article

begin page 84 | ↑ back to top

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

Europe 6: Plundering the Treasury

In The Illuminated Blake, David V. Erdman suggests that plate 6 of Europe: A Prophecy (illus. 1) presents a case of incipient cannibalism, citing as evidence the gloss supplied by Blake’s friend George Cumberland which labels the picture “Famine” and includes the notation, “Preparing to dress the Child,” along with a quotation from Dryden: “ . . . to prolong our breath We greedily devour our certain Death.”*↤ I wish to thank the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts, at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, for the award of a Visiting Senior Fellowship during the Fall of 1986, of which this essay is one result. Erdman observes that the picture demonstrates not only that the camp followers of War are Famine, Pestilence, and Fire, but also that “it is the rich and powerful who devour the children, the young who die of plague, women and children who perish in flames.”1↤ 1 The Illuminated Blake, annot. by David V. Erdman (Garden City, NY: Anchor/Doubleday, 1974) 164. Plate numbers in this discussion follow Erdman’s. Already in 1784 Blake had assembled these apocalyptic elements in his Royal Academy picture of War unchained by an Angel, Fire, Pestilence, and Famine following; by 1794 he had begun a related series of pictures that would culminate in the watercolors of Pestilence, Fire, War, and Famine—the latter, explicitly representing cannibalism—which he completed for Thomas Butts c. 1805.2↤ 2 See Martin Butlin, The Paintings and Drawings of William Blake (2 vols.; New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 1981), 1: pl. 221, 187-96. That Blake had already begun to associate cannibalism with famine by the time of Europe 6, however, is apparent from the relationship of Blake’s design to several images from the popular and widely-circulated work of James Gillray.

That Blake was familiar with Gillray’s work is evident from numerous connections between Gillray’s political prints and Blake’s visual works from the early 1790s.3↤ 3 Erdman’s suggestion, for instance, that Blake’s emblem “I want! I want!” (from For Children, 1793) is directly indebted for the detail of the ladder extending toward a crested moon to Gillray’s Slough of Despond of 2 January 1793 provides what would seem to be indisputable evidence of the connection. See The Notebook of William Blake, ed. David V. Erdman, rev. ed. (New York: Readex, 1977), [N40], as well as Erdman, Blake: Prophet against Empire, rev. ed. (Garden City, NY: Anchor/Doubleday, 1969), passim. On Blake’s use of other visual material from political cartoons, see also Nancy Bogen, “Blake’s Debt to Gillray,” AN&Q 6 (1967): 35-38, and Stephen C. Behrendt, “ ‘This Accursed Family’: Blake’s America and the American Revolution,” The Eighteenth Century: Theory and Interpretation 27 (1986): 26-51. Only a year Blake’s senior, Gillray had entered the Royal Academy in 1778, the year before Blake, and had become an acquaintance and correspondent of Fuseli in the following years. Asserting flatly that Blake “must have been acquainted with Gillray,” David Bindman observes that despite their later political differences the two artists “share a sense of the unremitting corruption of the world.”4↤ 4 David Bindman, William Blake: His Art and Times (New Haven: Yale Center for British Art, 1982) 25. Precisely this sense of unremitting corruption links Europe 6 with Gillray’s work. Significantly, though, the background rather than the figures themselves establishes the tie.

The dark, arching stonework of the hearth in Blake’s picture is unmistakably that of the Treasury, which appears frequently in Gillray’s prints, occasionally bearing not the usual inscription, “Treasury” (which appears in prints of 21 April 1786, 29 May 1787, 14 August 1788, 3 June 1793, 24 February 1801, and 1 May 1804), but another such as “Excise-Office” (9 April 1790, where “Treasury” has been crossed out and the new words are being inscribed) or “Granary” (19 January 1803). The most immediately relevant occurrence (and one of the earliest) of the Treasury facade is in Monstrous Craws, at a New Coalition Feast (illus. 2), published 29 May 1787 and extant as both monochrome etching and hand-colored aquatint. The print takes as its point of departure the recent exhibition in London of two women and a man whose remarkable greatly distended necks had undoubtedly resulted from goiter affliction.5↤ 5 Richard Godfrey, English Caricature, 1620 to the Present (London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1984) 81-82. Gillray appropriated this sensational topical image for his picture of Queen Charlotte, the Prince of Wales, and George III (whom Gillray dressed as a woman, to replicate the sexes of the unfortunate trio exhibited in London) devouring golden porridge from a great bowl bearing the inscription “John Bull’s Blood”—the national wealth—in a variation of one of Gillray’s favorite themes: the exorbitant public expense of maintaining the royal family. The Prince of Wales, his own nearly empty craw symbolic of his perennial want of ready money, glances enviously at his greedy mother. In his left hand he holds a spoon inscribed “£10000 pr An.” and in his right another inscribed “£60000 pr An.,” these being the sums allotted him by Parliament and the king.

Visible within the arch in Monstrous Craws and most of the other prints in which the Treasury appears are its spike-topped gates: here the spikes surmount a horizontal line that passes behind the king’s right hand. The distinctive wall, rounded arch, and gate spikes all recur in Europe 6, the horizontal line (in nearly the same position where Gillray locates it) split to flank the hearth-grate, the spikes modified to wavy verticals at the kettle’s right and crosshatched lines at its left. Even the wavy lines indicating the wall’s texture recur in Europe 6, as they do in other plates in Europe and America.

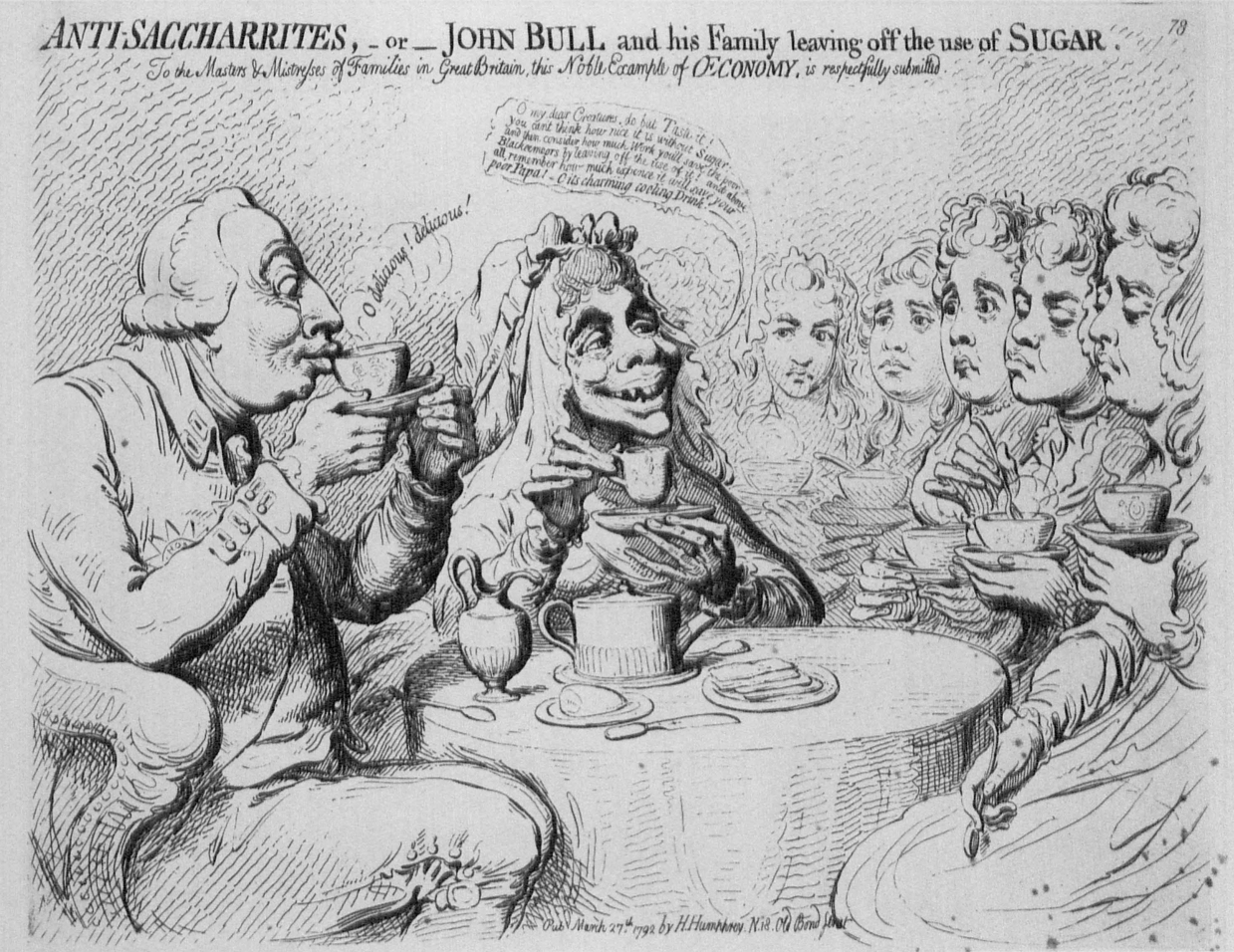

Gillray often ironically juxtaposed the notorious public extravagance of the royal children—particularly the Prince of Wales, whose debts were both a public scandal and a public burden—with the purportedly modest private lifestyle of the king and queen, as in his famous print of royal belt-tightening, Anti-Saccharites, or John Bull and his Family leaving off the use of Sugar (published 27 March 1792; illus. 3). Since the extreme frugality of the king and queen in private life was well known, considerable discussion (and much political satire) centered upon the question of what became of the large sums for which the king, citing his considerable begin page 86 | ↑ back to top

Blake’s fusion of the familiar images of barred hearth and Treasury facade produces in Europe 6 a harrowing image that goes well beyond the scope of Gillray’s prints and imbues the caricaturist’s elaborate play upon the act of eating, in Monstrous Craws and elsewhere, with distinctively cannibalistic overtones. As in America, what is cannibalized is the very basis of society, the family: humanity consumes itself. There are no men, for instance, in Europe 6, for they are presumably begin page 87 | ↑ back to top

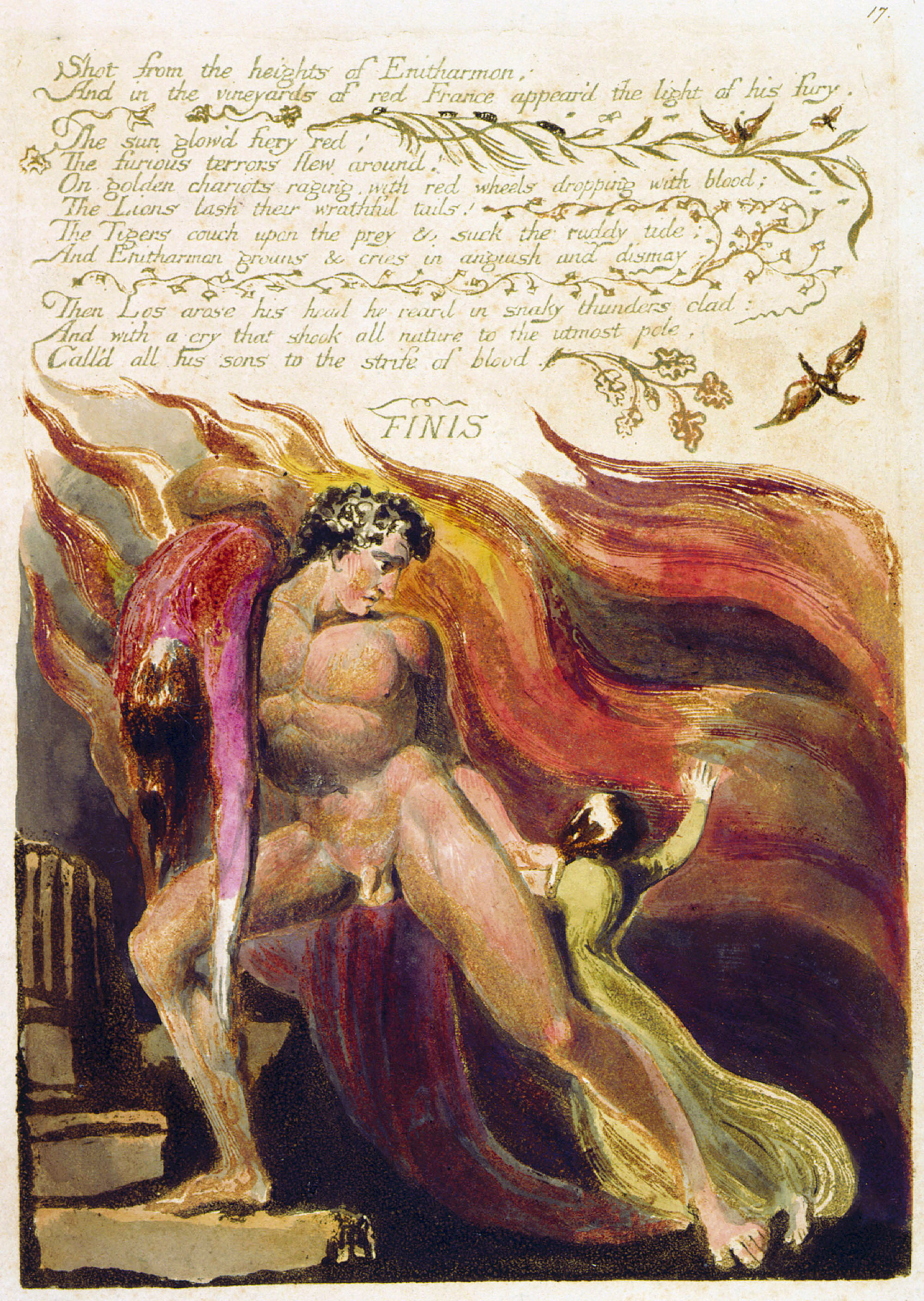

As in America, in which the family unit is consistently depicted as shattered by death or enforced separation, in Europe the only “whole” family occurs in the large illumination to the final plate (illus. 6), where a man carries an apparently unconscious woman while compelling a female child to climb the stair with him. Blake’s arresting image derives almost certainly from begin page 88 | ↑ back to top

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

That the family in Europe 15 is ascending the stairs past a broken classical column is a relatively positive sign, a visual hint of liberation from the dungeon of Europe 13 and an indication of at least potential post-millenial survival. Given the apparent escape, intact, of this family unit, humanity seems yet to stand a chance of avoiding total self-immolation. On the other hand, considering the bloody turn the Terror-ridden French Revolution had taken by the time Blake completed Europe, these ominous, ambiguous flames may be those not of liberation and purification but of blind self-consumption, a possibility underscored by another particularly grisly Gillray print.

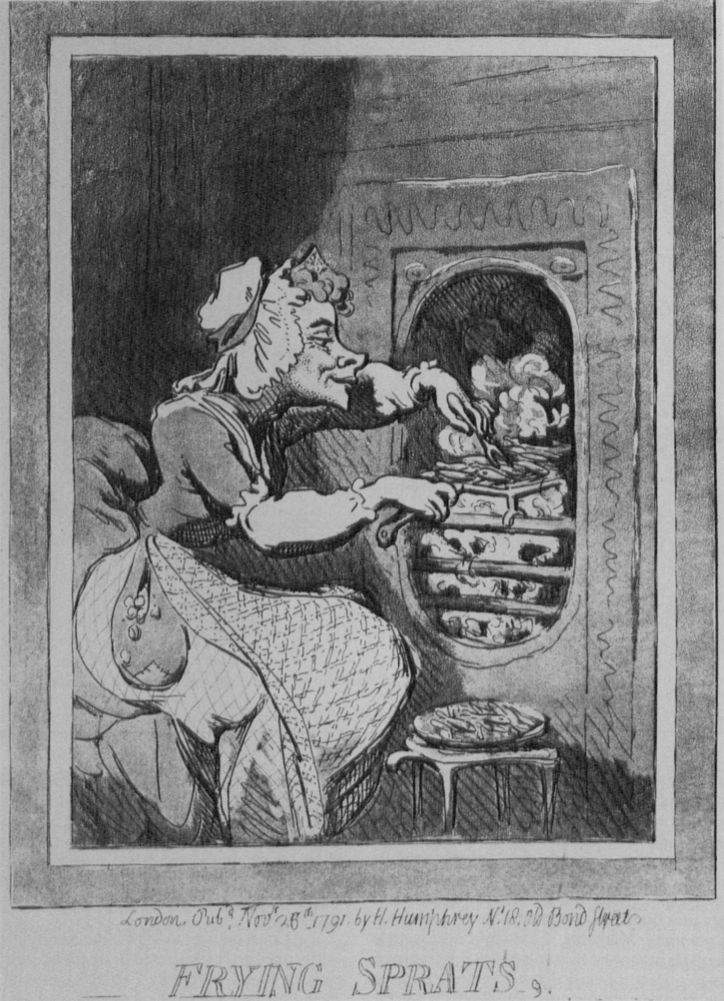

Un petit Souper, a la Parisienne; or, A Family of Sans-Culotts refreshing, after the fatigues of the day (illus. 8), published 20 September 1792, makes concrete and explicit the ravenous cannibalism of the Revolutionary France of the September massacres. Here a skewered child hangs before another of those horizontally-barred fire-grates, “dressed” for cooking and basted by a pistol-packing hag while other citoyens feast on a variety of body parts, including a heart. On the table in gruesome parody of the familiar subject of St. John the Baptist is a severed head on a platter, its right eye and ear hungrily devoured by a scrawny Frenchman. Interestingly, at the lower right another man sits on the naked torso of

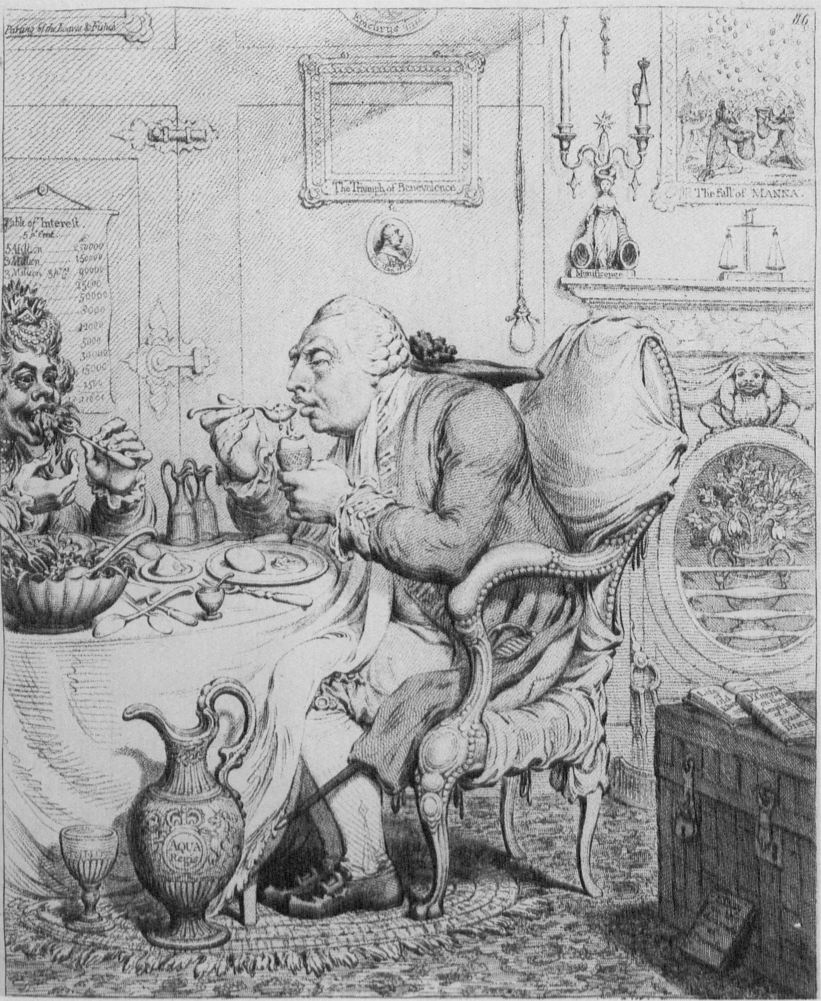

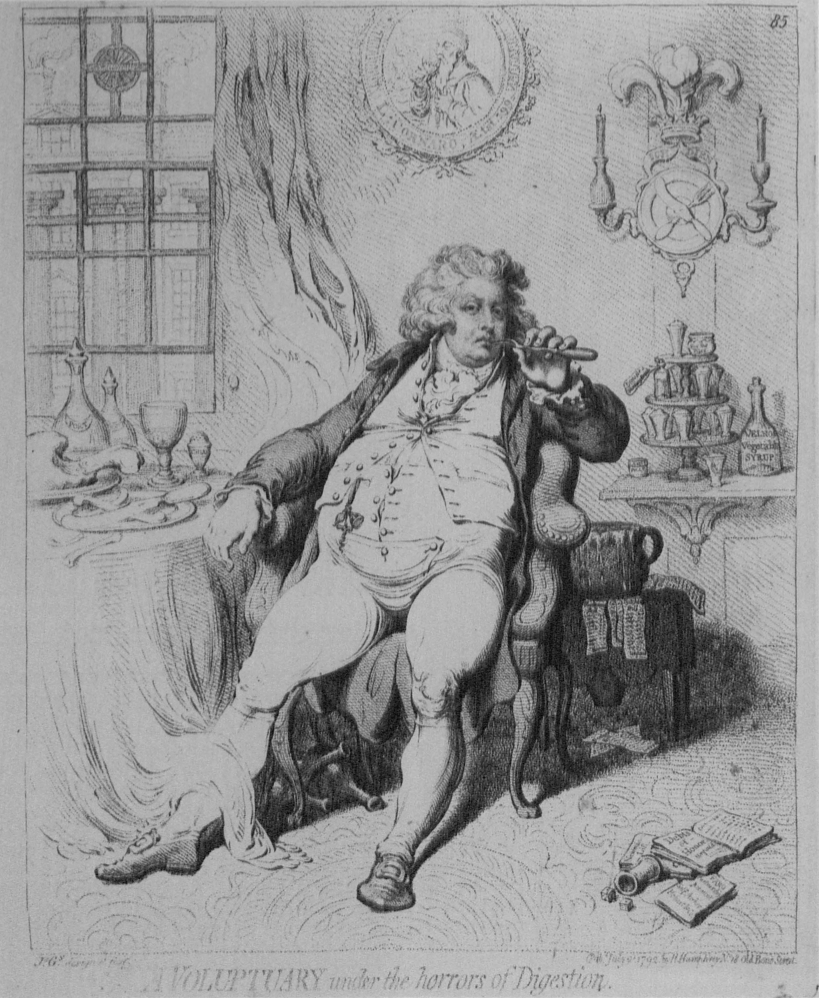

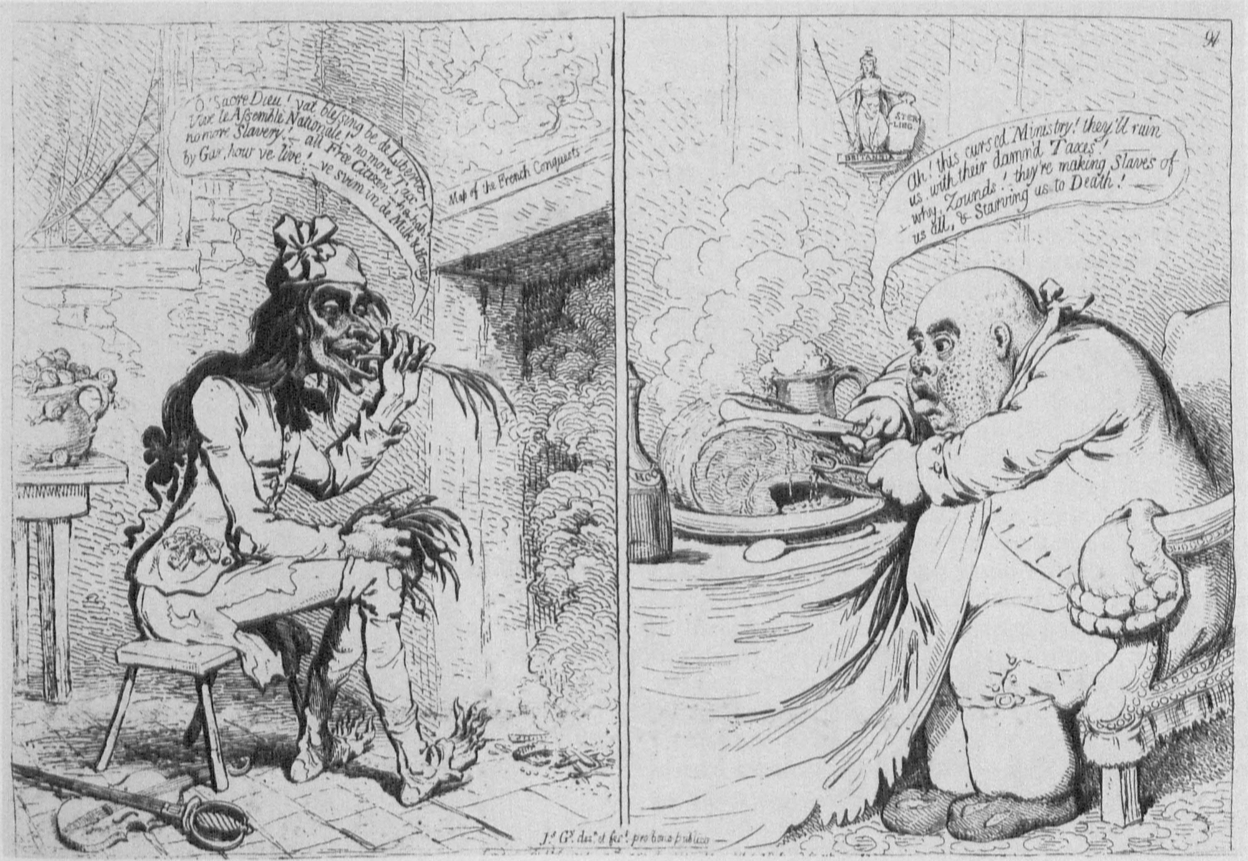

begin page 91 | ↑ back to topA final word about Gillray’s many variations on the topos of eating is appropriate in conclusion. The act of consuming provided a singularly pertinent metaphor for the self-destructive state of affairs in England (and on the Continent) as caricatured by Gillray and his contemporaries.12↤ 12 See also Ronald Paulson, Representations of Revolution (1789-1820) (New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 1983) 200. Popular art furnished abundant precedents for the sort of references to actual and metaphorical cannibalism we encounter both in Blake’s visual art (e.g., the Famine of c. 1805, the background of which still echoes the Treasury facade) and in his illuminated poetry (e.g., Jerusalem, plates 25, 69, and 85). Gillray’s well-known A Voluptuary under the Horrors of Digestion (2 July 1792; illus. 9), which immediately preceded Temperance enjoying a Frugal Meal and epitomized profligacy and gluttony, furnishes a stark contrast to the emaciated figures either depicted or described in America and Europe and represented in visual works like Pestilence, Famine, and War (A Breach in the City, the Morning after the Battle), all of which were evolving in the 1790s. Furthermore, the sharply anti-gallican double print of 21 December 1792, French Liberty [and] British Slavery (illus. 10) ironically contrasts the relative luxury and security of the fat Englishman (a John Bull type), who laments his high taxes while carving for himself begin page 92 | ↑ back to top

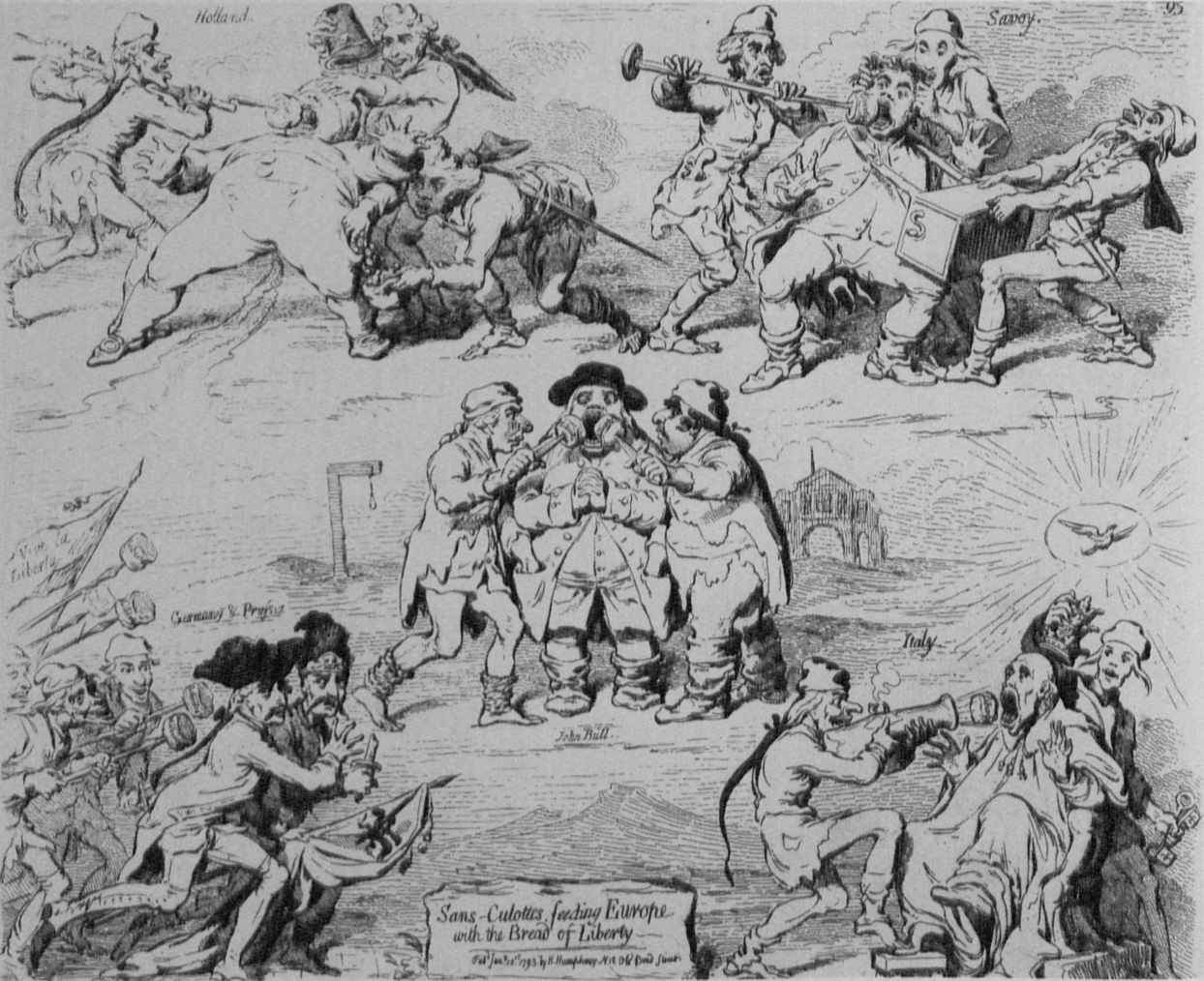

Taken with the elaborate force-feeding depicted in Sans-Culottes feeding Europe with the Bread of Liberty (12 January 1793; illus. 11), this double print, along with a whole series of prints from 1787-1795, underscores the contemporary political cartoonist’s preoccupation with the metaphor of eating. It was, then, entirely natural for Blake both to embed intimations of cannibalism within the familiar visual metaphor of Europe 6 and to capitalize upon the rich texture of association invoked by the looming presence therein of the familiar Treasury facade, and he could have trusted his contemporaries to recognize and to credit the topical political significance of his reference.