The Jerusalem Marathon

The Abbey at Sutton Courtenay, 6-7 November 2004

By Susanne Sklar

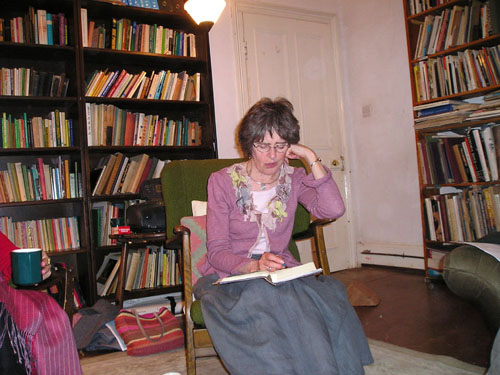

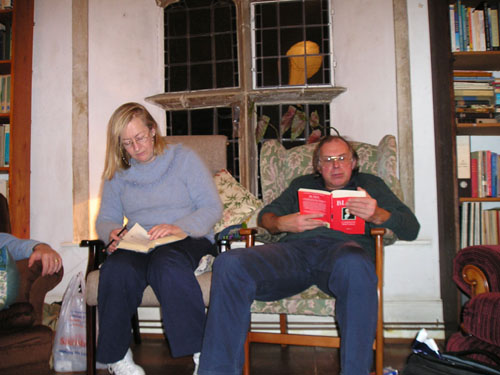

Queen's College, Oxford In the preface to Jerusalem Blake says he chooses the words in his poem to suit "the mouth of a true orator" (Jerusalem pl. 3). I think the poem is meant to be heard and seen. The Blake Society offered to endorse an overnight Jerusalem reading. My dissertation supervisor, Professor Christopher Rowland, agreed to be a "visionary form." I asked him to read Jesus. My friend Barbara Vellacott (reading Vala) arranged that we could give voice to Jerusalem in the library of the 13th century Abbey at Sutton Courtenay (about 15 miles from Oxford). Eleven people read in very comfortable armchairs and several commented upon the mullioned windows with their stained glass insets, caryatid angels supporting the ample mantlepiece, the warm fire, the tall bookcases. Philip Pullman, reading Albion, contributed good whisky to the event. Others brought biscuits, fruit, sparkling water, energy bars, strong coffee and tea. We knew this would be physically draining. We read the first three chapters of Jerusalem from just before 7 pm and on into the night. We divested ourselves of watches when Jerusalem began so we did not know how much after midnight it was when we walked through the dark gardens to the guest house. We seemed to be walking through the same doorways Los enters in the poem's frontispiece. Carrying torches, like Los' globe of light, we rose before dawn to begin chapter four. This was not a performance. There was no audience, no illusion of "aesthetic distance." No one rehearsed beforehand, though most participants knew which character they would read. Jerusalem has seven main speaking parts (Jesus, Albion, Jerusalem, Vala, Los, Enitharmon, and the Spectre) as well as many minor roles contained in its choruses of Sons, Daughters, and Eternals/Cathedrals. The text is more than 60% narration and we each became members of that narrative body, sometimes individually reading paragraphs or phrases, sometimes reading in unison, sometimes in counterpoint, especially when Israel gets mapped onto Britain. We echoed and whispered and shouted. Francis Gilbert, who embodied Eternals, observed that "we operated as One Body" when we each "passed the baton" of Blake to one another. Andrew Vernede, our Los, enjoyed the freedom to interrupt, to flow together; "we were borne up by voices," said Eleanor Lord, our Enitharmon, "like a choir." Philip Pullman (Albion) commented, "the flow of the poem was clarified and it came to life in Minute Particulars." Occasionally Blake's words whirled, making more sound than sense. Several readers commented on how dissonance and sense work together when the poem is heard. Chris Rowland (Jesus) said that "the words pile up, as in some liturgical event. Jerusalem is to be experienced. . . ." "Such a poem should be read collectively," said Tony Eaude, who embodied Albion's Sons. Tim Heath (the Spectre) was struck by Jerusalem's "clutter" and said that out of its clutter an image can clearly appear. He came away seeing that "there is a throne in every man . . . it is the throne of God." Each reader came away with different images. Jane Parkinson (the Cathedral Cities) was most struck by how Los' anvil tempers "the harmony and cacophony." Chris Rowland (Jesus) saw "the image of the child leading the old man through London." Tony (the Sons) saw naked heroes, distorted, battling implacable forces. The poem speaks to different readers in very different ways. It cannot be tidily interpreted. Francis Gilbert (Eternals), Barbara Vellacott (Vala), and I (Jerusalem) were particularly struck by the text's holisitic nature. As dawn filtered through the mullioned windows Francis noted that the many deaths, resurrections, and divisions came together in the Fourfold Vision. "I felt something like a resurrection in myself," he said, "and all the others made sense." I am in the second year of my theology D.Phil. at Queen's College. Guided by the goodness of Chris Rowland I have pored over Jerusalem's minute particulars. Blake's Eternals say: "Expanding we behold as One. . . ." Giving the text to eleven voices expands it. Now Jerusalem is an organism of imagery, a vast speaking picture. The movement of heard words is like a mobius strip of Blake design. The poem tells a story, yet everything in it is always happening. Vala's shuttles sing in the sky; I see the mundane egg, woven and forged, the daughters whipped, their fury, the anvil and Los; a cycle of violence, love in a Lily; Jesus always is. Beulah wings morph into black dragon wings which become seraphim flames of ruby and gold. The lake of fire is living water. Ulro, Beulah, and Eden always are; they are ways of perceiving. Altering perception is especially important back home in America, whose altars (in Jerusalem's words) now "run with blood" as "Euphrates is red with blood" (Jerusalem 79:53-69). The poem presents a choice. Moral Virtue and Life grow on very different trees. "The arts of life they changed into the arts of death" can be changed again to arts of life. Jerusalem is a poem whose time has come.

|