Reviews

Cary Nelson. The Incarnate Word: Literature as Verbal Space. Urbana: Univ. of Illinois Press, 1973. $10.

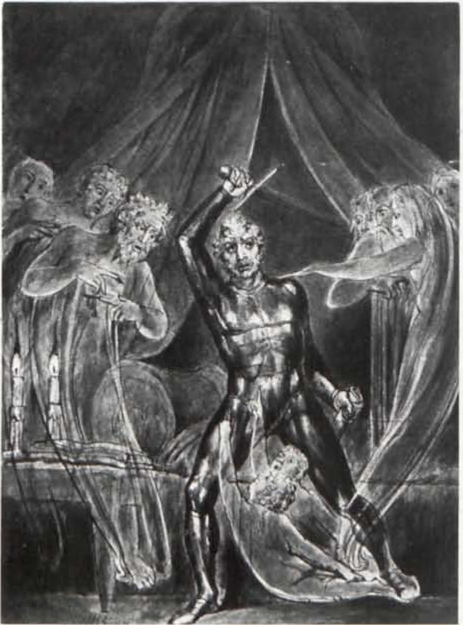

This book challenges the conventional or complacent pose of the reviewer who would like to present his response in the guise of statements “about” the book. In this case, whether it is a trivial or an important book, whether it is good or bad, depends almost entirely on how it is read. The main problem area in responding and evaluating turns on the persistent way in which everything Nelson says is self-descriptive. In his responses to the authors he reads, he is acting out or presenting to us a mode of consciousness which is precisely what he claims to “see” in the works discussed. For Nelson, the reader “performs an act of literature,” entering a “process in which the self of the reader is transformed by an external structure.” But such transformations can work either way, and I propose to look at Nelson as Blake looked at his Reactor, “til he be revealed in his system.”

In his chapter on Blake, for example, he begins by asserting tenets ascribed to “Freudian psychology” which sees “the artist projecting womb-receptacles appropriate to his psyche.” He quotes Williams with approval: “We express ourselves there, as we might on the whole body of the various female could

we ever gain access to her.” It seems appropriate, given this position, that all Nelson can see in Blake is a “womblike iconography,” which confirms that “Blake’s poetic world is an egg which the imagination fertilizes.” Thus Nelson’s performance of an “act of literature” on Blake resembles a rape where consent—the rapist’s only defense—has been established in advance. For him, Blake has “made the word flesh,” and “The most frequent feature of the illuminated books . . . is flesh—the human body.”Since for Nelson all activity, psychic or physical, is sexual, we can see the fruits of his critical endeavor as a series of interpretive “apocalyptic orgasms” in which “Each page is a revolution in consciousness that resurrects the imagination in a new body.” In his chapter on Burroughs the point is repeated in somewhat escalated form: “The whole of this mythology is initiated and fulfilled on every page of Burroughs’ work—in each moment of intersection between reader and text.” What Nelson apparently does not see is that when Burroughs says, “Gentle reader, we see God . . . in the flash bulb of orgasm,” his vision includes and is disgusted by Nelson’s response to it. For Burroughs this vision of God does not save us; it confirms our fallen state; it is what we must first begin page 109 | ↑ back to top acknowledge as our own, then somehow go beyond. When Burroughs says “Word is flesh” or “Your bodies I have written,” he is disgusted by the inevitability with which the sexual metaphor in its debased form absorbs all human experience. “The human organism is literally consisting of two halves from the beginning word and all human sex is this unsanitary arrangement whereby two entities attempt to occupy the same three-dimensional coordinate points.” Clearly then Nelson is acting out Burroughs’ system; but is he doing it in Burroughs’ sense and with his goal, to see “sex words exploded to empty space”? Or is he an example of what Burroughs means by addiction, someone who can’t break the habit? Is Nelson’s book parody or satire, a knowing reductio ad absurdum, an example for us to shun? Or is he himself seduced and luring us into the same seduction? In Blake’s terms, Nelson seems to be caught in the “Sexual Machine” (Jerusalem 39 [44]:25). He is not giving us the answer to Blake’s question: “ . . . what may Woman be? / To have power over Man from Cradle to corruptible Grave.” He is an unknowing example of what Blake meant by that power.

The important question lurking under all this concerns the possibility of conceiving and pursuing our redemption. Can we be saved by sex? And if so, in what way and on what level is sexuality the pattern of our redemption? Is the path from the beautiful woman to the Idea of The Beautiful a true path or an unconscious rationalization for sexual appetite—or is it the opposite misconception, a leading away from the primal reality of the flesh? These are questions Crane asks and answers in the “Three Songs” section of his Bridge. He suggests that it is impossible to achieve a spiritual vision of unity based on the pattern of the sexual act; but it is also impossible to avoid the trap:

Yet, to the empty trapeze of your flesh,If Crane is right, the apocalyptic model Nelson offers us is a circular trap, a revolving door that returns us to our predicament with precisely that degree of energy which informs our attempts to escape through the door. Lest this seem too fanciful, we can see Nelson himself going through the motions in his essay on Williams. First, he establishes that “white blankness is the space of the page we structure verbally.” Action in this space is the by now familiar verbal/sexual act. “The line propels us through the period, a black doorway into the whiteness of the page within which the line acts. Speech becomes an enactment of silence.” We go through the black doorway of the period only to return to the blank page, which we fill with more masculine words. How are these words now the “enactment of silence”? Discussing another period in Williams’ Paterson, Nelson informs us “That dot acts as a hole through which we fall. . . . The leap and fall through blank space and the measured pacing into emptiness are both related and different. . . . A period is immense; yet it is the waste of absolute finitude .” Nelson’s own period, at the end of this paradoxical prose, is wittily put a space beyond the final word in the sentence, a point beyond finitude. Presumably, we should get the point, and exit through that door into another space or emptiness. And Nelson does not waste his sonorous phrase. He uses it later where we begin page 110 | ↑ back to top learn that “To plant a field is to extend intimate space to the horizon, infinitely. A uniform and horizontal space, composed of inseparable clumps of handled earth. It never ends. Yet it is the waste of absolute finitude.” We exit through that period only to return to the same blank page filled with words, to see Nelson swinging one more time on the empty trapeze of flesh. The book seemingly claims to have found the moment in each day that Satan cannot find, and to be multiplying it. It may however, like the sexual metaphor that is the basis for every image of relationship in the book, be grinding its monotonous way on towards no climax at all. We are offered the image of man-poet-reader-farmer spilling his seed on the field as the pattern of the ultimate economy of the cosmos. It may, however, be the image of Onan raised to the anagogic level.

O Magdalene, each comes back to die alone.

Then you, the burlesque of our lust—and faith,

Lug us back lifeward—bone by infant bone.

In his penultimate chapter Nelson points out accurately that for Burroughs “total communication becomes either grotesquely funny or grotesquely hideous.” Nelson seems drawn to Burroughs as the moth is drawn to the flame, and as I read this chapter I was overcome with anticipation; it seemed that the only way to end the book would be with some grotesque form of self-destruction, some final revelation of the satiric wit that had been tempting me, playing with me throughout all these chapters on the Pearl Poet, Shakespeare, Milton, Swift, Blake, Wordsworth, Williams and now Burroughs. I thought that surely this “confidence” would prove to be the Melvillean, or the Prufrockian borrowed from Dante waiting for the moment when “human voices wake us and we drown.” But at the final moment there is a rapid modulation of intensity, a move towards dissociation. Burroughs’ novels turn out not to be “vehicles of revelation,” but the same book continually written “to perfect an instrument of aggression.” Somehow the point of all this aggression is safely avoided, as it had been avoided earlier in the chapter on Swift. We go on to learn that “The final choice is always an image of all choices at once,” an example of what Blake meant by his “Equivocal Worlds” in which “Up & Down are Equivocal.”

Rather than leaving the book hanging at this point, I am tempted to take a second look and to ask in all seriousness if we can find a matrix for examining it which establishes an “Up & Down” axis. I am convinced that there is such a matrix, but that it can only be discovered by an examination of what the book leaves out. It is a book which overcomes obstacles by ignoring them, which avoids the struggle of Blake’s “Mental Fight” by adopting the mode of pure assertion. Lacking a sense of difficulty, it fails to engage with the authors discussed on the one fundamental level they all share—that it is hard to achieve the goal of a timeless, transcendent experience without leaving our human nature behind at one extreme, or parodying it in an illusory ideology at the other. Nelson is offering his readers the “White Junk” fix that so outrages and frustrates Burroughs, that Blake fought against with his “Minute Particulars,” that the author of the Pearl Poem embodied in the ravishing confusion of his central image. At the heart of his method is an ignorance of and willful ignoring of time, supported by the assertion that “pure spatiality is a condition toward which literature aspires.” But to ignore time is to miss out on “the Mercy of Eternity,” and to become ironically trapped in that we seek to avoid. It is our existence in time that wears away at all moments of vision, domesticating them, integrating them into our established and programmed associations, reducing them to what we have always known and tried to avoid. ↤ 1 Dylan Thomas, “Ballad of the Long-Legged Bait.”

Time is bearing another son.We may share the poet’s urge to kill time, but we cannot achieve the visionary goal by ignoring it.

Kill Time! She turns in her pain!

The oak is felled in the acorn

And the hawk in the egg kills the wren.1

One aspect of Nelson’s ignorance and ignoring can be clearly seen in his chapter on Wordsworth. In it, he reduces the whole Prelude to a single posture or image, asserting that Wordsworth found and held firm that single timeless image he spent sixty years looking for, finding and losing. Nelson falls for Wordsworth’s wishful model of ascent, without ever realizing that the true subject of the poem is the experience of the fall, and the problem of coping with loss and the fear of future loss. What Nelson calls Wordsworth’s “apocalyptic posture” is the beginning of the problem, not its solution. He leaves the poets standing “On Etna’s summit, above the earth and sea, / Triumphant, winning from the invaded heavens / Thoughts without bound.” But at this point in the poem Wordsworth is sitting by his fire, indulging in “fancied images” (“bounteous images” in 1850), hoping that Coleridge has found what Wordsworth has been seeking, but knowing that “pastoral Arethuse” may “be in truth no more.” It may be “some other Spring, which by the name / Thou gratulatest, willingly deceived.” Innocence without experience, pastoral without context, is as Johnson observed “easy, vulgar, and therefore disgusting.” Of course in reacting that way to Lycidas Johnson was making the same mistake Nelson makes with Wordsworth, but with a different set of values. Whether or not we share Wordsworth’s hope that his Prelude was “all gratulant if rightly understood,” we miss the poem if we do not perceive and share in its ongoing struggle to avoid the poet’s fate in time, a beginning in gladness that ends in despondency and madness—a seeing by glimpses with a gnawing awareness that in times to come we may scarcely see at all.

Nelson quotes approvingly Wordsworth’s lines: “Anon I rose / As if on wings, and saw beneath me stretched / Vast prospect of the world which I had been / And was.” For Nelson this captures “a moment that spreads out autobiographical chronology like a map of time unfolded into space.” Yet how can we read these lines without recalling Eve’s account of her dream in Paradise Lost: “Forthwith up to the Clouds / With him I flew, and underneath beheld / The Earth outstretcht immense, begin page 111 | ↑ back to top a prospect wide / And various: wond’ring at my flight and change / To this high exaltation.” It is hard not to believe that we—like Wordsworth—avoid the danger implicit in such moments at our peril. For Nelson, “All fields are playing fields,” and he quotes with approval Freud’s lines: “A number of children . . . were romping about in a meadow. Suddenly they all grew wings, flew up, and were gone.” Is this the way it happens for the poets? Whoever those children are, wherever they go, how are we not to be left behind in Milton’s “fair field / of Enna, where Proserpin gath’ring flow’rs / Herself a fairer Flow’r by gloomy Dis / Was gather’d, which cost Ceres all that pain / To seek her through the world.” How can we ignore “all that pain” without being ignorant of it, and being ignorant of it how can we avoid being gathered by gloomy Dis? Plato poses the real problem and focus for the poets in his Phaedrus: “What we must understand is the reason why the soul’s wings fall from it, and are lost.” In Lear, Edgar may “save” Gloucester by tricking him, but that does not save those of us who see the trick. Mill may have been saved from despair by reading Wordsworth, as he reports in his autobiography. But his salvation was dependent on a selective blindness that prevented him from seeing that Wordsworth shared his own struggle with despair.

If by ignoring time, by ignoring difficulties and struggle, Nelson misses the point of Wordsworth and the other poets he discusses, he also misses an adequate context for literary interpretation. By insisting on space alone as the medium for vision he becomes an incarnation of the abstract model of the New Critic, committed to that “evasion of the whole problem of temporality” which Hartman so acutely isolates as the advantage and disadvantage of “The Sweet Science of Northrop Frye.”2↤ 2 Beyond Formalism (New Haven, 1970), pp. 33 ff. But unlike Frye, whose practice is “preferable to his theory,” Nelson’s approach stays at the distance of the middle ground, constantly invoking our immediate experience of literature yet never fully acknowledging that time is inseparable from our experience. Although he sets out to understand Swift’s Tale of a Tub “as reading experience,” he fails miserably because he hasn’t the faintest idea of the historical context in which that “reading experience” occurred and can still occur. This is obvious from his attempts to define satire by appealing to a norm of “efficient satire” which no satirist has ever shared—certainly not Swift, who in his “Apology” to the 1710 edition answers most of the problems that Nelson seems unable to cope with. But perhaps in his own way Nelson is close to the “reading experience” of the Tale, since like its first audience he fails to realize that the point of Swift’s satire is directed at a kind of Natural Religion of which Nelson is a twentieth-century embodiment. Swift was revolted by the empirical model of the mind constructing its universals and absolutes out of sense experience, but he carried the model in his own mind as we continue to carry it in our time.

This last observation touches on the most serious aspect of Nelson’s a-historical approach. By ignoring time, he ignores his own context, and the dangerous possibility that his brand of fleshy apocalypse is itself a byproduct of history. Camus saw in Feuerbach the birth of “a terrible form of optimism which we can still observe at work today and which seems to be the very antithesis of nihilist despair. But that is only in appearance. We must know Feuerbach’s final conclusion in this Theogony to perceive the profoundly nihilist derivation of his inflamed imagination. In effect, feuerbach affirms, in the face of Hegel, that man is only what he eats.”3↤ 3 The Rebel (New York, 1956), p. 146. The consequence of this form of deification can be seen clearly only if we can locate it as a process in a historical context. With a larger context, Camus would not have attributed the “birth” to Feuerbach, but might have traced it back to the seventeenth century. There is also a comical side to the lack of historical context as we realize that Nelson, 275 years later, is still anatomized in Swift’s description of “the noblest Branch of Modern Wit or Invention”:

What I mean, is that highly celebrated Talent among the Modern Wits, of deducing Similitudes, Allusions, and Applications, very Surprizing, Agreeable, and Apposite, from the Pudenda of either Sex, together with their proper Uses. . . . And altho’ this Vein hath bled so freely, and all Endeavours have been used in the Power of Human Breath, to dilate, extend, and keep it open: Like the Scythians, who had a Custom, and an Instrument, to blow up the Privities of their Mares, that they might yield the more Milk; Yet I am under an Apprehension, it is near growing dry, and past all Recovery; And that either some new Fonde of Wit should, if possible, be provided, or else that we must e’en be content with Repetition here, as well as upon all other Occasions. (“In Praise of Digression”)N. O. Brown claims that “The return to symbolism, the rediscovery that everything is symbolic . . . a penis in every convex object and a vagina in every concave one—is psychoanalysis.”4↤ 4 Love’s Body (New York, 1966), p. 191. Nelson would seem to agree, and to extend the “return” or “Repetition” to include all literature and interpretation as well.

There is another significant lack in Nelson’s book which seems related to the absence of a sense of struggle, and of historical context. Although the book is riddled with paradoxes—or the same paradox repeated endlessly—the repetitions are like literary fireworks that flash and explode and leave behind only clouds of smoke that offend the nostrils. There is no sense here of the profound mystery that underlies the mythical vision of incarnation as part of the pattern of redemption. John tells us that “That which is born of the flesh begin page 112 | ↑ back to top

is flesh; and that which is born of the Spirit is spirit.” Redemptive vision, as Blake knew, is the capacity to unite the two and to see the “Divine Revelation in the Litteral expression.” As Boehme points out, in his work on Nelson’s subject, this is a serious matter:Our life is as a fire dampened, or as a fire shut up in stone. Dear children, it must blaze, and not remain smouldering, smothered. Historical faith is mouldy matter—it must be set on fire: the soul must break out of the reasoning of this world into the life of Christ, into Christ’s flesh and blood; then it receives the fuel which makes it blaze. There must be seriousness; history reaches not Christ’s flesh and blood.Much of the seriousness in this matter is related to the fact that to enter the realm of “the incarnate word” is to enter a realm of metaphysical potency that was originally the exclusive prerogative of God. Elihu asserts that “the ear trieth words, as the mouth tasteth meat,” but he does so in a context in which Job must acknowledge that he utters “words without knowledge. . . . I uttered that I understood not.” If man lacks the power to utter “words that are things” as Byron longed to do, his speech can be knowledge only if it is congruent with something outside itself and more real than it is.

(De Incarnatione Verbi, II, viii, 1.)

To speak a word that can be eaten, a word that nourishes, sustains, fulfills, an “incarnate word,” is indeed a godlike act. To attempt it is a tremendous gesture full of risk, and to eat the word, to risk trusting it is the most dangerous of spiritually artistic ventures. It is to eat the forbidden fruit and risk the lot of eternal despair if one fails. “My word I poured. But was it cognate, scored / Of that tribunal monarch of the air / Whose thigh embronzes earth, strikes crystal Word / In wounds pledged once to hope—cleft to despair?”5↤ 5 Hart Crane, “The Broken Tower.” Poets have clearly longed through the ages for the godlike power of genetic utterance, or the lesser power of uttering a congruent word. In this context, as Touchstone says, “the truest poetry is the most feigning,” and “feigning” inevitably evokes the deepest level of desire (of faining) and the possibility of deception. The urge in poets is perhaps at bottom not all that different from the urge towards magic, the desire to find some words by which man can in some way touch and control the core of reality. It is clear that the magician has often been able to fool others, even at times himself. What is not so clear is whether he has ever succeeded in uttering the magical incantation that actually causes the effects he would fain achieve. Nelson’s book is an “incantation” in the full etymological sense; it is an incantation of incarnation. Like Audrey, we want somehow to know “is it honest in deed and word? is it a true thing?” Can we try his words as the mouth tasteth meat?

Our final glimpse of Satan in Paradise Lost is of him and his cohorts in a state of aggravated penance, greedily plucking the “Fruitage fair to sight” which was “like that / Which grew in Paradise.” But under the semblance, there is no substance; instead of fruit there are “bitter Ashes,” and an eternity of falling “Into the same illusion.” Nelson is oblivious to the danger that his fruit may turn to ashes when plucked. In some ways this is an enviable oblivion, but it is certainly not one shared by the poets he discusses. His book leaves us, like the tramps in Crane’s Bridge, still hungry after the Twentieth-Century Limited roars by with its slogans about Science, Commerce and the Holy Ghost.

But man must eat to live, and will be what he eats. Kafka’s Hunger Artist tries to make an art out of not eating, only to confess as he dies that he had to fast because he couldn’t find the food that he liked—that, if he had found it, he would have stuffed himself like everybody else. Roheim has claimed that schizophrenia is “food trouble,” that “There is only one story—that somebody was starved. But not really—only inside, in my stomach.” So to avoid starving we eat, and as eating is the active form of the fall, it must be the active form of redemption in the Eucharist, the thankful feast. We are what we eat; but what do we eat, and how do we eat it? In the first Night of The Four Zoas we encounter a feast: “The Earth spread forth her table wide. The Night a silver cup / Fill’d with the wine of anguish begin page 113 | ↑ back to top waited at the golden feast / But the bright Sun was not as yet. . . . ” At the feast “They eat the fleshy bread, they drank the nervous wine.” But in spite of the semblance, they are not eating the body of Christ. They are eating the fallen body of the natural world, eating it with their fallen senses and becoming what they behold.

It is no accident that Freud’s myth of the fall in Totem and Taboo locates the origin of man’s psychic disturbance in a primal cannibalistic feast. Nor is it accidental that for most psychologists the origins of the components of man’s psyche, like the origins of his body, can be seen in a process variously described as “internalization” or “identification and incorporation” or “ingestion” or “introjection” of the father and mother who thereby become “figures” or patterns of expectation and possibility that shape our potential for experience. If the process of individuation is to happen without alienation, there must be the development of “personal ‘realities’ which incorporate paradoxical discontinuities of the personal from maternal or parental realities.”6↤ 6 John S. Kafka, “Ambiguity for Individuation,” Arch gen Psychiat, 25 (Sept. 1971), 238. In a healthy process of growth a nourishment is provided and received which allows for an organic growth and individuation. But in a pathogenic process individuation is not achieved, and after the fact our fantasy organizes the experience as one in which by devouring the parents we have been devoured by them; we learn too late that we have become hooked like the addicts to the “White Junk” in Burroughs’ system. ↤ 7 Norman Mailer, Advertisements for Myself (New York, 1960), p. 310.

What characterizes almost every psychopath and part-psychopath is that they are trying to create a new nervous system for themselves. Generally we are obliged to act with a nervous system which has been formed from infancy, and which carries in the style of its circuits the very contradictions of our parents and our early milieu. Therefore, we are obliged, most of us, to meet the tempo of the present and the future with reflexes and rhythms which come from the past. It is not only the “dead weight of the institutions of the past” but indeed the inefficient and often antiquated nervous circuits of the past which strangle our potentiality for responding to new possibilities which might be exciting for our individual growth.7Blake makes the point more succinctly than either Mailer or Marx, when he asserts that Swedenborg has given us “Only the Contents or Index of already published books.” Nelson, like Swedenborg, is “the Angel sitting at the tomb: his writings are the linen clothes folded up. Now is the dominion of Edom.” Esau is called Edom, after the red pottage for which he sold Jacob his birthright. Under the dominion of Edom we find again the need for the feast of Ezekiel: “I then asked Ezekiel. why he eat dung, & lay so long on his right and left side? he answered. The desire of raising other men into a perception of the infinite.” The same desire moved Swift in his time, Blake in his, and Burroughs in ours. Like Ezekiel, Burroughs holds a parodic mirror up to our diet and throws us the same challenge: “We Are All Shit Eaters. . . . ” Nelson finds the message “inexplicable and intolerable,” misses the shock of recognition which might provide the point for a new beginning, and ends his book with a chapter called “Fields: the body as a text.” This final section is a montage of quotations and assertions organized around various themes, and is strongly reminiscent of N.O. Brown’s Love’s Body. Earlier in the book Nelson has suggested that Brown’s work and Whitman’s “symbolically offer us the visionary body of their author,” and it seems clear that he is making the same gesture or offering with his Incarnate Word. The emphasis here is crucial, and goes beyond the ordinary sense in which we can imagine any book to be an offering by its author. This is an invitation self-consciously modeled after Christ’s invitation to his disciples, an invitation to a communion with the promise of redemption if we take and eat. In fact, however, it is the gift of Comus, “Off’ring to every weary Traveller / His orient liquor in a Crystal Glass.” The “misery” of the band that follows Comus is so “perfect” that they cannot “perceive their foul disfigurement, / But boast themselves more comely than before.” I can only hope that Nelson does not gather a similar band around himself.

I once heard of a university class which had been reading Love’s Body as a text. In the final meeting of the class, the students tore pieces from the book and ate them, then burned the remainder and marked their foreheads with ashes from the charred remains. I was moved by a sense of the depth of their hunger, and the archetypal level of their response to it. And I often wonder how they felt as they returned from the field after class to eat their lunch in the cafeteria. I wonder if Nelson, like them, may not be an incarnation of Kafka’s panther, the missing half of the puzzle:

. . . and they buried the hunger artist, straw and all. Into the cage they put a young panther. Even the most insensitive felt it refreshing to see this wild creature leaping around the cage that had so long been dreary. The panther was all right. The food he liked was brought him without hesitation by the attendants; he seemed not even to miss his freedom; his noble body, furnished almost to the bursting point with all that it needed, seemed to carry freedom around with it too; somewhere in his jaws it seemed to lurk; and the joy of life streamed with such ardent passion from his throat that for the onlookers it was not easy to stand the shock of it. But they braced themselves, crowded round the cage, and did not want ever to move away.