article

begin page 166 | ↑ back to topSome Sexual Connotations

The last time I taught “To Spring” in California, three students walked out of the class—dramatic confirmation, perhaps, that the poem suggests a correspondence between dew and other genital juices, semen especially: “O thou with dewy locks . . . . Come o’er the eastern hills . . . . scatter thy pearls / Upon our love-sick land.”1↤ 1 Blake is quoted from David V. Erdman, ed. The Poetry and Prose of William Blake, 3rd printing, rev. (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1968). Spring’s “dewy locks” are like those of the “beloved” in the Song of Songs, who says, “Open to me, my sister, my love, my dove, my undefiled: for my head is filled with dew, and my locks with the drops of night” (5:2). For the ancient Greeks, dew was a manifestation of Zeus’ semen;2↤ 2 Géza Róheim, Animism, Magic, and The Divine King (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner[e] & Co., 1930), p. 95. so Emile Benveniste can discuss lexical relationships in Greek which suggest that “tiny new born animals are like dew, the fresh little drops which have just fallen,”3↤ 3 Indo-European Language and Society, trans. Elizabeth Palmer (London: Faber & Faber, 1973), p. 22. and William Harvey can equate dew with “the Primigenial Moisture” from which “Seed” is made.4↤ 4 Anatomical Exercitations Concerning the Generation of Living Creatures, trans. (London, 1653), pp. 462-63. This equation is explicit in Jerusalem 30[34].3-4: “O how I tremble! how my members pour down milky fear! / A dewy garment covers me all over, all manhood is gone!” By the end of “To Spring,” Spring has already come (see OED citations from 1650 and 1714), and so quickly that the speaker is left pointing to the country’s arborescent “modest tresses” which were bound up.

With “To Summer” things get even hotter as we focus on the presence of Summer in the countryside, notably in “our vallies,” “our mossy vallies”: “Our vallies love the Summer in his pride” (1, 10, 13). We encounter similar content in the “sweet valleys of ripe virgin bliss” and “valleys of delight” of the Lambeth books (Am c. 30; SL 3.28), evoking, perhaps, the popular etymology, “Vulva, as it were vallis, a valley.”5↤ 5 Helkiah Crooke, ΜΙΚΡΟΚΟΣΜΟΓΡΑΦΙΑ, A Description of the Body of Man (London, 1651), p. 175. Such contentment often befalls in the summer, and Summer “oft . . . has slept, while we beheld / With joy [his] ruddy limbs and flourishing[e] hair.” Our joy, or jouissance, is that of gratified desire, and it allows us to turn to making songs and using other instruments of joy—in accordance with the notebook quatrain:

Abstinence sows sand all overSuch gratified desire is not the lot of the singer who sweetly “roam’d from field to field / And tasted all the summers pride” until he had the misfortune of beholding not the ruddy limbs of Summer but “the prince of love” (Amor does not roam). In a double bind of lilies and “blushing” (e-)roses, the singer forsakes wide open fields for the vita nuova of love’s cultivated gardens and golden pleasures. Entering the garden, everything seems permitted: “With sweet May dews my wings were wet.” But the sweet wetness of what one may do in the warmer months evaporates as Phoebus fires “vocal rage” and the singer, now come of age, is caught and caged. Another of Blake’s singers feels that whenever he enters the “sweet village” where his “black-ey’d maid” is sleeping, “more than mortal fire / Burns in my soul, and does my song inspire.” Just so the first singer now spends his time alone with a prince of love who loves songs first, then “sport and play,” and who will at last only mockingly stretch out the singer’s now solitary golden wing.

The ruddy limbs & flaming hair

But Desire Gratified

Plants fruits of life & beauty there

(E 465)

That Blake’s “loom” also invokes the “womb” is well recognized; Jerusalem even repeats on three occasions that “the female is a golden Loom.” The Looms are a main feature of “Cathedron,” the textile-mill district of Golgonooza. With its spires and domes Cathedron obviously owes something to “cathedral”—which as a “holy place” also names the female genitalia, the “holy of holies” as a common vulgarism had it—but even more interesting is the word’s closeness to the name of the women in Blake’s life, his mother, sister, and wife, Catherine. Blake surely knew that the name comes from the Greek “katheros,” meaning “pure.” In The Four Zoas Enitharmon erects Looms, “And calld the Looms Cathedron in these Looms She wove the Spectres / Bodies of Vegetation” (100.3-4). There

The Daughters of Enitharmon weave the ovarium & the integument“Ovarium” is a curiously technical word to find here, just as “lascivious delight” seems an unusually strong description, though we hear elsewhere of the “sweet intoxication” in which the Daughters ply their looms (J 80.80). Going to the Authorized Version and to the Hebrew rachamim, “bowels” can also mean “womb,” and Jerusalem tells us that drawn silk can be a sexual “silk of liquid . . . issuing from . . . Furnaces” (87.19-20). This system can be better understood if we grasp the sexual aspect of “fibres,” suggested parenthetically by Jean Hagstrum some years ago.6↤ 6 “Babylon Revisited, or the Story of Luvah and Vala,” in Stuart Curran and Joseph Anthony Wittreich, Jr., eds., Blake’s Sublime Allegory: Essays on The Four Zoas, Milton, Jerusalem (Madison: Univ. of Wisconsin Press, 1973), p. 107.

In soft silk drawn from their own bowels in lascivious delight

With songs of sweetest cadence

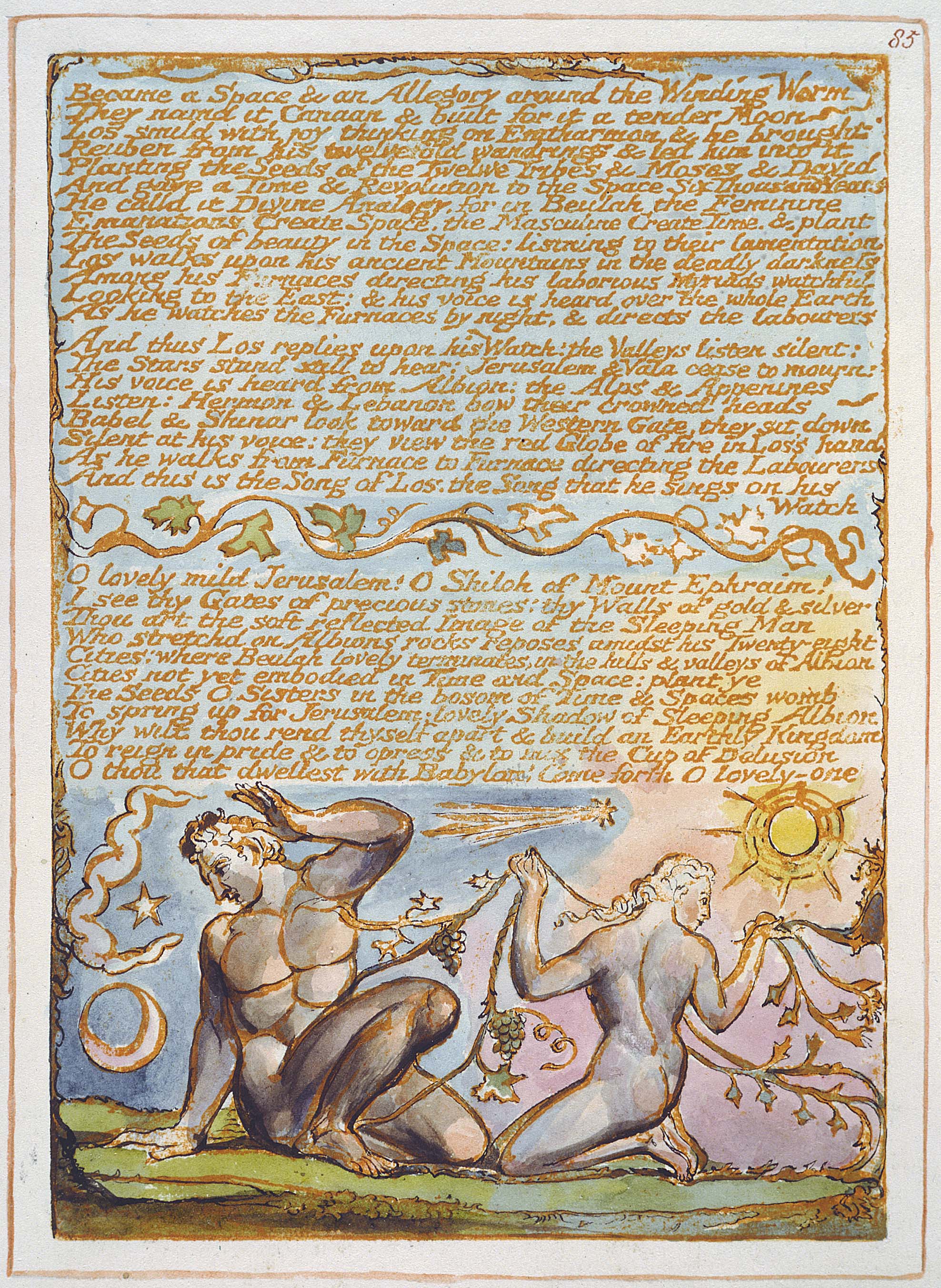

The correlation linking fibres, worms, and semen has one source in Erasmus Darwin’s influential hypothesis that begin page 167 | ↑ back to top life originates as a “simple living filament . . . an extremity of a nerve” which is secreted from the parent.7↤ 7 Zoonomia, or the Laws of Organic Life, vol. 1 (London: J. Johnson, 1794), p. 489. This “filament” could in turn be seen as an instance of “the seminal worms, now so well known [which] were first observed in the male seed by the help of the microscope.”8↤ 8 Albrecht von Haller, First Lines of Physiology, trans. William Cullen, The Sources of Science, no. 32, 2 vols. in 1 (1786); facs. rpt., New York: Johnson Reprint, 1966), sect. 882. So Orc “like a Worm / In the trembling womb / To be moulded into existence” (BU 19.21-23),9↤ 9 G. L. Leclerc de Buffon observes in his Natural History, General and Particular that “the spermatic worm . . . becomes a real foetus” (trans. William Smellie, 3rd. ed., 9 vols. [London, 1791], 2.137). appears to be, in part, a materialization of Los’ spermatozoon—a vermicular fibre. Ejaculation thus consists in “shooting out”—another common street term (“shooting out in sweet pleasure” [J 88.28])—fibres, or, giving the Female Will a superior position, in having fibres “drawn” out. In Jerusalem we see Enitharmon like a faint rainbow waving before Los and “Filling with Fibres from his loins which reddend with desire” (J 86.51), and in the illustration of plate 85 (illus. 1), one of the fibres handled by the naked Enitharmon leads, evidently, between Los’s thighs to his phallos—perhaps the propensity of semen to agglutinate into tenuating strands when handled is one source of its conception as silky “fibre.”

Again, when the Daughters are pulling fibres from Albion, as they do all through Jerusalem,

Conwenna sat above: with solemn cadences she drewPartridge’s Dictionary of Slang reports that “bone” was cockney slang for the erect penis beginning in the mid-nineteenth century,10↤ 10 Eric Partridge, A Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English, 5th ed. (New York: Macmillan, 1961), s.v. but that is for printed reference, which always lags far behind oral speech. Again, at the end of Jerusalem we see Los, himself now “intoxicated,” saying

Fibres of life out from the Bones into her Golden Loom

(J 90.21-22)

. . . my wild fibres shoot in veinsThis saturation of sexual reference suggests that Los is being enclosed in genitality, becoming a sort of polyphallos (to keep up with the polypuss) with proliferating “nervous Limbs” and “roots.”11↤ 11 “Nerve” is frequent in Latin for the penis (nervus), and so used in English by Dryden; this sense appears in Urizen’s address to the “bowstring” (one of the word’s other meanings) taken from the “serpent”: “O nerve of that lust form’d monster” (BA 3.27). In other contexts Blake refers to “the sportive root” and the “delving root,” and, in particular, we see the force of Orc as “Enitharmon cried upon her terrible Earthy bed / While the broad Oak wreathd his roots round her forcing his dark way” (FZ 98.7-8). Los says that men “know not why they love,” and that their misguided idea of “Holy Love” has “separated the stars from the mountains: the mountains from Man / And left Man, a little grovelling Root, outside of Himself” (J 17.31-32). Los next words are curious in the extreme:

Of blood thro all my nervous limbs. soon overgrown in roots

I shall be closed from thy sight.

. . . seize therefore in thy handWho is to draw out what in pity? Are the fibres to run on Enitharmon’s bosom as before “All day the worm lay on her bosom” (BU 19.24)? The passage is striking for the merely suggested quality of a graphic sexual reference. This is perhaps as Blake would have it: actual sexual relations cannot in the first instance fully image imagination, and in the second could not describe the nature of the intercourse between the Daughters and Albion, or Enitharmon and Los. As Los continues, “I will fix them / With pulsations. we will divide them into Sons & Daughters.” Division is always sexual: into parts, sections, sects, as the Latin etymology reminds us.

The small fibres as they shoot around me draw out in pity

And let them run on the winds of thy bosom

(J 87.5-9)

Having alluded to coitus interruptus,12↤ 12 Leopold Damrosch, Jr. argues that “Blake . . . dreads [sexual desire’s] power because it leads to generation,” and suggests that “We cannot be surprised if at times Blake suggests that the proper response is to withold the desired seed” (Symbol and Truth in Blake’s Myth [Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press, 1980], p. 203). it would be fitting to mention Blake’s conception of consummation. The word is polysemous: Frye notes its ambiguity “in referring to the two chief aspects of the Last Judgment, the burning world and the sacred marriage.”13↤ 13 Northrop Frye, Fearful Symmetry: A Study of William Blake (1947; rpt., Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press, 1969), p. 351. But since Jerusalem calls “the Loins the place of the Last Judgment” (44[30].38), consummation surely refers to profane marriage as well. Such consummation, it must be observed, is rather futile in Blake: while Orc’s parents hope “to melt the chain of Jealousy, not Enitharmons death / Nor the Consummation of Los could ever melt the chain.” Here the standard English sexual euphemisms “death” and “melt” point to the physical nature of the consummation. The chain cannot be melted because it is already part of the body of Los—his phallos is one of the chain’s essential links, as apparent in some versions of Urizen, pl. 21. Along with the male-female dialectic, there appear to be two kinds of consummation. “No one can consummate Female bliss in Los’s World without / Becoming a Vegetated Mortal, a Vegetating Death” (J 69.30-31). Such, evidently, is Blake’s denigration of physical, “Female,” consummation. For male consummation we must turn to Milton and another odd episode in Orc’s dealings with the Shadowy Female. In The Four Zoas, we should first note, it is “in the

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

. . . Behold how I am & tremble lest thou alsoOrc’s sexual “rage” has now turned to an anger which inures him to sexual temptation—a heavy change from the conclusion to the foreplay of America, where Orc “seiz’d the panting, struggling womb” of the Shadowy Daughter. Orc’s anger comes from the realization that the “nameless shadowy Vortex” has become “Urizens harlot / And the Harlot of Los & the deluded harlot of the Kings of Earth” (FZ 91.14-15)—in other words, Mystery, the whore of Babylon, “With whom the Kings of the earth have committed fornication, and the inhabitants of the earth have been made drunk with the wine of her fornication” (Rev. 17:2).

Consume in my Consummation; but thou maist take a Form

Female and lovely, that cannot consume in Mans consummation

(18.27-29)

“Mans consummation,” apparently, is to be “consummated in Mental fires” (FZ 85.46), a cerebral destiny which insures against the possibility that “the Sexual Garments sweet / Should grow a devouring Winding Sheet,” that “Sexual Generation swallow up Regeneration” (“Keys to the Gates,” 25-26; J 90.37). On the other hand, plate 7 of Jerusalem exclaims:

O holy Generation! [Image] of regeneration!Blake’s anger, and the contention that “Humanity knows not of Sex,” may be located in his reaction against a Pauline world “Where a Man dare hardly to embrace / His own Wife, for the terrors of Chastity that they call / By the name of Morality” (J 44[30].33; 32[36].45-47). It is men who have created rape, fornication, and a “Female Will / To hide the most evident God in a hidden covert, even / In the shadows of a woman & a secluded Holy Place” (J 30[34].31-32).

O point of mutual forgiveness between Enemies!

Birthplace of the Lamb of God incomprehensible!

(65-67)

This dynamic can be approached through Robert Stoller’s recent argument that the underlying cause of sexual excitement is hostility: “it is hostility—the desire, overt or hidden, to harm another person—that generates and enhances sexual excitement. The absence of hostility leads to sexual indifference and boredom. The hostility of erotism [Stoller’s term] is an attempt, repeated over and over, to undo childhood traumas and frustrations that threatened the development of one’s masculinity or feminity.”15↤ 15 Sexual Excitement (New York: Pantheon, 1979), p. 17. This analysis-cum-male fantasy finds an analogue in Blake’s perception of “Spiritual Hate, from which springs Sexual Love” (J 54.12). For Blake, however, the threatening childhood traumas and frustrations that underlie any hostility and excitement are associated more fundamentally with growing up, particularly growing into the inner hormonal explosion of the world of generation, whose complications are exacerbated by the divisions of gender which are first and foremost culturally instituted. Blake, “Weeping over the web of life,” will not accept the basic structures of our experience, and asks us to do the same. As Damrosch notes unsympathetically, “there is no avoiding the realization that [Blake’s] ideal for human existence does away with human nature as poets have always described it” (p. 217). Stoller believes further that the hostility is in part expressed through the “mystery” of the body: “the mystery being managed emanates from sexual anatomy.” And, he continues, “The point is not simply that in the past a person was frightened by mystery but that, paradoxically, he or she is now making sure the mystery is maintained . . . if the appearance [what Blake would call the veil] of mystery does not persist, excitement will fade.” A similar understanding is the basis for Blake’s indignation. For Blake, the “Sexual texture woven” is the corollary of “the Veil of Moral Virtue, woven for Cruel Laws” which prompts the “eternal torments of love & jealousy.” Inexorably, “All the Jealousies become Murderous and unite together in Rahab / A Religion of Chastity,” an evolution clearly identified by Mary Wollstonecraft as well. In the sacred rites of Sexual Religion, “the Female lets down her beautiful Tabernacle: / which the Male enters magnificent between her Cherubim” (J 44[30].34-35), but from the perspective of Eden this is just the pompous High Priest entering an empty room behind the veil: a ritual of guilt and atonement rather than the delight of joy and at-one-ment. Paul Miner, in “William Blake’s ‘Divine Analogy’ ” (Criticism 3 [1963]: 46-61), is very good on such correspondences between Old Testament references and Blake’s sexual context, though his distinction between pompous Atonement and a selfless “propitiatory offering” of coitus seems problematic. What is to be propitiated? It may well be that “no one can consummate Female bliss . . . without Becoming a Generated Mortal,” but then, neither can we

behold Golgonooza without passing the Polypusbegin page 169 | ↑ back to top

A wondrous journey not passable by Immortal feet . . .

For Golgonooza cannot be seen till having passed the Polypus

It is viewed on all sides round by a Four-fold Vision

Or till you become Mortal & Vegetable in Sexuality

Then you behold its mighty Spires & Domes of ivory & gold

(M 35.19-25, italics added)

Jerusalem shows us “the beautiful Daughters of Albion,” and adds, “If you dare rend their Veil with your Spear; you are healed of Love!” (J 68.42). Set amidst graphic passages devoted to the castrating Druidic priestesses, this introduces a countervailing comment identifying phallic penetration with the soldier’s spear that pierced Christ’s side (John 19:34). The point may be to show that the “love” of which one may be healed, is, as elsewhere in the passage, pride & wrath; Los says, “I also have pierced the Lamb of God in pride & wrath” (FZ 106.55). Fallen sexuality is seen as inextricably bound up with the context of power, the hostile dehumanizing and fetishizing of the “sex-object.” Stoller’s argument that hostility underlies a prevalent experience of sexual excitement lends Blake’s image additional weight. In rending the veil one is healed of a wounding “love” to become, perhaps, like Bromion sated and bored after having rent Oothoon’s virgin mantle with his thunders (a scene offering another reference to the Passion and its aftermath). Or, paradoxically, one may indeed be healed of that spurious love (pride & wrath) by experiencing the void behind the rent veil, a “healing” which would at least lead to a potentially saving despair and the eventual discovery of delight in the place of excitement. “Arise O Lord, & rend the Veil!” cries Los in lamentation: only imagination can expose the unprolific mystery of sexual fascination and worship, the anger and projection that constitute “that false / And Generating Love: a pretense of love to destroy Love” (J 17.25-26). Foucault would remind us, as well as Los, that the discourse of sexuality is a social fiction.

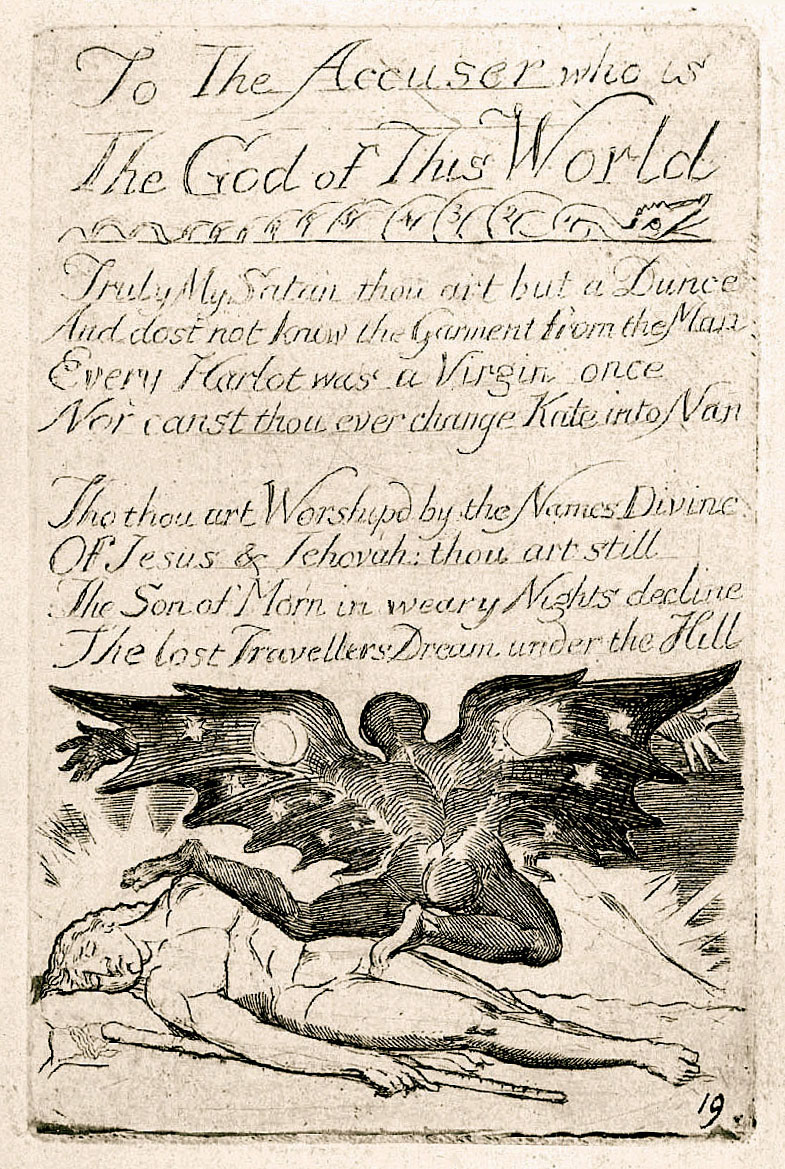

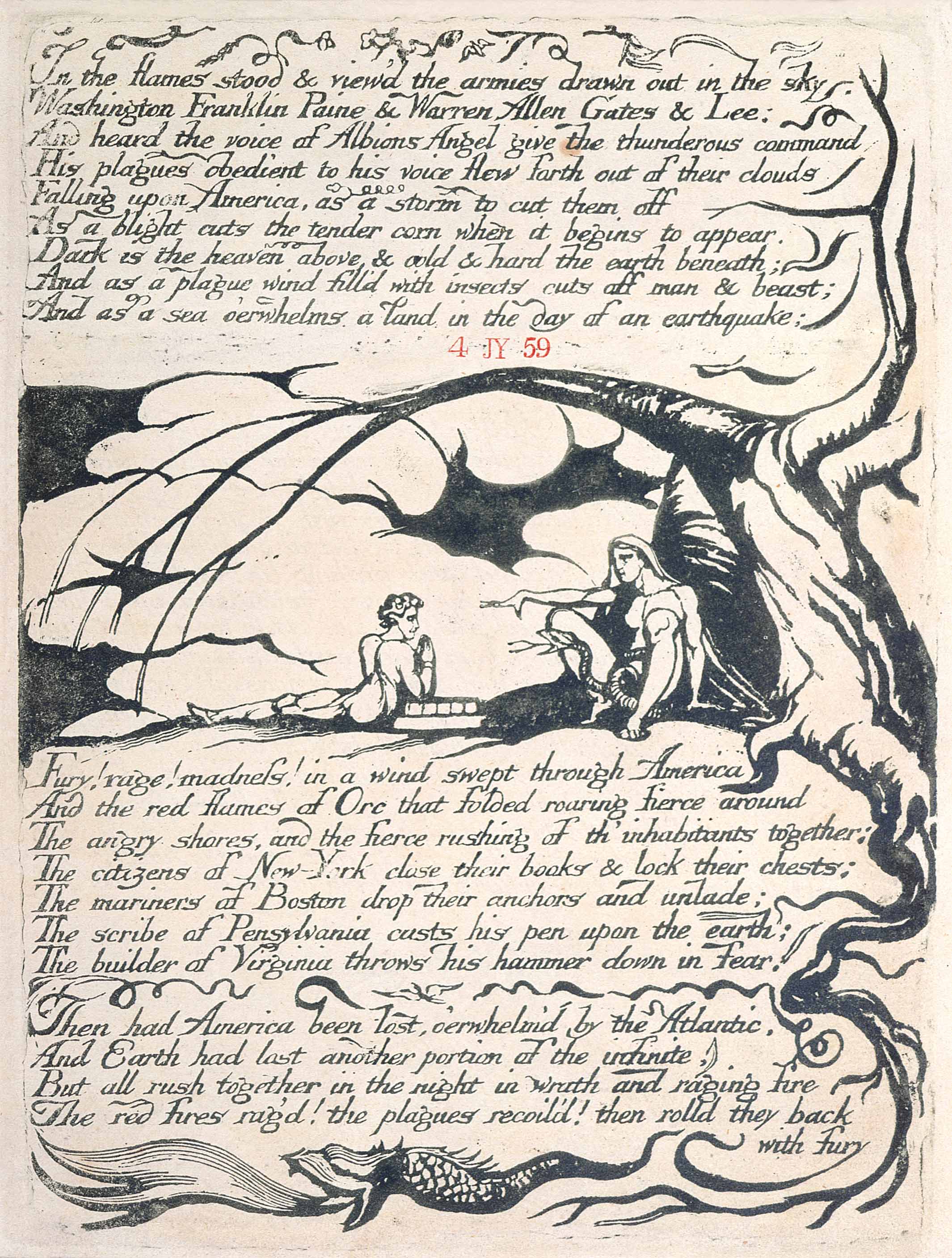

The creation of such a fiction may be seen in the “Epilogue” to For the Sexes: The Gates of Paradise (illus. 2). Here we see the Satanic spectre “that has resided in [the traveller’s] breast” now “rising out of the sleeping traveller.”16↤ 16 David V. Erdman, The Illuminated Blake (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1974), p. 279, and George Wingfield Digby, Symbol and Image in William Blake (Oxford: Clarendon, 1957), p. 53. Commentators seem to have avoided the obvious fact that the starry spectre’s foot is placed to double for the traveller’s snaky penis (compare illus. 3) rising in his sleep while the spectre in effect emerges from it. We have, then, a multistable image17↤ 17 See Aaron Sheon, “Multistable Perception in Romantic Caricatures,” Studies in Romanticism 16 (Summer 1977), 331-35; Stephen Leo Carr, “Visionary Syntax: Nontyrannical Coherence in Blake’s Visual Art,” The Eighteenth Century: Theory and Interpretation 22 (Autumn 1981), 222-48; and Fred Attneave, “Multistability in Perception,” Scientific American, December 1971, pp. 63-71; “multistability” offers another way of formulating “overdetermination.” —a graphic equivalent of the double- entendre—of the fallen lost traveller ready to copulate (“sleep”) with his own nocturnal emission (“emanation”—etymologically, a flowing-out”), his dream of the starry universe of generation: “The lost traveller’s dream under the hill.” This visualization of the sleeper’s condition is implicit in earlier references to Luvah’s “reasoning from the Loins in the unreal forms of Ulro’s night,” or that while “Albion slept,” his “Spectre from his Loins / Tore forth in all the pomp of War! / Satan his name” (J 27.37-39).

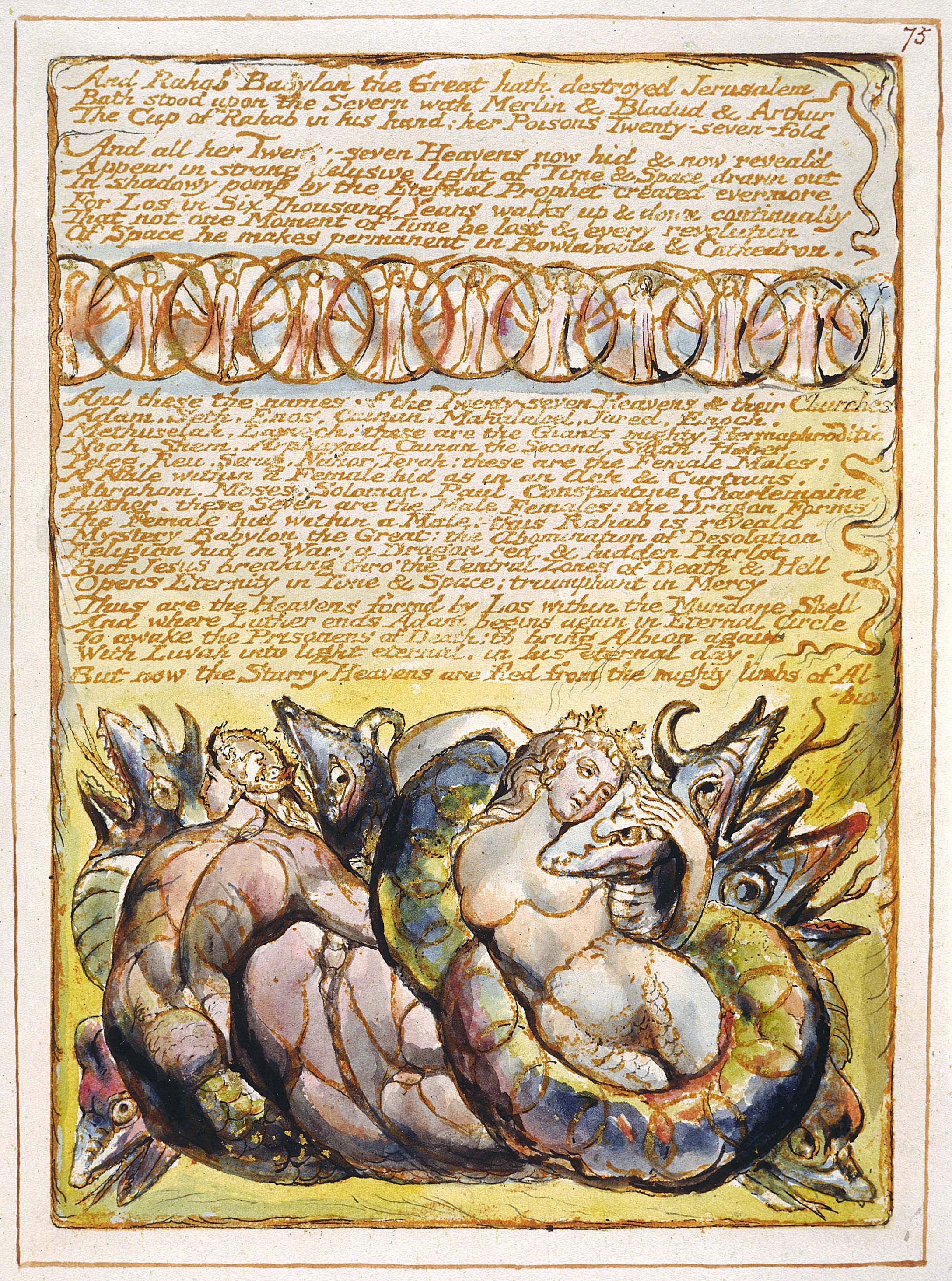

Plate 75 of Jerusalem offers a different conception in its multistable image (illus. 4). David Erdman suggests that we

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

The enveloping spectre of genital sexuality (identified by Blake in the famous letter of 23 October 1804 as “the enemy of conjugal love”) occasions the radical argument of the notebook poem, “My Spectre”:

Let us agree to give up LoveThe “infernal grove” is the site of genital and generative worship, where, as another poem suggests, we “suffer the Roman & Grecian Rods / To compell us to worship them as Gods” (E492).19↤ 19 Perhaps the arrestingly curious and repeated reference to “the detestable Gods of Priam” in Milton offers an oblique allusion to a (castrated?) Priapic pantheon: Priapus becomes polypus (Richard Payne Knight’s Discourse on the Worship of Priapus and its Connection with the Mystic Theology of the Ancients was published in 1786). Understanding the sexual reference of this and the other examples presented above, we realize also their limited transitory dimension in the global contest they serve to illuminate. Blake sees the potential of life, particularly of “All-bionic” intersubjective life, as exploited by the forces of generation (like the engendering genetic program) and driven to weave to dreams the sexual strife. These connotations are aspects of an old dream, whose unconscious status denotes that “Sexes must vanish & cease / To be, when Albion arises from his dread repose” (J 92.13-14).

And root up the infernal grove;

Then shall we return & see

The worlds of happy Eternity

(67-70)