article

begin page 132 | ↑ back to topBlake As Conceived: The Endurance of S. Foster Damon

“The study of Blake inevitably leads to controversy; the reader of this dictionary might never guess that there was anything but an agreed orthodoxy.” (anon. rev., “Guides to a New Language,” 3 Oct. 1968)*↤ Reprinted with minor alterations from S. Foster Damon’s A Blake Dictionary, by permission of the University Press of New England, ©1988. A paperback edition of the second printing of Damon’s Dictionary, with a new preface, an annotated bibliography, and index by Morris Eaves, will be issued in April 1988 by the University Press of New England.

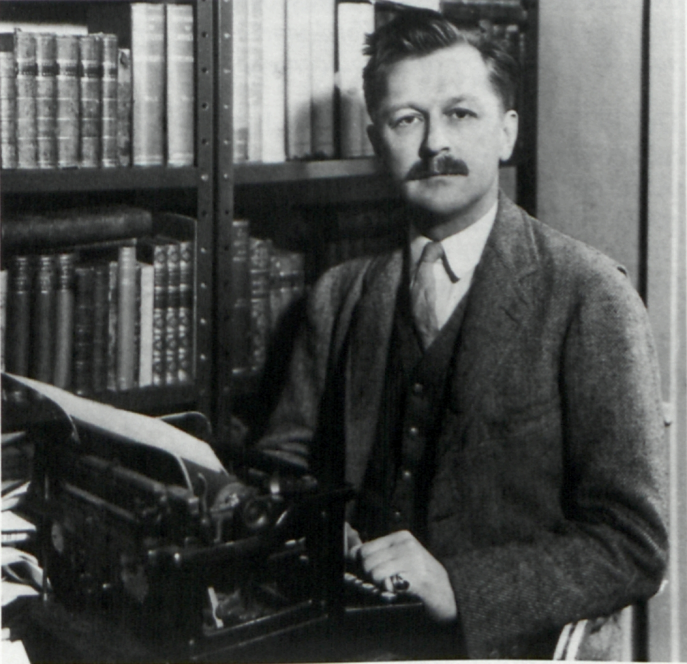

S. Foster Damon was the young Turk of Blake studies when William Blake: His Philosophy and Symbols was published in 1924. He was “the patriarch of Blake studies” (Bloom rev., 24) when A Blake Dictionary: The Ideas and Symbols of William Blake was published in 1965. As I write this preface, Philosophy and Symbols is more than 63 years old, A Blake Dictionary more than 22, and Damon has been dead since 1971. It’s fair to ask what A Blake Dictionary is good for at this late hour. Though Damon loved to pore over patriarchal tomes himself, he would have understood that people entering strange territory want up-to-date guidebooks. When I started getting serious about Blake, my guides were Northrop Frye’s Fearful Symmetry (1947), David Erdman’s Blake: Prophet against Empire (1954), and Damon’s Dictionary. That was 1968, after all, and the Dictionary was nearly new. But today I’d still endorse my own experience: if Blake is where you’re going, Frye, Erdman, and Damon should be your guides. As an introductory offer they remain unbeatable.

To understand the power of the Dictionary in this durable trio, we start with the recognition that Damon’s lifetime coincided with the institutionalization of Blake. The process began well before Damon arrived on the scene and may continue indefinitely, but the crucial decades were those bracketed by Damon’s Blake books. From the 1920s through the 1960s, various factors co-operated to assign to the name “William Blake” a set of attributes and a location in history. The rough consensus

achieved during Damon’s lifetime is by and large the one we are still operating with today—the one that leads us to expect to find William Blake at home in one of the six slots allotted to the so-called major English romantic poets in standard textbooks devoted to the standard subject of English romantic poetry.To the extent that the Blake of Damon’s Philosophy and Symbols is the same as the Blake of the Dictionary in most essentials, the Dictionary is an annotated index to its own predecessor. The sustained equilibrium in the meaning of “Blake” that made it possible for a book published in 1965 to re-present a book published in 1924 has less to do with the consistency of the author than with the consistency of the scholarly institutions begin page 133 | ↑ back to top within which he operated. Not that he or they never changed or learned anything new during all those years. But the fact that the Blake Damon calls to memory for his Dictionary is very largely the Blake first assembled for his Philosophy and Symbols four decades earlier confirms not just Damon’s stubborn faith in his own critical powers but also the capacity of institutions to remember what they need to remember and to build on that memory while staunchly forgetting what they need to forget.

“Damon’s . . . Philosophy and Symbols (1924) has been the foundation stone on which all modern interpretations of Blake have built” (Bateson rev., 25). Having laid the foundation in the 1920s, it was only proper for the poineer to return to it in the 1960s with a late scholarly tribute to his own work. By then a flourishing public building was standing on the site, occupied by a mostly academic staff that some observers (not I) have identified as the middle management of a veritable Blake industry. As a scholarly resource, Damon’s Dictionary has stood up as well as it has for as long as it has because it belongs to that collective effort. Some reviewers pointed out what they saw as a discrepancy between the impersonality of a proper dictionary and the “eccentric and occasionally oracular” (Erdman rev., 607) personality of this one. Damon himself played up the independence that made his compilation A, not The, Blake Dictionary: “It is not the intention of this book to compile digests of the works of other scholars or to confute their theories. I have felt it better to make a new start and to attempt to present fresh evaluations of Blake’s symbols” (Dictionary, xii). To the contrary: at the nucleus the Dictionary is precisely a digest of Damon’s ideas that had become common property—refined, expanded, and occasionally changed under the influence of other scholars’s ideas that he had found congenial. Consequently, even as he insisted on his independence, he regularly acknowledged his institutional position, as with his gestures toward scholarly posterity: “When a final answer has not been possible, I have tried to assemble the material for others to work on” (Dictionary, xii; also xi). Many of the parts of other scholars’s works that Damon refused to digest were, after all, the peripheral parts for which no consensus yet existed. And his own attempts at “new” starts and “fresh evaluations” are, for the most part, simply the parts of the Dictionary one must learn to ignore. Fortunately those are few, and they usually advertise their own peculiarity.

The best reason for studying Damon is neither to acquire a real English Blake from the bowels of history nor a curiosity Blake from the fascinating mind of an eccentric scholar but to acquire the Blake that unglamorously satisfies the rules and requirements of our institutions of artistic memory, in which Damon lived and thrived. He later said it himself, with irony and unmistakable pride: “At last, Blake was academically respectable” (“How I Discovered Blake,” 3)—made respectable by an academic whose work of Blake scholarship had been rejected by Harvard as too inconsequential to merit a Ph.D. Thus what we have before us in the Dictionary is undeniably a sturdy Blake, well crafted for the very purpose of being remembered, read, taught, and written about within our institutions of reading, teaching, and writing. Of course, despite its endurance, we would never want to mistake this brilliantly conceived Blake for the only conceivable Blake. Nor, however, can we pretend that we presently know how to conceive any other Blake of comparable usefulness. In short, the essence of the Blake who materializes in the pages of Damon’s Dictionary is nothing less than the presently indispensable Blake. And only that indispensability makes it matter in the least that the Dictionary is “a rich treasury embodying the results of a lifetime of masterly and devoted research into every aspect of Blake’s work and thought” (Pinto rev., 153). Yes, the treasury is rich. Equally important, it is the coin of the realm.

Needless to say, Damon’s academically respectable Blake did not come from nowhere. Even by 1924 the way had been well prepared. The single most important event in the history of Blake’s reputation had already occurred. It was, essentially, a solution to the problem of Blake’s double mastery of words and pictures, which made it very difficult to achieve a good fit between Blake’s works and the structures that commit poets and painters to different kinds of institutional memory. Today’s academic division between departments of art and departments of English reflects and extends a separation with an extensive history both inside and outside institutions of higher education. Though it has become routine in the later twentieth century to celebrate Blake’s magnificent twofold achievement in art and literature, that boast could only begin to register effectively at a certain ripe and recent historical moment. Until then, for all practical purposes Blake’s doubleness was a kind of duplicity, an indigestible alliance, like a dessert combined with an entrée.

Blake died, after all, in 1827 as an engraver and painter in a circle that included mainly engravers, painters, and buyers of art. He was barely known to the writers such as Wordsworth and Coleridge with whom he is now yoked in anthologies of English romantic poetry. As that pair of statements indicates, the fundamental change in Blake’s reputation occurred when history found a way to conclude that he is essentially a poem-maker rather than a picture-maker. The change began to come on strongly in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, with the efforts of Algernon Charles Swinburne, William Michael Rossetti, and others to produce editions of Blake’s poems. Since many of those “poems” were originally crafted as “illuminated books” in “illuminated printing”—usually relief-etched and watercolored combinations begin page 134 | ↑ back to top of text and design—they were doomed to run afoul of the institutional standards for poetic legibility. The first duty of an editor is to present poems. We all know what poems look like: in such an edition pictures may be present as ornaments and illustrations but not as integral poetic ingredients.

Blake the printmaker and painter was not forgotten; in some narrow circles his art was even revered. But on the larger cultural stage the emphasis was steadily shifting from the visual element in his work to the verbal, and the memories of his literary and artistic work were being stored ever more systematically in separate cultural compartments. The institutions of literacy edited the illuminated books into poems, lowering the visual component to the status of the ornamental and the dispensable. Meanwhile, the institutions of imagery operated by art historians, collectors, and curators looked past the illuminated books—the mainstay, curiously, of Blake’s literary reputation—toward the categories of Blake’s oeuvre where pictures rather than words are primary, because there he most clearly conforms to the conventional definition of a visual artist.

These moves to separate words from images were portentous. On the side of the literary institutions, where most of the action was, the decision to regard the component of visual design in Blake’s product as a separate rather than integral part of his work had the curious effect of transforming the design component from a disadvantage (how does one reproduce these illuminated plates for consumption; having reproduced them, how does one read them?) to a minor advantage. As long as Blake’s visual art did not have to be coordinated systematically with the verbal in the process of interpreting, the visual art could signal his surplus creativity—his difference from the norm and even from the five romantic poets to whom his future was beginning to be tied. Thus, as long as the illuminated books did not have to be reproduced as illuminated books, as long as they could be edited, printed, interpreted, and taught as poems, the visual element of the work could serve handily as a kind of place-holder in accounts of Blake, marking his difference from the rest of his poetic family. Meanwhile, in the practice of literary criticism the visual element could have the (diminished) role of an optional rhetorical opportunity rather than a haunting, forbidding obligation that no practicing critic would know how to live up to. Moreover, as the burden of responsibility for Blake’s reputation shifted from the institutions of art history and art collecting to the institutions of literary history and criticism, some major impediments to a favorable appraisal of Blake—such as the entrenched orthodox standards of drawing—became much more manageable. After all, the literary types in whose hands Blake’s fortunes lay cared little and knew less about such orthodoxies.

It was not for nothing, then, that Foster Damon traced the beginning of his serious study of Blake to a literary edition: “The present study of the philosophy and symbols of William Blake was begun ten years ago, when Dr. Sampson’s edition of Blake’s Poetical Works made most of the texts accessible in their correct form” (Philosophy and Symbols, vii). Sampson’s edition had in fact first been published in 1905 but Damon used the “Oxford Edition” of 1913, 1914, and later printings. In any event, we can see from his comment how Sampson’s meticulous edition had helped codify a conception of Blake the poet. Now the question would be, what kind of poet?—ans. a sort of modernist. Damon’s “ten years ago” had been around 1914, one of the three years when the older William Butler Yeats and the younger Ezra Pound spent the winter at Stone Cottage in Sussex together, plotting the next stage in the history of modern poetry. “Philosophy and symbols” had already become part of that history and were destined to become much more important parts with Yeats’s increasing devotion to the kind of philosophical symbolism that culminated in A Vision (1925). Blake had already influenced the development of Yeats’s symbolism, and Yeats with his collaborator Edwin J. Ellis had edited Blake’s complete works with two volumes of commentary in 1893. Damon once called the first volume “unreadable” (“How I Discovered Blake,” 2)—and indeed it took a Foster Damon to write a readable replacement for Yeats and Ellis—but that should not be taken to suggest that we can understand Damon’s Blake without understanding the decisive alliance between Blake’s literary fortunes and the fortunes of modernism.

Blake’s system-making, his blend of psychology with religion, his exalted claims for the powers of art, the difficulty of his work, and his failure to win an audience in his lifetime are only a few of the several factors that cooperated to make him a potential artist-hero and guardian angel of a significant filament of modern poetry—not necessarily the strand that was spare and taut in its verbal standards, but the mythopoeic strand that wanted to make poetry the cult-object for an elite society of initiates who would deal only in the deepest, most significant kinds of knowledge of which the world at large was unworthy. This helps to explain why Damon’s Blake is “definitely a mystic,” as Damon says he discovered by reading William James’s Varieties of Religious Experience (“How I Discovered Blake,” 2). We would hardly be the first to notice that Damon’s Blake is a mystic of a particularly artistic persuasion, for whom the traditional goal of seeing the face of God becomes a vision of imagination—a magico-aesthetic mysticism closer to the Order of the Golden Dawn, the late nineteenth-century occultists, and poets like Yeats than to the author of The Cloud of Unknowing.

begin page 135 | ↑ back to topWe haven’t space here to trace the affiliations with modernism that helped shape an academically respectable Blake: a mystic but also, as Damon’s title advertises, a philosopher and symbolist. In the game of institutionalization finding powerful metaphors is an important maneuver, and Damon’s three favorites had all the right connections at the time. But in the long run Blake-mystic and, to a large extent, Blake-symbolist, at least, fell away as inadequate anachronisms. Their historical connections with the period of Blake’s discovery, the roughly fifty years from 1875 to 1925, became more apparent than their connections with Blake’s texts. But a variety of other, analogous terms have had to be brought in as substitutes, simply because some mode of identification is required.

The metaphors continue to shift, but so far the general need that they try to satisfy has changed much less. R. P. Blackmur once expressed that need well in his essay on “A Critic’s Job of Work,” which uses Damon’s own Philosophy and Symbols as an example of that job properly done: “. . . Mr. Damon made Blake exactly what he seemed least to be, perhaps the most intellectually consistent of the greater poets in English” (qtd. Morton D. Paley in Damon, “How I Discovered Blake,” 3n). Blackmur registers precisely the combination of surprise and relief that has become characteristic of Blake’s reputation—or, we might say, characteristic of the narrative that is told repeatedly to justify his inclusion among the “greater poets.” At least in the twentieth century, the surprise of discovering a poet who is consistent has been a reliable part of the stories that readers tell about their relationships with Blake, and those four terms have been basic indices of his place in our literary institutions.

In discussing the literary elements in the growth of Blake’s reputation, I would not want to give the impression that Damon’s Philosophy and Symbols eliminated Blake’s art from consideration. To some extent, especially by comparison with the literary scholars who would come later, he did the opposite. The last section of Philosophy and Symbols commented, however briefly, on each plate of the illuminated books, while other books on Blake often left the designs unmentioned. But Damon segregated the designs into little clusters under the heading “decorations,” interpreted them as extensions of meanings gleaned first from the poetry, and relegated them to the back of his book where they can easily be forgotten. The best evidence of their forgettability comes with the Dictionary, where Damon eliminates the design component of illuminated printing as a subject of systematic discussion. The justification for doing so—in a presumably unabridged Blake dictionary that one literary-minded reviewer called “extraordinarily comprehensive” (Bateson rev., 25)—is left implicit. It is again, of course, the metaphor that made most twentieth-century advances in the study of Blake possible: Blake is a poet. And he is that kind of poet who uses words as “tools . . . to rouse with thought” (Philosophy and Symbols, xi), a philosopher. As Damon said emphatically, “Jerusalem, as pure poetry, is obviously inferior to the Songs of Innocence. . . . Blake was not trying to make literature. Truth, not pleasure, is the object of all his writings” (his emphasis; Philosophy and Symbols, 63).

As Damon indicated, to find Blake the thinker one travels well beyond Songs of Innocence (“The lyrics are in every anthology; yet professors of literature wonder if the epics are worth reading!” Philosophy and Symbols, ix) into the territory of the “epics” (as Jerusalem can be termed only if considered a literary work), where thought takes precedence over pleasure—as it must, if Blake is to be taken seriously enough to deserve his place beside Wordsworth and Coleridge. Damon passed this version of Blake the philosopher into literary history, where it was eventually taken up by Northrop Frye, who depended fundamentally upon the model of Blake designed by Damon. The Blake of Fearful Symmetry (1947) is even more exclusively a writer than Damon’s, an even more profound thinker, and an even more consistent one. Frye’s Blake is no longer a mystic—the appeal of that metaphor had dissolved in the mists of modernism—but he is very much a philosopher. When Damon combined philosophy and symbolism he got mysticism; when Frye combined them he got myth. Myth, for Frye, is not unlike mysticism for Damon: both are terms for thinking at a particularly profound level that in previous centuries would have been identified with religion. Damon would not refuse to allow that Blake was a Christian, but he knew he had to be an especially appealing kind of Christian, a “Gnostic” Christian, said Damon (Philosophy and Symbols, xi), or a mystic. Frye went a step further by relentlessly exploiting the implications of a new metaphor: religion, deeply considered and thawed out, is poetry. Both draw on the same myths. Blake’s revelations as a thinker, then, are myths that reveal the fundamental nature of poetry itself.

David Erdman, the third member of our trio of resources, came in to do a job that desperately needed doing by the mid-1950s. He relied heavily on the Blake of Damon and Frye, the philosophically consistent thinker more poet than painter and more interested in truth than pleasure, as the basis for Blake: Prophet against Empire (1954). Erdman’s great revision in the licensed image of Blake involved little change at the base. Damon and Frye’s Blake was a man of universal ideas; we learn to read him by reading through a confusing welter of particulars into general patterns of thought. Erdman’s Blake we read in reverse, back from those general patterns of thought into particulars, and then we use the begin page 136 | ↑ back to top particulars to align the patterns with everyday events in London. Erdman’s work augmented the impression already established of a profound Blake, whose concern, though with everyday events, was with the most elevated aspect of those events: liberty, justice, fraternity, equality. In bringing him down to earth, Erdman paradoxically managed to create an even more formidable Blake, a both-and rather than an either-or thinker whose poems could deliver simultaneously profound truths about poetry and equally profound reactions to local events. And, like Damon and Frye, Erdman reinforced the element of surprise in discovering again a consistent thinker, this time a consistent social and political thinker, where before we saw none. When Damon returned with his Dictionary two decades after Frye’s book and a decade after Erdman’s, he had no trouble recognizing the Blake he found. This augmented, fortified, and considerably refined Blake, though now a celebrity much in demand to ornament the books of scientists, literary theorists, theologians, and philosophers, was still recognizably the Blake whom Damon had introduced to the academy in the 1920s, now ready to be represented by a scholarly instrument as impartial and consensual as a dictionary.

From our vantage point more than than two decades later, we can now see that Damon’s Dictionary arrived just in time to signal the end of an era of definition and the beginning of an era of rapid consolidation and codification—with, certainly, some evolution. As many significant additions to our knowledge of Blake as there have been over the years since the Dictionary, most have been additions to the base. One important alternative image has been a changing, as opposed to a consistent, Blake. We might speculate about what motivated the creators of a monolithically stable Blake: the need to hold a difficult subject still long enough to get a focused likeness, perhaps, and, more important, the need to deny the possibility that Blake might be intellectually erratic—even insane. If so, then a consistent Blake was the required precursor of any (memorable) Blake less consistent. The way for a Blake who changes his ideas significantly over the course of his life was already prepared for to some extent by Erdman, whose focus on political ideology almost necessarily brought change into the picture, though it must be said that Erdman’s Blake is notable for his stubborn refusal to change with the tides of English opinion on the French Revolution—and in that way belongs in the family with Damon’s and Frye’s.

The more important product of our new knowledge is a Blake more in line with the historically situated engraver and painter. Although the advances in understanding Blake as an artist have been major, nonetheless they have chiefly proceeded from the prior understanding of Blake as a writer and remain subsidiary. The main categories of analysis have been preserved. In fact, with a very few notable exceptions, most of the scholarship on

Blake’s visual art has been done by English professors working out of their areas of specialization. Understandably, they have eased the difficulties of their transition by importing their literary understanding of Blake. In their terms, Blake the artist works by analogy alongside Blake the writer. Meanwhile, the position of Blake among the art historians has not altered profoundly in recent years. He has greater name recognition among them and perhaps somewhat greater respectability, and, at last, a relatively complete kit of scholarly tools for art historians. Even after these modifications to the scholarly base, however, so far no rumblings in recent art history suggest an imminent change comparable to Blake’s twentieth-century ascendancy among the romantic poets.The nineteenth century made it impossible for readers of the twentieth to “discover” Wordsworth or Keats. The same fate may befall Blake in the twenty-first century. W. J. T. Mitchell’s often cited article on “Dangerous Blake” recognized the sobersidedness and the unmitigated sublimity characteristic of the established Blake. Mitchell’s prophecy that “we are about to rediscover the dangerous Blake, the angry, flawed, Blake, the crank . . . the ingrate, the sexist, the madman, the religious fanatic, the tyrannical husband, the second-rate draughtsman” (410-11) seemed a symptom of the need to reinstitute surprise in the Blake canon—and of a fear that a Blake who can’t surprise his readers may not be able to hold his place. In the half-decade since Mitchell’s article, though progress has continued, no new era has begun. Meanwhile, however, the consolidated Blake holds his own, along with Frye’s Fearful Symmetry, Erdman’s begin page 137 | ↑ back to top Blake: Prophet against Empire, and Damon’s Blake Dictionary, to make them the oldest surviving threesome in literary studies of comparable influence, and, to my knowledge, the best. Not that there is any reason to suppose that we have seen our last Blake. Like all such “figures,” as we call them, in the history of the arts, Blake is one name that can cover many mutable and even incompatible things. Literary and art history have called many Blakes to our attention and will call many more. Many are called, but few are chosen.

Works Cited

Bateson, F. W. “Blake and the Scholars: II.” Rev. of A Blake Dictionary. New York Review of Books 28 Oct. 1965: 24-25.

Blackmur, R. P. “A Critic’s Job of Work.” The Double Agent: Essays in Craft and Elucidation. New York: Arrow, 1935.

Bloom, Harold. “Foster Damon and William Blake.” Rev. of A Blake Dictionary. New Republic 5 June 1965: 24-25.

Damon, S. Foster. A Blake Dictionary: The Ideas and Symbols of William Blake. Providence, R.I.: Brown UP, 1965.

- - -. “How I Discovered Blake.” Blake Newsletter 1 (winter 1967-68): 2-3.

- - -. William Blake: His Philosophy and Symbols. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1924.

Ellis, Edwin J., and William Butler Yeats, eds. The Works of William Blake, Poetic, Symbolic, and Critical. 3 vols. London, 1893.

Erdman, David V. William Blake: Prophet against Empire. 3rd ed. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1977 [1st ed. 1954].

Erdman, David V. Rev. of A Blake Dictionary. JEGP 65 (1966): 606-12.

Frye, Northrop. Fearful Symmetry: A Study of William Blake. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1947.

“Guides to a New Language.” Rev. of A Blake Dictionary. Times Literary Supplement 3 Oct. 1968: 1098.

Mitchell, W. J. T. “Dangerous Blake.” Studies in Romanticism 21 (1982): 410-16.

Pinto, Vivian de Sola. Rev. of A Blake Dictionary. Modern Language Review 65 (1970): 153-55.

Sampson, John, ed. The Poetical Works of William Blake. London: Oxford UP, 1913 (and later printings).