article

begin page 127 | ↑ back to topThe Chamber of Prophecy: Blake’s “A Vision” (Butlin #756) Interpreted

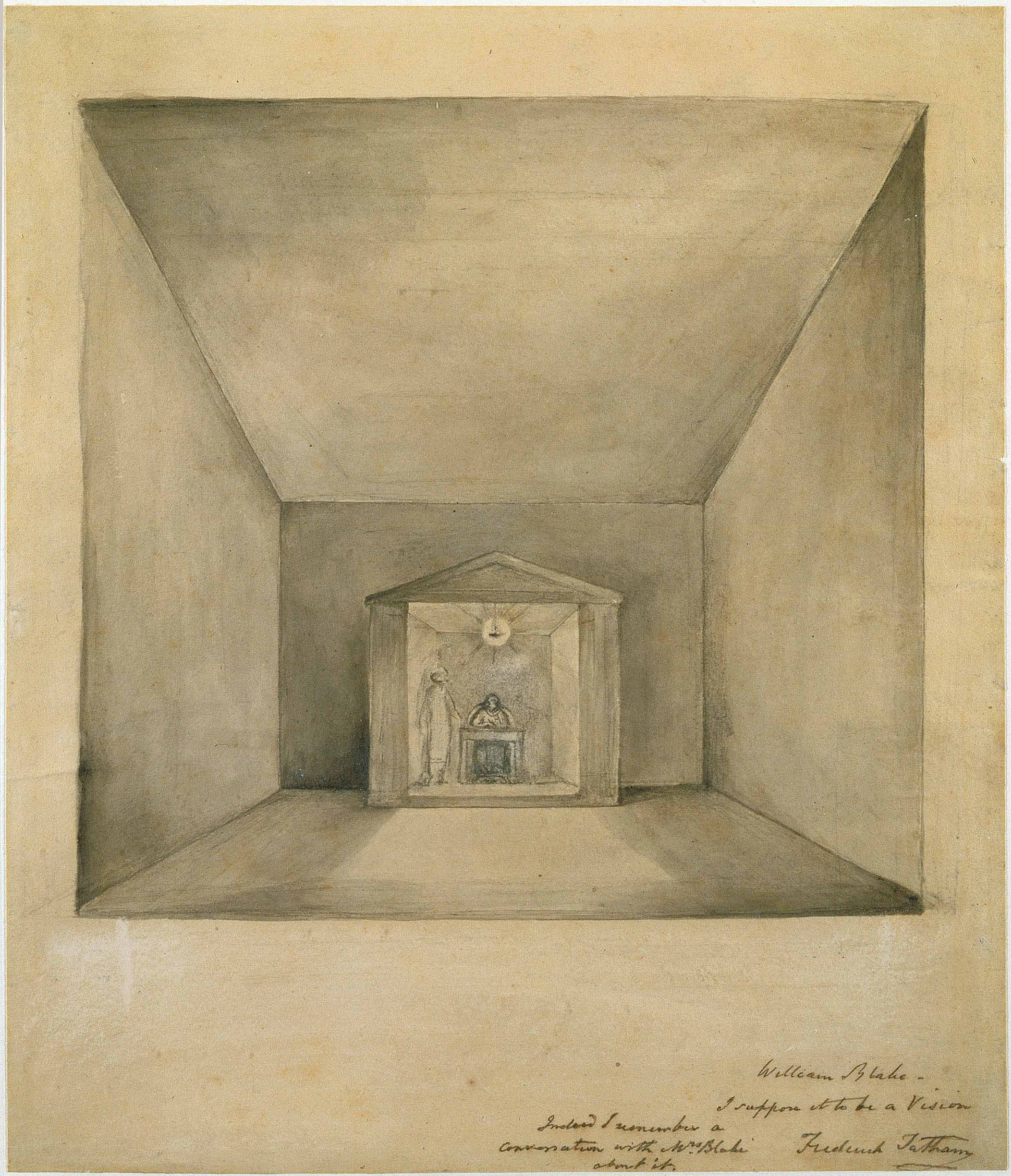

Frederick Tatham has long been regarded as an unreliable witness to Blake’s intentions, but his comments on the drawings that passed through his hands are difficult to ignore simply because they often represent the only information that we possess. Thus his inscriptions on the drawing known as A Vision: The Inspiration of the Poet1↤ 1 Martin Butlin, The Paintings and Drawings of William Blake, 2 vols. (New Haven: Yale UP, 1981) #756. The information found there must now be supplemented with that in Martin Butlin, William Blake 1757-1827 (London: The Tate Gallery, 1990) 251. The Tate Gallery’s purchase of the drawing was recorded in a note by Robyn Hamlyn in Blake 23 (1990): 213. (illus. 1) have been taken as appropriate guides to its subject, and what little commentary there has been has focused on the odd spatial sense carried by the perspective of the drawing rather than on its subject.2↤ 2 See Robert Rosenblum, Transformations in Late Eighteenth Century Art (Princeton: Princeton UP, 1969) 189-91.

But Tatham’s inscriptions need fuller consideration in the light of his known unreliability. In the case of this drawing they read “William Blake./ I suppose it to be a Vision/ Frederick Tatham” and “Indeed I remember a/ conversation with Mrs. Blake/ about it.” I have taken the texts from Butlin’s Tate Gallery catalogue, since this gives a useful indication of the fact, evident in the photograph, and noted by Butlin, that the two inscriptions are indeed separate. The note about the conversation with Mrs. Blake was obviously written in later as an afterthought, being placed under and to the side of the original inscription, which records simply the vaguest of guesses at the subject. The conversation may indeed have taken place, but it clearly did not help a great deal. We are pretty much on our own if we want to make an effort to understand the drawing.

The drawing is associated by Butlin with the Visionary Heads drawn by Blake for, and it seems usually in the presence of, John Varley.3↤ 3 Butlin places the drawing among the Visionary Heads in The Paintings and Drawings of William Blake, but is somewhat more cautious in his recent Tate Gallery catalogue, where he writes: “Although different in character from the other Visionary Heads this drawing probably dates from about the same time.” The size of the paper used for the drawing (24.3 × 21 cm.) makes it impossible that it could have come from the now dismembered small sketchbook, which consisted of sheets of approximately 20.5 × 15.5 cm. There were also a good many drawings done on separate sheets of various sizes, and the present drawing could conceivably be one of them. As if to counter that possibility, however, Geoffrey Keynes notes that “most of the drawings remained in the collections of Varley and Linnell.”4↤ 4 Geoffrey Keynes, Blake Studies, 2nd ed. (Oxford: Oxford UP, 1971) 130. Butlin’s catalogue confirms that statement by showing that in virtually every case the Visionary Heads either have a note by Varley, or come from the collections of Varley or Linnell; many demonstrate both forms of connection. The only exceptions noted by Butlin, other than the drawing under consideration here, are Visionary Head of a Bearded Man, Perhaps Christ (#758), which has a note by Tatham reading “one of the Heads Wm. Blake saw in Vision & drew this. attested Fredk. Tatham,” and A Visionary Head (#759r), which has a note by Tatham that reads “one of the heads of Personages Blake used to call up & see & sketch. supposed rapidly drawn from his Vision. Frederick Tatham.” Both of these came through the collections of Mrs. Blake and Tatham. In addition, there is the dubious case of #764, untraced since 1862, which Butlin suggests may in fact be identical with either #766 or #765, the former untraced since 1876, and the latter bearing an inscription that is probably by Varley. It seems that on the very rare occasions when Tatham got hold of one of the Visionary Heads, he was anxious to advertise the fact, doubtless in the belief that this begin page 128 | ↑ back to top would raise the value of the drawing. His identification of the drawing discussed here with the simple statement “I suppose it to be a Vision” is a good deal less confident and specific than the notes added to the two drawings described above, and could well be read as implying considerable doubt on his part as to whether the drawing was in fact associated with the Varley series. In addition to the unusual vagueness of Tatham’s note, the drawing comes from the collections of Mrs. Blake, and then Tatham, and these contain very few of the Visionary Heads.

The situation has now been complicated a little by the rediscovery of the larger Blake-Varley sketchbook, with leaves of 25.4 × 20.3 cm., bearing signs that several leaves were removed early in its history.5↤ 5 I take my information on this sketchbook from Robert N. Essick, “Blake in the Marketplace, 1989, Including a Report on the Recently Discovered Blake-Varley Sketchbook” Blake 24 (1990): 221-24. This is closer to the size of the present drawing, but several facts make it unlikely that the drawing comes from this sketchbook. One is that the paper size, though close, does not quite match: our drawing seems just a little too wide (21 cm.) to fit. Another is the evidence of the watermarks; Essick records that some of the leaves of the sketchbook bear an 1804 mark, while Butlin records that the drawing is on undated paper marked “RUSE & TURNERS,” and gives evidence from G. E. Bentley, Jr., that paper made by that company bore dates of 1810, 1812, and 1815.6↤ 6 Butlin, William Blake 1757-1827, 251. Finally, the drawing we are considering here bears no trace of the interest in physiognomy that was the starting point of the Blake-Varley sketchbook. In short, despite Butlin’s association of A Vision: The Inspiration of the Poet with the Visionary Heads, the evidence, including that of his own meticulous catalogues, makes that association questionable.

We need not, however, attempt a final answer to the question of the drawing’s origin before venturing a hypothesis about its subject. As a perusal of Butlin’s entries for the Visionary Heads will demonstrate, virtually all of even these apparently free-form designs were illustrations of particular people, mostly from either British or biblical history, which means that the subjects were not very different from those of the rest of Blake’s drawings, though obviously their physiognomic focus gives many of them a close-up quality not found to the same extent in Blake’s other work. We can indeed find a very likely candidate for the subject of the present drawing in an appropriately Blakean source, the Bible.

In 2 Kings is an account of how the prophet Elisha used to be invited to eat bread at the house of a woman of Shunem. Perceiving that he was a man of God, she said to her husband: “Let us make a little chamber, I pray thee,

on the wall; and let us set for him there a bed, and a table, and a stool, and a candlestick: and it shall be, when he cometh to us, that he shall turn in thither” (4.10). In return, Elisha, through his servant Gehazi, called the woman to him and promised her a son, in spite of the age of her husband (4.12-16). I think it highly probable that the drawing represents Elisha seated in his “chamber . . . on the wall”; the odd phrase “on the wall” expresses exactly the relationship between the two spaces i the drawing, making it immediately intelligible.Butlin interprets the standing figure as representing “an angel . . . dictating begin page 129 | ↑ back to top to a seated figure writing,” but the photograph suggests strongly that what Butlin has taken to be the wing of an angel is in fact the shadow cast by the standing figure, who comes between the overhead lamp and the wall. There is no trace of a wing on the other side of the figure, and angels with only one wing are fortunately rare.7↤ 7 I should make it clear that I have not seen the original drawing, but am working from a very good photograph sent by the Tate Gallery which is not very much smaller (12 × 12.3 cm.) than the original (17 × 18 cm.). If we look again at the drawing with this hypothesis in mind, we can see a right angled line on the floor to the right of the table, which seems to mark off a space that could be interpreted as the kind of sleeping mat Blake sometimes shows, often in biblical contexts.8↤ 8 For examples, see Butlin, Paintings and Drawings #259, 320, 498, 550.11. The visual evidence is slender, but the line must represent something, and the interpretation I offer seems highly plausible. If this is accepted, we have all the elements mentioned in the woman’s account—the little chamber, a bed, a table, a stool (Elisha has to be sitting on something), and the candlestick. The fit between story and picture is a good one.

The moment depicted in the drawing is most probably that described in 4.15-16, when the woman has been summoned and appears “in the door.” Given the basic arrangement of the design, it would be impossible for Blake to have shown her actually “in the door,” for that would have required a view into an interior space that would have been very difficult to convey without fine detail and an elaborate perspectival scheme, neither of which was a favorite device of Blake’s. It would also have been a space at variance with the implications of the phrase “on the wall,” to which Blake appears to have given priority. It seems likely that Blake would have chosen the key moment of the story, and that is clearly the announcement by Elisha to the woman that she will “embrace a son”; though this son dies, he is subsequently brought back to life by Elisha (2 Kings 4.32-37). Elisha is the inheritor of the mantle of Elijah, “the Spirit of Prophecy the ever present Elias” (Milton 24.71); the subject of the drawing can therefore be identified as the initiating moment of an act of prophetic creation, the calling of life into being. The hitherto accepted title of this drawing, The Inspiration of the Poet, was not entirely incorrect.

This newly focused interpretation of the subject of the drawing also makes possible at least a partial explanation of its curious spatial organization. Rosenblum cites the drawing in the context of a discussion of the radical “dissolution of postmedieval perspective traditions” that occurred around 1800 as part of the quest for “an artistic tabula rasa” (189). Rosenblum’s approach to the whole question of style in the late eighteenth century is founded on the idea that the most vital currents in the changes taking place in the arts of the period “seem motivated by that late eighteenth century spirit of drastic reform which found its most radical culmination in the political revolutions of America and France” (146). This is described as leading to a variety of “regressions to what was imagined to be the pellucid dawn of pictorial art. . . .” (188), in an attempt to return to a kind of pre-Renaissance innocence. Since Rosenblum’s influential book was written, several writers moving over from the field of literature to that of the visual arts have taken his ideas about the art of this period further, and two in particular have given close thought to the relationships between style and meaning. Both begin from Rosenblum’s point that there are “many complementary and even contradictory currents” (146) available during this period, and develop from that perception the further idea that the choice of one style from the many potentially available is governed by the desire to communicate a particular kind of meaning.

One of these writers is W. J. T. Mitchell, who in an essay significantly titled “Style as Epistemology” uses Rosenblum’s insights to develop the suggestion that romanticism should perhaps be defined as “simply that historical movement which, in inventing the notion of a cultural history with discrete stylistic ‘periods,’ gathered all the possible artistic styles to its bosom in an eclectic stylchaos.”9↤ 9 W. J. T. Mitchell, “Style as Epistemology: Blake and the Movement toward Abstraction in Romantic Art” SiR 16 (1977): 146. From this stance Mitchell, with the help of further insights from Meyer Schapiro and E. H. Gombrich, develops the idea that a style is a “cognitive structure” (149), and that Blake’s particular forms of linear abstraction should be read as a kind of code, that style is indeed a part of the specific content or “statement” of a design (156), or, as Blake put it, “Ideas cannot be Given but in their minutely Appropriate Words nor Can a Design be made without its minutely Appropriate Execution . . . Execution is only the result of Invention” (PA, E 576).10↤ 10 On this whole issue in Blake, see Morris Eaves, William Blake’s Theory of Art (Princeton: Princeton UP, 1982) 79-169.

More recently Norman Bryson has suggested, in the course of a discussion of eighteenth-century French painting, that we need a history of painting as sign as well as the more conventional history of such painting as style. The reason he gives is that “in France the visual arts react not only towards and against specific visual styles, but towards and against the Académie and the high-discursive painting promoted by the Académie at different moments of its history.”11↤ 11 Norman Bryson, Word and Image (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1981) 239. I would suggest that this reason can be generalized; Blake, for instance, is in an analogous situation, seeing himself as one of the brave minority defending “high-discursive painting” against an environment that he interprets as supporting “bad (that is blotting and blurring) Art” (E 528). Bryson, like Mitchell, wants us to see style during the romantic period as governed by communicative desire, and chosen from among the “unprecedented array of styles” available to the painter at this time (240). Both critics, using Rosenblum’s original insights as part of the ground of their argument, end by asking us to read style as part of the process of meaning production rather than as an independent factor operating within its own closed system of historical transformation.

begin page 130 | ↑ back to topI shall use a brief account of what Bryson means by “high-discursive” as the path through which to resume discussion of the handling of space in Blake’s drawing, reading it this time as sign rather than style. Bryson begins his book by distinguishing what he calls the “discursive” elements of an image from the “figural” elements, defining the terms thus: “By the ‘discursive’ aspect of an image, I mean those features which show the influence over the image of language. . . . By the ‘figural’ aspect of an image, I mean those features which belong to the image as a visual experience independent of language—its ‘being-as-image’” (6). Out of this discussion comes an account of perspective as a structure which greatly expands the figural aspect of an image, ensuring that “the image will always retain features which cannot be recuperated semantically” (12-13). In doing this, however, perspective and the semantically neutral excess of information that it encourages risks the division of the image into two separable areas, “one which declares its loyalty to the text outside the image, and another which asserts the autonomy of the image. . . .” Under these conditions, “the image may risk appearing to be the disconnected base for a detachable superstructure” (13). In Blake’s language, Execution separated from Invention is in danger of producing an image characterized by “unorganized Blots & Blurs” (PA, E 576).

Looking at the drawing again from this vantage point, we can try to find more than stylistic meaning in the odd handling of space that drew Rosenblum’s attention. The key lies in remembering that it is this space—both the space that relates the small chamber to the surrounding room, and the apparent space that mediates between the chamber and the viewer—that visually determines the relationship between Elisha and the world around him, including ourselves. The handling of space in a design, in other words, is a form of visual rhetoric that shapes and directs information towards us, modifying it in the process.

The first thing that needs explanation is the obvious anomaly in the perspectival structure of the drawing. Rosenblum comments:

At first glance, the convergent perspective lines of the outer and inner sanctum seem to create two Renaissance box spaces of rudimentary clarity; yet. . . this simplicity is more apparent than real. Thus, the shading of the web-like component planes obeys no natural laws, but is manipulated in such a way that the would-be effects of recession are constantly contradicted, producing instead a series of simultaneously convex and concave planes whose shifting locations are matched in the history of art only by the comparable spatial and luminary ambiguities of early Analytic Cubism. (190)This offers a fascinating historical leap, and places the spatial handling of the drawing in a rich field of comment by isolating it from the other aspects of the work. But for the purposes of this essay I want to stay with the specific question of the handling of perspective a while longer, looking at it again begin page 131 | ↑ back to top in the light of the now identified subject and basic meaning of the drawing.

The vanishing point implied by the junction lines between the side walls and ceiling of the small chamber is incommensurable with that implied by the corresponding junction of the enclosing room; even Blake, with his ability to be careless about such things, must have been aware of the discrepancy.12↤ 12 I appreciate the force of Butlin’s remark that Blake was a “very uneven artist and many of his earlier works and scrappier drawings are almost totally lacking in technical merit,” but the discrepancy here is very obvious, and Mitchell and Bryson give us a new way of conceptualizing such matters. Martin Butlin, “Cataloguing William Blake,” in Blake in his Time, ed. Robert N. Essick and Donald Pearce (Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1978) 81. The angle formed by the junction in the outer rooms is so steep that it is unclear whether we are looking through a room with a deeply angled roof or at a strangely marked out planar surface; it is therefore also unclear whether the figures we see are small and close to us, or large and at some distance: our usual depth clues do not work properly under these conditions. The handling of perspective in the drawing contradicts the “would-be effects of recession,” as Rosenblum points out, and thereby makes the apparent space virtually indecipherable as space. There is also a conspicuous lack of the expected excess of figural information associated with perspectival structures in post-Renaissance western painting. Blake seems deliberately to have subverted the conventional functions of perspective, and has thereby almost forced us to read the spaces of the drawing as discourse rather than figure, in Bryson’s terms. Read in that way, the handling of space interprets and makes visible the relationship between the state of ordinary experience and that of prophetic inspiration; the two are closely related and in communication with each other, indeed one is in a sense inside the other, but they are also separated by the profound shift of gears necessary to move between them. That shift has been visually coded in the false perspective of the drawing.

The odd shading that Rosenblum comments on can also be read as discourse rather than figure. It suggests that while the light emanating from the little chamber cannot illuminate the wall that surrounds it, it has the power to project far into the room towards us, the spectators of the drama, as if to create a path connecting Elisha and the viewer. The light brightens the side walls, though it fades towards the corners of the room, which are darkened as if to frame the whole design. But there is a curious but symmetrical imbalance in this darkening—if we let our eye travel round the frame in a counter-clockwise direction, we find that the leading edge of each surface is light toned, while each trailing edge is comparatively dark, as if the shading is designed to suggest a rotational effect, almost the beginning of a vortical movement. The result is a dynamic emphasis on the centrality and power of Elisha’s chamber.

Rosenblum’s analysis is a very interesting one, and his comments on the primitivist and anti- or unillusionist trends of Blake’s art are well taken, as are those on Blake’s “technical regression to the linear and planar origins of art” (154-56, 187-89). But such commentary leaves unanswered the question why such trends find their strongest exposition in just this drawing, and indeed the larger question of why Blake is so attracted to this particular style among the many open to him at this moment. The interpretation offered above grounds the stylistic peculiarities of this drawing in its specific content, as part of the meaning of the drawing as a whole. A style can be understood as not so much the central determinant of a picture as one of several possibilities waiting in the wings to be called into action by an appropriate subject, and used for the semantic possibilities inherent within it.

Any reading of a design by Blake which has no accompanying title or text deriving from Blake himself must nearly always have a status a little below that of total certainty. Nevertheless, the reading outlined above seems extremely probable to me, and I would like to propose “Elisha in the Chamber on the Wall” as a new and appropriate title for this interesting drawing, that is now happily accessible in the public space of the Tate Gallery.