REVIEWS

On Tame High Finishers of Paltry

Harmonies

A Blake Music Review & Checklist

Every thing which is in harmony with me I call In harmony—But there may be things which are Not in harmony with Me & yet are in a More perfect Harmony. (MS Notebook 1808-11, K 559)

One pairing of Contraries immediately appears germane to any attempt at analysis of “tunings,” settings-to-music of the writings of Blake. These Contraries may best be identified through usage of terms which, philosophically, have become near-clichés. Coincidentally, the terms themselves indicate the antiquity of such dialogue. I speak of “Apollonian” vs. “Dionysian” (or “Orphic”).

Within the mythography of Blake, we may approximately substitute “Urizenic” for the former and “Orcian” or “Rintrahist” for the latter. Or, in other contexts, the pitting of the “Horses of Instruction” against the “Tygers of Wrath” comes to mind.

In musical terms, this may be presented as the ongoing dispute between “classical” musicians of West-European-derived “schools” and the sometimes consciously anti-intellectual proponents of “free” or “folk” music. The approach, however, seems applicable to any discussion of creative means and ends lying within the broad compass of the Arts. Furthermore, the dispute involves the distinction between “structured” and “unstructured” artistic creation, whether one is speaking of the original production of a work or its re-creation via performance or graphic reproduction. Both approaches have had their adherents down through the ages, often to the point of quite ridiculous degrees of cultic ardor and snobbishness.

At first glance it would seem that Blake’s musical preferences lay most strongly with the ecstatics. J. T. Smith attests (“A Book for a Rainy Day,” London, 1845, cited in Blake Records, p. 26) that he heard Blake both read and sing his poems. In “Nollekens and his Times,” 1828, Smith reports that “Blake wrote many other songs, to which he also composed tunes. These he would occasionally sing to his friends; and though, according to his confession, he was entirely unacquainted with the science of music, his ear was so good, that his tunes were sometimes most singularly beautiful, and were noted down by musical professors” (BR 457). Allan Cunningham, in “Lives of the Most Eminent British Painters, Sculptors, and Architects,” 1830, adds that “In sketching designs, engraving plates, writing songs, and composing music, he employed his time, with his wife sitting at his side, encouraging him in all his undertakings. As he drew the figure he meditated the song which was to accompany it, and the music to which the verse was to be sung, was the offspring too of the same moment. Of his music there are no specimens—he wanted the art of noting it down—if it equalled many of his drawings, and some of his songs, we have lost melodies of real value” (BR 482).

Gilchrist, in his 1863 Life, records Mrs. Linnell’s letter of 13 October 1825:

He [Blake] was very fond of hearing Mrs. Linnell sing Scottish songs, and would sit by the pianoforte, tears falling from his eyes, while he listened to the Border Melody, to which the song is set, commencing—

‘O Nancy’s hair is yellow as gowd,

And her een as the lift are blue.’

To simple national melodies Blake was very impressionable, though not so to music of more complicated structure. He himself still sang, in a voice tremulous with age, sometimes old ballads, sometimes his own songs, to melodies of his own. (BR 305)

Finally, Cunningham states that even on his death-bed Blake sang: “The very joyfulness with which this singular man welcomed the coming of begin page 90 | ↑ back to top

begin page 92 | ↑ back to top death, made his dying moments intensely mournful. He lay chaunting songs, and the verses and the music were both the offspring of the moment” (BR 502).What music of his period Blake heard performed is scarcely recorded. Blake Records (pp. 272-73) quotes from Linnell’s daily Journal that in 1821 Linnell and Blake twice attended the Theatre in Drury Lane when “musical pieces” were performed. These were J. H. Payne’s “Therèse, the Orphan of Geneva,” and Mozart’s and Rossini’s music used as settings in a “New Grand Serious Opera” entitled “Dirce, or the Fatal Urn.” It is obvious that Blake was familiar with other, more lasting musical efforts than these. The only reference, however, to a specific musical composition I have found is in An Island in the Moon. Here, immediately following Mr. Scoprell’s marvelous parody of a pompous music master is: “ ‘Hm,’ said the Lawgiver, ‘Funny enough! Let’s have handel’s water piece.’ ” (K 62).

In Blake’s words, “Music as it exists in old tunes or melodies . . . is Inspiration and cannot be surpassed” (Descriptive Catalogue, K 579); “Nature has no Tune, but Imagination has” (Ghost of Abel I:3); “Demonstration, Similitude & Harmony are Objects of Reasoning. Invention, Identity & Melody are Objects of Intuition” (On Reynolds, K 474); “ . . . the tame high finisher of paltry Blots Indefinite, or paltry Rhymes, or paltry Harmonies” (Milton 41:9)); “ . . . how Albion’s Sons, by Harmonies of Concords & Discords Opposed to Melody” (Jerusalem 74:25). If we let it go at these references, so direct and thus typically Blakean, a reviewer of musical settings of Blakean texts might be tempted to throw out 99% of them as inappropriate to Blake’s intent! The question then arises as to whether or not they constitute, in sum, a non sequitur of sorts in the hearing of the multitudinous settings. I think not.

The entire “program” of psychic development as set forth by Blake as “psychic Columbus,” i.e., the progression of the human soul individually or collectively, from Innocence through Experience into Organized Innocence, which seems so closely to parallel the reconciliation of opposites into the Absolute of Oriental thought works against Blake’s seeming condemnation of musical harmonization per se. Indeed, a look at the Blakean vision of the Last Days, as drawn in the fourteenth illustration to the Book of Job, or “A Song of Liberty,” and the Four Zoas IX: 308, etc., seems to indicate Blake’s anticipation of an ultimate reconciliation. To paraphrase, “at that time,” the Sons of Urizen shall shout and Urizen-Apollo regain the plow-chariot, refurbished by the Sons, and drawn by the Horses of Instruction formerly seen raging in Orc’s Cave, and off will go Urizen-Apollo in the chariot Love to plow up the universe preparatory to the final harvest.

What Blake seems to be saying is that only when all “True Believers” in this, that, or the other “school” or approach shall let go of their devotion to arbitrary positions and open up to the totality of the Cosmos and its Music shall they and Music itself experience the final harvest of potential Joy and Bliss. Each of us experiences the undifferentiated Innocence of childhood. We seek to cling to it and, entering into the problems presented by Experience, seek as well restoration of that State which in retrospect appears so much more felicitous than it may in fact have been. The Thels, the Hars and Hevas, the Professional Innocents, if you will, come to mind. Conversely, the Urizenic person struggles to bring the world of Experience under control by “bringing out of number, weight and measure.” Both are doomed to fail. As I “read” Blake’s visionary premise (or promise), the Horses of Instruction and the Tygers of Wrath must escape Luvah’s clutches and Orc’s Caves through the ending of each factional Emanation’s clinging to a conviction of total rectitude. Integration of the personality, or psyche, achievement of the State of Organized Innocence, consists essentially of the acceptance of Innocence’s regrettable but irrevocable loss coupled with Experience’s tedium, terror and pain, and facing Life in its totality as it is, unconditionally loving it with the hopeful openness of the State of Innocence. Only when all of the individuals making up mankind have arrived at this State shall Man, or Albion, be ready for the next progression. Then Man, now bemused, inert, bereft of what Music released could bring to the psyche, would be “plowed”—ravaged by Music, as by all of the Arts. What mankind should seek, it appears, is “Progression,” becoming rather than mere being. It is obvious that this is not to be accomplished without Contraries, which must be welcomed if there is to be Progression.

Melody is the basis of all lasting Music. In nearly four decades of singing, in just about every area of possible performance from jazz to classical concertizing and opera, I have yet to hear of a singer capable of singing chords. It seems reasonable to assume that music began with the solo human voice. The addition of other voices, consonant or dissonant, human or instrumental, has only added emotional emphasis or embroidery to Melody. The most successfully memorable symphonic writers have recognized and catered to this atavistic need for Melody which evokes response in the listener’s soul. A composition which incorporates no patterns with recognizable relation to some human response expresses nothing. Such a composition would be, and is, nothing more than a “bringing out of number, weight and measure,” and a mathematical diddle. It would surely not qualify as representative of “one of the three Powers in Man of conversing with Paradise, which the Flood did not Sweep away” (A Vision of the Last Judgment, K 609). Yet there has been an enormous amount of such alleged music presented to the world by pedants along the way, counterbalancing the superfluity of abominations called “free music.” Is not the operative word in Blake’s condemnation of Harmonies, “paltry”?

In the reviews of Blakean music which follow I find it impossible to state categorically that any given composition is “true to Blake,” for I am certain that each composer was seeking to be open to the two Contraries as I have tried to define them. They are, in sum, my own entirely subjective appraisals.

I shall not review Allen Ginsberg’s recording of Songs of Innocence and Experience (MGM-Verve FTS-3083), begin page 93 | ↑ back to top since it was exhaustively and well reviewed in Blake Newsletter (I will confess that my copy of the recording is nearly worn through.) Nor do I feel that my competence extends to either the Fugs’ or the Doors’ recordings. What follows is based upon such material as I have been able to locate in the Los Angeles area in the fall of 1973. I have ordered further items. Any assistance from readers through the lending of items listed in Bentley and Nurmi’s Blake Bibliography or Blake Newsletters 14 and 19 but (some of them long) out of print would be much appreciated.

Before turning to recordings or to music intended for performance, I should like to consider a book of settings intended for the amateur singer: Songs of Innocence, William Blake, music and illustrations by Ellen Raskin, guitar acc: Dick Weissman (Garden City, N. Y.: Doubleday, 1966. LC Card No. 66-11658). I was only able to obtain a copy of this book on loan from a friend of a friend. If the latest Books in Print is valid, Ms. Raskin’s book is out of print, which is unfortunate. As a book, it is handsomely executed, beautifully bound to lie flat easily on a music-rack. Each Song is illustrated appropriately in colored woodcuts by Ms. Raskin. Simplicity is the keynote of the melodies and accompaniments. In fact, the Preface states that they were composed to be “playable by second grade piano students.” The tunes are not especially memorable—perhaps they would be for a child—but they are easily within the capabilities of a child’s voice between 6 and 12, and are, as well, appropriate to the texts. Perhaps a bookshop may still have a copy out back, or a copy might be found in a used-book store. For Blake-lovers with children, or Innocents with limited pianistic ability and vocal agility, it is well worth looking for.

Five William Blake Songs, Op. 66, by Malcolm Arnold, for contralto and string orchestra (London: British & Continental Music Agencies, 1966, 64 Dean St., London W.I.), are quite lovely and appropriate tunings. The texts of the five songs are excerpted from Blake’s Poetical Sketches. The first is “O Holy Virgin! Clad in Purest White” (“To Morning”); II, “Memory, Hither Come”; III, “How Sweet I Roamed”; IV, “My Silks and Fine Array”; and V, “Thou Fairhair’d Angel of the Evening” (“To the Evening Star”). The group as it stands would make a worthy addition to an orchestral concert for any contralto. How well they would work with piano reductions as accompaniments for recital purposes is not certain, since so much of a composer’s intent is lost in such translation. I’d love to hear Jessye Norman sing them!

In terms of simplicity, or relative ease of execution, and yet appropriateness to the text, Gardner Read’s “Piping Down the Valleys Wild” (Op. 76, no. 3, piano accomp., Galaxy Music Corp., New York, 1950) very nearly falls within the same category as Ms. Raskin’s collection. It would be worthy of inclusion in a recital program, as it succeeds in avoiding the dangers of preciosity.

Virgil Thomson’s Five Songs from William Blake (G. Ricordi, New York, 1953) to me seems contrived for the sake of contrivance, complex for the sake of complexity and, for modern tastes, redolent of the period between World Wars when arty songs were written under the guise of art songs. The most vivid example of this is No. 2, “Tiger! Tiger!” which for some unfathomable reason has an accompaniment somehow suggestive of jungle telegraph drums. Thomson’s setting of “The Little Black Boy” strikes me as a bit of the “Shortnin’ Bread” genre, undercutting Blake’s intentions. The five settings are difficult of execution for singer and accompanist. The remaining three songs include “The Divine Image,” “The Land of Dreams” (Pickering MS., K 427), and “And did those feet” (Milton, Preface, K 480). The last-named suffers unavoidably in comparison with Sir C. Hubert Parry’s majestic hymnic setting known as “Jerusalem.” In toto, in this group, the texts are undeniably Blake’s but oh! those paltry Thomson harmonies!

Which brings me to “one of Albion’s Sons . . . who creates . . . by Harmonies of Concords & Discords Opposed to Melody.” Benjamin Britten’s Songs and Proverbs of William Blake, for Baritone and Piano, op. 74 (London, Faber and Faber; New York, G. Schirmer, 1965), is available on London OS 26099, joined on the reverse of the recording with Britten’s settings of Donne’s Holy Sonnets. Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau sings the Blake, Peter Pears the Donne, with Britten himself accompanying both at the piano. According to the notes on the recording envelope, Pears, current tenor assoluto of British music, selected the Blake texts

to form a cycle [intended to be] performed without a break. Six Proverbs of Hell act as musical ritornelli between six Songs of Experience, and a final ritornello, an aphorism from Auguries of Innocence, leads into the last song, taken from the same set. Verbal cross-references between proverbs and songs are many, but musically the songs appear self-contained, while the proverb-ritornelli plainly develop one idea across the work. This is itself an aphorism, all twelve notes arranged as three four-note segments (E-D#-D b -G; C#-C b -B-F#; B b -A-G#-F); within the segments note-orders are variable and such twisting chromatic shapes as D#-E-D b acquire a motivic significance that extends into the songs.

The textual arrangement, as credited to Pears, is well thought out, considering its stated purpose:

| 1: Lines 2, 3, 4 & 5 from the Proverbs of Hell, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, Plate 8, K 151 | 1: “London,” S of E, K 216 |

| 2: Line 1, same | 2: “The Chimney Sweep,” S of E, K 212 |

| 3: Line 11, same | 3: “A Poison Tree,” S of E, K 218 |

| 4: Line 2, Plate 9, same, K 152 | 4: “The Tyger,” S of E, K 214 |

| 5: Line 5, Pl. 9, K 152, same Line 18, Pl. 7, K 151, same Line 13, Pl. 9, K 152, same | 5: “The Fly,” S of E, K 213 |

| 6: Lines 12, 11, & 10, Plate 7, K 151 | 6: “Ah, Sun Flower,” S of E, K 215 |

| 7: First 4 lines of “To See a World,” from “Auguries,” K 431 | 7: “Every Night & Every Morn” line 119, K 433, & line 132, K 434 |

The cycle is intended as an evocation of the State of Experience, according to the liner notes. If it were performed in a recital hall “without a break,” it would succeed far beyond the composer’s intentions, because it is tedious, terrifying, and filled with the pain of Urizenic contrivance. Newtonian, perhaps; Blakean, never. I cannot but classify it as a wondrous example of Blake’s intended target for “bringing out of number, weight and measure,” and an esoteric, precious, in-joke sort of thing, dear to the heart of that one individual in 100,000 or more who has a Ph.D. in Musicology, with Absolute Pitch thrown in. Not a single “national melody” or any other sort of “melody” except those accidents in the mathematical formulae—are they meant to stand for Orcan flames?

A few of the individual settings strike me as interesting and useful, worth a recitalist’s effort to prepare for inclusion on a program as curiosa: “A Poison Tree,” “The Tyger,” “The Fly,” and the concluding pairing, a combination of “To See a World” with “Every Night and Every Morn.” But the entire cycle as a totality, a “group”? Thank you, no.

On the recording Fischer-Dieskau performs masterfully, with his usual impeccable musicianship and vocal technique. According to the liner notes, once more, the Blake settings were put together and composed with Fischer-Dieskau in mind.

In approaching the compositions of Ralph Vaughan-Williams intended as musical settings of Blake texts, one does so with almost the reverential sense of awe that staunch Anglo-Catholics feel towards the Apostolic Succession. Both of Vaughan-Williams’s Blake works were “commissioned,” in a sense, to celebrate dates related to Blake’s life.

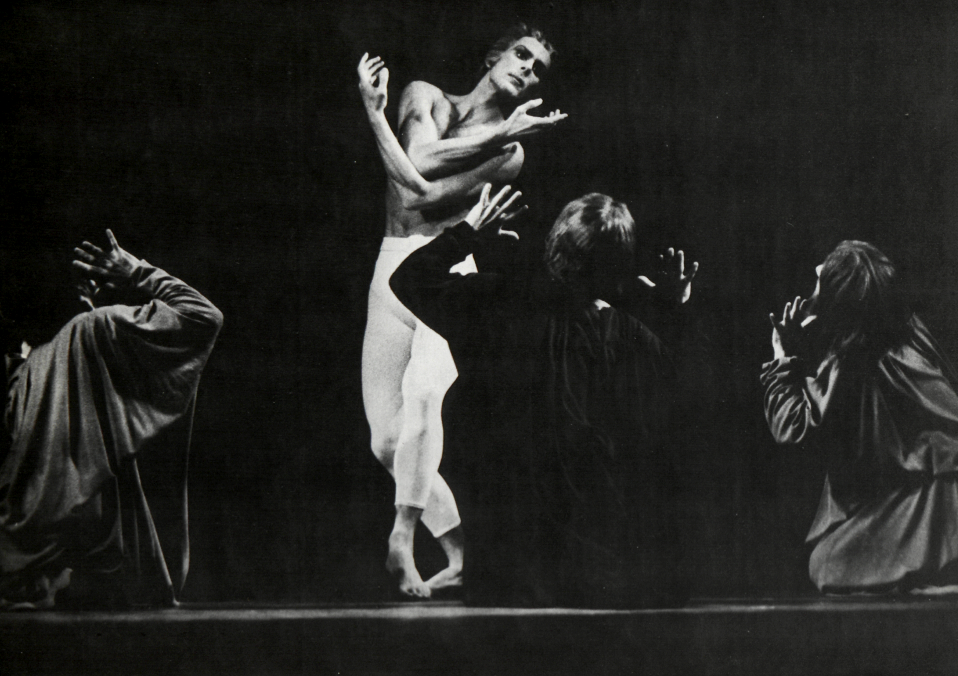

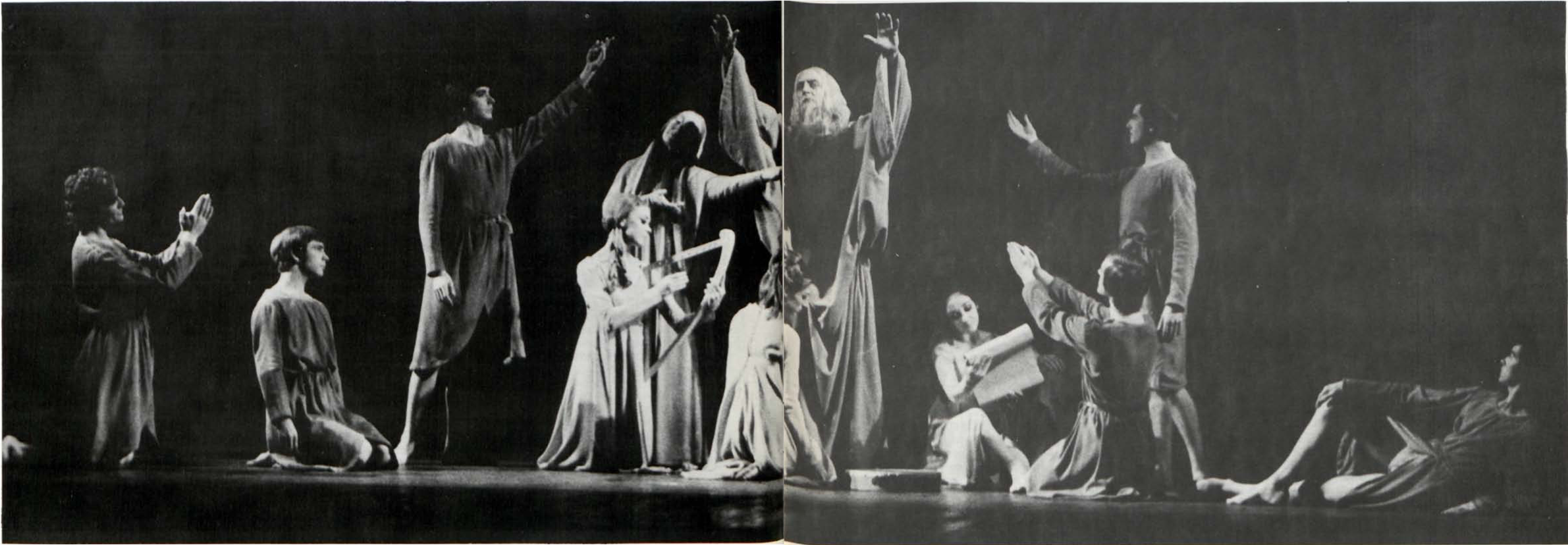

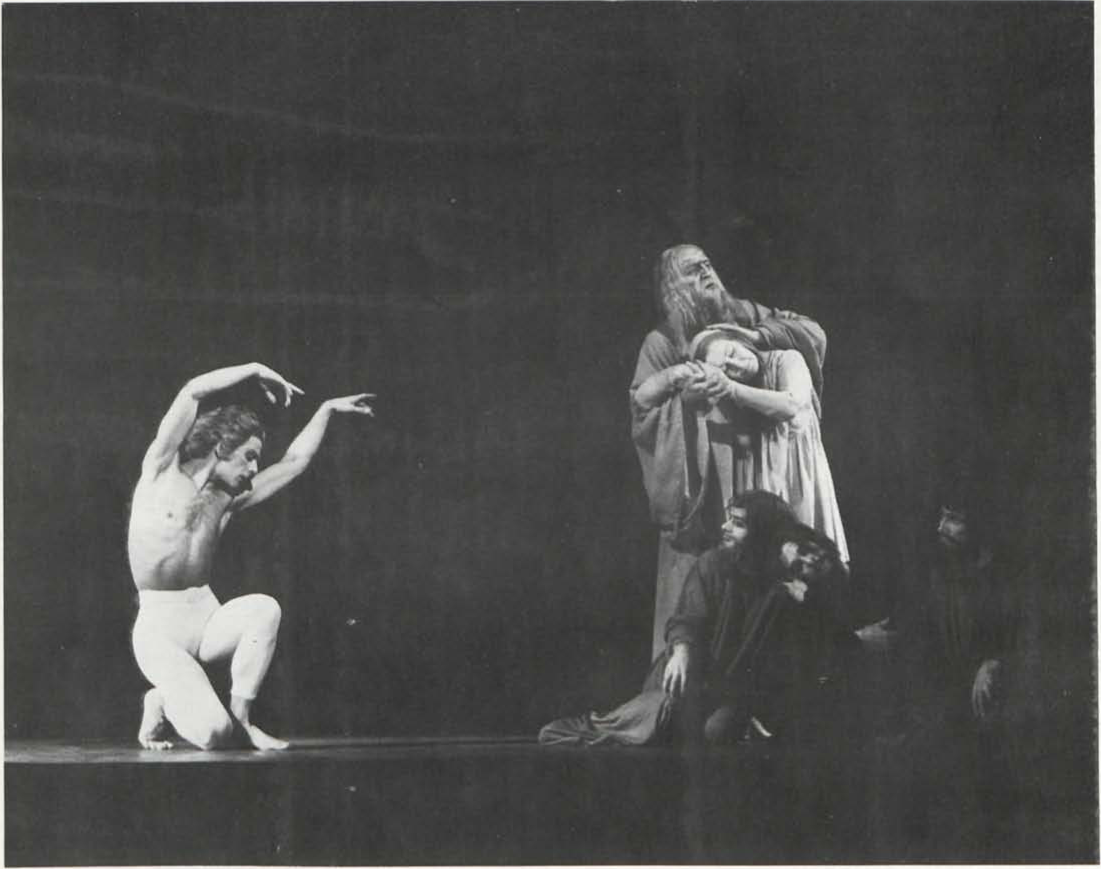

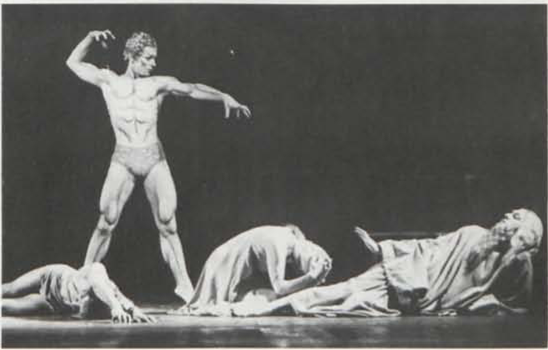

begin page 95 | ↑ back to top Job, a Masque for Dancing, which may be considered either as ballet music or as a symphonic poem, was composed to celebrate the centenary of Blake’s death in 1927. Ten Blake Songs (Oxford Univ. Press, 1958) were written for the film, The Vision of William Blake, at the request of the Blake Society Bicentenary Committee.The scenario for Job was written by Sir Geoffrey Keynes, who based the ballet on Blake’s Illustrations to the Book of Job. Keynes’ sister-in-law, Mrs. Gwendolyn Raverat, assisted in condensing Blake’s twenty-one illustrations into eight scenes. In turn, scenario in hand, they approached Mrs. Raverat’s cousin Vaughan-Williams for the music. Vaughan-Williams agreed to collaborate, but insisted that the conception be that of a seventeenth-century masque, with dancing on point ruled out, rather than as a ballet. The resultant work is as much Vaughan-Williams’ as Sir Geoffrey’s and Mrs. Raverat’s, as he made some alterations to their scenario and added stage directions for the “masque.” However, it remains unerringly true to the Blakean Job. Musically speaking, Vaughan-Williams’ credentials as “English Vaughan-Williams” are about as impeccable as could be conceived. At the Royal Academy of Music, he was a pupil of Sir C. Hubert Parry, who was, in turn, composer of the setting of “Jerusalem” from Blake’s Milton and his time’s leading student and advocate of the English vocal traditions from their earliest recording. Parry’s mantle of specifically “English” musical expertise fell upon the shoulders of Vaughan-Williams. Thus, in coming to an auditing of this Job, we should expect to hear Blake’s concepts of Job organized by the chief expositor of Blake’s works and set to music by the chief expositor of England’s “national melodies” symphonically orchestrated. And we should not be disappointed. Even if one had never heard of Blake or his Job, the music as music stands as a tremendous work of symphonic creation. To be able to listen to it, conducted by Sir Adrian Boult, to whom Vaughan-Williams dedicated the work (on either the Angel recording, S-36773, list $5.98, or the Everest recording, SDBR-3019, list $4.98), with one’s copy of the Blake illustrations before one is an experience of great intensity. There is also an EMI recording, HQS-1236, not readily available in the U.S. (EMI and Angel are parent and offspring companies, respectively). Both the Angel and the Everest are still available at begin page 96 | ↑ back to top this writing. The latter I discovered locally in the heavily-discounted reissue label bins. The Angel recording’s envelope is illustrated with a reproduction of Blake’s “When the morning stars sang together,” and the reverse has the more copious notes of the two, by Michael Kennedy. The Everest’s cover bears a blow-up of Plate XXI from Blake’s Illustrations, with a color-overlay of rainbow hues, at the foot of which, tinted a devilish red is, apparently, a photo of some unidentified balletic Satan en couchant, looking up at the engraved Job.

There is no way of determining the dates upon which the recordings of Job were done, but I suspect the Everest is the older recording, possibly “re-channeled for stereo.” It is interesting that both recordings were under Sir Adrian Boult’s baton and yet how audibly different their overall “feel” comes through. Of course, this is not alone due to a difference in recording dates, but to a number of factors—differing personnel, concertmasters, and concepts of intonation, attack, etc. On the Everest, the London Philharmonic Orchestra attacks more cleanly and forcibly but with less smoothness of line and balance than the Angel’s London Symphony Orchestra. Perhaps the intent of the two recordings is the key. I suspect that the Everest was conceived as accompaniment to Job as “Masque for Dancing,” as ballet music, while the Angel was conceived as symphonic poem. Which the potential purchaser would prefer is a matter of individual taste, since both are excellent performances. Now, if only the Royal Ballet would bring a performance of Job to darkest Los Angeles!

I have attempted an analysis of the Keynes-Raverat-Vaughan-Williams Job scenes vis-à-vis Blake’s plates. Scene 1: Plates 1 and 2; Scene 2: Plate 2; Scene 3: Plates 2 and 3; Scene 4: Plate 3; Scene 5: Plate 4; Scene 6: Plates 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 and 11; Scene 7: Plates 12, 13, 14 and 15; Scene 8: Plates 14 through 20; Epilogue: Plate 21.

Vaughan-Williams’ Ten Blake Songs bring us back to settings of Blake texts for voice. The composer has specified them for either tenor or soprano, indicated which voice should sing which songs, and written the accompaniments to be played by a solo oboe, with three of the songs unaccompanied. The songs can be sung by either of the specified voices, though my preference would be a soprano for Songs 1 and 5. The composer’s own footnote says that “The oboe parts of these songs may, in case of necessity, be played on a violin or (by transposing the songs down a tone) on a B flat clarinet—but neither of these expedients is advisable. R. V. W.” A recorder, too, comes to mind. But do try to find an oboe-player. These are clean, simple-sounding modal tunes in the quality of the English folk idiom, Vaughan-Williams’ lifelong interest. The reed’s counter-melodies are delightful, with occasional dissonances seemingly occurring by accident as it weaves about the vocal line. The songs are not simple to execute, particularly to perform with the effect of simplicity they demand, as the performers on the only American-made recording I have found must have discovered. The Songs set are as follows:

| 1. | “Infant Joy” (S of I) | Tenor or soprano and oboe |

| 2. | “A Poison Tree” (S of E) | Tenor and oboe |

| 3. | “The Piper” (S of I) | Tenor or soprano and oboe |

| 4. | “London” (S of E) | Tenor unaccompanied |

| 5. | “The Lamb” (S of I) | Tenor and oboe |

| 6. | “The Shepherd” (S of I) | Tenor or soprano unaccompanied |

| 7. | “Ah: Sun Flower” (S of E) | Tenor and oboe |

| 8. | “A Divine Image” (S of E) | Tenor or soprano and oboe |

| 9. | “The Divine Image” (S of I) | Tenor or soprano unaccompanied |

| 10. | “Eternity” (Notebook K 184) | Tenor or soprano and oboe |

The American-made recording referred to above is Desto DC-6482, mono $4.95, stereo $5.95. The record’s reverse includes Vaughan-Williams’ settings of A. E. Housman’s “Along the Field” and of Chaucer’s “Merciless Beauty,” all performed by Lois Winter, soprano, and John Langstaff, baritone, with Ronald Roseman accompanying the Blake songs on oboe. The musicianship of the performers is beyond reproach, a prerequisite for the performance of the songs. Ms. Winter sings professionally and musically with smooth line. “The Shepherd,” as she performs it, is the high spot of the recording. But, alas, John Langstaff. His efforts are noble, but give me my reason for emphasizing earlier that the composer was correct in specifying that the songs be sung by either a soprano or a tenor. The gradation between a high baritone and a dramatic tenor (or so-called lyrico-spinto) may seem slight to an untutored ear, but this recording can provide an example of almost overtly didactic power for that ear. A singer’s attempts at delineation of emotional States should not include his obvious anxiety at being able to negotiate high passages, made obvious by unfocused bellowing. One’s audience should not be made conscious of technique, or lack of it.

Happily, two other recordings of the Vaughan-Williams Ten Blake Songs are available, though both are imports, which may make finding them more difficult; they are sung by appropriate voices and I suspect as Vaughan-Williams intended that they be sung. These are: Robert Tear, Philip Ledger, Piano, Vaughan-Williams Songs of Travel, Blake Songs, Etc., (Argo ZRG 732, Argo Div., Decca Recording Co., Ltd., 115 Fulham Road, London, SW3 6RR), and Vaughan-Williams, On Wenlock Edge, Ten Blake Songs, Etc., Ian Partridge, The Music Group of London, Janet Craxton, Oboe, Jennifer Partridge, Piano (EMI HQS begin page 97 | ↑ back to top

1236, EMI Records, Hayes, Middlesex, England). Both list for $5.95.Both of these recordings deserve highest marks, the tenor voices of Mr. Tear and Mr. Partridge differing only in their innate qualities. Mr. Tear’s voice has a bit darker timbre, while Mr. Partridge’s is more lyric. On both recordings, Blake’s Songs are accompanied by solo oboe when indicated, the added instruments being for the other listed material. The oboist on the EMI recording, Janet Craxton, was the oboist whom Vaughan-Williams had in mind when he composed the songs and, to my ear, at least, does the more felicitous work in performance; Neil Black, oboist on the Argo recording, receives minor billing but is nonetheless excellent. As far as the singing of the Blake Songs is concerned, I can state no preference for one tenor’s performance over the other. The choice between the two recordings, if one must be made, must lie with the other Vaughan-Williams song material found upon them. Mr. Tear delivers the Songs of Travel so gorgeously that I, a fellow-tenor, was in tears at auditing them, and not alone were they tears of envy! Yet, Mr. Partridge no less consummately presents the A. E. Housman On Wenlock Edge cycle. Both perform The Water Mill, and differing additional songs. If you can afford it, buy them both!

My pursuit of settings of Blakean texts to music has provided me with a number of unexpected rewards, and high among them has been the discovery of one particularly well-done group of songs by an American composer, Nicholas Flagello. Professor Flagello composes, conducts, and teaches at Manhattan School of Music and at Curtis Institute. His compositions of interest here are settings of songs from An Island in the Moon (published by General Music Publishing Co., Inc., P. O. Box 267, Hastings-on-Hudson, N.Y. 10706). A handsomely produced recording of the songs is available by mail as The Music of Nicholas Flagello—4, Serenus recording SRS 12005, from Serenus Corp., at the same address as General Music Publishing Co., for $6.95. The reverse side of the recording is a performance of Flagello’s Contemplazioni di Michelangelo, all of the songs sung by Nancy Tatum, soprano, accompanied by members of the Orchestra begin page 98 | ↑ back to top Sinfonica di Roma, conducted (and apparently orchestrated) by the composer, Flagello. Ms. Tatum, an American expatriate with a well-established European name, sings gorgeously; the accompaniment and its execution combine with her singing to give what David Frost might call a delicious experience. These are the compositions of a modern master, not stalled in any ephemeral school, but combining effortlessly every compositional technique. In another sense, the recording achieves another “Marriage,” in that Blake’s texts are juxtaposed on one recording with those of one of his heroes, Michael Angelo! The Blake songs as sung by the various participants in Island in the Moon’s floating salons, are:

| “As I Walked Forth” (K 55) | Steelyard, the Lawgiver |

| “This Frog He Would” (K 55) | Miss Gittipin |

| “O Father, Father” (K 60) | Quid |

| “Good English Hospitality” (K 58) | Steelyard |

| “Leave, O Leave Me” (K 61) | Miss Gittipin |

| “Dr. Clash and Signior Falalasole” (K 61) | Scopprell |

For a mezzo- or dramatic soprano, or dramatic tenor, these songs are the sort that one seeks but rarely finds, full of Melody and with not a single Paltry Harmony in the accompaniments that I can detect. But performers would be hard-pressed to excel the performances on this recording!

Surely, “music heard so deeply / That it is not heard at all, but you are the music / While the music lasts” (T. S. Eliot, “Dry Salvages”) is what every composer, whether Innocent, Experienced, or with Innocence Organised, tries, hopefully, to hear, perform, create, re-create, compose on paper, etc., whether in pure melodic line, with melismatic embroidery, in elementary counterpoint, or with the most complex harmonic progressions and orchestration.

A Checklist of Musical Settings of Blake

Two kinds of material are included in the list: first, marked +, the scores and phonograph records I have reviewed above; second, marked *, items that (as far as I know) have not been listed in any checklists of Blake settings. Some of the new listings are taken from Sergius Kagen’s Music for the Voice, rev. ed. (Bloomington, Ind.: Indiana Univ. Press, 1968), and appear as listed in that work.MUSICAL SCORES

| + Arnold, Malcolm | William Blake Songs. Five William Blake Songs, op. 66, for contralto and string orchestra. London: British and Continental Music Agencies, 1966. |

| + Britten, Benjamin | Songs and Proverbs of William Blake, for Baritone and Piano, op. 74. London: Faber and Faber; New York: G. Schirmer, 1965. |

| +*Flagello, Nicholas | An Island in the Moon. Six songs for soprano or tenor, piano acc., General Music Co., Inc., P.O. Box 267, Hastings-on-Hudson, N.Y. 10706, 1965. Published separately as follows: |

| “As I Walked Forth” $1.00, “Dr. Clash and Signior Falalasole” $1.50, “Good English Hospitality” $1.50, “Leave, O Leave Me” $1.50, “O Father, Father” $1.25, “This Frog He Would Awooing Go” $1.00 | |

| * Griffes, Charles | In a Myrtle Shade, G. Schirmer, N.Y. n.d. |

| * Kagen, Sergius | London and Memory Hither Come, medium voices, Mercury Music Corp., N.Y. n.d. |

| * Kupferman, Meyer | Three Songs of Blake, for voice and clarinet, General Music Publishing Co., Inc., P.O. Box 267, Hastings-on-Hudson, N.Y. 10706, 1973. $1.50. Photo-off-set manuscript of group, written. in Neume form, that is, non-specific notation, with squiggled lines indicating suggested rise and fall of voice and instrument ad libitum. |

| * Quilter, Roger | Dream Valley, one of “Three Songs of William Blake,” Winthrop Rogers. n.d. |

| + Raskin, Ellen | Songs of Innocence [by] William Blake. Music and illustrations by Ellen Raskin. Guitar arrangements by Dick Weissman. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1966. |

| + Read, Gardner | Piping Down the Valleys Wild, op. 76, no. 3, piano acc., Galaxy Music Corp., N.Y., 1950. |

| +*Thomson, Virgil | Five Songs from William Blake, G. Ricordi, N.Y., 1953. |

| “And Did Those Feet,” “The Divine Image,” “The Little Black Boy,” “The Land of Dreams,” “Tiger! Tiger!” | |

| +*Vaughan-Williams, Ralph | Ten Blake Songs, for voice and oboe. Oxford University Press, 44 Conduit St., London W. 1, 1958. $3.50. (New listing of score.) |

| “Infant Joy,” “A Poison Tree,” “The Piper,” “London,” “The Lamb,” “The Shepherd,” “Ah! Sun-Flower,” “Cruelty has a Human Heart,” “The Divine Image,” “Eternity” |

PHONOGRAPH RECORDS

| * Axelrod, David | Song of Innocence (arrangements for orchestra). Capitol ST 2982 (“A suite in seven parts inspired by the writings of William Blake.”), $5.95. No longer listed in Schwann. |

| + Britten, Benjamin | Songs & Proverbs of William Blake, Op. 74, The Holy Sonnets of John Donne, Op. 35. Peter Pears, tenor (Donne), Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, baritone (Blake), and Benjamin Britten, piano. London OS 26099, $5.95. |

| +*Flagello, Nicholas | Six Songs from An Island in the Moon, Contemplasione di Michelangelo, issued as The Music of Nicholas Flagello—4, Nancy Tatum, dramatic soprano, with Flagello conducting the Orchestra Sinfonica di Roma. $6.95 by mail from Serenus Corp., P.O. Box 265, Hastings-on-Hudson, N.Y. 10706. SRE 1005 (Mono), SRS 12005 (Stereo). |

| * Parry, Sir C. Hubert | “Jerusalem” (“And did those feet in ancient time”) in The Last Night of the Proms. BBC Symphony conducted by Colin Davis. The previously issued recording of a Last Night at the Proms (Philips 6502 001) was recorded in 1969. Recorded in 1972, Philips’ (6588 011) new Proms recording duplicates only two items from the previous issue, the “Jerusalem” and “Pomp and Circumstance.” And, of course, “God Save the Queen.” The newer recording comprises less overtly “British” music than the older, replacing Elgar’s “Cockaigne” op. 40 and Wood’s “Fantasia on British Sea Songs” with Berlioz, Wagnerian (Wesendonck) Lieder sung magnificently by Jessye Norman, a mock operetta and an audience-participation battle scene, etc. Both are marvelously tumultuous recordings. |

| + Vaughan-Williams, Ralph | Job, A Masque for Dancing, London Philharmonic, Sir Adrian Boult, conducting. Everest SDBR 3019, $4.95. |

| + | Job, A Masque for Dancing, London Symphony, Sir Adrian Boult, conducting. Angel-EMI S-36773, $5.95. |

| + | Three Song Cycles. Includes Ten Blake Songs, Lois Winter, soprano, John Langstaff, baritone, and Ronald Roseman, oboe. Desto DC 6482, $5.95. |

| +* | On Wenlock Edge, Ten Blake Songs, The New Ghost, The Water Mill. Ian Partridge, tenor, The Music Group of London, Janet Craxton, oboe, Jennifer Partridge, piano. EMI Odeon HQS 1236, $5.95. This recording previously listed as including the Blake Songs and the Angel recording of Job above. EMI seems to have made changes. |

| +* | Songs of Travel, Linden Lea, The Water Mill, Ten Blake Songs, Orpheus with his Lute. Robert Tear, tenor, Philip Ledger, piano, Neil Black, oboe. Argo ZRG 732, $5.95. |