ARTICLES

Young William Blake and the Moravian Tradition of Visionary Art

↤ *All citations from Blake are from The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake, ed. David V. Erdman, newly rev. ed. (New York: Anchor-Doubleday, 1988), abbreviated “E”.The Scripture says that our entire work of the Gospel is to portray Jesus, to paint Him before the eyes, to take the spirit’s stylus and etch—yes, engrave—the image of Jesus in the fleshly tablets of the heart....

Zinzendorf, Nine Lectures 81

I would choose Fancy rather than Philosophy. Feeling is ascertained by Experience; Reasoning is hurtful, or makes us lose ourselves.

Zinzendorf in Rimius, Candid Narrative 48

Thank God I never was sent to school

To be Flogd into following the Style of a Fool

Blake (E 510)*

In the months following the publication of Davies and Schuchard, “Recovering the Lost Moravian History of William Blake’s Family,” more material on Blake’s mother and first husband was discovered in the Moravian Church Library, Muswell Hill, London. We learn that Catherine and Thomas Armitage had a child, Thomas, who died in March 1751; thus, William Blake is actually her fourth, not third, child.1↤ 1. Moravian Archive, Moravian Church House, London: C/36/7/5, p. 10 (1 March 1751). I am grateful to Lorraine Parsons, archivist, for assisting me with research and for sharing the new findings with me. We also learn that the Armitages were intimately and practically involved in Moravian affairs and that Peter Boehler, the charismatic leader of the Congregation of the Lamb, made a special effort to help Catherine after her husband died on 19 November 1751.2↤ 2. Moravian Archive: C/36/14/2 (13 August 1750); C/36/11/6 (12 September, 20 November, 4, 11, and 19 December 1751). An intriguing note on 20 March 1753 urges Brother West, an Armitage-Blake family friend, to speak to “Sr. Arm.” (Sister Armitage?) about some financial matter, thus suggesting that she continued her contacts with the Moravians even after she married James Blake in October 1752.3↤ 3. Moravian Archive: C/36/11/6 (20 March 1753). Perhaps she withdrew only from the highly selective, time-consuming congregation and not from a less formal association with the Brothers and Sisters. If the John Blake who appealed to Boehler for membership in the congregation was indeed the brother of James Blake, Catherine’s new husband, then William Muir’s claim (made to Thomas Wright) that William Blake’s “parents attended the Moravian Chapel in Fetter Lane” gains new plausibility, for they could have attended the services which were open to the public (Wright 1: 2, Lowery 14-15, 210n57).4↤ 4. Keri Davies is currently investigating the many references to Blakes in the archives, which suggest—but do not yet prove—that some of James Blake’s relatives were Moravians. Wright’s further assertion that “Blake’s father had adopted the doctrines of Swedenborg, whose followers, however, did not separate from other religious bodies till later” gains a new historical context, for the Armitages and Blakes could have known or heard about Swedenborg, who also attended services at Fetter Lane in the 1740s and, even after breaking with the Brethren, continued to have Moravian friends and to utilize Moravian publishers.5↤ 5. For Swedenborg’s Moravian experiences in London in 1744-45, see Swedenborg, Dream Diary 12-17, 30-38, 54-58. He wrote more about the London Moravians in his Spiritual Diary (1746-65). Swedenborg used the Moravian publisher John Lewis and, after Lewis’s death in 1758, his Moravian widow Mary Lewis continued to sell Swedenborg’s works. Many of his readers (in England and Sweden) had Moravian parents (such as C. B. Wadström and the Nordenskjöld brothers), while Dr. Husband Messiter, Jacob Duché, and Richard Cosway were interested in Zinzendorf’s teachings. While the Moravian-Swedenborgian milieu raises many questions and provokes many speculations concerning William Blake’s spiritual and intellectual development, I will here focus on the possible Moravian influence—especially through his mother—on his early artistic development.6↤ 6. For background on the Moravian-Swedenborgian milieu, see Schuchard, “Why Mrs. Blake Cried,” written before my discovery of the Armitage-Blake documents at Muswell Hill, and Why Mrs. Blake Cried passim.

In 1828 John Thomas Smith recalled that Blake as a child showed “an early stretch of mind, and a strong talent for drawing,” while also demonstrating the ability to compose and perform “singularly beautiful” songs, despite being “entirely unacquainted with the science of music” (Bentley, BR[2] 605-06). Two years later, Allan Cunningham wrote that “the love of art came early upon the boy,” who “it seems, was privately encouraged by his mother.” It was “his chief delight to retire to the solitude of his room, and there make drawings, and illustrate these with verses, to be hung up together in his mother’s chamber” (Bentley, BR[2] 628, 631-32). From his earliest years, he also revealed his visionary tendency, reporting at age four that he saw God put his forehead to the window and, when he played outdoors, he saw a tree filled with angels and the prophet Ezekiel under a tree. Despite his mother’s worry at such excited claims, she usually protected him from a “thrashing from his honest father” (Gilchrist, quoted in Bentley, Stranger 19-20). Unfortunately, nothing more emerged about this important maternal influence, leading Alexander Gilchrist to lament in 1863 that after the death of Blake’s mother at age seventy in 1792, “She is a shade to us, begin page 85 | ↑ back to top alas! In all senses: for of her character, or even her person, no tidings survive” (Gilchrist 1: 95).

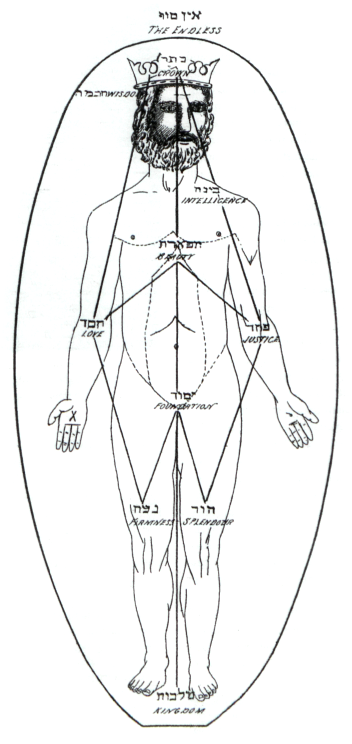

Fortunately, the new Moravian documents allow us to put some flesh on the shade of Catherine Armitage Blake and to recover the religious milieu that rendered her so sympathetic to her son’s development as a visionary artist. In order to bring to the surface this submerged history, it will be necessary to discuss briefly the career of Count Nikolaus Ludwig von Zinzendorf, leader of the renewed Unitas Fratrum, and the spiritual-artistic ethos of the “Sifting Time” (c. 1743-53), a turbulent and creative period of spiritual, sexual, and artistic experimentation.7↤ 7. Moravian historians differ on the length of the Sifting Time, but I date it generally from 1743, when Zinzendorf returned from Pennsylvania, to 1753, when a publishing campaign against him began in England. Though some Moravian officials attempted to suppress the radically eroticized spirituality from 1749 on, the themes continued to attract many members in London and elsewhere but were handled with much greater secrecy. That Catherine and Thomas Armitage, John Blake, and possibly James Blake were attracted to the Moravian Chapel during the most intense years of the Sifting Time would become relevant to William Blake’s later radical and antinomian beliefs about eroticized spirituality. Through this association, they enjoyed unusual—even unique—access to an international network of ecumenical missionaries, an esoteric tradition of Christian Kabbalism, Hermetic alchemy, and Oriental theosophy, along with a European “high culture” of religious art, music, and poetry.

The beliefs and activities of Count Zinzendorf (1700-60) continue to provoke controversy among historians, with most praising him as an innovative theologian and pioneer of religious and racial toleration and some condemning him as a Gnostic heretic and sexual pervert.8↤ 8. For an introductory biography, see Arthur Freeman. For the most accurate histories of the Sifting Time, see Podmore; Peucker, “Blut”; Atwood, Community. Born in Dresden, Saxony, to an aristocratic Lutheran family, he rejected his Pietist mentors’ emphasis on ascetic self-denial and morbid spiritual struggle. In 1722 he welcomed to his estate a band of Moravian refugees, heirs to the Protestant reform movements stimulated by Jan Hus in the fifteenth century and Jan Amos Comenius in the seventeenth. Known as the Unitas Fratrum, the persecuted Moravians preserved “the Hidden Seed” of their irenic spiritual traditions, while they assimilated concepts and symbols developed by Boehmenist and Pietist writers. Under Zinzendorf’s leadership at Herrnhut and other communities, the Moravians developed a passionate Herzensreligion (religion of the heart), which affirmed that Jesus’s Menschwerdung (“humanation”) made him experience the full range of human pain and pleasure and that his self-sacrifice and intense suffering on the cross were sufficient to fully redeem fallen human beings. Thus, pious and self-righteous standards of behavior, which led to hypocrisy and joylessness, were not the proper expressions of Christian worship, for one should utilize one’s Herz (heart) to sensate Jesus’s love and to identify

Drawing on his Hebrew studies and discussions with mystical Jews, Zinzendorf identified the German Herz with the Hebrew Lev, the location of emotion and intellect: “In the Old Testament, heart [Lev] is the point of contact with God. ‘Heart’ is more visceral and affective than the Greek word for the personality [Psyche]” (Atwood, Community 32-33). Moreover,

Zinzendorf defined “Heart” as the inner person which had five senses as did the outer person. The “Heart,” especially when it has been brought to life by the Holy Spirit, can perceive the Savior objectively and directly. In modern terms we might speak of this as “intuition” or “extrasensory perception.” Zinzendorf’s approach is very similar to Teresa of Avila’s “intellectual vision.” (Arthur Freeman 7)In a typically irenic assimilation, Zinzendorf affirmed that the sensually perceptive Lev could be stimulated to “intellectual vision” by meditating upon great religious art, especially the Catholic art produced by Renaissance and Baroque painters. Thus, he argued against the Old Testament prohibition of “graven images,” which influenced the intense iconoclasm of begin page 86 | ↑ back to top most British Dissenters, and praised the Lutheran rejection of that commandment:

In the New Testament this commandment is at an end: we have seen. Therefore the Lutherans are right in leaving this commandment out of the catechism, for it no longer has any relation on earth to us. This makes the particular distinction between us and the Reformed, for they combine the ninth and tenth commandments to make room for the commandment forbidding images, which we Lutherans . . . leave out of the Decalogue. We do not hold that a person should make himself no picture or image in the New Testament; a person may make an image, no, he should. (Zinzendorf 81)

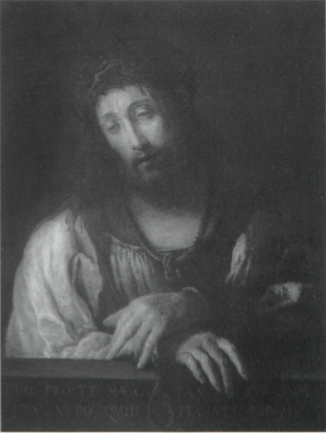

Zinzendorf preached this anti-iconoclastic sermon at Fetter Lane to counter the hostile attacks of Dissenting and Methodist critics, who claimed that Moravian artistic practices were crypto-Papist. Thus, he recounted his life-changing experience in which art first opened his heart (Herz-Lev). During his student travels, he visited a gallery in Düsseldorf, which featured Domenico Feti’s Ecce Homo, a poignant painting of Jesus’s suffering under the crown of thorns before his crucifixion. Under the wounded body scrolled a Latin caption: “All this I have suffered for you, but what have you done for me?” (Atwood, Community 97) (illus. 1). An emotional Zinzendorf recalled that “My blood rushed because I was not able to give much of an answer, and I prayed to my Saviour to make me ride in the comradeship of his suffering with force.” The rushing blood, yearning for forced intimacy, comradeship in suffering—religious passions stimulated by a work of art—intensified the young nobleman’s determination to serve Jesus and to identify with his fully humanized nature, which he came to believe included not only suffering but sexuality. An admirer of Catholic doctrines of confession and forgiveness of sins, he hoped to utilize Catholic artistic traditions to invigorate the ecumenical Herzensreligion.

What made his commitment to religious art so creative and controversial was his injection of Kabbalistic concepts of sacramental

In the process, Zinzendorf revived the Renaissance artistic tradition that linked the ostentatio vulnerum (showing forth of the wounds) with the ostentatio genitalium (showing forth of the genitals), a linkage which stressed the full “humanation” of Jesus (Steinberg 3, 16, 18, 57, 83, 373). In 1750 the count predicted that “one of these days” artists will portray the crucified Jesus in a new way, fully nude without a cloth covering his sexual organs; his genitals will again express “his honor and innocence,” for “he is no fallen Adam” (Peucker, “Kreuzbilder” 137).11↤ 11. I am grateful to Paul Peucker, Moravian archivist formerly at Herrnhut and now at Bethlehem, PA, for sending me this important article and for help with identifications. Though no records of such paintings survive, the portrayals may have been used more privately, within Zinzendorf’s family and inner circle, for in 1748 his niece, Sophie Reuss, made a miniature drawing of a nude Christ on the cross, with no covering cloth and with blood flowing profusely from his five wounds. This religiousartistic belief perhaps found an echo in Blake’s affirmation, “The head Sublime, the heart Pathos, the genitals Beauty, the hands & feet Proportion” (E 37).

As a highly educated and basically skeptical intellectual, Zinzendorf spoke about his own struggle to move beyond speculative abstraction to imaginative visualization. He granted that the capacity for vision—“that extraordinary state” when one is “in the Spirit”—was not equally shared by every Brother and Sister:

This may happen with more or less sense experience, with more or less distinctness, with more or less visibility, and with as many kinds of modifications as the different human temperaments and natural constitutions can allow in one combination or another. One person attains to it more incontestably and powerfully, the other more gently and mildly; but in one moment both attain to this, that in reality and truth one has the Creator of all things . . . standing . . . in the form of one atoning for the whole human race—this individual object stands before the vision of one’s heart, before the eyes of one’s spirit, before one’s inward man. (Zinzendorf 82-83)One should be able to say, “I see him as clearly as if he were here; I could paint him right now,” for then “He remains engraved in one’s heart. One has a copy of this deeply impressed there; one lives in it, is changed into the same image” (Zinzendorf 84-85). By focusing intensely and reverently on Jesus’s body and the intercourse between phallic spear and vaginal wound, the Moravian devotee could achieve a state of trance, of psychosexual euphoria, in which he or she “shook with love’s fever” and experienced the “mystical marriage” (Atwood, Community 219).

To increase the congregation’s capacity to “see,” “paint,” and “engrave,” Zinzendorf recruited and commissioned artists to create vivid portrayals of Christ’s life and sufferings for the Brothers and Sisters to study while powerful hymns, guitars, violins, and trombones provided background music. At the chapel in Fetter Lane and at Lindsey House in Chelsea (the count’s headquarters), the whitewashed walls were covered with paintings of biblical and allegorical scenes, as well as portrayals of Moravian history and international missionary work. Adding to the mystical atmosphere were watercolored transparencies, through which lanterns and candles projected luminous visions into the congregation rooms. Given the often bloody and sometimes sensual symbolism of the paintings and hymns, these scenes would provoke much controversy and hostile attacks from critics. However, the passionate letter of Catherine Armitage, which reveals her deep immersion in the spiritual-erotic themes of the Sifting Time, suggests that Blake’s mother responded positively to the Moravians’ stress on the role of art and music in the development of visionary spirituality.12↤ 12. Moravian Archive: C/36/2/159. As she encouraged the artistic productions of her imaginative son, she was perhaps implementing Zinzendorf’s peculiar but progressive notions of “infant education.”

Zinzendorf admired the “pansophic” educational theories of Comenius, whose portrait was displayed at Lindsey House, and he implemented them in his voluminous sermons, songs, and lessons for children (Meyer 94-105). Comenius stressed the innocence of childhood, the importance of parental affection, the healthy effects of outdoor free play, and, most importantly, the use of pictorial images to inculcate religious sentiments. What was surprisingly modern or Freudian in the count’s pedagogy was his belief that even embryos and infants were receptive to his sex, blood, and wounds theology and that “the process of religious education and socialization began in utero” (Atwood, Community 178-83; “Blood” 192-93). Within the “embryo choir,” the pregnant mother was pampered and counselled; after birth, she and her infant became part of the “suckling choir,” and joyous love feasts were held for them. In order to sensate the “assembled image” of the God-Man in one’s heart, mother and child must “view, picture, and meditate about the saviour from head to foot.” These injunctions were sung by the mother in the home and by the children in catechistical hymns. In a Moravian drawing from 1754, Zinzendorf’s two-year-old daughter is shown meditating upon a painting of the crucified Jesus (Peucker, “Kreuzbilder” 170).13↤ 13. Because Elizabeth von Zinzendorf was born in 1740, the 1754 portrayal probably had a pedagogical purpose for current infant education.

Zinzendorf was evidently familiar with sixteenth-century paintings that portrayed the infant Christ with an erect penis and giving a flirtatious “chin-chuck” to his adoring mother, and there were hints of such themes in his lyrics for children.14↤ 14. The occasional erection of the infant penis is a normal and natural phenomenon, but many Renaissance artists stressed it as proof of the full “humanation” of Jesus. Steinberg (3, 10, 76-79 and plates 83-88) gives examples such as Alvise Vivarini’s Madonna and Child with Saints (c. 1500), Perino del Vaga’s Holy Family (c. 1520), Perugino’s Madonna and Child (c. 1500), Correggio’s Madonna of the Basket (c. 1523-25), etc. When Blake wrote his provocative “Cradle Song,” he seemed to draw on the Moravians’ maternal and infant sexual psychology. begin page 88 | ↑ back to top In Blake’s song, the mother strokes the soft limbs, the babe’s face and heart respond with smiles and peaceful beat, and she recognizes the erotic pleasure stimulated in the infant:

Sweet Babe in thy face

Soft desires I can trace

Secret joys & secret smiles

[Such as burning youth beguiles del.] (E 468, 852)

Though Blake deleted the last line, he went even further in his paean to free love, Visions of the Daughters of Albion, where Oothoon proclaims:

Take thy bliss O Man!Blake’s “laps of pleasure” takes on a new connotation when placed in a context of Zinzendorf’s pedagogical instruction that the school of the female Holy Spirit was “a family school, that is, a school on the lap, in the arms of the eternal Mother.” In German, the same word (Schoss) is used for lap and womb, and the mother’s “school” for her infant took on a spiritualerotic connotation, which was vividly expressed in hymns for the embryo and suckling choirs. Blake’s lustful, nestling infant recalls the sung injunction to each mother, “That your child lay naked and bare on your lap” (Atwood, Community 178-79). Following Comenius’s teaching, the Moravians advocated maternal breast feeding rather than farming infants out to wet nurses. Blake’s mother may well have heard Peter Boehler’s talks to the married Sisters, when he stressed that “suckling” must be done with “gracious ideas as a Divine Worship.”15↤ 15. Moravian Archive: C/36/7/3 (28 May 1749). Boehler was the main “marriage counsellor” for the Brothers and Sisters, and he spoke frankly about intercourse, orgasm, conception, etc., in a surprisingly modern way. Decades later, Blake would lament that so many selfish parents reject this beneficial practice: “The child springs from the womb . . . / The young bosom is cold for lack of mother’s nourishment, & milk / Is cut off from the weeping mouth” (E 285).

And sweet shall be thy taste & sweet thy infant joys renew!

Infancy, fearless, lustful, happy! nestling for delight

In laps of pleasure .... (E 49)

Determined to make the sensating of Jesus a joyous experience, Zinzendorf advocated that parents and children—of every age, class, and background—should participate in a rich Renaissance-Baroque culture of painting, poetry, and music. Remembering his own unhappy childhood, when he was sent away to boarding school and instructed by puritanical pedants, he urged the Moravians to home-school their children. Preaching at Fetter Lane in 1753, he instructed the parents to build a home “for a Christian family life which will make possible the ideal church in the home with proper religious training of children”; moreover, “parental training is the natural method as compared with institutional training which is artificial” (Meyer 138, 142). Unusually for the time, he believed that an affectionate mother was the best teacher for a young child, and that she should inculcate a love of art and music to stir the visionary senses of the Herz-Lev.

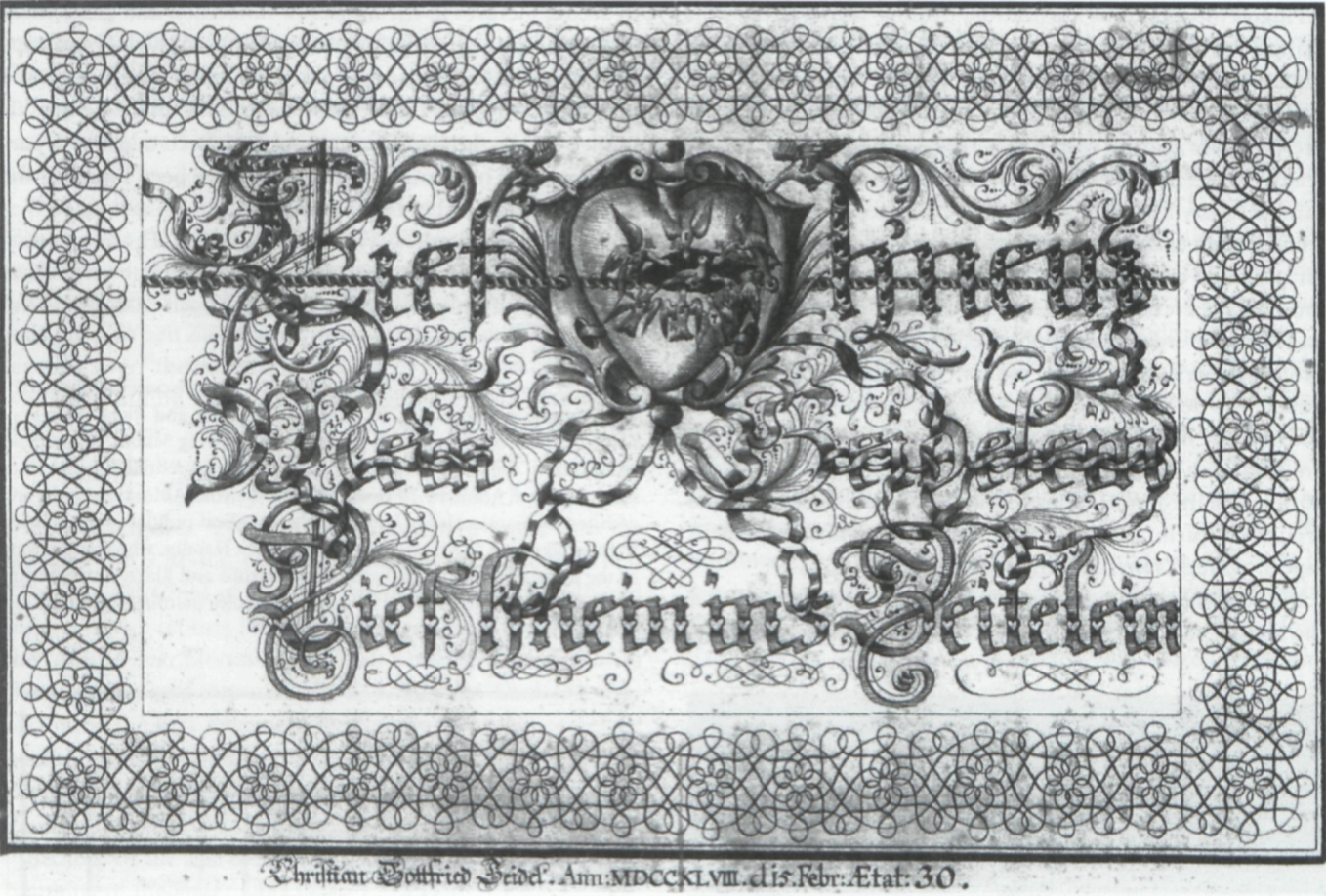

From infancy on, a Moravian child was exposed to religious art and script, including the German artistic technique of Frakturschriften, the ornamental breaking or fracturing of letters, which Zinzendorf and Boehler had observed when they visited the Boehmenist-Rosicrucian community at Ephrata, Pennsylvania (Sachse 1: 354-64, 401-02). In the Ephratans’ mystical calligraphy, the scribe represented the breaking of the artist’s self-will and opening to union with Christ by breaking the letters and surrounding them with swirling ornamentation, which created the “sprouting of a florid paradise” (Bach 182-84). The “illuminations” were usually “drawn with pen and ink, and then embellished with vigorous colors.” The actual practice of Fraktur, with its intense concentration and visualization, could produce mystical states, for “each scribe has the birthing process in himself after rebirth.” In the magnificently illuminated Ephrata ABC book, Sisters Anastasia and Efigenia drew capital letters

constructed with a series of swinging, voluptuous curves, all interstices of the letters filled with additional scrollings and floral forms. A passionate devotion to the work caused the individual calligrapher to further elaborate all possible areas with minute stipplings and dottings, in the manner of steel engraving. Significant symbolistic motifs also entered into the enrichment of the capitals. (Frances Lichten, quoted in Alderfer 125-26)Alderfer adds that

some of them, such as the A and the O, make use of the human form to portray a provocative symbolism. . . . The O suggests Anastasia’s vision of Beissel [the community leader] being crowned with the Holy Spirit . . .; it may also reflect her sublimated love for him. . . . The borders are astonishing .... (126) (illus. 3)

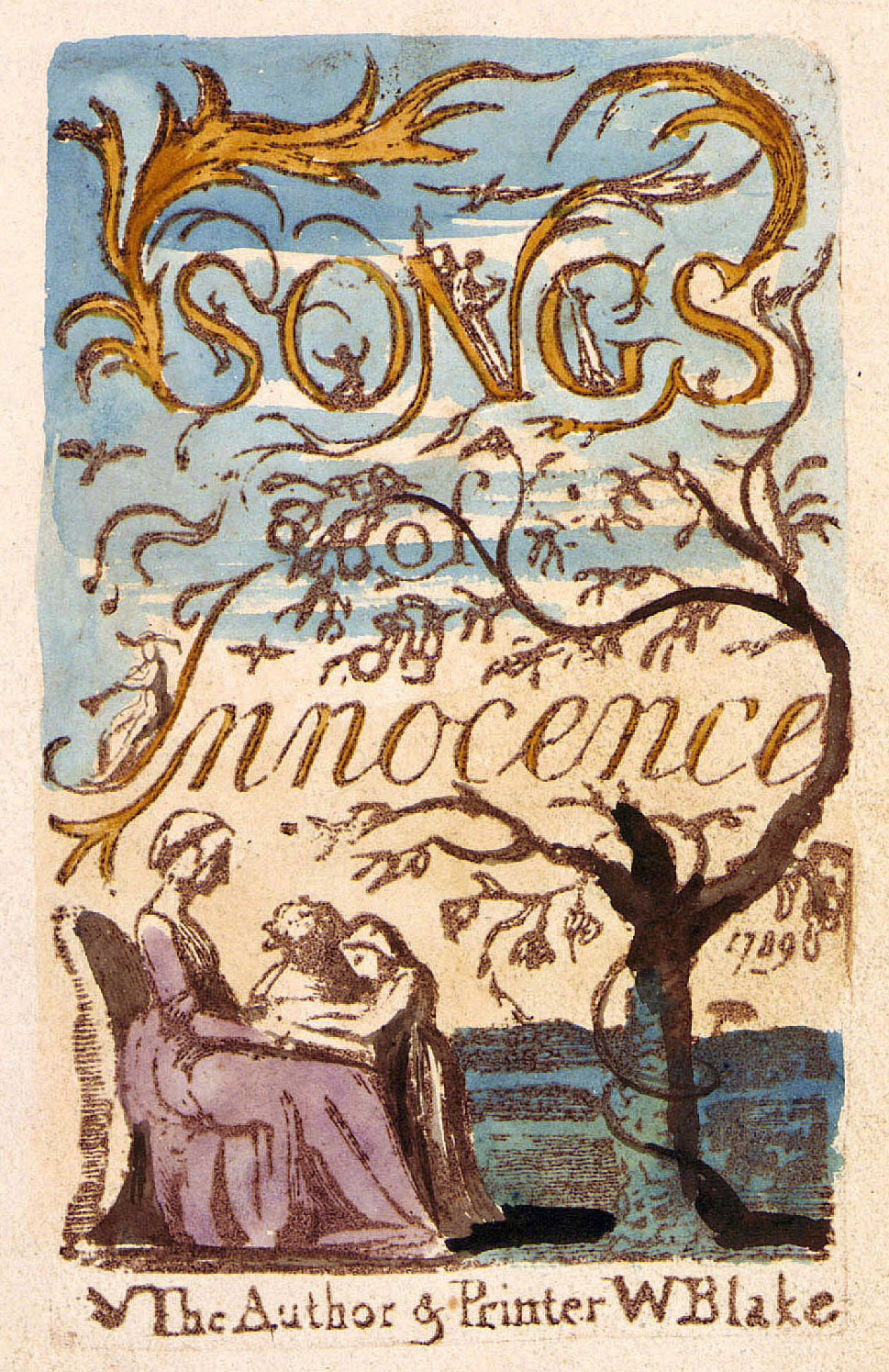

Despite their opposition to the Ephratans’ policy of celibacy (they believed that earthly marriage would prevent divine marriage with Sophia), the Moravians borrowed liberally from the sect’s mystical art and symbolism (Stoudt 94-96). Like Conrad Beissel, Zinzendorf believed that “art, literature, and music were not [to be] regarded as separate disciplines; they united in one common spiritual experience” (Alderfer 125). Thus, a comment by the Pennsylvanian art historian John Stoudt becomes suggestive; referring to the Ephrata ABC book, he observes that the frontispiece “is a drawing much like those of William Blake” (Stoudt 138) (illus. 4 and 5). At this time in London, the walls at Fetter Lane and Lindsey House were hung with papers and canvases of Moravian poetry and hymns, ornamented with painted letters (often in elaborate German Gothic script), whose twisting and curving gave them “a florid quality” (Podmore 133, 151-52; Atwood, begin page 89 | ↑ back to top “Blood” 171) (illus. 6). Paintings and drawings were often surrounded with Spruchbänder, sayings or aphorisms that illustrated the text (Peucker, “Kreuzbilder” 166). Catherine Armitage Blake would have seen these elaborate and charming “illuminations,” which also decorated private rooms. The Moravians’ love of religious art provoked iconoclastic Dissenters to criticize “our innocent pictures and crucifixes in

At Fetter Lane, Catherine Armitage was also exposed to the Jesuit emblem tradition of “iconomysticism.” Thomas Armitage had written his application letter to John Cennick, a begin page 90 | ↑ back to top

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

Cennick, who greatly admired the Moravian paintings and engravings he observed in Germany and England, would have recognized the relevance of Jesuit emblematic techniques to Zinzendorf’s artistic-pedagogic goals. As Praz observes, the “didactic properties” of emblems were “calculated to further the Ignatian technique of the application of the senses, to help the imagination to picture to itself in the minutest detail circumstances of religious import”:

They made the supernatural accessible to all by materializing it. Rather than mortifying the senses in order to concentrate all energies in an ineffable tension of the spirit, according to the purgative way of the mystics, the Jesuits wanted every sense to be keyed up to the pitch of its capacity, so as to conspire together to create a psychological state pliant to the command of God. (Praz 1: 156)Similarly, Moravian artists were instructed to arouse and utilize all the senses, so the viewer would move beyond mere understanding and would fully participate in, fully sensate, Jesus’s experiences from crucifixion to resurrection (Peucker, “Kreuzbilder” 169).

The fine engravings in Pia Desideria, by Boëce van Bolsvert, drew on the Jesuits’ spiritual-sensual interpretation of the techniques of engraving. As Praz observes, begin page 91 | ↑ back to top

The fixity of the emblematic picture was infinitely suggestive; the beholder little by little let his imagination be eaten into as a plate is by an acid. The picture eventually became animated with an intense, hallucinatory life, independent of the page. The eyes were not alone in perceiving it; the depicted objects were invested with body, scent, and sound .... (Praz 1: 156)

In Blake’s Marriage of Heaven and Hell, he employed a similar engraving metaphor of acid eating into plate. He may also have drawn on the Moravians’ iconomystical and antinomian sense of erotic visualization, which reversed the orthodox Christian denigration of the senses and sexuality:

. . . the whole creation will be consumed, and appear infinite, and holy whereas it now appears finite & corrupt.

This will come to pass by an improvement of sensual enjoyment.

But first the notion that man has a body distinct from his soul, is to be expunged; this I shall do, by printing in the infernal method, by corrosives, which in Hell are salutary and medicinal, melting apparent surfaces away, and displaying the infinite which is hid.

If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is: infinite. (E 39)

Praz’s description of iconomysticism reveals why it was such an effective vehicle for Moravian concepts of the mystical marriage, for this Jesuit “cult was wonderfully suited to a society accustomed to picture human love under the guise of the Alexandrian Eros” (1: 132). Hugo’s great popularity arose from his use of the Song of Solomon and the Psalms,

texts whose metaphors inevitably suggested emblems with the Oriental lusciousness of their appeal to the senses. Tears and sighs, . . . voluptuous swoonings and sweet and subtle pains, what a part they play in the Pia Desideria! In a nocturnal garden, heavy with perfume, Anima feels her knees give way under her, . . . while from her bared breast burning ejaculations Ah! Utinam! Heu! shoot like arrows towards the ears of God. . . . Suddenly the garden is all a-bubble with springs. . . . Love darts from his mouth a quivering tongue of flame, and, caressed by that heat, Anima exudes huge drops from head to foot. . . . What wild races through that nocturnal garden heavy with perfumes! (Praz 1: 133-34)Zinzendorf similarly compared the Moravians’ visualization of Christ to the bride’s in the Song of Songs. Quoting the lines “This is my beloved,” he stressed that her lover is actually Christ, and “there He is painted piece by piece” (Zinzendorf 81). In May 1749 at Fetter Lane, his birthday was celebrated with “illuminated Pictures” which showed “Fountains springing” and the count “solacing himself in a Garden where the Fountains spouted Blood” (Stead 300). begin page 92 | ↑ back to top

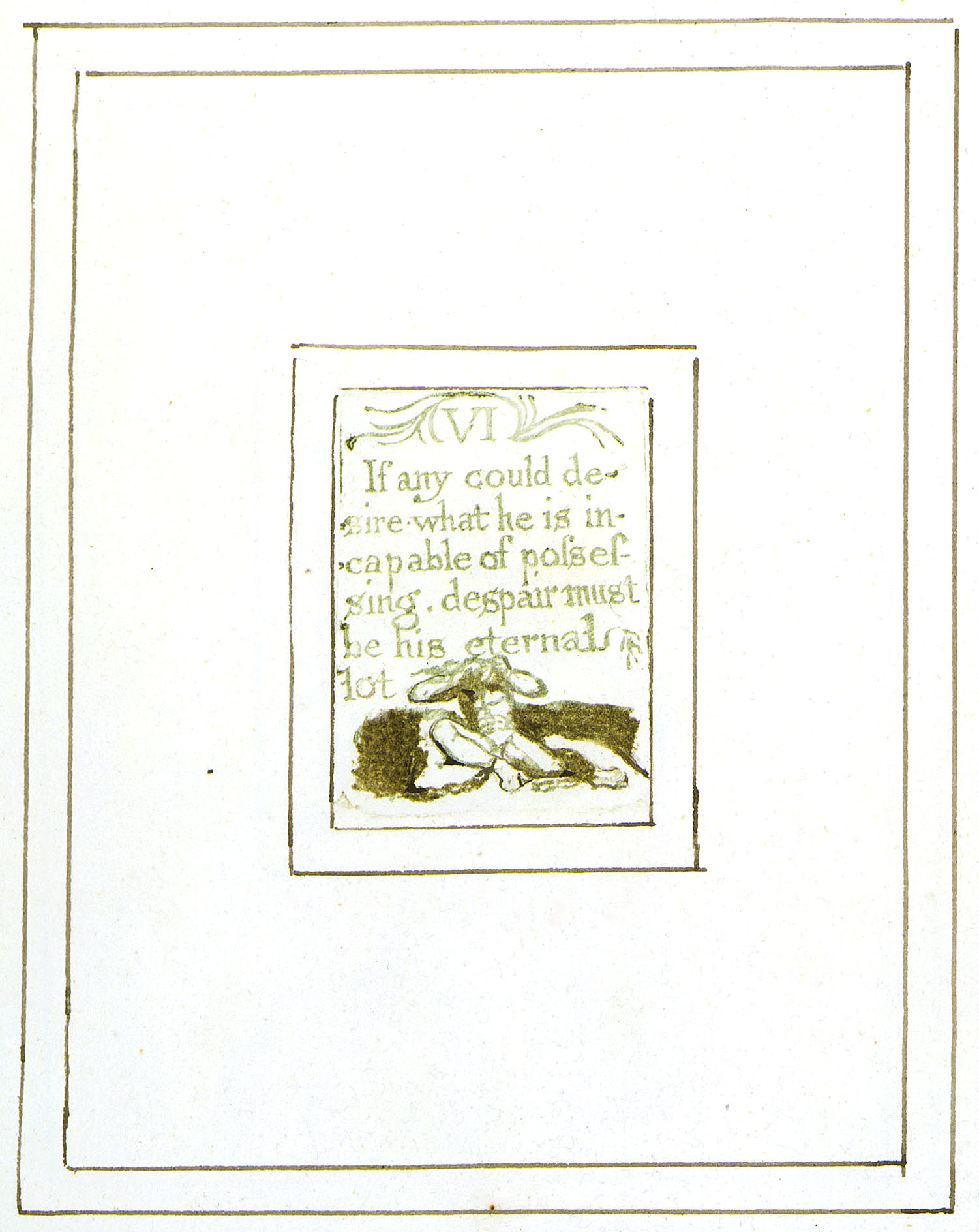

Hugo’s most famous illustration, “Anima Trying to Soar on Wings, but Held Back by a Weight Tied to Her Foot,” perhaps finds an echo in Blake’s tiny emblem book, There is No Natural Religion (Hugo 334) (illus. 7). On the plate designated V, Blake drew a figure soaring with hands raised, while the inscription reads, “More! More! Is the cry of a mistaken soul, less than All cannot satisfy Man” (E 31). On the plate headed VI, he drew a naked man chained and fettered by his ankles, with the text, “If any could desire what he is incapable of possessing, despair must be his eternal lot” (E 31) (illus. 8). Hugo’s Jesuit work had been expurgated and published in English translations by Protestant writers, such as Frances Quarles and Edmund Arwaker, who de-emphasized the pictorial “iconomysticism” and added more moralistic and puritanical literary comments (R. Freeman 114, 133, 140-42, 207). But for Cennick and Zinzendorf, it was the Jesuitic stress on intense visualization and the arousal of spiritualerotic desire that was the most important aspect of Hugo’s mystical emblems.

In 1806 Blake’s friend Benjamin Heath Malkin reported that the artist, “very early in life, had the ordinary opportunities

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

Having studied at Herrnhaag, the most radical center of Sifting Time theosophy, Müller was familiar with the daring experiments in sexual, ritual, poetic, and artistic innovation which occurred there (and which led to the Moravians’ expulsion).19↤ 19. On the “poetic world” of “spiritualized sexuality” at Herrnhaag, see Erbe. The radical leader of the “youth movement” at Herrnhaag was Zinzendorf’s charismatic son, Christian Renatus, who in 1749 moved to London, where he was revered by the Fetter Lane congregation, who considered his death in 1752 at age twenty-four a great tragedy. When Zinzendorf moved to London in 1749, Müller took over “the oeconomical Care of Bloomsbury-House,” while continuing his artistic and engraving work. According to his obituary, “The last Piece of Work he did in his own Art, (wherein he was very ingenious) was ingraving a small Picture of the Ordinary [Zinzendorf].” Having become sick with “a malignant fever,” Müller “was kissed home into the Sidehole” on 9 March 1751, apparently at the same time that “Thomas, the Child of Br + Sisr Armitage” died. Their shared funeral notice reports that the Armitage child “was buried in the Ground near Bloomsbury,” while Müller was carried from Bloomsbury “and deposited in the Earth at Chelsea,” thus becoming the first interment in the new Moravian cemetery. According to the German church historian Kai Dose, who is researching Müller’s life, he was a talented artist whose surviving portraits and engravings are worth renewed interest.20↤ 20. Another Moravian artist, Johann Jakob Müller, spent a brief period in London in the 1740s, where he opposed “daubers of reason” and “naturalists”; he then moved to Herrnhut, where he became “director of the Wound and Nailhole Painting Academy” (Peucker, “Painter”).

Because of the sale of Lindsey House in 1774 and the Nazi bombing of the Fetter Lane Chapel in 1941, the great Zinzendorfian collection of paintings and engravings was dispersed or destroyed (Kroyer 50-63). However, from pre-1941 descriptions and surviving paintings at the Brethren’s other centers, we can learn more about the Moravian artists who moved in the Armitage-Blake milieu in the 1750s and 60s. More famous than Müller was Abraham Louis Brandt (1717-97), a talented Franco-Swiss engraver and painter (“Brandt”; “Lebenslauf”). He was the brother of Louise Hutton, who had earlier been a member of the “French Prophets” before marrying the English minister James Hutton and converting to Moravianism (Benham 95, 194-96, 375). She shared with her brother an interest in Boehmenist and mystical writers, and he expressed these themes in the religious paintings he produced for Zinzendorf in England, before moving on to a Moravian community in Russia in 1764. Less famous was John Cooke, a Catholic artist from Leghorn (called “the Italian”), who acted as ship’s mate on Moravian voyages to America, where his joyous temperament, violin playing, and artistic productions made him a beloved visitor (Hamilton 171-72, Nelson et al. 19, 48). After participating in the Fetter Lane Society in the 1740s, Cooke moved on to the “Pilgrim Congregation” in Germany.21↤ 21. Moravian Archive: Box A2, Pilgrim House Diary (1743-48), p. 8; C/36/5/1, p. 4. Even more intriguing—and more relevant to Blake—was the Dantzig-born Johan Valentin Haidt (1700-80), whose significant role in the London art world is receiving new attention from scholars (Nelson, Haidt). As we shall see, a Moravian art historian suggests that Blake was influenced by one of Haidt’s paintings.

Originally apprenticed as a goldsmith, the young Haidt determined to follow his real love, religious and historical painting. After traveling through Europe to study the Old Masters, he moved to London in 1724, married a Huguenot woman, and, while practising his craft, opened an “academy” in his home, where he and his students studied “live nudes.” His comment about the importance of the nude model “may be the earliest such reference in English art” (Nelson, “Haidt’s Theory”). He eventually befriended George Michael Moser (1704-83), a Swiss-born gold-chaser, who shared his yearning to participate in higher art. The two men “seemed to have started a predecessor to the Royal Academy of Arts in Haidt’s house,” which influenced Moser’s later role as a founding member of the Royal Academy. When William Blake applied to study at the Royal Academy in 1779, it would be Moser, “the venerable Keeper,” who evaluated his work and oversaw his subsequent studies (Bentley, Stranger 49-51). However, it was Haidt’s role as a Moravian artist—known as “the painting Preacher”—which is most suggestive when exploring the Blake family’s attitudes towards art.

Attracted by the passionate preaching he heard at Fetter Lane in 1738-39, Haidt experienced a “heart-warming” similar to that of John Wesley, who was intensely attracted to the Moravians at that time. In 1740 Haidt traveled to Herrnhaag, where he achieved “a mystical experience which he remembered all his life” (Nelson, Haidt 9-13). Though Wesley had been rejected by the Germans as a homo perturbatus, Haidt was eventually accepted into the congregation. Moving between Germany and England, he began the painting of large symbolic works with life-size figures, sometimes influenced by the Jews he observed at Moravian services. Deeply infused with the “blood and wounds” theosophy, Haidt’s emphasis on the role of art in the spiritual development of children inspired much of the creative and imaginative teaching in Moravian families. Catherine Armitage could have heard about Haidt’s impressive paintings from John Cennick, who studied and admired those exhibited in Moravian halls in Germany (Peucker, “Kreuzbilder” 138). In 1749, when Zinzendorf moved to London, he commissioned Haidt to paint dozens of portrayals of events in Jesus’s life and in Moravian history, to be displayed begin page 94 | ↑ back to top

According to Haidt, young students should first master drawing with a firm outline before attempting painting, and they should study classical sculpture and copper engravings of the Old Masters. Though Blake’s mother is credited as the primary inspiration for his artistic interests, his father eventually supported William’s artistic bent: “The love of designing and sketching grew upon him, and he desired anxiously to be an artist” (Cunningham, in Bentley, BR[2] 628). James Blake began to encourage William’s drawing, bought plaster casts of classical sculpture, and funded his purchases of engravings of Old Masters. Possibly more important for James, who initially intended his son for the hosier’s shop, was Haidt’s insistence on the importance of an independent religious spirit in the young artist, for talent “is a gift from God, and whoever is sure of that and convinced of it, he can paint.” Moreover, “each one knows best what his inclinations are, and he should follow them.” Zinzendorf preached and Haidt taught that engraving was a form of “high art,” which required sophisticated and erudite training in order to capture the soul and beauty of drawings and paintings. It also had a spiritual resonance, for the image of Jesus should be engraved in one’s Herz/Lev. When the adolescent Blake, with his parents’ blessing, decided to apprentice himself as an engraver, he may have absorbed such lofty ambitions for his craft.

Haidt shared Zinzendorf’s reverence for Mary Magdalene, and they maintained the medieval tradition that she was a prostitute and adulteress, until Jesus cast out the seven devils, who plagued her with illicit erotic desires. They also seemed familiar with a controversial theme in that tradition—i.e., “all things that she had willingly done before in the service of the flesh she now in sorrow turned to the service of her Lord” (Phipps 139). At Fetter Lane, Zinzendorf preached that Christ begin page 95 | ↑ back to top

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

Given this context, Haidt’s painting The Crucifixion seems to express Zinzendorf’s version of the Jesus-Magdalene relationship, for he portrayed her sensuously with long yellow hair and emotionally attached to Jesus. Vernon Nelson, who was unaware of the Moravian association of Blake’s mother, observes that in Haidt’s painting “the pose of the soldiers gambling for Jesus’ cloak should be compared to that in Blake’s portrayal of the Crucifixion” (Nelson, Haidt 21; Butlin #495) (illus. 9 and 10).23↤ 23. Unfortunately, the photo in Nelson’s Haidt is misnumbered, for the description of plate 35 should refer to a painting which includes the gambling soldiers (not reproduced in the catalogue), which is owned by the Moravian Historical Society in Nazareth, PA. I am grateful to the archivist, Mark Turdo, for sending me a photo of the correct picture. Nelson points out that in another Haidt painting, At the Foot of the Cross, the Magdalene kisses Jesus’s feet, thus revealing the artist’s immersion in the Sifting Time ethos, with its eroticization of spiritual relationships (Nelson, Haidt 21) (illus. 11).24↤ 24. For other Moravian paintings of Mary Magdalene kissing and embracing Jesus’s feet, see Peucker, “Kreuzbilder” 135, 142. In Blake’s picture Mary Magdalene Washing Christ’s Feet, she is actually kissing his feet (Butlin #488) (illus. 12); Martin Butlin notes that in Blake’s painting, Christ the Mediator: Christ Pleading before the Father for St. Mary Magdalene, the subject is not biblical but possibly from John Bunyan; however, “the apparent application of the theme to the Magdalene is Blake’s own” (Butlin #429). It is suggestive that Blake produced these paintings during a period (c. 1800-07) of friendly contact with two liberal Moravians, the artist Jonathan Spilsbury and the poet James Montgomery, who both participated in services at Fetter Lane.25↤ 25. Blake possibly knew Spilsbury when both exhibited at the Royal Academy in the 1780s, and he described his conversation with the Moravian artist in 1804 (E 755). For Spilsbury’s career, see Young. On Blake’s association with Jonathan Spilsbury and its Moravian significance, see Keri Davies, “Jonathan Spilsbury and the Lost Moravian History of William Blake’s Family” [in this issue—Eds.]. Blake may have met Montgomery during the radical writer’s visits to the London Corresponding Society in the 1790s. Though we have no definite evidence for their acquaintance, Bentley notes that Robert Cromek’s letter to Montgomery in 1807 “suggests a connexion between Blake and James Montgomery” and “implies an easy and personal contact between the two men”; see BR(2) 234-35, 262, 277. For Montgomery’s career and Moravian association, see Montgomery, Memoirs and Everett. I provide more information on the Oriental interests of Spilsbury, Montgomery, and Blake in Why Mrs. Blake Cried 322-29. Could they have taken Blake to his mother’s former church, where Haidt’s paintings were still exhibited?26↤ 26. The striking similarities between Blake’s “tempera series” of “the Life of Christ” for Thomas Butts and the surviving description of Haidt’s thirty-four paintings of the “sacramentlichen Handlungen des Heylands” (Jesus’s life-story from conception to resurrection) is worth further study. Haidt’s series was discussed and commissioned at “a conference in Bloomsbury, 2 October 1749,” when Blake’s mother was a participant in Moravian affairs. After the sale of Lindsey House in 1774, many of these paintings were moved to the Fetter Lane Chapel, where they survived until the 1941 bombing. See Peucker, “Kreuzbilder” 172-73; Kroyer 52; Bindman 121-31.

begin page 96 | ↑ back to topRecent biographers of the engraver and caricaturist James Gillray (1756-1815), who was raised and educated as a Moravian, have inaccurately characterized the Unitas Fratrum as “an austere and unattractive religious sect,” who “deplored all joy and pleasure” and who provided children with a “grim” upbringing (Godfrey and Hallett 12). However, Moravian notions of child rearing were actually and unusually benevolent. In 1766, when the Moravian minister James Hutton was questioned by Lord Shelburne—“Pray, how do your children go on? Do they take after their parents?”—he answered emphatically, “Yes, God be praised!” Hutton then described the Moravian pedagogical methods with children:

Ingenuous and affectionate treatment, without force and violence, we find has a blessed effect on their education. We once thought otherwise; but we succeeded better by gentleness. We do all we can to prevent that servile imitation and hypocrisy which severity always or, at least, is most likely, to produce. O! My Lord, could you but see the heartiness of our children, you would be touched. (Benham 417)

As she home-schooled her children, Blake’s mother seems to have adopted this notion of educational “gentleness,” for she was “a tender and sympathetic mother, more inclined to overlook faults than to punish them” (Bentley, Stranger 5). For Moravians, the “heartiness” of their children was a resonant, multileveled quality; Herzlichkeit meant passionate, enthusiastic, and imaginative visualization of and engagement with the body of the God-Man. Unaware of the erotic-artistic emphasis of Zinzendorf’s pedagogy, the Gillray scholar Draper Hill lamented that “at the threshold of understanding,” Moravian four-year-olds “were pushed to terrifying heights of introspection” (Hill 8). But it was more the terribilità of Michelangelo (who was revered by Zinzendorf and his artists); it was a transforming, energizing, imaginative passion to which the children were “pushed.” When Isaac Disraeli later observed that “Blake often breaks into the ‘terribil via’ of Michael Angelo,” he meant terribilità (Bentley, BR[2] 329fn).

The Moravian-educated poet and art critic, James Montgomery, attributed his own youthful “heartiness” to the vivid paintings begin page 97 | ↑ back to top and powerful music he studied at the Moravian school in Fulneck, Yorkshire, in 1777-87, while his missionary parents served (and died) in the West Indies. The schoolboys assembled and stood for a few minutes in front of “a superb painting of a dead Christ,” rendered more dramatic by the illuminating rays of a strategically placed lantern (Montgomery, Memoirs 1: 31, 59). In his dormitory, Montgomery meditated upon a “huge painting of the Entombment of Christ, by the old Moravian

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

There is no system of religion, which I have yet seen, which, taking all in all, has half the charm for a young, a warm, and a feeling heart, as that professed by these people. I once believed; I once enjoyed its blessings; I once was happy! . . . The hymns of the Moravians are full of ardent expressions, tender complaints, and animated prayers; these were my delight. As soon as I could write and spell, I imitated them, and before I was thirteen I had filled a little volume with sacred poems. (Montgomery, Memoirs 1: 46)

Was it a similar early influence that inspired the adolescent Blake to write poems of spiritual[e] and romantic yearning? Bentley notes that in Blake’s precocious love poems, the “sexual suggestiveness is astonishing” (BR[2] 260-61). The adult Montgomery was an early admirer of Blake’s “wild & wonderful genius,” especially in his illustrations to Blair’s The Grave (1808), which critics scorned for their “libidinous” combination of carnality with spirituality (Bentley, BR[2] 260-61; Essick and Paley 23-25). Montgomery probably knew that Zinzendorf had also been criticized for expressing a “Fleischlische Spiritualität” (fleshly spirituality) (Deghaye 167n41). Blake, in turn, praised Montgomery’s publication, The Wanderer of Switzerland, and Other Poems (1806), assuring him that it will command the applause of “all Lovers of the Higher Kinds of Poetry” (Bentley, BR[2] 236). In this volume, Montgomery praised the Moravians’ renewed missionary and abolitionist efforts, and he made a provocatively Blakean allusion to the “Daughters of Albion,” whom he exhorted to “Weep!” (in his autobiographical account of a frustrated, youthful love affair) (Montgomery, Wanderer 11, 167, 135, 147).

Fortunately, a new generation of Moravian scholars is lifting up the blanket of darkness that was thrown over the Sifting Time by conservative church historians after Zinzendorfs death in 1760.27↤ 27. Vernon Nelson began the recovery of Haidt’s artistic career, while the revisionist works of Colin Podmore, Craig Atwood, and Paul Peucker shed new light on the theology and art of the Sifting Time. Christiane Dithmar contributes important new Jewish material relevant to the psychoerotic themes of the “mystical marriage.” As they shed new light on the historical realities of that fascinating and controversial period, they make it possible to uncover the equally suppressed artistic history of the Sifting Time, whose painters, engravers, and poets may have influenced Catherine Armitage Blake and her visionary son William. Thus, it will be fitting to conclude with a tribute to Blake’s mother by quoting lines from a Moravian hymn, the “Te Matrem,” which Zinzendorf believed was especially effective at instilling “heartiness” in children.28↤ 28. For the once central but then censored role of the “Te Matrem” hymn, see Atwood, “Mother.” Praising the creative and inspirational power of the Divine Mother, wife of God and mother of the God-Man, the congregation joyfully sang to “Thee, that Mother of Christ his Bride”:

Thou didst inspire the Martyrs tongues,

In the last Gasp to raise their songs,

Thou dost impel the four Zoa,

Who singing rest not night nor day . . .

Thou Mother of God’s Children all,

Thou Sapience archetypal! . . .

That thou the Prophets dost ordain,

And gifts and wonders to them deign.

(Collection of Hymns 2: 297-98)

In 1797 Blake gave the title Vala to his visionary, prophetic epic, which begins with the words, “The Song of the Aged Mother,” whose verses herald “the day of Intellectual Battle”:

Four Mighty Ones are in every Man; a Perfect UnityAround 1807, at a time of friendly Moravian contacts, he changed the title to The Four Zoas, and “those Living Creatures” (zoa, Greek plural) subsequently became “the Four Eternal Senses of Man”—senses contained within the earthly man and the God-Man (Albion) (Bentley, Stranger 198, 310). Did Blake remember the reference to “the four Zoa” in the Moravian hymn to the Divine Mother, while he revised his phantasmagoric tale of psychoerotic disintegration and reintegration within the human and divine worlds?29↤ 29. Justin Van Kleeck points to the previously unnoticed apostrophe between the “a” and “s” of the “Zoas” (i.e., “Zoa’s”) on Blake’s title page (Van Kleeck 39). This may reflect a mnemonic slip from the “four Zoa” of the Moravian hymn, or his uncertainty about how to anglicize the Greek plural. This and similar questions, provoked by ongoing discoveries in the international archives of the Unitas Fratrum, suggest that new answers and new perspectives will emerge, as we continue to explore the esoteric, erotic, and artistic underworld of Moravian “heartiness” and terribilità. begin page 99 | ↑ back to top

Cannot Exist. but from the Universal Brotherhood of Eden

The Universal Man. To Whom be Glory Evermore Amen

(E 300)

Works Cited

Alderfer, Everett Gordon. The Ephrata Commune: An Early American Counterculture. Pittsburgh: U of Pittsburgh P, 1985.

Atwood, Craig. “Blood, Sex, and Death: Life and Liturgy in Zinzendorf’s Bethlehem.” Diss. Princeton Theological Seminary, 1995.

—. Community of the Cross: Moravian Piety in Colonial Bethlehem. University Park: Pennsylvania State UP, 2004.

—. “The Mother of God’s People: The Adoration of the Holy Spirit in the Eighteenth-Century Brüdergemeine.” Church History 68 (1999): 886-909.

—. “Sleeping in the Arms of Jesus: Sanctifying Sexuality in the Eighteenth-Century Moravian Church.” Journal of the History of Sexuality 8 (1997): 25-51.

Atwood, Craig, and Peter Vogt, eds. The Distinctiveness of Moravian Culture: Essays and Documents in Moravian History in Honor of Vernon H. Nelson on His Seventieth Birthday. Nazareth: Moravian Historical Society, 2003.

Bach, Jeff. Voices of the Turtledoves: The Sacred World of Ephrata. University Park: Pennsylvania State UP, 2003.

Benham, Daniel. Memoirs of James Hutton. London: Hamilton, Adams & Co., 1856.

Bentley, G. E., Jr. Blake Records. 2nd ed. New Haven: Yale UP, 2004. Cited as BR(2).

—. The Stranger from Paradise: A Biography of William Blake. New Haven: Yale UP, 2001.

Bindman, David. Blake as an Artist. Oxford: Phaidon, 1977.

“Brandt, Abraham Ludwig.” Saur Allgemeines Künstlerlexikon. München: K. G. Saur, 1996. 13: 632.

Butlin, Martin. The Paintings and Drawings of William Blake. 2 vols. New Haven: Yale UP, 1981.

Cennick, John. The Life of Mr. John Cennick. 2nd ed. Bristol: Printed for the Author, 1745.

A Collection of Hymns of the Children of God in All Ages . . . Designed Chiefly for the Use of the Congregations in Union with the Brethren’s Church. London, 1754.

Davies, Keri, and Marsha Keith Schuchard. “Recovering the Lost Moravian History of William Blake’s Family.” Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly 38.1 (summer 2004): 36-43.

Deghaye, Pierre. La doctrine ésotérique de Zinzendorf. Paris: Klincksieck, 1969.

Dithmar, Christiane. Zinzendorfs nonkonformistische Haltung zum Judentum. Heidelberg: C. Winter, 2000.

Ellis, Samuel. Life, Times, and Character of James Montgomery. London: Jackson, Walford and Hodder, 1864.

Erbe, Hans-Walter. “Herrnhaag: Eine religiöse Kommunität im 18. Jahrhundert.” Unitas Fratrum 23/24 (1988): 13-224.

Erdman, David. The Illuminated Blake. London: Oxford UP, 1975.

Essick, Robert N., and Morton D. Paley. Robert Blair’s The Grave Illustrated by William Blake: A Study with Facsimile. London: Scolar P, 1982.

Freeman, Arthur. An Ecumenical Theology of the Heart: The Theology of Count Nicholas Ludwig von Zinzendorf. Bethlehem: Moravian Church in America, 1998.

Freeman, Rosemary. English Emblem Books. 1948. New York: Octagon, 1966.

Gilchrist, Alexander. Life of William Blake. 2 vols. Rev. ed. 1880. New York: Phaeton, 1969.

Godfrey, Richard, and Mark Hallett. James Gillray: The Art of Caricature. London: Tate Publishing, 2001.

Hamilton, Kenneth, ed. and trans. The Bethlehem Diary, Vol. I, 1742-1744. Bethlehem: Archives of the Moravian Church, 1971.

Hamlin, Talbot. Benjamin Henry Latrobe. New York: Oxford UP, 1955.

Hill, Draper. Fashionable Contrasts: Caricatures by James Gillray. London: Phaidon, 1966.

Hugo, Hermannus. Pia Desideria. 1624. Antwerp: Henry Aertssens, 1632.

[Hutton, James, ed.] A Collection of Hymns: Consisting Chiefly of Translations from the German, Part III. Hymnbook of the Moravian Brethren. 2nd ed. London: Printed for James Hutton, Bookseller in Fetter Lane, 1749.

Kroyer, Peter. The Story of Lindsey House, Chelsea. London: Country Life, 1956.

“Lebenslauf des Bruders Abraham Louis Brandt, heimgegangen den 23. Juli 1797 in Sarepta.” Nachrichten aus der Brüdergemeine (1857): 49-56.

Lowery, Margaret. Windows of the Morning: A Critical Study of William Blake’s Poetical Sketches, 1783. New Haven: Yale UP, 1940.

Meyer, Henry. Child Nature and Nurture according to Nicolaus Ludwig von Zinzendorf. New York: Abingdon, 1928.

Montgomery, James. Memoirs of the Life and Writings of James Montgomery. Ed. John Holland and James Everett. 7 vols. London: Longmans, 1854-56.

—. The Wanderer of Switzerland, and Other Poems. London: Verner and Hood, 1806.

Nelson, Vernon. Johann Valentin Haidt. Williamsburg: Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Collection, 1966.

—. “John Valentine Haidt’s Theory of Painting.” Transactions of the Moravian Historical Society 23 (1984): 71-78.

Nelson, Vernon, Otto Dreydoppel, Jr., and Doris Rohland Yob, eds. The Bethlehem Diary, Vol. II, January 1, 1744-May 31, 1745. Trans. Kenneth Hamilton and Lothar Madeheim. Bethlehem: Archives of the Moravian Church, 2001.

Peucker, Paul. “‘Blut auf unsre grüne Bändchen’: Die Sichtungszeit in der Herrnhuter Brüdergemeine.” Unitas Fratrum 49/50 (2002): 41-94.

—. “Kreuzbilder und Wundenmalerei: Form und Funktion der Malkunst in der Herrnhuter Brüdergemeine um 1750.” Unitas Fratrum 55/56 (2005): 125-74.

—. “A Painter of Christ’s Wounds: Johann Langguth’s Birthday Poem for Johann Jakob Müller.” Atwood and Vogt 19-33.

Phipps, William E. The Sexuality of Jesus. Cleveland: Pilgrim P, 1996.

Podmore, Colin. The Moravian Church in England, 1728-1760. Oxford: Clarendon P, 1998.

Praz, Mario. Studies in Seventeenth-Century Imagery. 2 vols. London: Warburg Institute, 1939.

Rimius, Henry. A Candid Narrative of the Rise and Progress of the Herrnhuters. London: A. Linde, 1753.

—. A Supplement to the Candid Narrative of the Rise and Progress of the Herrnhuters. London: A. Linde, 1755.

begin page 100 | ↑ back to topSachse, Julius. The German Sectarians of Pennsylvania, 1742-1800. 2 vols. 1899-1900. New York: AMS, 1971.

Sadler, John. J. A. Comenius and the Concept of Universal Education. London: Allen and Unwin, 1966.

Schuchard, Marsha Keith. “Why Mrs. Blake Cried: Swedenborg, Blake, and the Sexual Basis of Spiritual Vision.” Esoterica: The Journal of Esoteric Studies 2 (2000): 45-93. <http://www.esoteric.msu.edu>.

—. Why Mrs. Blake Cried: William Blake and the Sexual Basis of Spiritual Vision. London: Century-Random House, 2006.

Sessler, Jacob John. Communal Pietism among Early American Moravians. New York: Henry Holt, 1933.

Stead, Geoffrey and Margaret. The Exotic Plant: A History of the Moravian Church in Britain, 1742-2000. Peterborough: Epworth, 2003.

Steinberg, Leo. The Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance Art and In Modern Oblivion. 2nd ed. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1996.

Stoudt, John Joseph. Pennsylvania Folk-Art. Allentown: Schlechter’s, 1948.

Swedenborg, Emanuel. The Spiritual Diary. Trans. Alfred Acton. 1962. London: Swedenborg Society, 1977.

—. Swedenborg’s Dream Diary. Ed. Lars Bergquist, trans. Anders Hallengren. West Chester: Swedenborg Foundation, 2001.

Van Kleeck, Justin. “Blake’s Four . . . ‘Zoa’s’?” Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly 39.1 (summer 2005): 38-43.

Wright, Thomas. The Life of William Blake. 2 vols. 1929. New York: Burt Franklin, 1969.

Young, Ruth. Father and Daughter: Jonathan and Maria Spilsbury, 1737-1812: 1777-1820. London: Epworth, 1952.

Zinzendorf, Nikolaus Ludwig von. Nine Public Lectures on Important Subjects in Religion Preached in Fetter Lane Chapel in London in the Year 1746. Trans. and ed. George Forell. Iowa City: U of Iowa P, 1973.

![Dies ist mein lieber

Sohn, an dem ich

wohlgefallen habe

WER DA GLAUBET U[ND] GETAUFFT WIRD DER WIRD SELIG WERDEN X

WER ABER NICHT GLAUBET DER WIRD VERDAMMT WERDEN

Folget mir nach, ich bin das A, u[nd] das O, der

Anfang u[nd] das Ende, der Erste u[nd] der Letzte.](img/illustrations/ChristenABC.frontispiece.40.3.bqscan.png)