REVIEWS

ROMANTIC CONTEXT: POETRY

Significant Minor Poetry 1789-1830

Printed in photo-facsimile in 128 volumes

Selected and Arranged by Donald H. Reiman

The Garland Facsimiles of the Poetry of James Montgomery

James Montgomery. Prison Amusements and the Wanderer of Switzerland, Greenland and Abdallah, Verses to the Memory of the Late Richard Reynolds/The World Before the Flood, The Chimney Sweeper’s Friend.

If you were asked to name the significant minor writers of the Romantic period, you would probably think of Southey or Crabbe or even John Clare before James Montgomery. And yet, in his day Montgomery was known in England and America as a poet, essayist, and humanitarian. His popular Wanderer of Switzerland, a tribute to the fight against French tyranny, inspired Byron to claim that it was “worth a thousand ‘Lyrical Ballads’ and at least fifty ‘degraded epics.’”1↤ 1 See Byron’s notes to English Bards and Scotch Reviewers in Byron: Poetical Works, ed. Frederick Page, rev. ed. John Jump (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1970), p. 866. Although Byron’s enthusiasm was extravagant, the historical and social range of Montgomery’s work and his relationship to the major English Romantics make him interesting to modern critics.

The Garland Publishing Company’s five-volume facsimile edition allows us to view Montgomery’s works in their original form, with the poet’s prefaces and dedications, as well as with illustrations by contemporary engravers.2↤ 2 The volumes are part of a Garland Series, Significant Minor Poetry, 1789-1831, ed. Donald H. Reiman. All quotations from Montgomery’s poetry refer to this edition and will be cited by line or page. While British and American collections of Montgomery are available in most university libraries, the originals are rare. Furthermore, with facsimiles, we can appreciate the poems as books that, like the Songs of Innocence and of Experience and the Lyrical Ballads, were designed to have a certain impact on an audience.

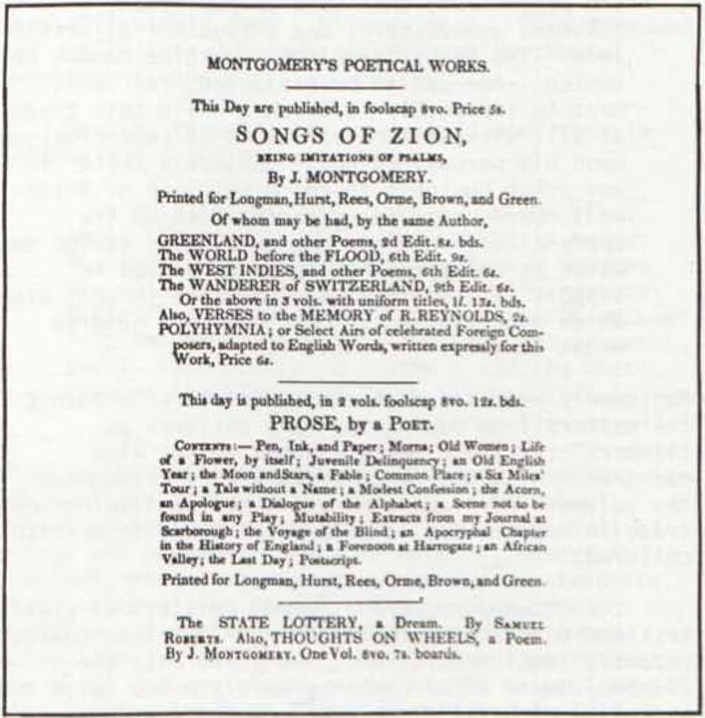

The Garland reproductions do not necessarily represent the poems that Montgomery thought to be his best and collected in his Poetical Works of James Montgomery (1836). Nor do the volumes include the works for which Montgomery is best remembered today, the Christian hymns and imitations of psalms.3↤ 3 The Greenland volume does contain some religious poems, but neither Montgomery’s Christian Psalmist nor his Songs of Zion is reprinted. They emphasize instead Montgomery’s relationship to the themes and commitments of the English Romantics: Prison Amusements are written when Montgomery is imprisoned for libel during the repressive 1790s; The Wanderer of Switzerland reflects disillusionment with the course of the French Revolution; The West Indies celebrates the abolition of the slave trade in England in 1807; and The World Before the Flood is Montgomery’s self-consciously Miltonic poem.

Donald H. Reiman’s editorial choices generally make sense from this perspective, although I wonder why the Verses to the Memory of the Late Richard Reynolds (1816) were reproduced with The World Before the Flood (1813), since the poems offer nothing but sincere praise for a pious Quaker from Bristol. Perhaps instead of these Verses, the series could have included Pelican Island (1827), Montgomery’s last long poem and his only venture in blank verse. Also, the facsimiles, necessarily without modern editorial comments, would be more useful with new, separate introductions covering the material in each volume, instead of Reiman’s general essay.4↤ 4 I depend on John Holland and James Everett’s seven-volume Memoirs of the Life and Writings of James Montgomery (London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, 1854) for Montgomery’s letters, speeches, and editorials, as well as for anecdotes, comments, and letters by others concerning Montgomery. I refer to this work by volume as Memoirs.

Montgomery was born in Scotland in 1771, the son of Moravian missionaries. When he was six years old, his parents left for the West Indies after placing him in the Moravian School at Fulneck near begin page 29 | ↑ back to top

Leeds. He excelled for a while, but became more dedicated to poetry than to the required curriculum. After leaving Fulneck, trying several jobs, and unsuccessfully peddling his poems in London, Montgomery was hired as a clerk on the Sheffield Register by the editor Joseph Gales. When Gales fled to America in 1794 under the threat of political imprisonment, Montgomery took over the paper, now the Sheffield Iris, and remained editor until 1825. During these years and until his death in 1854, Montgomery published several volumes of poetry, reviewed other poetry in the Eclectic Review, lectured on belles lettres and literary history in London, and participated in the workaday world of Sheffield.Such is the bare outline of Montgomery’s life. But Montgomery, like Wordsworth, would no doubt have directed us to look for his life in his works. The Garland facsimiles invite us to view the works chronologically from Prison Amusements in the 1790s through The Chimney Sweeper’s Friend and Climbing Boy’s Album, published in 1824 a year before his retirement from the Iris.

The first volume includes both Prison Amusements and The Wanderer of Switzerland, the former published in 1797 in London under the pseudonym Paul Positive as Prison Amusements, and Other Trifles: Principally written during Nine Months of Confinement in the Castle of York. Montgomery found himself in York Castle twice as a result of his position as editor at a time when charges of libel and sedition were regularly leveled. But Montgomery was not a Radical; the motto of the Iris read “Ours are the plans of fair, delightful Peace, / Unwarped by party rage, to live like brothers” (Memoirs, I, 175). Montgomery warned that the staff of the Iris “Have not scrupled to declare themselves friends to the cause of Peace and Reform, however such a declaration may be likely to expose them in the present times of alarm to obnoxious epithets and unjust and ungenerous reproaches. . . . they scorn the imputations which would represent every reformer as a Jacobin, and every advocate for peace as an enemy to his King and country” (Memoirs, I, 177).

Although Montgomery commented bravely on politics in the Iris, his Prison Amusements deal neither with the political climate nor with the events leading up to his imprisonment. They are simply about passing the time in prison. In the lyrics and verse epistles in the volume, Montgomery uses conventional imagery and allegorical plot structures featuring free-spirited robins and captive nightingales. Because his treatment of his situation is superficial and his allegorical pose suggests a distance incompatible with often inflated language, the poems remain trifles. Their occasion may be curious and revealing, but the texts are limp.

The Wanderer of Switzerland and other Poems, published in London and printed by Montgomery in 1806, has more life. Montgomery wrote The Wanderer in a ballad meter and structured it as a dialogue between a Swiss patriot forced to flee his homeland after the French invasion and a hospitable Shepherd living “beyond the frontiers.” The theme of natural liberty against political tyranny and what Daniel Parken of the Eclectic Review termed Montgomery’s “warmth of sentiment” (Memoirs, II, 84) attracted British readers. But even the sympathetic Parken noted that the metrical style and debate structure were monotonous in a long, six-part poem, and that Montgomery’s expression was not “brilliant” (Memoirs, II, 84). In the Edinburgh Review, Francis Jeffrey was typically less charitable, charging that “Mr. Montgomery has the merit of smooth versification, blameless morality, and a sort of sickly affectation of delicacy and fine feelings, which is apt to impose on the amiable part of the young and the illiterate” (Memoirs, II, 133).

Perhaps Montgomery himself best explains both the popularity of The Wanderer and its failings in a comment written years later: “the original plan of a dramatic narrative for a poem of any length beyond a ballad was radically wrong, and nothing perhaps but a little novelty (now gone by) and the peculiar interest of the subject—at once romantic and familiar to our earliest feelings and pre-possessions in favour of liberty, simplicity, the pastoral life, and the innocence of olden times—could have secured to such a piece any measure of popularity” (Memoirs, III, 221). The form of The Wanderer does seem wrong because the regularity of ballad rhythms is not complemented by a sparse,[e] fast-paced narrative of events—the style of the traditional folk ballad debates, of many of the Lyrical Ballads, and of Montgomery’s own “Vigil of St. Mark.” begin page 30 | ↑ back to top Furthermore, despite the debate structure, the poem lacks dramatic development.

In “The Vigil of St. Mark” (published with The Wanderer, pp. 137-46) Montgomery fuses ballad rhythms with structural compression. This poem is based on a legend, which Keats used in his fragmentary “Eve of St. Mark,” that on this eve the ghosts of all the people who will die in the coming year walk in a gloomy procession. In Montgomery’s poem, a nobleman named Edmund sees his love Ella in such a procession while he is away from home; he arrives home to discover Ella’s funeral procession, a scene described in eerie flashes of action and a quick rhythm:

‘Twas evening: all the air was balm,The poem then concludes with a vision of Edmund walking with Ella’s ghost on each eve of St. Mark. Montgomery compresses the narrative but suggests action by showing the result of events, their emotional impact.

The heavens serenely clear;

When the soft magic of a psalm

Came pensive o’er his ear.

Then sunk his heart; a strange surmise

Made all his blood run cold:

He flew,—a funeral met his eyes;

He paused,—a death-bell roll’d.

There are other good poems in the volume, such as “The Common Lot,” but many of the pieces share the same weakness: Montgomery presents a situation as allegorical or metaphorical and then explains it, making it so fixed and brittle that it loses whatever imaginative freedom it had. In “The Snow-Drop” (pp. 154-60), for example, the narrator discovers a snowdrop on a walk and welcomes it as a harbinger of spring. But then the power of the metaphor is explained away:

There is a Winter in my soul,

The Winter of despair;

O when shall Spring its rage controul?

When shall the SNOW-DROP blossom there?

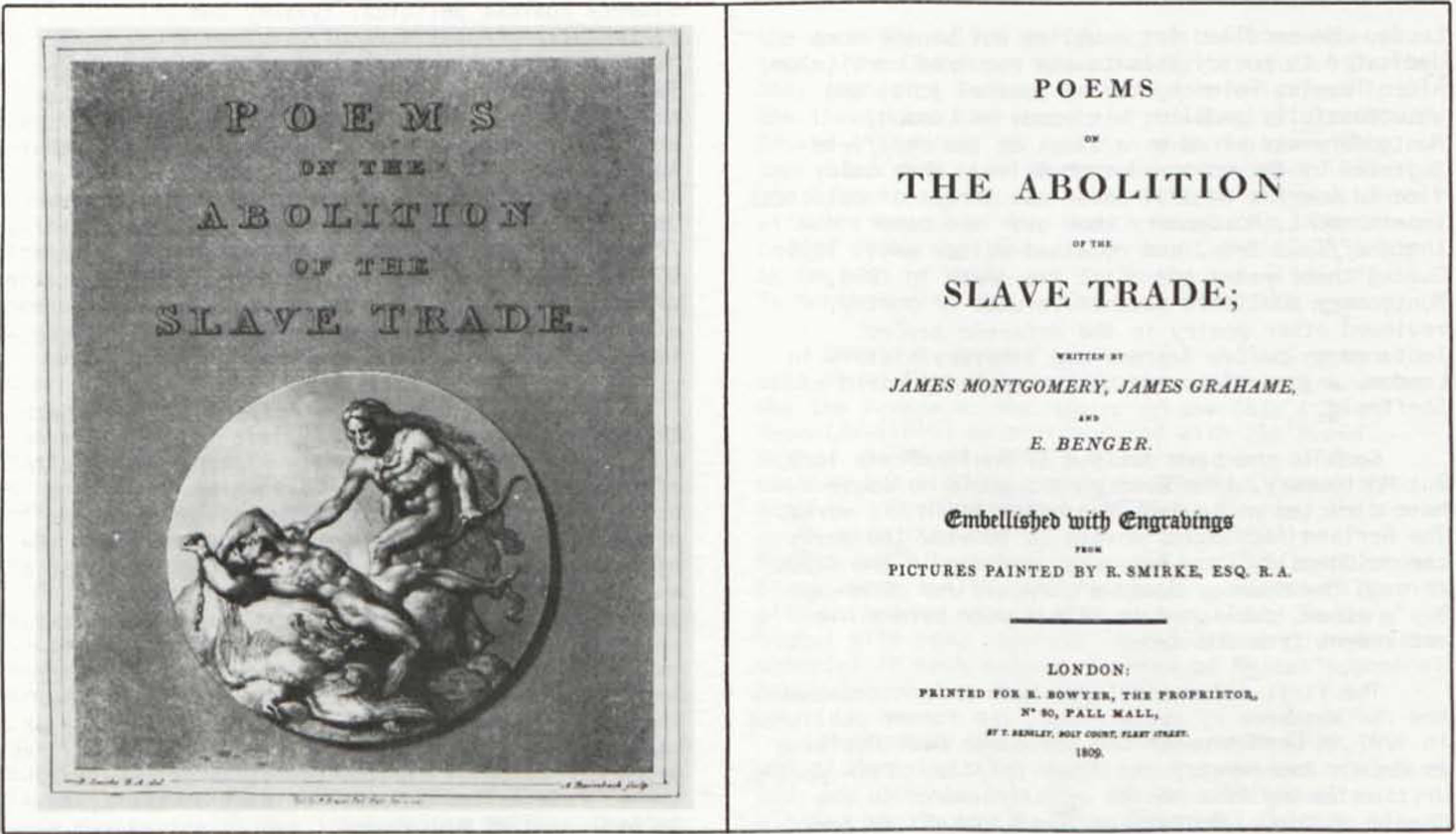

Despite its poetic weaknesses, The Wanderer of Switzerland and other Poems established Montgomery as more than the editor of the Iris. In response to this popularity, Robert Bowyer of Pall Mall asked Montgomery to write a poem celebrating the parliamentary bill outlawing the slave trade in England. Bowyer wanted to publish a volume of several poems accompanied by engravings which would illustrate selected passages. Long devoted to abolition and remembering his parents who died helping slaves in the West Indies, Montgomery wrote The West Indies, a poem which traces the history of the slave trade from the days of Columbus to the present. Besides Montgomery’s poems and engravings by Raimbach, Scriven, and Worthington from illustrations by Smirke, the volume includes shorter poems by James Grahame and Elizabeth Benger, as well as prose sketches of the activities of Granville Sharpe, Thomas Clarkson, and William Wilberforce. Bowyer’s idea was to produce a magnificent volume founded on the principle of making the sister arts “allies” in the cause of freedom. But the distance between

begin page 31 | ↑ back to top conception and execution was great, and the relationship of poetry to illustration has nothing of the imaginative tension of Blake’s illustrated poems. When the book was finally published in 1809 after many printing delays and problems with the engravers, it did not sell quickly, although Montgomery’s later, less expensive edition of The West Indies had a wider circulation.The narrative of The West Indies wanders the globe as Montgomery progresses through the history of the slave trade, showing the degeneration that profiteering in human lives brought on master and slave alike, the one a “tether’d tyrant of one narrow span; The bloated vampire of a living man” (Part III, 11. 235-36) and the other “dead in spirit” and “toil degraded” (Part IV, 1. 59). The poem ends cheerfully with a vision of the entire world renovated from slavery to freedom as a result of British leadership and the establishment of the “church of God” (1. 266) in the wilderness. Choosing to ignore the ambiguities surrounding the slavery debates, Montgomery confidently sees the freedom of all men and women leading to the millenium:

—All hail!—the age of crime and suffering ends;

The reign of righteousness from heaven descends;

Vengeance for ever sheathes the afflicting sword;

Death is destroy’d, and Paradise restor’d;

Man, rising from the ruins of his fall,

Is one with GOD, and GOD is All in All.

(11. 279-84)

Although sincere and passionate, The West Indies often lapses into long sermons on the plight of slaves. Montgomery is too eager for the poem to succeed as social history and rhetoric: he even provides his own footnotes on such works as Clarkson’s History of the Abolition, Captain Stedman’s Narrative of a Five Years’ Expedition (which Blake illustrated), and Mungo Parke’s Travels. Furthermore, the poem suffers from typical formal ailments; Montgomery’s heroic couplets are tiring and his explanations of conventional imagery annoying: “Bondage is winter, darkness, death, despair / Freedom the sun, the sea, the mountains, and the air” (Part I, 155-56).

In The West Indies, which Romantically begins with the origins of history and ends with the “New Creation,” Montgomery planned a poem on a grand scale. Like his greater contemporaries, he also wanted to write an epic poem; he judged his lesser pieces the way Keats more wrongly judged his shorter works: as trifles. Even as a schoolboy Montgomery tried to write epics—one based on Genesis and Milton and the other on the achievements of Alfred the Great. With the example of Milton always before him, Montgomery longed to write of things yet unattempted in prose or rhyme, even though he sensed early in his career that he might never succeed.5↤ 5 During his second imprisonment in York Castle, Montgomery wrote to his friend Joseph Aston of Manchester: “I determined to rival—nay outshine—every bard of ancient or modern times! I have shed many a tear in reading some of the sublimest passages in our own poets, to think that I could not equal them. I planned and began at least a dozen epic poems . . . ” (Memoirs, I, 258-59).

The World Before the Flood, the major poem in the next Garland volume, represents Montgomery’s attempt on a Biblical theme. Inspired by the eleventh book of Paradise Lost, Montgomery set out to write an account of the struggle between the Patriarchs of God and the Giants of the Earth descended from Cain. Montgomery borrows liberally from Paradise Lost, often, it seems, relying on the

begin page 32 | ↑ back to top associations that readers would have with Milton’s imagery and scenes. For instance, when Montgomery wants to underscore the moral and theological confusion of the assembly of Giants, he reminds us of the discord of Pandemonium:A shout of horrible applause, that rentMontgomery wants to give the Giants reality by using the Miltonic context, just as Milton brings the Fallen Angels to life by identifying them with the pagan gods.

The echoing hills and answering firmament,

Burst from the Giants,—where in barbarous state,

Flush’d with new wine, around their king they sate;

A Chieftan each, who, on his brazen car,

Had led a host of meaner men to war.

(Canto 8, p. 146)

In letters written at the time, Montgomery claimed that he was inspired by Milton’s Enoch, one of the Just Men in Paradise Lost, a man like Abdiel and the poet-hero Milton, who resists the temptations of cheap glory. But the focus in The World Before the Flood, as far as there is a center in this loosely-constructed poem, is on Javan, the prodigal poet who returned to the land of the Patriarchs after succumbing to temptations of fame and glory. Montgomery was more attracted to the greater humanity of the flawed poet than to the rock-like Just Man. Like Wordsworth, he was moved by the human misery of the eleventh book, and like Keats, he wanted to see more deeply into the human heart than Milton had.

Montgomery does make the tensions in Javan’s heart seem real, but the character probably interests us more because we view him as a Romantic type, such as Byron’s Cain, than because of the sustained power of Montgomery’s creation. Byron, in fact, may have drawn on Montgomery’s Javan and Zillah for his characters in Cain, although Montgomery creates an orthodox and hopeful fiction. Montgomery’s characters enjoy fellowship because they have first established their faith in a God whom Byron’s Cain sees as an unacceptable tyrant and whom Byron sees as a product of man’s alienation from his own humanity.

The two major interests in The World Before the Flood, the story of Javan’s return and the fate of the Patriarchs who are threatened by the hostile Giants, are not tightly interwoven. Nor is Montgomery’s narrative skillful. The long stories of the history of the race, including the last days of Adam and Eve, do not have dramatic propriety; the storytelling is not structured so that hearing a story changes the way a character looks at the world, as the Bard’s Song inspires Milton in Blake’s Milton or the Wanderer’s tale affects the poet in The Ruined Cottage. Javan has already returned to the flock, at least emotionally, when the poem begins; he doesn’t need to be moved to action by a story. Furthermore, heroic couplets do not give Montgomery enough freedom for the extended periods that add power and variety to long narrative verse.

In the years that he was working on The World Before the Flood, Montgomery considered himself an outcast. After abandoning the Moravian religion of his youth, he lost direct contact with church members, and, while he always considered himself a Christian, he was troubled by restlessness and doubt. At the same time, he yearned for fellowship with other Christians, for the communion and community so central to the Moravian Brethren.6↤ 6 In The Making of the English Working Class (New York: Pantheon Books, 1964), p. 47, E. P. Thompson notes the strong communitarian tradition in the Moravian Brotherhood. Perhaps we can see this yearning in the character of Javan, who gives up what Milton calls “renown on Earth” (PL, XI, 698) and returns to his native land. In any event, in the year following the publication of The World Before the Flood, Montgomery officially returned to the Moravian faith and remained an active member for the rest of his life.

If The World Before the Flood is the story of the prodigal’s return to his faith, Montgomery’s next long poem, Greenland, is a tribute to the faithful, the Moravian missionaries who were risking their lives in an inhospitable land. Greenland—the poem and the country—had been on Montgomery’s mind for years before he finally published the poem as a fragment in 1819. The first three cantos sketch the history of the Moravian church and the first voyage to Greenland in 1733; the fourth and fifth cantos refer to the lost Norwegian colonies of the tenth through fifteenth centuries. The projected cantos were to have dealt with “that moral revolution, which the gospel has wrought among these people, by reclaiming them, almost universally, from idolatry and barbarism” (Montgomery’s Preface, p. vi). Although Montgomery’s reasons for not completing Greenland are unclear, this sketch should indicate the difficulty of using such material with no central plot or character. The most likely assumption is that Montgomery wanted to publish the unfinished poem in order to bolster his campaign in the Iris to save the missions, and simply never returned to it. As if to strengthen the impact of the poem as propaganda, the completed cantos have long, detailed footnotes and appendices on the Moravians, information that the reader of 1819 or today could gather more efficiently from a history text. Such frequent and minute interruptions destroy the rhythmical momentum of long narrative poetry.

Despite these faults, Greenland does contain imaginative descriptive passages:

On rustling pinions, like an unseen bird,What is most striking about Montgomery’s imagery is the apparent influence of Shelley. Throughout Greenland Montgomery describes atmospheres full of energy and movement: rushing meteors, powerful glaciers, expanding vapours, crashing mountain ice, winds yelling like demons. The imagery of Montgomery’s earlier poetry was more static and conventional; but in Greenland his images reflect the harsh and unyielding power of the natural world. Like Shelley in “Mont Blanc” (published in 1817 at begin page 33 | ↑ back to top the end of the History of a Six Weeks’ Tour), Montgomery invokes geological time as well as human history.

Among the yards, a stirring breeze is heard;

The conscious vessel wakes as from a trance,

Her colours float, the filling sails advance;

While from her prow the murmuring surge recedes:

—So the swan, startled from her nest of reeds,

Swells into beauty, and with a curving chest,

Cleaves the blue lake, with motions soft as rest.

(Canto III, pp. 47-48)

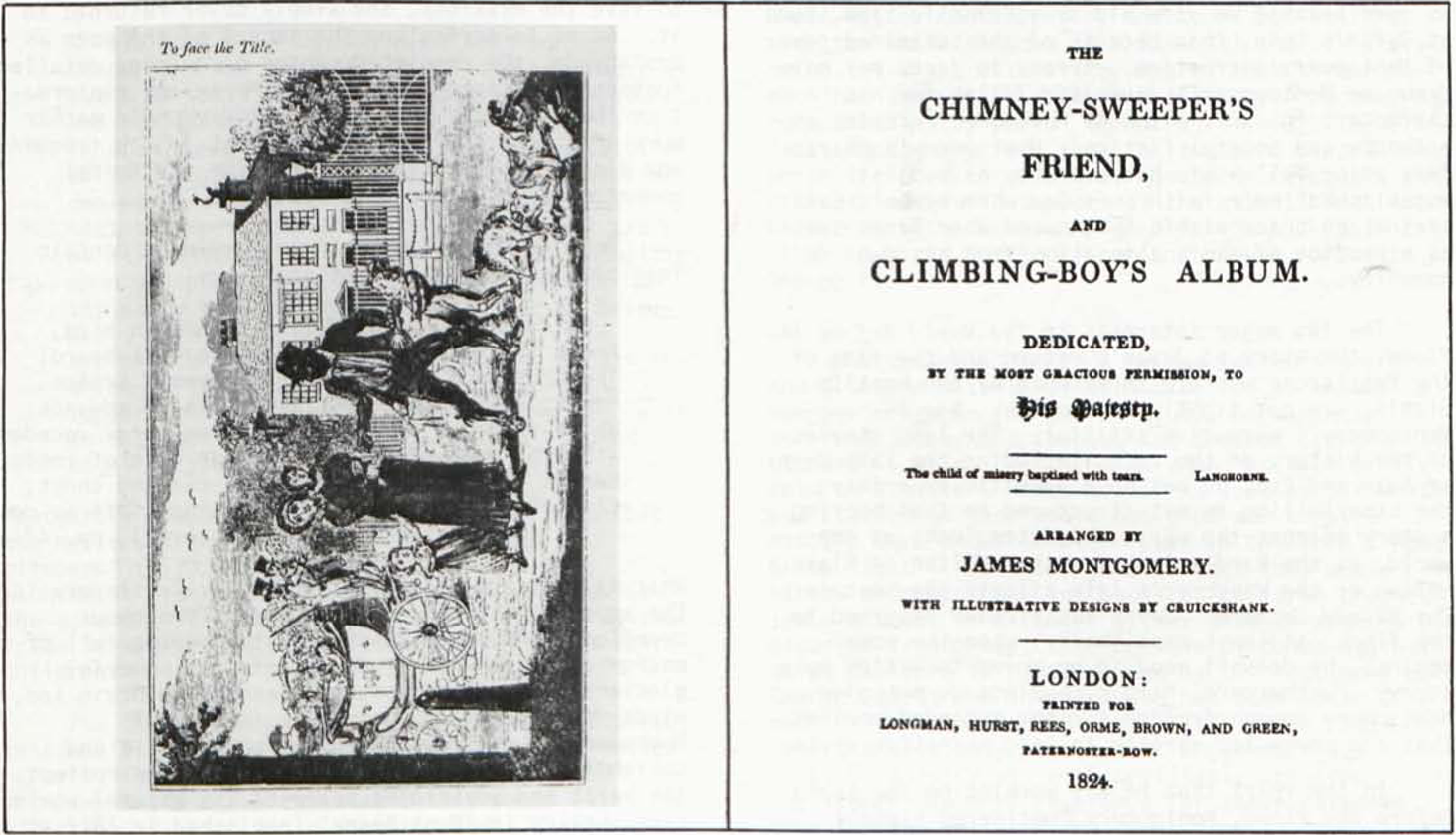

But unlike Shelley, Montgomery did not abhor didactic poetry. He wrote Greenland as veiled propaganda, and even more to the point, he edited The Chimney Sweeper’s Friend and Climbing Boy’s Album for the “direct enforcement of reform.”7↤ 7 I am referring[e] to Shelley’s argument in the Preface to Prometheus Unbound that “nothing can be equally[e] well expressed in prose that is not tedious and supererogatory in verse”[e] (Shelley: Poetical Works,[e] ed. Thomas Hutchinson [London: Oxford Univ. Press, 1968], p. 207). This volume combines actual accounts of abuses with selected poetry, all designed to prove what Montgomery states in the Preface:

This book will exhibit such testimonies concerning the subject, in all its bearings, as ought to satisfy the most supercilious, obdurate, and prejudiced, that such an employment is inhuman, unnecessary, and altogether unjustifiable. The barbarity of the practice cannot be denied:—nor can it be mitigated, for it is next to impossible to teach a child this trade at all, without the infliction of such cruelties upon his person, as would subject a master in any other business to the discipline of Bridewell, were he to exercise the like on his apprentices. Nor can any necessity, except that which is the tyrant’s pleas, be proved in support of it. There are machines in use, with which ninety-nine chimneys out of a hundred might be swept . . . (vi-vii)Montgomery proposes that the legislature “prohibit the masters from taking any more children as climbers” (vii) and replace human beings with machines. His central contrast recurs throughout the volume: Parliament passed a bill outlawing the trade in Negroes but it allows the trade in British children.

The Chimney Sweeper’s Friend consists of pleas, testimonies, case histories, “true” stories, medical reports, legal resolutions, and petitions; the Climbing Boy’s Album contains mostly poems (with the exception of brief prose fictions and a dramatic sketch) illustrating the misery of the “profession.” For the Album Montgomery solicited works from all over the kingdom, getting many responses—mostly from sincere souls rather than literary talents. Some declined to contribute on the grounds that a poem on such a subject would be neither useful nor poetical: Walter Scott responded with instructions (printed in Montgomery’s general preface) for constructing chimney vents so that very little soot accumulates, and what does accumulate can be cleaned with a machine; Joanna Baillie said that such a collection of poems “is just the way to have the whole matter considered by the sober pot-boilers over the whole Kingdom as a fanciful and visionary thing. I wish, with all my heart, that threshing-machines and cotton-mills had first been recommended to monied men by poets” (Memoirs, IV, 61). Nevertheless, Montgomery felt that the two-part miscellany, which included three engravings by Cruickshank, would attract readers in support of the cause. And, hoping to interest the King more deeply in the plight of climbing boys, Montgomery dedicated the volume to George IV.

The Chimney Sweeper’s Friend includes graphic and gruesome details of such miseries as chimney sweeper’s cancer (of the scrotum), permanently deformed limbs, and stunted and crooked growth. The picture is grim: children as young as four or five sold to a master, unwashed for as long as six months, and starved so they would not grow and thrive. Masters were known to stick pins in children’s feet or to light fires under them so that they would climb narrow chimneys; the instances of children dragged senseless out of chimneys either dead or soon to die occurred frequently. The massive evidence against using children is complemented by the testimony of George Smart, who invented and had been using a machine for cleaning chimneys since 1803. But repeated testimony proves that while machines existed, slavery was more profitable and some Englishmen had more reverence for their chimneys than for the children who swept them.

begin page 34 | ↑ back to topBeyond testaments to physical injustices, the selections include subtle personal observation. In an introductory address written by a Mrs. Ann Alexander of York for a pamphlet on the subject, the writer pleads as a mother to mothers:

Could we have endured the idea, that those who had been nursed at our bosoms, with all a mother’s tenderness; those who had repaid the toils of maternal solicitude with the sweet smiles and endearing actions of unconscious innocence; should, at the early age from five to seven years, when probably their natural or acquired dread of darkness was in full operation, be forced into the rough and obscure recesses of a chimney, in the manner described in this pamphlet? (p. 86)Such a detail as the child’s fear of darkness adds poignancy to the evident physical dangers of sweeping. Mrs. Alexander consistently calls attention to the emotional deprivation of the children: “As climbing boys are brought up under those who had their feelings of tenderness early blunted by their disgusting profession, and, who, probably have received little, if any, education themselves; what means of improvement can we therefore suppose such masters will provide for their apprentices?” (p. 88). This kind of life blunts the feelings and affections associated with a child’s development, so that he becomes deformed mentally as well as physically. He is deprived of the natural bonds which connect children to a responsive world.

The theme of mental and emotional deprivation runs through the pieces in the Climbing Boy’s Album. Many of the fictions are based on actual accounts of children either stolen from parents or sold by them to master sweeps. “The Lay of the Last Chimney Sweeper” (pp. 369-77), dated optimistically in the year 1827, tells the story of a child who for a time enjoyed a healthy, free childhood in his native glen; but when his father’s death brought hard times, his mother made her way into the city and was tricked and tempted into bartering her boy.

A sooty man, of mien austere,The lay typically contrasts natural love and country freedom with the corruption of the city. The chimney sweep becomes the outcast from society, marked by soot and deprived of fellowship.

Pursued her steps behind:

Stern were his features and severe,

And yet his words were kind.

Her boy should learn his trade, he said,

Nor would he aught withhold;

He’d lodge him, clothe him, give him bread;—

He show’d the tempting gold.

When too, upon the village green, among the lads I stand,

No friendly voice my presence hails, I press no friendly hand;

I fain would mingle in their sports, but, ah! my brow doth wear

A mark that bids that noisy crew my converse to beware.

(“A Ballad of the House-Tops,” p. 360)

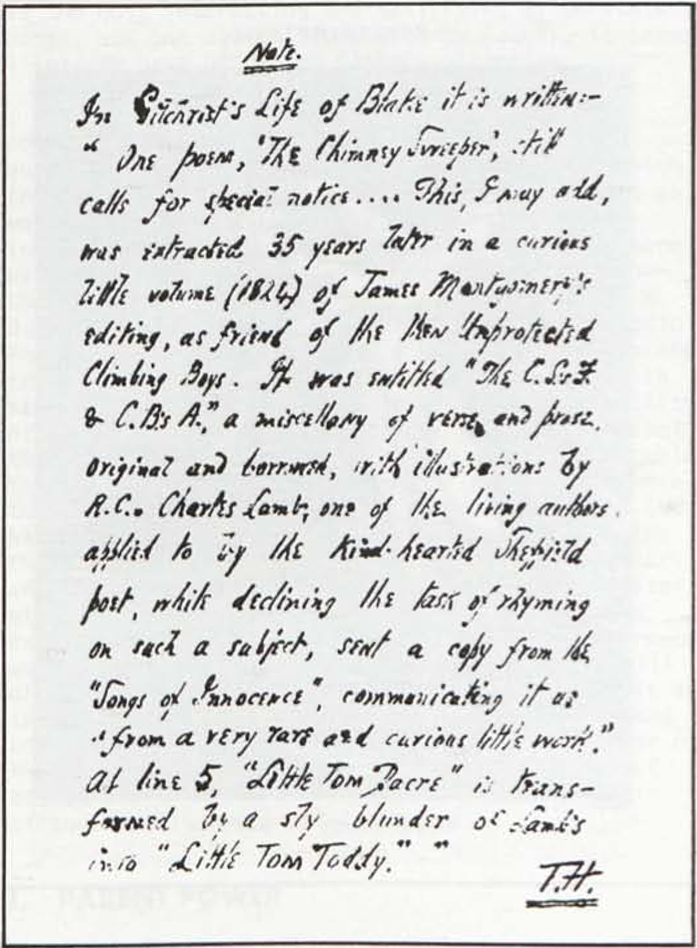

Readers of this journal will be interested to find Blake’s “Chimney Sweeper” from Innocence in the Album, with the explanation that Charles Lamb sent the poem along in lieu of his own contribution. As far as I can tell, Blake and Montgomery had no direct contact, although Montgomery was familiar with some of Blake’s illustrations and owned a copy of the illustrations to Blair’s The Grave.8↤ 8 Holland and Everett say that Montgomery sold his copy because “several of the plates were hardly of such a nature as to render the book proper to lie on a parlour table for general inspection,” and regretted the sale when “the death of the artist soon afterwards rendered the work both scarce and proportionately valuable” (Memoirs, I, 38). It happens, too, that the copy of The Chimney Sweeper’s Friend and Climbing Boy’s Album used by Garland (from Yale’s Beinecke Library) contains on the back leaf a handwritten note that quotes Gilchrist’s comments on a strange alteration that Lamb made in the text:

In Gilchrist’s Life of Blake it is written:—“One poem, ‘The Chimney Sweeper,’ still calls for special notice. . . . This, I may add, was extracted 35 years later in a curious little volume (1824) of James Montgomery’s editing, as a friend of the then unprotected Climbing Boys. It was entitled “The C.S. ’s F. & C. B. ’s A,” a miscellany of verse and prose, original and borrowed, with illustrations by R. C. Charles Lamb, one of the living authors applied to by the kind-hearted Sheffield poet, while declining the task of rhyming on such a subject, sent a copy from the “Songs of Innocence”, communicating it as “from a very rare and curious little work.” At line 5, “Little Tom Dacre” is transformed by a sly blunder of Lamb’s into “Little Tom Toddy.” ”Lamb’s intentions in changing the name (whatever they might have been) are not as significant as his choice of the more ambiguous song from Innocence than the angry one from Experience, in which the sweeper’s parents have gone to Church “to praise God & his Priest & King / Who make up a heaven of our misery.” This choice is more politic in a volume dedicated to the current king and courting his support for the cause. begin page 35 | ↑ back to top

The Chimney Sweeper’s Friend and Climbing Boy’s Album reminds us of Montgomery’s commitment to both journalism and poetry, since some of the selections were first printed in the Iris. This dual commitment set him apart from many of his greater contemporaries. His work as an editor stole time from poetic composition, and even when he finally gave up the editorship of the Iris, he wrote essays, lectured, and participated actively in religious and secular affairs. Blake and Wordsworth, Shelley and Keats, put poetry first, since they considered it the most powerful means of reform: the poet could hammer away tyranny, sharpen the discriminating powers of the mind, legislate quietly over the world. Perhaps Montgomery sensed that his poetry alone could not have exerted a major influence on the spirit of the age.

Montgomery failed because his poetry of sincerity lacks formal discipline and depth of thought. His poems often lapse into a rhetorical and preachy style that cannot rest in imaginative uncertainties; nor does he create his own sustained, coherent poetic system. The faults of much of his poetry resemble those named by Jeffrey in his review of The Excursion (Edinburgh Review [24] Nov. 1814): prolix and long-winded ideas without discipline. Overwhelmed by the sentiments of The Wanderer of Switzerland, Byron claimed in English Bards and Scotch Reviewers that Montgomery’s works “might have bloomed at last” (420) if they had not been “nipped in the bud” by the “Caledonian gales” (422) of the Edinburgh Review. We do not have to agree with Byron to be grateful for the return of Montgomery’s works in the shape of the Garland facsimiles.