article

begin page 166 | ↑ back to top

“They murmuring divide; while the wind sleeps beneath, and the

numbers are counted in silence”1↤ 1 Blake, The French Revolution, line 266 in

Blake Complete Writings, ed. Geoffrey Keynes (Oxford: Oxford UP, 1974) 146.

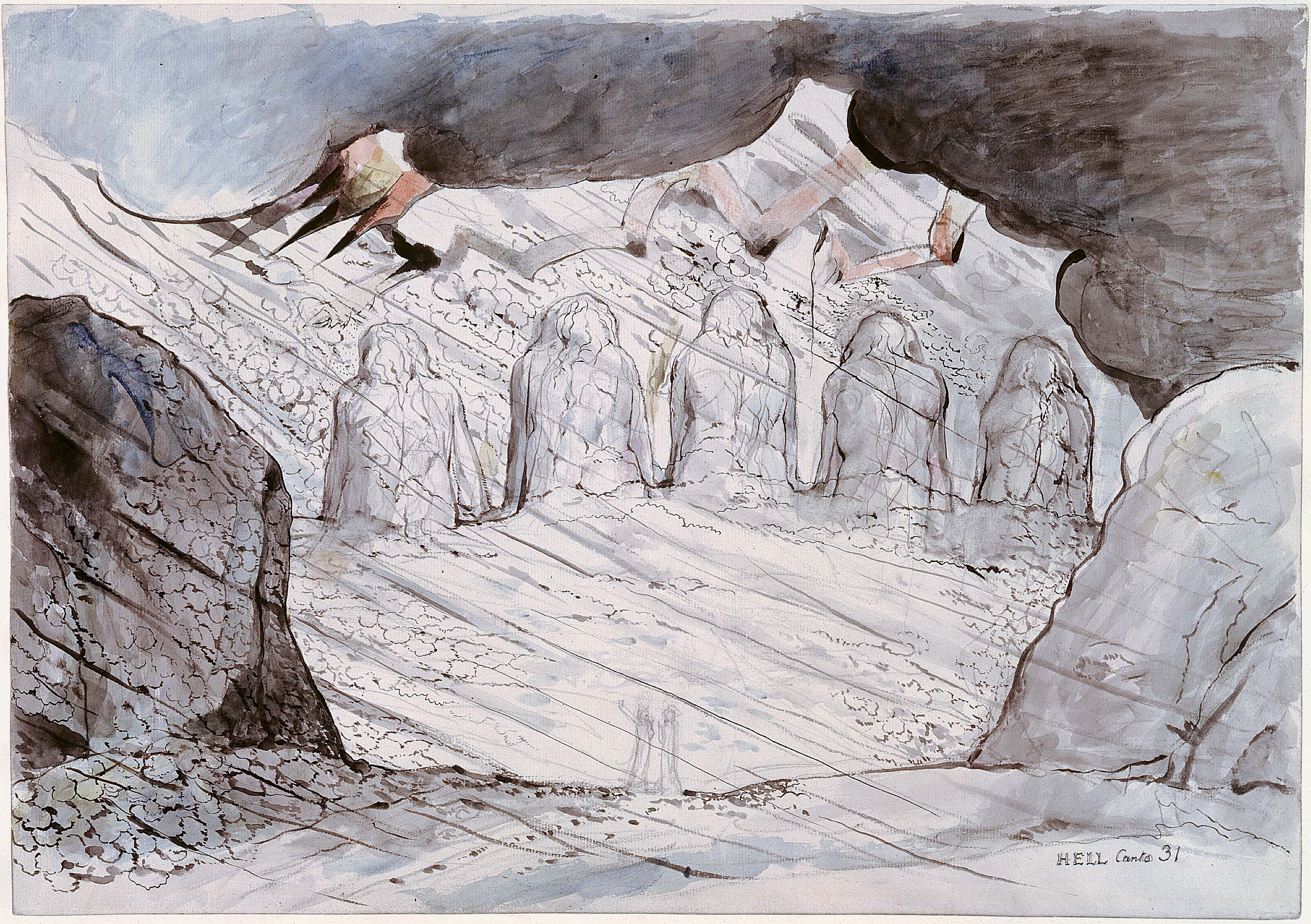

The Dispersal of the Illustrations to Dante’s Divine Comedy

Blake’s illustrations to Dante’s Divine Comedy, the unfinished series of water colors and drawings on which he was working at the time of his death, are generally regarded as among the greatest of all his later works. This series is dispersed among several public collections in three countries, which militates against attempts to examine the series as a whole, particularly as there is still no adequate edition reproducing all the water colors in color.

In my essay I trace in detail the process whereby the series of Dante water colors was divided and dispersed in 1918, and the responses such division occasioned. I do not attempt to judge either the legitimacy or the legality of such a proceeding, preferring to accept it as a fact of history determined by economic and administrative factors operating at the time. In the study of Blake we are all dependent on the history of the works that have come down to us. It is a legacy of this process that works now in institutional collections are located in different places and are likely to stay there. Both accident and design have contributed to this state of affairs.

The sale of the Linnell collection of works by William Blake at Christie’s in London on 15 March 1918 remains a landmark in the process of transfer of Blake’s works from private ownership into the possession of public and national institutions. The collection of works commissioned and otherwise acquired by John Linnell in the last decade of Blake’s life remained intact throughout the nineteenth century, but by 1918 its dispersal seemed unavoidable. As early as 1913 Charles Aitken (1869-1936), Keeper (from 1917, Director) of the National Gallery of British Art (as the Tate Gallery was then designated), and Laurence Binyon, Keeper of Prints and Drawings at the British Museum, had made approaches to Linnell’s descendant Herbert Linnell (d. 1937), a solicitor and partner in the London firm Finnis, Downey, Linnell, and Chessher, on the subject of the anticipated dispersal of the collection. On 4 December 1913 Linnell replied to Aitken: ↤ 2 Public Records of the Tate Gallery, Acquisition File 10 BLAKE (hereafter cited as TG).

With regard to our collection, it will, at some future date, have to be dispersed, although I grieve to think that it should become necessary. I will certainly let you know in good time before anything is done. I had a similar request from Mr. Binyon some little time ago. My hope is that all the works will be retained in this country and not find their way to America.2

This approach came to nothing, and four years passed before the question of the dispersal of the Linnell collection once again arose. In the event, announcement of the sale in early 1918 could not have come at a worse time for the Tate Gallery. The director had no purchase grant at his disposal, wartime circumstances had removed most potential sources of funding and relegated the acquisition of works of art by the nation to a very remote place in the public consciousness, and the imminent implementation of the Curzon Report on the administrative separation of the Tate Gallery from its parent body the National Gallery necessarily resulted in a period of managerial uncertainty for the Gallery.

In particular, attention centered on lot 148, the unfinished series of 102 illustrations to Dante’s Divine Comedy, which in the 1840s Samuel Palmer recalled seeing at their inception: ↤ 3 G. E. Bentley, Jr. Blake Records (Oxford, 1969) 291. The date 1824 has been criticized as too early, but no conclusive proof has been assembled for disputing Palmer’s dating of the encounter.

On Saturday, 9th October, 1824, Mr. Linnell called and went with me to Mr. Blake. We found him lame in bed, of a scalded foot (or leg). There, not inactive, though [almost] sixty-seven years old, but hardworking on a bed covered with books sat he up like one of the Antique patriarchs, or a dying Michael Angelo. Thus and there was he making in the leaves of a great book (folio) the sublimest design from his (not superior) Dante. He said he began them with fear and trembling. I said “O! I have enough of fear and trembling.” “Then,” said he, “you’ll do.”3

At some point prior to 1918 the “great book (folio)” had been separated into its constituent leaves, and Aitken was anxious that the 102 drawings that comprised the Dante series should be treated as separate items in the Christie’s sale. Neither the Tate Gallery nor any of the other institutions that had their eye on the Dante drawings could afford to bid for the entire series, and there were real fears that only an American private collector would be able to raise the necessary finances to acquire all 102 drawings. Aitken’s attempts to persuade Herbert Linnell to subdivide lot 148 were unsuccessful. On 11 March 1918 Linnell wrote: begin page 167 | ↑ back to top

I submitted your proposal to Messrs. Christie Manson & Woods and I have discussed the matter with Mr. Hannen to-day, and, in view of what he tells me, I am afraid the sale will have to go through with the catalogue as settled. It would only create difficulty and trouble, probably in more than one quarter, to do anything else. Had I heard from you before the catalogue was settled, the position would have been different, although I must candidly confess I think the drawings ought to be kept together, as a whole. I realise it is impossible to secure this except by someone purchasing for his own collection, or to present to one of the Public Galleries. (TG)

The suspicion remains that the convenience of the auction house took precedence over the interests of either the vendor or the potential purchasers of the works.

A week of hectic activity ensued, as Aitken attempted to raise the money that would secure the Dante series for the Tate Gallery. He sent out a circular to the Gallery’s benefactors and associates, appealing for subscriptions: ↤ 4 Copy in TG.

The Trustees think that this is an occasion when some of those who have given evidence of their interest in the Gallery and goodwill & have consented to become Associates might be willing to help them either by subscribing or by securing financial support from others. . . . It is desirable that the intention of the Trustees to acquire some of the drawings at the Linnell Sale should be kept strictly private.4

Among those promising to subscribe were Sir Hickman Bacon, Mr. Geoffrey Blackwell, D. Y. Cameron, A. M. Daniel, Joseph Duveen, Frank Gibson, Lord Howard de Walden, Lady Jekyll, J. T. Middlemore, M. P., W. Graham Robertson, C. L. Rutherston, Arthur Studd, Mrs. Watts and Lady Wernher; the request was turned down by George Moore and May Morris, among others.

In addition to canvassing financial support, Aitken also had to ascertain the intentions of other collectors; assurances that they would not be bidding for the Dante illustrations were obtained from W. Graham Robertson, Archibald G.B. Russell (who wrote “You must get the Dante!”5↤ 5 TG. and Alice Carthew. In a confidential letter to Carthew, Aitken spelled out his intentions and expectations regarding the sale, assuring her that “we want most the ‘Dante’ in view of what is coming to the nation otherwise,” and that the expected sale price would be £6,000, of which he had already received assurances of £4,700. He continued, “It is possible Melbourne [i.e., the National Gallery of Victoria] or one or two rich benefactors may put up the rest. We

Division of the series was unavoidable if the Tate was to acquire any of the works at all, but even this eventuality seemed to present insurmountable problems at the beginning. Charles Ricketts, Aitken’s closest accomplice in the project, wrote that “Alas I know no one for the moment who would help over the Blakes. I rather hope America will also prove sniffey, our provinces are hopeless.”6↤ 6 Undated; in TG.

American participation was to be guardedly welcomed: mass purchasing of art works on the European market by American collectors with financial resources vastly superior to those at the command of their European counterparts was already a fact with which European collectors had to become reconciled, and Aitken and Ricketts appear to have wanted to involve American collectors in their plans in a secondary and subsidiary capacity, thereby heading off any attempt on their part at buying the Dante series outright. Shortly before the sale took place, Ricketts wrote to Aitken: ↤ 7 Dated “Friday 12” [March 1918]; in TG.

On principle I rather dislike the remnant being sold to America, i.e. part of it. I think the entire series as such has a National interest and America might think twice before purchasing what we don’t want. I also do not care for a gift to Liverpool; Liverpool has behaved badly, the act would not reconcile (vide Cecil Smith) they might even decline; if gifts are in contemplation I feel the BM [crossed out], Birmingham, Oxford, even Melbourne who all came to the rescue should have gifts, and if our £50 can strengthen the British Museum I am most keen that it should.7

In the absence of much of the correspondence that passed between museums and collectors at this time, many of the references in this letter begin page 168 | ↑ back to top (e.g., to Liverpool’s alleged bad behavior) remain tantalizingly obscure.

In his notes on the sale (TG), Aitken compared the listing of the Dante drawings in the Christie’s catalogue with that in Gilchrist’s Life of William Blake and annotated a copy of the Christie’s list, marking each drawing A, B, or C, in accordance with its presumed desirability. Such questions as the degree of completion of the drawing, the amount of color that had been applied to the original pencil sketch, and the quality of the design appear to have been considered in making such a value judgment.

Bidding began at 2,000 guineas (£2,100), and the Dante illustrations were bought at the sale for the sum of 7,300 guineas (£7,665), the National Art-Collections Fund acting as banker for an unofficial consortium of interested public institutions. Founded in 1903, the National Art-Collections Fund was (and is) devoted to enriching the public galleries and museums of Great Britain, and assumed this coordinating role with relation to the Linnell Blakes in accordance with its stated object: “to secure Pictures and other Works of Art for our National Collections.” An invoice (for the Dante drawings and other works bought by the consortium) issued by Christie’s to “Tate Gallery, C. Aitken, esq” and dated 17 (or possibly 7) April 1918 reads: “To a/c as rendered £9022.13” (TG). In its subsequent 16th Annual Report (1919), the National Art-Collections Fund (of whose council Aitken was at this time an honorary member) reported that “The National Art-Collections Fund acted as banker for this combined purchase fund, thus enabling several public galleries which wished to acquire some of the drawings, but lacked funds to buy the whole collection, to combine in a joint purchase.”8↤ 8 National Art-Collections Fund: 16th Annual Report (1919), no. 276, 40. The Dante series appears as item 276 in the Fund’s list of acquisitions.

The subsequent division of the series was undertaken according to an elaborate codified system devised by Aitken and supervised by Binyon, the collector Charles Ricketts, and Charles Holmes of the National Gallery. Holmes had originally suggested a method of dividing the series: ↤ 9 Holmes to Aitken, 16 March 1918; in TG.

I have been amusing myself with thinking over a way to divide those Blake Drawings fairly so that nobody can feel aggrieved afterwards; and submit the appended suggestion for you to use or not as you think fit.

(1) Let each Institution be allotted one ticket for each complete £100 contributed towards the total of 7665, ie. 76 tickets in all.

(2) Let each Gallery choose one Drawing in the order of the magnitude of their several contributions; then put the remaining tickets into a hat and let each Gallery choose when its ticket is drawn out. This will distribute fairly the best 76 drawings.

(3) Let the 77th Drawing be chosen by the contributor of the odd £65.

(4) The remaining 25 Drawings, the least important of all, could then be dealt with in the same way, if desired.9

The system as finally applied, at a meeting in London, was a variant on Holmes’s suggestion. The twelve drawings presumed to be the least important or attractive to the participants were put aside as the “débris” (Ricketts’s phrase) of the series, and the remaining 90 divided into three categories; each contribution of £250 entitled the participant to one share consisting of one drawing from each category. Charles Aitken drew up a memorandum on the procedure: ↤ 10 Photocopy received from National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

Purchase of 102 Illustrations to DANTE by WILLIAM BLAKE at the Linnell Sale at Christie’s, March 15th 1918.

The price was £7665. Ninety of the 102 drawings were completed. Twelve were so slight and in pencil as to be of little value. The ninety finished drawings were divided into three categories:

30 “A” Drawings

30 “B” Drawings

30 “C” Drawings

To work a plan out in round figures it was assumed that £7500 was subscribed as follows in £250 shares there being thirty such shares for the ninety drawings:

it was decided to allot on the principle of one £250 share entitling to a selection of 1 “A” drawing, 1 “B” and 1 “C”. Melbourne, therefore, having 12 £250 shares received 12 “A”, 12 “B” and 12 “C” drawings, 36 in all, as the Tate also: the British Museum 6 each, and Oxford and Ricketts and Shannon 3 each.

Melbourne £3000 (12 shares) Tate Gallery £3000 (12 shares) British Museum 500 (2 shares) Birmingham 500 (2 shares) Oxford 250 (1 share) Mr. Ricketts & Mr. Shannon 250 (1 share)

The twelve slight drawings were taken over by the Tate for the balance (£7665 - £7500) £165. They are not worth even this sum probably and one of the other galleries wished to take them.

Melbourne had the first choice and in picking a careful plan was worked out and adopted with the approval of all galleries concerned, to secure fairness proportionate to the size of the subscription.10

In the event the Tate’s proportion was reduced from 36 drawings to 24.

Ricketts wrote a postmortem on the meeting in a letter to Aitken, and this gives something of a taste of the atmosphere in which the series was divided: ↤ 11 Undated; in TG.

I thought Birmingham’s selection masterful in every way; I admit I have come out monstrously well.—I thought Binyon impassive, rather asleep in fact. I wonder what became of Oxford who ought to have been there. I agree with you Ross behaved splendidly, he secured a sound average without undue claims upon that which should be here. I only regret the Giant which I think is one of the 5 best. So all is well and we are all to be congratulated. I think the series will prove most popular in the best sense with visitors to the Tate, it would have been a scandal and a disaster had the set left the country.11begin page 169 | ↑ back to top

Elsewhere Ricketts congratulated Aitken on the successful conclusion of the project to acquire the drawings, “I feel you worked heroically in this matter which was badly started.”12↤ 12 Postcard dated 29 April 1918; in TG. Congratulations came from various quarters. Alice Carthew wrote to Aitken—“I was so glad to see that you had got the Blake Dante. In the course of sharing up, I wondered whether by any chance you might have a picture or two over that might be offered to a private person or two?”13↤ 13 21 March 1918; in TG. To which Aitken replied, “I think we should very probably be glad to part with some of our Dante drawings in order to reduce our commitments. I believe America would like some. I will keep you informed, when we have settled details.”14↤ 14 23 March 1918; copy in TG. Among the letters of congratulation was one from George H. Leonard, of the University of Bristol; he had lectured on Blake to the troops on the Western Front (but been prevented from showing slides of works by Blake—slides of works by Watts, however, were permitted), and wrote to Aitken: ↤ 15 7 April 1918; in TG.

I wanted to write as a private person, to thank you for what you have done in getting these things for the Nation—and Empire. There are public thanks, I know, of a sort—but I thought I should say that there are private people who care very much indeed to know that treasures like these will now be available for all, and who feel they must add their private thanks to you and others.15

Unfortunately, not everybody was pleased with the outcome of the division of the series. Robert Bateman and Walter Butterworth, Curator and Chairman respectively of the Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, had offered a sum of £500 towards the purchase, “if assured of first choice of good drawings” (TG). The extant correspondence does not make clear whether this stipulation was unacceptable to the organizers of the purchase, whether the offer was received after the purchase had already been undertaken, or whether the offer was simply mislaid or otherwise forgotten; in any

[View this object in the William Blake Archive]

Those concerned in forming a Fund to secure the Dante series and other Blake drawings, took no trouble to advise the Manchester Whitworth Institute, and perhaps similar galleries, nor to invite their co-operation. The W.I. [Whitworth Institute] Council knowing nothing of this project, decided to bid up to £2000. . . . you answered that “the majority decision was that those bodies who had joined in before the sale should divide out.” From this decision we were excluded and eventually we were offered certain drawings. . . . They can justly be described as almost the dregs of the collection. . . .16

And again, two weeks later ↤ 17 6 June 1918; in TG.

It seems extraordinary to me that when those concerned came to know of our efforts, before & after the sale, they carefully excluded our important British water colour Gallery from the possibility of acquiring a share of good Blake drawings. Doubtless you did your best in an emergency, but we have not been well treated.17

Elsewhere, Aitken wrote that Manchester’s Chairman, Walter Butterworth

did not consider that the proposition was a sound business proposition and he was not prepared to consider it. He felt that the Whitworth Institute had not been fairly treated as they had been prepared to come into the scheme before the sale and that therefore they were in a different category from the other Galleries which had not offered to provide money towards the purchase. He felt they ought to have been allowed to share in the first division and that we had been greedy. . . . the cream of the collection had been skimmed off and that which is left was a number of 2nd and 3rd Class Blakes which we and they did not particularly want. (TG)

With most of the correspondence missing or untraced, and that which is extant necessarily providing a selective and onesided picture, it is impossible to determine the rights and wrongs of this misunderstanding. Similarly, Mr. Erskine and Mr. James L. Caw, of the National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh, didn’t consider the purchase of the works they were offered to be justified.

The result of the distribution of the Dante drawings was that the Tate Gallery acquired twenty of the drawings, drawing on funds from the National Gallery (£581 from the Clarke Fund), the National Art-Collections Fund, and begin page 170 | ↑ back to top a number of individual benefactors, including Lord Duveen (who contributed £2,000), Lady Wernher and Sir Edward Marsh. A typed report for the National Art-Collections Fund reads:

The 90 best were divided into 30 shares of 3 each (1A, 1B, 1C) @ £250 a share.

The National Art-Collections Fund has 12 shares = 36 drawings, and also took 12 debris drawings, from the 90, for £165 [;] the Fund thus had 48 drawings in all. Of these 48 drawings, it is prepared to offer 20 A drawings to the National Gallery, British Art, and 20 B drawings to be sold in America - if possible.

1 to be presented to the British Museum (Purgatorio, Canto 2, “The Angel Boat”) in respect of an extra £50 subscription by Mr. Charles Ricketts.

1 to be presented to Truro in respect of Mr. de Pass’s subscription of £50 - to be selected out of the B drawings (21 in all) leaving 20 to be sold in America.

6 very slight drawings (as under) to be presented to the British Museum, Print Room.

(Hell cantos 21, 24, 33, 33; Parad. cantos 19, 28). (TG)

The remainder of the Dante drawings went to the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne (36 drawings, through the Felton Bequest), the British Museum (13 drawings), the City Art Gallery, Birmingham (6 drawings, through the Public Picture Gallery Fund), the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford (3 drawings) and the Truro Museum (1 drawing, presented by Alfred de Pass). Charles Ricketts acquired four works, which in 1943 entered the Fogg Art Museum at Harvard University, together with a further 19 works which had passed through various American private collections. Thus the unfinished series is currently divided between seven public and university collections in England, Australia, and the United States—a situation that would appear destined to remain unchanged.

The Fogg Art Museum,18↤ 18 Letter to the writer from Abigail G. Smith, Assistant to the Archivist, 14 January 1985. the City of Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery,19↤ 19 Letter to the writer from Stephen Wildman, Deputy Keeper (Prints & Drawings), Department of Fine Art, 2 January 1985. and the Ashmolean Museum20↤ 20 Letter to the writer from Nicholas Penny, Keeper of Western Art, 12 December 1984. no longer have in their possession any records of the transactions leading to their acquisition of the Dante drawings in their collections, but the other two institutions (Truro and Melbourne) have most helpfully located the relevant correspondence in their files at my request.

Among recipients of the subscription notice sent out by Charles Aitken (see above) was Alfred de Pass, the generous and frequent benefactor of the Royal Institution of Cornwall, Truro. On 21 July 1918 he wrote to George Penrose, Curator of the Institution, “Mr. Charles Aitken of the Tate Gallery writes me that the National Art Collections Fund have at my request decided to give a Blake drawing of the value of £100 to the Truro Museum and will go through them with me to see which one to present.”21↤ 21 Transcribed in letter to the writer from H. L. Douch, Curator, 10 December 1984. Later in the same year, on 7 November 1918, de Pass wrote to Penrose: “Now I hear from Mr. Aitken, Tate Gallery, that he and Mr. Holmes of the National Gallery have selected a Blake water colour drawing. The Purgatorio Canto 9 The Angel with the sword marking Dante with the sevenfold P.”22↤ 22 Transcribed in letter to the writer from H. L. Douch, 10 December 1984. Unfortunately, de Pass (whose subscription appears to have been conditional on one of the drawings being sent to the Truro Museum) seems to have been less than impressed by the drawing when he actually saw it: “I saw the Blake drawing we are to have. Some would think it dear at £ 3.10.”23↤ 23 Transcribed in letter to the writer from H. L. Douch, 10 December 1984. Original letter dated 9 May 1919.

The works that came into the possession of the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, were acquired under the terms of the Felton Bequest, on the recommendation of its London adviser, Robert Ross. Ross, a friend of Wilde, Beardsley, and Beerbohm, had been appointed the fifth successive London Adviser to the Felton Bequest in May 1917, but his tenure of the post was cut short by his untimely death in October 1918. On 8 March 1918 Ross cabled the Felton Trustees: ↤ 24 In possession of the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne; photocopy sent to the writer.

Christies sale fifteenth March Linnells famous collection Blakes see Gilchrists life volume two page twentytwo and following last possible public sale Blakes keen competition high prices expected if Blakes wanted Ross strongly recommends various purchases cable general instructions up to fivethousand guineas.24

A handwritten note appended to a terse report to the Committee reads “Approved. Felton Committee. 14.3.1918.”25↤ 25 National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne; photocopy sent to the writer. On 30 June 1918 Ross wrote an exhaustive account of the purchase, addressed to the Secretary of the Public Library, Museum and National Gallery of Victoria, including the following: ↤ 26 National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne; photocopy sent to the writer.

I am satisfied with the result, and only hope that the purchase will satisfy the Trustees of the Felton Bequest and the National Gallery; and that the drawings which I was able to secure will arouse in Melbourne as much interest and appreciation as they did in London. . . . I am well aware that Blake’s art does not appeal to everyone, and that the acquisition of so many examples might be open to criticism from those to whom his peculiar genius makes no appeal. . . . The action of the Melbourne Trustees is deeply appreciated by the Trustees and Directors of the English Galleries, and I think I can say that it will lead in the future to great benefits so far as the Melbourne Gallery is concerned, a precedent of mutual goodwill and understanding having been established.26

Although the trustees approved the purchase, the public were distinctly less favorable when in 1921 the drawings eventually arrived in Melbourne. The art critic of the Melbourne Argus wrote: ↤ 27 Quoted in Leonard B. Cox, The National Gallery of Victoria 1861-1968 (Melbourne, 1971) 84.

Thirty pictures by [Blake] are on view, and the price paid was £4,000, which seems to be very much in excess of their value . . . no justification can surely be shown for the purchase of so many artistically inferior pictures, which will no doubt before long find their way to the cellars.27

These expectations appear to have been realized: “Met with hostility and considerable public criticism on their arrival in 1921, they lay unused in drawers for over twenty years, until resurrected by Daryl Lindsay. . . .”28↤ 28 Ursula Hoff, The Felton Bequest (Melbourne, 1983) 12. The delay in the arrival of the drawings in Melbourne was due to the photography and publication of the entire series while it was still in the capable hands of the National Art-Collections Fund, before begin page 171 | ↑ back to top dispersal to the various institutions on whose behalf it had been acting. With the help of Emery Walker, the Fund itself issued the facsimile series as a portfolio—one color plate accompanied the complete series in monochrome. On 30 May 1922 Sir Robert Witt, Chairman of the Fund, was able to report: “The Drawings by William Blake of Dante’s Divine Comedy, which we informed you were being published by the Society, have now been issued. We believed it to be in the interests of British art, and a worthy monument to a great English artist who never stood higher than he stands to-day.”29↤ 29 National Art-Collections Fund: Nineteenth Annual Report, 1922 (1923) 4. Two hundred fifty copies of the Blake portfolios were printed in 1922; the balance sheets of the National Art-Collections Fund for the years 1922 and 1923 (in the Annual Reports for 1923 and 1924) list an income from the sale of Blake portfolios of £550.13.5 and £37.2.6 respectively.

The dispersal of the Dante illustrations can be adduced as an example of the principle of entropy applying to art collections and to compound works susceptible to subdivision. In this instance most criticism of the proceedings would appear to be anachronistic and out of place. Conditions of finance and administrative control have altered so fundamentally in the subsequent seventy years that it is difficult, and probably fruitless, to speculate on alternative procedures that might have been implemented with the intention of assuring the integrity and completeness of the Dante series. Furthermore, the complete series could only be located (presumably) in one of the seven institutions which possess parts of it at present, and the problems of display of such a quantity of works would possibly outweigh any advantages that completeness might bring. There is much to be said for Cockerell’s opinion that, in some ways, “a quarter is more than the whole” (TG).

In addition, the presence of the Blake drawings in America and Australia has had a substantial influence on the growth of Blake’s reputation outside Britain, and it can be argued that the cultural claims of Cambridge, Massachusetts,[e] and Melbourne, Victoria, to the drawings of Blake are perhaps as great as those of London, Oxford, Birmingham, or Truro. Ultimately, the excellence of color reproduction in books and prints suggests that dispersal is not the tragedy that it might at first appear. Although a substantial number of the drawings have been reproduced in color, there is still room for a complete color facsimile edition of the Dante illustrations.30↤ 30 In particular see Milton Klonsky, Blake’s Dante: The Complete Illustrations to the Divine Comedy (New York: Harmony Books, 1980) and catalogue of exhibition Blake e Dante at Pescara, Torre de’ Passeri, Casa Dante in Abruzzi (Milan: Gabriele Mazzotta, 1983).

The writer gratefully acknowledges the generous assistance and advice received from Martin Butlin, Keeper of the Historic British Collection, Tate Gallery; Jennifer Booth, Archivist, Tate Gallery Archive; Joan Linnell Burton; Finnis, Christopher, Foyer & Co., Solicitors, London; H. L. Douch, Curator of the Royal Institution of Cornwall, Truro; Stephen Wildman, Deputy Keeper (Prints & Drawings) of the Department of Fine Art, City of Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery; and Irena Zdanowicz, Senior Curator of Prints & Drawings, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Crown copyright material in the Tate Gallery is reproduced by permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, London.