note

begin page 190 | ↑ back to topThe Meaning of Mirth and Her Companions in Blake’s Designs for L’Allegro and Il Penseroso. Part II: Of Some Remarks Made and Designs Discussed at the MLA Seminar 12: “Illuminated Books by William Blake,” 29 December 1970

“The wisest of the Ancients considerd what is not too Explicit as the fittest for Instruction because it rouzes the faculties to act.”

Blake, letter to Trusler, 23 August 1799 (E 676/K 793)

Blake is certainly not above criticism, but his work will not just lie there, like an inert legacy, passively waiting to be explained—or exploited. Blake was exasperated with Trusler because the Reverend had declared Blake in need of someone else “to elucidate” his ideas. In all his work both as poet and painter Blake was constantly striving to do exactly that for himself. To his disciples Blake was “The Interpreter”—of life as well as other men’s works; to scholars Blake is also the interpreter of his own work, not the only one, but the primary one. How is it then, that there has been much erroneous or irrelevant criticism of Blake? Ignorance of the range of Blake’s symbolism seems to be the root cause of most misinterpretations. Or, what comes to the same thing, exegetes have not tried hard enough to ascertain Blake’s own opinions.

At times hostile critics take issue with Blake because they disagree with him or even find his thought objectionable. This is fair enough, if Blake has been correctly construed; every thinker has to take his chances. What is impermissible is to misrepresent Blake’s ideas while professing to expound them. Now that Damon’s Blake Dictionary is available in paperback (oddly in the 1965 rather than the 1967 version), even the Blakist of modest means has only to complete the easy additional task of checking out the key terms at issue in the Erdman Concordance in order to get straight about most problems verbal. The authorial impulse involved in the next stage, that of putting the resulting thoughts down on paper, must still be reckoned with, but the desire to write need not be at odds with Blakean actualities. No guide to the pictorial aspect of Blake’s work is as convenient as the Concordance, but a number of important publications in 1971 have helped to make his art more locatable and accessible. Especially noteworthy are Essick’s updated Finding List in the Summer-Fall 1971 issue of the Blake Newsletter and the catalogues of the Thorne collection by Bentley, of the Fitzwilliam collection by Bindman, and the Tate collection, revised, by Butlin. One must also mention Keynes’s Blake Trust facsimile of THERE is NO Natural Religion and his catalogue of the Gray designs, which is complemented by Tayler’s outstanding interpretive edition. Finally, though it does not constitute an ideal instrument for reference, the purportedly complete (as corrected) Micro Methods filmstrip of the Night Thoughts designs ought also to be consulted by a scholar before he makes a pronouncement on a pictorial problem. Blake’s largest begin page 191 | ↑ back to top gallery of pictorial imagery can no longer be disregarded because an earlier generation of scholars saw fit to denigrate these great designs as works of art. After having made all the necessary checks, however, the true scholar must still decide whether what he has to say represents a substantial addition to what is known or, at least, a significant correction or clarification of the issues. It is not a sufficient justification that one say something new. It is not even sufficient that one say something true.

The additions of Songs of Experience to Songs of Innocence, together with the other alterations made in forming the consolidated anthology, stand as examples of how Blake continued to draw on the stock of verbal and visual images established in his earlier work. This aspect of his art is particularly interesting for our purposes since Damon has proposed that Blake derived his idea for an amalgamated Songs from Milton’s example in the twin-poem L’Allegro-Il Penseroso. But in returning to an image, Blake rarely repeats himself exactly. Usually an image is re-employed only with noteworthy variations which may, in turn, alter the valuation radically, as from positive to negative or vice versa, or at least qualify it appreciably. Recent criticism has tended to employ the term “irony” to describe this strategy of variation. But once the suspicion of irony has been raised, everything, especially everything ostensibly positive, seems called into doubt, and what Swift referred to as “the converting imagination” is liable to take command of critical vision. Few of those familiar with the literature have not felt that Blake has on occasion been made to appear oblique where he himself strove successfully to be direct. The possibility of irony must somehow be tested to determine its presence though I have no infallible test to propose. All I would urge is that the expositor ask not whether he is able to construe the image in question ironically, but whether Blake gives him sufficient authorization for attempting to do so.

What I do want to insist, however, is that Blake’s capacity for irony seems to have been a gift more than a development. The record hardly allows us to imagine a time before which Blake was incapable of irony and one of the few indubitable things Blake must have found valid in Platonism is Socratic irony. Since as a critic I myself have sometimes been linked with the school of irony, I can hardly suppose irony to be a wholly unprofitable interpretive concern. Nevertheless, we can still profit from a modest denial Northrop Frye made during the bicentennial year, well before there had been much talk about Blake’s irony: Frye went so far as to declare that Blake’s writing lacks irony (Fables of Identity, p. 139). Had more consideration been given to this dictum, I believe that scholarship would have been spared much ingenious but unprofitable commentary.

It remains true, however, that one essential aspect of Blake’s art necessarily involves something very like irony. Even more than other great artists Blake was attracted to such strategies as counterparts, sequels, contraries, and alternative versions; moreover, his deployment of several media simultaneously seems to have generated juxtapositions that can only be understood as ironical in some sense. The most notorious case is that of “The Tyger,” where the sublime terror of the poem is set against a picture of the beast that is—usually—unheroic, if not contemptible. I have written at length about this problem elsewhere and do not wish to reiterate here. But I continue to maintain that the incommensurability of the picture and the poem is too patent to have been accidental and that only prejudice has led viewers to suppose that a picture which accompanies a poem must illustrate it, in the sense, that is, of attempting to imitate its mood and angle of vision. Beneath this prejudice seems to lurk the superstition about appearance and reality that the truest image of a tiger is a bloodthirsty ferocious beast, such as was sighted for a time in the drafts of the poem. If, on the contrary, one looks at actual tigers in a zoo, or even at Stubbs’s pictures of tigers, he will be led to reflect how much the savage abstraction is a projection of his own fears and fantasies, as well as those of his culture. Like the Ghost of a Flea, an image of a terrifying tiger is a phantom in the theatre of selfhood.

I remain convinced, therefore, that Blake wanted us to understand all this as an implication of the indubitable non-correspondence between his picture and text in the same plate. It does not, of course, follow that all or most of his other pictures stand in such an antithetical or “ironic” relation to a text. Indeed, such discrepancies seem to be quite rare, and to have been aimed chiefly at rousing the spectator’s faculties to act in a more imaginative or inquiring manner than they do when he is content to look at pictures as illustrations merely. Whether the technique of non-correspondence is best referred to as “illumination,” as Hagstrum seems to have proposed, is another matter. Whatever we should call it, we cannot doubt that, as a multi-media artist, Blake always has a palpable design on the viewer; Blake is trying to elicit or provoke a determinate response from his audience, rather than incoherent evidence that they have been moved. Still, I suppose he would have been gratified to know that anybody had bothered to memorize one of his poems, much less pour over his pictures, or even make a glad noise to accompany meditations stimulated by one or the other. No doubt I’m referring to Ginsberg and Orlovsky here.

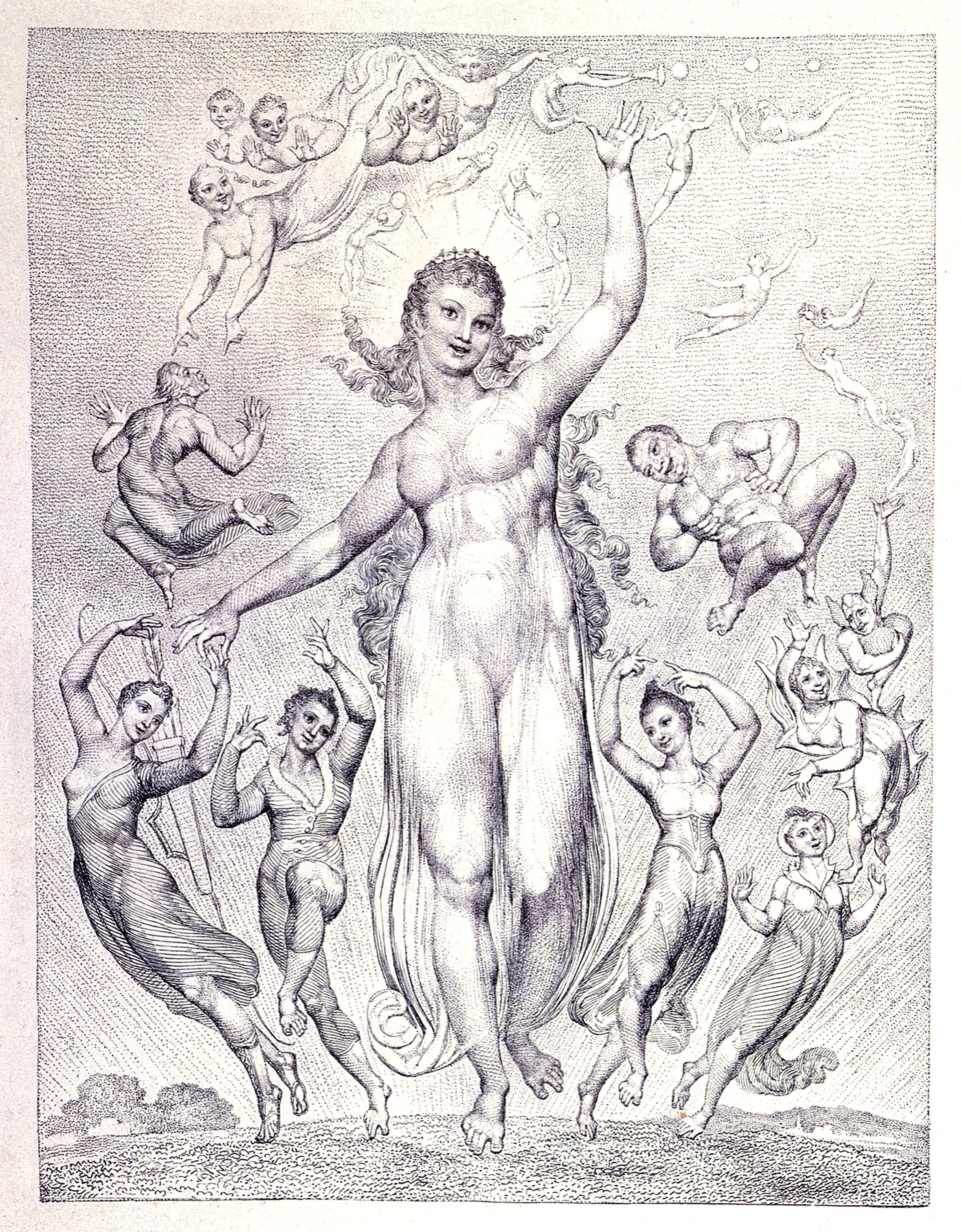

The first task for an interpreter is to see a poem or picture as it is. I tried to give an adequate descriptive account of the initial design for L’Allegro in the first part of this discussion (Blake Newsletter 16, 4 [Spring 1971], 117-34). Now I wish to begin an interpretation by propounding the captious question: “What is the matter with Mirth?”

I will quickly add that this would be a bad question for a class of beginning students since it might encourage them not to get to the first base in Blake studies, which is the ability to distinguish between Innocence and Experience. Confusion at this level is both natural and lamentable. The first premise for a balanced presentation should be “Mirth is a good thing, and don’t you forget it!” begin page 192 | ↑ back to top

Of course, being mostly readers, we tend to place more faith in words than in pictures and are likely to be put in a more receptive mood by some more words. Here are a few relevant things Blake said when he was laying it on the line:

Early (Ann. Lavater, E 574/K 67): “I hate scarce smiles I love laughing.”

Later (to Trusler, 23 August 1799, E 676/K 793): “Fun I love, but too much Fun is of all things the most loathsome. Mirth is better than Fun & Happiness is better than Mirth—I feel that a Man may be happy in This World. And I know that This World Is a World of Imagination & Vision.”

I most want to call attention to the display of Blake’s mental powers of discrimination in this passage, his insistance on qualification, even when he was out of all patience in dealing with a fool. The placing of “Mirth” in a middle position with respect to value is also a point to reflect upon, though, in itself, it is not a more decisive consideration than that nice little pencil drawing of “Mirth” that Keynes reproduces as plate 19 in his 1956 selection of drawings. If this be irony, let us make the most of it.

What are all those golden builders up to anyway? Are there destroyers among them?

There is probably a conventional element in Blake’s designs for L’Allegro and Il Penseroso that would have been apparent to his contemporaries who were familiar with the stage and pictorial traditions representing these subjects. More closely connected with Blake’s designs in some respects than any of the helpful pictures reproduced in Marcia Pointon’s Milton and English Art are two designs by George Romney, “Mrs. Jordan as L’Allegro” and “Mrs. Yates as Melancholy,” which I have seen only briefly in large engravings by R. Dunkerton dated 1 October 1771. My notes indicate that begin page 193 | ↑ back to top

There is only one musical instrument depicted in the watercolor version of Mirth and her Companions, the long trumpet being blown by the little twisting figure who takes off in slightly differing ways, described in Part I, from the left hand of Mirth in Blake’s two earlier versions of the design. I should say that I have considered the possibility that the relation of the trumpeter to Mirth’s hand may be coincidental, as is perhaps the case with the relation of Quiet to the hand of Melancholy in design 7, but this seems to me a dubious hypothesis; Blake deliberately placed the hands in various positions and all must be accounted for. To think at all about this problem, of course, we must consider why Blake relocated the left forearm of Mirth in the second state of the engraving [figs. 1 and 2] and this positioning, I suspect, leads us back to the general question of meaning, the problem of what, if anything, is wrong with Mirth. But I am not ready to consider the overall meaning of the picture just yet.

First, it is noteworthy that there are three balls or bubbles to the right of the trumpet which nobody would doubt have been blown from the horn. I can think of no other example in Blake’s work of bubbles being blown from a horn, though any Blakist would suspect that such symbolism implies an unfavorable comment. It is true that bubbles may well be portentous, as the transparent spheres certainly are in the painting “The Fall of Man” [fig. 3], which I mentioned in Part I in connection with design 6, but their conventional associations with trivial or unworthy goals are also utilized; thus Blake represents them in Night Thoughts no. 39 (II, 5), but they may be soporific or distracting, as with Fame’s Trumpet, Night Thoughts no. 352 (VIII, begin page 194 | ↑ back to top

begin page 195 | ↑ back to top 6). Blake must have thought this trumpet was celebrating folly, but the great trumpet blowing in “The Five Wise and the Five Foolish Virgins” (no. 44 in Butlin’s revised Tate Gallery catalogue: this version is now supposed to be a copy) resounds to clarify the definitions of both parties. Perhaps the trumpet in Mirth can also make a discriminating sound, even though it issues bubbles of vain vision.Before we consider the activities of the other figures, it is well to identify them as definitely as we can, still bearing in mind Blake’s declaration that “all” Milton’s personifications are represented in this picture. Sport, Wrinkled Care, and Laughter are all labelled in the second state of the engraving [fig. 2], and there is no doubt that the central figure is Mirth, whatever else one might feel compelled to call her. The “Mountain Nymph Sweet Liberty” is likewise unmistakable. (Perhaps Blake’s image of her was further particularized in response to lines 70-72 in Collins’s “The Passions: An Ode for Music”: “When Cheerfulness, a Nymph of healthiest Hue, / Her Bow a-cross her Shoulder flung, / Her Buskins gem’d with Morning Dew. . . .”) It seems reasonable to agree with Keynes that the boy who attends Mirth is Jest while the girl beside her is Youthful Jollity. This leaves the girl at the right in the front five unidentified and the various other subordinate figures to be connected with the six abstractions mentioned in lines 27 and 28 of the poem. Morton Paley suggested that there may be implications now lost to us in some of the archaic words, but the annotations in standard students’ editions of Milton do not indicate anything decisive. Because neither Blake’s nor Milton’s words seem to imply a different order of correspondence, it seems best to read down the picture for personifications in line 27. Thus, the trumpeter and the two or more people beneath his bubbles are Quips; the flyer and his companions—there are definitely three in the engraved versions—are Cranks (i.e., witticisms); and the girl at the front right, the bat-winged female above her and the ass-eared creature above her are Wanton Wiles. Rather whimsically I call the girl “Kitty” because of her cat whiskers in the engraved version—a detail brought to my attention some years ago by Irene Tayler—the woman above her consequently being “Batty” and the male creature above her “Assy.” This makes Nods the two women to the left of Sport, Becks the two women to her right (the second of these with outspread arms, trimmed in the watercolor, in the position of a presiding or sponsoring spirit), and Wreathed Smiles being the four or more spirits in the halo of Mirth. The fact that Smiles spirits definitely become musicians, with two horns and two tambourines, in the engraved versions is a distinct indication to me that, in the end, Blake arrived at a less negative attitude towards the whole group, though I cautioned earlier against being too sanguine about Blakean music.

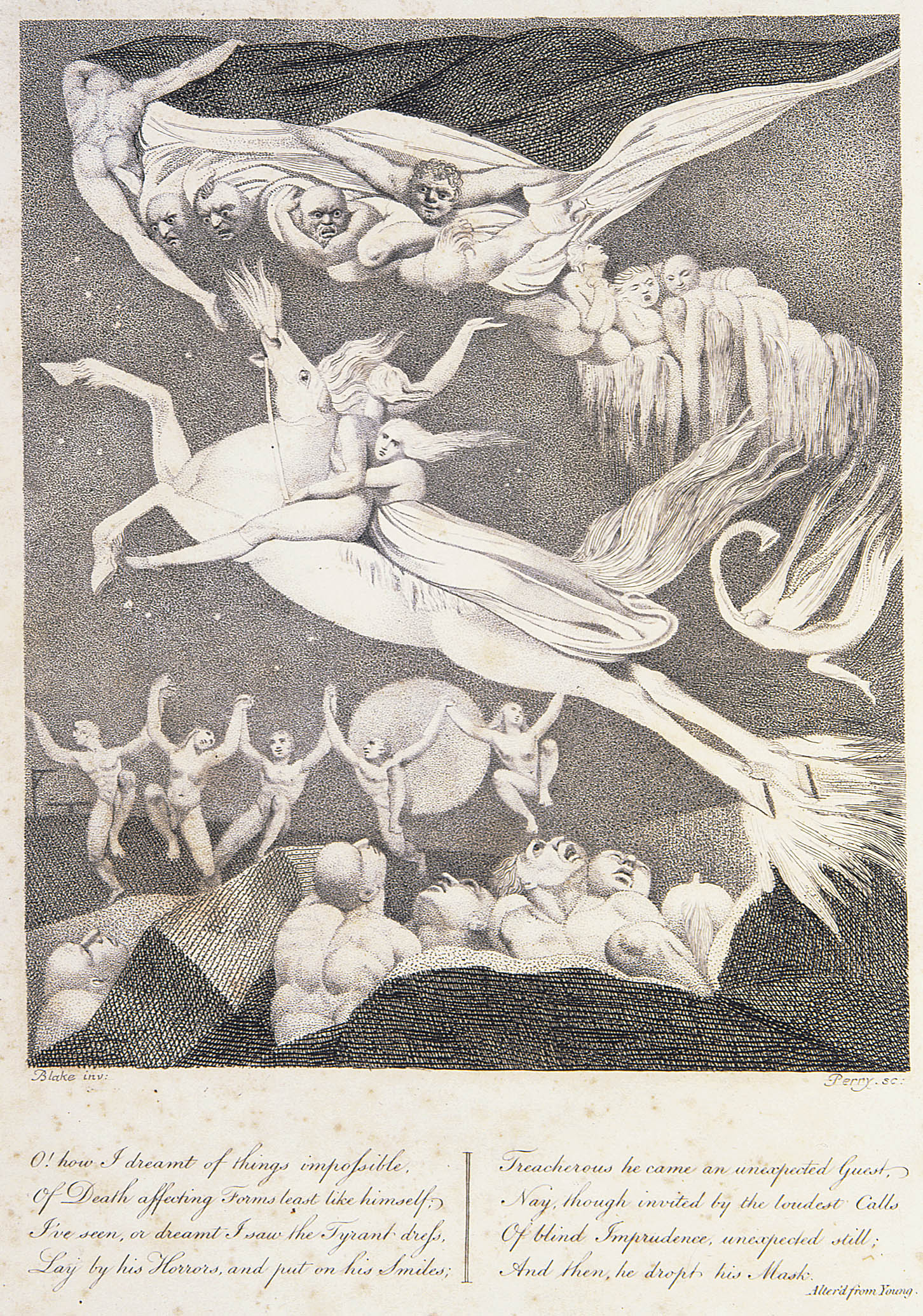

Pictures that Blake made later in his career are often most clearly understood as transformations of pictures he made earlier, with important elements having been added or subtracted; such systematic counterparting produces works that tend to exist in an Innocence-Experience relationship. I have already in effect cautioned against trying to see the relationship between designs 1 and 7 as a simple contrast between Innocence and Experience. The visions in the two designs can be more precisely described as, first, a quasi- (not pseudo-) Innocence and, second, a qualified (incompletely organized) Experience. It is not to be expected that either state will be found pure in this world. In certain respects “Mirth and her Companions” stands in a more distinctly contrary relationship to Blake’s frontispiece for J. T. Stanley’s version of G. A. Bürger’s Lenore [fig. 4], which was designed twenty years earlier and may be understood as a negative prototype to the L’Allegro design. The symbolic continuities are remarkable; for example, the front five of Mirth are quite similar, at times even in posture, to the five dancers in the middle distance between the moon and gibbet in the background and the grave in the foreground (which is closely related to the titlepage of Vala) in the Leonora frontispiece. There is also a trumpeter in the Bürger design, though he has a more serpentine instrument and is differently positioned than the one in Mirth. The commanding pall of Death at the top of the Bürger design, which Blake used again in Night Thoughts no. 81 (III, 6) [fig. 5] is related to that of Night in Il Penseroso 7 and elsewhere, but it is the Fiery Cherub Contemplation who dominates the Milton design and assures that Melancholy and her Companions have the capacity to see as far as Job and his companions in Job 14. The second Beck, who tries to exercise comparable control, is a rather shadowy figure in the watercolor version of Mirth, but she comes through more clearly as a Mirth-dispenser in the engravings. Is she not the airy sister of lady Ololon who spreads her blessings over the human harvest on the last plate of Milton?

But the smiling face shown by Death in the Leonora frontispiece continues to haunt us. It bears a close resemblance to the beefy face of Laughter, especially as he is represented in the engraved versions. Though it is appreciably heavier, the face of Death is also similar to the sober face of Satan in His Original Glory (no. 33 in Butlin’s revised Tate Gallery catalogue). And both faces also have a distinct resemblance to that of Jest who dances at the right side of Mirth—not as he is represented in the watercolor but in both engraved versions; even noteworthy is the fact that the hair-crown complex of Satan comes to a point, quite like the hair of Jest. I do not believe that Blake meant us to infer from this that Jest is lethal, but perhaps he would have his fans recall the simple-seeming “Blind-man’s Buff” and the affinity between “The laughing jest, the love-sick tale” (E 413/K 16).

Perhaps the moral of these family resemblances in L’Allegro 1 is that the particular likeness of Laughter to Death is reason enough to suspect laughing, and the proximity of Laughter to Assy is another good reason to be dubious about its consequences. Laughter may be lovable, but it must not be allowed to dominate, as Hobbes and others have supposed it inclined by nature to do. Laughter is doubtless most jolly when holding himself to his own place. In the case of Jest, however, his resemblance is closer to the pre-lapsarian Satan than to the postlapsarian Death; if the interpreter were to argue that Jest’s high-stepping is to be understood merely begin page 196 | ↑ back to top

The two chief figures in the Leonora frontispiece, the hero and heroine boldly setting out above the moon on a fiery horse, did not survive this seeming-brave beginning as the ballad makes clear, and if they are to return at all in the company of Mirth they will have to get over some unfortunate habits, an accomplishment not impossible, as suggested by the resurrection of the Youth and the Virgin in “Ah! Sun-Flower.” Unquestionably they have a weakness for reckless driving and a too-familiar relationship with Death. Like the male rider in the background of the colorprint “Pity” (no. 19 in Butlin’s revised Tate Gallery catalogue) the hero does not show his face, but if he did, the poem suggests, he might himself look like Death on a Pale Horse, in that other equestrian picture now in the Fitzwilliam collection (in Bindman’s catalogue).

Faces thus deliberately turned away from the viewer, it must be said, are particularly challenging for the interpreter. I believe that the figure at eleven o’clock in the Leonora design, who manages to cling to the pall of Death and tries also to hold onto his head, is the hero just escaped to this next ambush of Death; he is much like the similarly depicted man at two o’clock in Europe 2. The real face of such figures may be either what we suppose that of the scribe to be in “God Writing on the Tables of the Covenant” (Figgis, pl. 55) or Jesus in “The Ascension” (Graham-Robertson, pl. 33—now Fitzwilliam, no. 23), but the wind that blows the hair of Bürger’s hero associates him with the former. The possibility of a redeeming face ought never to be foreclosed, however; in Blake’s symbolism the problematic figure of “furious desires” in Urizen 3 (no. 13 in Butlin’s revised Tate Gallery catalogue) becomes the Holy Spirit that dominates the Genesis titlepage (see Damon, Dictionary, pl. II) or the central figure of the Redeemer in “The River of Life” (no. 19 in Butlin’s revised Tate Gallery catalogue). When something of his face is revealed, he appears as Milton about to descend to Eternal Death in the titlepage of Milton or as some of the many faces of Jesus.

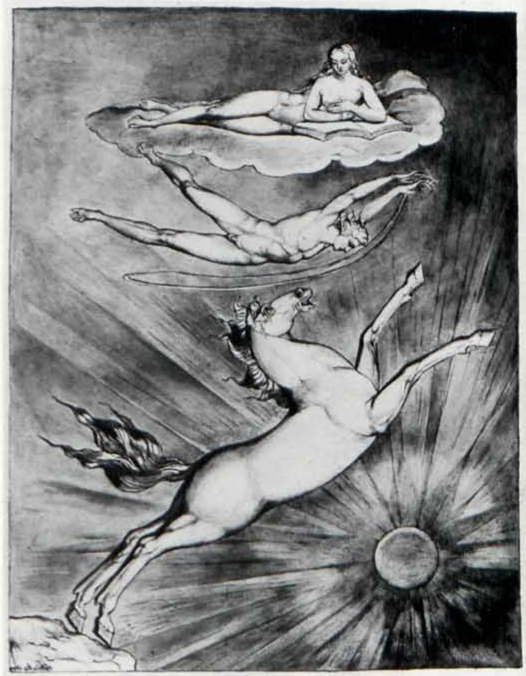

The missing link in this symbolism of regeneration is the great design of a “Spirit with Fiery Pegasus” [fig. 6], no. VI in the Descriptive Catalogue (E 536/K 581). There we see that, of its own accord, this Eternal Horse (magnified from MHH 27) is leaping from the barren cliffs over the very sun as it is about to be bridled by a rider who shows his face and knows how much spirit great Pegasus possesses without dependency on external wings. The girl on the cloud, who is both a sister to regenerate Earth as depicted in L’Allegro 2 and a

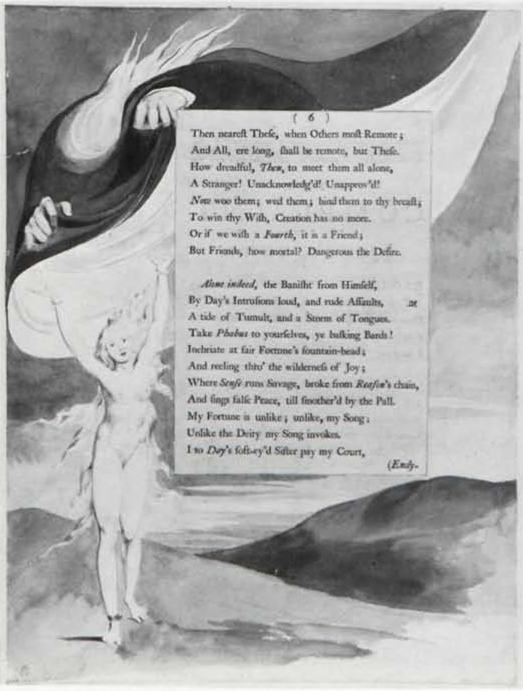

begin page 198 | ↑ back to top front view of resurrected Earth as depicted in the “Introduction” to Experience, is shown learning all that is involved in transport, both from the reality of her cloud and the wisdom of her book.The interesting inscription on the Leonora frontispiece, which is altered from Young’s Night Thoughts, also leads us to a pair of Blake designs that accompany the actual lines of Young’s poem. These are, first, a pretty girl with wonderful red hair who sits on an odd leafy stump while clutching a bow and arrow, Night Thoughts no. 203 (V, 48; cf. Vala p. 124) [fig. 7]. The sequel, no. 204 (V, 49) [fig. 8] shows the other side of hypocrite Death (with a long cue of hair) being observed by the adventuring traveller from behind, as he leans on a mound while still holding his bow and flaunting his pretty girl mask. The next design, no. 205 (V, 50) [fig. 9] shows Death as a huge reveller with a crown of roses reaching down and holding hands with two humans who are dancing thoughtlessly to the tune of two human musicians and being inspired by the spirits of the punch bowl. I am sorry to be prompted by such closely connected pictures to further suspicions concerning the ethical status of Mirth and her Companions. I too love laughing and, like everyone else, would be happier if we could dispense with irony.

When it comes back to Mirth and Melancholy, which is better? Which is Good? Or should we perhaps

try to get beyond Good and Evil altogether? Let us get inside good and evil, rather. Jerusalem has as one of its themes a concern I have never seen adequately discussed in print—except, of course, by Blake. Briefly, it is how to distinguish what is valid in Jerusalem and what is valid in Vala. The problem is attractively enough presented in J 32 (46)—note the spirit urging a girl to rise and compare the plight of Kitty—but the sequel sometimes is J 47, where the two women are shown to have turned Albion’s head and confounded him. This difficulty is unresolved as it is reenacted by Cambel and Gwendolyn in J 81, but possibly resolved for each woman in J 96 and J 99. In “The Judgment of Paris” the problem is a triplicated dilemma. As I see the Arlington Court Picture, the Sea Goddess, the Unveiled Lady, and the Water Carrier are all about redemptive tasks, intending to set right the disrupted cycle of love and vision. (See Blake Newsletter, 3 [May 1970] and 4 [August 1970], and Studies in Romanticism, 12 [1971].) In Night Thoughts no. 465 (IX, 47) Nature is shown to be undertaking this whole task by herself, but since it is still night time the best one can expect her to do is set a salutary precedent for eternal day.The evidence indicates that despite their prepossessing characteristics Mirth and her Companions are all in jeopardy, though some more clearly than others. I have suggested that the “Mountain Nymph Sweet Liberty,” in spite of her name, may not be as begin page 199 | ↑ back to top

good as she looks; however, it is important to recognize that the bow and arrow are not always unacceptable equipment. The interpreter must be alert not to conflate the golden bow of the Jerusalem hymn with Satan’s black bow. For example, Blake certainly represents a redemptive bow in the hands of the stately Diana figure in Night Thoughts no. 500 (IX, 82). And if the viewer cannot be quite easy even with this vision, he must accept Christ the Bowman in Night Thoughts no. 325 (VII, 53) or Hyperion in the sixth design for Gray’s “Progress of Poesy.” Qualifications such as these are essential to an accurate vision of all these “personifications”: to see what Blake did, we must see as Blake did.One naturally tends to admire a high-stepper like Jest, the only male figure in the front line with Mirth; it is true that, in the watercolor version, the glance he casts toward Youthful Jollity passes behind the back of Mirth and thus can seem dubiously surreptitious, but, in itself, this is hardly to be reprobated. In addition to his aforementioned resemblances to the images of Death and Satan, Jest also has a considerable resemblance to some of the deathly dancers in the frontispiece to Leonora, and he closely resembles the first reckless youth of the dream of the fanciful writer in Night Thoughts no. 14 (I, 9—reproduced in Blake’s Visionary Forms Dramatic, pl. 82), particularly in the engraved version, which is reversed. The fact that in this sequence the youth is directly entrapped and done in by a woman may lead us to prophesy that Jest has a similar fortune in store. But it is noteworthy that in both engraved versions Jest is depicted looking straight ahead, which indicates that he may not fall for some unworthy creature after all.

The primary analogues to the figure of Youthful Jollity are more unequivocally favorable. Her face as it is represented in both engraved states, particularly the first, is very like that of the imposing woman at the viewer’s left in the front row of “The Spiritual Condition of Man” (no. 33, Fitzwilliam catalogue). Preston in his commentary on the picture (Bentley and Nurmi no. 1783) identifies her as Faith and refers to her peculiar topknot of hair as a Hindu jatta; in posture, however, Youthful Jollity is much closer to the indubitable figure of Hope represented at the right in the front row of this picture. From this perspective, when we compare the dancers who accompany Mirth with the clownish dancers of Death in the Leonora frontispiece, we understand that, whatever the resemblances, it is the contrasting ethical status of the two sets of figures that is of most importance.

Still, it is not possible to exculpate Kitty and her adventure, though this escapade is probably intended to be risible rather than tragic.

Of the companions of Mirth Kitty is obviously

begin page 200 | ↑ back to top in most potential danger. Ever since the aforementioned “Blind-man’s Buff” in Poetical Sketches, a poem which echoes L’Allegro and contains a “Kitty,” Blake fans had been warned that too much fun may be harmful, and anyone can see that the latter Kitty has picked up sinister companions. One may recall several other women who are similarly threatened. There is Oothoon, who flees from Bromion on the titlepage of VDA ii. Then there is Sense, who evidently does not even try to run fast enough to escape the pall of Death in the aforementioned Night Thoughts no. 81 (III, 6) [fig. 5], since she appears quite unaware of the danger (see the article by Helmstadter for further discussion of this picture). Very like her is poor Vanity, who dances on tiptoe on the edge of the grave in Night Thoughts no. 253 (VI, 32) [fig. 10]. At the MLA seminar David Erd-man wisely asked whether I was postulating an invisible grave in front of Kitty that would make her plight equivalent to that of the girl in Night Thoughts. I hope I made a convincing denial. The point is that Kitty is in trouble, like Vanity, but has her eyes directed up to the source of the danger; consequently, she is more likely to fall up because of the machinations of Batty and Assy. Her fortune is likely to be equivalent to that of the girl trapped in the element of water in Il Penseroso 9 by a wingy-finned female who deploys her toils from a clam shell. To strengthen this connection I showed four slides of Blake’s designs for Gray’s “Ode on the Death of a Favourite Cat,” which were kindly loaned by Irene Tayler; design 1 shows the fish with bat-wing-type fins, design 3 features a curve in Selima’s tail like that in the cue of Kitty, and design 5 shows the nymph falling in a position very like that of the fallen woman in Il Penseroso 9. I also showed Cat-Ode design 6 to indicate how, in the resurrection of Selima, Blake imagined a future for her beyond Gray’s powers of projection; the implicit thought is that, though Kitty may be swept off her feet, it is possible that she may also get her feet on the ground again and then assay a more worthy transcendence.Kitty’s other betrayer appears in a pair of Night Thoughts designs, nos. 389 and 390 (VIII, 43 and 44) [figs. 11 and 12]. Here Assy is shown first beating a drum, accompanied on the pipe by another sly creature, in a military recruiting team that is appealing to a sweet young man to get a piece of the action. Then, in the second design, the recruiters seem to have hooked him, since the young man is moving to follow them; Assy is shown here high-stepping in triumph, like Jest, while one of his now two cohorts is a sly Kitty. The fond young man is about to be hit by three arrows from bows operated from above by three putti.

What is in store for Kitty if she becomes disengaged from Mirth is doubtless comparable to what will happen to the young man as a redcoat. The undeveloped area of Cranks in the watercolor version makes prediction dubious, but it would be realistic to expect the young man to become a murderer and Kitty a good-natured whore; the considerable resemblance of her (engraved) hat to that of the Wyf of Bath in the Canterbury Pilgrims (Separate Plates, pl. 27) makes this seem more probable. The area by Laughter’s left knee, rising from Assy’s hand, has been taken begin page 201 | ↑ back to top up in the engravings by a small woman who rises while looking at herself in an oval mirror. Blake employs mirrors frequently in the Night Thoughts designs and elsewhere, perhaps not always in their traditional signification, but it would appear that here a trivial Vanity of Vanities is clearly depicted. Similarly the more developed figures in the engraving of the pitcher-pourer and the goblet-receiver do not require analogies from Night Thoughts to make us suspicious; however, a particularly close relation is in no. 455 (IX, 37) [fig. 13], in which an old planetary spirit pours from a pitcher to serve a young planetary spirit who holds out a flat basin. This way of getting high is not propitious, not, at any rate, as depicted in the first state of the engraving.

Finally one must observe the connection between the family group of three at one o’clock and the drastically relocated arm and hand of Mirth in the second state of the plate. There Mirth is shown fostering the transfer of the babe from the mother to the father. As I see it, the resemblance to the aforementioned colorprint “Pity” is not discrediting. The colorprint is ambiguous insofar as it invites us to consider that Pity is promising in its inception but may be maleficent in its nurture. Evidently the more strenuous training envisioned by the haloed father in the second state of Mirth will be a better education. But the assistance per se given to the newborn-babe in the earlier colorprint was not mistaken. Also relevant are the struggles of the Good and Evil Angels for Possession of a Child in MHH 4 and the corresponding colorprint (no. 23 in Butlin’s revised Tate Gallery catalogue). The genders in the various versions of this design are problematic, but the more maternal figure always protects the child from the awesome male. In the presence of Mirth a properly cooperative egalitarian relationship is established, a relationship, indeed, of Innocence, in which there is sharing rather than sulking.

Irene Tayler suggested at the MLA meeting that the design of Mirth and her Companions is profoundly concerned with sexual problems and that the analysis of Mirth becomes increasingly less favorable in the engraved states than it was in the watercolor. At this time I am still unable to imagine how the second part of this interpretation can be sustained. Certainly the darkening of the picture is no mark against its regenerative implications. Blake’s own design for the regenerate man in Death’s Door (Separate Plates, pl. 25) was much darker than Schiavonetti’s comparatively bright and cheerful version. Perhaps I should add parenthetically a point I made in an earlier article, that the decapitated man in the upper panel of the parody version of regenerate man (Separate Plates, pls. 23, 24) has a cat head as one of his available masks. I suppose this to be one of the masks of Cromek, the headless man, though it may also have had particular associations with Skofield. But the judgment against Kitty in L’Allegro I cannot be as severe; when in company with Mirth she is less deceiving than deceived. With her arm relocated, Mirth is enabled both to foster the family and, perhaps, to guide Liberty into the paths of sweetness, rather than into those of self-righteousness. If Kitty appears under the

dispensation of Mirth and yet is seduced to aspire no higher than foolish lower Cranks, there can be no help for her. After all, the comic mode has its true prophets, exemplified by the higher flyer with the scroll, who may be taken to signify the great artists since Aristophanes who have also labored for our freedom from Care. In the end the music of Mirth’s wreathed Smiles is not delusive, as are the scrannel pipes of the Jovial Muses to Spare Fast in Il Penseroso 7 or the wrangles of Platonic airy nothings for benighted Milton himself in Il Penseroso.What then of the inscription scribbled on the plate to accompany the unfinished second state? It may be explanatory, but there are several different ways to read it. Possibly Blake felt frustrated because he couldn’t get the right foot of Mirth to come out satisfactorily after having done so much work on the plate. He might also have decided that, since the activities of most of the figures can be reduced to vanity by the technique of ironic regard, he himself had accomplished in the picture nothing better than a comprehensive anatomy or epitome of Vanity, and that nothing “can be foolisher than that.” But I believe that the activities of the family and the (now-haloed) flyer on either side of Mirth’s redrawn left arm are both above reproach, and that we must also consider the halos added to the figures of Laughter and even the wine-pourer (“First were created wine & happiness,” E 626) in begin page 202 | ↑ back to top the second state of the engraving. In the last analysis the irony in the inscription redounds on Solomon’s head: in the end the Vanity of Cynicism is the greatest Vanity of all. Consider, for instance, the example of “our friend Diogenes the Grecian” mentioned in MHH 13 and epitomized in his famous encounter with Alexander the Great and Aristotle in front of his barrel; this is depicted in Night Thoughts no. 469 (IX, 51). Diogenes was supposed to have been a Cynic but Blake knew him to be a prophet, one who did not have to read a book to understand that Solomon’s kind of wisdom must have been uttered by a sage who had grown weary of life. Nevertheless, Blake was careful to show us that, though Diogenes had abjured almost everything else, he had not given up books.

If one will lift up his eyes to the good book of the heavens, though it be opened by the sober wise figure of Night, who resembles Melancholy, he will see a goal for regeneration—as in Night Thoughts no. 501 (IX, 83) [fig. 14]. This is what Milton does in the end in Il Penseroso 12, as he looks up and sees the starry heavens humanized while a center opens beneath the pathetic, futile vanities that are unable to rise above the surface because they want to fly before they have learned now to benefit from the companionship of Melancholy.

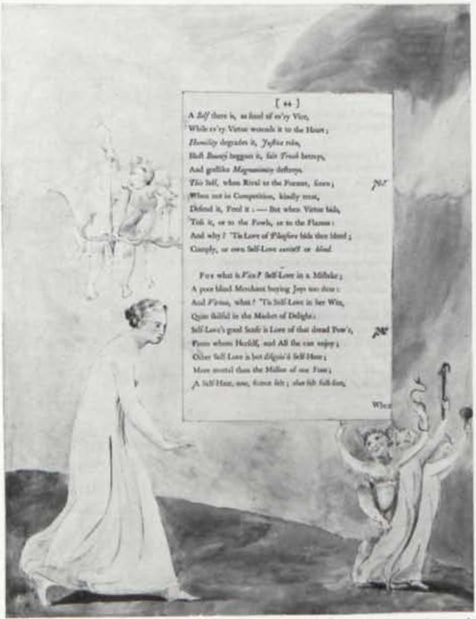

![[83]

To Christian Land, or Jewry; fairly writ

In Language universal, to Mankind:

A Language, Lofty to the Learn’d; yet Plain,

To Those that feed the Flock, or guide the Plough,

Or, from its Husk, strike out the bounding Grain!

A Language, worthy the Great MIND, that speaks!

Preface, and Comment, in the Sacred Page!

Which oft refers its Reader to the Skies,

As pre-supposing his First Lesson there,

And Scripture-self a Fragment, That unread.

Stupendous Book of Wisdom, to the Wise!

Stupendous Book! and open’d, Night! by Thee.

By Thee much open’d, I confess, O Night!

Yet more I wish; but how shall I prevail?

Say, gentle Night! whose modest, maiden Beams

Give us a new Creation, and present

The World’s great Picture, soften’d to the Sight;

Nay, Kinder far, far more Indulgent still,

Say, Thou, whose mild Dominion’s Silver Key

Unlocks our Hemisphere, and sets to view

Worlds beyond Number; Worlds conceal’d by day

17

M1

Behind](img/illustrations/NightThoughts501.5.3.bqscan.png)