NOTES

NOTES ON SOME ITEMS IN THE BLAKE COLLECTION AT McGILL WITH A FEW SPECULATIONS AROUND WILLIAM ROSCOE

Blake Newsletter readers may not know that there is an interesting Blake collection in the Rare Book Room of the McLennan Library at McGill University.*↤ The preparation of this essay was aided by a grant from the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research at McGill. Diane Mayor brought the Grandison edition to my attention. It is a good collection, except for the lack of any original copies of Blake’s own poems or paintings. But it has a few original drawings, sets of the Job and Dante engravings, one of the four or five known impressions of the engraving of Edmund Pitts,1↤ 1 See Keynes, Engravings by William Blake: The Separate Plates (Dublin: Emery Walker, 1956), p. 78, and also his “William Blake and Bart’s” in Blake Newsletter 25 (Summer 1973). 9-10. the Linnell portrait of Wilson Lowry that served as the original design for Blake’s engraving,2↤ 2 See Keynes, Engravings by William Blake: The Separate Plates, pp. 86-87, and pl. 45. Lowry was the inventor of a ruling machine used for engraving, which Blake apparently used in his Dante engravings; see Ruthven Todd, “Blake’s Dante Plates,” TLS, 29 August 1968, p. 928. many of the books illustrated by Blake, and a good collection of facsimiles, critical works, and related items. The core of the collection was donated in 1953 by Mr. Lawrence Lande, and the Rare Book Room librarians and I have tried to fill gaps and keep the collection up to date, aided by further donations from Mr. Lande. In the course of working with the collection, I have come across several interesting items that I would like to describe, by way of both sharing and requesting information.

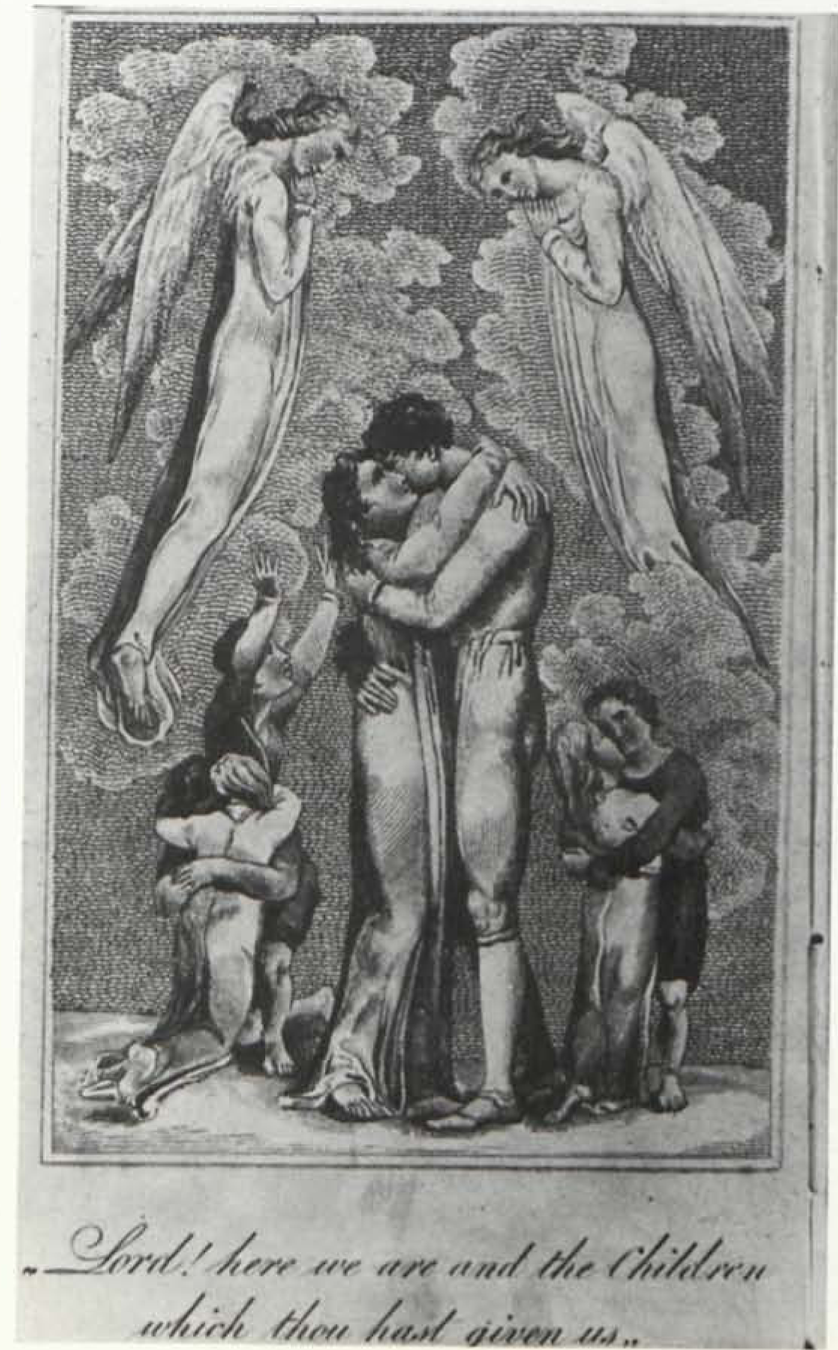

The first two are apparently plagiarisms. One is a much reduced—in all senses—and unsigned version of Blake’s “The meeting of a Family in Heaven” design for Blair’s The Grave, with a new text which is not from that poem (illus. 1). The dimensions of the frame line are 142 × 90 mm., and the plate has been bound in as frontispiece to a copy of Hayley’s The Triumphs of Temper, the twelfth edition with Blake’s engravings. The volume also contains two other prints glued onto the inside of the covers, one being Plate IX (one of Blake’s plates) for Vol. VIII of The Novelist’s Magazine, containing Don Quixote. The book has been signed “Ann Shipman” in what looks like an approximately contemporary, and very shaky, hand.

The “appearance of libidinousness” to which Robert Hunt objected in the original3↤ 3 See G. E. Bentley, Jr., Blake Records (Oxford: Clarendon, 1969), pp. 195-97. has been removed; in this version the husband’s hand remains decorously at his wife’s waist rather than openly enjoying the fullness of her buttock. One version of the philistine unwilling to give the artist in form and line his due? The angels’ wings have also had their free, erect Gothic curves cut down into a flaccid droop. The dynamism of the son entering from the right has been negated by placing him behind the group of children on the left. The three pairs of figures on the ground retain their general positions, but begin page 101 | ↑ back to top each pair has been reversed. Perhaps the changes were enough to protect the publisher; they were certainly enough to emasculate the design. Does any reader know anything of the book which this presumably once illustrated?

The second apparent plagiarism is a two volume edition of The History of Sir Charles Grandison. Both title-pages read “Formerly Published in Seven Volumes; the Whole now Comprised in Two. Cooke’s Edition. Embellished with Fifteen Superb Engravings.” The first volume then reads “London; Stereotyped and Printed for T. Kelly. 17, Paternoster-Row,” and is dated 1818; the second volume reads “London; Stereotyped and Printed for C. Cooke. 17, Paternoster Row; by D. Cock, and Co. Dean Street, Soho,” and is undated. At the end of both volumes is a colophon attributing the stereotyping and printing to D. Cock and Co. at 75 Dean Street, Soho. The edition is unrecorded as far as I have been able to check.4↤ 4 See the bibliography in Jocelyn Harris, ed., The History of Sir Charles Grandison (London: Oxford Univ. Press, 1972), I, xl. It is admitted that the list is “probably not complete” (I, xxxix). The British Museum Catalogue lists a “Cooke’s edition. Embellished with . . . engravings. 7 vol. London, 1817. 24°,” which I have not seen, but the date, number of volumes, and format (the McGill copy is 8°) seem clearly to mark this as a different edition. The layout of the text is not identical with that of The Novelist’s Magazine edition.

The date of 1818 on the first volume presents some difficulties, and the evidence suggests that there was an interval of several years between the printing and the publishing of this edition, or alternatively between the making of the stereotypes and the actual printing. The engraved illustrations are all dated between 19 May and 21 November 1811; D. Cock appears to have moved from Dean Street in 1815,5↤ 5 See under D. Cock and Co. in William B. Todd, A Directory of Printers and Others in Allied Trades: London and Vicinity 1800-1840 (London: Printing Historical Society, 1972). and Charles Cooke died in 1816.6↤ 6 DNB. The title-page of the first volume thus seems anomalous, and possibly replaces a previous one, either actual or planned.

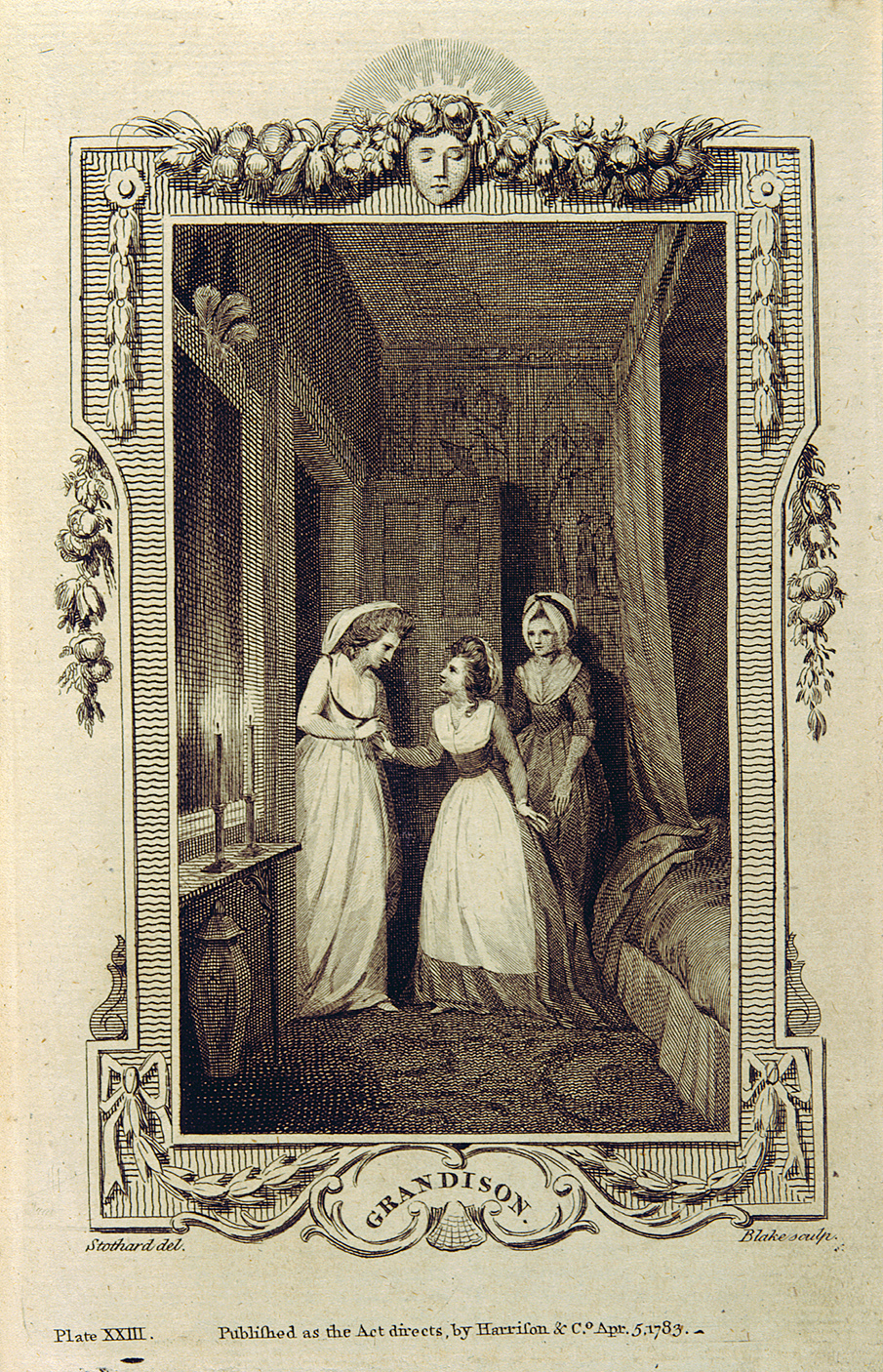

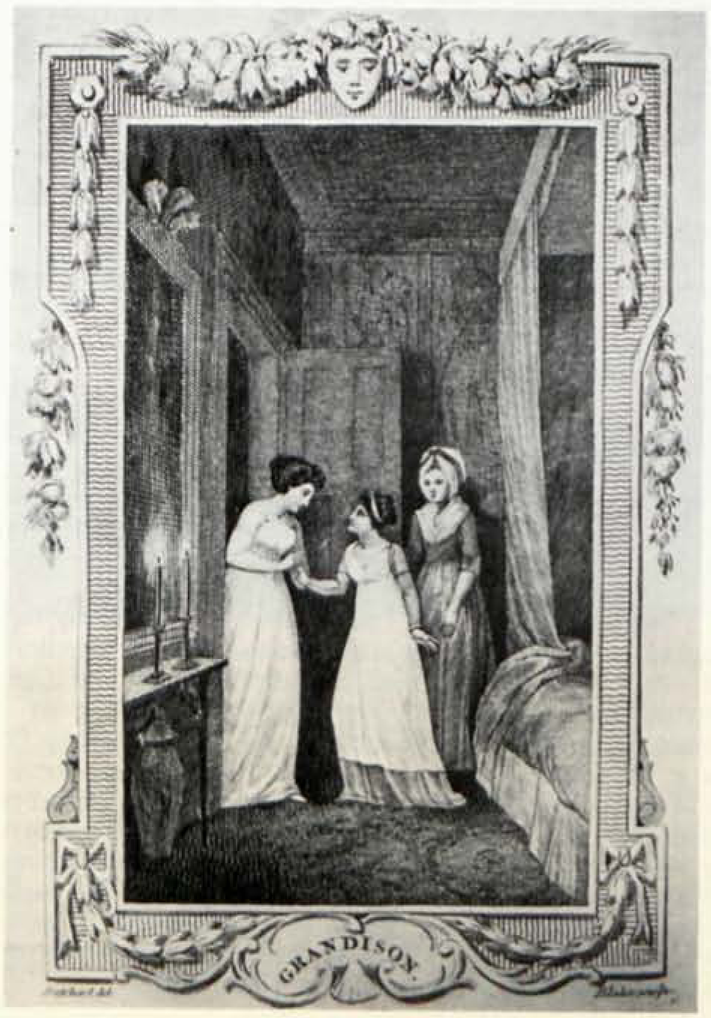

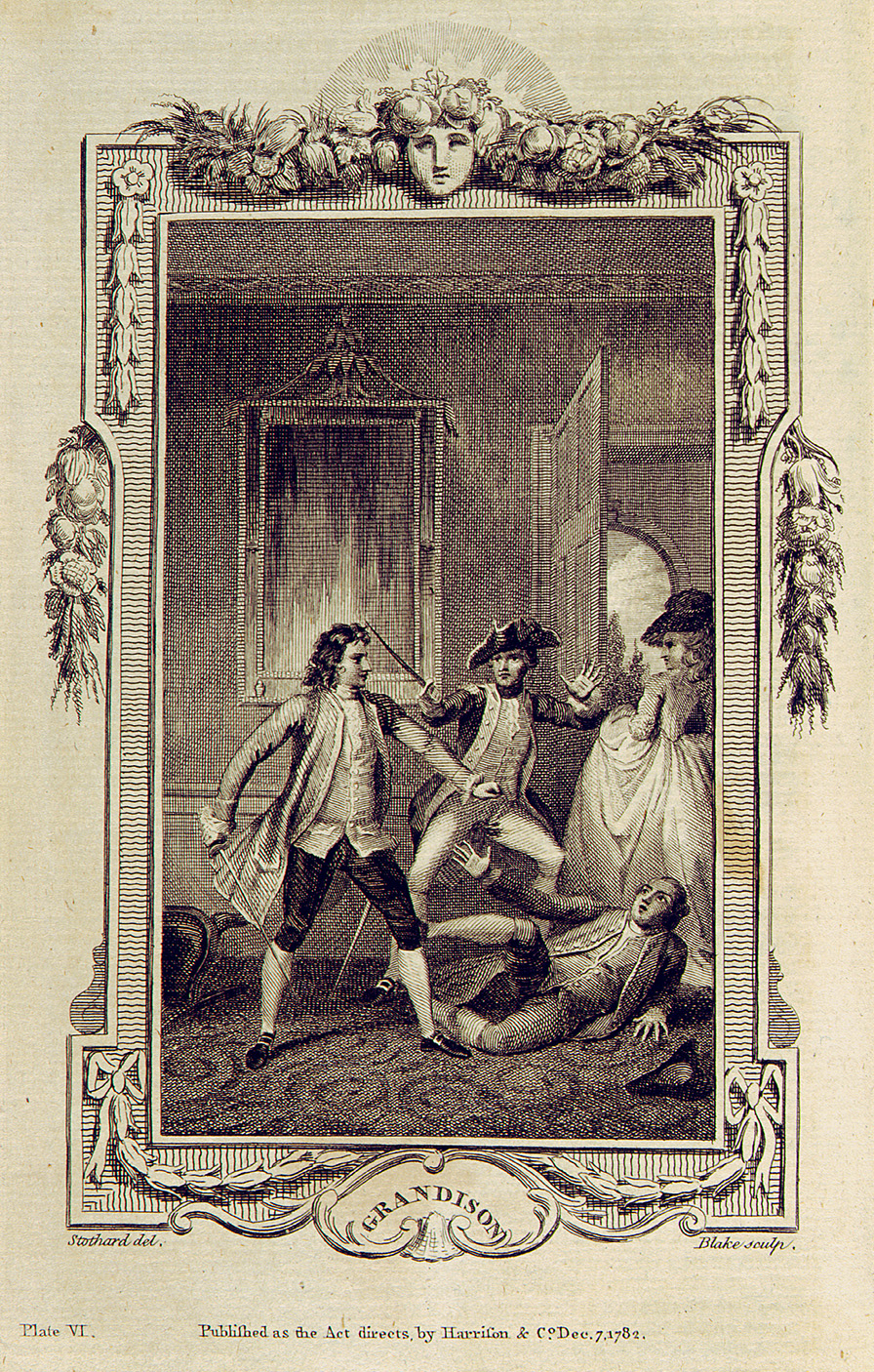

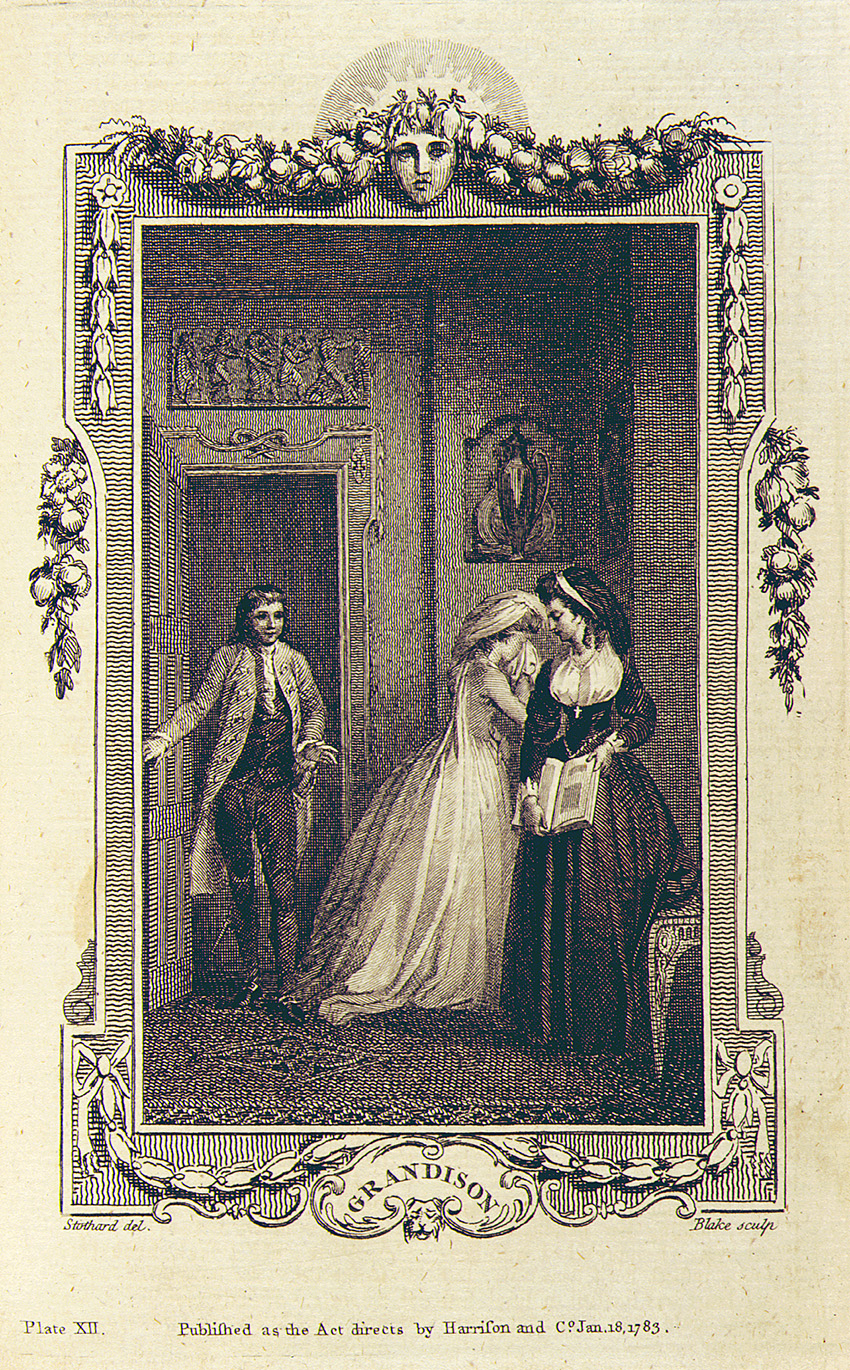

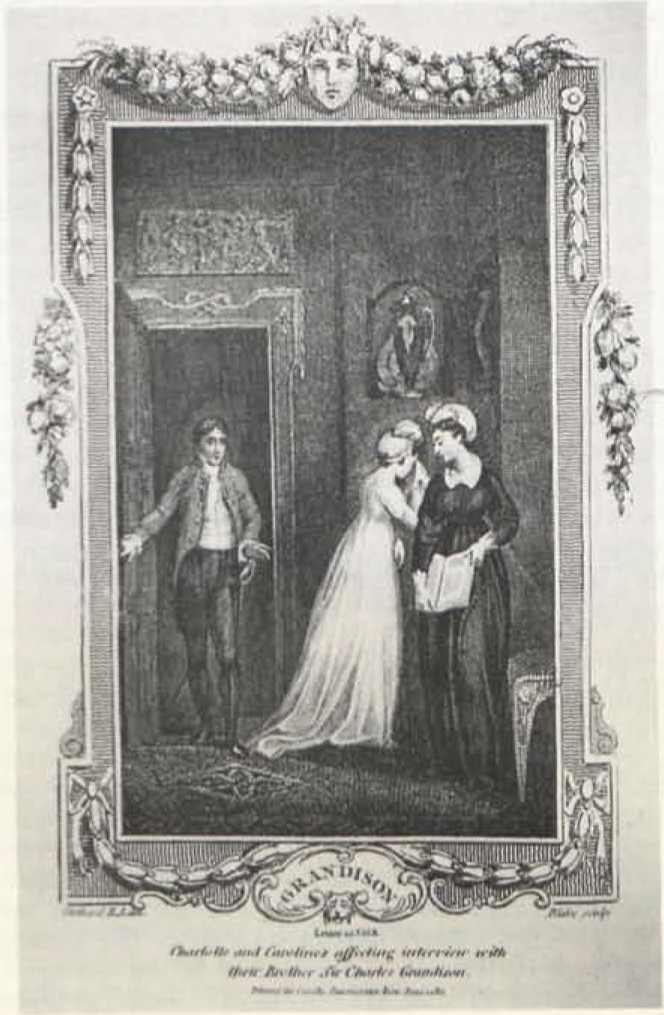

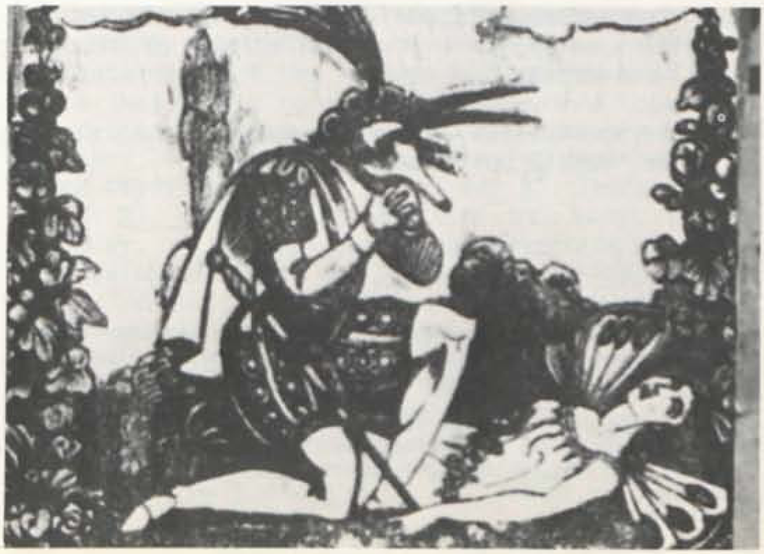

In any case, the “Fifteen Superb Engravings” are copied—or altered—from those in The Novelist’s Magazine edition, with plates designed by Stothard, of which three were engraved by Blake. The plates are in most respects very close to the originals, though there are substantial changes in the figures, especially in the women’s clothing, which has been updated to represent the high-waisted Grecian style of the Regency period.

The first plate, “Miss Byron paying a visit to Emily in her Chamber,” is dated 6 July 1811, and like all the plates is described as “Printed for C. Cooke, Paternoster Row.” The women’s costumes have been altered, and Stothard’s name replaced by “Scatchard.”7↤ 7 I have not found any trace of this name in any of the standard dictionaries of artists and engravers, and assume it to be a fiction. But many details, such as the irregular marks under the period after “sculp.,” are identical with those visible on the original illustration, suggesting that the same plate was used for both, or that the later plate was made from a stereotype of the original (see illus. 2).8↤ 8 The repetition of irregular marks which are not part of the engraving proper suggests that the later plate is not copied from the first by any method involving tracing. For helpful information on copying methods—and ethics—in the period, see G. E. Bentley, Jr., The Early Engravings of Flaxman’s Classical Designs: A Bibliographical Study, With a Note on the Duplicating of Engravings by Richard J. Wolfe (New York: New York Public Library, 1964). The methods discussed by Wolfe’s note both involve tracing. The second plate, “Sir Charles Grandison, disarming Captain Salmonet,” is dated 8 June or July (only the “Ju” is visible) 1811. Again Stothard’s name becomes “Scatchard,” but the changes are extensive enough to make it clear that a new plate has been used (see illus. 3). The third plate, “Charlotte and Caroline’s affecting interview with their Brother Sir Charles Grandison,” is dated 1 June 1811, but just after that one can barely make out the imperfectly erased original date, “Jan. 18, 1783,” making it quite clear that this is printed from the original plate reworked (see illus. 4). On this plate Stothard’s name remains, brought up to date with an “R.A.”9↤ 9 Stothard became an academician in 1794, according to the DNB.

In the edition as a whole, Stothard’s name has been changed to Scatchard on eight of the plates, remains unchanged on two, and is updated with an “R.A.” on five. In no case has an engraver’s name been changed, though Heath is advanced to J. Heath A.R.A.. The respect with which Stothard and Heath’s names have been treated in at least some instances clashes oddly with the changes of Stothard to Scatchard, which[e] would seem to imply conscious deception. I do not know whether Blake had a hand in the reworking of his plates or not; it seems very unlikely, though it is worth remembering that Blake felt decidedly hostile to Stothard by 1811, and he had previously done work for John Cooke, Charles’s father and predecessor.10↤ 10 See G. E. Bentley, Jr., Blake Records (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1969), p. 609.

The next group of items consists of original drawings, some of which raise questions of attribution and identification. One is almost certainly the original drawing for Thomas Butts’ engraving of “Venus Anadyomene,” reproduced most accessibly on Plate IX of Blake Records by G. E. Bentley, Jr..11↤ 11 See also Ada E. Briggs, “Mr. Butts, the Friend and Patron of Blake,” The Connoissuer, 19 (October 1907), 90-92, and G. E. Bentley, Jr., “Thomas Butts, White Collar Maecenas,” PMLA, 71 (1956), 1052-66. The drawing, which measures 114 × 76 mm., is attributed to Blake in a pencil note on the mat reading “by William Blake / From the Collection of Thomas Butts, the artist’s friend and patron.” The notation is not recent, but the hand is not Tatham’s, and Martin Butlin in a letter agrees that the drawing is most probably by Butts rather than Blake.

begin page 102 | ↑ back to topThe next drawing (illus. 5), measuring 130 × 100 mm., is more puzzling. It obviously depicts the creation of Eve, and has been attributed to Blake in a pencil note on the reverse of the drawing itself, in the same hand as the previously described note, and in exactly the same words. David Erdman and Martin Butlin have both commented, on the basis of a good photograph, that the drawing is not by Blake, and that seems clearly right. But the drawing has life and charm, and I should be glad to hear from any reader who has any ideas about the identity of the artist.12↤ 12 To my eye there is some analogy with the floating Eve and relaxed Adam of Fuseli’s painting of “The Creation of Eve,” though the drawing is clearly not by Fuseli.

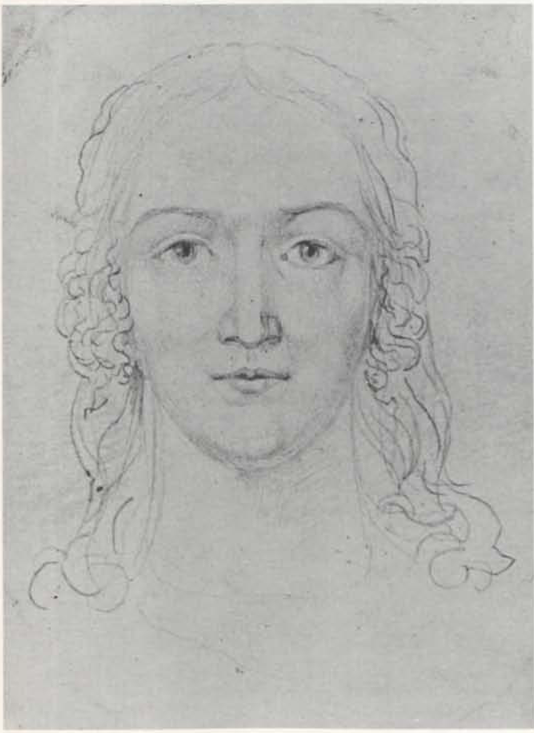

The collection also has two pairs of drawings which are certainly by Blake. One (illus. 6), 158 × 121 mm., is of a woman’s head, and was formerly described as a portrait of Blake’s wife. However, Geoffrey Keynes in a recent letter has stated that it does not resemble any of the known portraits, and may be a kind of visionary head. The drawing does show some resemblance in manner to the visionary head reproduced on the cover of Blake Studies, 5:1 (1972). The reverse is a very sketchy and faint drawing of a woman’s torso (illus. 7).

The other pair, measuring 275 × 213 mm., has as its recto (illus. 8) the drawing listed as No. 130 by W. M. Rossetti in his catalogue in the 1880 edition of Gilchrist’s Life, and reproduced there through the intermediary of an engraving by J. Hellawell.13↤ 13 See Alexander Gilchrist, Life of William Blake, 2nd ed. (London: Macmillan, 1880), I, 132 and II, 268. Rossetti gives it the tentative title of “Young burying Narcissa (?),” referring to an episode in Night Three of Young’s Night Thoughts, though adding

By glimmering thro’ thy low-brow’d misty Vaults,

(Furr’d round with mouldy Damps, and ropy Slime,)

Lets fall a supernumerary Horror,

And only serves to make thy Night more irksome (The Grave [London, 1743], p. 4, 11. 16-20), though the drawing is much earlier than Blake’s designs for Cromek’s edition of 1808.

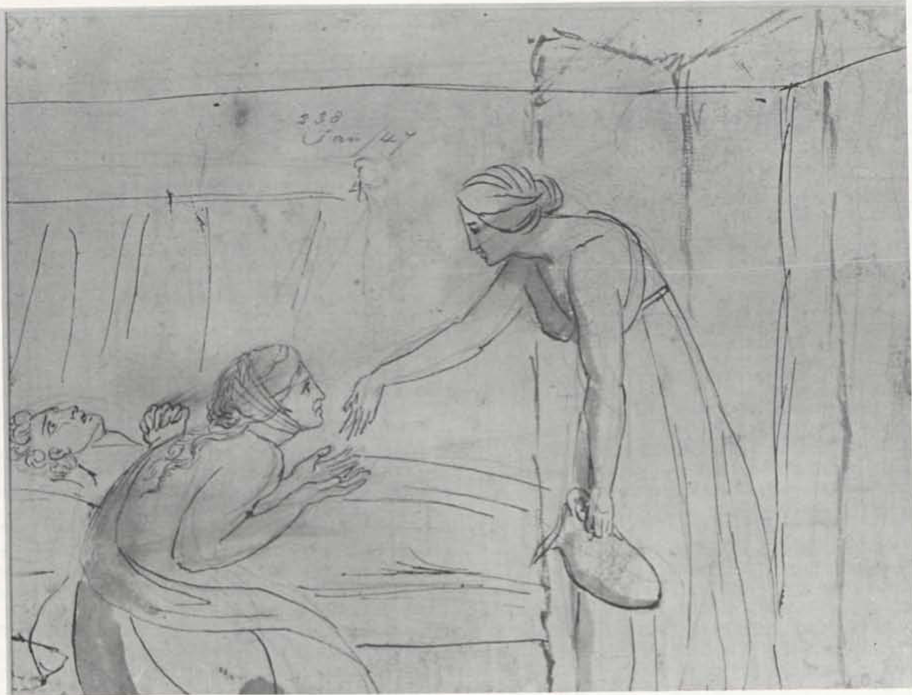

The verso drawing (illus. 9) is clearly a sickbed scene; the drawing is sketchy, but the sick man’s face is strong. The number visible on the drawing identifies it as having once belonged to Joseph Hogarth, a nineteenth-century print seller who acquired his Blakes from Tatham.15↤ 15 See Martin Butlin, “Five Blakes from a Nineteenth-Century Scottish Collection,” Blake Newsletter 25 (Summer 1973), p. 8.

Finally, I shall describe a few items in the collection which in one way or another are associated with William Roscoe, however indirectly. There are in the collection a number of woodblocks attributed to Blake, usually in conjunction with another name. They come from a large collection of blocks, many of which illustrated ballads, chapbooks, and children’s books of the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The blocks attributed to Blake have pencilled notations written on paper labels glued to the blocks; the labels would appear at a guess to be early twentieth century, and are certainly not contemporary with the blocks themselves. The information is puzzlingly specific but, so far, untraceable; for instance, one block is said to belong to Thornton’s Virgil, but it does not illustrate the well-known edition. Several of the others, which clearly form a series, are identified as “Trimmers Bible,” “Mrs. Trimmer,” or “Historical.” The subjects would make it appear very possible that the blocks did illustrate editions of Sarah Trimmer’s various works, but I have so far been unable to find any edition with these illustrations.16↤ 16 It is possible that the attributions are in part simply optimistic reflections of entry No. 132 in A. G. B. Russell, The Engravings of William Blake (London: Grant Richards, 1912), though the information on the labels is quite specific. Photographs of the blocks—made by filling them with talcum powder—have been sent to David Erdman and Robert Essick, who agree that they are not by Blake, and they certainly do not look at all like his work as either designer or engraver.

Perhaps the most interesting of these blocks are two (illus. 10) identified as illustrating a Harris edition of The Butterfly’s Ball, the larger one attributed to “W. Blake & Flaxman” and the other to “W. Blake & Craig.” The attributions seem highly unlikely; the blocks did not illustrate the 1807 or 1808 Harris editions of Roscoe’s poem, nor is there anything in that poem that really fits the scene depicted on the larger of the two blocks. But the information, though in part at least certainly mistaken, is very specific, and the connection with Flaxman seems to make it certain that it was our Blake who was intended. The annotations on other blocks, though sometimes misleading and mistaken, begin page 105 | ↑ back to top

have often proved helpful in tracing those blocks to the works that they originally illustrated. To my eye there is a Blakean quality to the outlined clouds on the larger block, and these two factors make me a little hesitant to reject the attribution outright.The blocks, however, sent me to William Roscoe’s poem, and my impression now is that Roscoe knew Blake’s “A Dream” from Songs of Innocence. The conjunction of emmet, beetle, and glow-worm as watchman seems beyond coincidence. The poem was written about 1802,17↤ 17 The MS of the poem is dated January 1802; see George Chandler, William Roscoe of Liverpool (London: Batsford, 1953), p. 114. but first published in November 1806 in The Gentleman’s Magazine. I quote the most relevant lines from the Harris chapbook edition of 1808: ↤ 18 The lines are quoted from The Butterfly’s Ball and the Grasshopper’s Feast, A Facsimile Reproduction of the Edition of 1808, ed. Charles Welsh (London: Griffith and Farran, 1883); see pp. iii-v, 5, and 7. Some later versions with the same title have a different text. “A Dream” from Songs of Innocence is not one of the poems published by Malkin in 1806, which is in any case too late; see Blake Records, pp. 421-31.

And there came the Beetle, so blind and so black,The last lines quoted are reminiscent of the design as well as mood of the second plate of “The Ecchoing Green.” The poem moralizes just a little at the end, but is infinitely more playful that Watts’ poem about emmets—in the generalizing plural, not the specific singular as in Blake and Roscoe.19↤ 19 See V. de Sola Pinto, “William Blake, Isaac Watts, and Mrs. Barbauld,” in V. de Sola Pinto, ed., The Divine Vision (1957; rpt. New York: Haskell House, 1968), pp. 76-78. The poem was enormously popular, and gave rise to many sequels and imitations. Perhaps, in one way and another, Blake had more effect upon his contemporary world than we usually realize.

Who carried the Emmet, his friend, on his Back.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Then, as Evening gave Way to the Shadows of Night,

Their Watchman, the Glow-worm, came out with a Light.

Then Home let us hasten, while yet we can see,

For no Watchman is waiting for you and for me.

So said little Robert, and pacing along,

His merry Companions returned in a Throng.18

Arnold Goldman has already written an article associating Blake with the Roscoes, suggesting that W. Roscoe may very well have owned a copy of Poetical Sketches which influenced a poem written by his son William Stanley Roscoe.20↤ 20 Arnold Goldman, “Blake and the Roscoes,” N&Q, 210 [N.S. 12] (1965), 178-82. Both subscribed to Cromek’s edition of The Grave, presumably in response to Cromek’s direct solicitation, since he arrived in Liverpool in 1806 armed with a letter of introduction from Fuseli.21↤ 21 See Bentley, Blake Records, p. 179. Roscoe was building a library, and is known to have owned also Hayley’s The Life, and Posthumous Writings of William Cowper, published in 1803 with six plates engraved by Blake.22↤ 22 Goldman, “Blake and the Roscoes,” pp. 179-80. He not only collected books, but wrote an unpublished poem on “The Origin of Engraving,” in addition to quite well-known poems attacking the slave-trade and begin page 106 | ↑ back to top

The collection has one more item related to Roscoe, a copy of Religious Emblems, Being a series of Engravings on Wood, published in 1809 with designs by Thurston and descriptions written by Joseph Thomas, a major patron of Blake. As Leslie Parris has pointed out, the presence of such names as Cromek, Flaxman, and Fuseli in the list of subscribers make it very probable that the “William Blake, Esq.” also listed is our poet.27↤ 27 Leslie Parris, “William Blake’s Mr. Thomas,” TLS, 5 December 1968, p. 1390. See also Blake Records, 165-66. The present copy has been inscribed to Roscoe by the authors, and was doubtless the immediate cause of the fulsome testimonial from Roscoe that Parris records as present in a copy of the work in his possession which had probably belonged to either Thomas or Thurston. The inscription to Roscoe reads thus: “Mr.. Thomas and Mr.. Thurston request Mr.. Roscoes’ acceptance of this work, in testimony, of the high sense they entertain of his distinguished talents and likewise as a mark of their ESTEEM. While [White?] Grove, Epsom Septr.. 1st.. 1809.” The volume also contains a bookplate identifying[e] it as being ex libris William Malin Roscoe, Roscoe’s great-grandson, dated 1897. Roscoe’s library was dispersed by auction after his bankruptcy in 1816, but Roscoe specifically stated that he was withholding from the auction books given him by their authors, and this volume was doubtless among those which thus remained in the family.28↤ 28 Henry Roscoe, Life of William Roscoe, p. 118. The language of the inscription is rather formal, but certainly is one more piece of evidence, however minor, linking Roscoe with Blake’s circle of friends and patrons.

The connections made here between Blake and William Roscoe are all indirect, but I hope that they are suggestive. The work of piecing together a fuller picture of Blake’s relationship with the society of his time is a continuing process, and the kinds of information that can be found in collections such as that at McGill can help to fill in the details of that growing picture.

begin page 107 | ↑ back to top begin page 108 | ↑ back to top