|

“an excellent saleswoman”: The Last Years of Catherine Blake Angus Whitehead (whitehead65_99@yahoo.co.uk) is assistant professor in English Literature at the National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. He is co-editor of Envisioning Blake, which will be published by Palgrave in February. | |||||||||||||

| 1 | Biographical information concerning any period of the life of Catherine Sophia Blake, née Boucher (illus. 1), remains lamentably sparse. However, few twenty-first-century scholars would agree with Mona Wilson’s comment, made about 1927, that “there is little independent record of Catherine Blake, nor is it needed.” [1] For the four years following Blake’s death, Catherine was the custodian and saleswoman of a varied and substantial collection of her husband’s works, as well as his drawing, painting, engraving, and printing materials. She was also a unique source for much information about his life and working practices communicated to Frederick Tatham, his fellow Ancients, and other friends and visitors. For almost forty-five years she was the person who lived and worked most closely with Blake, enabling him to realize numerous projects, impossible without her assistance. Catherine was an artist and printer in her own right, with firsthand knowledge and experience of Blake’s art practices. [2] And yet in surviving contemporary records written during and after her marriage, she was principally commended for her domestic role. [3] 1. Frederick Tatham’s drawing of Catherine Blake, “Septr. 1828.” … [+]

| ||||||||||||

| 2 | In the last two decades interest in and recognition of Catherine’s position in Blake’s life and work have grown. In 1993 Joseph Viscomi asserted her integral role in all aspects of Blake’s bookmaking projects. [4] In 2004 she was given her own entry in the new edition of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. [5] Eugenie R. Freed, in her review of Barbara Lachman’s fictionalized life, Voices for Catherine Blake: A Gathering (2000), observed: Like many of those interested in Blake’s work, I do feel the need to know a great deal more about Catherine Blake, an unsung heroine who has yet to be acknowledged as the courageous woman of many parts that she had to be in real life. [6] | ||||||||||||

| 3 | As this essay will demonstrate, scholars have yet to exhaust all avenues in reclaiming historical information concerning the life of Blake’s wife. Hitherto, the final four years of her life (1827-31) have received negligible attention from Blake’s biographers. Only G. E. Bentley, Jr., has attempted a detailed chronological reconstruction of where Catherine lived during those years. In the second edition of Blake Records he suggests that after six months living and working at 6 Cirencester Place, John Linnell’s town house and painting studio (Sept. 1827-c. Mar. 1828), the recently widowed Catherine lived, briefly, alone in lodgings at 17 Upper Charlotte Street, Fitzroy Square, before residing with Tatham and his wife at 20 Lisson Grove North (Apr. 1828-spring 1829). According to Bentley, she then returned to her former residence in Upper Charlotte Street. [7] | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Bentley’s reconstruction, based on contemporary data and informed guesswork, provides our most reliable picture of her last years to date. We can be certain that she lived at Cirencester Place for the first six months of her widowhood. [8] However, reliable information about the remaining three and a half years of her life is meager. A close inspection of Bentley’s chronology reveals that we really know little of Catherine’s life or whereabouts after she left Tatham in the early spring of 1829. Moreover, the precise nature of Tatham’s domestic arrangements is unknown. Bentley’s assertion that Catherine resided with and worked for Tatham and his wife at Lisson Grove, although apparently widely accepted, is based on circumstantial evidence and has not been fully investigated. Tatham’s wife, the “Mrs. Tatham” in whose arms Catherine died, [9] has not been identified, nor has any Blake biographer recovered the precise location of the last residence of Catherine Blake. Although it is clear that she resided at no. 17, it has not been established whether her final lodgings were in Charlotte Street, Upper Charlotte Street, Charlton Street, or Upper Charlton Street, Fitzroy Square. | ||||||||||||

| 5 | This essay presents and explores new information concerning the life, residences, and circle of Catherine Blake in the period immediately following her departure from Linnell’s town house, c. March 1828, until her death in mid-October 1831. It revises a number of Bentley’s assertions regarding the chronology and location of her residences. The essay will also explore her relationship with Frederick Tatham, the member of the Ancients with whom she had most contact after Blake’s death, and who—rightly or wrongly—inherited the Blakes’ earthly possessions after Catherine’s demise. | ||||||||||||

| 6 |

1. Catherine Blake in Widowhood, 1827-31 When William Blake died on the evening of 12 August 1827, Catherine was left a considerable number of unsold works [10] but little ready money, and she appears to have been unable to support herself. That day she was obliged to borrow five pounds from Blake’s patron Linnell. [11] In a letter to Linnell written two days later, John Constable expressed the hope that the Royal Academy would “do something handsome for the widow” and gave him advice as to how to apply to the academy’s benevolent fund on Catherine’s behalf. [12] Nevertheless, about a week after Blake’s death Catherine appeared intent on continuing to print from a rolling press, presumably in an effort to market her husband’s works and support herself. About 18 August James Lahee, copperplate printer of Castle Street, Oxford Market, wrote in response to a query from Linnell that he was willing to accept the Blakes’ old press: “if it happens not to be larger than Grand Eagle, and it is a good one in other respects I have one idle which would answer Mrs B’s purpose.” [13] However, the proposed project to swap presses appears not to have materialized, as four days later Linnell arranged for Blake’s star wheel rolling press to be moved from 3 Fountain Court to Cirencester Place. [14] Catherine followed two weeks after the press. | ||||||||||||

| 7 | During the period in which she lived with Linnell and then with Tatham, Catherine’s principal means of support derived from her performance of the duties of a domestic housekeeper. While at Cirencester Place she was also responsible for accepting money from Linnell’s customers when he was not at home. [15] Nevertheless, from the autumn of 1827 she began occasionally to sell her late husband’s works to visitors. With Linnell’s assistance, she sold Blake’s last commission, a name plate, as well as a copy of Illustrations of the Book of Job, to his old friend George Cumberland. [16] Catherine also attempted to encourage Cumberland to try to sell further copies of Job in Bristol, despite the fact that he had been unable to sell the copy he had received from Blake some months earlier. [17] | ||||||||||||

| 8 | Although on 8 December Linnell loaned Catherine a further five pounds, [18] a month later she was clearly beginning to establish a customer base for her husband’s works. On 8 January 1828 she sold three copies of “Chaucers Canterbury Pilgrims” to the judge and writer Barron Field and Blake’s acquaintance Henry Crabb Robinson (one of the copies was for Charles Lamb). On this occasion, Catherine agreed to look out other engravings. [19] On 17 March Mrs. Samuel Smith and Miss Julia Smith called on Catherine and paid eight guineas for Lear and Cordelia in Prison (1779) and A Female Figure Crouching in a Cave. [20] Alexander Gilchrist describes Catherine’s marketing skills as well as her finishing of Blake’s works during this period: She was an excellent saleswoman, and never committed the mistake of showing too many things at one time. Aided by Mr. Tatham she also filled in, within Blake’s lines, the colour of the Engraved Books; and even finished some of the drawings—rather against Mr. Linnell’s judgment. [21] | ||||||||||||

| 9 | About March 1828 Catherine moved to live with and work for Frederick Tatham. The numerous obituaries of Blake which appeared in the year following his death, followed by the publication of J. T. Smith’s Nollekens and His Times (1828), which featured a biography, appear to have enhanced Catherine’s chances of selling works. Smith wrote that “[Blake’s] beloved Kate survives him clear of even a sixpenny debt; and in the fullest belief that the remainder of her days will be rendered tolerable by the sale of the few copies of her husband’s works, which she will dispose of at the original price of publication.” [22] In early November he wrote to Linnell, “What I have said of your worthy friend Blake I am fully aware has been servisable [sic] to his widow.” [23] Later that month the barrister, antiquary, and art collector William Twopenny contacted Smith: My dear Sir, Can you tell me where the Widow of Blake the artist lives. Yours most truly Wm. Twopenny Temple 19. Nov. 1828 [24]Catherine’s business acumen, as well as her belief in vision and her husband’s continued presence, is perhaps apparent in her informing Linnell on 27 January 1829 that “Mr Blake told her he thought I shd. pay 3gs. a piece for the Plates of Dante—.” [25] | ||||||||||||

| 10 | By April 1829 Catherine was able to live independently in her own lodgings. This was almost certainly facilitated by a bequest of twenty pounds, furniture, and apparel from her brother-in-law and former landlord, Henry Banes, who had died in January. [26] Customers continued to approach her in order to purchase Blake’s works. On 11 April Tatham informed a potential patron: In behalf of the widow of the late William Blake, I have to inform you that her circumstances render her glad to embrace your Kind offer for the purchase of some of the works of her departed husband. … This elevated widow is now seeking a support during the remainder of her exemplary course, through the medium of the enlightened and the generous …. Should you, Sir, be inclined to possess, for the embellishment of your own collection, and the benefit of the widow, any of the enumerated works, they shall be carefully sent to you upon your remitting the payment, and I will take proper care that your Kindness shall be rewarded with the best impressions, and that you shall be used in a manner that shall not cause you to regret your absence from the scene of purchase. And communicating either with myself or Mrs. Blake, you will Receive her ample thanks and the acknowledgements of your obedient and humble Servant Frederick Tatham [27]About this time Catherine or Tatham sent to James Ferguson “a List of Works by Blake offered for sale by his widow.” [28] | ||||||||||||

| 11 | In July 1829 Catherine sold The Characters of Spenser’s “Faerie Queene” to the Earl of Egremont for eighty-four pounds, and on 1 August she left the work, together with a “descriptive Paper,” at his town residence in Grosvenor Place. [29] The sale provided further financial security. In early 1830 Allan Cunningham’s life of Blake appeared in volume 2 of his Lives of the Most Eminent British Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, and the discussion provoked in newspapers and journals ensured that Blake’s name, as well as Catherine’s, reached an even wider audience. [30] By the summer of 1831 she was probably too ill to print, color, or sell Blake’s works. Gilchrist describes the stock in Catherine’s possession at her death as “still considerable.” [31] | ||||||||||||

| 12 | In addition to selling Blake’s works, Catherine, an accomplished operator of a rolling press, [32] printed from the large number of copperplates in her possession. According to J. T. Smith, Blake “allowed her, till the last moment of his practice, to take off his proof impressions and print his works, which she did most carefully, and ever delighted in the task.” [33] Around 1827 Catherine, perhaps assisted by Linnell, may have utilized Blake’s old press at Cirencester Place to take proofs of the Dante plates. [34] Bentley states that later “she and Tatham printed Blake’s copperplates of America, Europe, Jerusalem, and the Songs ….” [35] For the Sexes copies E-I were probably printed by either Catherine or Tatham. [36] She also appears to have colored and finished Blake’s prints, drawings, and other works from stock. Essick observes that “she may have completed several of Blake’s projects, left unfinished at his death, including his watercolour illustrations to Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress.” [37] In addition, while at Tatham’s Catherine produced at least one painting of her own, a watercolor of a head “taken from something she saw in the Fire …” (illus. 2). [38] 2. Catherine Blake, Head “taken from something she saw in the Fire.” … [+]

| ||||||||||||

| 13 | According to Gilchrist, “the poet and his wife did everything in making the book,—writing, designing, printing, engraving,—everything except manufacturing the paper: the very ink, or colour rather, they did make.” [39] Smith observes that both William and Catherine colored “the marginal figures up by hand in imitation of drawings.” [40] Tatham records that Catherine laboured upon [Blake’s] Works[,] those parts of them where powers of Drawing & form were not necessary, which from her excellent Idea of Colouring, was of no small use in the completion of his labourious designs. This she did to a much greater extent than is usually credited. [41]His statement suggests that she had the experience and ability to color her husband’s works confidently and more than competently after his death. | ||||||||||||

| 14 | This evidence suggests that Catherine could print, color, and finish her husband’s works and sell a respectable number to a growing customer base. However, the precise location of Tatham’s residence where she lived and worked from 1828 to 1829 has received little attention. | ||||||||||||

| 15 |

2. Catherine Blake’s Residence with Frederick Tatham, c. March 1828-April 1829 On Linnell’s departure during the spring of 1828 from Cirencester Place to his new family home and studio at 26 Porchester Terrace, Bayswater, Catherine moved to the residence of her friend Tatham. [42] In his “Life of Blake,” completed c. 1832, Tatham wrote: After the death of her husband she resided for some time with the Author of this[,] whose domestic arrangements were entirely undertaken by her; until such changes took place that rendered it impossible for her strength to continue in this voluntary office of sincere affection & regard. [43]However, her working and domestic relationship with Tatham probably differed from that which she had experienced with Linnell. While using Cirencester Place as a studio during the week, Linnell spent the majority of his free time, weekends, and evenings with his wife and young family at their farm cottage at North End, Hampstead. [44] During these periods Catherine Blake was a house sitter, relaying messages concerning customers and other callers to Linnell via nephews in his employment. [45] She may have been similarly employed at Tatham’s. However, whereas Linnell appears to have paid her twenty pounds for her six-month employment at Cirencester Place, [46] Tatham describes her role as a “voluntary office.” | ||||||||||||

| 16 | She seems to have enjoyed a closer relationship with Tatham than with Linnell. While he does not mention remunerating Catherine, he probably treated her in her “voluntary office” as a friend or guest rather than as a servant or dependent. He uses the phrase “maternal loveliness” to describe the nature of her role. [47] Catherine was in her sixties and childless with only two surviving relatives, while Tatham was approximately twenty-three. A quarter of a century earlier, a former fellow resident and wife of the Blakes’ first landlord at South Molton Street, “the young & very amiable Mrs Enoch. … gave [Catherine] all the attention that a daughter could pay to a mother.” [48] Tatham may have found himself filling a similar role as surrogate son. | ||||||||||||

| 17 | Catherine may have had another reason for her “maternal loveliness.” During this period Tatham appears to have suffered from a debilitating mental and physical illness, causing his family and friends considerable concern. In a letter to George Richmond dated 12 May 1827, Samuel Palmer wrote “Pray Sir bring a very particular account of Mr Tatham’s health.” [49] Tatham was still ill three months later when he traveled ninety miles to attend Blake’s funeral on 17 August. [50] In October 1828 Palmer wrote to Richmond, “I am rejoiced to hear that Mr Tatham is much better.” [51] A letter to Linnell from Tatham’s father, the architect Charles Heathcote Tatham, in early 1828 seems to suggest that Frederick was suffering from a long-term and recurrent illness: I hear you still consult that Top-sawyer [eminent personage] Thornton. He has been a thorn in my side; but I endeavour to forget his unsuccessful and expensive experiments upon my poor son. [52]Catherine Blake may therefore have spent at least part of her time performing the duties of a sick nurse and carer, as she had for her husband less than a year earlier. | ||||||||||||

| 18 | Catherine’s “voluntary” service for Tatham may have derived in part from affection for a young man who, despite personal inconvenience both in distance and health, had attended Blake’s funeral and shown care and concern for her in the first six months of her widowhood. Tatham and his wife would later nurse and attend Catherine at her deathbed, and she died in Tatham’s wife’s arms. The couple organized, attended, and almost certainly paid for her funeral, which she requested should follow the form of her husband’s four years earlier. [53] Linnell, by contrast, appears not to have been present at either funeral, possibly because both were conducted according to the Church of England’s service for the burial of the dead. As a strong-minded dissenter who had traveled to Scotland in order to avoid a Church of England marriage ceremony, he appears to have preferred to offer Catherine financial assistance. [54] | ||||||||||||

| 19 | In his “Life of Blake” Tatham does not specify his address during the period of Catherine Blake’s residence with him, nor does he provide precise information concerning the length of her stay. He simply states that she lived with him “for some time.” Until 1969, no Blake biographer had discussed either the location or the duration. In the first edition of Blake Records, however, Bentley asserted that from 1828 until 1831 Catherine resided with Tatham and his wife at 20 Lisson Grove North, northwest London. [55] During the running dispute with Linnell concerning ownership of the Dante watercolors and plates, Tatham corresponded from this address on 15 March 1831 and again, twice, on 1 March 1833. [56] Lisson Grove North is also the address he gives at the end of his “Life of Blake,” written c. 1832. [57] This, therefore, was certainly his residence during the period 1831-33. Bentley appears to have concluded that Tatham had resided there with Catherine three years earlier. However, an examination of the Marylebone poor rate book entries reveals that neither Frederick Tatham, Mrs. Tatham, nor Catherine Blake lived at this address in spring 1828. | ||||||||||||

| 20 | According to the rate book for 1828, the year Catherine moved to Tatham’s residence, the ratepayer for 20 Lisson Grove North was Edward Sewell. [58] Pigot’s Directory for the same year reveals that Sewell, a carpenter and builder, ran his business from the property, a house “and shops.” [59] The following year, the address had no recorded ratepayer; [60] it was almost certainly unoccupied. Further evidence suggests that Tatham did not move to Lisson Grove North before 1830. As discussed earlier, on 11 April 1829 he wrote from “34. Alpha Road. Regent’s Park. London” in reply to a potential patron who had expressed interest in purchasing copies of Blake’s works from Catherine. [61] This was the residence of his father. [62] | ||||||||||||

| 21 | It is also unlikely that Tatham and Catherine lived at 20 Lisson Grove during the first half of 1830. In Clayton’s Court Guide for 1830, “F. Tatham Esq.” is listed as residing in Alpha Road, presumably with his father at no. 34. [63] The Marylebone rate books reveal that the ratepayer for 20 Lisson Grove North that year was “Wm. Eales”; Robson’s Directory for 1830 records “William Eales, Timber Merchant” as conducting business there. [64] | ||||||||||||

| 22 | Tatham appears as ratepayer at 20 Lisson Grove North in 1831, [65] the year that he is first recorded at this address in a trade directory: Robson’s Directory for 1831 includes “Frederick Tatham, Statuary & Marble works, 20 Lisson Grove.” [66] It seems clear that he did not live and work there before mid- to late 1830, so his residence c. March 1828, when Catherine moved from Linnell’s, must have been elsewhere. | ||||||||||||

| 23 | During the period 1829-30 Tatham was spending a significant amount of time at 34 Alpha Road with his parents and numerous siblings. It could be argued that, as he was probably living there during the spring of 1828, Catherine moved from Cirencester Place to stay with the entire family at this address. She could have acted as housekeeper and helped look after C. H. and Harriet Tatham’s younger children: 17-year-old Julia, 15-year-old Harriet, 14-year-old Augusta, 11-year-old Maria, 8-year-old Georgiana, 6-year-old Edmund, and 4-year-old Robert Bristow. [67] However, this seems unlikely. In his “Life of Blake” Tatham recalled that his “domestic arrangements were entirely undertaken” by Catherine. Gilchrist, who interviewed Tatham about 1860, refers to his residence as “chambers,” [68] a description which suggests a professional working environment, probably for a bachelor. Tatham is perhaps recollecting a period in which he lived, at least part of the time, alone in his own residence. As we shall see, 34 Alpha Road was not Tatham’s sole residence in 1828. | ||||||||||||

| 24 | Tatham’s letter of 11 April 1829, discussed earlier, indicates the period in which he and Mrs. Blake shared the same address. Heading his letter 34 Alpha Road, he describes Catherine as living independently in lodgings near Fitzroy Square. [69] This suggests that she and Tatham shared an address from c. March 1828, when she left Cirencester Place, until no later than the beginning of April 1829, barely a year. In the following paragraphs a more probable location for their residence will be suggested. | ||||||||||||

| 25 | In 1824 Tatham was awarded a silver palette by the Society of Arts “for a [plaster] model of a figure from antique”; [70] he exhibited A Negro’s Head and The Angel Gabriel—A Sketch at the Royal Society of British Artists in 1829. [71] In both cases his address is given as “1 Queen Street, Mayfair,” [72] the location of his father’s practice as an architect, 1809-33. [73] Frederick almost certainly used rooms or “chambers” above his father’s practice as his painting and sculpture studio and residence. This upper-floor residence in Queen Street is probably the address to which Catherine Blake moved in the spring of 1828. | ||||||||||||

| 26 | In a letter to Linnell written from 1 Queen Street on a Friday towards the end of 1828, C. H. Tatham refers to leaving home in Alpha Road that morning in order to travel to work at his offices in Queen Street: “Had the weather been tolerable, I should have walked up to you; and hesitated some time this morning before I quitted Alpha Road.” [74] Another letter to Linnell, written two years earlier, suggests that both C. H. and Frederick Tatham had slept at Alpha Road the previous night: Queen Street, Mayfair, Monday May 1 Dear Linnell, I am fully confident and very grateful to you for your friendship and kind offices to my dear Frederick—The distance between my house and yours is great and much time is necessarily consumed in walking to and fro but as I was last night kept up till half past 11 o’clock in anxious suspense for his return, for a good hour—will you assist me to persuade him in future in the way you can very kindly do, not to stay so late—As I grow older I am not less nervous—You can consider this private. Yours ever, C.H.T. [75]Just as Linnell had used Cirencester Place as his studio and spent his free time with his family at Hampstead until spring 1828, Frederick Tatham in all probability spent his working hours at his studio on an upper floor in Queen Street but stayed with his parents and siblings at Alpha Road at weekends and on occasion overnight during the week. If this was the case, Catherine Blake may have spent only a limited amount of time in Tatham’s company. As C. H. Tatham paid the rates, Catherine would technically have been his lodger. It is therefore likely that Tatham Sr. played an instrumental role in sheltering and employing her. [76] | ||||||||||||

| 27 | By the spring of 1828 Catherine Blake and C. H. Tatham had known each other for over a quarter of a century. The frontispiece to America copy B is inscribed “From the author to C H Tatham Octr. 7 1799.” [77] It also seems likely that Blake was a subscriber to two of the elder Tatham’s works, published in 1799 and 1802. [78] In a letter to Linnell of 1824, Tatham Sr. referred to his old friend as “Michael Angelo Blake.” [79] Indeed, despite Linnell’s claim that he introduced Frederick Tatham to Blake, [80] Frederick’s acquaintance with William and Catherine was more likely the result of the Blakes’ long-standing friendship with his father. | ||||||||||||

| 28 | Sometime after 1820, Catherine attached a note in her own hand to a copy of Blake’s engraving of the celebrated Plymouth divine Rev. Robert Hawker: Mr C Tatham The humble is formed to adore; the loving to associate with eternal Love C Blake [81]It is unclear when she inscribed the note and when the print was presented. In the first edition of Blake Records Bentley claimed that Blake presented it in August 1824 because “Aug. 4th, 1824 is the only time after 1820 when Blake and C. H. Tatham are known to have been together.” [82] In fact they met on at least one subsequent occasion; according to Blake’s letter to Linnell of 15 March 1827, C. H. Tatham visited 3 Fountain Court the previous day. Blake writes: I saw Mr Tatham Senr yesterday he sat with me above an hour & lookd over the Dante he expressd himself very much pleasd with the designs as well as the Engravings. [83]Catherine could therefore have given him the engraving during this visit. As Bentley (more recently) and Essick have observed, however, the fact that the note is signed by Catherine suggests that the engraving was presented during the period of her widowhood. [84] | ||||||||||||

| 29 | As C. H. Tatham paid the rates at 1 Queen Street, Frederick must have consulted his father before inviting Catherine to live and work there. It seems probable that during the spring of 1828, approximately a year after his last recorded visit to Fountain Court, Tatham Sr. assisted his eldest son in providing a home for his old friend Catherine Blake. [85] If this was the case, Catherine could have presented him with the engraving during her residence there, c. March 1828-April 1829. [86] If Blake’s old press had been set up in Frederick’s chambers, she may even have printed a fresh impression of the plate. | ||||||||||||

| 30 |

3. Catherine Blake: Housekeeper to Mr. and Mrs. Frederick Tatham or to Frederick Tatham, Bachelor? Bentley states in the first edition of Blake Records that “Catherine Blake lived as housekeeper to Frederick Tatham and his wife.” [87] In the final section of his “Life of Blake,” Tatham mentions his wife’s relationship with Catherine: [Catherine] was followed to her grave by 2 whom she dearly loved, nay almost idolized, whose welfare was interwoven with the chords of her life & whose well being was her only solace, her only motive for exertion & her only joy. The news of any success to them was a ray of Sun in the dark twilight of her life. Their cares were hers, their sorrows were her own. To them she was as the fondest mother, as the most affectionate Sister & as the best of friends[;] these had the satisfaction of putting into her trembling hands the last cup of moisture she applied to her dying lips & to them she bequeathed her all. [88]He refers to his wife more explicitly in a letter to Linnell sent on the day of Catherine’s death, 18 October 1831: “Mrs Tatham & myself have been with her during her suffering & have had the happiness of beholding the departure of a saint for the rest promised to those who die in the Lord.” [89] Gilchrist states that Catherine “died in Mrs. Tatham’s arms.” [90] These accounts establish the Tathams’ presence as regular visitors at her last residence, overnight attendants at her deathbed, and two of the six friends who attended her burial at Bunhill Fields on 23 October. However, they provide no evidence for Bentley’s suggestion that upon leaving Cirencester Place Catherine became housekeeper to Mr. and Mrs. Frederick Tatham. | ||||||||||||

| 31 | In July 1927 the biographer Henry Curtis asked in Notes and Queries, “Can any reader supply the dates of marriage and death, as also the parentage and maiden name of the wife of Frederick Tatham, eldest son of Chas. Heathcote Tatham, 1772-1842, a famous architect?” [91] His query appears to have remained unanswered. In the index to the second edition of Blake Records, Tatham’s wife is referred to as “Tatham, Mrs Frederick.” [92] | ||||||||||||

| 32 | However, recently discovered information establishes that Mrs. Tatham did not live at the same residence as Frederick Tatham and Catherine Blake, c. March 1828-April 1829. The register of St. Mary Stratford Bow records that Frederick married Louisa Keen Viney on 25 April 1831, less than six months before Catherine’s death. [93] It is clear, therefore, that Catherine’s relationship with Louisa Tatham did not involve acting as her housekeeper. | ||||||||||||

| 33 |

4. Catherine Blake’s Move to Her Own Lodgings As has been established, Tatham wrote a letter from Alpha Road in April 1829 providing his correspondent with Catherine’s new address, so she must have left by spring 1829 and possibly several months earlier. By c. February 1829 she had sufficient funds and furnishings to support a move to her own lodgings. According to the will of her brother-in-law and former landlord, Henry Banes, proved on 14 February, she was to receive “half my household goods consisting of Bedsteads Beds & pillows Bolsters & sheets & pillow Cases Tables Chairs & crockery & £20 in lawful money of Great Britain.” [94] Banes, who died on 20 January 1829, may have informed the Blakes of his intention to leave them a portion of his money and goods when he wrote a new will on 9 December 1826. [95] At that time, the Blakes were lodgers in his house at 3 Fountain Court, Strand. Two years later, this bequest would have enabled, and may even have prompted, Catherine’s move. It contributed to what Bentley has described as her “new-found financial security.” [96] Moreover, in letters of August 1829 to George O’Brien Wyndham, third Earl of Egremont, she gave advice on the application of a third coat of varnish to the design from Spenser’s Faerie Queene, which he had purchased in July for eighty-four pounds. As Bentley has observed, this generous payment would have “kept Catherine out of want for the rest of her life.” [97] Significantly, in January 1830 she requested that an application to the Artists’ General Benevolent Institution be withdrawn. [98] | ||||||||||||

| 34 | It seems likely, therefore, that Catherine Blake moved to her own lodgings near Fitzroy Square, her final earthly residence, by the spring of 1829. However, the length of time that she spent there means that the dating of some events must be less precise than has previously been suggested. One such incident is Tatham’s difference of opinion with her which culminated in his burning Blake’s “will” at her lodgings. [99] Bentley, following his chronology of her last residences in the first edition of Blake Records, claims that “the incident took place in 1831.” [100] However, the revised dating suggests that the disagreement could have occurred at any time between early spring 1829 and October 1831. [101] | ||||||||||||

| 35 | One significant problem relating to the chronology of Catherine’s residences remains. Tatham claims that, after leaving his residence, “[Catherine] then returned to the lodging in which she had lived previously to this act of maternal loveliness [i.e., acting as housekeeper to Tatham].” However, he mentions no place in which she lived after Blake’s death other than his own: “After the death of her husband she resided for some time with the Author of this.” [102] Tatham does not refer to either Linnell or his town house and studio at 6 Cirencester Place, Fitzroy Square, where Catherine lived until spring 1828. [103] Bentley appears to interpret his statement as suggesting that Catherine lived in the same flat both before and after her stay with Tatham. [104] It is unlikely, however, that she would or could have returned to exactly the same lodgings. More significantly, the sequence of residences that I have outlined above makes it improbable that Catherine could have spent any period of time living independently between leaving Cirencester Place and moving to Queen Street. Rather, Tatham’s confusing and inaccurate statement suggests an attempt to skate over uncomfortable facts. [105] At the time that he wrote his manuscript biography of Blake (c. 1832), he and Linnell were no longer on speaking terms. Their alienation was due firstly to a difference of opinion concerning ownership of Blake’s Dante watercolors and plates that surfaced in the first half of March 1831. Secondly, Tatham’s claiming the Blakes’ entire estate on Catherine’s death in October 1831 appears to have annoyed Linnell, who supported the claim of Blake’s sister. [106] Tatham may not have wished to revive recent memories of distasteful arguments or draw attention to his conduct in dealings with Catherine and Linnell. | ||||||||||||

| 36 | We must also consider the significance of a meeting between Linnell and Tatham recorded in Linnell’s journal for 29 March 1828: “Mr F. Tatham dined at Hampstead.” David Linnell interprets this as evidence that [Linnell] asked Frederick Tatham to dine with him to discuss where Mrs Blake should live once he had let Cirencester Place. Frederick Tatham suggested that Mrs Blake should move into his house and this was then arranged. [107]The date of the entry gives some plausibility to David Linnell’s reading. As has been established, Catherine probably lodged with Tatham for a year or less. If she resided in her own lodgings between leaving Linnell’s and moving to Tatham’s, her stay must have been extremely brief. | ||||||||||||

| 37 | Significantly, after living with Tatham, Catherine appears to have chosen to return to the environs of Fitzroy Square, to the street parallel to Cirencester Place. Perhaps this is what Tatham meant when he refers to her returning “to the lodging in which she had lived previously.” She may still have known friends and potential customers in the neighborhood whom she had met while living under Linnell’s roof. The sculptor and book illustrator Maria Denman and her brother Thomas, sister- and brother-in-law of John Flaxman, lived at 7 Buckingham Street, Fitzroy Square. [108] Thomas Butts, Blake’s patron for many years and still a customer and visitor in Blake’s last years, was at 17 Grafton Street, on the corner of Fitzroy Street and Grafton Street on the edge of Fitzroy Square, two blocks from Catherine’s new lodgings. [109] John Constable, who had expressed great concern for Catherine’s welfare at the time of Blake’s death, lived at 35 Charlotte Street, Fitzroy Square. [110] The sculptor Joseph Denham (or Dinham), whom Tatham describes as a friend of Catherine’s and a mourner at her funeral, [111] also lived nearby, at 7 Cleveland Street. [112] Another friend who was among the six who attended the funeral, according to Tatham, was “Mr. Bird Painter”: Isaac F. Bird, the Exeter portrait painter who in 1831 lived at 37 London Street, one block south of Fitzroy Square. [113] | ||||||||||||

| 38 | For the majority of her widowhood (spring 1829-October 1831) Catherine lived independently. With her financial security ensured by the bequest from Banes and the gift purchase from Lord Egremont, she was able to support herself by printing, coloring, and selling her husband’s works, not merely for a few months but for approximately two and a half years. In the next section the precise address of her final residence will be established. | ||||||||||||

| 39 |

5. The Location of Catherine Blake’s Last Residence and Studio In the “Life of Blake” Tatham does not provide the address of Catherine’s last lodgings. Gilchrist records that “finally, she removed into humble lodgings at No. 17, Upper Charlotte Street, Fitzroy Square, in which she continued till her death; still under the wing, as it were, of this last-named friend [Tatham].” [114] In the numerous biographies of Blake since Gilchrist, the location of this final residence has not been conclusively identified. Arthur Symons, Mona Wilson, Thomas Wright, and most recently Jack Lindsay and James King have followed Gilchrist. [115] Bentley, however, citing correspondence from Tatham to Linnell and the Bunhill Fields burying ground order book, asserts in the first edition of Blake Records that the lodgings were at “17 Charlton Street,” [116] a claim repeated in Blake Records Supplement and The Stranger from Paradise. [117] Peter Ackroyd and Robert Essick have also located Catherine’s last residence at this address. [118] In the second edition of Blake Records, Bentley states in the appendix of residences that Catherine “lodge[d] with a baker at 17 Upper Charlotte Street, south-east of Fitzroy Square,” [119] but the title of the section reveals some uncertainty: “17 Upper Charlotte or Charlton Street.” In a footnote Bentley observes that there is some ambiguity about the name of the street; it is called “Upper Charlotte Street” in Tatham’s letter of 11 April 1831 [i.e., 1829] and in Gilchrist … but “Upper Charlton Street” in Tatham’s letter of 18 Oct 1831 and in the documents for Catherine’s burial on 20 Oct 1831. [120] | ||||||||||||

| 40 | Catherine’s final residence was in fact at 17 Upper Charlton Street, a block southwest of Fitzroy Square. This is the address on the two letters sent by Catherine to Lord Egremont in August 1829, [121] and it is also cited in the record for her burial at Bunhill Fields. [122] More recently, Butlin refers to this address in his Paintings and Drawings of William Blake. [123] Although the information seems widely known, the issue of Catherine’s last address has not been laid to rest in any biography of Blake. | ||||||||||||

| 41 | The substitution of Charlotte for Charlton in several of the documents cited above by Bentley might be explained by the ease with which one can mistakenly be written for the other (an error I have made several times while researching this paper). The only contemporary reference to Upper Charlotte Street appears in the transcription of Tatham’s letter of 11 April 1829, [124] where a mistranscription of the word Charlton could easily have been made. More significantly, the omission of Upper from Upper Charlton Street in discussions of Catherine’s last address and the suggestion that she lived at 17 Charlton Street have led to a small but important error in locating the residence. Although, as one would expect, Upper Charlton Street was directly north of and a continuation of Charlton Street, the two were individually numbered and were in effect separate streets (see illus. 3). However, Catherine’s contemporaries and early biographers used the names Charlton Street and Upper Charlton Street interchangeably, or transcribed Charlton as Charlotte, and in the process the precise location of her last residence was muddled. 3. Section of Horwood’s map of London (London: W. Faden, 1813). … [+]

| ||||||||||||

| 42 | In 1830 Cumberland wrote on his copy of For Children: The Gates of Paradise, “Mrs Blake now lives at N 17 Charlton St Fitzroy Square at a Bakers.” [125] When contemporary directories or rate books are consulted, the last three words of his note make no sense. Bentley records a Henry Heather as ratepayer at this address, [126] but in directories H. C. Heather is listed as conducting business at 17 Charlton Street not as a baker but as a bootmaker. [127] But an examination of directories and rate books for 17 Upper Charlton Street reveals that although Cumberland erroneously recorded the address, he does appear to have been correct concerning the business: in 1829, Thomas Mason ran a bakery from, but was not ratepayer at, 17 Upper Charlton Street. [128] From 1830 onwards another baker, George Miller, occupied 17 Upper Charlton Street [129] and, unlike his predecessor, was also ratepayer for the property. Such evidence appears to confirm the identification of Catherine’s last residence. [130] | ||||||||||||

| 43 | Two further points concerning her lodging at this address may be deduced. If, as the rate books suggest, the baker Thomas Mason and his landlord William Barlter vacated 17 Upper Charlton Street sometime before mid-1829, at least two living spaces were left free. The new landlord, George Miller, may therefore have advertised for lodgers during the period in which Catherine received her bequest from Henry Banes and began searching for new lodgings in anticipation of Tatham’s move to Lisson Grove North. It could also be argued that a change in landlord throws additional doubt upon Bentley’s suggestion that Catherine occupied the same lodgings both before and after residing with Tatham. It seems unlikely that she could have lived briefly at this address in the spring of 1828 and then have returned at a later date to the same house, which in the intervening period had been taken over by a new landlord. | ||||||||||||

| 44 | Linnell would have been familiar with 17 Upper Charlton Street: in his “Autobiography” he recalls that the artist William Mulready “was really my tutor in everything my companion playmate and guide … my character was formed by him.” [131] He also indicates that in “1807—Mullready lived in Upper Charlton Street, Fitzroy Square,” and observes that “this is where I saw him often and spoke to him about being his pupil He making designs at this time for Godwin.” [132] The catalogue for the exhibition at the Royal Academy in 1807 reveals that Mulready’s lodgings and studio were at no. 17, presumably on an upper floor. [133] Linnell spent one of his formative years learning his craft from a painter in a house that was later to become the lodgings of Catherine Blake. The connection with Linnell may even suggest that Blake’s patron played some role in locating a new residence for Catherine in early 1829. | ||||||||||||

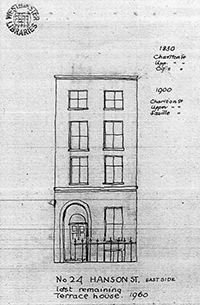

| 45 | The fact that Mulready had previously occupied 17 Upper Charlton Street for a year over two decades earlier may seem of little importance. However, his use of a room in this house as a painting studio suggests that Catherine could have printed, colored, and sold Blake’s work there. Although Gilchrist describes the lodgings as “humble,” the rateable value of the property was sixty pounds, the highest in the street [134] and considerably more than twice the value of the Blakes’ final residence together at 3 Fountain Court. I have been unable to find a floor plan or front elevation of no. 17, but an Ordnance Survey map of the area, published in 1872, reveals the footprint of the building (illus. 4). In addition, a sketch of the front elevation of one of the terrace houses on the east side of Upper Charlton Street has been located at the City of Westminster Archives Centre (illus. 5). From this evidence we may deduce that no. 17 was a Georgian terrace with two rooms on each floor, a large front one and smaller back one. Catherine may have organized her space, almost certainly an upper-floor apartment, [135] along the lines of her and her husband’s rooms at 17 South Molton Street and 3 Fountain Court. [136] She may have received visitors in the smaller living room at the back of the house; a larger front room may have been used to store her stock of Blake’s paintings, engravings, and drawings. It is likely that she would also have had room for the furniture inherited from her brother-in-law. Whether or not she moved into the rooms that Mulready had utilized, the orientation and light would have been the same. As Mulready probably chose the residence as suitable for a painting studio, in her front room Catherine almost certainly had adequate light and space to set up her own studio for coloring works and perhaps even for printing on a rolling press. [137] In the front room, with Tatham’s assistance, she may have printed posthumous copies of Blake’s illuminated books. The scaled representation of the footprint of no. 17 on the 1872 survey map reveals that the front rooms on the upper floors measured approximately 5.49 meters (18 feet) in width and 3.66 meters (12 feet) in depth. This means that for over two years, Catherine, living independently, had space to color and sell her late husband’s works and could also resume her role in printing copies of his illuminated books. [138] 4. Upper Charlton Street in a detail of the Ordnance Survey map, 1872. … [+]

5. Front elevation of a house in Upper Charlton Street (later renamed Hanson Street). … [+]

| ||||||||||||

| 46 |

Conclusion The material presented in this paper gives us cause to revise the chronology of the residences and microcultures that Catherine Blake lived in from 1828 to 1831 (see table below). It has demonstrated that she did not spend the majority of her final years as housekeeper to Frederick Tatham and his wife at their house in Lisson Grove North. Evidence suggests that she resided as housekeeper with Frederick, a bachelor, in chambers above her old friend C. H. Tatham’s practice as an architect at 1 Queen Street, Mayfair, from March 1828 until the early spring of 1829. Catherine’s close young female friend, the wife of Frederick, has been identified as Louisa Keen Viney Tatham. Evidence has also been provided to support the argument that Catherine had the means to and almost certainly did move to her own lodgings in or shortly before the spring of 1829. Finally, the precise location of her “humble lodgings,” 17 Upper Charlton Street, Fitzroy Square, has been established. The residence and the duration of her stay provided her with the opportunity to sell Blake’s works, finish and color others, and perhaps print posthumous copies of the illuminated books, and thereby live independently for the last two and a half years of her life.

| ||||||||||||

| 47 | In the light of these findings, we can also revise our view of Catherine. She was not a dependent Blake relict, reliant upon his old friends and passed from Ancient to Ancient. Upon inheriting Banes’s bequest, she embarked at the age of sixty-seven on a period of independence, possibly for the first time in her life. On an upper floor at 17 Upper Charlton Street, she appears to have continued her husband’s trade, printing, coloring, and selling works up until her death, over a year into the reign of William IV. In this constant labor in old age, she perhaps followed her husband’s maxim of working through illness. [139] Such unremitting industry may account for her having neglected a bowel complaint that led to her death. | ||||||||||||

| 48 | This emerging picture seems consistent with Essick’s suggestion that during Blake’s lifetime Catherine was “the more practical of the two,” [140] and Mark Crosby and Essick’s discussion of Blake’s tribute to her in response to William Hayley’s “Klopstockian” compliment. [141] Contemporary and early accounts portray Catherine as on occasion unstable, difficult, miserable, and ill. Blake’s own reported behavior may lead us to suspect that their working and emotional partnership cannot have been uniformly efficient or idyllic. Nevertheless, Catherine must also have exhibited during her marriage to Blake the resilience and financial acumen evident in her later widowhood—to the couple’s advantage. | ||||||||||||

|

Notes Earlier versions of the paper were presented at the Blake at 250 conference, University of York, 30 July-1 Aug. 2007, the Romantic Biographies conference, University of Keele, 8 May 2009, and the session on Recovering the Historical Catherine Blake, 1762-1831, MLA convention, Los Angeles, 7 Jan. 2011. Much of the material derives from chapter 8 of my PhD thesis, “New Discoveries Concerning William and Catherine Blake in Nineteenth Century London: Residences, Fellow Inhabitants, Neighbours, Friends and Milieux, 1803-1878,” University of York, 2006. For kind assistance and support during the research and writing of this paper I wish to thank the staff of New Stratford Library, New Stratford, London, Kate Davies, David Alexander, Troy R. C. Patenaude, my friend and fellow student at York, and especially my thesis supervisor, Michael Phillips. 1. Mona Wilson, The Life of William Blake (1927; ed. Geoffrey Keynes, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1971) 368. 2. In a letter to George Richmond, Samuel Palmer recommends “Mrs. Blake’s white” as an effective art medium. See Raymond Lister, ed., The Letters of Samuel Palmer, vol. 1 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1974) 38. 3. In a letter to Richard Monckton Milnes, first Baron Houghton, c. 1870, the painter, antiquary, and visionary Seymour Kirkup described Catherine as “as good as a Servant” (G. E. Bentley, Jr., Blake Records, 2nd ed. [New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004] [hereafter BR(2)] 294). She had probably been in service as a maidservant before marrying (see BR[2] 71). There is an account of there being a servant at the Blakes’ house in the early period of their residence at 13 Hercules Buildings, Lambeth, in the 1790s. However, according to Tatham, Catherine soon took over those duties: “(as Mrs. Blake declared …) the more service the more Inconvenience” (“Life of Blake,” quoted in BR[2] 676). 4. See, for example, Joseph Viscomi, Blake and the Idea of the Book (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993) 102-03. 5. Robert N. Essick, “Blake, Catherine Sophia,” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography [hereafter ODNB], Oxford University Press, 2004 <http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/64608>, accessed 19 Apr. 2006. 6. Eugenie R. Freed, Blake 36.4 (spring 2003): 151. 7. BR(2) 754-55. Under the heading for 17 Upper Charlotte or Charlton Street, Bentley says that “she had returned to Upper Charlotte Street by the spring of 1829”; under 20 Lisson Grove, he gives Apr. 1828-early 1830 for her residence with the Tathams, but he corrects 1830 to 1829 in addenda to BR(2) in Blake 40.1 (summer 2006): 39. 8. Alexander Gilchrist states that she left Linnell during the summer of 1828; see Life of William Blake, “Pictor Ignotus,” vol. 1 (London: Macmillan, 1863) 365. 9. According to Gilchrist 1: 367. 10. Including approximately 161 leaves of All Religions are One (see G. E. Bentley, Jr., Blake Books [Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1977] [hereafter BB] 82), at least one copy of the Descriptive Catalogue (BB 136), pl. 1 of The First Book of Urizen (BB 170), copies of For Children and For the Sexes (BB 192, 197), the manuscript of “For Children The Gates of Hell” (BB 215-16), Jerusalem copy E (BB 230), the manuscript Notebook (BB 334), “Pickering Manuscript” (BB 342), Poetical Sketches copies A, G, H, I, K, L, M, N, P, R, T, U, X (BB 346), Small Book of Designs copy B (BB 357), Songs of Innocence and of Experience copy W (BB 423), all of Blake’s surviving plates (BB 429), perhaps Tiriel B1 (BB 449), and Blake’s copies of The Tragedies of Aeschylus (1779) (BB 682) and Swedenborg, The Wisdom of Angels (BB 696). 11. BR(2) 459. 12. BR(2) 460. 13. BR(2) 467. 14. BR(2) 468. 15. See BR(2) 471. In a note to the artist and traveler Edward Thomas Daniell written shortly after 11 Sept. 1827, Linnell states, “Mrs Blake … lives with me now here [i.e., Cirencester Place].” George Cumberland addressed his letter dated 25 Nov. to “Mrs. Blake at Mr Linells 6 Cirencester Place” (BR[2] 477fn). However, Linnell spent most of his time at Hampstead with his family (see BR[2] 475). No record of Catherine’s having been invited to help Mrs. Linnell with the children at Hampstead has been traced. 16. In Nov. George Cumberland, Jr., called on Catherine at Cirencester Place; Linnell is not recorded as present. It appears that Catherine was responsible for persuading George Cumberland to buy the name plate and a copy of Job (see BR[2] 475, 479). After paying £5.15.6 for these works on 16 Jan. 1828, George Jr. reported to his father in Bristol that “[Catherine’s] late husbands works she intends to prin[t] with her own hands and trust to their sal[e] for a livelihood” (BR[2] 482). 17. In his letter to Catherine of 25 Nov., Cumberland explained that he could not sell the copy of Job in his possession. He also suggested a way of marketing the remainder of Blake’s works: That elaborate work, I have not only shewn to all our amateurs and artists here without success but am now pushing it through Clifton, by means of Mr Lane the Bookseller there, having previously placed it with Mr Tyson, Mr Trimlet, and another of our Print Sellers here without success—and as that is the case, and that even those who desired me to write to my friend for a List of his works and prices, (among whom were his great admirers from having seen what I possessed …) declined giving him any orders, on account, as they said, of the prices—I should not recommend you to send any more here—but rather to fix a place in London where all his works may be disposed of offering a complete set for Sale to the BMPR, as that will make them best known.—better even than their independant author who for his many virtues most deserved to be so—a Man who has stocked the english school with fine ideas,—above trick, fraud, or servility. (BR[2] 476) 18. BR(2) 477. 19. BR(2) 480. In his 1852 “Reminiscences” Robinson added, “[Catherine] informed us that she was going to live with Linnell as his housekeeper—And we understood that she would live with him. And he, as it were, to farm her Services and take all she had—” (BR[2] 705). As Bentley notes, “This sentence is not authorized by Robinson’s Diary or by the probable facts.” 20. BR(2) 484. For A Female Figure Crouching in a Cave, see Martin Butlin, The Paintings and Drawings of William Blake, 2 vols. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981) [hereafter Butlin] #134. 21. Gilchrist 1: 366. He is probably citing interviews with Tatham and possibly Linnell. However, Catherine’s manner of conducting business may sometimes have inhibited sales. Discussing his disagreement with Catherine and Tatham over the ownership of the Dante drawings and plates, Linnell observed on 16 Mar. 1831, “I cd. never obtain any definite account of what she expected or wished me to do” (BR[2] 541). She also appears to have exasperated Tatham (see BR[2] 493-94). 22. BR(2) 626. 23. BR(2) 490. On 19 Nov. Richmond wrote to Palmer, “Be pleased when you see Mrs B to present my best respects to her. I hope she is now settled” (BR[2] 491). 24. Quoted by G. E. Bentley, Jr., “William Blake and His Circle: A Checklist of Publications and Discoveries in 2007,” Blake 42.1 (summer 2008): 44. 25. BR(2) 493. 26. See Angus Whitehead, “‘I also beg Mr Blakes acceptance of my wearing apparel’: The Will of Henry Banes, Landlord of 3 Fountain Court, Strand, the Last Residence of William and Catherine Blake,” Blake 39.2 (fall 2005): 86-89. 27. BR(2) 495-96. In BR(2) the letter is dated 1 Apr. 1829. However, in answer to my querying this point, Bentley wrote, “The Frederick Tatham letter is clearly dated, in the MS copy (of which I have a reproduction), the only evidence of it, as 11 April 1829 (as in BRS [Blake Records Supplement (1988)]), not as 1 April (as in BR(2)) …” (personal correspondence, 25 Mar. 2005). 28. BR(2) 497. These included copies (probably later pulls) of the 1795 color prints Nebuchadnezzar, Pity, Newton, Christ Appearing to the Apostles after the Resurrection, God Judging Adam, and Satan Exulting over Eve (see BR[2] 871n39). 29. BR(2) 497-98. 30. See BR(2) 503-08. Catherine is compared in one review to the German poet Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock’s wife, Margareta (Meeta) Möller. On 27 Apr. 1830, after reading Cunningham’s life, the poet Caroline Bowles wrote to Robert Southey, “I hope she is not in indigence” (BR[2] 530). In early Mar. 1830 Linnell conducted Haviland Burke to Catherine’s residence to examine and purchase works for the Bishop of Limerick (BR[2] 509). Burke paid twenty guineas for “two Drawings” (the untraced Christ Showing the Print of Nails to the Disciples and The Body of Abel Found by Adam and Eve [Butlin #666], possibly a replica by Linnell of Blake’s painting of this name), prints of “Job” and “Ezekiel,” and a copy of Songs. 31. Gilchrist 1: 367. The copy of For the Sexes: The Gates of Paradise that Tatham gave Mr. Bird on the day of her funeral, 23 Oct. 1831, was probably from this collection (BR[2] 547). In his “Life of Blake” Tatham mentions that at her death Catherine had “writings, paintings, & a very great number of Copper Plates” (BR[2] 688). 32. See BR(2) 131, 151. 33. BR(2) 608. Smith also states that Catherine “became a draughtswoman … and has produced drawings.” According to Viscomi, “the significance of Blake printing his own plates and working with his wife cannot be overestimated” (Idea of the Book 105). If Catherine acted as Blake’s “printer’s devil,” as Viscomi suggests (Idea of the Book 117), or “clean hands,” as Essick describes her role (“Blake, Catherine Sophia,” ODNB), she would have been well versed in printing as well as coloring, but may have had less experience in carefully inking relief-etched copperplates. For the difficulties involved, see Michael Phillips, “The Printing of Blake’s America a Prophecy,” Print Quarterly 21.1 (2004): 18-38. On Catherine as printmaker, see Viscomi, Idea of the Book 393n4. 34. See BR(2) 790 and fn. For evidence of Catherine and Linnell’s printing of the Job plates on Blake’s press at Cirencester Place 1827-28, see BB 519. Catherine’s press work may have been inferior to Blake’s; Bentley notes “numerous minor defects” in her printing of Little Tom the Sailor (BB 578). 35. G. E. Bentley, Jr., The Stranger from Paradise: A Biography of William Blake (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001) [hereafter Stranger] 442. Posthumous copies of plates of Songs of Innocence and of Experience, poorly printed in light-blue ink, were on display at the Tate exhibition of Blake’s works at the Graves Art Gallery, Sheffield, May-Oct. 2003. Catherine may have printed plates of America (see BB 89), of Jerusalem copies H, I, J (BB 226-27), and of Songs of Innocence and of Experience copies a, b, c, d, f, g1, g2, i, j, k, l, o (BB 370-71). 36. Viscomi, Idea of the Book 367. 37. “Blake, Catherine Sophia,” ODNB; see also BR(2) 481fn and Butlin #829. Essick has raised the possibility that the colored copies of the Night Thoughts engravings may also have been colored by Catherine, c. 1797. “They clearly were not colored after a model, they vary in color placement in ways similar to the illuminated books colored up (according to Viscomi) in the same session, the palette slips and slides in tone but seems to be a matter of continuous color shifts rather than distinctly different palettes, the quality of the coloring varies greatly in the second half of many copies (she got tired?), and the colors are odd—the sort of things one sees in enamel decorations on British soft-paste porcelain of the eighteenth-century rather than colored prints in books (e.g., the Stedman, like the Night Thoughts published by a member of the Edwards family)” (e-mail, 7 Nov. 2005). It is possible that some of these copies could have been colored by Catherine after Blake’s death. 38. Butlin #C2. 39. Gilchrist 1: 70, quoted in Viscomi, Idea of the Book 129. 40. BR(2) 609. 41. BR(2) 690. Viscomi suggests that the following works were probably colored by Catherine, perhaps following a model by Blake: Innocence G and H, Songs C, R, AA, Experience R, America K, Marriage C, Europe A[?], Visions C, H, I, J, K, L, M (see Viscomi, Idea of the Book 133, 142). 42. At the same time, Linnell’s family moved from Collins’s Farm, Hampstead, to Porchester Terrace. Linnell was evidently in a poor state of health during this period due to overwork. This may have been another reason for Catherine’s move. 43. Quoted in BR(2) 690. It is unclear what Tatham is referring to by “such changes.” However, he is probably not alluding here to Catherine’s becoming “decayed” (a word he uses to describe her later in the “Life,” referred to by G. E. Bentley, Jr., Blake Records [Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1969] [hereafter BR] 567). Catherine’s letter to Lord Egremont suggests that she had personally delivered The Characters of Spenser’s “Faerie Queene” to Grosvenor Place several months after moving to her lodgings (see BR[2] 498). Grosvenor Place is some considerable distance southwest of Fitzroy Square. Whether she walked or took a carriage with the large panel on which Blake’s watercolor was mounted (Butlin #811 gives the dimensions as 18 x 53½ inches), such an errand is likely to have been beyond the capabilities of a frail woman. 44. See David Linnell, Blake, Palmer, Linnell and Co.: The Life of John Linnell (Lewes, Sussex: Book Guild, 1994) 86-87. 45. See, for example, BR(2) 482. 46. It appears that Linnell never actually paid Catherine for her housekeeping. In a letter to Tatham discussing their disagreement over the Dante watercolors and plates, he stipulates that before giving up the drawings he expects to be remunerated for the money he gave the Blakes but deducts twenty pounds for Mrs. Blake’s “taking Care of House &c in Cirencester Place” (BR[2] 539). However, as he never gave them up, it appears that Catherine never received the benefit of the “discount.” 47. BR(2) 690. 48. Blake, letter to William Hayley, 14 Jan. 1804 (The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake, ed. David V. Erdman [New York: Anchor–Random House, 1988] [hereafter E] 740). See also Angus Whitehead, “New Information Concerning Mrs Enoch, William and Catherine Blake’s ‘Fellow Inhabitant’ at 17 South Molton Street,” Notes and Queries 52.4 (2005): 460-63. 49. Lister 1: 13. 50. Gilchrist 1: 363. This detail originally appeared in Smith’s Nollekens and His Times: “Tatham, ill as he was, travelled ninety miles to attend the funeral of one for whom, next to his own family, he held the highest esteem” (quoted in BR[2] 626). He may have traveled from Shoreham. Richmond recalled a visit to Shoreham on 28 June 1827: “I asked my father’s permission to let me join my dear friends Samuel Palmer and Harry Waters and (I think) Fredk. Tatham, who were then in humble fashion lodging in the pretty village” (see A. M. W. Stirling, ed., The Richmond Papers: From the Correspondence and Manuscripts of George Richmond, R.A. and His Son Sir William Richmond R.A., K.C.B. [London: William Heinemann, 1926] 16). 51. Lister 1: 42. After a trip to London, Palmer wrote “Now for good news … Mr Tatham seems well!” (1: 44). 52. See D. Linnell 113-14. Thornton is almost certainly the physician and writer on botany Robert John Thornton, whose edition of Virgil’s Pastorals (1821) Blake illustrated with a series of woodcuts and whose Lord’s Prayer (1827) he annotated derisively (see BR[2] 376-77, 486; E 667-70). 53. BR(2) 690. 54. According to his grandson A. H. Palmer, Linnell’s favorite saying was “leave the dead to bury the dead” (Geoffrey Grigson, Samuel Palmer: The Visionary Years [London: Kegan Paul, 1947] 136). 55. BR 567 (Bentley gives the dates as “1828-1831?”); in Stranger 444 the dates are the same but Mrs. Tatham is not mentioned; BR(2) 754-55 refers to Catherine’s living with the Tathams from 1828 to spring 1829 (see note 7, above). 56. BR(2) 540, 552-53. In a letter which Bentley persuasively argues was written in 1833, Tatham writes from another address in Lisson Grove, 3 Grove Terrace (BR[2] 552). However, as I will demonstrate in a paper on Tatham currently in preparation, it is unlikely that he ever resided there. 57. BR(2) 691. 58. City of Westminster Archives Centre (hereafter COWAC), St. Marylebone rate books, vol. 55, 1828, part 2. 59. Pigot’s Directory (London: J. Pigot & Co., 1828) 351. The fact that the residence included shops suggests that it was a large property, expensive and spacious enough for studios for an aspiring sculptor. See The A to Z of Regency London [reprint of Richard Horwood, Map of London, 3rd ed., 1813], publication no. 131 (London: London Topographical Society, 1985) 1Ac. 60. COWAC, St. Marylebone rate books, vol. 56, 1829, part 1. 61. BR(2) 495-96. 62. The rate books for the period list Tatham Sr. as ratepayer for the property (see, for example, COWAC, St. Marylebone rate books, vol. 58, 1831). Linnell relates that “when I first knew [C. H. Tatham] he lived in a nice house that he had built one of the Alpha Cottages” (“Autobiography,” Fitzwilliam Museum Library, Cambridge, f. 42). Both C. H. Tatham and Linnell were members of the Keppel Street Baptist congregation (see BR[2] 68). Blake visited Alpha Cottages in 1825 (BR[2] 403). 63. Clayton’s Court Guide to the Environs of London, 1830 (London: Clayton, 1830) 214. The catalogue for the Royal Academy exhibition of 1830 records his address as 20 Lisson Grove (see Algernon Graves, The Royal Academy of Arts: A Complete Dictionary of Contributors and Their Work from Its Foundation in 1769 to 1904, vol. 7 [London: Henry Graves and Co. Ltd. and George Bell and Sons, 1906] 325). 64. COWAC, St. Marylebone rate books, vol. 58, 1830, part 1; Robson’s Directory (London: William Robson, 1830) n. pag. Some directories refer to the residence as 20a Lisson Grove North. However, this appears to be the same address previously occupied by William Eales: the rateable value, £45, is the same. 20 Lisson Grove itself, or the “Lodge,” which appears to have been a more recently built adjoining property, must have been grander, with a rateable value of £120. The ratepayer was the Rev. William Cockburn, dean of York and brother-in-law of Robert Peel (COWAC, St. Marylebone rate books, vol. 60, 1830, part 1). 65. COWAC, St. Marylebone rate books, vol. 60, 1831, part 1. Tatham is listed at “20a House & shops.” The 1831 census entry for 20 Lisson Grove records the presence of three males and two females (COWAC). 66. Robson’s Directory (1831) n. pag. Palmer bought a house nearby at 4 Grove Street, Lisson Grove, in 1832 (Lister 1: 83n1). 67. Linnell speaks of “many very interesting children all young at that time” (“Autobiography” f. 42); Palmer regularly refers to the Tatham sisters in his correspondence (see, for example, Grigson 42). Whether the eldest sisters Caroline (b. 1803) and Lydia (b. 1807) were still living at home at this date is unclear. In the spring of 1828 Frederick’s brother and fellow Ancient, Arthur, was approaching the end of his first year at Magdalene College, Cambridge. 68. Gilchrist 1: 365. 69. See BR(2) 495. 70. Society of Arts, Transactions vol. 42 (1824-25) xlvi. Information kindly supplied by Nicola Gray, archivist and records manager, Royal Society of Arts. 71. See Jane Johnson, ed., Works Exhibited at the Royal Society of British Artists, 1824-1893 (Woodbridge: Antique Collectors’ Club, 1975) 452, and “Fine Arts. Suffolk Street Gallery. The Sculpture Room,” London Literary Gazette; and Journal of Belles Lettres, Arts, Sciences (2 May 1829): 289. 72. Frederick Tatham, painter, of “1, Queen Street, Mayfair,” exhibited two portraits at the Royal Academy of Arts exhibition in 1825 (see Graves 7: 325). 73. C. H. Tatham gives Queen Street as his address in the Royal Academy exhibition catalogues for 1809 to 1831 (see Graves 7: 324-25). 74. Quoted in D. Linnell 113. In the same letter, Tatham states that “my poor afflicted son [Frederick] is pulled back and back; the subject is worn out with me. I wish I could get him abroad; but my hands are tied and bound—my large family and my decreasing occupations threaten straitened circumstances. I am the milch cow to fifteen living souls—think of that, Johnny!” (see Alfred T. Story, The Life of John Linnell, vol. 1 [London: Richard Bentley and Son, 1892] 153). 75. D. Linnell 88. The first of May fell on a Monday in 1820 and 1826; 1820 seems unlikely because Frederick would have been about fourteen, slightly young for the independence his father describes. 76. It is unclear whether her duties were merely to attend to Frederick and his chambers or to act as housekeeper for the whole premises, including the offices of C. H. Tatham’s practice as an architect. 77. See BR(2) 83-84. 78. G. E. Bentley, Jr., Blake Records Supplement (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988) [hereafter BRS] 128. 79. BR(2) 397. 80. Linnell, “Autobiography” f. 45. 81. BR(2) 398. Catherine’s letter to the Earl of Egremont (Aug. 1829) is also signed “C Blake” (BR[2] 498). 82. BR 288-89n4. 83. E 782-83. C. H. Tatham’s name features in Linnell’s Job accounts for 29 Apr. 1826, which suggests that Tatham and Blake may have met in 1826 (see BR[2] 800). 84. “An alternative date for the gift is 1827-31, when Catherine Blake was living as a widow with C. H. Tatham’s son Frederick” (BR[2] 398fn); “It seems improbable … that a gift from Blake to Tatham would bear a note from Mrs. Blake; it is more probable that the impression was a gift from Mrs. Blake sometime between Blake’s death on 12 August 1827 and her own death on 18 October 1831” (Robert N. Essick, The Separate Plates of William Blake: A Catalogue [Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1983] 189). 85. As Tatham Sr. is recorded as residing at or working from 1 Queen Street from 1809 (see note 73, above), Catherine may previously have had occasion to visit the premises. 86. This context may throw light upon the inscription, a quotation from Lavater’s Aphorisms which William Blake underlined in his copy (see BR[2] 398fn). 87. BR 567. The entry in BR(2) reads “Catherine Blake, according to Tatham, ‘resided for some time’ … at 20 Lisson Grove with the Tathams” (755). 88. Quoted in BR(2) 690. 89. BR(2) 546. Tatham’s language here was probably influenced by the preaching of his Newman Street Catholic Apostolic Church minister, Edward Irving (see my paper on Tatham, currently in preparation). 90. Gilchrist 1: 367. 91. Henry Curtis, “Frederick Tatham’s Wife,” Notes and Queries vol. 153 (2 July 1927): 9. 92. BR(2) 936. 93. A transcription of the entry in the marriage register reads: “Marriages solemnized in the Parish of St Mary Stratford, Bow, in the County of Middlesex in the Year 1831. Frederick Tatham, of this Parish, Bachelor, and Louisa Keen Viney, of this Parish, Spinster, were married in this Church by banns this Twenty Fifth Day of April in the Year One Thousand Eight Hundred and Thirty One By me John Stock. This Marriage was solemnized between us: Frederick Tatham, Louisa Keen Viney. In the presence of: Henry Brooke Marriott, James Harris” (p. 179, no. 27). A scan can be accessed at the Tatham Family History web site, <http://www.saxonlodge.net/showmedia.php?mediaID=109&medialinkID=155>. 94. PRO PROB 11/1751, quoted in Whitehead, ‘“I also beg Mr Blakes acceptance’” 83. 95. Sarah Banes, Catherine’s sister and Banes’s wife, had been the sole executrix of his earlier will. However, she had died in Mar. 1824 (see Whitehead, ‘“I also beg Mr Blakes acceptance’” 83). 96. BR(2) 501. 97. BR(2) 499. 98. BR(2) 501-02. 99. See Joseph Hogarth’s account, quoted in BR(2) 493-94. 100. Stranger 492n14. 101. According to Hogarth, Tatham “left [Catherine]. Early the following morning she called upon [Tatham] …” (BR[2] 494). This suggests that they were living apart when the incident took place. However, for Catherine to have called upon Tatham during this period would have meant an early morning walk north from Fitzroy Square to Lisson Grove North or possibly Alpha Road. 102. “Life of Blake,” quoted in BR(2) 690. 103. Her stay with Linnell is also not mentioned in Tatham’s letter of 11 Apr. 1829 (BR[2] 495-96). This may suggest that disagreements between Linnell and Catherine and Tatham had occurred as early as Apr. 1829. However, he may merely have wished to avoid a detailed description of her movements since leaving Fountain Court. Note that Tatham also omits any reference in the letter to Catherine’s period of residence with him. 104. BR(2) 754-55; see also Wilson 366. 105. In introductory remarks to his transcription of the “Life of Blake,” Bentley says, “Tatham is not very trustworthy, but it is probably best to trust him until we have cause not to” (BR[2] 662). 106. See BR(2) 551-60. Tatham claimed, with no corroborating evidence, that Catherine “bequeathed her all” to him and his wife (“Life of Blake,” quoted in BR[2] 690). 107. D. Linnell 116. 108. Robson’s Directory (London: William Robson, 1836) 434; E 783. Maria Denman and Mary Ann Flaxman, Flaxman’s sister, were co-executrices and co-inheritors of his estate (see will of John Flaxman, PRO PROB 11/1720 [proved 17 Jan. 1827]). Both appear to have lived at Buckingham Street. Blake met them at the Aders’s party on 10 Dec. 1825 (BR[2] 419). 109. See Mary Lynn Johnson, “More on Blake’s (and Bentley’s) ‘White Collar Maecenas,’” Blake in Our Time, ed. Karen Mulhallen (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010) 150. 110. See BR(2) 460-61. 111. BR(2) 691. 112. See Graves 2: 333 (under Dinham). At the 1830 Royal Academy exhibition, Dinham exhibited a “bust of a daughter of C. H. Tatham, Esq.,” and in 1844 a “bust in marble of Mrs. Richmond.” Grigson (144n3) states that Dinham’s “bust of George Richmond is in the National Portrait Gallery, and he exhibited a ‘colossal bust’ of Frederick Tatham at the Society of British Artists in 1830.” He suggests that Dinham and Bird, another artist who attended Catherine’s funeral, were Ancients: “They were on its fringe, at any rate.” 113. Graves 1: 200. Tatham’s friendship with this Devonshire artist may be associated with his brother Arthur’s ordination as rector of Boconnoc with Bradoc (Broadoak), Cornwall, at Exeter Cathedral in 1832. 114. Gilchrist 1: 365. The index to The A to Z of Regency London does not include an Upper Charlotte Street. 115. See Arthur Symons, William Blake (London: Jonathan Cape, 1940) 238; Wilson 366; Thomas Wright, The Life of William Blake, vol. 2 (Olney: Thomas Wright, 1929) 121; Jack Lindsay, William Blake: His Life and Work (London: Constable, 1978) 269; James King, William Blake: His Life (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1991) 229. 116. BR 567. 117. BRS xlviii; Stranger 444. 118. Peter Ackroyd, Blake (London: Sinclair-Stevenson, 1995) 368; Essick, “Blake, Catherine Sophia,” ODNB. This address is also given by Michael Davis, William Blake: A New Kind of Man (London: Paul Elek, 1977) 163. 119. BR(2) 754. 120. BR(2) 754fn. 121. BR(2) 498. 122. BR(2) 546-47. 123. Butlin p. 625. Bentley gives the address correctly in a footnote in BRS (92n2) but refers to “Charlton Street” elsewhere (xlviii). 124. The original letter has not been traced. It was transcribed by Thomas Hartley Cromek, son of Blake’s former employer Robert Cromek, in his manuscript “Recollections of Conversations with Mr. John Pye” (1865) 56-58 (see BR[2] 871n37). 125. For Children copy C; see BB 192. Cumberland probably purchased this copy from Catherine while she lived in these lodgings. 126. BR(2) 755fn. Bentley’s source at the St. Marylebone Public Library appears to have checked only the rate book entries for Charlton Street and not those for Upper Charlton Street. 127. Pigot’s Directory, 1829, n. pag. 128. Rate book entry, 17 Upper Charlton Street, Fitzroy Square, 1829 (COWAC). 129. Pigot’s Directory, 1839, 70. 130. The house was at the northern end of the east side of the street, almost on the corner of Carburton Street. Catherine appears to have resided between a tailor, E. Griffiths, at no. 16 and a small public house, the Lord Nelson or Nelson’s Head, at no. 18, run by Edward Hughes 1828-30 and William James Barnard from 1831. Other businesspeople in the street included a cabinetmaker, painter, pianoforte maker, leather gilder, chairmaker, stonemason, furniture maker, and five tailors. 131. Linnell, “Autobiography,” f. 33. Elsewhere he writes, “indeed I feel bound to say that I owe more to [Mulready] than anyone I ever knew” (f. 9). In the “Autobiography” there are far more references to Mulready than to Blake or Varley. It is clear that, at the time of writing, Linnell regarded Mulready as the greatest influence. 132. Linnell, “Autobiography,” ff. 31, 33. 133. Graves 5: 323. 134. Rate book entry for 17 Upper Charlton Street, Fitzroy Square, 1830 (COWAC). 135. It is unclear whether she lived above the baker’s establishment or at the back of the shop. In 1832 Ann and Edward Maddle, ratepayers at 14 Upper Charlton Street, had a female lodger, Elizabeth Tuckwell, staying in their back kitchen (see The Proceedings of the Old Bailey, 1674-1913, <http://www.oldbaileyonline.org>, t18320906-361). However, in Catherine’s case this seems unlikely. 136. See Whitehead, “William Blake’s Last Residence: No. 3 Fountain Court, Strand. George Richmond’s Plan and an Unrecorded Letter to John Linnell,” British Art Journal 6.1 (2005): 21-30, and “‘I write in South Molton Street, what I both see and hear’: Reconstructing William and Catherine Blake’s Residence and Studio at 17 South Molton Street, Oxford Street,” British Art Journal 11.2 (2010): 62-75. 137. Whether by early 1829 Catherine still possessed her husband’s press, had replaced it with a smaller one (see BR[2] 467-68), or had no press, has yet to be established conclusively. 138. Perhaps her great-nephews Richard and Thomas Best assisted her (see Whitehead, ‘“I also beg Mr Blakes acceptance’” 91n85). Catherine would probably not have had continuous access to the space needed to operate a rolling press at her two former homes. However, during her years at 17 Upper Charlton Street, the front room would have provided a permanent location for printing sessions. 139. See Gilchrist 1: 246. 140. Essick, “Blake, Catherine Sophia,” ODNB. 141. Mark Crosby and Robert N. Essick, “‘the fiends of Commerce’: Blake’s Letter to William Hayley, 7 August 1804,” Blake 44.2 (fall 2010): 72. |