minute particular

Iris & Morpheus: Investigating Visual Sources for Jerusalem 14

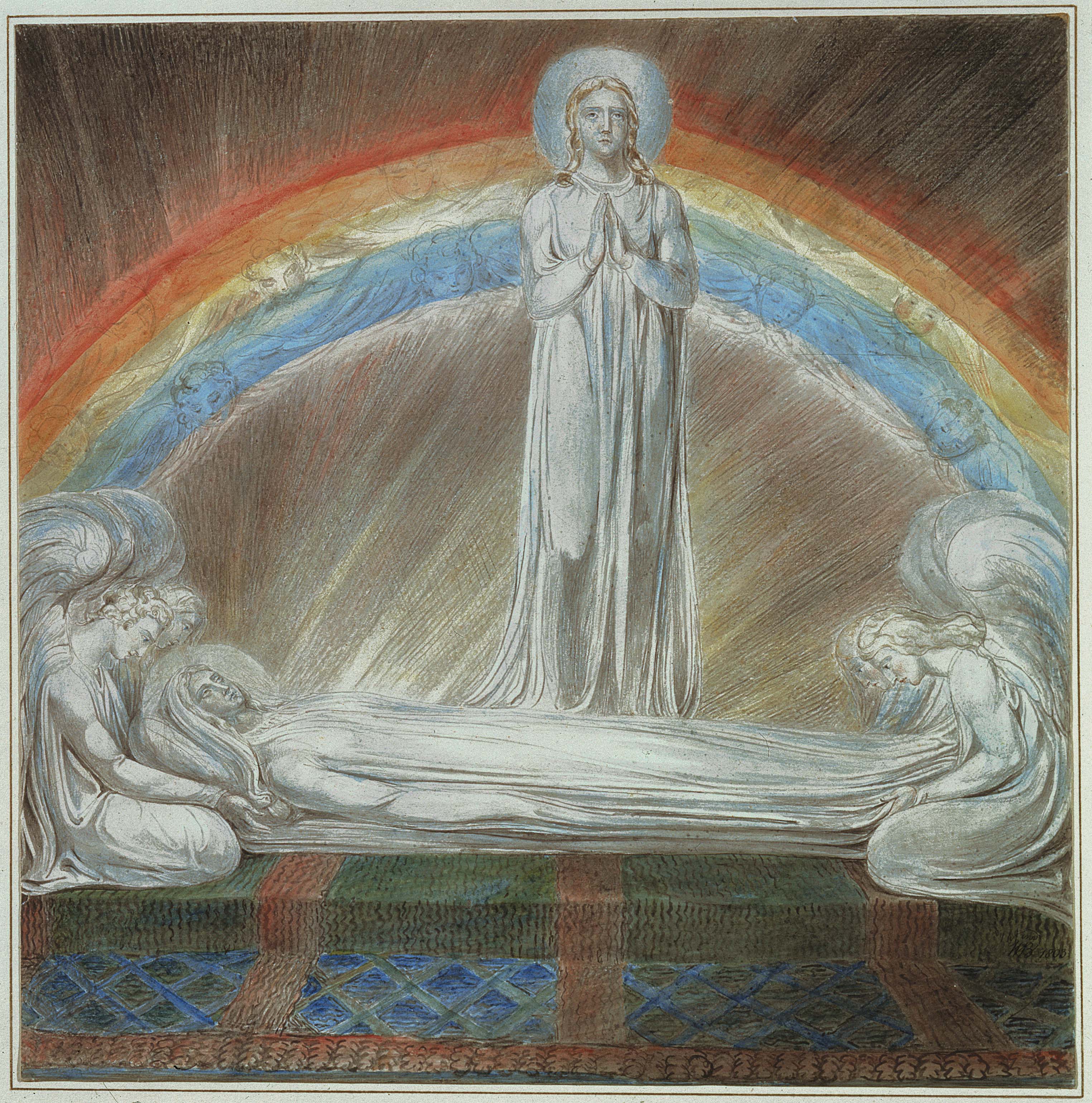

The design on plate 14 of Jerusalem (illus. 1) consists of a winged Jerusalem descending from a rainbow through a starry sky to awaken Albion from his deathlike sleep of mortality beside watery shores where he is attended by

two angels.1↤ 1 Some Blake scholars have identified the woman as Jerusalem: David V. Erdman, The Illuminated Blake (New York: Anchor Press/Doubleday, 1974), pp. 111, 293; Geoffrey Keynes, ed., Jerusalem (London: Trianon Press, 1974), pl. 14; Vivian de Sola Pinto, William Blake (New York: Schocken Books, 1965), p. 53; Jean H. Hagstrum, William Blake, Poet and Painter (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1964), p. 42; and Joseph Wicksteed, William Blake’s Jerusalem (London: Trianon Press, 1954), pp. 139-40, identifies her as “Jerusalem-Enitharmon/Fairy.” Those who identify her as someone else include S. Foster Damon, William Blake, His Philosophy and Symbols (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1924), p. 469, as Enitharmon; Edwin John Ellis and William Butler Yeats, The Work of William Blake: Poetic, Symbolic & Critical (London: Bernard Quaritch, 1893), vol. I, pp. 313-14, identify her as Leutha, daughter of Beulah “that follows sleepers in their dreams.” All further references to these authors are taken from the sources listed above unless otherwise indicated. The male figure is identified either as Albion (Wicksteed, de Sola Pinto, Erdman) or Los (Hagstrum, Damon, Keynes). Keynes identifies the last four lines on plate 14 as the passage from Jerusalem interpreted in Blake’s design. Although this design has been variously identified, the specific iconographic sources have not yet come to light. Attention paid to the particulars of the scene clearly shows that the illumination on plate 14 is, among other things, a parallel visual interpretation of the Greek myth of Iris and Morpheus.2↤ 2 Martin Butlin, in The Paintings and Drawings of William Blake (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981) illus. 795, identifies a sketch on a sheet from Hayley’s ballads (1802) as “Enitharmon shown as Iris with peacock wings, at the floor of plate 14”; Erdman offers an interpretation that is the most agreeable with the Iris myth, “a vision of the soul as the portion of man that wakes him from sleeping as body” (p. 111); Wicksteed and Ellis and Yeats state that the figure appears as if in a dream; de Sola Pinto calls her “Divine Womanhood” watching over his sleep; Damon interprets the design as inspiration visiting the poet in his sleep, but this is more likely an interpretation for Jerusalem 37 and 64.Iris was the Greek goddess who personified the rainbow on which she descended to earth as a messenger of the gods.3↤ 3 Hall, James, Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art (New York: Harper & Row, 1979), p. 162. Juno sent Iris to release the soul of Dido by rousing the sleeping Morpheus, the god of dreams.4↤ 4 Hall, p. 284. Morpheus was the brother of Thanatos (Death) and son of Hypnos (Sleep) and Nyx (Night). Nyx is usually represented with black wings outspread and holding an infant on each arm, one white (Sleep) and one dark (Death)—a possible thematic source for Jerusalem 4 and 33. The Kingdom of Hypnos was described by Ovid (Metamorphoses 11:589-632) as a cave in a hollow mountainside below which ran the River Lethe and next to which Blake shows Albion asleep. Lethe is the River of Forgetfulness, one of the five rivers surrounding Hades—an appropriate resting place for the god of dreams (and for Albion at this stage of Jerusalem).5↤ 5 Several scholars have commented on the watery shore in plate 14: Wicksteed calls it “a promontory surrounded by gentle water”; Keynes notes the “water’s edge”; and Erdman names it a “foaming ocean.” Iris is most often represented with her rainbow, as in this emblem from Boudard’s Iconologie of 1766 (illus. 2), or descending on bright wings from a rainbow to rouse the sleeping god.6↤ 6 Hall, p. 284. Blake’s engraving of a Cumberland design of Cupid and Psyche (in Irene Chayes, “The Presence of Cupid and Psyche,” Blake’s Visionary Forms Dramatic, ed. Erdman and Grant (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1970), illus. 14, 118) shows two butterflies resting on a hill that looks like a rainbow. Could this further connect Iris with the butterfly wings that Blake has given her? Perhaps the lines around Albion’s shoulder in plate 14 are meant to indicate wings at rest.7↤ 7 Another interpretation could be that Albion is shown as a body, without its soul, carried down to the banks of Lethe by Sleep and Death.

begin page 150 | ↑ back to topAlthough the various elements in plate 14 (rainbow, butterfly / woman, sleeping figure, water) clearly point to the myth of Iris and Morpheus, this parallel with the Greek theme alone does not account for the entire composition. The visual motif of reclining-male/hovering-female appears in several representations of physical-death/spiritual-rebirth throughout art. Ancient Egyptian funerary inscriptions (illus. 3) depict the Pharoah in his tomb attended by a hovering, female-headed, Ba bird—the soul separated from the physical body.8↤ 8 A. S. Roe, “The Thunder of Egypt,” William Blake: Essays for S. Foster Damon, ed. A.H. Rosenfeld (Providence: Brown University Press, 1969), p. 170. Bryant’s Mythology (1774) contains a section entitled “Of Egypt and Its Inhabitants . . . ” that was probably Blake’s early source for Egyptian symbols. The soul as female, hovering over the body as male, is a visual motif used repeatedly by Blake.

With his broad knowledge of art themes, Blake frequently drew from one artistic tradition while illustrating

In Gothic tomb sculpture, the Medieval gisant, usually shown reclining on his back, is sometimes depicted begin page 151 | ↑ back to top

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

Finally, the celestial bodies in plate 14 are worth noting.13↤ 13 Erdman identifies the planets on the upper right of plate 14 as Saturn, Venus, Mercury, Earth and the Moon. He presents an interesting theory: the six stars surrounding Jerusalem identify her as the true sun or seventh star. Several scholars have commented upon the portion of the sky within the arch of the rainbow: Erdman “Universe within” Albion (p. 293); Damon the State of Beulah; and Ellis and Yeats, Mundane Shell. The placement of the waxing moon is similar in the preliminary drawing, the finished plate design and

The artistic sources for plate 14 of Jerusalem demonstrate the diversity, richness and amazing clarity with which Blake chose his visual parallels.16↤ 16 As Mitchell says (p. 6) “the essential point is to note the wealth of implication which Blake can deposit in a design that has no ‘illustrative’ function . . . an independent symbolic statement.” In plate 14, he tied Jerusalem and Albion to compatible and expansive sources: the Egyptian Ba-Soul hovering over the material body; the Blessed Virgin in her role as intercessor for Christian souls; and, most obviously, the rainbow messenger, begin page 153 | ↑ back to top

Iris, in her descent to awaken Albion/Morpheus from his mortal dreams to spiritual life. The rays of the sun may be temporarily dimmed and the angels recoiled in momentary grief, but the design clearly heralds the positive outcome of Jerusalem.