article

begin page 96 | ↑ back to topBlake’s Job: Some Unrecorded Proofs and Their Inscriptions

Over the last several years, I have been attempting to record all pre-publication proofs of William Blake’s Job engravings. The resulting catalogue raisonné will soon be published (or perhaps by now has been published) by the William Blake Trust as a supplement to its long-awaited Job facsimiles. This catalogue includes a large number of previously unrecorded states, as well as several pre-publication sets of all 22 plates which have never been described. One such group of proofs merits individual notice in the journal of record for Blake scholarship because of the light it throws on Blake’s interpretation of the Book of Job. Further, two of the proofs bear inscribed aphorisms that deserve inclusion in the canon of Blake’s original writings.

On 9 December 1936, the American Art Association/Anderson Galleries Inc. of New York offered at auction as lot 62 a group of 21 pre-publication Job proofs. The catalogue includes a 4¼-page description of this collection. The vendor is not named and the extensive sales pitch says nothing about provenance. The title page of the catalogue names eight sellers, but none is known to have been a Blake collector. The auction included “other properties,” and thus the Job proofs may not have come from any of the eight. An annotated copy of the catalogue at the Rosenbach Museum & Library, Philadelphia, records a price of $5000 for lot 62,1↤ 1 I am grateful to Leslie A. Morris of the Rosenbach for this information. but I have not been able to discover the purchaser or present whereabouts of the proofs. They clearly are not the same as any of the 9 sets of complete proofs I have located, nor can any of the individual proofs outside these major sets be identified as dispersed remnants of the group sold in 1936.

The auction catalogue notes that all leaves in this proof set measure 11⅞ × 9 9/16 inches (30.2 × 24.3 cm.) and show a “single stab-hole.” Plates 17 and 20 are on laid paper and the remainder are on wove, with plates 3, 9, 12, 16, and 21 showing a “J. Whatman 1823” watermark.2↤ 2 The Riches set of proofs in the Fitzwilliam Museum, the White-Rosenwald set in the National Gallery of Art, Washington, and some of the proofs in the Linnell-Rosenwald group (National Gallery of Art) are on laid papers of at least two varieties. One example from the last group, plus five impressions in the set of proofs owned by Philip Hofer, show the Whatman 1823 watermark. The title page, printed on laid India paper, is the only plate not in a pre-publication proof state. It probably was not printed with the other plates and may have been added at a later date to complete the set. The plate by plate descriptions in the sale catalogue range from helpful comparisons between the proofs and finished states to vague generalities (e.g., on plate 8 “the general treatment of the finished work is more finished and pronounced”). These descriptions do not permit the precise determination of each print’s position in the sequence of known proof states, but it would seem as though many, perhaps all, of these impressions represent the first states after the addition of border designs. All are described as lacking imprints and the “Proof” inscription. If indeed these are first pulls after the addition of borders, they record a crucial point in Blake’s development of the Job copperplates, perhaps the first time he could determine fully the success or failure of his combination of outline borders and highly-finished central designs. The rediscovery of these impressions could occasion some major adjustments in the known record of progress proofs.3↤ 3 The sale catalogue descriptions are not sufficient to permit the inclusion of the untraced proofs in the Blake Trust catalogue of states. It will, however, contain a separate list of excerpts from the 1936 auction catalogue and speculations about the state of each untraced proof.

Among the more intriguing features of these proofs—or, to be more exact, of the 1936 catalogue descriptions—is the absence of a few biblical inscriptions which appear on all previously recorded and traced impressions. Plate 5 is said to lack “And it grieved him at his heart / Who maketh his Angels Spirits & his Ministers a Flaming Fire.” These words appear as the second and third lines of text beneath the central design on the earliest traced state of plate 5 with the border design (Riches set, Fitzwilliam Museum, and Linnell-Rosenwald set, National Gallery of Art, Washington) and in all subsequent states. Plate 16 is described as lacking “The Accuser of our Brethren is Cast down / which accused them before our God day & night.” The first of these lines, but not the second, is present just left of the central design in the previously recorded first proof state with the borders (Linnell-Rosenwald set). The next state (Riches, Linnell-Rosenwald, and White-Rosenwald) also lacks the second line, but it appears in all later states. The 1936 auction catalogue also notes a variant in the second line of text beneath the design on plate 16: “Even the Devils are Subject to Us thro thy Name. And he said unto them, I saw Satan as lightning fall from Heaven.” These words from Luke 10: 17-18 are emended in the next proof state so that the beginning begin page 97 | ↑ back to top of the second sentence reads “Jesus said unto them, . . . ” Blake very probably made the change simply to identify the speaker.

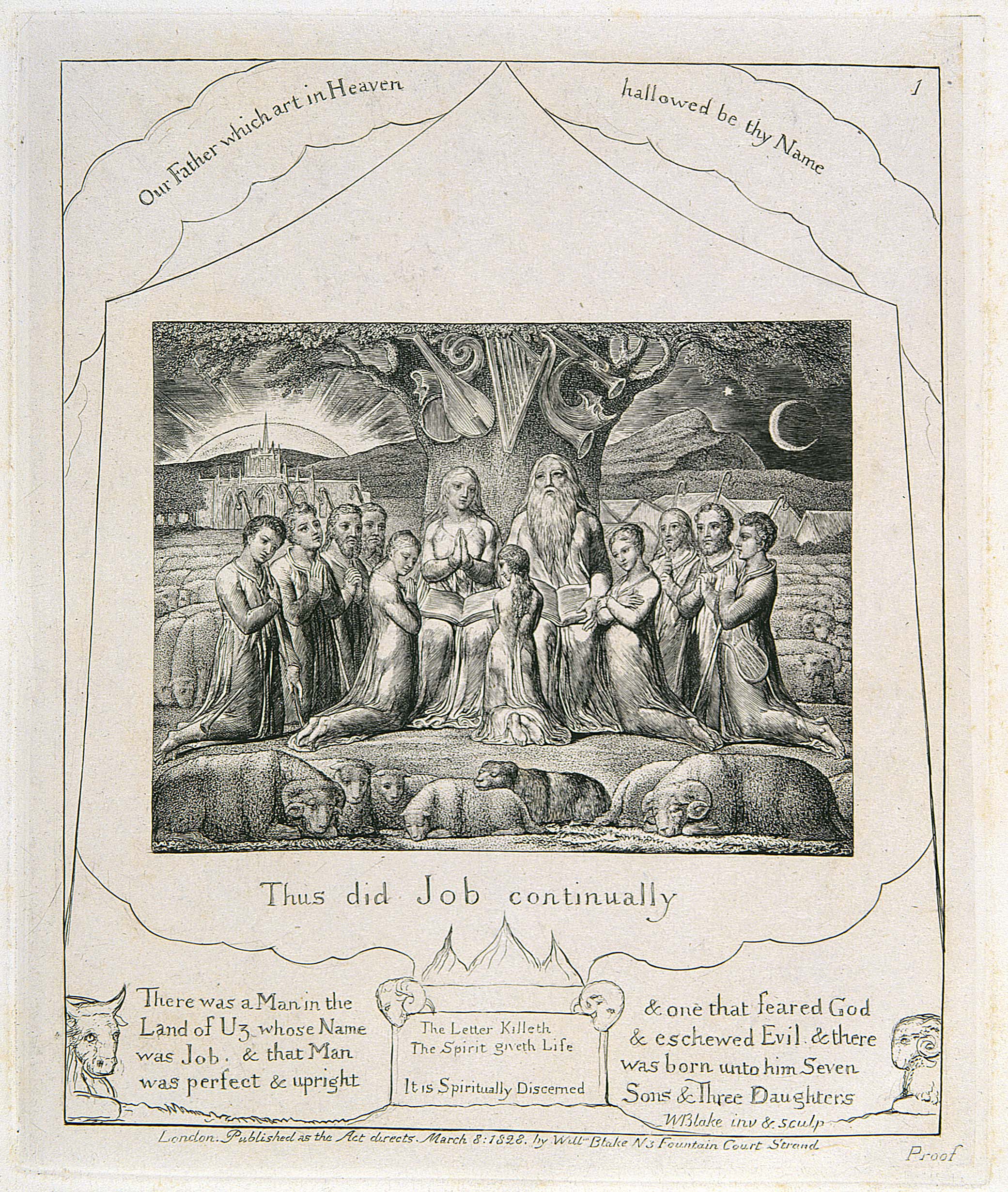

By far the most significant variants, textual or pictorial, noted in the 1936 catalogue appear on plates 1 and 21. Fortunately, both are reproduced. The illustrations accompanying this essay were made from photographs

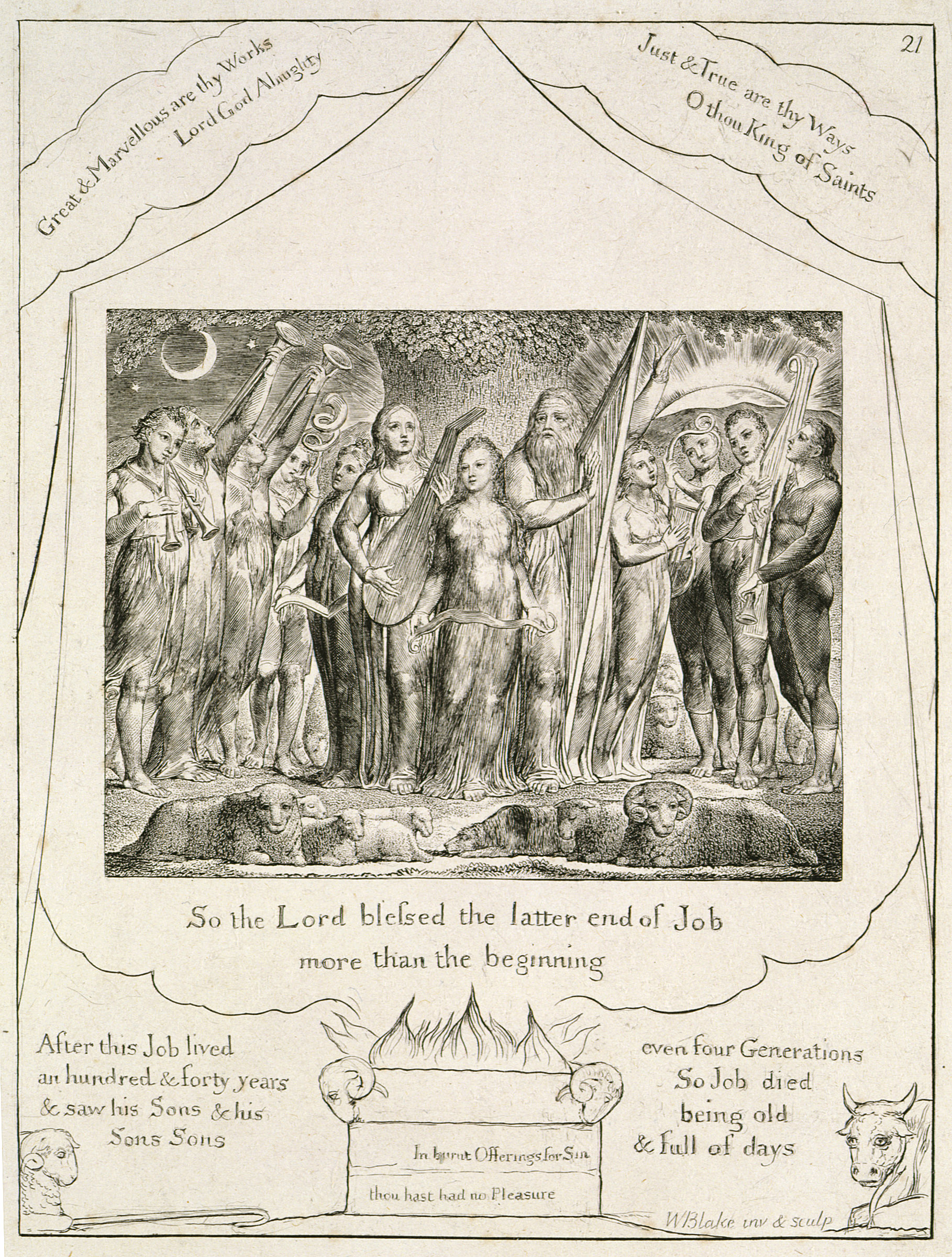

The inscriptions beneath the altars are unique to the untraced proofs. In the next known state of plate 1 (Essick collection [illus. 3] and Linnell, White, and Riches proof sets), the ground has been completely cleared of all letters and “The Letter Killeth / The Spirit giveth Life” added to the upper part of the altar. Ground and altar remain unchanged in all later states. The next begin page 99 | ↑ back to top recorded state of plate 21 (White [illus. 4] and Riches proofs) shows that the ground has been cleared, additional tongues of flame have been added above the altar, and the lettering on the altar has been recut more clearly. These features remain unaltered in subsequent states.

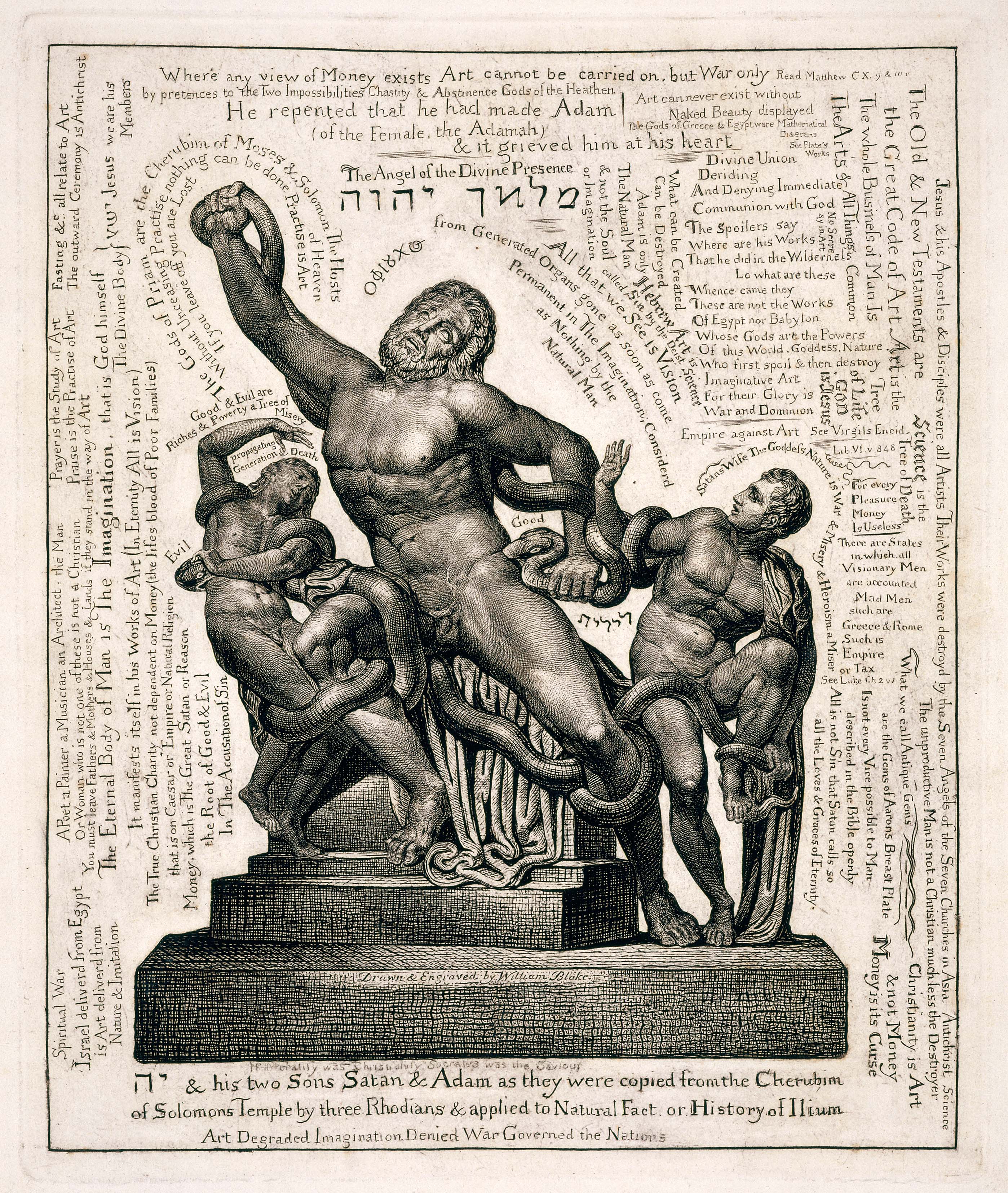

The proof inscriptions in question are the only

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

The marginal inscriptions throughout Job influence the “reading” of the central designs. The position of the unique lines on the untraced proofs of plates 1 and 21 recommends them as the grounds for interpretations of all that is pictured and written above. “Praise to God is the Exercise of Imaginative Art” contrasts with the

Charles Eliot Norton was the first to suggest that Blake pictures Job in a fallen state of consciousness at the beginning of the series. As Norton wrote in 1875, “Job’s prayers and burnt-offerings, in the days of his prosperity, were, after all, but the propitiatory and selfish sacrifices of the law.”8↤ 8 William Blake’s Illustrations of the Book of Job (Boston: James R. Osgood, 1875), unnumbered page of comments on “Plate I.” Subsequent criticism has followed this crucial conception of Blake’s vision of Job, one that places the first and last plates in opposition and thereby influences the shape of the entire visual narrative. This perspective is placed into doubt by the proof inscription which, when combined with the inscription (“It is Spiritually Discerned”) on the altar immediately above, suggests that the books held by Job and his wife and the prayerful attitudes of the whole family represent a “Study of Imaginative Art” capable of achieving spiritual insight. The proof inscriptions together thwart the usual juxtaposition of the first and last plates and suggest instead underlying similarities between passive prayer and active praise. The latter may be superior to the former, but the difference is in means, not ends.

Before thoroughly revising our sense of the Job engravings on the basis of the proof inscriptions, we must consider several important details in the development of the first design. Its proof inscription certainly disrupts the conventional interpretation of the central design for the proof state on which it appears, and perhaps for all earlier versions including the water color executed for Thomas Butts c. 1805-1806, but the elimination of the line may also signal a shift in Blake’s own conception of the Job series. The removal of the sentence from the ground in the next recorded proof state is accompanied by the addition of “The Letter Killeth / The Spirit giveth Life” on the altar above (see illus. 3). These words prompt a very different view of the books and family activities in the central design. The text lower on the altar from 1 Corinthians 2:14 tends to confirm the truth and importance of the new lines from 2 Corinthians 3:6 opposing letter and spirit. Norton, in his commentary noted above, begins by quoting these lines; later critics also stress their importance in establishing the donnée for the whole series.9↤ 9 See for example Wicksteed (1924), p. 90: “The written books, and the silent instruments above, represent the letter and the spirit, referred to on the altar below, and here we see Job dwelling on the letter that ‘killeth,’ while the Spirit that ‘giveth life’ is not yet waked.”

In his writings on the arts, Blake stresses the unity of conception and execution. The textual revisions on the first Job engraving would seem to demonstrate the practical relevance of this ideal to Blake’s habits as a visual/verbal artist. In light of the considerable change in interpretation warranted by this two-fold revision, we cannot assume that Blake’s full conception of the meaning of the design preceded its execution in copper. Only as he slowly developed his images in the difficult medium of line engraving did Blake come to realize that the “perfect and upright” man of “the land of Uz” (Job 1:1) was not an archetype of the prayerful student of the arts but one who had already fallen in thrall to the dead letter of the law. The thematic shape of the entire series, particularly the errors which adumbrate Satan’s entry into Job’s life and the oppositions between letter and spirit visualized by the first and last scenes, came into being at a late stage in Blake’s long history as an interpreter of the Book of Job.