note

Two Blake Prints and Two Fuseli Drawings with some possibly pertinent speculations

Toward the end of 1970, during my last visit to London, I went to call on my old friend Ernest Seligmann, the bookseller in Cecil Court, off the Charing Cross Road. Such a visit today, although a luxurious experience, is little more than a courtesy call, for I can seldom afford to buy the treasures which Ernest produces for my delectation and temptation. I think that by now he has almost ceased to look upon me as a genuine customer, but we remain friends in memory of the days before and during World War II when books were still within my means because I had a taste for the off-beat which I then shared with a mere handful of friends, most notably including Geoffrey Grigson. Our caviar was cheap then as there were few competitors who had developed a palate for it, but now the hordes who used to snack on loaves and fishes have become intrigued and so our one-time reasonable delicacies have become as outré as Périgord truffles stuffed with Beluga. Ernest, knowing as well as I did myself that I was not able to buy anything costing more than a pound or two, nonetheless led me into his back room.

He peered at an enormous old cabinet of print-drawers, upon which stacks of books were piled precariously, and then, pausing on occasion to consult his memory as a guide through the maze of magic within the cabinet, dug through drawer after drawer before producing a large manilla envelope. He smiled at me wickedly as he slipped out two old and fragile sheets of paper.

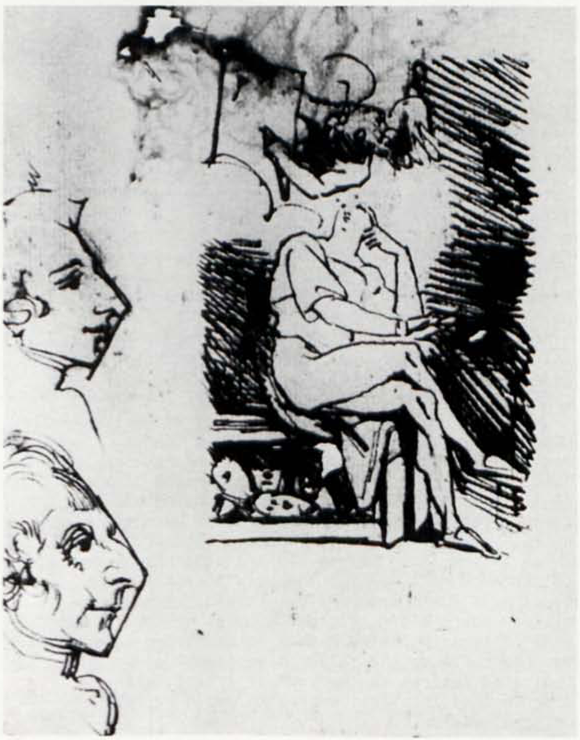

These were passed to me with the right surfaces facing up. I had no difficulty in identifying the unique strangers which I was now handling. They were Henry Fuseli’s original drawings for the plates engraved by Blake as the frontispiece for the Rev. John Caspar Lavater’s Aphorisms on Man, 1788, and for the last page of Fuseli’s own Lectures on Painting, 1801. Clearly such items were not for me to possess and after a long time I laid them aside with a regretful sigh.

Ernest, however, is generous in a stealthy way (he once, knowing I needed copies of the Everyman Gilchrist, had his assistant send me one as a gift with a note saying that Mr. Seligmann had asked him to send it off, just before he himself went into hospital). I dropped by his shop a couple of weeks later as I wanted to take another look at the Fuseli drawings, to pin them like butterflies to cork on my memory, before they

So I want to celebrate and thank Ernest Seligmann, one of the great art-booksellers I have known in any country, for the thoughtful generosity which has inspired and made possible this venture.

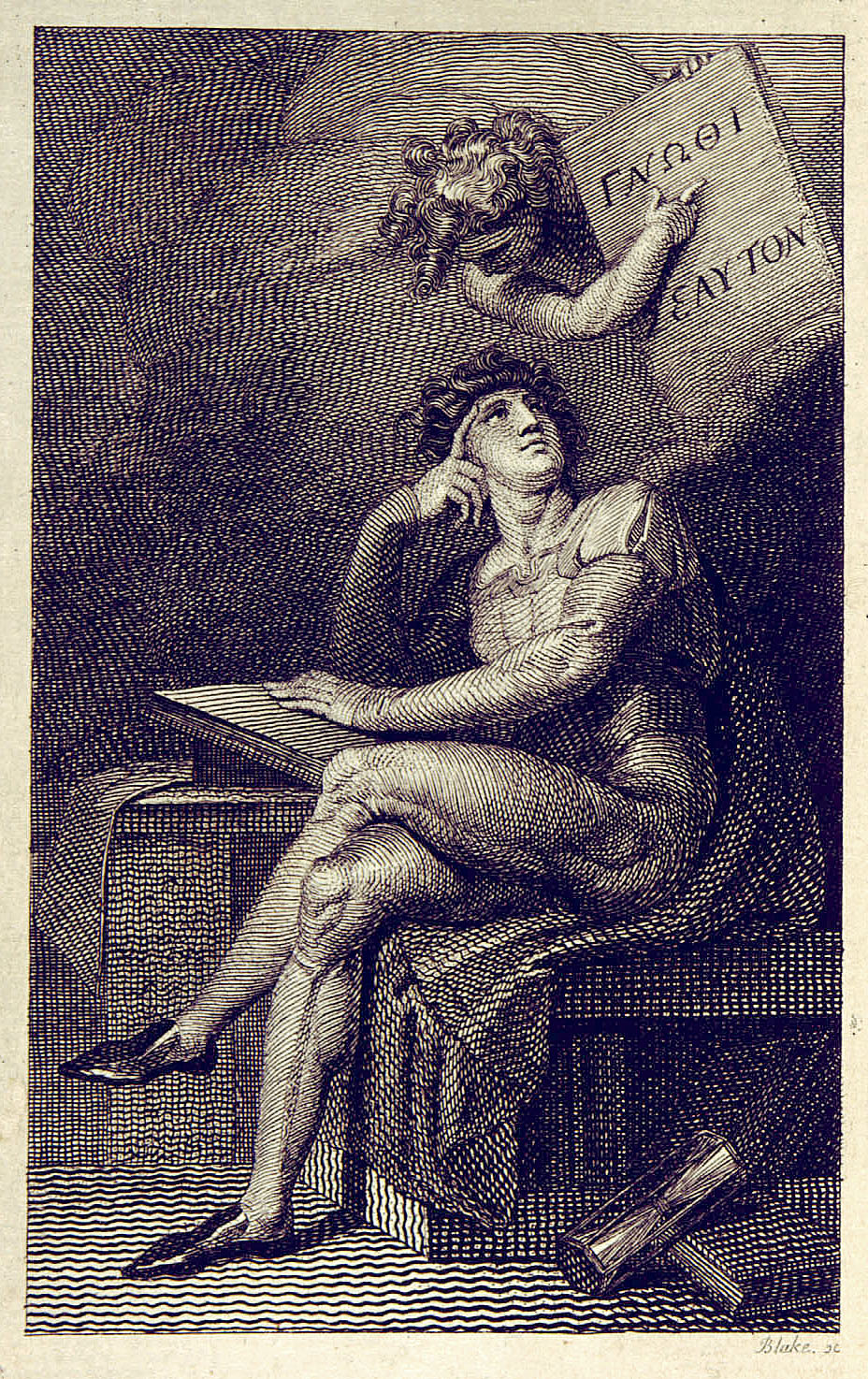

Apparently afraid to go out on a limb, G. E. Bentley, Jr., and Martin K. Nurmi, in their A Blake Bibliography, 1964, in describing the Aphorisms on Man go no further than to suggest that “the frontispiece, representing a seated man, looking up, is signed ‘Blake sc,’ and was probably [my italics] designed by Fuseli.” The engraving, 120 × 75 mm., is known in three states, all to be seen in the Rosenwald Collection of the Library of Congress. The third is reproduced here [fig. 1] as it, presumably, shows the final intentions of both artist and engraver.

As his plentiful annotations on his own copy (now in the Huntington Library) show, the book was of immediate importance to Blake, but it was also highly significant for Henry Fuseli who had not only translated it from the German manuscript with considerable freedom but had also supplied the introduction.

It was issued as the first of a proposed pair of volumes, of which the second was intended to be Fuseli’s own Aphorisms on Art. According to his official biographer, John Knowles, The Life and Writings of Henry Fuseli, 1831, vol. I, p. 160: “In conformity with this intention, one sheet was worked off and corrected by him; but an accidental fire having taken place in the premises of the printer, the whole impression was destroyed, and Fuseli could never bring himself to undergo the task of another revision.” However, as Eudo C. Mason, The Mind of Henry Fuseli, 1951, p. 33, points out, “he was engaged intermittently from 1788 till 1818” in writing his Aphorisms chiefly relative to The Fine Arts which were eventually printed by Knowles, vol. III, pp. 63-150.

Looking at the pen drawing [fig. 2], approximately 105 × 70 mm., on a sheet 205 × 165 mm., one is immediately surprised by the almost perfunctory character of the sketch, leaving so much to the imagination of the engraver, being offered as the frontispiece to a book written by the artist’s earliest friend. A book, moreover, into which in the liberties of his translation, he had put so much of himself. The only possible conclusion is that, around 1788, Fuseli, although sixteen years older than Blake, must have felt the bond of sympathy between them to be strong enough for him to leave the fuller development of his indicated desires to the younger artist, with confidence that the final engraving would express his original vision.

The engraving is the reverse-image of the sketch, which means that Blake did not make a special drawing or otherwise transfer it in reverse to the surface of the copper plate, as was common engraver’s practice. The additions and alterations which occur between the drawing and the engraving are astonishing. The rather smudgy cherub of the drawing seems to be carrying an opened folio sheet of paper which, in the engraving, has become a tablet of stone bearing an inscription in Greek. This, quoted in Greek from Socrates, in the line from Juvenal’s Ninth Satire, on the title-page, merely means “Know thyself.” Fuseli must have written out the two words as, at that time, Blake had probably not yet attempted to learn Greek. Th This, as well as the existence of three states, suggests that there must have been consultations between the two during the course of the engraving. There are, too, lines suggestive of wings curving from both shoulders of the cherub, which Blake has ignored. These remind one of Allan Cunningham’s story (Lives of the Most Eminent British Painters . . . , 1830, vol. II, p. 286) about Fuseli looking at the first sketch of some angels which he had made for a painting in his Milton Gallery and exclaiming “—for he generally thought aloud—‘They shall rise without wings.’” Blake’s wingless cherub, despite the apparent weight of the tablet, hovers without effort.

Although the posture of Blake’s lower figure is approximately the same as Fuseli’s, a low table has been added in the background. From this a cloth or limp sheet of paper droops from beneath a stand upon which a book rests, which, in turn, supports the left hand of the figure. Both the cloak, apparently flowing from the right shoulder, and details of the clothing have been changed and clarified. The hollow bench upon which the pensive begin page 175 | ↑ back to top man sits in Fuseli’s drawing is filled with unidentifiable objects, some resembling caricatures of babies’ skulls. Blake has transformed the bench into a bookshelf, before which a volume lies upon its side with an hour-glass tilted against it. It is impossible, though I would not suggest it as fact, that the upper face in the left margin of Fuseli’s drawing may have suggested to Blake the face, seen from the front and slanted upward, in the engraving. Both share the “Grecian” line running in a straight diagonal from the tip of the nose to the top of the forehead.

On the verso of Fuseli’s drawing [fig. 3], to the left and below the seated female figure with a child sprawled against her right foot, there is an extremely faint pencil note in what looks like John Linnell’s hand: “Given by W. Blake to J. Linnell / by Fuseli.”

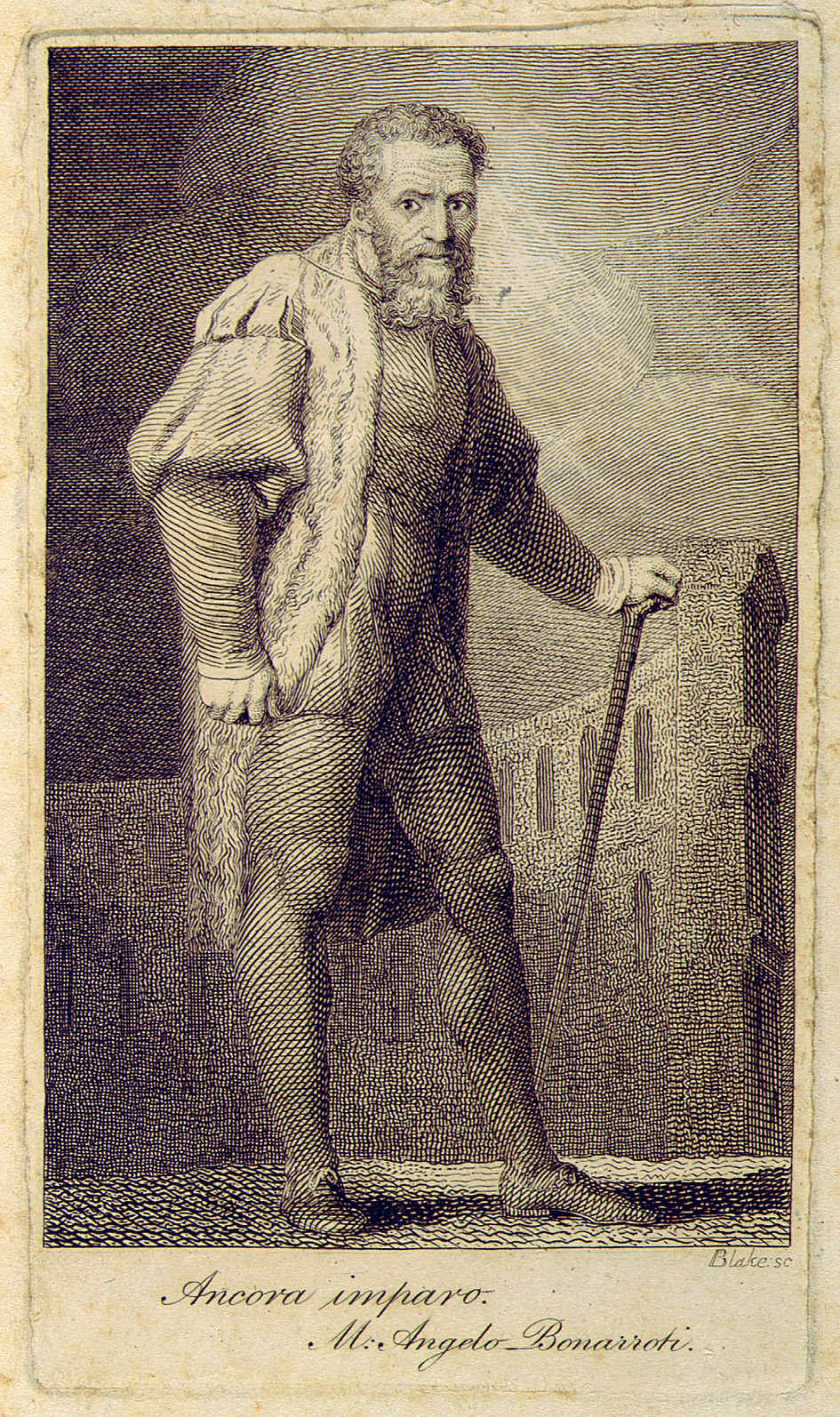

Fuseli, who had become Professor of Painting at the Royal Academy in 1799 (he was to be elected Keeper in 1804 and, in 1810, by special dispensation, was re-elected to the Professorship and allowed to draw the salary from both posts), delivered three lectures on painting on March 16, 23 and 30, 1801. These were published as a handsome quarto in the same year. On the last page, below the final four lines of the Third Lecture, there is an engraving of Michelangelo, 133 × 79 mm., signed “Blake sc” in the lower right [fig. 4]. A proof of this, bearing Fuseli’s name as well as Blake’s, is in the British Museum Print Room.

The pen drawing [fig. 5], about 185 × 135 mm., on a sheet 200 × 168 mm., is rather more explicit than the sketch for the Aphorisms on Man, but it still seems to display Fuseli’s implicit trust in Blake’s ability to produce a fully finished engraving from a rather tentative suggestion. It is likely, from the style of the drawing, that it was done at least ten years earlier, and was not drawn especially for the Lectures on Painting in 1801; this is a matter to which I will return later. (Sir Geoffrey Keynes, A Bibliography of William Blake, 1921, p. 248, states that “Blake’s engraving is reduced and considerably altered from Fuseli’s

The drawing in pen extends only as far as the crotch of the figure of Michelangelo. However, in the upper right corner, there is a light pencil sketch, about 83 × 56 mm., of legs against an abbreviated cloak, very much as these details appear in the engraving. David Bindman and Martin Butlin think it probable that this pencil work is by Blake and not by Fuseli, and I agree with them. The line is more like that of Blake’s pencil drawings than of Fuseli’s in this period.

The difference between the Michelangelo sketched by Fuseli and the final engraving by Blake is extremely striking. Fuseli’s Michelangelo is shown with rather sparse yet unkempt hair on his head; his beard is brief and straggly and the expression on his face is disgruntled if not actually embittered.

In the engraving, where Michelangelo has been immeasurably ennobled, both the hair and the beard have become more abundant and well-trimmed, in masses of rather tight curls. The expression on his face is, perhaps, one of expectancy or at least of an acute awareness of the world at which he is gazing, a world behind the spectator of the print. The cloak, which in the pen drawing trails off toward the bottom of the page, has become close to that in the pencil sketch, finishing about a hand’s breadth below the knees.

As a background, some distance behind Michelangelo, Blake has added a stylized curving Roman building, and he has also defined the clouds in the sky.

In the lower left corner, the drawing bears the pencil inscription, in the hand of William Linnell [?]: “Mich! Angelo / by Fuseli / original Drawing had from WT Blake.”

Although I do not know the history of the two drawings between their leaving the possession of the Linnell family and their present resting place in the good safe hands of my old friend Ernest Seligmann, the inscriptions upon them, undoubtedly made by members of the Linnell family, with the suggestion of the first having been a gift, do not tally with the only mention of Fuseli drawings made in G. E. Bentley, Jr.’s listing of the Linnell accounts in Blake Records, 1969, p. 596: “[Jan. 26 (1820)] to Mrs. Blake on acct. for a Drawing of Heads by Mr. Blake & two by Fuseli [£] l — —.”

Having ventured so far, on the basis of the two Fuseli drawings which I have been able to reproduce here (along with the versos since they may contain material for someone with a different visual memory from my own; figure 6 showing the verso of the Michelangelo drawing), and Blake’s engravings which derive from them, I find myself unable to bring the matter to an abrupt and completely factual close.

At present I am engaged in writing a 25,000 word introduction to a picture-book on Fuseli and, as is inevitable with me, I have been doing more research than is needed for such a lightweight undertaking. One result of this is that I feel I should not only record my findings but also indulge in some speculation which I have, perhaps perversely, persuaded myself to be pertinent.

Blake did engravings after Fuseli for nine volumes, fifteen plates in all. In addition three separate plates are known and have been described, as well as two others which, although destined for his burin, it is probable that he did not start. I will attempt to deal with these items before proceeding with my speculations and my reasons for presenting them.

Since starting work upon this study, I have received two most interesting letters, dated 28 July and 18 September 1971, from Gert Schiff and I have taken the liberty of quoting from them in the appropriate places. Gert Schiff has, after many years of work, completed his Catalogue Raisonné of the work of Fuseli, the two volumes of which, text and illustrations, are due to appear in Switzerland early in 1972. My gratitude to him for his comments upon my queries is immeasurable.

The books are, in chronological order:

-

John Caspar Lavater, Aphorisms on Man, J. Johnson, 1788. The half-title reads “Aphorisms. Vol. I.” Apart from comparisons of the three states, the frontispiece has been dealt with above.

Erasmus Darwin, The Botanic Garden, J. Johnson, 1791. This contains the plate “Fertilization of Egypt.” In the British Museum Print Room are both Fuseli’s pencil drawing of the central figure, representing the Nile, inscribed by Frederick Tatham [?] “Sketched by Fuseli for Blake

begin page 177 | ↑ back to top to engrave from,” and Blake’s more complete realization of the whole subject. Here it strikes me as odd that a man who once wrote in a friend’s album (Knowles, vol. I, p. 396), “I do not wish to build a cottage, but to erect a pyramid,” should have left it to his engraver to supply him with pyramids.Both drawings are reproduced in Sir Anthony Blunt’s The Art of William Blake, 1959, pls. 21a and 21b, with 21c showing a drawing by George Romney which closely resembles the hovering figure to be seen between the legs in Blake’s drawing. The actual engraving can be seen in Kathleen Raine’s William Blake, 1970, p. 33, pl. 18.

-

Erasmus Darwin, The Botanic Garden, The Third Edition, J. Johnson, 1795, has the extra plate “Tornado” (reproduced in my own “Pictureback,” William Blake The Artist, 1971, p. 42). There is an early proof of the engraving in the British Museum Print Room. Although the published print bears the date “Augt. 1st. 1795,” it was probably executed about the same time as the “Fertilization of Egypt.” Gert Schiff knows of no drawing for this.

“Tornado” did not appear in the first two editions, and was not re-engraved for the Fourth (see item 6). It is possible that, although for some reason it did not appeal to Erasmus Darwin, Joseph Johnson, having paid for the engraving of the plate, insisted upon trying it out in at least one edition.

-

Charles Allen, A New and Improved History of England, J. Johnson, 1798.

-

Charles Allen, A New and Improved Roman History, J. Johnson, 1798.

Since the plates in both books are dated “Decr. 1, 1797,” it is simpler to deal with them together. Archibald G. B. Russell, The Engravings of William Blake, 1912, states of the second book that the plates were engraved “after designs in the manner of Fuseli,” but Sir Geoffrey Keynes, in his Bibliography, shows no hesitation in attributing the four plates in each volume to Fuseli and now I can see no reason for disagreement.

Frederick Antal, Fuseli Studies, 1956, pl. 33a, reproduced “King John absolved by Cardinal Pandulph” from the first book. This shows much the same triviality of draftsmanship as, say, that in the emblematic frontispiece to Fuseli’s own Remarks on the Writings and Conduct of John James Rousseau, 1767, reproduced by Eudo C. Mason, facing p. 305 in my copy although given as p. 136 in the list of illustrations, and described, for some unknown reason, as a “woodcut” by Grignion.

The History of England contains “Alfred and the Neat-herd’s Wife,” “King John absolved by Cardinal Pandulph,” “Wat Tyler and the Tax-Gatherer” and “Queen Elizabeth and Essex,” while the Roman History has “Mars and Rhea Silvia,” “The Death of Lucretia,” “C. Marius at Minturnum” and “The Death of Cleopatra.”

Gert Schiff has traced no drawings for these; “only a rather weak and badly overpainted painting of Wat Tyler killing the Tax-Gatherer is known (Zürich, coll. Dr. Conrad Ulrich).”

My major concern here is the date, 1797, engraved on the plates. I would suggest that they were executed, even if not quite finished, considerably earlier. In 1797 Blake was engaged with his work on Edward Young’s Night Thoughts and was full of optimism about his future. Among other things he had been commissioned by John Flaxman to prepare a specially illustrated copy of Thomas Gray’s Poems, eventually given to the sculptor’s wife, Nancy, sometime before September 1805. He would hardly, in such rosy circumstances, have stooped to undertake such menial and trivial work unless fulfilling a promise made long before. In that year, too, Fuseli was ebullient for, having been in doubt about his plans for his Milton Gallery (see Knowles, vol. I, p. 190), he had received a guarantee from six patrons to provide him with fifty pounds from each “until the task was completed.”

-

Erasmus Darwin, The Botanic Garden, The Fourth Edition, J. Johnson, 1799. This edition, reduced from quarto to octavo, contains “Fertilization of Egypt,” rather coarsely re-engraved by Blake from the larger version, but, like the other plates engraved by Blake in the book, it is dated “Decr. 1st. 1791.” It seems highly improbable that Johnson, in 1791, should have considered issuing an inferior octavo edition at the same time as his rather elegant quarto. A more likely suggestion is that Blake did do the re-engraving in 1799 when he was suffering from the general slump in the employment of commercial engravers, and depressed by the failure of his Night Thoughts. The dating may be due to some personal quirk on the part of Darwin or Johnson, indicating that the book had not been revised, and the poor quality of the engraving in all Blake’s plates in the volume suggests that it was probably a cut-price job, done in a hurry. Gert Schiff thanks me for a “most convincing hypothesis as to the dating of these plates!”

-

Henry Fuseli, Lectures on Painting, J. Johnson, 1801. In the absence of the “wash drawing” mentioned by Sir Geoffrey Keynes, I can only go on the drawing which I know personally. As I have stated, I think that the original drawing of Michelangelo by Fuseli dates from about the same time as the frontispiece for the Aphorisms on Man. It is admittedly difficult to pin down the date of any one of Fuseli’s drawings on purely stylistic grounds, but I would suggest that this drawing was almost certainly made sometime earlier than 1792. Possible extra evidence is also given by Paul Ganz, The Drawings of Henry Fuseli, 1949, p. 23, where he remarks: “After 1800, he seems to have finally given up drawing with the pen.” The style of the engraving, too, has much in common with other work which is definitely known to have been done by Blake around 1790.

With no more evidence than this, and perhaps the knowledge that the last lecture, delivered on March 30, appeared in an elegant book published in begin page 178 | ↑ back to top May, I would venture to suggest that the plate was actually engraved about the same time as the frontispiece for Lavater’s book. Although it is somewhat larger and certainly a much more important engraving than that plate—as is vouchsafed by Blake’s going to the trouble of reversing it on the copper so that the print would appear the same way round as the drawing—the Michelangelo would just have fitted into the format of the earlier volume.

My speculation, for it can claim to be no more unless further information turns up, is that it was intended to be the frontispiece for “Aphorisms. Vol. II,” Fuseli’s projected but destroyed Aphorisms on Art. There can be no doubt that he wrote the “Advertisement” declaring that “It is the intention of the editor to add another volume of APHORISMS ON ART, WITH CHARACTERS AND EXAMPLES, not indeed by the same author, which the reader may expect in the course of the year.”

Fuseli’s discouragement in 1788 at the destruction of his carefully corrected proof-sheet (and he was a slow and careful corrector of his own written work) should be seen in the more glaring light of the earlier fire at Joseph Johnson’s, on 8 January 1770, in which he lost almost all he possessed, including his manuscripts and the majority of the drawings which led Sir Joshua Reynolds to advise him to become a painter.

Anyone who has read Eudo C. Mason’s The Mind of Henry Fuseli is bound to recognize that it was quite in keeping with Fuseli’s character to aggrandize himself even at the expense of his oldest friend and, furthermore, although he was to fluctuate in his opinions of Michelangelo later, in the years around 1790 the Italian was his god.

If my suggestion is accepted as valid—and Gert Schiff finds it interesting, although he lacks the time to follow it up—it is more than likely that Joseph Johnson, who published all the books upon which Blake worked in collaboration with Fuseli, had also presumably paid Blake for the engraving of Michelangelo meant for the aborted second volume and when he came to publish the Lectures in considerable haste some dozen years later decided to make use of the plate.

“Silence,” engraved by F. Legat after Fuseli, which appears on the title-page, may also have been a plate Johnson had in reserve. Certainly the subject has little to do with the sound of lecturing.

Finally, so far as the books are concerned, there are two volumes of Alexander Chalmers’s The Plays of William Shakespeare . . . , J. Johnson [with many others], 1805.

-

Vol. VII, p. 235. “Queen Katherine’s Dream.” “Act IV. King Henry VIII. Sc. II.”

-

Vol. X, p. 107. “Romeo and the Apothecary.” “Act I [sic for V]. Romeo and Juliet. Sc, I.”

These two plates seem to be connected with a revival of an old friendship between the two men. Fuseli, with the support of his rich patrons was suffering from no financial hardship but was probably still depressed by the final failure of his Milton Gallery, and this may have drawn him back to his old friend when Blake returned to London from Felpham in September 1803.

Gert Schiff knows of no drawings for either plate, but there are proofs of them in the Rosenwald Collection of the Library of Congress and in the collection of Dr. Charles Ryskamp of the Morgan Library. In addition, a footnote by Sir Geoffrey Keynes, in his edition of Mona Wilson, The Life of William Blake, 1971, p. 214, notes of “Queen Katherine’s Dream” that “The pencil drawing made by Blake for this engraving is now in the Rosenwald Collection, National Gallery, Washington, D.C.”

The three individual prints are listed by Sir Geoffrey Keynes, The Separate Plates, 1956, quoting Russell, The Engravings, 1912, for descriptions of the first and third. I use Sir Geoffrey’s numbers here, and also his recording of the number of impressions known to him at the date of publication of his book.

No. XXXIII, “Timon and Alcibiades” was acquired by the British Museum Print Room in 1863. Although apparently a unique copy, this is the only one of these three prints to carry any inscription which indicates an intention of publishing it: “Published by W. Blake, Poland St. July 28: 1790.” Gert Schiff tells me that there are two drawings for this, one reproduced by Nicholas Powell, The Drawings of Henry Fuseli, 1950, and the other in the Art Gallery, Aukland, New Zealand, and reproduced in the catalogue of the Fuseli drawings there.

No. XXXIV, c. 1790?, “Satan,” also known as the “Head of a Man Tormented in Fire,” has a listing of no less than six copies, to which I can add a seventh at the University of Glasgow. This rather repulsive and intimidating head, 350 × 263 mm. on the plate, derives from or is connected with, according to Gert Schiff, a head in Lavater’s Essays on Physiognomy, 1792, vol. II, p. 290. It became no less terrifying but certainly more acceptable when it was adopted and reduced by Blake in plate 16 of Illustrations of the Book of Job, “Satan cast forth.”

In London, early in 1971, I was shown a drawing which might either have been a copy of Fuseli’s original or of Blake’s engraving. David Bindman, to whom it belongs, suggested that it might possibly be the work of the octogenarian Fuseli’s prodigy protégé, Theodore Matthias von Holst. Gert Schiff, however, writes, “I know of an oil on paper copy of this head which was once with a young London dealer . . . , but this certainly had nothing to do with Von Holst.”

No. XXXV, c. 1790?, “FALSA AD COELUM MITTUNT INSOMNIA MANES,” is described, by Russell, from the copy which the British Museum Print Room obtained in 1882. Sir Geoffrey mentions having heard of another about which, however, he seems to have been unable to obtain any details. Despite his wide begin page 179 | ↑ back to top knowledge of Swiss collections, Gert Schiff has failed to trace other impressions of this or the “Timon.” He writes, however, “Falsa ad coelum: in my opinion not etched by Blake but by Fuseli himself (lefthandedness!) Iconographically one of the most involved, and charming, allegories Fuseli ever invented.” As the plate is a line-engraving, it is possible that Fuseli may have etched the outlines and some sections of the plate before Blake’s burin took over. The use of etching for laying-out a plate before it was engraved was common usage. I wrote to Gert Schiff suggesting this, and in his later letter he says, “Your proposal of a collaboration of Fuseli and Blake in the plate seems fascinating, however, I have no reproduction at hand and thus cannot really form an opinion. What induced me to give the whole of its execution to Fuseli is the clear lefthandedness.”

I know too little about Fuseli’s accomplishment as an etcher or engraver to be dogmatic, but judging from the impatience of his temperament alone, I have never been convinced by the plate, in what seems to be a mixture of mezzotint and engraving, credited to Fuseli himself by Antal, pl. 33b, “Religious Fanaticism attended by Folly trampling upon Truth.”

The two phantasmagoric plates can be dealt with briefly. Eudo C. Mason reproduces (facing p. 208 of my copy although listed as facing p. 304) a “finished sketch” which he credits to Fuseli. This he considers may be “Satan taking his flight from Chaos,” intended as an illustration for Cowper’s proposed edition of Milton’s poems, which had to be abandoned when the editor became insane. Knowles, vol. I, p. 172, declares this to have been “ready for the graver of Blake” before August 1790, but no proof of any print has been traced, nor has any copy emerged of the other proposed engraving mentioned by Knowles in the same sentence in connection with Blake, “Adam and Eve observed by Satan.”

In connection with these two works Gert Schiff comments: “Satan taking his flight, as published by Mason, or The Night Hag, as published by Ganz: definitely not by Fuseli, but possibly by Prince Hoare, and perhaps related to the lost painting no. VIII of Fuseli’s Milton Gallery, The Night Hag and the Lapland Witches. Adam and Eve first observed by Satan; a fragment of the painting, the figures of Adam and Eve, half-length, embracing, is with Kurt Meissner, Zürich, an unfinished sketch by Fuseli is in the Kunsthaus [Zürich].”

My point in listing and commenting, however incompletely, upon all Blake’s known engravings after Fuseli, as well as a couple which he may not have started, has been to suggest that, despite the conflicting given dates of publication, for a short period, roughly from late 1787 to early 1792, the two men were in closer contact and enjoyed more absolute sympathy with each other than at any other time during their friendship. While this continued (allowing my surmises about the Michelangelo plate to be correct) Fuseli had an overwhelming confidence in Blake’s ability to realize his wishes in a finished engraving.

That Fuseli developed a mistrust of Blake’s ever-widening expanse of vision (although Joseph Farington reports a conversation of 12 January 1797 in which Thomas Stothard claimed that Blake “had been misled to extravagance in his art” by Fuseli himself), while his own ambitions developed in other directions, particularly erotically, is clear to anyone who has studied the lives and works of both.

Still, although they saw less and less of each other as the years went by and the intense intimacy of these five years was gradually smoothed away, the friendship never perished completely. I have suggested a slight rebirth of intimacy in the early 1800’s, and further evidence of this is shown by Fuseli’s advertisement for Blake’s illustrations to Robert Blair’s The Grave, written in 1805, and in Blake’s letter of June 1806 published in the Monthly Magazine, defending Fuseli’s “Ugolino,” shown in the Royal Academy of that year, against a particularly spiteful attack in Bell’s Weekly Messenger. It seems likely that Blake’s quatrain

The only Man that eer I knewbelongs to the years between 1803 and 1806.

Who did not make me almost spew

Was Fuseli he was both Turk & Jew

And so dear Christian Friends how do you do

I have recently been investigating the matter of the Truchsessian Gallery which, as his letter of 23 October 1804 to William Hayley shows, had an overwhelming effect upon Blake. A discussion of the Gallery does not belong here, but there are points which can be raised in support of my belief in a renewal of friendship during these years. Owing to the differences in sizes and typography of the printed documents relating to the collection, I decided to make a typescript of all I could obtain as they came to hand.

Typing out what seems to have been the second of Count Joseph Truchsess’s Proposals for the Establishment of a Public Gallery of Pictures in London . . . . [31 July 1802], from a Xerox copy generously given me by Paul Grinke (another copy being in the Bodleian Library, Oxford), I was struck by something which had made little impact during my earlier reading. The Count’s chief bankers were Thomas Coutts and Co. Fuseli became intimate with Thomas Coutts on his first visit to England in 1763 and the banker was to remain his friend and steadfast patron until his death in 1822, when his place was taken by his daughter, the Countess of Guildford, in whose house at Putney Fuseli was to die in 1825.

Proceeding to the Plan of Subscription . . . for the Purchase of the Truchsessian Picture-Gallery . . . [15 January 1804], known to me only from the Xerox most kindly given me by Paul Grinke, I found more which seemed pertinent. Among other information I gathered that admittance to the Gallery cost half-a-crown, a large sum of money in those days, when entry to Fuseli’s Milton Gallery had been one shilling, with sixpence for the catalogue. Most of the pamphlet is concerned with a begin page 180 | ↑ back to top have given Blake the full use of the Gallery.

Having also acquired Xerox copies of the Catalogue of the Truchsessian Picture Gallery, now exhibiting in the New Road, opposite Portland Place . . . [1803], and the Sale Catalogue of March, April, May, 1806 (both from the Bodleian Library), I have become more aware of the problems which can be aroused by the contents of the collection. But this, as I have remarked, is not the place for me to approach these.

In the Catalogue of the Exhibition, I found even stronger indications of a connection between Count Truchsess and Fuseli. The entry reads: “BRUN. (Bartholomaeus). There are several german engravers of this name, who lived at the beginning of the sixteenth century. But the name of this master, written upon the picture, with the year 1532, has escaped the researches of the grand dictionary, published by Füseli.” As Fuseli’s first revision of Matthew Pilkington’s Dictionary of Painters was not published until 1805, this is evidence that the Count, in 1803, must have had access to the corrected sheets as they came from number of “rules” under the heading “Terms of Subscription.”

The first rule reads: “Every person who shall subscribe [‘Five pounds’ inserted in ink above line] previous to the first of May, 1804, on the payment of this subscription, shall receive a printed ticket, acknowledging the sum paid; and this ticket will give that person, for the term of ten years, the right of free admission to the Truchsessian Gallery, at whatever state of augmentation and improvement it may arrive, after having become a national property.”

After the rules applying to the subscribers of larger sums and other matters, I arrived at rule seven. “Institution of a Gallery of painting being particularly intended for the use of the artists, every member of the Royal Academy, and also every Painter, Sculptor, or Engraver properly introduced, shall acquire the right of a Subscriber in either of the aforesaid classes, by paying half the subscription-money attached to them; and all such artists, as well as any amateur known to exercise any one of the fine arts, being subscribers, will be admitted to the Gallery during the summer half-year an hour before the ordinary time of opening, and have, all the time it stands open, the right to make studies and drawings in their portfolios from whatever subject they please; but no picture can be removed from it’s [sic] place, nor can tables and easels be granted, until a larger building afford sufficient room. It is likewise understood that no formal copy or engraving after any picture is to be made, without the assent of the Trustees and Directors of the Gallery being first obtained.”

It seems more than possible that the Count’s banker, Thomas Coutts, might well have supplied his old intimate (I believe that Fuseli’s erotic drawings are closely connected with this friendship) with at least the minimum “Subscription.” Fuseli in turn may have performed the “proper introduction” and paid the two pounds ten shillings which would the printer. It is also worth noting that artists whose names appear early in the alphabet receive fuller treatment than those mentioned later.

All this is a weak thread of evidence rather than a chain, but it is unlikely that Blake, in 1804, was in a position to pay two shillings and sixpence in visiting a picture-gallery and his enthusiasm suggests that he had seen the pictures more than once.

It was possibly in reaction against the cost of admission to the Truchsessian Gallery that when Blake held his own Exhibition in 1809 the cost of A Descriptive Catalogue, certainly an awe-inspiring amount of reading material, was two shillings and sixpence which included admission to the Exhibition. Further, in the unique page of advertisement I found in 1942 in the Stirling Maxwell collection (now at the University of Glasgow), Blake is clearly tempering the wind when he states “Admittance to the Exhibition 1 Shilling; and Index to the Catalogue gratis.” (No copy of this separate Index seems to have survived or been traced.)

An added hint about this temporary revival of a former friendship is shown in Fuseli’s having become choosy about the quality of craftsmanship and interpretation of his works by engravers about the year 1803. In that year, having taken “the lease of a commodious house, No. 13, Berner’s Street,” he offered rooms in this to Moses Haughton and the following year he took Haughton with him when he moved into “the commodious apartments allotted” to him in Somerset House as Keeper of the Royal Academy (Knowles, vol. I, p. 284). Haughton, an accurate if somewhat pedestrian engraver, remained there until 1818 working under the direct supervision of his somewhat cantankerous patron who knew what he wanted and insisted upon getting it.

Seldom indeed does such rapport exist between a designer and his engraver as seems to have existed between Fuseli and Blake during the earlier and brief and undoubtedly exciting stretch of time. Blake’s own recognition of the brevity is expressed in his letter of 12 September 1880 to John Flaxman, where he refers to the departure of the latter for Rome in 1787 and says “Fuseli was given to me for a season.” No such bond ever seems to have developed between Fuseli and his chosen and innocuous interpreter, Moses Haughton.

Certainly Thomas Stothard never permitted Blake such an unbridled freedom of imagination, judging from the careful drawings for engravings to be made by the latter which I have so far seen. It may be that Fuseli, using his own peculiar and profane version of the English language, managed to communicate his intentions and desires to the younger man more completely than, say, George Cumberland, John Flaxman or Stothard were ever able to do, although they were compatriots.

Of course, here I have had to avoid any attempt at an exploration of the visual influence of either artist upon the other. I have been long-winded begin page 181 | ↑ back to top enough in my attempt to suggest that there may indeed have been this brilliant interval, short in the long lives of both artists, when it seems that they may have shared a mutual vision.

Since this has been, of necessity, a speculative argument, I will welcome any expressions of disagreement or fragments of enlightenment which anyone cares to offer, either to me personally or through the pages of Blake Newsletter. I will, naturally, be delighted if anyone can add any information about the short period when I believe that the ideals and imaginations of the two artists actually coalesced.