world made one vast brothel, can, it seems to us, be called excellent only by a curious twist of language.Of William Blake, painter and poet, The Round Table has nothing to say.

On 1 March 1868 “Mr. Swinburne’s Essay on Blake” was the subject of an article in The Spectator, one which was both longer—close to three thousand words—and more interesting than most. Though it displays a remarkable sense of Swinburne’s strengths and weaknesses, the view of Blake is the conventional one: “ . . . He has written a few little poems that will last as long as English literature . . . through all his poems there are distributed—at rare intervals,—lines of wonderful beauty and marvellous power, but it is also true that nine out of ten of his poetical compositions are fuller of deformity than of beauty, overloaded with chaotic rubbish, smoky with confused and laboring thought, disfigured by windy and grandiloquent nonsense, choked with unmeaning names, with an insane mythology, and an anarchic philosophy.” So far this is the usual Philistine rhetoric, but the reviewer does have an interesting critical point to make, one which may remind us of more recent attacks on Blake and on the Romantic tradition such as those of Yvor Winters and W. K. Wimsatt. “ . . . His poetry . . . habitually uses things which, as real things, have necessarily a dozen different attributes and accidents, in the place of some one of those attributes or accidents, and that one so often so arbitrarily chosen, and so frequently varied, that even his profoundest admirers, like Mr. Swinburne, are generally compelled to confess that it is pure haphazard to guess at the exact purport of Blake’s wild myths and dim allegories.” In the century that has passed since this was written, we have learned how to read Blake; but we must remember that Swinburne himself had not claimed that the long poems were consistent, successful, or even understandable—not until the Ellis-Yeats Works of 1893 was an attempt made to do this. The Spectator critic accurately describes a general problem in the interpretation of Blake but mistakenly assumes that the problem cannot be solved. He is also, with Conway, one of the few contemporaries to appreciate the value of the first color facsimile plates of Blake ever published. Finally, he takes care to discriminate between author and subject, attempting to do justice to both: ↤ 12 This interpretation is evidently the critic’s, for Swinburne does not mention Bacon, Newton, and Locke in his discussion of this design (plate 70 of Jerusalem) on page 293. The facsimile plate is the frontispiece to William Blake. Of course the three names appear in line 15 of this plate.

On the whole, this volume is a real addition to the knowledge of Blake’s great genius as an artist. Some of the illustrations—particularly the tender and sweet fancy taken from the book of Thel, of the marriage of the dewdrop and the raindrop, and the strange frontispiece in which the crescent moon, like the mystic eye of God, looks down on Blake’s three great enemies, the representatives of inductive reason (Bacon, Newton, and Locke)12, with a weird expression of intellectual scorn and penetrating insight—will fascinate even those who prefer a more intelligible style of art. Mr. Swinburne—though, with something of the feeling of a discoverer, he attaches far more importance than it deserves to Blake’s prophetic rhodomontade,—has profoundly studied his subject. Impertinent and shallow though he often is,—though he too often manages to cast a sense of impurity on Blake which Blake would never produce for himself,—he yet interprets Blake subtly on the whole, and with more of a sincere disinterestedness begin page 37 | ↑ back to top of admiration, than he has hitherto bestowed in print on any other poet.

The Westminster Review for April 1868 (pp. 587-88) makes the refreshing admission that “not having read Mr. Gilchrist’s Life of Blake, nor the poems of Blake, to which Mr. Swinburne constantly refers, we are for these, if for no other reasons, incompetent to give anything like a complete or final verdict.” This omission does not prevent the reviewer from asserting that Blake wrote some beautiful lyrics—he is favorably compared with Keats and Shelley—but that his other compositions are “doggerel rhapsodies” which bear out Allan Cunningham’s view that Blake “was subject to constant hallucinations.” Blake’s ideas were in his own case pure, but “with all allowance for poetical anticipation, the antinomianism of Blake is dangerous and his mysticism heretical, partial, and disintegrating.” The reviewer then passes from Blake’s disintegrating mysticism to the Life and Letters of Fred K. W. Robertson, M. A., Incumbent of Trinity Chapel, Brighton.

The last review to be considered was by an anonymous writer who had read Blake and read him sympathetically. It appeared in The Broadway annual (London and New York) for 1868, pp. 723-30. The critic recommends the Gilchrist Life to those “who would learn more about a very remarkable—and despite his peculiarities—a very loveable man,” and he refutes the charge of insanity. “Blake, though eccentric, was by no means mad, for he knew that his visions were not matters of fact, but phenomena seen by his imagination, nor did he expect other people to see what he saw. Insane persons, on the contrary, believe in the literal existence of their visionary fancies.” And he perceptively points out that the very publication of Swinburne’s book has significance: “The star of a hitherto neglected genius must be in the ascendant when the most distinguished of our youthful poets devotes a volume of 300 pages to a careful analysis of his various compositions.” The Broadway is also unusual in recognizing, with Swinburne, the inter-dependence of Blake’s text and his designs. “The only proper way to study these ‘Prophecies’ is in the original copies, where Blake’s flowingly-engraved words are aided by his wondrously fanciful and suggestive designs. Separated from these designs, the letter-press loses more than half its fervency and strength.” The last part of the review is addressed particularly to American readers, who are told that “Had Joseph Smith, the Mormon prophet, set his eyes on these writings, he would assuredly have adopted them as the sacred canon of his new revelation. . . . ” The “Visions of America” [sic] is discussed, and there follows an interesting parallel: ↤ 13 Swinburne had compared Blake and Whitman at the end of A Critical Essay (p. 303). On 17 February 1868 Whitman wrote to Conway “I have not yet seen the February fortnightly—nor the book William Blake—but shall procure & read both. I feel prepared in advance to render my cordial and admirant respect to Mr. Swinburne—& would be glad to have him know that I thank him heartily for the mention which, I understand, he has made of me in the Blake” (from facsimile in Moncure D. Conway, Autobiography [Boston and New York, 1904], I, between pp. 218 and 219).

Finally, let us observe two points in which this remarkable triumvirate of lyrists, Blake, Whitman,13 and Swinburne, all agree. They are all insurgents against the commonly-recognized dogmas of religion and social life; and they are all diligent Bible-students. Blake writes like a modern Ezekiel; Whitman, though his language is more nineteenth-century and vernacular, is suffused with Biblical influences; while in Mr. Swinburne’s essay, Biblical metaphors and turns of expression may be found in almost every page.The Broadway’s critic thus joins Conway in anticipating some modern trends in the understanding of Blake and his tradition, trends which have their origin in Swinburne’s Critical Essay.