article

begin page 7 | ↑ back to topBlake’s Visions of the Last Judgment: Some Problems in Interpretation

Unaccustomed as I am to presiding over Last Judgments, I have no intention of playing the Messiah at this one. The following are some questions, problems, and a few hypotheses which I hope will stimulate discussion of Blake’s pictures of the Last Judgment, and indicate directions for further investigation.

I. What did Blake mean by “A Vision of the Last Judgment”?

Perhaps we should begin by asking what he meant by a Vision, distinguishing it from such things as hallucination, vivid visual memory, or Platonic “form.” What is the ontological status of a Vision? How can Blake claim that it reveals “Permanent Realities” (E545) at the same time he admits that “to different People it appears differently” (E544)? Can we arrive at a psychological definition that will correspond with Blake’s literary definition (“The Last Judgment is not Fable or Allegory but Vision . . . Allegory & Vision ought to be known as Two Distinct Things” E544)? Is it sufficient to explain this distinction by referring it to the distinction between imagination and memory? (“Fable or Allegory is Formd by the daughters of Memory. Imagination is Surrounded by the daughters of Inspiration.”) Are memory, allegory, and fable simple antitheses of inspiration, vision, and imagination, or are they constituents of these “higher” mental and literary processes?

What is the temporal significance of the word “Last”? Does it mean “last in time,” the final event of history? Or does it mean something like “utmost” or “ultimate,” denoting an event of peak intensity and significance (like the epiphanic “Moments” described in Milton), rather than temporal finality? What happens after a (or the) Last Judgment? Is it a collective or individual experience, or both? Is Blake’s notion of the Last Judgment completely or only partially a-historical?

What is the significance of the word “Judgment”? In particular, what are the implicit norms, values, or moral standards behind Blake’s vision of Judgment? How can we reconcile his division of mankind into Just and Wicked, Sheep and Goats in both his verbal and pictorial treatments of the Last Judgment with his satires on categories of good and evil in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, and his notion of the apocalypse as Universal Forgiveness in Jerusalem? Is Blake being blithely inconsistent or consciously ironic and paradoxical when he provides the following definition of a Last Judgment: “The Last Judgment when all those are Cast away who trouble Religion with Questions concerning Good & Evil” (E544)? Doesn’t Blake simply re-introduce new categories of good and evil (the good are those who don’t raise questions concerning good and evil; the evil are the “troublesome questioners”)? Who or what is “cast away” in a Last Judgment? Psychological “States” or “Individuals”? Who or what is “saved”? What does it mean to be saved in Blake’s Last Judgment?

II. How are Blake’s ideas about the Last Judgment expressed pictorially?

We can wrangle over the preceding questions by referring to Blake’s writings, but the really interesting problem, in my view, is to encounter his pictures of the Last Judgment on their own terms. If we did not know these pictures had been created by William Blake, the radical, unorthodox visionary, would we be so likely to suspect that they depart from Christian doctrine, or express unorthodox notions of the Last Judgment? Suppose an orthodox Christian were to look at these pictures and tell us, “I don’t care what you say Blake intended in these designs; what he accomplished was a very traditional image of the Last Judgment as I understand it. The Messiah is in heaven, surrounded by his elders, apostles, and angels; the saved are ascending to heaven on his right hand, the damned are falling into hell on his left. You may claim that they are ‘States’ (whatever that is) but Blake drew them as human forms. If Blake was trying to subvert my orthodox picture of the Last Judgment as the time when the Lord separates good people from bad, he certainly failed to do so; in fact, he just confirms it!” (My apologies to orthodox Christians for this caricature.)

Albert S. Roe, in his ground-breaking study of Blake’s Last Judgment pictures, argues that “it is important to remember that Blake had no belief in any eternal damnation of the individual,” and that it is only the casting out of mental “error” that he represented in his Last Judgment drawings. (Roe’s essay first appeared in HLQ in 1957; it is reprinted in The Visionary Hand, ed. Robert Essick, Los Angeles, 1973, pp. 201-32.) I want to agree with this statement (although I suspect that Blake means something different by “eternal” from what Roe means here); the problem is, do the pictures make this statement in pictorial terms? Are there any pictorial clues to tell us that the human figures are not “really” human beings, but representations of mental states? And what about the larger question of the relation of Blake’s pictures to tradition? The symmetrical structure of saved and damned has been part of Last Judgment iconography since the earliest days of Christian art; André Grabar (Christian Iconography, Princeton, 1968) traces the theme ultimately to images of Manichean propaganda circulated around begin page 8 | ↑ back to top 240 to 270 A.D. It is hardly surprising that an implacable moral dualism pervades the tradition. The question is, did Blake simply accept and imitate this dualism (hence, the conventional symmetry of his designs) or did he find some way of modifying and transforming it in his pictures of the Last Judgment? To answer this question we need to investigate, not just Blake’s intentions, but the pictorial tradition within which he was working.

III. How do Blake’s treatments of the Last Judgment adopt, modify, or transform the pictorial conventions associated with this theme?

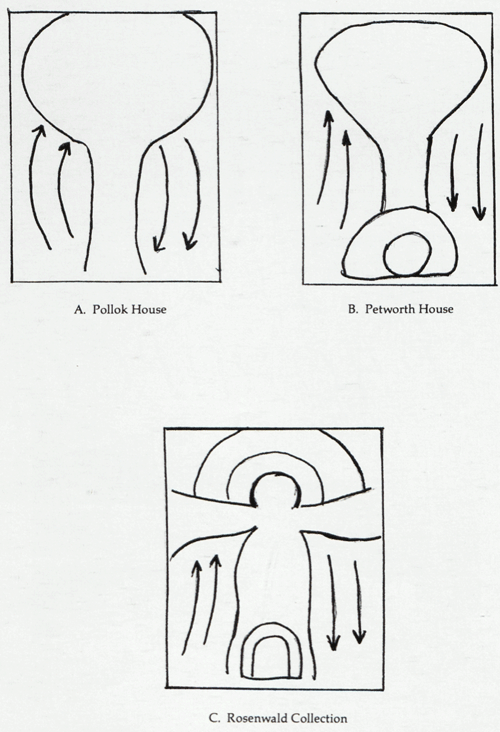

A. S. Roe argues that “traditional literary and artistic sources” do not have much bearing on Blake’s treatment of the Last Judgment: “With another artist, this might very well constitute the major interest of such a study as this, but with Blake, even when treating a theme involving so many traditional connotations as the Last Judgment, his approach to it is essentially personal” (205). And yet, when Roe sets about defining the “personal” quality of Blake’s compositions, he appeals to a modification of the tradition, suggesting that the position of Christ’s hands in Blake’s drawings (resting on the book in the Pollok House version, on the scroll in the Petworth copy, outstretched in the Rosenwald drawing) departs from “medieval tradition, where He either holds His hands down by His sides with palms outward to display His wounds, or else holds His right hand raised in blessing while His left is lowered in a gesture of judgment on the damned” (208). Roe’s interpretive tactics seem to me superior to his overall strategy of minimizing tradition; in fact it is only the knowledge of tradition that allows us to gauge the personal modifications Blake introduced. The question is, what other aspects of Blake’s treatment of the Last Judgment disclose departures from pictorial traditions? This is obviously a larger topic than we can handle in a few hours, but it might be helpful to sketch out some possible lines of investigation.

The first problem is to determine what pictorial renditions of the Last Judgment Blake might have known, either first hand or through engravings. Aside from the certainty that he knew Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel fresco through engravings, and the high probability that he knew Dürer’s series of Apocalypse engravings, it is surprising how little is known about this matter. Did the keen interest in the Italian primitives among late eighteenth century connoisseurs (documented by Rosenblum and Irwin) extend to their frescos of the Last Judgment? Could Blake have seen engravings after Last Judgments by Giotto or Fra Angelico? Or, for that matter, could he have seen some indigenous English treatments of the theme depicted, as Samuel Chew tells us (The Pilgrimage of Life, Yale, 1962, 257-58) “on the west wall of many church naves”? Could Blake have seen the de Quincey Apocalypse in Lambeth Palace? What other treatments of the theme in illuminated manuscripts, stained glass, or sculpture would have been available to him?

Until we have answered these sorts of questions it will be very difficult to substantiate any claims about transformations that Blake might have been making, and our sense of what is “personal” in his pictorial treatment of the Last Judgment will be largely hypothetical. In the hope of stimulating refutation or confirmation, however, let me advance the following sub-questions and hypotheses:

1. Whatever medieval treatments of the Last Judgment Blake knew, they would probably conform to the general style found in Anglo-Norman manuscripts, which divides the composition into compartments separated by linear boundaries. A common device was to divide the picture into three levels (the Messiah with angels, the saints, and mankind) separated by two horizontal lines. (This principle of separation, but not the groupings, persists in Michelangelo’s fresco—note the two bands of empty space which traverse his Last Judgment.) How does Blake respond to this highly structured treatment of the theme? What structural principles inform his compositions?

2. Emile Male suggests that the medieval artist understood the apocalypse as “a drama in five acts,” including preliminary signs, Christ’s appearance, the Resurrection of the Dead, the Judgment, and the Separation of the Sheep and the Goats. Treatments of the theme tended to focus on one of these acts, or perhaps to combine the last two. Doesn’t it seem that Blake is trying to pack all five acts into one image? The Last Judgment tends to attract an encyclopedic, comprehensive treatment, but Blake’s is by far the most encyclopedic I have seen (the angels with trumpets in the center are the “preliminary signs,” the Messiah is appearing in the clouds, the dead emerge from the ground at the bottom of the design, etc. The presence of the Whore of Babylon and the Seven-Headed Beast also suggest the inclusion of an even earlier phase in the apocalyptic drama, the so-called “Trial of Sin.”)

3. Is the absence of the Archangel Michael (often depicted just below the throne of Christ) a significant omission?

We also should try to gauge Blake’s response to his primary challenge, the Sistine Chapel fresco by Michelangelo. Although he could have known this design through at least ten different engravings, he was probably best acquainted with the version by Bonasone which was in the collection of George Cumberland. Blake’s chief debt to Michelangelo would seem to be the (no longer revolutionary) practice of filling his Last Judgment with nudes, and the general tendency of Late Renaissance masters (including the hated Rubens) to stress the dynamic, explosive possibilities of the theme, rather than (as in the Middle Ages) its distributive, judicial character. And yet A. S. Roe’s intuition that Blake’s treatment is medieval “in spirit and even in detail” (207) still seems compelling. Why? Does it have something to do with relative flatness and non-illusionistic quality of Blake’s design, coupled with the sense of presiding symmetry and controlled structure? Again, what is that structure?

begin page 9 | ↑ back to topAs a footnote to our discussion of Michelangelo’s influence on Blake I offer the following. In 1806, the year Blake composed his first known Last Judgment drawing (the Pollok House version), the first English life of Michelangelo was published, a life which was to dominate English understanding of Michelangelo for the next fifty years. This book includes a fold-out engraving by William Ottley of the Sistine Chapel fresco, and a commentary on the painting by the author, Richard Duppa, which is less than reverential towards the Divine Michelangelo. Duppa complains of his Last Judgment that “the indiscriminate application of one character of muscular form and proportion makes the whole rather an assemblage of academic figures, than a serious, well-studied, historical composition . . . . The mind is divided and distracted by the want of a great concentrating principle of effect” (The Life of Michel Angelo Buonarroti,[e] 2nd ed., London, 1807, 204-05). I have my doubts that Blake would have agreed with Duppa’s criticism. But it is interesting that his own Last Judgment pictures have precisely what Duppa says is missing in Michelangelo, a “great concentrating principle of effect.” At some point we should discuss what this principle is, but for now we can surely agree that there is some kind of structure or gestalt in Blake’s Last Judgments which makes the multitude of figures seem like parts of a larger pattern rather than an “assemblage.” Could not this sense of structural unity have been the thing that prompted Ozias Humphreys to praise the Petworth version for “grandeur of conception . . . and the sublimely multitudinous masses & groups which it exhibits,” and to rate Blake’s composition as “in many respects superior to the Last Judgment of Michael Angelo . . . . ”(see Blake Records, ed. G. E. Bentley, Jr., Oxford, 1969, 188-89)? Certainly it would be the overall structure and conception, not the individual figures, that would be noticed by a man on the verge of blindness, as Humphreys was when he wrote the above remarks. (One could argue, of course, that Humphreys’ blindness made him a very bad judge of anything concerning these pictures.)

Whatever new information we gather about Blake’s use of tradition, his response to the challenge of Michelangelo, his tranformations of medieval iconography[e] or structure, we will find, I suspect, that his Last Judgments are a creative synthesis of Renaissance and medieval elements. A more precise grasp of this synthesis will allow us to see more exactly the Vision of the Last Judgment that he managed to articulate in pictorial terms. In the meantime, it might be interesting for us to meditate on that “concentrating principle” of structure which keeps coming up as we try to analyze the effect of Blake’s Last Judgment pictures.

IV. What is the structural pattern or “concentrating principle of effect” in Blake’s Last Judgment pictures? How does it evolve in the various versions?

I offer below three schematic diagrams to clarify the structural skeletons of the Pollok House, Petworth House, and Rosenwald drawings. I do not believe, however, that geometric forms are intrinsic bearers of meaning in Blake’s art; on the contrary, it seems to me essential that these forms remain ambiguous. The question here is, what range of ambiguity is suggested by these forms? What is Blake trying to evoke? A concrete object or objects? A pattern of forces? An organ or organism? How does this structural pattern develop? Is there evidence of a direction, a teleology—or must we settle for the answer that Blake just wanted to try different ways of organizing it for no particular reason?

While we are on the question of formal development, we might consider another major question, the iconographic variations among the versions of the Last Judgment. What figures appear in every version? Which ones do not? What is the effect or significance of changes in position, perspective? David Erdman detects an increase in the number of human forms, a decrease in non-human forms in the sequence of drawings. In other ways (position of trumpeting angels, perspective around Christ) the latest version seems to return to the earliest. Can we guess what the lost tempera version (the climactic picture, presumably) looked like? What things described in the notebook draft of A Vision of the Last Judgment do not appear in the Rosenwald drawing?

If all these unanswered questions do not prove sufficiently irritating, perhaps the following summary hypothesis will stir debate. The key to Blake’s structural conception of the Last Judgment is his remark on the organization of the groups in the lost tempera: “when distant they appear as One Man but as you approach they appear Multitudes of Nations” (E546). The early versions of the Last Judgment are organized around a portion or organ of the human form—probably the skull—and the cyclic movement of the figures within that form represents the cycle of consciousness casting off error and embracing truth. The figures are, as Blake claimed, not “Persons” but mental “States” which exist inside persons. As Blake developed his notion of the “Human Form Divine” and the myth of a Universal Man (Albion) in his prophetic books, so also his concept of the Last Judgment as an event in the consciousness of this Universal Man began to develop, an event which can be seen at the individual, microcosmic level as “a” Last Judgment or epiphany, at the collective, macrocosmic level as “the” Last Judgment. The cyclical quality of his compositions, their mirror-like symmetry, the even-handed posture of the Messiah, the absence of the warrior angel Michael, all these features are Blake’s way of saying that the divisive, judgmental aspects of the Last Judgment have been subordinated to a Vision of the Last Judgment as a continuing process, a recurrent event in the life of consciousness, a moment of welcoming and awakening into the total life of the imagination.

I am not sure that this will convince the hypothetical “orthodox Christian” I invented earlier, but perhaps it will incite some Mental Warfare among us infidels.

begin page 10 | ↑ back to top